ABSTRACT

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) is an emerging tick-borne pathogen that was first reported in China in 2009. Phylogenetic analysis of the viral genome showed that SFTS virus represents a new lineage within the Phlebovirus genus, distinct from the existing sandfly fever and Uukuniemi virus groups, in the family Bunyaviridae. SFTS disease is characterized by gastrointestinal symptoms, chills, joint pain, myalgia, thrombocytopenia, leukocytopenia, and some hemorrhagic manifestations with a case fatality rate of about 2 to 15%. Here we report the development of reverse genetics systems to study STFSV replication and pathogenesis. We developed and optimized functional T7 polymerase-based M- and S-segment minigenome assays, which revealed errors in the published terminal sequences of the S segment of the Hubei 29 strain of SFTSV. We then generated recombinant viruses from cloned cDNAs prepared to the antigenomic RNAs both of the minimally passaged virus (HB29) and of a cell culture-adapted strain designated HB29pp. The growth properties, pattern of viral protein synthesis, and subcellular localization of viral N and NSs proteins of wild-type HB29pp (wtHB29pp) and recombinant HB29pp viruses were indistinguishable. We also show that the viruses fail to shut off host cell polypeptide production. The robust reverse genetics system described will be a valuable tool for the design of therapeutics and the development of killed and attenuated vaccines against this important emerging pathogen.

IMPORTANCE SFTSV and related tick-borne phleboviruses such as Heartland virus are emerging viruses shown to cause severe disease in humans in the Far East and the United States, respectively. Study of these novel pathogens would be facilitated by technology to manipulate these viruses in a laboratory setting using reverse genetics. Here, we report the generation of infectious SFTSV from cDNA clones and demonstrate that the behavior of recombinant viruses is similar to that of the wild type. This advance will allow for further dissection of the roles of each of the viral proteins in the context of virus infection, as well as help in the development of antiviral drugs and protective vaccines.

INTRODUCTION

The family Bunyaviridae is one of the largest taxonomic groupings of RNA viruses, containing over 350 named isolates that are classified into five genera: Hantavirus, Nairovirus, Orthobunyavirus, Phlebovirus, and Tospovirus (1). All viruses share a genome structure that comprises three segments of negative-sense or ambisense RNA, named small (S), medium (M), and large (L). The S segment encodes the nucleocapsid (N) protein; the M segment encodes the virion glycoproteins Gn and Gc; and the L segment encodes the L protein, the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Some viruses also encode nonstructural proteins on the S and M segments. Viruses that impinge on human health, either directly by causing human disease or indirectly by causing economic losses of domestic animals or crop plants, are found in each of the five genera and provide many examples of “emerging diseases” (reviewed in references 2, 3, and 4).

In the latest report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, the Phlebovirus genus contains 70 viruses, which comprise 9 species and 33 tentative species (1). Phleboviruses can be divided into 2 groups: (i) the sandfly fever group, which includes notable pathogens such as Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV), Sicilian sandfly fever virus, and Toscana virus, which are transmitted by dipterans (sandflies and mosquitoes); and (ii) the Uukuniemi virus (UUKV) group viruses, which are instead transmitted by ticks (5). UUKV was isolated from Ixodes ricinus ticks in Finland and has subsequently been found across Central and Eastern Europe. UUKV and related viruses have not been associated with human disease (6). The best-characterized phlebovirus in terms of both molecular biology and pathogenesis is RVFV, which is also a severe pathogen of ruminants, frequently causing large epidemics and “abortion storms” among pregnant animals (5, 7–9).

Between 2007 and 2010, cases of an unknown infectious disease were reported in Henan and Hubei Provinces, China, with patients presenting gastrointestinal signs and symptoms, chills, joint pain, myalgia, thrombocytopenia, leukocytopenia, and some hemorrhagic manifestations, resulting in a case fatality rate of 12 to 30% (10). (Since the initial report, the current case fatality in China is estimated at 2 to 15% [11, 12]). The disease was originally suspected to be anaplasmosis, but some clinical signs and symptoms were inconsistent with this diagnosis. Subsequently, studies by different groups in China involving virus isolation in cell culture, genome amplification and sequencing, and metagenomic analysis of patient material revealed the presence of a novel bunyavirus that was most closely related to the phleboviruses. Importantly, the sequence data showed no evidence for an NSm protein upstream of the Gn-Gc precursor encoded by the M genome segment, which is a hallmark of the Uukuniemi virus group (13). The virus has been variously called DaBie Mountain virus (10, 14), Henan fever virus (15), Huaiyangshan virus (16), and severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) (10). The International Committee for Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) Executive Committee has recommended that the species name encompassing these viruses be SFTS virus, a proposal awaiting ratification by the ICTV membership.

Both SFTSV and viral RNA have been isolated from Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks, and viral RNA has been detected in Rhipicephalus microplus ticks gathered from domestic animals in China (10, 16). Detection of SFTSV RNA was highest in H. longicornis, a species that has a widespread geographical distribution outside China including Korea, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific Islands (17). The subsequent reports of SFTSV-positive ticks and confirmed cases of disease in South Korea (18, 19) and Japan (20) indicate that SFTSV and SFTSV-like viruses may have a broad geographical distribution.

Recently, other novel tick-transmitted phleboviruses have been characterized (reviewed in reference 21). Heartland virus (HRTV) was isolated from two patients in Missouri, USA, who experienced fever, fatigue, anorexia, diarrhea, and thrombocytopenia. Deep sequencing of total RNA from tissue culture cells inoculated with the patients' blood revealed a novel phlebovirus that clustered phylogenetically with SFTSV (22). However, HRTV is quite distinct from SFTSV, showing 27% and 38% differences in the viral RNA polymerase and N protein sequences, respectively. HRTV has been isolated from Amblyomma americanum ticks, implicating this tick as the likely primary vector for transmission of the virus within the United States (23). A further six cases of HRTV infection have since been described (24).

In addition, contemporary genetic analyses of some previously uncharacterized tick-borne bunyaviruses have now shown them to be phleboviruses related to SFTSV and HRTV. The Bhanja virus (BHAV) antigenic complex (Bhanja, Forecariah, Kismayo, and Palma viruses) comprises tick-borne viruses that were assigned to the family Bunyaviridae but were not further classified into a genus. BHAV was isolated in India in 1954 from a tick on a paralyzed goat and causes fever and signs of central nervous system involvement in young ruminants but not in adult animals. A few cases of febrile illness in humans have been described, and serological surveys in Eastern Europe suggest that BHAV is endemic in that region and may cause undetected human infection (6, 25). Two recent papers report nucleotide sequence determination of Bhanja group viruses (26, 27) and show that they are related to SFTSV and HRTV. Lone Star virus (LSV) was originally isolated from A. americanum (the lone star tick) in Kentucky in 1967 (28) and, like BHAV, was an unclassified member of the Bunyaviridae. The sequence of the viral genome has recently been determined by deep sequencing and shown to be in the same clade as BHAV (29). LSV can infect human (HeLa) and monkey (Vero) cells in culture, but there is no evidence for human infection. A novel phlebovirus called Malsoor virus that is phylogenetically related to SFTSV and HRTV has been reported from bats in India (30); whether Malsoor virus is tick borne is not known. Lastly, Hunter Island Group virus has been isolated from ticks associated with shy albatrosses in Australia (31). The zoonotic potential of these viruses (Malsoor and Hunter Island Group viruses) is unknown. Thus, there is now an expanding group of related and globally distributed tick-borne phleboviruses that range from being apathogenic in humans (UUKV) through mildly pathogenic (BHAV) to severely pathogenic (SFTSV, HRTV).

An important tool for exploring the molecular biology and pathogenesis of RNA viruses and also for vaccine development is reverse genetics, defined as the ability to generate recombinant viruses from cloned cDNA (32). Here we report the development of a T7 RNA polymerase-based reverse genetics system for SFTSV. We first established a minigenome system, which led to correction of the published sequence of the SFTSV S segment (strain Hubei 29 [HB29]). Then, we generated full-length cDNA clones to HB29 from both minimally passaged and cell-culture-adapted virus stocks, the latter containing a few amino acid changes in the M- and L-segment-encoded proteins. Growth properties of the recombinant viruses were studied along with analysis of viral protein synthesis, host cell protein synthesis inhibition, and examination of the subcellular localization of the viral proteins. We discuss the implications of creating a reverse genetics system for SFTSV for the study of this newly emerging pathogenic phlebovirus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Vero E6 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). BSR-T7/5 cells (33), which stably express T7 RNA polymerase, were grown in Glasgow minimal essential medium (GMEM) supplemented with 10% FCS, 10% tryptose phosphate broth, and 1 mg/ml G418. HuH7-Lunet-T7 cells (34), which also stably express T7 RNA polymerase, were obtained from R. Bartenschlager and were grown in DMEM supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, nonessential amino acids, and 10% FCS. All mammalian cell lines were grown at 37°C with 5% CO2 unless otherwise stated.

Minimally passaged Hubei 29 (HB29) virus (isolated from human serum of a 61-year-old female, 9 days following the onset of disease; Hubei province, China, 2010) was grown only in the Beijing laboratory. The plaque-purified cell culture-adapted strain, designated Hubei 29pp (HB29pp), was supplied to the Glasgow laboratory via the CDC Arbovirus Diseases Branch, Division of Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases, Fort Collins, CO, courtesy of Amy Lambert.

In Beijing, all experiments with infectious virus were conducted in a biosafety level 2 plus (BSL-2 Plus) facility under negative pressure, as approved by the Chinese Ministry of Health, and in Glasgow under containment level 3 (CL3) conditions as approved by the UK Health and Safety Executive. Stocks of recombinant viruses were grown in Vero E6 cells at 37°C by infecting at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI) and harvesting the culture medium at 7 days postinfection (p.i.).

Total cell RNA extraction and RT-PCR.

Vero E6 cells were infected at an MOI of 0.01, and total cellular RNA was extracted at 72 h p.i. using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). For reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), 1 μg of total cellular RNA was mixed with a segment-specific oligonucleotide (Table 1), 0.5 mM 4× deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) mix (Promega), 40 U rRNasin (Promega), and 200 U Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MLV) reverse transcriptase (Promega) and incubated at 42°C for 3 h. The resulting cDNA was used in PCRs with primers described in Table 1, and the products were visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis. Products of the correct size were excised from the gel and purified using Wizard SV Gel & PCR Clean-Up System (A9282; Promega), followed by direct nucleotide sequencing of the PCR product.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used for the construction of HB29 cDNA clones

| Segment and clone | Sequence (5′–3′)a |

|---|---|

| S segment | |

| HB29SforT7+ | GAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGacacaaagaAcccccaaaaaaggaaag |

| HB29SforT7− | GGAGATGCCATGCCGACCCacacaaagAacccccttcatttggaaac |

| M segment | |

| HB29MforT7+ | GAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGacacagagacggccaacaatgatg |

| HB29MforT7− | GGAGGTGGAGATGCCATGCCGACCCacacaaagaccggccaacacttcaatag |

| L segment | |

| HB29LforT7+ | GAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGacacagagacgcccagatgaacttgg |

| HB29LforT7− | GGAGGTGGAGATGCCATGCCGACCCacacaaagaccgcccagatcttaagg |

| N ORF | |

| HB29pTM1N+ | CTTTGAAAAACACGATAATACCatgtcggagtggtccaggattg |

| HB29pTM1N− | CTTAATTAATTAGGCCTCTCGAGttacaggtttctgtaagcagcagcag |

| L ORF | |

| HB29pTM1L+ | CTTTGAAAAACACGATAATACCatgaacttggaagtgctttgtg |

| HB29pTM1L− | CTTAATTAATTAGGCCTCTCGAGttaaccccacataatggtgctc |

Underlined, T7 promoter sequence; italics, hepatitis delta ribozyme sequence; bold, 5′ cloning site of pTM1; italics and underlined, 3′ cloning site of pTM1; uppercase, vector-derived sequences; lowercase, viral sequences.

3′ RACE.

3′ RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) analysis was used to obtain both the 3′ and 5′ terminal sequences using strand-specific primers. Briefly, virion RNA was isolated from supernatants using a QIAamp Viral RNA minikit (52904; Qiagen), polyadenylated (AM1350; Ambion) for 1 h at 37°C, and then purified using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). Twelve microliters of polyadenylated RNA was then used in a reverse transcription reaction with M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega) and 100 μM oligo(dT) primer for 10 min at 65°C, followed by PCR using 0.3 μM 3′ RACE anchor primer and 0.3 μM segment-specific primer (Table 2) with KOD Hot Start DNA polymerase (Merck). Amplified products were purified on an agarose gel and their nucleotide sequences determined.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used for 3′ RACE analysis

| Primer for: | Sequence (5′–3′)a | Genome position (nt) (genomic RNA) |

|---|---|---|

| S segment | ||

| S-PCR (G) | GATCTCAGGTAACCCAAGTCTAAGCCTC | 518–545 |

| S-PCR sequence (G) | TCAACGAGGTCTCTCCTGAGAGTGGGGTAC | 116–145 |

| S-PCR (AG) | GCGCATCTTTACATTGATAGTCTTGGTGAAGGC | 1346–1373 |

| S-PCR sequence (AG) | CTGCAGCAGCACATGTCCAAGTGGGAAG | 1146–1178 |

| RACE-AP | GACCACGCGTATCGATGTCGAC | NAb |

| Oligo(dT) | GACCACGCGTATCGATGTCGACTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTV | NA |

V is nucleotide A, C, or G.

NA, not applicable.

Plasmids.

Plasmids for the recovery of SFTSV strains HB29 and HB29pp were created based on the previously described system for RVFV (35). Briefly, the QIAamp Viral RNA minikit (Qiagen) was used to extract viral RNA from supernatants of infected cells, and cDNAs were amplified through segment-specific RT-PCR. Viral antigenomic cDNAs were cloned into TVT7R (0, 0) (36) linearized with BbsI. Nucleocapsid protein and viral RNA polymerase open reading frames (ORFs) were cloned into EcoRI-linearized pTM1 vector by In-Fusion HD restriction-free cloning (Clontech) (Table 1). pTM1-HB29L (or pTM1-HB29ppL) and pTM1-HB29N contain the L and N ORFs under the control of T7 promoter and encephalomyocarditis virus internal ribosome entry site sequence; pTVT7-HB29S, pTVT7-HB29M, pTVT7-HB29ppM, pTVT7-HB29L, and pTVT7-HB29ppL contain full-length cDNAs in antigenome sense orientation flanked by T7 promoter and hepatitis delta ribozyme sequences.

Plasmid pTVT7-HB29M:F300S contains a full-length cDNA to the HB29 M segment in which nucleotide 1007 is mutated from thymine to cytosine, resulting in a change of amino acid from phenylalanine to serine at position 330 in the M segment polyprotein (F330S).

Plasmids expressing HB29-derived minigenomes were created, similar to those previously described for RVFV (37–39). The M-segment-based construct contains the humanized Renilla (hRen) gene ORF sequence in negative sense flanked by full-length genomic sense untranslated region (UTR) sequences in TVT7R (0, 0) and was called pTVT7-HB29M:hRen. In the S-segment-based minigenome, the sequence of the NSs ORF was replaced with either that of the hRen or the enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) ORF, with the reporter gene transcribed in the negative sense (called pTVT7-HB29SdelNSs:hRen and pTVT7-HB29SdelNSs:eGFP, respectively). The UTR sequences in the S-segment minigenome plasmids were subsequently corrected to insert the additional nucleotides at either end.

Minigenome assay.

BSR-T7/5 cells were transfected with various concentrations of pTM1-HB29N and 0.5 μg pTM1-HB29ppL or various concentrations of pTM1-HB29ppL and 0.5 μg pTM1-HB29N, together with the M-segment minigenome plasmid pTVT7-HB29M:hRen (1.0 μg) and pTM1-FF-Luc (0.01 μg) as a transfection control (40). Empty pTM1 vector was used to ensure that the total amounts of DNA (2.51 μg) transfected into the cells were equal. To test the effect of the corrected S-segment UTR sequences on S-based minigenome activity, BSR-T7/5 cells were transfected with 0.1 μg pTM1-HB29ppL and 0.5 μg pTM1-HB29N, together with 1.0 μg of the S-based reporter plasmid pTVT7-HB29SdelNSs:hRen based on the published sequence or with plasmids in which one or both UTRs had been corrected. At 24 h posttransfection, Renilla and firefly luciferase activities were measured using the Dual-Luciferase Assay kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Generation of recombinant viruses from cDNA.

Recombinant viruses were generated by transfecting 7.5 × 105 BSR-T7/5 cells or 5 × 105 HuH7-Lunet-T7 cells with 0.1 μg pTM1-HB29ppL, 0.5 μg pTM1-HB29N, and 1 μg each pTVT7-based plasmid expressing the viral antigenomic segments, using 3 μl TransIT-LT1 (Mirus Bio LLC) per μg of DNA as transfection reagent. After 5 days, the virus-containing supernatants were collected, clarified by low-speed centrifugation, and stored at −80°C. Stocks of recombinant viruses were grown in Vero E6 cells at 37°C by infecting at an MOI of 0.01 and harvesting the culture medium at 7 days p.i. The genome segments of the recovered viruses were amplified by RT-PCR, and their nucleotide sequences were determined to confirm that no mutations had occurred.

Production of SFTSV anti-N and anti-NSs antibodies.

The coding sequences for HB29 N and NSs proteins were amplified by PCR and cloned into modified pDEST14 vector (Invitrogen) using SacI restriction site for SFTSV N and SacI and XhoI restriction sites for SFTSV NSs. The generated plasmids p14SFTSV N and p14SFTSV NSs contain an N-terminal hexahistidine (6-His) tag for purification and a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease site (for removal of the 6-His tag). N and NSs proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 Rosetta2 (Merck) with IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) induction at 20°C for 18 h as described previously (37). Recombinant N protein was purified using Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) resin. Recombinant NSs was totally insoluble, and the specific NSs protein band was isolated from an SDS-PAGE gel after Coomassie blue staining. The identities of the purified N in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and NSs protein in gel bands were confirmed by mass spectrometry, and the proteins were used for generating rabbit polyclonal monospecific antibodies (Eurogentec).

Virus titration by plaque assay or immunostaining.

Vero E6 cells were infected with serial dilutions of virus and incubated under an overlay consisting of DMEM supplemented with 2% FCS and 0.6% Avicel (FMC BioPolymer) at 37°C for 7 days. Cell monolayers were fixed with 4% formaldehyde. Following fixation, cell monolayers were either stained with Giemsa to visualize plaques or subjected to immunofocus-staining assay. For the latter, cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100–PBS for 30 min at room temperature, washed once in PBS, and subjected to reaction with a 1:500 dilution of anti-HB29 N antiserum in buffer (PBS containing 4% dry milk and 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h. This was followed by incubation with 1:1,000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Technology). Visualization of viral foci was accomplished by using TrueBlue Peroxidase Substrate (InSight Biotechnology).

Western blotting.

At different time points after infection, cell lysates were prepared by the addition of 300 μl lysis buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 200 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.2% bromophenol blue, and 25 U/ml Benzonase [Novagen]), and proteins were separated on an SDS–4 to 12% gradient polyacrylamide gel (NuPAGE; Invitrogen). Proteins were transferred to a Hybond-C Extra membrane (Amersham), and the membrane was blocked by incubating in saturation buffer (PBS containing 5% dry milk and 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h. The membrane was incubated with HB29 anti-N and anti-NSs polyclonal rabbit antibodies or an antitubulin monoclonal antibody (Sigma). This was followed by incubation with either goat anti-rabbit DyLight 680 conjugate or goat anti-mouse DyLight 800 antibodies (35568 and 35521, respectively; Thermo Scientific). Visualization of detected proteins was achieved by scanning on a Li-Cor Odyssey CLx infrared imaging system.

Metabolic radiolabeling.

Vero E6 cells were infected at an MOI of 5. At the time points indicated, cells were incubated in starvation medium lacking methionine for 30 min, washed, and then labeled with [35S]methionine/cysteine (30 μCi/ml; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) for 2 h. Cell lysates were prepared by the addition of 300 μl lysis buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 200 mM DTT, 0.2% bromophenol blue, and 25 U/ml Benzonase [Novagen]), and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE as described above. Visualization of labeled proteins was achieved by exposure to a Storm840 Phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences of the HB29pp genome segments have been deposited in the GenBank database with accession numbers KP202163(L segment), KP202164 (M segment), and KP202165 (S segment).

RESULTS

Virus strains used in this study.

Full-length cDNA clones were generated from viral RNA from two sources: a minimally passaged stock of SFTSV strain Hubei 29, which is the original isolate as described in reference 10, and a plaque-purified cell culture-adapted stock, called Hubei 29pp (HB29pp; M. Liang, unpublished data), which was obtained following a further 4 passages in Vero cells of the original isolate. HB29pp generates large immunostained foci as well as large plaques in Vero cells, whereas the original isolate forms small immunostained foci and pinpoint-sized plaques. Nucleotide sequence determination of the HB29pp genome revealed several nucleotide changes in both the M and L RNA segments leading to four amino acid changes in the glycoprotein precursor, and one amino acid change was found in the L protein (Table 3), compared to the original isolate. No nucleotide substitutions were found in the S segment, though 2 missing nucleotides were identified in the S segment UTRs as described in more detail below.

TABLE 3.

Nucleotide and amino acid changes between SFTSV isolates HB29 and HB29pp

| Segment | Positiona | Location | Nucleotide in: |

Amino acid in: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HB29 | wtHB29pp | HB29 | wtHB29pp | ||||

| S | 10 | 5′ UTR | —b | A | NAc | ||

| 1738 | 3′ UTR | — | T | NA | |||

| M | 980 | Gn | C | T | Thr | Met | |

| 1400 | Gn | T | C | Leu | His | ||

| 1698 | Gc | A | T | Ala | |||

| 2828 | Gc | G | A | Ser | Asn | ||

| 2902 | Gc | C | A | Arg | Ser | ||

| L | 3682 | L | A | G | Leu | ||

| 4039 | L | T | C | Tyr | |||

| 4066 | L | T | C | Ala | |||

| 4102 | L | A | G | Val | |||

| 4219 | L | G | A | Lys | |||

| 6242 | L | G | A | Asp | Asn | ||

Numbers refer to the viral antigenomic sense.

—, nucleotide absent.

NA, not appropriate.

Development of a T7-driven minigenome system for SFTSV and correction of the Hubei 29 S segment sequence.

Bunyavirus minigenomes comprise a reporter gene, such as luciferase, cloned in the negative sense between the 3′ and 5′ untranslated regions of a viral segment, under the control of T7 promoter and hepatitis ribozyme sequences (41). When transfected into cells expressing T7 RNA polymerase, a negative-sense genome analogue is transcribed (the minigenome), and in the presence of coexpressed viral N and L proteins, a functional ribonucleoprotein that allows viral transcription and replication to be assessed by reporter gene activity is produced.

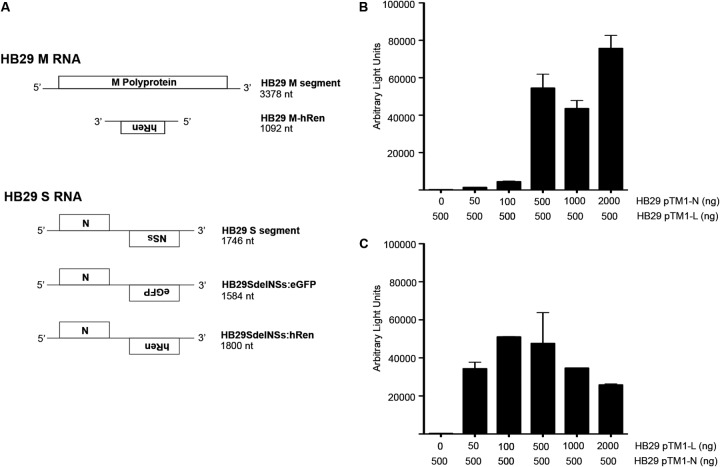

Therefore, an HB29 M-segment-based minigenome containing the humanized Renilla (hRen) luciferase gene was created and designated pTVT7-HB29M:hRen (Fig. 1A). BSR-T7/5 cells, which express T7 RNA polymerase, were transfected with 1,000 ng pTVT7-HB29M:hRen along with 500 ng of pTM1-HB29L and increasing amounts of pTM1-HB29N (Fig. 1B) or with 500 ng pTM1-HB29N and increasing amounts of pTM1-HB29L (Fig. 1C). Increasing amounts of nucleocapsid protein in the system generally led to an increase in minigenome activity (Fig. 1B), whereas there was a clear optimal amount of the L protein-expressing plasmid (100 ng) when using 500 ng pTM1-HB29N (Fig. 1C). Importantly, these data also show that the cDNA clones of both the viral N and L genes were functional, an important prerequisite to establish a viral rescue system.

FIG 1.

Creation of HB29 S- and M-based minigenome constructs. (A) Schematic of the genome organization of S- and M-based minigenome constructs and the relative orientation of the open reading frames in the transcription plasmids pTVT7. (B) Effect of increasing amounts of pTM1-HB29N on M-segment minigenome assay. BSR-T7/5 cells were transfected with pTVT7-HB29M:hRen, pTM1-HB29ppL, pTM1-FF-Luc, and the indicated amount of pTM1-HB29N. (C) Effect of increasing amounts of pTM1-HB29ppL on M-segment minigenome assay. BSR-T7/5 cells were transfected with pTVT7-HB29M:hRen, pTM1-HB29N, pTM1-FF-Luc, and the indicated amount of pTM1-HB29ppL. In both cases, empty pTM1 vector was used to ensure that the total amount of DNA used in each transfection was the same (2.51 μg). Renilla luciferase activity was measured 24 h posttransfection.

We also generated S-segment-based minigenomes in which the NSs ORF was replaced with either hRen or eGFP genes (Fig. 1A), using the UTR sequences originally reported for HB29 (GenBank accession no. HM745932), However, despite the success with the M-segment-based minigenome, no Renilla luciferase activity could be detected in transfected BSR-T7/5 cells with this S segment minigenome at any ratio of N to L expressing plasmid tested.

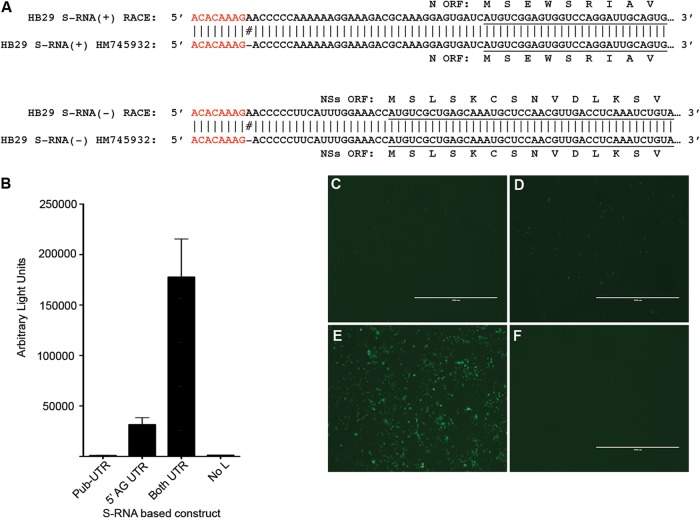

This prompted us to reexamine the UTR sequences of the S segment. Virion RNA was prepared from the supernatant of cells infected with either the original HB29 or HB29pp stocks and subjected to 3′ RACE analysis. As it had been shown previously for other phleboviruses that both genomic and antigenomic copies could be packaged into virions (42–44), we expected to be able to determine the 3′ UTR sequences of both polarities of RNA. Sanger sequencing of RACE products confirmed that the M and L RNA segment untranslated regions were as described for GenBank accession no. HM745931 and HM745930, respectively. However, for the S segment, we found an additional A residue at position 9 and an additional U residue at position 1737 compared to the database entry HM745932 (Fig. 2A). Based on these results, new versions of the HB29 S segment minigenomes were created, containing either the corrected antigenomic 5′ UTR (5′ AG UTR) or both UTRs (Both UTR) corrected, and compared to the original construct (Pub UTR) (Fig. 2B). Minigenome assays were set up using 500 ng pTM1-HB29N and 100 ng pTM1-HB29L, as optimized for the M segment minigenome. The addition of the A residue to the S segment antigenomic 5′ UTR showed a marked increase in minigenome activity compared to the original S segment minigenome, and when both UTRs were corrected, minigenome activity showed a substantial increase in activity. Similarly, we compared GFP expression from analogous minigenome constructs (Fig. 2C to F). No eGFP autofluorescence was seen with the minigenome with the published UTR sequences (Fig. 2C), and few eGFP-expressing cells could be observed when just the 5′ UTR sequence was corrected (Fig. 2D). However, when both UTRs were corrected, cells exhibited robust eGFP autofluorescence 24 h after transfection (Fig. 2E). Cells transfected with the functional minigenome but lacking the L-expressing plasmid showed no eGFP signal (Fig. 2F). These data indicate that the newly determined UTR sequences, with an additional nucleotide at each end, represent the functional S segment promoters.

FIG 2.

Correction of the sequence of the S-segment-based minigenome. (A) Schematic representation of 3′ RACE data indicating that there is a missing A residue at position 9 of both the 5′ and 3′ S segment UTRs. Conserved terminal nucleotides are highlighted in red, and open reading frames for N and NSs proteins are underlined. (B) Effect of correcting the S-segment UTR sequence on S minigenome activity. BSR-T7/5 cells were transfected with pTM1-HB29N, pTM1-HB29ppL, pTM1-FF-Luc and contained either the published UTR sequences (Pub-UTR) or pTVT7-HB29SdelNSs:hRen with an A residue inserted at position 9 of the 5′ antigenomic UTR (5′AG UTR) or pTVT7-HB29SdelNSs:hRen with A and T residues inserted at position 9 of both 5′ and 3′ UTRs (Both UTR). “No L” is a negative control without pTM1-HB29ppL (empty pTM1 vector was used instead). Renilla luciferase activity was measured 24 h posttransfection. (C to F) eGFP autofluorescence observed in cells 24 h after transfection with analogous minigenome plasmids containing eGFP in place of hRen sequences: HB29 S with published UTR sequences (C); A residue inserted at position 9 of the 5′ antigenomic UTR (D); A and T residues inserted at position 9 of both 5′ and 3′ UTRs (E); negative control without pTM1-HB29ppL (F).

NSs inhibition of minigenome activity.

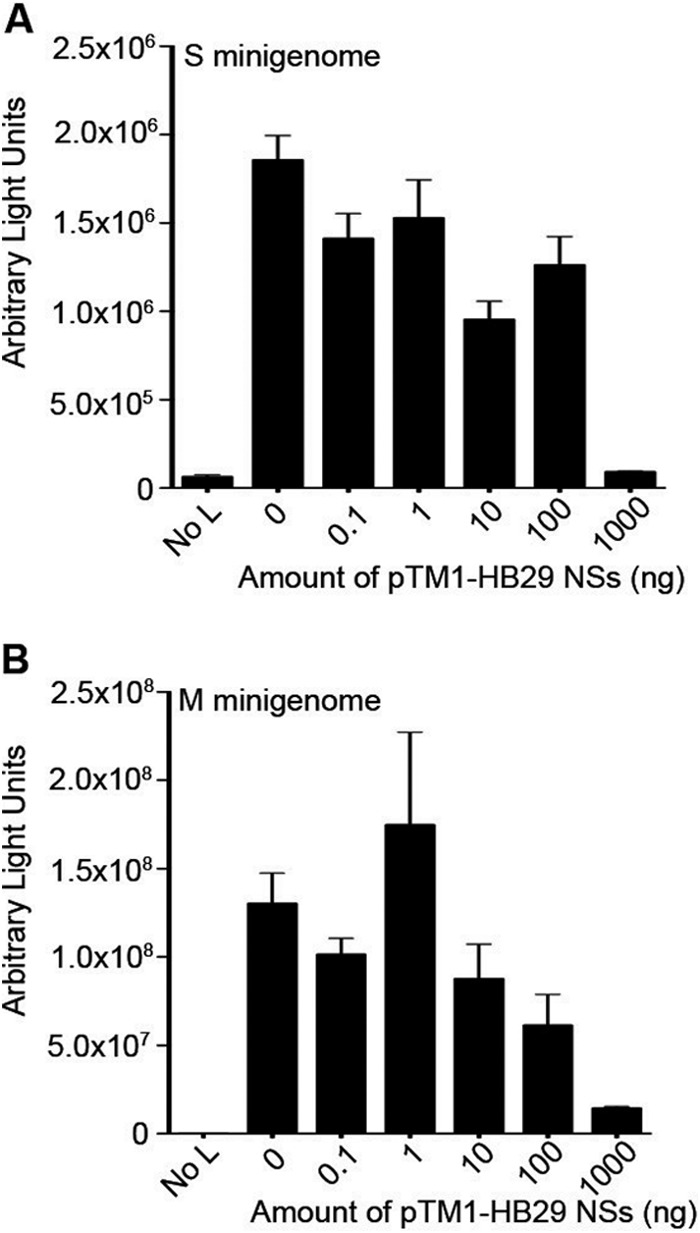

It has been reported previously that the NSs proteins of both Bunyamwera orthobunyavirus (BUNV) and RVFV (37, 40) inhibit the viral polymerase as measured by minigenome assays. SFTSV NSs forms distinct punctate structures in the cytoplasm of infected or plasmid-transfected cells (45–48). The NSs structures have been shown to colocalize with N protein and to be associated with viral RNAs, suggesting that NSs plays a role in the replication of the virus (47). To investigate whether HB29 NSs affects the viral polymerase, S- or M-segment-based minigenome plasmids (1,000 ng of either pTVT7-HB29SdelNSs:hRen or pTVT7-HB29M:hRen, respectively) were transfected into BSR-T7/5 cells along with 500 ng pTM1-HB29N, 100 ng pTM1-HB29L, and increasing concentrations of pTM1-HB29NSs (from 0.1 to 1,000 ng). As seen in Fig. 3A and B, Renilla luciferase activity was significantly inhibited only when the largest amount of pTM1-HB29NSs was added. While this inhibitory effect of NSs on the minireplicon was reproducible, the effect was not as dramatic or as inherently dose dependent as that described for BUNV or RVFV minigenomes, in which even small amounts of NSs-expressing plasmid showed marked inhibition.

FIG 3.

Effect of HB29 NSs protein on minigenome activity. BSR-T7/5 cells were transfected with pTM1-HB29ppL, pTM1-HB29N, pTM1-FF-Luc, the indicated increasing amounts of pTM1-HB29NSs, and either pTVT7-HB29SdelNSs:hRen (A) or pTVT7-HB29M:hRen (B). No L, negative control without pTM1-HB29ppL; empty pTM1 vector was used to ensure that equal amounts of DNA were transfected into each reaction mixture. Luciferase activities were measured at 24 h posttransfection.

Recovery of infectious virus from cDNA clones derived from minimally passaged HB29.

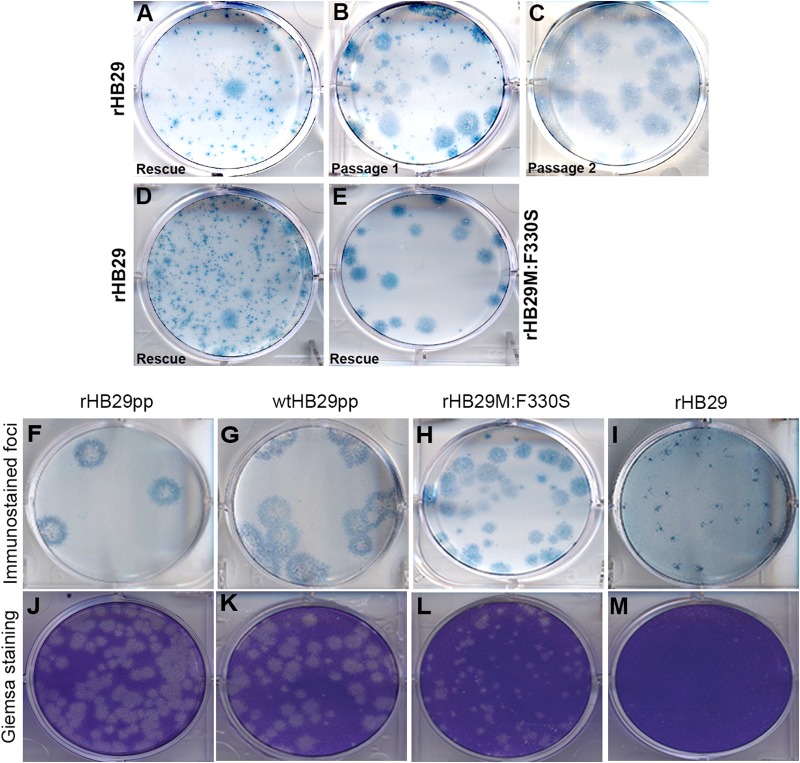

Initial attempts to generate infectious virus utilized cDNA clones based on the published sequences for the original HB29 isolate (accession numbers HM745932, HM745931, and HM745930), with the corrected S segment UTRs as described above. One microgram of each transcription plasmid (pTVT7-HB29S, pTVT7-HB29M, and pTVT7-HB29L), 0.5 μg pTM1-HB29N, and 0.1 μg pTM1-HB29L were transfected into subconfluent monolayers of BSR-T7/5 cells in a T25 flask. The supernatant was harvested at 5 days posttransfection and titrated on Vero E6 cells. An aliquot was used to infect Vero E6 cells to generate a p1 stock. This recombinant virus was designated rHB29. The average titer of virus in the supernatant of transfected cells was 6.53 × 103 focus-forming units (FFU)/ml based on 9 rescue experiments. Following one passage in Vero cells, the average titer of rescued virus reached 5.1 × 107 FFU/ml (data not shown). The foci formed by the recovered virus revealed a mixed phenotype, the predominant form being small “pinprick” foci, but larger diffuse foci were also seen (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Comparison of immunostained foci and plaque sizes of recombinant viruses. Vero E6 cells were infected with serial dilutions of virus and incubated under an 0.6% Avicel overlay for 7 days at 37°C. Cell monolayers were fixed with 4% formaldehyde. Following fixation, cell monolayers were subjected to immunofocus-staining assay or stained with Giemsa stain to visualize plaques. (A) Foci from rescue of cDNA clones representing minimally passaged HB29. (B, C) Increase in the number of large foci following passage of recombinant virus. (D, E) Direct comparison of rescue of recombinant virus from cDNA from minimally passaged HB29 (D) and from M segment cDNA containing the F330S mutation in Gn (E). (F to I) Direct comparison of immunostained foci formed by recombinant rHB29pp, authentic wtHB29pp, rHB29M:F330S, and rHB29 viruses, as indicated. (J to M) Direct comparison of Giemsa-stained plaques formed by recombinant rHB29pp, authentic wtHB29pp, rHB29M:F330S, and rHB29, as indicated.

We also successfully rescued the virus following transfection of HuH7-Lunet-T7 cells, though the titer of recovered virus (1.1 × 104 FFU/ml) was not significantly better than from BSR-T7/5 cells (data not shown).

Serial passaging selects for large-focus-forming virus.

It was noticed that after a single passage of rescued virus in Vero cells, the large-focus-forming phenotype was more abundant (Fig. 4C), and after a further passage it was the dominant form (Fig. 4D). To identify what mutation(s) had occurred in the genome of the large-focus-forming virus, total cellular RNA was extracted from Vero E6 infected with the p2 stock, and direct sequencing of viral genomic cDNAs was undertaken. Only one change between the sequence of the transfected plasmids and that of the large-focus-forming virus was detected, at nucleotide 1007 (T to C) in the M segment, resulting in a phenylalanine-to-serine change in the polyprotein at amino acid residue 330; this mutation (F330S) occurs in the mature Gn glycoprotein. The T1007C substitution was introduced into pTVT7-HB29M, and the resulting plasmid was used in the rescue system. Titration of the supernatant fluid in Vero E6 cells showed that the majority of the rescued virus, designated rHB29M:F330S, showed the large-focus phenotype (Fig. 4E). However, the average titer of rHB29:F330S generated in 3 experiments was lower than that of rHB29, at 1.35 × 102 FFU/ml (data not shown).

Rescue of cell culture-adapted plaque-forming virus HB29pp.

Full-length cDNAs to the HB29pp M and L segments were cloned into a T7 transcription plasmid, and the L ORF was cloned into a T7 expression plasmid. These plasmids, together with pTVT7-HB29S and pTM1-HB29N (since there were no differences in the S segments of HB29 and HB29pp), were transfected into BSR-T7/5 cells to generate rHB29pp. Titrations of rHB29pp, authentic HB29pp virus, rHB29, and rHB29:F330S were set up in duplicate in Vero E6 cells to allow direct comparison of both focus and plaque formation (Fig. 4F to M). One set of titrations was processed for immunostaining with the anti-HB29 N antibody, and the other set was fixed and then stained with Giemsa stain. rHB29pp gave foci with sizes similar to those of authentic HB29pp (Fig. 4F and G) and also formed similarly sized, easily discernible plaques when visualized with Giemsa staining (Fig. 4J and K). Both the foci and plaques were larger than those produced by rHB29:F330S (Fig. 4H and L). In contrast, rHB29 produced small immunostained foci and plaques were not visible (Fig. 4I and M).

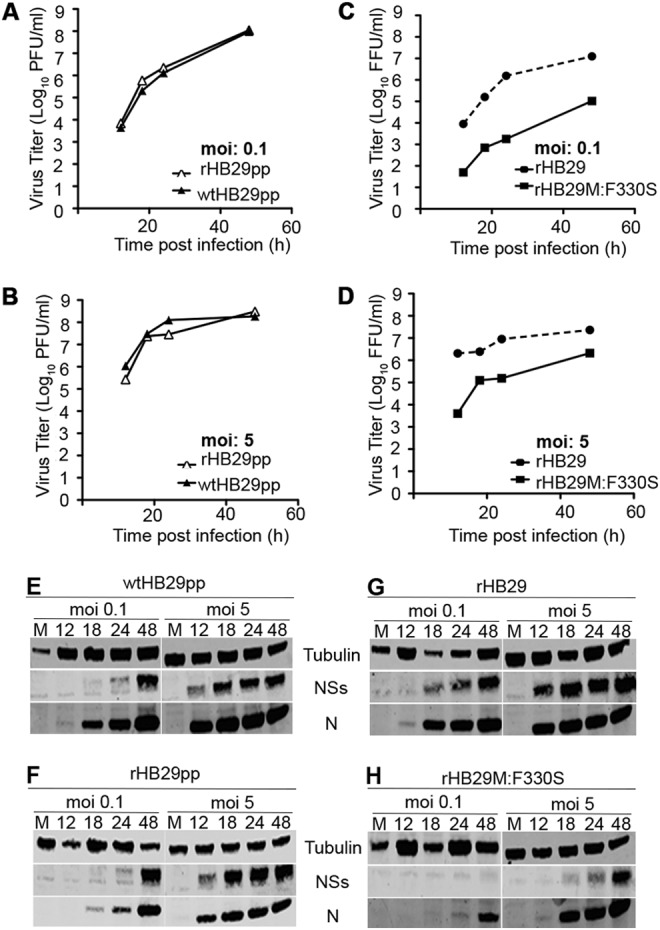

Growth properties of recombinant and wild-type viruses.

The growth properties of the different viruses were compared in Vero E6 cells at high (5) and low (0.1) MOI and titrated in the same cells by both plaque- and focus-forming assays. For HB29pp viruses, titers achieved by either assay were identical; titers of rHB29 and rHB29:F330S were recorded only by focus-forming assay. At both multiplicities, the recombinant and wild-type (i.e., authentic) HB29pp viruses grew efficiently, achieving titers of >108 PFU/ml, though the rate of growth was quicker at the higher MOI (Fig. 5A and B). The recombinant minimally passaged virus, rHB29, grew to titers approximately 10-fold lower than those of the HB29pp virus (Fig. 5C and D). The slight attenuation is presumably due to the lack of adaptation to cell culture. Interestingly, the large-focus-forming variant, rHB29:F330S, was even more attenuated, achieving titers 100- to 1,000-fold lower than those of rHB29pp, depending on the MOI (Fig. 5C and D).

FIG 5.

Growth properties of recombinant viruses. Viral growth curves were determined for Vero E6 cells infected at low (0.1) or high (5) MOI, and titers were measured by plaque assay or immunofocus assay as appropriate. (A, B) Comparison of recombinant and wild-type HB29pp. (C, D) Comparison of recombinant rHB20 and rHB29M:F330S. Graphs show a representative experiment of titrations carried out at the same time. (E to H) Western blot analysis of S-segment-encoded proteins from infected cells. Cell extracts were prepared from the growth curve samples at the time points indicated, proteins were fractionated on 4 to 12% NuPage gels, and blots were probed with anti-N, anti-NSs, and antitubulin antibodies as indicated.

Protein synthesis in infected cells.

Cell monolayers were also harvested from the samples described above for the growth curves, and lysates were prepared for Western blotting to monitor the expression of the viral N and NSs proteins (Fig. 5). Monospecific antibodies to bacterially expressed N and NSs proteins were raised in rabbits as described in Materials and Methods. In wtHB29pp-, rHB29pp-, and rHB29-infected cells, N protein was detected at 12 h p.i. in cells infected at high MOI and at 18 h p.i. following low MOI infection. At both MOI, the intensity of the N signal increased up to 48 h p.i. (Fig. 5E to G). However, the appearance of N protein was delayed in rHB29M:F330S-infected cells, with N protein not being detected until 18 h p.i. (high MOI) or 24 h p.i. (low MOI) (Fig. 5H). Expression of NSs protein appeared to be slower than that of N protein in all cases, particularly so in cells infected at low MOI. In cells infected with rHB29M:F330S at low MOI, NSs was barely detected (Fig. 5H).

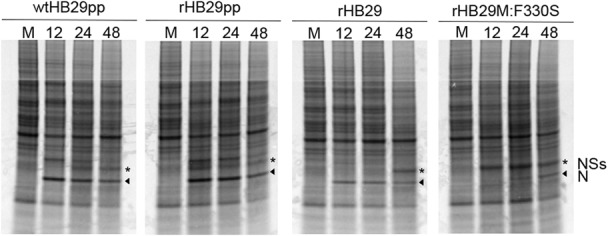

Effect of viral replication on host cell protein synthesis.

Some phleboviruses, such as RVFV, cause a global inhibition of host cell protein synthesis mediated by the NSs protein (49, 50), whereas others, such as UUKV, have little effect on cellular protein production (51). Therefore, to investigate whether SFTSV caused inhibition of host protein synthesis, Vero E6 cells were infected with wild-type or recombinant viruses at an MOI of 5, pulse labeled with [35S]methionine/cysteine at different times p.i., and cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 6). In wtHB29pp-, rHB29pp-, and rHB29-infected cells, the N protein was clearly observed identified at 12 h p.i., while in rHB29M:F330S-infected cells it was detected at 24 h p.i. (Fig. 6, black triangles). The NSs protein was less easily identified because of comigrating host proteins but was visible by 48 h p.i. in all samples (Fig. 6, asterisks). Strikingly, there was no diminution of host cell protein synthesis during the 2-h radiolabel pulse in infected cells compared to that in mock-infected cells, indicating that in this aspect SFTSV behaves like the tick-transmitted UUKV rather than the mosquito-transmitted RVFV.

FIG 6.

Lack of inhibition of host cell protein synthesis. Vero E6 cells were infected at an MOI of 5 with wtHB29pp, rHB29pp, rHB29, or rHB29M:F330S or were mock infected (M) as indicated. Cells were labeled with 30 μCi [35S]methionine and/or cysteine for 2 h at the time points indicated, and cell extracts were fractionated by SDS-PAGE. The positions of the viral N (black arrows) and NSs (asterisks) proteins are shown.

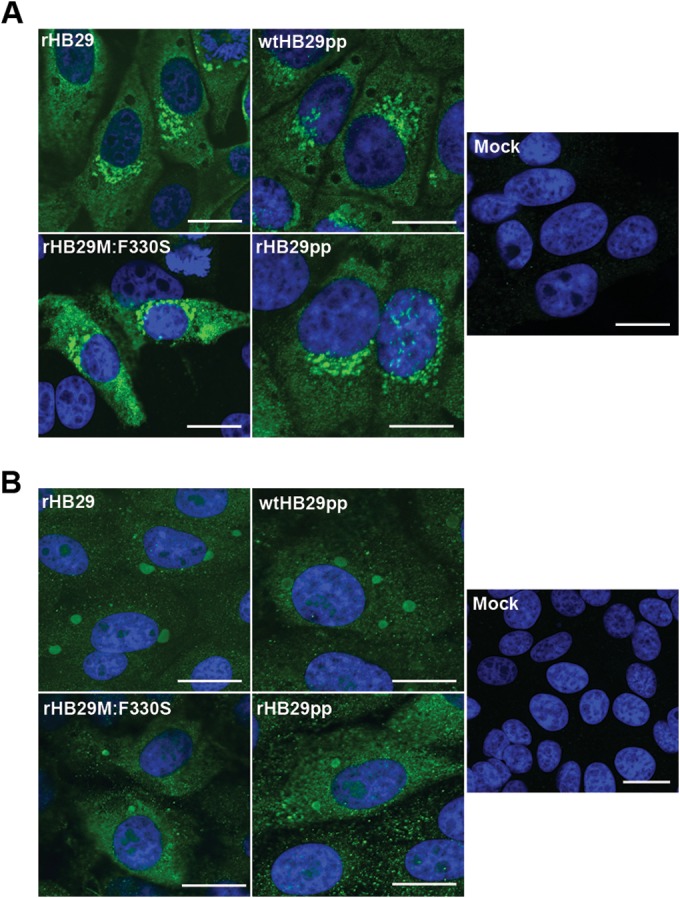

Cellular localization of S-segment-derived proteins.

Lastly, we compared the cellular localizations of both the N and NSs proteins in wild-type and in recombinant viruses. Vero E6 cells were infected at an MOI of 5, and at 24 h p.i., cell monolayers were fixed and stained with anti-N or anti-NSs antibodies for immunofluorescent imaging. The cells were counterstained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) to reveal the nuclei (Fig. 7). The N protein was detected throughout the cytoplasm of infected cells but was strongly associated with perinuclear structures that we presume represent the Golgi apparatus at this late stage of infection. There was no difference in the distribution of N protein between wild-type virus- and recombinant virus-infected cells (Fig. 7A). NSs protein also had a cytoplasmic distribution in infected cells, forming a few large, distinct, densely staining aggregates within a single cell (Fig. 7B). Again, the staining patterns of NSs were similar for wild-type HB29pp and for the recombinant viruses and in accord with published observations (45–48).

FIG 7.

Intracellular localization of N and NSs proteins in infected cells. Vero E6 cells were infected at an MOI of 5 with rHB29, wtHB29pp, rHB29pp, or rHB29M:F330S or mock infected. At 24 h p.i., the cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde, followed by staining with either anti-N (A) or anti-NSs (B) monospecific antibodies. Samples were counterstained with DAPI. Cells were examined with a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope. Bar, 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

SFTS virus is an important emerging member of the Phlebovirus genus within the Bunyaviridae. The virus emerged in rural areas of Hubei province, China, in 2009, and since that time the virus has been detected in many other areas throughout China; subsequently, isolation from patients, coupled with retrospective serological studies, has revealed the presence of the virus in Japan and South Korea as well (18–20). Here we describe the development of a reverse genetics system that allows the recovery of infectious viruses entirely from transfected cDNA clones. In particular, the recombinant version of the plaque-purified, cell culture-adapted strain HB29pp behaved similarly to the authentic virus. This is an important advance that provides a new tool with which to investigate the molecular biology of viral replication and the pathogenesis of SFTS disease.

We first generated an M-segment-based minigenome and ascertained that our nucleocapsid and polymerase protein-expressing clones were functional. We established the optimum ratio of transfected N- and L-expressing clones for maximal minigenome activity (Fig. 1), but when we then applied these to the S-segment-based minigenome, no activity was observed. This led us to reexamine the published sequence for the HB29 S segment (accession number HM745932), and 3′ RACE analysis on virion RNA revealed that there were two nucleotides missing from the published sequence, one in each of the terminal UTR sequences of the S segment (Fig. 2). Upon correction of these sequences, a significant increase in minigenome activity was seen (Fig. 2). These data indicate two points. First, SFTSV, like UUKV and RVFV (42–44), packages both types of full-length RNA into virus particles, as a 3′ RACE protocol was used on virion RNA (i.e., RNA extracted from supernatant virus) and sequences corresponding to both genomic and antigenomic RNA 3′ ends were obtained. Second, they highlight the importance of obtaining cDNA clones that exactly match the correct viral sequences in order to establish reverse genetics systems, as has recently been described for Oropouche orthobunyavirus (52).

We were able to recover recombinant viruses both from cDNA clones based on the original HB29 isolate (10) and from a cell culture-adapted plaque-forming virus designated HB29pp. Recombinant virus rescued from the original cDNA clones (rHB29) formed a mixture of very small pinprick foci and a subpopulation of larger foci when assayed by immunostaining on Vero E6 cells (Fig. 4A). Strikingly, as rHB29 was passaged on Vero E6 cells to grow working stocks, the number of larger foci increased (Fig. 4B), and by passage 2 they were the predominant form (Fig. 4C). Sequence analysis of this stock revealed only one amino acid change in the entire genome, F330S, in the glycoprotein precursor. Introducing this change back into the M segment cDNA resulted in the rescue of a virus that formed the large-focus phenotype. There are no structural data available for SFTSV glycoproteins to help understand the effect of this mutation. The larger foci suggest faster cell-to-cell spread of the virus, even though it grew to lower titers than either the authentic HB29 or HB29pp viruses. Perhaps the F330S substitution allows glycoprotein maturation and hence virion assembly to occur more rapidly, but this will require further investigation. Interestingly, this substitution appears to be unique among the numerous SFTSV glycoprotein sequences available in the database, suggesting that it does not confer any advantage to the virus in nature. In addition, this mutation was not found in the genome of the virus whose plaque was picked to generate HB29pp.

The efficiency of recovery of plasmid-derived virus was not as high as reported for other bunyaviruses, indicating perhaps that neither BSR-T7/5 nor HuH7-Lunet-T7 cells are optimally permissive for SFTSV replication. It remains to be seen whether this imposes any limitations in the ability to recover mutant viruses. However, a single passage in Vero E6 cells results in high-titer virus stocks, and perhaps in the future a rescue system based on a T7-expressing Vero E6 cell line should be considered.

A major function of bunyavirus NSs proteins, predominantly studied using BUNV and RVFV, is as the viral interferon (IFN) antagonist. For both of these viruses, some if not most of the NSs protein produced locates to the nucleus, and considerable information on the molecular mechanisms involved in inhibiting the IFN response has accrued (53). Work by several groups involving the transient expression of SFTSV NSs has elucidated a novel mechanism used by this virus to antagonize the host cell innate immune response (45–48, 54). SFTSV NSs forms distinct cytoplasmic bodies, as confirmed here (Fig. 7B); NSs was not detected in the nuclei of infected cells. The Rab5-positive cytoplasmic “viroplasm” structures cause the sequestration and spatial isolation of several key components of the cellular innate immune response, such as retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I), tripartite motif 25 (TRIM25), TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1), and interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3), thereby preventing interferon signaling (45–48, 54).

SFTSV NSs has also been shown to colocalize with N protein and to be associated with viral RNAs, suggesting that NSs plays a role in the replication of the virus (47). The NSs proteins of RVFV, BUNV, and La Crosse and Oropouche viruses have been shown to have an antagonistic effect on the activities of their respective minigenomes (37, 40, 52, 55); we therefore investigated whether SFTSV NSs behaved similarly (Fig. 3). However, transfection of an NSs-expressing plasmid did not exhibit a dramatic dose-dependent inhibition of minigenome activity, and only the largest amount of transfected plasmid (considerably larger amounts than for the other bunyavirus minigenome systems) significantly reduced activity. Interestingly, it has also been reported that SFTSV NSs viroplasm structures interact with lipid droplets and fatty acid biosynthesis inhibitors prevent their formation and hinder viral replication (47). It would be of interest to investigate this in the context of a minigenome system.

Other bunyaviruses such as RVFV and BUNV cause abrupt and complete inhibition of host cell protein synthesis during infection, which has been specifically attributed to NSs (53). In contrast, SFTSV replication appeared to have no effect on host cell protein production (Fig. 6). Both BUNV and RVFV NSs proteins have a nuclear localization, which allows for the interaction of NSs with components of the RNA polymerase II transcriptional initiation complexes that facilitate a global shutoff of host cell transcription and, later, translation of proteins. Clearly, the exclusive cytoplasmic location of SFTSV NSs does not allow interaction with the RNA polymerase II machinery.

The above observations indicate major differences between the NSs proteins of SFTSV and RVFV, two members of the Phlebovirus genus. The development of a robust reverse genetics system will allow detailed investigation of the SFTSV proteins in the context of functional viruses or deletion mutants (as opposed to studies on transiently expressed proteins), which will facilitate the study and understanding of this serious, novel, and emerging pathogen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator award to R.M.E.

REFERENCES

- 1.Plyusnin A, Beaty BJ, Elliott RM, Goldbach R, Kormelink R, Lundkvist Å, Schmaljohn CS, Tesh RB. 2012. Bunyaviridae, p 725–741 InKing AMQ, Adams MJ, Carstens EB, Lefkowits EJ (ed), Virus taxonomy: ninth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier Academic Press, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plyusnin A, Elliott RM (ed). 2011. Bunyaviridae: molecular and cellular biology. Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walter CT, Barr JN. 2011. Recent advances in the molecular and cellular biology of bunyaviruses. J Gen Virol 92:2467–2484. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.035105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elliott RM, Schmaljohn CS. 2013. Bunyaviridae, p 1244–1282 InKnipe DM, Howley PM (ed), Fields virology, 6th ed Wolters Kluwer, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouloy M. 2011. Molecular biology of phleboviruses, p 95–128 InPlyusnin A, Elliott RM (ed), Bunyaviridae: molecular and cellular biology. Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hubalek Z, Rudolf I. 2012. Tick-borne viruses in Europe. Parasitol Res 111:9–36. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-2910-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chevalier V. 2013. Relevance of Rift Valley fever to public health in the European Union. Clin Microbiol Infect 19:705–708. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikegami T, Makino S. 2011. The pathogenesis of Rift Valley fever. Viruses 3:493–519. doi: 10.3390/v3050493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikegami T. 2012. Molecular biology and genetic diversity of Rift Valley fever virus. Antiviral Res 95:293–310. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu XJ, Liang MF, Zhang SY, Liu Y, Li JD, Sun YL, DLM, Zhang QF, Popov VL, Li C, Qu J, Li Q, Zhang YP, Hai R, Wu W, Wang Q, Zhan FX, Wang XJ, Kan B, Wang SW, Wan KL, Jing HQ, Lu JX, Yin WW, Zhou H, Guan XH, Liu JF, Bi ZQ, Liu GH, Ren J, Wang H, Zhao Z, Song JD, He JR, Wan T, Zhang JS, Fu XP, Sun LN, Dong XP, Feng ZJ, Yang WZ, Hong T, Zhang Y, Walker DH, Wang Y, Li DX. 2011. Fever with thrombocytopenia associated with a novel bunyavirus in China. N Engl J Med 364:1523–1532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu S, Chai C, Wang C, Amer S, Lv H, He H, Sun J, Lin J. 2014. Systematic review of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome: virology, epidemiology, and clinical characteristics. Rev Med Virol 24:90–102. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Q, He B, Huang SY, Wei F, Zhu XQ. 2014. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, an emerging tick-borne zoonosis. Lancet Infect Dis 14:763–772. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70718-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palacios G, Savji N, Travassos da Rosa A, Guzman H, Yu X, Desai A, Rosen GE, Hutchison S, Lipkin WI, Tesh R. 2013. Characterization of the Uukuniemi virus group (Phlebovirus: Bunyaviridae): evidence for seven distinct species. J Virol 87:3187–3195. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02719-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stone R. 2010. Rival teams identify a virus behind deaths in Central China. Science 330:20–21. doi: 10.1126/science.330.6000.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu B, Liu L, Huang X, Ma H, Zhang Y, Du Y, Wang P, Tang X, Wang H, Kang K, Zhang S, Zhao G, Wu W, Yang Y, Chen H, Mu F, Chen W. 2011. Metagenomic analysis of fever, thrombocytopenia and leukopenia syndrome (FTLS) in Henan Province, China: discovery of a new bunyavirus. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002369. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y-Z, Zhou D-J, Qin X-C, Tian J-H, Xiong Y, Wang J-B, Chen X-P, Gao D-Y, He Y-W, Jin D, Sun Q, Guo W-P, Wang W, Yu B, Li J, Dai Y-A, Li W, Peng J-S, Zhang G-B, Zhang S, Chen X-M, Wang Y, Li M-H, Lu X, Ye C, de Jong MD, Xu J. 2012. The ecology, genetic diversity, and phylogeny of Huaiyangshan virus in China. J Virol 86:2864–2868. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06192-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lohmeyer KH, Pound JM, May MA, Kammlah DM, Davey RB. 2011. Distribution of Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus and Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) annulatus (Acari: Ixodidae) infestations detected in the United States along the Texas/Mexico border. J Med Entomol 48:770–774. doi: 10.1603/ME10209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim KH, Yi J, Kim G, Choi SJ, Jun KI, Kim NH, Choe PG, Kim NJ, Lee JK, Oh MD. 2013. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, South Korea, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis 19:1892–1894. doi: 10.3201/eid1911.130792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park SW, Song BG, Shin EH, Yun SM, Han MG, Park MY, Park C, Ryou J. 2014. Prevalence of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks in South Korea. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 5:975–977. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi T, Maeda K, Suzuki T, Ishido A, Shigeoka T, Tominaga T, Kamei T, Honda M, Ninomiya D, Sakai T, Senba T, Kaneyuki S, Sakaguchi S, Satoh A, Hosokawa T, Kawabe Y, Kurihara S, Izumikawa K, Kohno S, Azuma T, Suemori K, Yasukawa M, Mizutani T, Omatsu T, Katayama Y, Miyahara M, Ijuin M, Doi K, Okuda M, Umeki K, Saito T, Fukushima K, Nakajima K, Yoshikawa T, Tani H, Fukushi S, Fukuma A, Ogata M, Shimojima M, Nakajima N, Nagata N, Katano H, Fukumoto H, Sato Y, Hasegawa H, Yamagishi T, Oishi K, Kurane I, Morikawa S, Saijo M. 2014. The first identification and retrospective study of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in Japan. J Infect Dis 209:816–827. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elliott RM, Brennan B. 2014. Emerging phleboviruses. Curr Opin Virol 5:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McMullan LK, Folk SM, Kelly AJ, MacNeil A, Goldsmith CS, Metcalfe MG, Batten BC, Albarino CG, Zaki SR, Rollin PE, Nicholson WL, Nichol ST. 2012. A new phlebovirus associated with severe febrile illness in Missouri. N Engl J Med 367:834–841. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savage HM, Godsey MS Jr, Lambert A, Panella NA, Burkhalter KL, Harmon JR, Lash RR, Ashley DC, Nicholson WL. 2013. First detection of Heartland virus (Bunyaviridae: Phlebovirus) from field collected arthropods. Am J Trop Med Hyg 89:445–452. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pastula DM, Turabelidze G, Yates KF, Jones TF, Lambert AJ, Panella AJ, Kosoy OI, Velez JO, Fisher M, Staples E. 2014. Notes from the field: Heartland virus disease—United States, 2012-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 63:270–271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Punda V, Ropac D, Vesenjak-Hirjan J. 1987. Incidence of hemagglutination-inhibiting antibodies for Bhanja virus in humans along the north-west border of Yugoslavia. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg A 265:227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dilcher M, Alves MJ, Finkeisen D, Hufert F, Weidmann M. 2012. Genetic characterization of Bhanja virus and Palma virus, two tick-borne phleboviruses. Virus Genes 45:311–315. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0785-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsuno K, Weisend C, Travassos da Rosa AP, Anzick SL, Dahlstrom E, Porcella SF, Dorward DW, Yu XJ, Tesh RB, Ebihara H. 2013. Characterization of the Bhanja serogroup viruses (Bunyaviridae): a novel species of the genus Phlebovirus and its relationship with other emerging tick-borne phleboviruses. J Virol 87:3719–3728. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02845-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kokernot RH, Calisher CH, Stannard LJ, Hayes J. 1969. Arbovirus studies in the Ohio-Mississippi Basin, 1964-1967. VII. Lone Star virus, a hitherto unknown agent isolated from the tick Amblyomma americanum (Linn). Am J Trop Med Hyg 18:789–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swei A, Russell BJ, Naccache SN, Kabre B, Veeraraghavan N, Pilgard MA, Johnson BJ, Chiu CY. 2013. The genome sequence of Lone Star virus, a highly divergent bunyavirus found in the Amblyomma americanum tick. PLoS One 8:e62083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mourya DT, Yadav PD, Basu A, Shete A, Patil DY, Zawar D, Majumdar TD, Kokate P, Sarkale P, Raut CG, Jadhav SM. 2014. Malsoor virus, a novel bat phlebovirus, is closely related to severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus and heartland virus. J Virol 88:3605–3609. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02617-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J, Selleck P, Yu M, Ha W, Rootes C, Gales R, Wise T, Crameri S, Chen H, Broz I, Hyatt A, Woods R, Meehan B, McCullough S, Wang LF. 2014. Novel phlebovirus with zoonotic potential isolated from ticks, Australia. Emerg Infect Dis 20:1040–1043. doi: 10.3201/eid2006.140003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bridgen AE. 2013. Reverse genetics of RNA viruses: applications and perspectives. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buchholz UJ, Finke S, Conzelmann KK. 1999. Generation of bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) from cDNA: BRSV NS2 is not essential for virus replication in tissue culture, and the human RSV leader region acts as a functional BRSV genome promoter. J Virol 73:251–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaul A, Woerz I, Meuleman P, Leroux-Roels G, Bartenschlager R. 2007. Cell culture adaptation of hepatitis C virus and in vivo viability of an adapted variant. J Virol 81:13168–13179. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01362-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Billecocq A, Gauliard N, Le May N, Elliott RM, Flick R, Bouloy M. 2008. RNA polymerase I-mediated expression of viral RNA for the rescue of infectious virulent and avirulent Rift Valley fever viruses. Virology 378:377–384. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson KN, Zeddam JL, Ball LA. 2000. Characterization and construction of functional cDNA clones of Pariacoto virus, the first Alphanodavirus isolated outside Australasia. J Virol 74:5123–5132. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.11.5123-5132.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brennan B, Li P, Elliott RM. 2011. Generation and characterisation of a recombinant Rift Valley fever virus expressing a V5 epitope-tagged RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J Gen Virol 92:2906–2913. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.036749-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gauliard N, Billecocq A, Flick R, Bouloy M. 2006. Rift Valley fever virus noncoding regions of L, M and S segments regulate RNA synthesis. Virology 351:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Habjan M, Penski N, Wagner V, Spiegel M, Overby AK, Kochs G, Huiskonen JT, Weber F. 2009. Efficient production of Rift Valley fever virus-like particles: the antiviral protein MxA can inhibit primary transcription of bunyaviruses. Virology 385:400–408. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weber F, Dunn EF, Bridgen A, Elliott RM. 2001. The Bunyamwera virus nonstructural protein NSs inhibits viral RNA synthesis in a minireplicon system. Virology 281:67–74. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elliott RM. 2012. Bunyavirus reverse genetics and applications to studying interactions with host cells, p 200–223 InBridgen A. (ed), Reverse genetics of RNA viruses: applications and perspectives. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simons JF, Hellman U, Pettersson RF. 1990. Uukuniemi virus S RNA segment: ambisense coding strategy, packaging of complementary strands into virions, and homology to members of the genus Phlebovirus. J Virol 64:247–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ikegami T, Won S, Peters CJ, Makino S. 2005. Rift Valley fever virus NSs mRNA is transcribed from an incoming anti-viral-sense S RNA segment. J Virol 79:12106–12111. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.12106-12111.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brennan B, Welch SR, Elliott RM. 2014. The consequences of reconfiguring the ambisense S genome segment of Rift Valley fever virus on viral replication in mammalian and mosquito cells and for genome packaging. PLoS Pathog 10:e1003922. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Santiago FW, Covaleda LM, Sanchez-Aparicio MT, Silvas JA, Diaz-Vizarreta AC, Patel JR, Popov V, Yu XJ, Garcia-Sastre A, Aguilar PV. 2014. Hijacking of RIG-I signaling proteins into virus-induced cytoplasmic structures correlates with the inhibition of type I interferon responses. J Virol 88:4572–4585. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03021-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ning YJ, Wang M, Deng M, Shen S, Liu W, Cao WC, Deng F, Wang YY, Hu Z, Wang H. 2014. Viral suppression of innate immunity via spatial isolation of TBK1/IKKepsilon from mitochondrial antiviral platform. J Mol Cell Biol 6:324–337. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mju015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu X, Qi X, Liang M, Li C, Cardona CJ, Li D, Xing Z. 2014. Roles of viroplasm-like structures formed by nonstructural protein NSs in infection with severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus. FASEB J 28:2504–2516. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-243857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu X, Qi X, Qu B, Zhang Z, Liang M, Li C, Cardona CJ, Li D, Xing Z. 2014. Evasion of antiviral immunity through sequestering of TBK1/IKKepsilon/IRF3 into viral inclusion bodies. J Virol 88:3067–3076. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03510-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Habjan M, Pichlmair A, Elliott RM, Overby AK, Glatter T, Gstaiger M, Superti-Furga G, Unger H, Weber F. 2009. NSs protein of Rift Valley fever virus induces the specific degradation of the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase. J Virol 83:4365–4375. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02148-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ikegami T, Narayanan K, Won S, Kamitani W, Peters CJ, Makino S. 2009. Rift Valley fever virus NSs protein promotes post-transcriptional downregulation of protein kinase PKR and inhibits eIF2alpha phosphorylation. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000287. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pettersson RF. 1974. Effect of Uukuniemi virus infection on host cell macromolecule synthesis. Med Biol 52:90–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Acrani GO, Tilston-Lunel NL, Spiegel M, Weidmann M, Dilcher M, da Silva DEA, Nunes MRT, Elliott RM. 2014. Establishment of a minigenome system for Oropouche orthobunyavirus reveals the S genome segment to be significantly longer than previously reported. J Gen Virol doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eifan S, Schnettler E, Dietrich I, Kohl A, Blomstrom AL. 2013. Non-structural proteins of arthropod-borne bunyaviruses: roles and functions. Viruses 5:2447–2468. doi: 10.3390/v5102447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qu B, Qi X, Wu X, Liang M, Li C, Cardona CJ, Xu W, Tang F, Li Z, Wu B, Powell K, Wegner M, Li D, Xing Z. 2012. Suppression of the interferon and NF-kappaB responses by severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus. J Virol 86:8388–8401. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00612-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blakqori G, Kochs G, Haller O, Weber F. 2003. Functional L polymerase of La Crosse virus allows in vivo reconstitution of recombinant nucleocapsids. J Gen Virol 84:1207–1214. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18876-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]