Abstract

The chaperone protein HSPA5/Dna K is conserved throughout evolution from higher eukaryotes down to prokaryotes. The celecoxib derivative OSU-03012 (also called AR-12) interacts with Viagra or Cialis in eukaryotic cells to rapidly reduce HSPA5 levels as well as blunt the functions of many other chaperone proteins. Because multiple chaperones are modulated in eukaryotes, the expression of cell surface virus receptors is reduced and because HSPA5 in blocked viruses cannot efficiently replicate. Because DnaK levels are reduced in prokaryotes by OSU-03012, the levels of DnaK chaperone proteins such as Rec A decline, which is associated with bacterial cell death and a resensitization of so-called drug-resistant superbugs to standard of care antibiotics. In Alzheimer's disease, HSPA5 has been shown to play a supportive role for the progression of tau phosphorylation and neurodegeneration. Thus, in eukaryotes, HSPA5 represents a target for anticancer, antiviral, and anti-Alzheimer's therapeutics and in prokaryotes, DnaK and bacterial phosphodiesterases represent novel antibiotic targets that should be exploited in the future by pharmaceutical companies.

OSU-03012 is a derivative of the drug celecoxib (Celebrex), and lacks cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) inhibitory activity (Kulp et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2004; Johnson et al., 2005). Compared to the parent drug, OSU-03012 has a greater level of bioavailability in preclinical large animal models when compared to the parent compound and, in our hands, has an order of magnitude greater efficacy at killing tumor cells (Yacoub et al., 2006; Park et al., 2008; Booth et al., 2012a). Based on encouraging preclinical data, OSU-03012 underwent phase I evaluation in cancer patients; several patients were on this trial with stable disease for up to 9 months without any DLTs. Due to a lack of sufficient funds at the licensee of OSU-03012 and a reduction in its stock market value, Arno Therapeutics (ARNI:OTC US), the further development of this agent in the treatment of cancer has presently stalled.

Initially, the tumoricidal effects of OSU-03012 in transformed cells were argued to be through direct inhibition of the enzyme PDK-1, within the PI3K pathway (Zhu et al., 2004). However, our data have strongly argued that the OSU-03012 toxicity could not simplistically be attributed to the suppression of PDK-1 signaling (Park et al., 2008; Booth et al., 2012a, 2012b). Our prior studies demonstrated that OSU-03012 killed tumor cells through mechanisms that involved enhanced endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress signaling through activation of PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), and downregulation/reduced half-life of the ER, and plasma membrane localized HSP70 family chaperone GRP78/BiP/HSPA5 (Yacoub et al., 2006; Park et al., 2008; Booth et al., 2012a, 2012b). One of the hallmarks of any potentially useful anticancer drug is that it is found to be relatively nontoxic to normal cells/tissues, and we have shown on multiple occasions that OSU-03012, alone or in combination with other cancer modalities, had an excellent therapeutic window comparing toxicity in normal nontransformed cells to tumor cells both in vitro and in vivo.

HSPA5 plays a key role in regulating the ER stress response; under resting conditions, the majority of HSPA5 is associated with PERK and keeps the protein in an inactive state (Rao et al., 2012; Gorbatyuk and Gorbatyuk, 2013; Roller and Maddalo, 2013). HSPA5, as a chaperone, also plays an important role in the protein folding processes that occur in the ER, including during cancer, liver disease, and virus replication. The prokaryotic homologue of HSPA5, DnaK, also plays an essential role in bacterial cell biology where it chaperones proteins such as Rec A, which is essential for bacterial DNA replication and survivability when engulfed and subjected to the respiratory burst of macrophages (Roux, 1990; Earl et al., 1991; Anderson et al., 1992; Hogue and Nayak, 1992; Carleton and Brown, 1997; Xu et al., 1997; Xu et al., 1998; Mirazimi and Svensson, 2000; Bolt, 2001; Bredèche et al., 2001; Shen et al., 2002; Dimcheff et al., 2004; He, 2006; Spurgers et al., 2010; Goodwin et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2011; Dabo and Meurs, 2012; Burugu et al., 2014; Moreno and Tiffany-Castiglioni, 2014; Reid et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014). When high levels of unfolded protein are present in the ER, for example, in a tumor cell or in a virally infected cell or in a rapidly dividing bacterial cell, HSPA5 disassociates from PERK resulting in its activation, and HSPA5 binds to the unfolded proteins in the ER as a chaperone to promote refolding into the active conformation (Lee, 2007; Ni and Lee, 2007; Luo and Lee, 2013; Chen et al., 2014; Lee, 2014 and references in both reviews). Activation of PERK-eIF2α signaling acts to prevent the majority of cellular proteins from being synthesized, although can enhance further HSPA5 production. As HSPA5 chaperones the unfolded protein(s) into the correct conformation and dissociates afterward, free HSPA5 eventually becomes available to reassociate with PERK, thereby shutting off the ER stress signaling system (Hollien and Weissman, 2006; Lee, 2007; Pavitt and Ron, 2012; Luo and Lee, 2013; Sano and Reed, 2013; Chen et al., 2014; Lee, 2014; Zhu and Lee, 2014).

Based on an unbiased search of the National Library of Medicine database, it is self-evident that HSPA5 and evolutionary conserved homologues of HSPA5 play essential roles in the biology and life cycles of viruses, bacteria, protosoal, and yeast cells, as well as higher eukaryotic cells, in particular, tumor cells that express high levels of many activated oncogenic signaling proteins. The expression of HSPA5 is essential for the replication and productive virus release for many well-known pathogenic viruses such as Ebola, Cytomegalovirus, Chikungunya, Measles, HIV, Influenza, Lassa, and Marburg. Some viruses such as the dengue fever virus are reported to actually infect cells through a cell surface expressed HSPA5 protein (Quinones et al., 2008). Even the receptor tyrosine kinase ERBB1 has been argued to be an essential signaling cofactor for RSV infection. HSPA5 also plays an essential role in the viability of unicellular parasites such as leishmania, malaria, and yeasts (Jensen et al., 2001; Cortes et al., 2003; Kimata and Kohno, 2011). Even in prokaryotes, three proteins, DnaK (HSPA5), DnaJ (HSP40), and GrpE (HSP27), are very similar and complex as functional homologues of mammalian proteins and play an essential role in bacterial growth and viability, for example, by regulating RecA expression (Noguchi et al., 2014). Phosphodiesterase enzymes, the clinical targets of multiple FDA-approved PDE5 and PDE3 inhibitors in humans, are also expressed in bacteria, unicellular organisms, and throughout evolution in mammals (Schmidt et al., 2005; Tuckerman et al., 2011; Kwan et al., 2014).

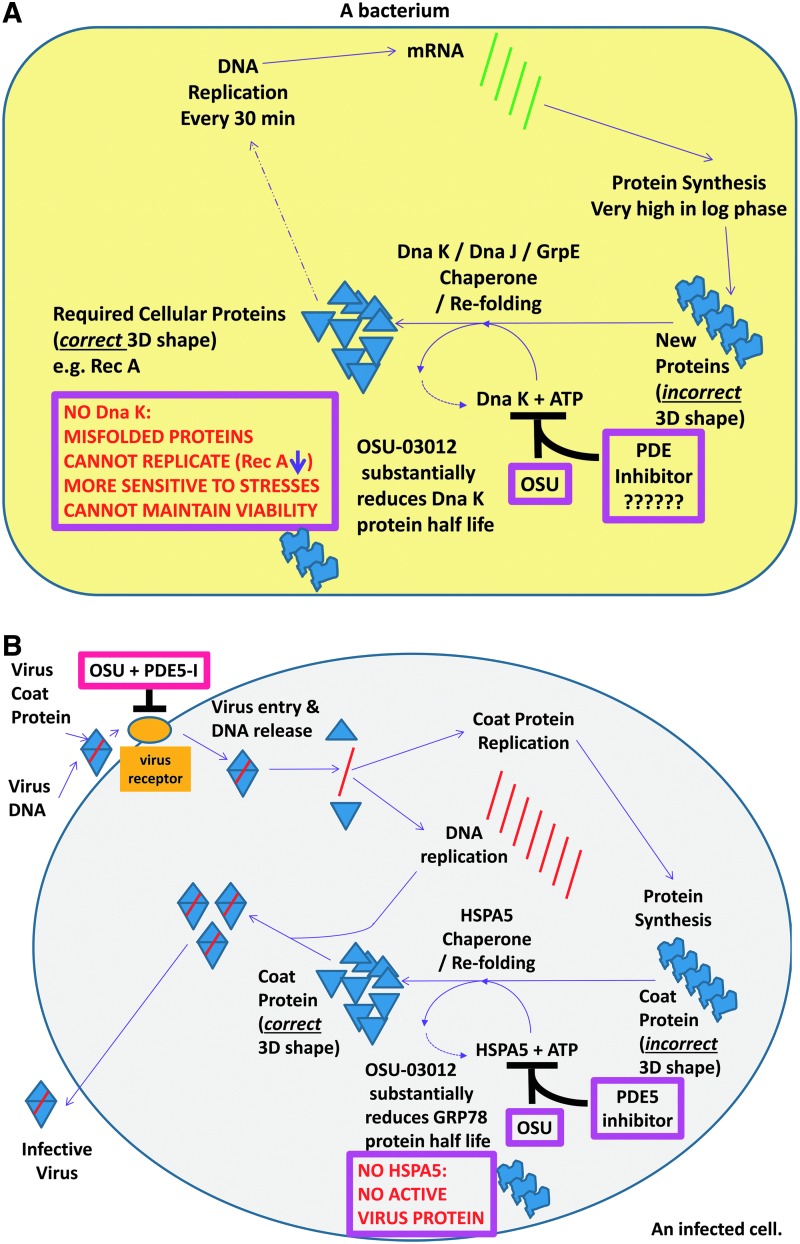

In the recently published studies by Booth et al. examining the role of HSPA5 in the biology of tumor cells, bacterial cells, and virus replication, the bacterial HSPA5 homologue, DnaK, was downregulated by OSU-03012 that correlated with reduced expression of chaperoned proteins, for example, Rec A, and rendered bacteria more sensitive to antibacterial drugs and in some cases, the phosphodiesterase inhibitor tadalafil (Roberts et al., 2014; Booth et al., 2015). More particularly, in antibiotic-resistant superbug forms of Neisseria gonorrhoeae OSU-03012 also resensitized these bacteria to multiple standard of care antibiotics. Loss of Rec A also sensitizes N. gonorrhoeae to the respiratory burst and OSU-03012 by stimulating autophagy more rapidly and digests and kills Salmonella typhimurium and other bacteria (Chiu et al., 2009a, 2009b; Ostberg et al., 2013). Thus, DnaK and potentially other bacterial chaperones represent a new set of targets for antibiotic development. Furthermore, our data with sildenafil (Viagra) and tadalafil (Cialis) demonstrate that bacterial phosphodiesterases may also represent a new target for future antibiotic development (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Possible molecular mechanisms by which OSU-03012 and PDE inhibitors could (A) prevent bacterial growth and (B) prevent infection and production of new infective virions. The ability of OSU-03012 alone, or enhanced by a PDE5 inhibitor, to reduce HSPA5 expression and the function of multiple other chaperones will prevent the correct folding of essential tumor cell/virus/bacterial proteins resulting in dead tumor cells/inactive virus materials/dead bacteria. The combination of OSU-03012 and a PDE5 inhibitor will also reduce the expression of plasma membrane receptors whose expression is essential for bacterial and viral infection. Thus, treatment of cells with OSU-03012 and a PDE5 inhibitor will both reduce bacterial/virus infection and virus production/bacterial growth simultaneously. Collectively our data strongly argue that it is a strong possibility that our drug combination will have profound antiviral/antibacterial capabilities. ?????? represents a choice of PDE5 inhibitors; Viagra, Cialis, Levitra.

Low levels of HSPA5 expression are essential for regulating the ER stress response of normal nontransformed cells and for the folding of the relatively low levels of protein production in nontransformed cells. In tumor cells, regardless of their proliferative state, with very high basal protein expression levels or in the reproduction cycle of viruses in higher eukaryotes, the HSPA5 protein, together with other chaperone proteins, including HSP27, HSP40, HSP60, HSP90, GRP94, and HSP70, is essential for the ATP-dependent correct folding of highly expressed host and viral proteins, including the virus capsid proteins. Because viruses synthesize large amounts of protein, they induce a rapid intense ER stress response in infected cells, including stimulation of additional HSPA5 expression that is essential for the correct viral protein folding and the overall transient cell survival maintenance purposes of the virus. Some viral proteins are known to suppress the intense PERK-eIF2α signaling response to viral protein production through increasing association of the protein ser/thr phosphatase PP1 with eIF2α, to ensure that just the right amount of ER stress is signaled in a virus-infected cell. Thus, a virus-infected cell with a high protein load becomes only capable of signaling a diminuted stress response, that is, promoting a survival ER stress response rather than a ER stress death response that would usually be generated by such an intense unfolded protein response (Rathore et al., 2013). Hence, based on our findings we would argue that OSU-03012 disrupts the Goldilocks virus modulation of ER stress to prevent virus replication.

OSU-03012, unlike the parent compound celecoxib, actually destabilizes the HSPA5 protein causing its protein half-life to be profoundly reduced without modulating the HSPA5 promoter, and OSU-03012 when combined with sildenafil/tadalafil rapidly further reduces the decline in total HSPA5 levels by >>90% in all the cell lines tested (Booth et al., 2012a, 2014a, 2014b, 2014c, 2014d, 2015a, 2015b). The ability of a PDE5 inhibitor to facilitate the breakdown of HSPA5 is predominantly reliant on cGMP/PKG signaling, with inhibition of nitric oxide synthase enzymes having a much more modest effect. Treatment of adenovirus/ coxsackie virus-infected cells with OSU-03012 and sildenafil decreased the release of active virus particles as judged by decreased cell lysis/cell death caused by virus reproduction. Furthermore, OSU-03012 and sildenafil treatment reduced expression of multiple membrane virus receptors essential for host infection by adenovirus/ coxsackie virus, as well as by Ebola, Marburg, Chikungunya, Lassa fever, Hepatitis A, Hepatitis B, and Hepatitis C viruses. The majority of virus receptors were dependent for chaperones other than HSPA5 for their expression/stability. A vast number of human viruses rely on HSPA5 expression and those of other chaperones for their life cycle, for example, Ebola and Influenza, and for the further induction of HSPA5 to facilitate production of functional native conformation viral proteins and, obviously, new virus particles. Hence, collectively our data argue that the combination of OSU-03012 and PDE5 inhibitors could potentially be developed into a potent antiviral therapy for viral diseases ranging from Ebola to Influenza to the common cold by reducing the level of infectivity and reducing functional virion production (Fig. 1B).

Treatment of cells with OSU+SIL rapidly reduces the expression of HSPA5 in vitro, and as we have now observed in mice, in vivo in the liver and brains of animals, as well as reducing the functions of multiple other cell survival chaperones and plasma membrane drug efflux pumps responsible for drug resistance in cancer cells and the blood/brain barrier (Booth et al., 2015b). Although not experimentally explored in the article by Booth et al. (2015), enhanced HSPA5 chaperone function, and those of other chaperones, has been strongly implicated in the biology of other debilitating human diseases, for example, most notably Alzheimer's disease. Without HSPA5 or the activities of other chaperones, less overall protein will be expressed in neurons and less tau hyperphosphorylation will occur. Thus, the initial onset and progression of the disease will be blunted by OSU-03012 and especially by OSU-03012 and Viagra therapy. However, in neurons already heavily loaded with beta-amyloid protein as in transgenic animal models, HSPA5 overexpression has been shown to maintain neurological function by preventing the formation of insoluble beta-amyloid aggregates. Thus, the use of OSU-03012±Viagra in the earliest stages of this disease, but not in patients already debilitated by the disease, may be of considerable therapeutic use. As brain-permeant PDE5 inhibitors are also considered to be potentially useful agents in Alzheimer's disease treatment and as OSU-03012 also rapidly crosses the blood/brain barrier, the possibilities of also developing an effective OSU+PDE5 inhibitor therapy regimen for this debilitating disease together with those previously mentioned in this article could have profound health implications in many areas of human health (Black et al., 2008; García-Barroso et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Devan et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2014).

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Anderson K., Stott E.J., and Wertz G.W. (1992). Intracellular processing of the human respiratory syncytial virus fusion glycoprotein: amino acid substitutions affecting folding, transport and cleavage. J Gen Virol 73,1177–1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black K.L., Yin D., Ong J.M., Hu J., Konda B.M., Wang X., Ko M.K., Bayan J.A., Sacapano M.R., Espinoza A., Irvin D.K., and Shu Y. (2008). PDE5 inhibitors enhance tumor permeability and efficacy of chemotherapy in a rat brain tumor model. Brain Res 1230,290–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolt G. (2001). The measles virus (MV) glycoproteins interact with cellular chaperones in the endoplasmic reticulum and MV infection upregulates chaperone expression. Arch Virol 146,2055–2068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth L., Cazanave S.C., Hamed H.A., Yacoub A., Ogretmen B., Chen C.S., Grant S., and Dent P. (2012a). OSU-03012 suppresses GRP78/BiP expression that causes PERK-dependent increases in tumor cell killing. Cancer Biol Ther 13,224–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth L., Cruickshanks N., Ridder T., Chen C.S., Grant S., and Dent P. (2012b). OSU-03012 interacts with lapatinib to kill brain cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther 13,1501–1511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth L., Roberts J.L., Cash D.R., Tavallai S., Jean S., Fidanza A., Cruz-Luna T., Siembiba P., Cycon K.A., Cornelissen C.N., and Dent P. (2015a). GRP78/BiP/HSPA5/Dna K is a universal therapeutic target for human disease. J Cell Physiol [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1002/jcp.24919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth L., Roberts J.L., Conley A., Cruickshanks N., Ridder T., Grant S., Poklepovic A., and Dent P. (2014a). HDAC inhibitors enhance the lethality of low dose salinomycin in parental and stem-like GBM cells. Cancer Biol Ther 15,305–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth L., Roberts J.L., Cruickshanks N., Conley A., Durrant D.E., Das A., Fisher P.B., Kukreja R.C., Grant S., Poklepovic A., and Dent P. (2014b). Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors enhance chemotherapy killing in gastrointestinal/genitourinary cancer cells. Mol Pharmacol 85,408–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth L., Roberts J.L., Cruickshanks N., Grant S., Poklepovic A., and Dent P. (2014c). Regulation of OSU-03012 toxicity by ER stress proteins and ER stress-inducing drugs. Mol Cancer Ther 13,2384–2398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth L., Roberts J.L., Cruickshanks N., Tavallai S., Webb T., Samuel P., Conley A., Binion B., Young H.F., Poklepovic A., Spiegel S., and Dent P. (2014d). PDE5 inhibitors enhance Celecoxib killing in multiple tumor types. J Cell Physiol [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1002/jcp.24843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredèche M.F., Ehrlich S.D., and Michel B. (2001). Viability of rep recA mutants depends on their capacity to cope with spontaneous oxidative damage and on the DnaK chaperone protein. J Bacteriol 183,2165–2171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burugu S., Daher A., Meurs E.F., and Gatignol A. (2014). HIV-1 translation and its regulation by cellular factors PKR and PACT. Virus Res 193,65–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton M., and Brown D.T. (1997). The formation of intramolecular disulfide bridges is required for induction of the Sindbis virus mutant ts23 phenotype. J Virol 71,7696–7703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.T., Zhu G., Pfaffenbach K., Kanel G., Stiles B., and Lee A.S. (2014). GRP78 as a regulator of liver steatosis and cancer progression mediated by loss of the tumor suppressor PTEN. Oncogene 33,4997–5005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu H.C., Kulp S.K., Soni S., Wang D., Gunn J.S., Schlesinger L.S., and Chen C.S. (2009a). Eradication of intracellular Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium with a small-molecule, host cell-directed agent. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53,5236–5244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu H.C., Soni S., Kulp S.K., Curry H., Wang D., Gunn J.S., Schlesinger L.S., and Chen C.S. (2009b). Eradication of intracellular Francisella tularensis in THP-1 human macrophages with a novel autophagy inducing agent. J Biomed Sci 16,110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes G.T., Winograd E., and Wiser M.F. (2003). Characterization of proteins localized to a subcellular compartment associated with an alternate secretory pathway of the malaria parasite. Mol Biochem Parasitol 129,127–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabo S., and Meurs E.F. (2012). dsRNA-dependent protein kinase PKR and its role in stress, signaling and HCV infection. Viruses 4,2598–2635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devan B.D., Pistell P.J., Duffy K.B., Kelley-Bell B., Spangler E.L., and Ingram D.K. (2014). Phosphodiesterase inhibition facilitates cognitive restoration in rodent models of age-related memory decline. NeuroRehabilitation 34,101–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimcheff D.E., Faasse M.A., McAtee F.J., and Portis J.L. (2004). Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress induced by a neurovirulent mouse retrovirus is associated with prolonged BiP binding and retention of a viral protein in the ER. J Biol Chem 279,33782–33790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earl P.L., Moss B., and Doms R.W. (1991). Folding, interaction with GRP78-BiP, assembly, and transport of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope protein. J Virol 65,2047–2055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Barroso C., Ricobaraza A., Pascual-Lucas M., Unceta N., Rico A.J., Goicolea M.A., Sallés J., Lanciego J.L., Oyarzabal J., Franco R., Cuadrado-Tejedor M., and García-Osta A. (2013). Tadalafil crosses the blood-brain barrier and reverses cognitive dysfunction in a mouse model of AD. Neuropharmacology 64,114–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin E.C., Lipovsky A., Inoue T., Magaldi T.G., Edwards A.P., Van Goor K.E., Paton A.W., Paton J.C., Atwood W.J., Tsai B., and DiMaio D. (2011). BiP and multiple DNAJ molecular chaperones in the endoplasmic reticulum are required for efficient simian virus 40 infection. MBio 2,e00101–e00111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbatyuk M.S., and Gorbatyuk O.S. (2013). The molecular chaperone GRP78/BiP as a therapeutic target for neurodegenerative disorders: a mini review. J Genet Syndr Gene Ther 4, pii: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He B. (2006). Viruses, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and interferon responses. Cell Death Differ 13,393–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue B.G., and Nayak D.P. (1992). Synthesis and processing of the influenza virus neuraminidase, a type II transmembrane glycoprotein. Virology 188,510–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollien J., and Weissman J.S. (2006). Decay of endoplasmic reticulum-localized mRNAs during the unfolded protein response. Science 313,104–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen A.T., Curtis J., Montgomery J., Handman E., and Theander T.G. (2001). Molecular and immunological characterisation of the glucose regulated protein 78 of Leishmania donovani. Biochim Biophys Acta 1549,73–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A.J., Smith L.L., Zhu J., Heerema N.A., Jefferson S., Mone A., et al. (2005). A novel celecoxib derivative, OSU-03012, induces cytotoxicity in primary CLL cells and transformed B-cell lymphoma cell line via a caspase-and Bcl-2-independent mechanism. Blood 105,2504–2509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimata Y., and Kohno K. (2011). Endoplasmic reticulum stress-sensing mechanisms in yeast and mammalian cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol 23,135–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulp S.K., Yang Y.T., Hung C.C., Chen K.F., Lai J.P., Tseng P.H., Fowble J.W., Ward P.J., and and Chen C.S. (2004). 3-Phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1/Akt signaling represents a major cyclooxygenase-2-independent target for celecoxib in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res 64,1444–1451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan B.W., Osbourne D.O., Hu Y., Benedik M.J., and Wood T.K. (2014). Phosphodiesterase DosP increases persistence by reducing cAMP which reduces the signal indole. Biotechnol Bioeng [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1002/bit.25456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A.S. (2007). GRP78 induction in cancer: therapeutic and prognostic implications. Cancer Res 67,3496–3499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A.S. (2014). Glucose-regulated proteins in cancer: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Cancer 14,263–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo B., and Lee A.S. (2013). The critical roles of endoplasmic reticulum chaperones and unfolded protein response in tumorigenesis and anticancer therapies. Oncogene 32,805–818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirazimi A., and Svensson L. (2000). ATP is required for correct folding and disulfide bond formation of rotavirus VP7. J Virol 74,8048–8052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno J.A., and Tiffany-Castiglioni E. (2014). The chaperone Grp78 in protein folding disorders of the nervous system. Neurochem Res [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1007/s11064-014-1405-0; PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni M., and Lee A.S. (2007). ER chaperones in mammalian development and human diseases. FEBS Lett 581,3641–3651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi A., Ikeda A., Mezaki M., Fukumori Y., and Kanemori M. (2014). DnaJ-promoted binding of DnaK to multiple sites on σ32 in the presence of ATP. J Bacteriol 196,1694–1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostberg K.L., DeRocco A.J., Mistry S.D., Dickinson M.K., and Cornelissen C.N. (2013). Conserved regions of gonococcal TbpB are critical for surface exposure and transferrin iron utilization. Infect Immun 81,3442–3450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M.A., Yacoub A., Rahmani M., Zhang G., Hart L., Hagan M.P., et al. (2008). OSU-03012 stimulates PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum-dependent increases in 70-kDa heat shock protein expression, attenuating its lethal actions in transformed cells. Mol Pharmacol 73,1168–1184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavitt G.D., and Ron D. (2012). New insights into translational regulation in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4, pii: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinones Q.J., de Ridder G.G., and Pizzo S.V. (2008). GRP78: a chaperone with diverse roles beyond the endoplasmic reticulum. Histol Histopathol 23,1409–1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao R., Fiskus W., Ganguly S., Kambhampati S., and Bhalla K.N. (2012). HDAC inhibitors and chaperone function. Adv Cancer Res 116,239–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathore A.P.S., Ng M.L., and Vasudevan S.G. (2013). Differential unfolded protein response during Chikungunya and Sindbis virus infection: CHIKV nsP4 suppresses eIF2α phosphorylation. Virol J 10,36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid S.P., Shurtleff A.C., Costantino J.A., Tritsch S.R., Retterer C., Spurgers K.B., and Bavari S. (2014). HSPA5 is an essential host factor for Ebola virus infection. Antiviral Res 109,171–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts J.L., Booth L., Conley A., Cruickshanks N., Malkin M., Kukreja R.C., Grant S., Poklepovic A., and Dent P. (2014). PDE5 inhibitors enhance the lethality of standard of care chemotherapy in pediatric CNS tumor cells. Cancer Biol Ther 15,758–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roller C., and Maddalo D. (2013). The molecular chaperone GRP78/BiP in the development of chemoresistance: mechanism and possible treatment. Front Pharmacol 4,10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux L. (1990). Selective and transient association of Sendai virus HN glycoprotein with BiP. Virology 175,161–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano R., and Reed J.C. (2013). ER stress-induced cell death mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta 1833,3460–3470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A.J., Ryjenkov D.A., and Gomelsky M. (2005). The ubiquitous protein domain EAL is a cyclic diguanylate-specific phosphodiesterase: enzymatically active and inactive EAL domains. J Bacteriol 187,4774–4781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Meunier L., and Hendershot L.M. (2002). Identification and characterization of a novel endoplasmic reticulum (ER) DnaJ homologue, which stimulates ATPase activity of BiP in vitro and is induced by ER stress. J Biol Chem 277,15947–15956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spurgers K.B., Alefantis T., Peyser B.D., Ruthel G.T., Bergeron A.A., Costantino J.A., Enterlein S., Kota K.P., Boltz R.C., Aman M.J., Delvecchio V.G., and Bavari S. (2010). Identification of essential filovirion-associated host factors by serial proteomic analysis and RNAi screen. Mol Cell Proteomics 9,2690–2703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuckerman J.R., Gonzalez G., and Gilles-Gonzalez M.A. (2011). Cyclic di-GMP activation of polynucleotide phosphorylase signal-dependent RNA processing. J Mol Biol 407,633–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu A., Bellamy A.R., and Taylor J.A. (1998). BiP (GRP78) and endoplasmin (GRP94) are induced following rotavirus infection and bind transiently to an endoplasmic reticulum-localized virion component. J Virol 72,9865–9872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Jensen G., and Yen T.S. (1997). Activation of hepatitis B virus S promoter by the viral large surface protein via induction of stress in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Virol 71,7387–7392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yacoub A., Park M.A., Hanna D., Hong Y., Mitchell C., Pandya A.P., et al. (2006). OSU-03012 promotes caspase-independent but PERK-, cathepsin B-, BID-, and AIF-dependent killing of transformed cells. Mol Pharmacol 70,589–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Chen S., Zhang J., Li C., Sun Y., Zhang L., and Zheng X. (2014). Stimulation of autophagy prevents amyloid-β peptide-induced neuritic degeneration in PC12 cells. J Alzheimers Dis 40,929–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Li S., Yang C., Wei M., Song C., Zheng Z., Gu Y., Du H., Zhang J., and Xia N. (2011). Homology model and potential virus-capsid binding site of a putative HEV receptor Grp78. J Mol Model 17,987–995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Guo J., Zhao X., Chen Z., Wang G., Liu A., Wang Q., Zhou W., Xu Y., and Wang C. (2013). Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor sildenafil prevents neuroinflammation, lowers beta-amyloid levels and improves cognitive performance in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Behav Brain Res 250,230–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Sun Y., Chen H., Dai Y., Zhan Y., Yu S., Qiu X., Tan L., Song C., and Ding C. (2014). Activation of the PKR/eIF2α signaling cascade inhibits replication of Newcastle disease virus. Virol J 11,62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu G., and Lee A.S. (2014). Role of the unfolded protein response, GRP78 and GRP94 in organ homeostasis. J Cell Physiol [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1002/jcp.24923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Huang J.W., Tseng P.H., Yang Y.T., Fowble J.W., Shiau C.W., et al. (2004). From the cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib to a novel class of 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 inhibitors. Cancer Res 64,4309–4318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]