Abstract

In gene therapy trials targeting blood disorders, it is important to detect dominance of transduced hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) clones arising from vector insertion site (VIS) effects. Current methods for VIS analysis often do not have defined levels of quantitative accuracy and therefore can fail to detect early clonal dominance. We have developed a rapid and inexpensive method for measuring clone size based on random shearing of genomic DNA, minimal exponential PCR amplification, and shear site counts as a quantitative endpoint. This quantitative shearing linear amplification PCR (qsLAM PCR) assay utilizes an internal control sample containing 19 lentiviral insertion sites per cell that is mixed with polyclonal samples derived from transduced human CD34+ cells. Samples were analyzed from transplanted pigtail macaques and from a participant in our X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (XSCID) lentiviral vector trial and yielded controlled and quantitative results in all cases. One case of early clonal dominance was detected in a monkey transplanted with limiting numbers of transduced HSCs, while the clinical samples from the XSCID trial participant showed highly diverse clonal representation. These studies demonstrate that qsLAM PCR is a facile and quantitative assay for measuring clonal repertoires in subjects enrolled in human gene therapy trials using lentiviral-transduced HSCs.

Introduction

Genomic integration of retroviral vectors has led to hematopoietic malignancies in several clinical gene therapy trials for immunodeficiency syndromes because of inadvertent activation of cellular proto-oncogenes by retroviral enhancer elements.1–3 The development of these leukemias was typically preceded by dominance of an individual hematopoietic clone because of alterations in cell growth induced by the vector integration event.4–7 In these immunodeficiency trials, the emergence of clonal dominance was demonstrated retrospectively using banked samples, obtained prior to the emergence of clinical leukemia, that were subsequently analyzed by real-time PCR (qPCR) using primers specific for the oncogenic vector integration site (VIS). More recently, a case of prospective identification of a dominant clone has been described in a gene therapy trial for β-thalassemia using a deep-sequencing VIS analysis.8 The dominant clone has been reported to be stable in size and may reflect oligoclonal repopulation arising from transplant of limited numbers of transduced hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) rather than growth perturbation per se. Deep-sequencing-based VIS assays may also be useful for studying the biology of transplanted hematopoietic systems9; however, these studies are best accomplished using barcoded sequence libraries embedded within the vector genome10–12—an approach not likely adaptable for use in clinical trials. Therefore, there is a need for better VIS assays for prospective monitoring of emerging clonal dominance in human stem cell gene therapy trials and for studying the biology of the reconstituted hematopoietic systems at a clonal level.

A variety of VIS assays based on deep sequencing have been developed for monitoring clonality in human gene therapy subjects and are typically based on PCR methodologies to amplify vector–genome junctions.13–15 When these assays are based on early stage restriction enzyme digestion, such as in the linear amplification mediated PCR (LAM PCR) assay,16 they can give nonquantitative results based on variability in the location of the genomic restriction enzyme site and resultant differences in PCR amplification efficiency.13,17–19 Newer methods that eliminate the requirement for restriction enzyme digestion can circumvent this particular limitation,20–25 but are often accompanied by reduced overall sensitivity and lack of rigorous quantitative controls. Without controls containing a multiplex of known integration sites at defined frequencies, it can be difficult to assess data arising from complex samples for the failure to detect clones that are present (false negatives) and/or the presence of amplicons not based on true integration events within the genome (false positives).17 In our experience, this is more common than generally realized. In addition, many current methods are reliant upon pyrosequencing, relatively expensive, and not generally available to gene therapy investigators outside of collaboration with centers of expertise.

Here we describe a relatively expedient and quantitatively defined method for measuring hematopoietic clone size based on generating vector–genome fragments by random shearing. This method, known as quantitative shearing linear amplification PCR (qsLAM PCR), is based on minimizing the number of exponential PCR cycles, inclusion of an internal control sample with known frequencies of diverse insertion sites, deep sequencing using the Illumina MiSeq system, and use of a bioinformatic endpoint based on counting the number of unique shear sites for a given integration rather than the more traditional read count analysis. We demonstrate how qsLAM PCR can be used to measure clone sizes in highly polyclonal samples derived from transplanted pigtail macaques and a gene therapy subject enrolled on our LVXSCID-OC gene therapy trial.

Materials and Methods

The qsLAM PCR assay

One microgram of genomic DNA was sonicated with the Covaris E210 instrument at 200 cycles per burst, 5% duty cycle, 3 intensity, 6 water level, and 65 sec. The sheared DNA was then subject to end repair using the NEB end repair module followed by dA tailing using the NEB dA tailing module. The dA tailed DNA was ligated with the NEBNext Adaptor for Illumina using the NEB T4 ligation kit, followed by treatment with the USER enzyme. The resulting product was then used as template for linear PCR using a biotinylated primer (P1; biotin AGTAGTGTGTGCCCGTCTGT),15 which binds to the CL20 lentiviral vector LTR. Linear amplification was performed using the 2xPCR Master Mix (Qiagen) at the following conditions: 95°C for 6 min, and 95°C for 30 sec, 58°C for 5 min, and 72°C for 1 min, totally 50 cycles, followed by a further 7 min incubation at 72°C. The linear PCR product was purified using the streptavidin-conjugated magnetic beads Dynal M-270 (Life Technologies). The purified linear PCR product was then used as template for another 12 cycles of PCR using nested PCR primers that are tagged with sequences necessary for Illumina sequencing on the MiSeq instrument.

The PCR was performed using the NEBNext High-Fidelity 2xPCR Master Mix at the following conditions: 98°C for 30 sec, and 98°C for 10 sec, 55°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec, for 12 cycles, followed by a further 5 min incubation at 72°C. The LTR primer used for the nested PCR was AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTNNNACTGGGATCCCTCAGACCCTTTTAGTC (N represents any of the four nucleotides). The other primer for the nested PCR binds to the adaptor (13 bp complementary) and is provided in the NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina kit. The final PCR product was size-selected for the 250–800 bp fragments on a 2% E-gel (Life Technologies), was purified, and sequenced on a MiSeq instrument (Illumina). An amount of 50–250 ng DNA from each sample (5–25% of the original 1 μg volume equivalent) was multiplexed and sequenced in each run. All purification steps were performed with either the MinElute PCR purification kit (Qiagen) or the PCR purification kit (Qiagen). For each DNA sample, only one shearing and one single qsLAM PCR run was performed. Further details of the key reagents are listed in Supplementary Table S1 (Supplementary Material is available online at www.liebertpub.com/hgtb).

Generation of Jurkat clone with defined VIS

Jurkat cells were transduced with the CL20-4i-EF1a-hγcOPT vector26 at an MOI of 100 and were subsequently sorted into 96-well plates at 1 cell/well. Cell clones were expanded and genomic DNA was extracted from selected clones. Vector copy number (VCN) was measured using quantitative PCR method.26 One clone with an estimated VCN of 19 was chosen for further experiments. VCN was verified by Southern blot analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridization using a vector-specific probe. The purified plasmid containing 4458 bp of the provirus form of the integrated vector was labeled with a red-dUTP (AF594; Molecular Probes) by nick translation. The labeled probe was combined with sheared human DNA and hybridized to metaphase chromosomes or interphase chromatin derived from the 19 copy Jurkat cell clone using routine cytogenetic harvest methods in a solution containing 50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, and 2× SSC. The slide was then washed, stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and analyzed.

Transduction of CD34+ cells

G-CSF mobilized human peripheral blood CD34+ cells were transduced with the CL20-4i-EF1a-hγcOPT vector that was either transiently prepared in transfected 293T cells (CD34A) or produced from a lentiviral vector producer clone (CD34B)27 at an MOI of 50 in XVivo-10 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum and 100 ng/ml each of the recombinant human cytokines stem cell factor, thrombopoietin, and ligand for FLT3. The cells were cultured for 5 days and genomic DNA was extracted for further analysis using the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen). The details for transduction of the G-CSF-mobilized bone marrow CD34+ cells from pig-tailed macaque with lentiviral vectors will be described in another article (Bonner M et al., in preparation).

Patient sample collection

The study subject was 24 years old, had waning immune function despite prior treatment with an allogeneic transplant for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (XSCID), and was subsequently enrolled in the LVXSCID-OC clinical trial (NIAID IRB-approved protocol 11-I-0007) at the National Institute of Health Clinical Center after appropriate informed consent (Drs. DeRavin and Malech, PI). Mobilized CD34+ peripheral blood cells were transduced with the CL20-4i-EF1a-hγcOPT vector and reinfused after subablative conditioning therapy with busulfan. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were collected at 3 months after infusion of genetically modified cells. Red blood cells were lysed and the nucleated cells were stained with CD14+ antibody (clone M5E2) and CD16+ antibody (clone 3G8) and sorted for CD14+ and CD16+ cell populations. Genomic DNA was extracted from the sorted cells using the DNeasy Tissue and Blood kit (Qiagen).

Bioinformatic analysis

After the adapter sequences were removed from analysis, the paired-end reads were trimmed against low base quality scores and ambiguous nucleotides. Only the high-quality paired-end reads with the LTR sequences (20 bp, positions from −24 to −5) containing at least 30 nucleotides of human or rhesus macaque genomic DNA sequence were uniquely mapped to a human reference genome (UCSC assembly hg19, GRCh37, February 2009) or a rhesus reference genome (BGI CR_1.0/rheMac3) using CLC Genomics Workbench v6.5 (CLC Bio, Denmark). The viral integration sites and their directions were established on mapped reads with LTR orientations. The integration sites were further defined as clusters within a 7 bp window centered at sites with the highest read coverage, and the total number of reads of each cluster was counted for the overall coverage. In addition, the number of distinct reads within the cluster, after removing the PCR duplicates (identical start–stop mapping positions), was counted (shear sites) for unique coverage for each integration site. A 1 bp difference is counted as a new shear site.

Results

The qsLAM PCR strategy

The first step for most VIS analyses typically involves addition of an adaptor to fragment ends close to the VIS. Digestion of DNA with restriction endonuclease followed by adaptor ligation can result in addition of adaptors that are too close to or too distant from the VIS, precluding efficient PCR amplification and accurate quantitation of VIS frequencies. To circumvent this limitation, qsLAM PCR is based on random sonication so that the average DNA fragment size can be controlled to average about 250–800 bp per sonicated sample. While some shearing sites can still be too close to the VIS, the random shearing does allow fragments with appropriate length to be generated for a given clone. Another advantage of random shearing is that each individual shear site arising from a specific VIS will be unique (Fig. 1A), allowing the clonal abundance to be estimated by counting the number of unique shear sites associated with each VIS.20,24,28

FIG. 1.

Strategy for qsLAM PCR assay. (A) Schematic of the qsLAM PCR method for VIS analysis. Vector sequences are depicted in red, genomic sequences in blue, and adapter sequences as black boxes. Three individual shear sites for a single VIS are schematically represented. The relative locations of primers for linear PCR (P1), and nested PCR (P2 and P3) are shown. (B) Primer binding sites (in red) and the −24 to −5 sequences (inside the rectangle) of the LTR-U5 of the lentiviral vector that is used for reads specificity assessment are indicated. The red line at the end of the compliment primer represents the sequence required for Mi-Seq. qsLAM, quantitative shearing linear amplification; VIS, vector insertion site.

Sheared DNA ends were repaired to form blunt-ended DNA and 3′ dA tails were then added to the blunt ends. Adapter ligation was performed using the commercially available NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina kit that allows direct compatibility with the Illumina MiSeq system (Fig. 1). After adaptor ligation, 50 cycles of linear PCR were performed, which is then followed by streptavidin capture of a biotinylated primer homologous to the U5 LTR region of the CL20 lentiviral vector.29 Finally, 12 cycles of nested PCR were performed using a second set of primers that bind 23 bp from the end of U5 region and to the adaptor (Fig. 1B). The sequences that are required for Illumina MiSeq have been incorporated into the nested LTR-U5 primer, so that the only exponential PCR amplification used in qsLAM PCR protocol is a single round of 12 cycles of PCR. The final PCR products were mixed and then size-selected for the 250–800 bp fragments on a 2% E-gel (Supplementary Fig. S1). The resulting amplified templates are then directly processed according to protocol provided with the Illumina MiSeq instrument.

Generation of a standard human clonal cell line with multiple, defined lentiviral vector insertions

We transduced Jurkat cells, a widely available human T cell line, with our CL20-4i-EF1a-hγcOPT lentiviral vector26,30 at high multiplicity of 100 and isolated single cell clones with defined copy numbers. As a standard, we chose one clone containing 19 copies of the vector genome per cell when measured by qPCR and Southern blot analysis for proviral DNA genome copies. Initial qsLAM PCR mapping of the sequencing reads from this clone confirmed that there were a total of 19 copies of the vector genome inserted into 15 unique chromosomal locations, with 8 copies oriented as head-to-head juxtaposed pairs on opposite strands of four unique chromosomal locations (Table 1). The integration of lentiviral vectors as juxtaposed pairs has been reported previously in induced pluripotent stem cells.31

Table 1.

Characterization of 19 Unique Vector Insertion Sites in the Jurkat Clone

| Chromosome | Location | Unique shear site counts | Direction | Read counts | Vector insertion site ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chr16 | 782575 | 199 | + | 8160 | 7 |

| chr16 | 782577 | 298 | − | 22569 | 1 |

| chr4 | 32635317 | 131 | + | 5082 | 17 |

| chr4 | 32635318 | 246 | − | 10007 | 9 |

| chr11 | 32625911 | 189 | + | 8821 | 15 |

| chr11 | 32625913 | 234 | − | 9119 | 10 |

| chr16 | 53516510 | 188 | + | 9209 | 12 |

| chr16 | 53516512 | 252 | − | 8794 | 4 |

| chr19 | 10845881 | 226 | − | 6885 | 8 |

| chr3 | 15118930 | 264 | − | 18701 | 3 |

| chr17 | 15921192 | 165 | + | 6127 | 16 |

| chr21 | 33264264 | 175 | + | 9507 | 19 |

| chr15 | 59406223 | 243 | − | 10414 | 11 |

| chr2 | 61687568 | 170 | + | 5529 | 13 |

| chr11 | 67038560 | 256 | + | 18081 | 2 |

| chr12 | 97306744 | 94 | − | 2433 | 18 |

| chr5 | 109041904 | 187 | − | 10133 | 6 |

| chr4 | 133875590 | 226 | + | 7085 | 14 |

| chr1 | 235493350 | 199 | − | 12359 | 5 |

Unique shear site counts and read counts are from the spike-in internal Jurkat clone in the CD16+ sample.

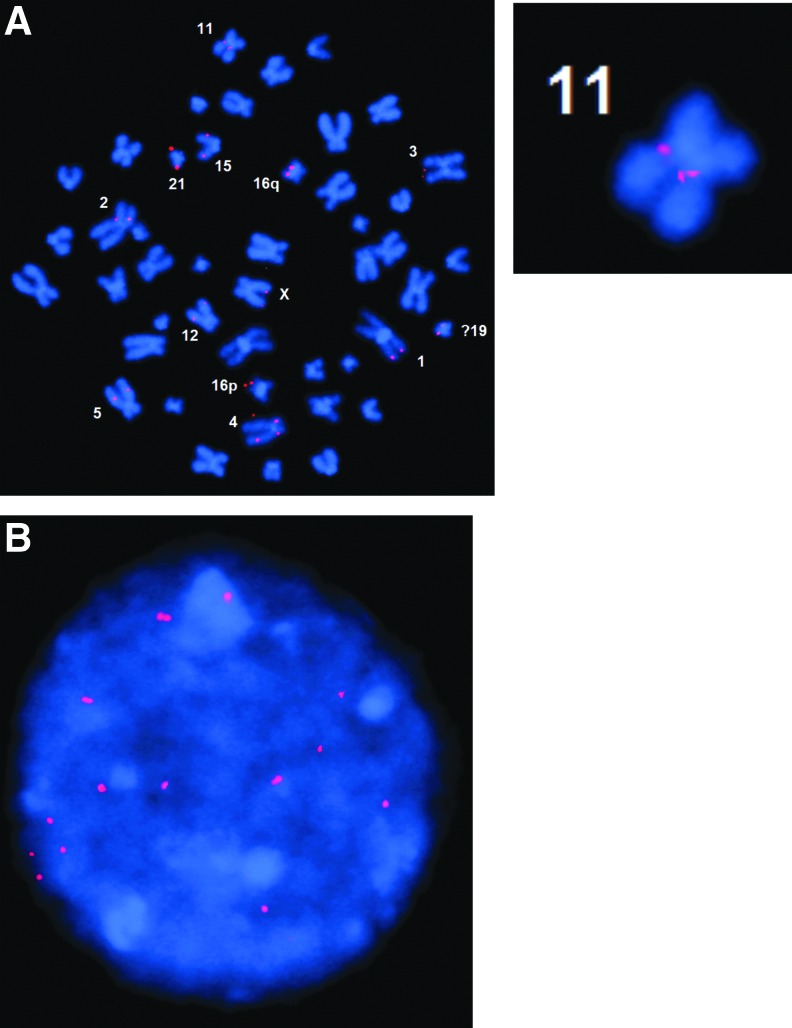

To further confirm the VIS information in this clone, we designed 19 pairs of primers flanking each VIS and performed PCR amplification, fragment size determination on a gel, and sequencing of the product to verify each VIS (data not shown). We have also performed fluorescent in situ hybridization of the clone using the entire lentiviral vector as probe and found 15 pairs of bright positive spots on metaphase chromosomes and interphase chromatin spreads (Fig. 2). Two distinct signals are seen on chromosome 11 demonstrating the two independent integrations seen on the sequencing analysis.

FIG. 2.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization of the 19 vector-copy Jurkat clone. The full-length vector plasmid was used as a probe and hybridized to either the metaphase (A) or interphase (B) cells. Chr11 is enlarged to show the two insertion site signals present.

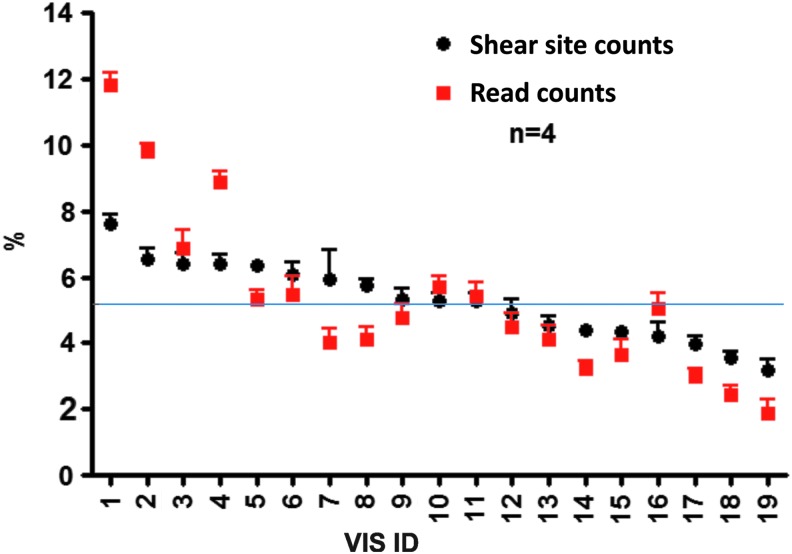

The qsLAM PCR technique was then used to estimate the read frequency for each of these 19 VIS events, which is expected to be 5.3% for each of the individual VIS present in this clone (1/19). When the total read counts for each VIS are compared, the read frequencies for each of the 19 VIS ranged between 1.88% and 11.84% (Fig. 3) over 4 independent experiments. When these data were analyzed based on the number of unique shear sites for each VIS, the shear site frequency range was smaller, measuring between 3.20% and 7.65% (Fig. 3). This narrower range was much closer to the expected 5.3% frequency for each VIS, demonstrating that using shear site counts instead of read counts provides a more quantitative estimation of VIS frequency. In particular, the majority of the VIS had measured frequencies very close to 5.3% using the shear site counts with less extreme variation seen compared with total read counts. The deviation from the expected 5.3% when using the shear site counts method is most likely caused by small differences in the susceptibility to sonication at each VIS in the DNA sample, while the larger deviation when using the read counts is most likely caused by different PCR efficiencies for different templates as well as intrinsic errors from the sonication bias.

FIG. 3.

Quantitation of VIS frequency in the Jurkat control clone. Comparison of the use of shear site counts (black circles) and read counts (red squares) for quantification of each of the 19 VIS present in the transduced Jurkat control clone. The data for shear sites or read counts are expressed as a percentage of the total sites/reads for each of the 19 VIS shown on the X axis. The data show the average of four independent experiments (four sonications and four corresponding qsLAM PCR) with error bars showing the standard deviation for each VIS measurement. The blue line shows the expected value for each of the 19 VIS (5.3%).

qsLAM PCR analysis of lentivirally transduced hematopoietic cells from human subjects

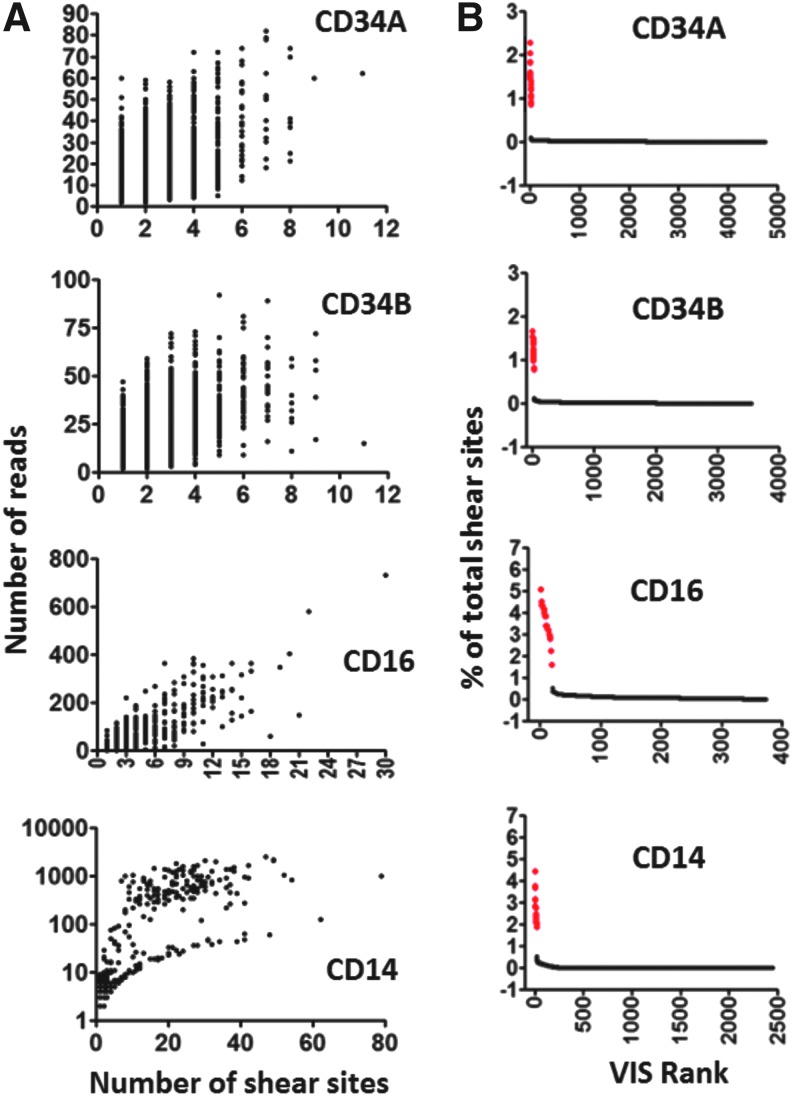

In order to assess the performance of qsLAM PCR on highly polyclonal populations of human hematopoietic cells, we obtained populations of human peripheral blood CD34+ cells from normal volunteers after G-CSF mobilization. These cells were then transduced with the CL20-4i-EF1a-hγcOPT vector being used in our LVXSCID clinical trials. Vector preparations were either generated from transient transfection of 293T cells (CD34A) or produced from our stable lentiviral vector producer clone 1A4 (CD34B).27 After transduction, the cells were cultured for an additional 5 days and genomic DNA was extracted for qsLAM PCR. The average VCN was 2.47 and 1.92 genomes per cell for the CD34A and CD34B populations, respectively, by qPCR. For both of these samples, we loaded 50 ng of sample in each MiSeq reaction out of a total of 1000 ng of the starting template. A total of 4730 and 3530 unique VIS were identified within the CD34A and CD34B populations, respectively.

We also collected peripheral blood mononuclear cells from a 24-year-old man with XSCID who had received gene therapy (NIAID Protocol #11-I-0007) with autologous lentivector (CL20-4i-EF1a- hγcOPT)-transduced CD34 cells to treat previously failed allogeneic transplantation. Peripheral blood samples were collected 3 months after transplantation and cell sorting was used to isolate CD14+ monocytes and CD16+ NK cells. Genomic DNAs were isolated from these samples and were shown to contain an average vector genome copy number of about 0.10 genomes per cell for both subpopulations. Subsequent qsLAM analysis with 250 ng each of these samples demonstrated a total of 354 unique VIS in the CD16 population and 2428 VIS in the CD14 population with one single qsLAM PCR run.

We then compared read counts versus unique shear sites as endpoints for measuring VIS frequencies in these four samples (Fig. 4A). For all VIS with a single unique shear site, the read counts varied between 1 and 60, directly demonstrating the variability in read counts introduced by differences in PCR amplification efficiency (Fig. 4A). The read count varied by more than an order of magnitude at most fixed points on the shear site distribution curves in all four samples, although there was a rough general correlation between shear site and read counts. This finding further supports the conclusion that the best quantitative measure for VIS frequencies is based on shear site counts rather than read counts.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of VIS in transduced human hematopoietic cells using qsLAM. (A) Relationship of shear site numbers with read count numbers in cultured human peripheral blood CD34+ cells transduced with a transiently produced lentiviral vector (CD34A), lentiviral vector produced in a stable cell line (CD34B), or in human peripheral blood samples from an XSCID gene therapy trial subject that were sorted for CD16 or CD14. Each dot represents an individual VIS present in the indicated sample. (B) Data from the test samples are here shown together with that from a 2% spike of DNA from the internal control Jurkat clone. This graph shows the percentage of total number of shear sites (Y axis) for each VIS present in the internal control sample (red dots) or from the polyclonal test samples (black dots). The X axis shows each of the VIS as individual columns ranked from most to least frequent going left to right as well as the total number of unique VIS.

Calculation of clonal abundance based on comparison with a spiked internal control clone

Genomic DNA from the 19-copy Jurkat control cell line was spiked into each of the 4 human patient samples at a 2% dilution ratio and shear sites were used to estimate clonal frequencies. In each of the 4 samples, all 19 of the control insertion sites were detected by qsLAM PCR at frequencies within a 3-fold range of variance (Fig. 4B). This result demonstrates that the assay is sensitive for semiquantitative clone size estimation at standard dilutions of only 2%. In all four human patient samples, the frequency of any VIS arising from the polyclonal test samples (black dots) was well below the VIS frequencies detected from the internal control sample (red dots).

In all four cases, the frequencies at individual VIS were evenly distributed across the entire VIS rank, showing that no single clone was dominant in any sample (Fig. 4B). This linear distribution was noted both in the highly polyclonal CD34 cell populations as well as in the samples derived from the clinical trial subject. In all cases, the frequencies of VIS from the test samples were less than that detected in the 2% spiked internal control sample. This would not be expected to be the case if a dominant clone were present in the test sample.

To further assess the sensitivity of the qsLAM PCR method, we spiked-in 1% (10 ng) and 0.2% (2 ng) of the 19-copy Jurkat DNA into 980 ng of each of the CD34A and CD34B samples and performed qsLAM PCR. The actual amount of the 19-copy Jurkat DNA that was used on MiSeq was 2.5 and 0.5 ng, respectively. In the 1% spike-in sample, all 19 VIS were retrieved; in the 0.2% spike-in sample, 18/19 VIS were retrieved (Supplementary Fig. S2), demonstrating that the qsLAM PCR is sufficiently sensitive. Noticeably, the quantitativeness of the method diminishes as the abundance of a given clone reduces.

Clonality analysis in two transplanted pigtail macaques using qsLAM PCR

We next evaluated qsLAM PCR in recipient pigtail macaques transplanted with split bone marrow CD34+ cell grafts that had been transduced either with a CL20-MSCV-mCherry vector or with a second CL20 vector expressing a growth-promoting gene and GFP. We intend to report the results for the GFP vector in a separate article (Bonner M et al., in preparation).

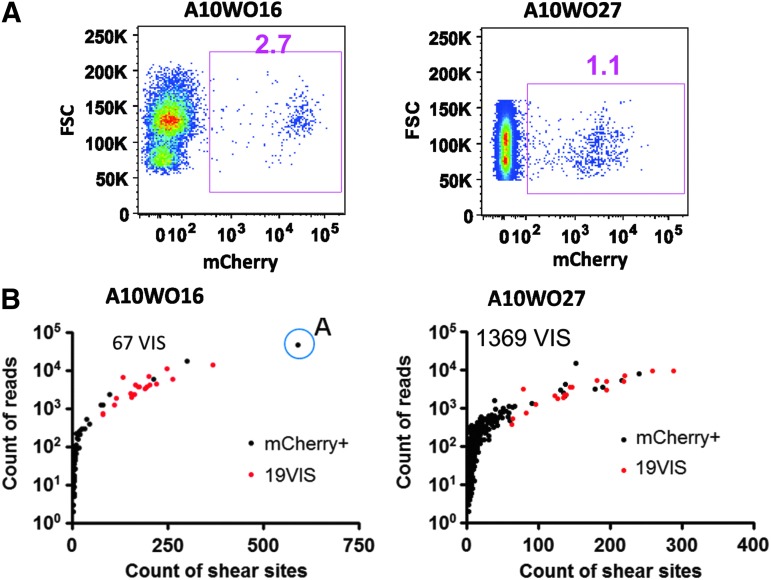

To define the clonal balance in cells arising from the mCherry marking vector, bone marrow cells were sorted for mCherry+ cells at 2 and 4 months after transplantation in animals A10WO16 and A10WO27, respectively. At that time, there were 2.7% and 1.1% mCherry+ cells in the bone marrow, respectively (Fig. 5A). DNA was prepared from the sorted cells and the internal control DNA was spiked in at 2% of the total DNA. In animal A10WO16, a total of 67 VIS were identified from a single run, while in animal A10WO27, 1369 VIS were identified from a single run. In both samples, all the 19 internal control VIS were identified at relatively high shear site and reads count, showing that the low number of VIS in A10WO16 was not because of technical reasons associated with the sample, but instead because of a significantly smaller number of transduced hematopoietic clones in the test sample (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Analysis of VIS in peripheral blood samples from transplanted pigtail macaques. (A) mCherry-expressing peripheral blood cells were sorted from two transplanted monkeys (A10WO17 and A10WO27) using the indicated sorting gates shown on this flow cytometry analysis. The percentages of mCherry+ cells are shown above each sorted population. (B) qsLAM PCR analysis of VIS from sorted peripheral blood samples. Black dots show individual VIS identified within the monkey samples and the number of VIS isolates from each animal is indicated. The red dots represent VIS from the internal control Jurkat clone, which was added to the monkey samples at a 2% dilution. The X axis shows the count of shear sites and the Y axis the read counts for each VIS. In animal A10WO16, a potentially dominant clone “A” was present and indicated by the blue circle.

One VIS (chr2:146296591, clone A) in A10WO16 comprises 57% of all the reads and was also associated with the highest number of unique shear sites, suggesting the relative dominance of this clone in transduced cells. This clone was larger than any of the 19 internal control VIS, establishing that it comprised greater than 2% of the total clonal size in the transduced sample. This VIS is mapped to the last exon of a transcript called Homo sapiens chromosome 3 open reading frame 58 (C3orf58), and no other transcripts or known genes were found within 160 kb of this VIS, suggesting that this VIS is most likely benign. We have designed primers flanking this VIS and performed PCR and independently confirmed the presence of this dominant clone (Supplementary Fig. S3).

A greater number of clones were seen in animal A10WO27 and none of these clones exceeded all the shear site counts arising from the internal control sample. This observation, together with the larger number of VIS retrieved in this animal, demonstrates that the diversity of transduced clones seen in monkey A10WO27 was significantly greater than that seen in A10WO16, despite the fact that A10WO27 was transplanted 2 months earlier than # 16. The relatively low clonal diversity in animal A10WO16 is best explained by infusion of a smaller number of reconstituting clones at the time of transplant. This interpretation is supported by the observation that hematopoietic reconstitution was slower and more prolonged in A10WO16. For instance, it took 14 days for animal A10WO16 to reach an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of 500 cells/μl, and 60 days to reach transfusion independence with 14 transfusions. In contrast, the ANC in animal A10WO27 reached 500 cell/μl in 12 days and transfusion independence was reached in only 35 days with 9 transfusions. This suggests that the occurrence of a dominant clone in animal A10WO16 is best explained by oligoclonal reconstitution because of transplantation with a relatively low number of transduced cells.

Discussion

We have developed a sensitive and semiquantitative method for VIS analysis by combining random DNA shearing, linear amplification, and inclusion of an internal control DNA sample with a known frequency of vector insertions. With only 20 ng of genomic DNA from the internal control clone, which was mixed with 980 ng of highly polyclonal sample, all 19 VIS can be retrieved at high read and shear site counts. The semiquantitative nature of this assay is demonstrated by the tight range of shear site frequencies for each of the 19 VIS (3.2–7.65%), which compares favorably to the expected frequency of 5.3% for each VIS. This accuracy and sensitivity was maintained even when the control was diluted to 2% of the total with highly polyclonal, marked samples. Our method only requires two unique PCR primers in total. All the other reagents are commercially available, including 24 barcoded primers in the NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina kit, which allows for multiplexing 24 samples in one run.

Several high-throughput methods have been developed for VIS analysis and they have contributed significantly to our understanding of vector integration biology and clonal evolution following transplant of HSCs.4,32–34 However, these methods sometimes lack quantitative standards and may not accurately measure clone size in all instances, particularly when restriction enzyme digestion is used to facilitate adapter ligation.13,17,35 Recently, random DNA shearing by sonication and count of shear site was introduced and appear to have better accuracy and sensitivity.20,21,23,28,36,37 We further improved this method by minimizing the number of exponential PCR cycles used for template generation and by including an internal control sample with a relatively high number of quantitatively defined VIS. The internal control allowed us to define the sensitivity, accuracy, and overall quality of each MiSeq run, and provides a standard for measuring clonal abundance in complex samples.

Our analysis also shows that the use of unique shear sites present within any given VIS generally provides a more accurate measurement of clone size compared with using read counts.20,24,28 This is most likely explained by potential biases in exponential PCR amplification of sonicated fragments from different VIS. While our data support the use of shear site counts in place of read counts, shear site counts could potentially underestimate the absolute abundance of a relatively large dominant clone because the number of different shear sites for a given VIS could be limited by the length of sheared DNA fragments.21 Therefore, the gold standard for measuring the frequency of dominant clones should remain being VIS-specific qPCR using primers specific for a given insertion site.18,38 Alternatively, random barcoding could be built into the adaptor to enhance the quantitativeness.

We have noticed a positive correlation between the GC content with both the read counts and shear site counts (Supplementary Fig. S4), suggesting that the GC content affects both the shearing efficiency and the relative PCR efficiency. Further improvements toward a sensitive and quantitative VIS analysis may include enrichment of fragments containing integrated vectors using hybrid capture methods, such as the SureSelect Target Enrichment System (Agilent Technologies), which could enhance sensitivity by reducing noise. Another approach is to use direct genome sequencing without PCR, which may be more feasible as the technology and computing power improves.35

When the qsLAM PCR assay was used to evaluate human CD34+ cells transduced with a clinical lentiviral vector, there were no clones that comprised more than 2% of the population as defined by the internal control signal strength. This is expected because it is known that many CD34+ cells are not repopulating cells and that the transduced bulk graft is highly polyclonal. The even distribution of the number of shear sites for all the VIS also demonstrates the lack of a dominant clone. When DNA samples from a gene therapy trial participant were studied with qsLAM PCR, we also noted that the distribution of VIS in these samples was continuous and that any single VIS compromised much less than 2% of the population, as defined by the internal control signals. This demonstrates the utility of qsLAM PCR for clinical trial monitoring for the emergence of dominant clones.

Spiking-in of various amounts (2%, 1%, and 0.2%) of the 19-copy Jurkat DNA into the test samples showed that our method is most accurate when the abundance of the clone is above 2%. As the abundance of the clone reduces, the ability of the assay to quantitate the clone size diminishes, although the method is still sufficiently sensitive to retrieve almost all clones well below the 2% abundance level. With these caveats, qsLAM can be used to reliably monitor the emergence of dominant clones that represent greater than 2% of the population.

Our VIS results in two transplanted nonhuman primates show different degrees of VIS distribution in the two cases. In the animal that experienced delayed hematopoietic reconstitution (A10WO16), a limited distribution was obtained that is somewhat reminiscent of the clonal dominance that occurred in a recent gene therapy trial for beta-thalassemia, in which a clone with the HMGA2 gene insertion comprised up to 45% of all the vector-bearing nucleated blood cells.8 However, the proportion of this clone in the total circulating nucleated blood cell population was only 3% and appears to have plateaued at this level, questioning whether apparent dominance was because of transplantation with a limited number of HSCs versus direct clonal expansion because of HMGA2 activation. Similarly, clone A in animal A10WO16 comprised about 57% of vector-bearing nucleated bone marrow cells and yet the total vector-bearing cells is only about 2.7% and declined to about 1% thereafter. Furthermore, the insertion site has no apparent proximity to a growth promoting gene that could cause this effect. Considering the slow reconstitution of ANC and platelet in animal A10WO16, the high proportion of clone A is most likely because of a relatively low number of transduced HSCs present in this animal. This latter interpretation is supported by the total count of unique VIS, which was only 67 in animal A10WO16 compared with 1369 in animal A10WO27. This illustrates how quantitative measurement of VIS by qsLAM can provide information about the relative diversity in the clonal repertoire in the transduced hematopoietic systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank John T. Gray for insightful discussions and advice, Chunlao Tang for data analysis, Virginia Valentine and Marc Valentine for fluorescence in situ hybridization, Dana Roeber and Scott Olsen for genome sequencing, and Taihe Lu for Southern blot analysis and PCR. This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Grant P01HL 53749), Cancer Center (Support Grant P30 CA 21765), the Assisi Foundation of Memphis, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist for any of the authors.

References

- 1.Dropulic B. Lentiviral vectors: their molecular design, safety, and use in laboratory and preclinical research. Hum Gene Ther 2011;22:649–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nienhuis AW, Dunbar CE, Sorrentino BP. Genotoxicity of retroviral integration in hematopoietic cells. Mol Ther 2006;13:1031–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trobridge GD. Genotoxicity of retroviral hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2011;11:581–593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun CJ, Boztug K, Paruzynski A, et al. Gene therapy for Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome—long-term efficacy and genotoxicity. Sci Transl Med 2014;6:227ra33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Garrigue A, Wang GP, et al. Insertional oncogenesis in 4 patients after retrovirus-mediated gene therapy of SCID-X1. J Clin Invest 2008;118:3132–3142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howe SJ, Mansour MR, Schwarzwaelder K, et al. Insertional mutagenesis combined with acquired somatic mutations causes leukemogenesis following gene therapy of SCID-X1 patients. J Clin Invest 2008;118:3143–3150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stein S, Ott MG, Schultze-Strasser S, et al. Genomic instability and myelodysplasia with monosomy 7 consequent to EVI1 activation after gene therapy for chronic granulomatous disease. Nat Med 2010;16:198–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavazzana-Calvo M, Payen E, Negre O, et al. Transfusion independence and HMGA2 activation after gene therapy of human beta-thalassaemia. Nature 2010;467:318–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu C, Dunbar CE. Stem cell gene therapy: the risks of insertional mutagenesis and approaches to minimize genotoxicity. Front Med 2011;5:356–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerrits A, Dykstra B, Kalmykowa OJ, et al. Cellular barcoding tool for clonal analysis in the hematopoietic system. Blood 2010;115:2610–2618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu R, Neff NF, Quake SR, et al. Tracking single hematopoietic stem cells in vivo using high-throughput sequencing in conjunction with viral genetic barcoding. Nat Biotechnol 2011;29:928–933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu C, Li B, Lu R, et al. Clonal tracking of rhesus macaque hematopoiesis highlights a distinct lineage origin for natural killer cells. Cell Stem Cell 2014;14:486–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabriel R, Eckenberg R, Paruzynski A, et al. Comprehensive genomic access to vector integration in clinical gene therapy. Nat Med 2009;15:1431–1436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim S, Kim N, Presson AP, et al. High-throughput, sensitive quantification of repopulating hematopoietic stem cell clones. J Virol 2010;84:11771–11780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paruzynski A, Arens A, Gabriel R, et al. Genome-wide high-throughput integrome analyses by nrLAM-PCR and next-generation sequencing. Nat Protoc 2010;5:1379–1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt M, Schwarzwaelder K, Bartholomae C, et al. High-resolution insertion-site analysis by linear amplification-mediated PCR (LAM-PCR). Nat Methods 2007;4:1051–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brugman MH, Suerth JD, Rothe M, et al. Evaluating a ligation-mediated PCR and pyrosequencing method for the detection of clonal contribution in polyclonal retrovirally transduced samples. Hum Gene Ther Methods 2013;24:68–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cornils K, Bartholomae CC, Thielecke L, et al. Comparative clonal analysis of reconstitution kinetics after transplantation of hematopoietic stem cells gene marked with a lentiviral SIN or a gamma-retroviral LTR vector. Exp Hematol 2013;41:28–38.e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harkey MA, Kaul R, Jacobs MA, et al. Multiarm high-throughput integration site detection: limitations of LAM-PCR technology and optimization for clonal analysis. Stem Cells Dev 2007;16:381–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beard BC, Adair JE, Trobridge GD, et al. High-throughput genomic mapping of vector integration sites in gene therapy studies. Methods Mol Biol 2014;1185:321–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berry CC, Gillet NA, Melamed A, et al. Estimating abundances of retroviral insertion sites from DNA fragment length data. Bioinformatics 2012;28:755–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brady T, Roth SL, Malani N, et al. A method to sequence and quantify DNA integration for monitoring outcome in gene therapy. Nucleic Acids Res 2011;39:e72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Ravin SS, Su L, Theobald N, et al. Enhancers are major targets for murine leukemia virus vector integration. J Virol 2014;88:4504–4513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koudijs MJ, Klijn C, Van Der Weyden L, et al. High-throughput semiquantitative analysis of insertional mutations in heterogeneous tumors. Genome Res 2011;21:2181–2189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu C, Jares A, Winkler T, et al. High efficiency restriction enzyme-free linear amplification-mediated polymerase chain reaction approach for tracking lentiviral integration sites does not abrogate retrieval bias. Hum Gene Ther 2013;24:38–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou S, Mody D, Deravin SS, et al. A self-inactivating lentiviral vector for SCID-X1 gene therapy that does not activate LMO2 expression in human T cells. Blood 2010;116:900–908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Throm RE, Ouma AA, Zhou S, et al. Efficient construction of producer cell lines for a SIN lentiviral vector for SCID-X1 gene therapy by concatemeric array transfection. Blood 2009;113:5104–5110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gillet NA, Malani N, Melamed A, et al. The host genomic environment of the provirus determines the abundance of HTLV-1-infected T-cell clones. Blood 2011;117:3113–3122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanawa H, Hargrove PW, Kepes S, et al. Extended beta-globin locus control region elements promote consistent therapeutic expression of a gamma-globin lentiviral vector in murine beta-thalassemia. Blood 2004;104:2281–2290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou S, Ma Z, Lu T, et al. Mouse transplant models for evaluating the oncogenic risk of a self-inactivating XSCID lentiviral vector. PLoS One 2013;8:e62333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winkler T, Cantilena A, Metais JY, et al. No evidence for clonal selection due to lentiviral integration sites in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells 2010;28:687–694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aiuti A, Biasco L, Scaramuzza S, et al. Lentiviral hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy in patients with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. Science 2013;341:1233151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cartier N, Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Bartholomae CC, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy with a lentiviral vector in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Science 2009;326:818–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang GP, Berry CC, Malani N, et al. Dynamics of gene-modified progenitor cells analyzed by tracking retroviral integration sites in a human SCID-X1 gene therapy trial. Blood 2010;115:4356–4366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Biasco L, Baricordi C, Aiuti A. Retroviral integrations in gene therapy trials. Mol Ther 2012;20:709–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Firouzi S, Lopez Y, Suzuki Y, et al. Development and validation of a new high-throughput method to investigate the clonality of HTLV-1-infected cells based on provirus integration sites. Genome Med 2014;6:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maldarelli F, Wu X, Su L, et al. HIV latency. Specific HIV integration sites are linked to clonal expansion and persistence of infected cells. Science 2014;345:179–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aiuti A, Cassani B, Andolfi G, et al. Multilineage hematopoietic reconstitution without clonal selection in ADA-SCID patients treated with stem cell gene therapy. J Clin Invest 2007;117:2233–2240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.