ABSTRACT

Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) and transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) are economically important swine enteropathogenic coronaviruses. These two viruses belong to two distinct species of the Alphacoronavirus genus within Coronaviridae and induce similar clinical signs and pathological lesions in newborn piglets, but they are presumed to be antigenically distinct. In the present study, two-way antigenic cross-reactivity examinations between the prototype PEDV CV777 strain, three distinct U.S. PEDV strains (the original highly virulent PC22A, S indel Iowa106, and S 197del PC177), and two representative U.S. TGEV strains (Miller and Purdue) were conducted by cell culture immunofluorescent (CCIF) and viral neutralization (VN) assays. None of the pig TGEV antisera neutralized PEDV and vice versa. One-way cross-reactions were observed by CCIF between TGEV Miller hyperimmune pig antisera and all PEDV strains. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, immunoblotting using monoclonal antibodies and Escherichia coli-expressed recombinant PEDV and TGEV nucleocapsid (N) proteins, and sequence analysis suggested at least one epitope on the N-terminal region of PEDV/TGEV N protein that contributed to this cross-reactivity. Biologically, PEDV strain CV777 induced greater cell fusion in Vero cells than did U.S. PEDV strains. Consistent with the reported genetic differences, the results of CCIF and VN assays also revealed higher antigenic variation between PEDV CV777 and U.S. strains.

IMPORTANCE Evidence of antigenic cross-reactivity between porcine enteric coronaviruses, PEDV and TGEV, in CCIF assays supports the idea that these two species are evolutionarily related, but they are distinct species defined by VN assays. Identification of PEDV- or TGEV-specific antigenic regions allows the development of more specific immunoassays for each virus. Antigenic and biologic variations between the prototype and current PEDV strains could explain, at least partially, the recurrence of PEDV epidemics. Information on the conserved antigenicity among PEDV strains is important for the development of PEDV vaccines to protect swine from current highly virulent PEDV infections.

INTRODUCTION

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are spherical, enveloped RNA viruses causing enteric, respiratory, and generalized diseases in humans and animals. Mature CoV virions contain three major structural proteins, spike (S), membrane (M), and envelope (E), in their envelopes, of which the S and M proteins are glycosylated. The nucleocapsid (N) protein is the most abundant viral protein and is associated with the positive-stranded RNA genome (1). Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) and transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) cause enteritis in pigs of all ages worldwide (2, 3). Both belong to the Coronaviridae family, Coronavirinae subfamily, and Alphacoronavirus genus (4). PEDV and TGEV are mainly transmitted by the fecal-oral route. Airborne transmission of PEDV was recently confirmed experimentally in a single study (5) but not in a prior study (6). The clinical signs and pathological lesions of PEDV infection are similar to those of TGEV, making them indistinguishable (2, 7). Both viruses cause vomiting, watery diarrhea, dehydration, and decreased body weight. PEDV and TGEV enteritis results from destruction of enterocytes and villous atrophy of the intestinal mucosa, especially within the jejunum and ileum (2, 7, 8). Without adequate lactogenic immunity milk antibody protection, the mortality rate in young piglets is high, reaching 70 to 100% (7, 9). Differential diagnosis of the two viruses relies mainly on reverse transcription (RT)-PCR (10, 11) and serological assays (3, 12).

Traditionally, CoVs were classified on the basis of antigenic cross-reactivity within a group, leading to delineation of three distinct antigenic groups (1 to 3). Antigenic groups are now designated genera based on phylogenetic assays. TGEV belongs to Alphacoronavirus 1 species within the Alphacoronavirus genus, which also includes porcine respiratory coronavirus (PRCV), feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV), and canine coronavirus (CCV) (13). Dominant antigenic cross-reactions among Alphacoronavirus 1 species members have been demonstrated using various immunoassays, such as cell culture immunofluorescence (CCIF), viral neutralization (VN) assay, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and Western blotting (2, 13–15), confirming their assignment as a single species. The antigenicity of PEDV was distinct from that of the members of this established species (16), except for two reports: Zhou et al. showed a weak two-way cross-reactivity between PEDV and FIPV by Western blotting assay (17), and Have et al. reported that sera collected from a putatively CoV-infected mink cross-reacted with both PEDV and TGEV (18). Although PEDV and TGEV share similar genetic and pathogenic properties, neither the prototype of PEDV CV777 nor the other PEDV isolates showed serological cross-reactions with selected TGEV strains in some CCIF or immunohistochemistry staining assays (9, 16, 19). Recently (2013), the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses also assigned PEDV, human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E), HCoV-NL63, and 4 bat CoVs to individual separate species within the Alphacoronavirus genus (http://www.ictvonline.org/virusTaxonomy.asp).

In our and other previous studies, antigenic diversity between TGEV strains, including the cell culture-passaged virulent Miller strain at passage level 6 (M6) and attenuated Purdue strain at passage level 115 (P115), was characterized by monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) (20–22). In addition, a TGEV variant with a large deletion (227 amino acids [aa]) in the N terminus of the S protein emerged naturally in swine as a nonenteropathogenic but respiratory variant and was referred to as PRCV. The large deletion within the S protein of PRCV is also responsible for the loss of hemagglutination (HA) activity (23) and two antigenic sites (24) compared to TGEV strains. Information on the antigenic variation among PEDV strains and comparison with TGEV strains is very limited.

Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus was first observed among English feeder and fattening pigs in 1971 (25). Experimental inoculation with the Belgian isolate CV777 revealed that it is enteropathogenic for both piglets and fattening swine (8). PEDV was endemic in Europe and Asia in the last 2 decades (2, 3) until massive PED outbreaks characterized by high mortality rates in suckling piglets appeared in China in 2010 (26). North America was free of PEDV until April 2013, when a highly virulent strain of PEDV emerged suddenly in U.S. swine (9), causing significant economic losses. Full-genome-based phylogenetic analyses of the original U.S. strains revealed a close relationship with the Chinese PEDV strains AH2012 and CH/ZMDZY/11 (27, 28). Subsequently, similar highly virulent PEDV strains also caused severe outbreaks in Canada and Mexico (28), Japan (5), South Korea (29), and Taiwan (30). More recently, recombinant PEDV strains having insertions and deletions (S indel) in the N-terminal region of the S protein (S1 region) compared to the original highly virulent PEDV strains were reported in the United States. Those insertions and deletions of S indel PEDV strains are very similar to the classic PEDV strains, such as CV777 (11, 28, 31). One S indel strain (OH851) was detected from conventional pigs with asymptomatic to mild clinical signs (31). In addition, one PEDV strain having a 197-aa deletion (S 197del) in the N-terminal S protein was discovered during PEDV isolation in our laboratory (11).

The challenge of continuing highly virulent PEDV outbreaks in North America (9, 27) and Asia (5, 29, 30) necessitates the development of specific PEDV serological assays for clinical diagnosis of PEDV-exposed herds and an understanding of the antigenic relatedness of PEDV strains for vaccine development. Because PEDV and TGEV belong to the same genus of CoV, and some conserved epitopes commonly exist within CoVs, even among CoVs of distinct genera (15, 32), our aims were to examine the antigenic cross-reactivity between TGEV and PEDV and characterize the antigenic variation among different PEDV strains. Several TGEV or PEDV hyperimmune/convalescent-phase pig antisera and MAbs, as well as the homologous and heterologous TGEV (22) and PEDV (11, 27, 31) strains, were used to examine the two-way antigenic cross-reactivity by CCIF and VN tests. The one-way antibody cross-reactivity between TGEV and PEDV observed in this study was further confirmed by recombinant TGEV and PEDV N protein-based ELISA, Western blotting, and sequence analysis. The biologic and antigenic variation among different PEDV strains was evaluated by comparing the cytopathic effects (CPE) and degrees of syncytium formation in Vero cells (33), HA activities (34) and the titers of homologous and heterologous antibodies by CCIF and VN assays, respectively. Our results enhance the understanding of the antigenic diversity among PEDV strains and will aid in development of more specific serological diagnostic assays and effective vaccines to control PEDV outbreaks.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and virus strains.

African green monkey kidney (Vero) cells and swine testis (ST) cells were used for the culture of PEDV (11) and TGEV (20), respectively. Vero cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with antibiotics (100 U/ml of penicillin, 8 μg/ml of streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/ml of amphotericin B [Fungizone]) (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone, Logan, UT). ST cells were maintained in Eagle's minimal essential medium (EMEM; Life Technologies) supplemented with 1 M HEPES (Life Technologies), 5% FBS, and penicillin-streptomycin.

Three U.S. PEDV strains were isolated in Vero cells as described recently (11). Based on complete genomic sequence analysis, they differed mainly in the N terminus of the S protein. PEDV strain PC22A was genetically and pathogenically similar to the originally high virulent U.S. PEDV strains (7, 11). S indel strain Iowa106 was similar to the reported U.S. S indel PEDV strain OH851 (31). The third strain, S 197del PC177, was a novel strain most closely related to the original highly virulent U.S. PEDV strains, but with a large (197-aa) deletion in the S protein acquired upon cell culture passage (11). PC22A, S indel strain Iowa106, and S 197del strain PC177 at passage levels 9, 3, and 2, respectively, were used in this study. The PEDV prototype (CV777) strain (unknown passage level) was kindly provided by Hans Nauwynck (Ghent University, Belgium) under a U.S. Department of Agriculture permit (no. 122189). Two reference strains of TGEV, virulent Miller M6 and attenuated Purdue P115, originated from our laboratory (20, 22).

Sera and MAbs.

Convalescent-phase pig antisera to several U.S. PEDV strains were collected from gnotobiotic (Gn) pigs (PE312 and PE342) (7) or conventional pigs (PV109 and PV151) inoculated with individual PEDV strains. To obtain the hyperimmune sera against the original highly virulent U.S. PEDV strains, initial oral or intranasal inoculation and additional intramuscular boosts (PE125) or repeated oral challenges (PE276) were performed. Convalescent-phase pig PEDV (strain CV777) antisera were kindly provided by Hans Nauwynck (Ghent University). Polyclonal hyperimmune or convalescent-phase pig antisera against TGEV (strain Miller or Purdue) were produced in gnotobiotic pigs (15).

Several MAbs to the TGEV Miller N (14F10.3C, 14G9.3C, 25H7.3C, and 14E3.1) or S (48B7.3C, 25C9.3C, and 25H4.2C) protein were produced and characterized in our laboratory previously (20, 22, 24). MAbs to the N (6-29, SD17-103, and 72-111-25) or S (SD67-41) protein of a highly virulent U.S. PEDV strain (PC22A-like) were kindly provided by Steven Lawson and Eric Nelson (Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences, South Dakota State University). MAbs 3F12 and 6C8-1 against the S protein of PEDV strain DR13 was provided by Daesub Song (Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology, Daejeon, South Korea).

CCIF assay.

Confluent monolayers of Vero cells in 96-well plates were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline without Mg2+ or Ca2+ [PBS (−), Sigma, St. Louis, MO]. Subsequently, each row of a 96-well plate was inoculated with PEDV PC22A, S indel strain Iowa106, S 197del strain PC177, or CV777 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 (PC22A, S indel strain Iowa106, and S 197del strain PC177) or 0.005 (CV777) based on PFU, respectively, in DMEM supplemented with 0.3% tryptose phosphate broth and 10 μg/ml of trypsin. Confluent monolayers of ST cells in 96-well plates were inoculated with either the Miller or Purdue strain of TGEV at an MOI of 0.01 in EMEM. For negative controls, Vero and ST cells were mock inoculated with virus-free Vero or ST cell lysates. After incubation at 37°C for 24 h, monolayers were rinsed with PBS and fixed with acetone-methanol (20:80) at −20°C for 10 min. The fixed cells were used immediately for cell culture immunofluorescence (CCIF). For titration, serum samples or mouse ascites (MAb) were initially diluted 10-fold, followed by serial 4-fold dilutions. Fifty-microliter volumes of diluted samples were added to each well. The plates were incubated at room temperature for 1 h and then rinsed twice with PBS for 10 min. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-swine IgG (KPL, West Chester, PA) or goat anti-mouse IgG (Serotec, Oxford, United Kingdom) at a 1:100 or 1:500 dilution in PBS was added to each well. After 1 h of incubation in the dark, plates were rinsed twice with PBS for 5 min each time. Following addition of a drop of mounting medium (10% glycerol in PBS), plates were examined using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA). For each test, one positive Gn pig antiserum (PE125) with known PEDV PC22A-like antibody titer and one negative pig serum (PE71) obtained from a mock-inoculated Gn pig were included as positive and negative controls, respectively. All samples were tested in triplicate, and the antibody titer was expressed as the median of repeats.

PEDV FFRVN and TGEV plaque reduction virus neutralization (PRVN) assays.

The procedures for the fluorescent focus reduction virus neutralization (FFRVN) were modified from a plaque reduction assay as described previously (19) for use in 96-well microtiter plates. All sera were inactivated at 56°C for 30 min prior to testing. Serial 4-fold dilutions of the test sera or the 1:10-diluted PEDV S MAb were prepared. Subsequently, 50 μl of each dilution of a serum sample was mixed with 50 μl of a PEDV stock containing 100 (CV777) or 200 (PC22A, S indel strain Iowa106, and S 197del strain PC177) fluorescent focus units (FFU). The serum-virus mixtures were incubated for 1 h at 37°C and then inoculated onto confluent Vero cell monolayers, 50 μl/well with duplicates. After centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 30 min at room temperature to enhance virus absorption, the microtiter plates were further incubated for 4 h at 37°C. Subsequently, the inoculum was removed, cells were washed twice with PBS (−), and then 100 μl of DMEM supplemented with 10 μg/ml of trypsin was added to each well. Trypsin was added for PEDV cell entry as described previously (33, 35). After 2 h of incubation, 100 μl of DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS was added to block the action of trypsin. This procedure avoided the release of PEDV from infected cells (33, 35) and its subsequent infection of naive cells. After overnight incubation, an immunofluorescent staining was conducted as described earlier (CCIF). PEDV N MAb (6-29) at a 5,000-fold dilution and FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Serotec) were used as primary and secondary antibodies, respectively. The FFU in the wells were counted using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus). The virus neutralization antibody titer of each serum sample was expressed as the reciprocal of the dilution giving an 80% reduction in the number of FFU.

Since the culture of TGEV did not require trypsin supplements, the standard procedure for plaque reduction virus neutralization assay was conducted to titrate TGEV neutralizing antibody as described previously (22).

Production and purification of recombinant PEDV and TGEV N protein.

PEDV N gene was amplified from the PEDV strain PC22A by RT-PCR using a forward primer (5′-GCGTCGACATGGCTTCTGTCAGTTTTCA-3′) and a reverse primer (5′-CCGCTCGAGATTTCCTGTGTCGAAGATCT-3′) containing restriction enzyme sites SalI and XhoI (underlined). The PCR product was cloned into the prokaryotic expression vector pET23b (EMD Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) at corresponding restriction enzyme sites. The recombinant plasmid for full-length TGEV Miller N protein expression was generated in our previous study (15). The recombinant plasmids were separately transformed into Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) (EMD Millipore). The expression of the target proteins was then induced by addition of 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Three hours after IPTG induction, the cells were harvested and lysed by sonication. The fusion protein containing the polyhistidine tag at its C terminus was purified by affinity chromatography in Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose (Ni-NTA resin; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) under native conditions by following the manufacturer's instructions. The expressed protein was analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) with Coomassie brilliant blue R250 (Amresco, Radnor, PA) and confirmed by Western blotting with 6×His epitope tag Ab (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) and PEDV and TGEV N protein-specific MAbs.

Western blotting.

The cross-reactivity between anti-TGEV N protein MAb (14G9) and PEDV N protein was verified by Western blotting. Recombinant PEDV and TGEV proteins were denatured by boiling for 5 min in 1× loading buffer (Fermentas, Hanover, MD) in the presence of 200 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Protein concentration was measured by Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The purified recombinant proteins (2 μg/lane) were then separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Trans-Blot transfer medium; Bio-Rad). The membranes were subsequently blocked (overnight at 4°C) in blocking buffer (5% nonfat dry milk [NFDM] in PBS, pH 7.4) and incubated at room temperature for 1 h with anti-TGEV N MAb or anti-PEDV N MAb (1:1,000 dilution). The membranes were rinsed three times for 8 min each time with 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS (PBST) and then incubated with anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked antibody (KPL). The bands, after three rinses for 8 min each with PBST, were developed using the ECL Western blotting substrate (Thermo, USA), and the picture was captured with an Alpha Innotech FluorChem FC2 imager (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

ELISA using purified recombinant proteins.

Ninety-six-well MaxiSorp plates (Nunc, San Diego, CA) were coated with the purified recombinant PEDV or TGEV N proteins (50 ng/well) in coating buffer (20 mM Na2CO3, 20 mM NaHCO3, pH 9.6) at 4°C overnight. The wells were washed with 0.05% PBST and then blocked with 5% NFDM in PBS. Mouse anti-PEDV N or anti-TGEV N MAbs were serially diluted using 2% NFDM in PBS. Diluted antibodies were added to each well and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The plates were then washed with 0.05% PBST, HRP-conjugated anti-swine IgG antibody (KPL) was added, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. After the plates were washed 8 times with 0.05% PBST, 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (KPL) was added. Finally, the reaction was stopped with 0.16 M sulfuric acid, and results were read at an absorbance of 450 nm by using a SpectraMax ELISA reader (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA).

Protein sequence alignment.

The amino acid sequences of the N-terminal region of TGEV N protein, the region recognized by MAb 14G9, and the corresponding sequences of PEDV and HCoV-NL63 were aligned using the ClustalW2 program (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/). The GenBank accession numbers of these viruses are as follows: TGEV Miller, ABG89293.1; TGEV Purdue, ABG89327.1; PEDV PC22A, KM392224.1; PEDV S indel strain Iowa106, KM392232.1; PEDV S 197del strain PC177, KM392229.1; PEDV CV777, AF353511.1; and HCoV-NL63, ABE97134.1.

HA assay.

The hemagglutination (HA) assay was conducted as described previously (34), with modifications. Briefly, monolayers of Vero cells in T175 flasks were washed twice with PBS and inoculated with PEDV stocks in DMEM with 10 μg/ml of trypsin. After 2 h of incubation, the inoculum was discarded and cells were washed twice with PBS. In our preliminary experiment, treatment of PEDV with 10 μg/ml of trypsin in DMEM over 12 h reduced the viral HA titer. To avoid trypsin overdigestion and compare the HA activities among different PEDV strains, the PEDV-infected Vero cells were maintained in DMEM without trypsin supplements. At 4 postinoculation days (PID), the cell lysates were collected and clarified by centrifugation at 2,095 × g for 30 min. Virus concentration and semipurification were then performed by ultracentrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion at 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C. Semipurified PEDV was pelleted and resuspended and then either left untreated or treated with 10 μg/ml of trypsin for 10 min at 37°C. In addition, RT-quantitative PCR (11) was used to determine the PEDV RNA copy number. Afterward, serial 2-fold dilutions were incubated with an equal volume (50 μl) of rabbit red blood cells (RBCs) in PBS containing 0.2% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA). Swine, chicken, bovine, and mouse RBCs were also tested, but none showed appreciable HA titers. Trypsin-treated TGEV Miller (109 50% tissue culture infective doses [TCID50]/ml) giving 32 HA units (HAUs) and mock-inoculated Vero cell lysates were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Incubation was then performed in U-bottom microtiter plates for 30 min at 37°C. Finally, the HAU, defined as the reciprocal of the last virus dilution that completely agglutinated RBCs, was recorded. To compare the HA activities among the PEDV strains, the ratio between the HAU and RNA copy number of the PEDV genome was calculated.

RESULTS

Morphology of PEDV- and TGEV-associated CPE and antigen distribution patterns in vitro.

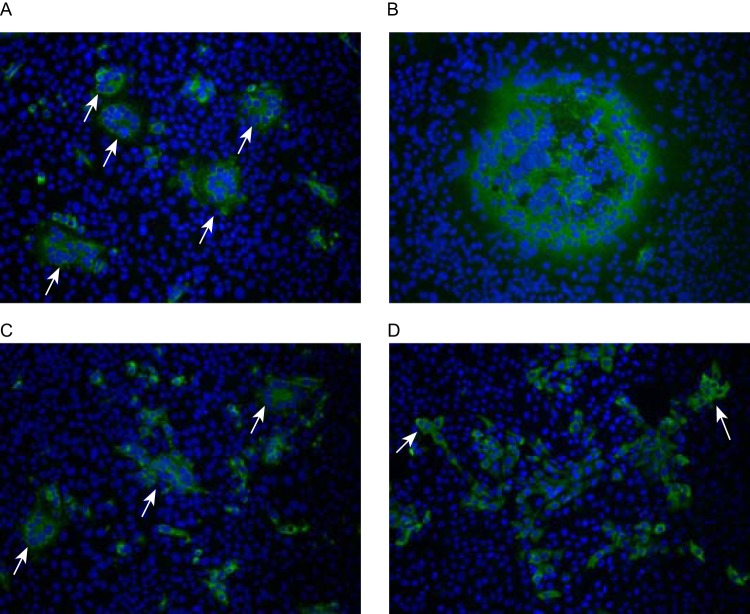

Microscopic examination revealed that PEDV-inoculated Vero cells developed distinct morphology of cytopathic effects (CPE), characterized by cell fusion, detachment, and syncytium formation (Fig. 1). No difference in morphology was observed among PEDV PC22A (Fig. 1A), S indel strain Iowa106, and S 197del strain PC177. However, PEDV CV777-infected cells (Fig. 1B) had higher cell fusion activity than U.S. PEDV strains. At the same postinoculation time, the CPE and syncytia induced by PEDV CV777 were generally larger than those induced by U.S. PEDV strains (Fig. 1A and B). For U.S. PEDV strains, about 40% of syncytia were small, containing 1 to 4 nuclei, 30% were medium size, with 5 to 8 nuclei, and 30% were large, having more than 8 nuclei. In contrast, PEDV CV777 yielded less than 5% small, 5% medium, and more than 90% large syncytia. The CCIF staining showed pinpoint or diffuse bright fluorescence signals of PEDV antigen mainly detected within the cytoplasm of the syncytia. Surrounding the fused cells, there were also fluorescent antigens of U.S. PEDV strains detected in individual cells (Fig. 1A). PEDV CV777 antigen, however, was observed in various sizes of fused cells (Fig. 1B) but rarely in individual cells.

FIG 1.

CCIF staining patterns of pig convalescent-phase PEDV PC22A-like antiserum (PE125) against PEDV PC22A-inoculated (A) and PEDV CV777-inoculated (B) Vero cell monolayers and hyperimmune anti-TGEV Miller antiserum (S409) against PEDV PC22A-infected Vero cells (C) and TGEV Miller-inoculated ST cells (D). PE125 and S409 antisera were at 160- and 40-fold dilutions in PBS, respectively. All images were taken at a 400-fold magnification. Positive signals of PEDV PC22A antigens were mainly detected as scattered pinpoints or diffuse fluorescence within the cytoplasm of syncytia and also in some individual cells near the fused cells (A), while the size of PEDV CV777-induced fused cells was larger (B). PEDV-positive cells were detected by CCIF with TGEV antiserum (S409) (C). The syncytia induced by PEDV PC22A (A and C) and fused cells induced by TGEV Miller (D) are indicated by arrows.

TGEV-inoculated ST cells also showed CPE, which was characterized by a ballooning or detachment of the cells from the cell monolayer. Cytoplasmic TGEV antigens were detected mainly by CCIF in clusters of ST cells and, less frequently, in the fused cells containing 2 to 4 nuclei (Fig. 1D). No difference in fluorescence staining pattern was observed between TGEV Miller M6- and Purdue P115-inoculated ST cells.

Assessment of antigenic cross-reaction between PEDV and TGEV and antigenic variation among PEDV strains using pig polyclonal antisera and CCIF assay.

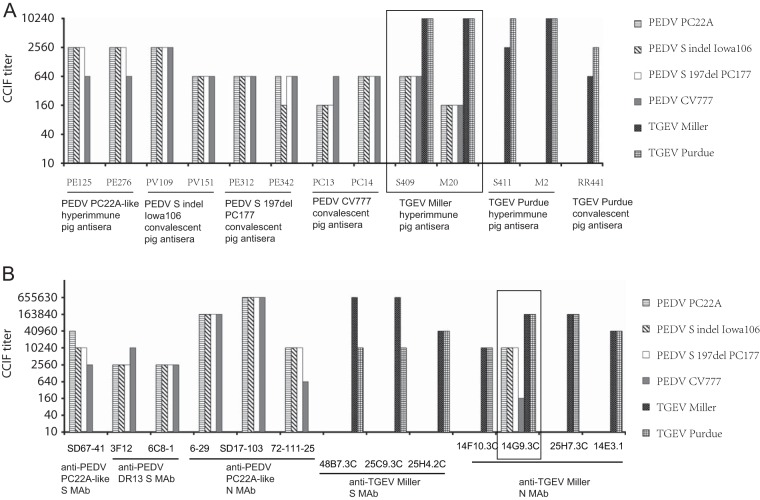

The overall CCIF antibody titers with various pig sera are summarized in Fig. 2A. All antisera reacted with the homologous strains. No fluorescence signal was detected in mock-inoculated cells.

FIG 2.

Antigenic cross-reactions as determined by CCIF among various strains of PEDV and TGEV using hyperimmune or convalescent-phase pig PEDV and TGEV antisera (A) and PEDV and TGEV S or N protein (MAbs) (B). Two hyperimmune TGEV Miller antisera (S409 and M20) and one TGEV Miller N protein MAb (14G9.3C) showed cross-reactivity with all PEDV strains (boxed).

Regarding the cross-reactivity, none of the pig PEDV hyperimmune or convalescent-phase antisera cross-reacted with TGEV. Two hyperimmune TGEV (Miller strain) antisera (S409 and M20) cross-reacted with all PEDV isolates, including PEDV PC22A (Fig. 1C), S indel strain Iowa106, S 197del strain PC177, and CV777. These pig TGEV Miller antisera (S409 and M20) reacted with TGEV Miller and Purdue strains at relatively high titers (10,240), whereas they reacted with PEDV strains at 16- to 64-fold-lower titers (Fig. 2A). Using pig hyperimmune PEDV PC22A (Fig. 1A) and TGEV Miller (Fig. 1C) antisera, no difference was observed in fluorescent staining patterns of PEDV antigen. Interestingly, the other 2 pig TGEV Purdue hyperimmune (S411 and M2) and one convalescent-phase (RR441) antiserum showed the same or slightly higher (4-fold) titers of CCIF antibody against homologous TGEV but did not cross-react with any PEDV strains (Fig. 2A).

Regarding the antigenic variation among PEDV strains, all 3 U.S. PEDV strains had the same antigenic reactivity patterns with the same panel of PEDV hyperimmune and convalescent-phase antisera (Fig. 2A). However, hyperimmune and convalescent-phase antisera against these U.S. PEDV strains showed the same or slightly higher (4-fold) titers of CCIF antibody against U.S. PEDV isolates (PC22A, S indel Iowa106, and S 197del PC177) than against the prototype PEDV CV777. Also the convalescent-phase PEDV CV777 antisera (PC13) had 4-fold-higher titers of homologous (against PEDV CV777) CCIF antibody than of heterologous (against U.S. PEDV strains) antibody (Fig. 2A).

Assessment of antigenic cross-reaction between PEDV and TGEV and antigenic variation among PEDV strains using MAbs and CCIF assay.

A panel of MAbs against PEDV and TGEV S or N protein was examined (Fig. 2B). All MAbs reacted with their homologous virus strains at high titers (>2,560). The distribution patterns of PEDV and TGEV antigen stained by MAbs were the same as those stained by polyclonal pig antisera as described above. Among four TGEV N protein MAbs, one (14G9.3C) showed cross-reactivity with all PEDV isolates tested. The titer of homologous antibody (against TGEV Miller) was 163,840, while the titers of heterologous antibody were 10,240 (U.S. PEDV strains) and 160 (PEDV CV777) (Fig. 2B). Three anti-TGEV S protein MAbs (48B7.3C, 25C9.3C, and 25H4.2C) did not cross-react with any PEDV isolates. None of the PEDV N and S protein MAbs tested cross-reacted to TGEV Miller or Purdue.

Two TGEV Miller S protein MAbs (48B7.3C and 25C9.3C) had 64-fold-higher titers of CCIF antibody and one (25H4.2C) had the same titer of CCIF antibody against homologous (Miller) and heterologous (Purdue) strains of TGEV, but all TGEV N protein MAbs induced similar fluorescence signal intensities with either TGEV Miller- or Purdue-inoculated ST cells at all dilutions. For PEDV strains, all PEDV MAbs reacted with all PEDV strains at various titers. Two PEDV PC22A N protein MAbs (6-29 and SD17-103) and one PEDV DR13 S protein MAb (6C8-l) showed similar titers against homologous and heterologous PEDV strains. One PEDV S protein IgM MAb (SD 67-41) and one PEDV N protein IgM MAb (72-11-25) had 4- to 16-fold-higher titers in CCIF assay against homologous (PC22A) than heterologous (S indel Iowa106, S 197del PC177 and CV777) PEDV strains. In addition, PEDV DR13 S protein MAb (3F12) reacted with PEDV CV777 at a 4-fold-higher titer than with U.S. PEDV strains (Fig. 2B).

Assessment of antigenic cross-reactivity between PEDV and TGEV and antigenic variations among PEDV strains by PEDV FFRVN and TGEV PRVN assays.

TGEV Miller and Purdue hyperimmune or convalescent-phase antisera neutralized the homologous virus at titers ranging from 1,024 to 16,384. However, none of them showed VN antibody against the PEDV strains (Fig. 3). Also, none of the pig PEDV hyperimmune or convalescent-phase antisera had detectable TGEV viral neutralization antibodies by PRVN assays (data not shown). Serum samples obtained from mock-inoculated Gn pigs did not neutralize PEDV or TGEV in FFRVN or PRVN assays.

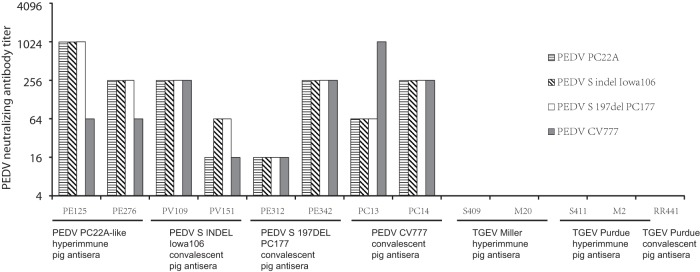

FIG 3.

Reciprocal of PEDV neutralizing antibody titers determined by fluorescent focus virus neutralization assay against four PEDV strains. The virus neutralization antibody titer of each serum sample was expressed as the dilution giving an 80% reduction in the number of fluorescent focus units.

All PEDV hyperimmune and convalescent-phase antisera had FFRVN antibody against the homologous and also heterologous PEDV strains, with the titers ranging from 16 to 1,024 (Fig. 3). Generally, the neutralizing antibody titers against three U.S. PEDV strains were similar or showed 4-fold differences. Some serum samples showed 4- to 16-fold differences in FFRVN antibody titers against PEDV CV777 and the U.S. PEDV strains. Two PEDV PC22A-like antisera (PE125 and PE276) had 4- to 16-fold-higher titers of VN antibody against homologous PC22A than against heterologous PEDV CV777. Also, one PEDV CV777 antisera (PC13) had 4-fold-higher titers of VN antibody against PEDV CV777 than against U.S. PEDV strains. In addition, none of the PEDV S or N MAbs tested in the present study showed virus neutralizing activity against PEDV or TGEV.

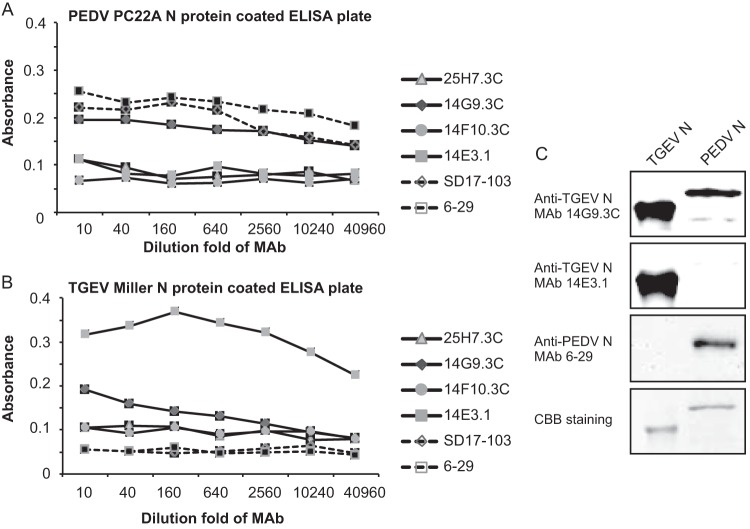

Identification of MAb cross-reactivity between PEDV and TGEV using ELISA and Western blotting and E. coli-expressed PEDV and TGEV N proteins.

Several TGEV and PEDV N protein MAbs were examined using PEDV and TGEV recombinant N protein-based ELISA (Fig. 4A and B). All MAbs reacted with the homologous antigens at titers ranging from 640 to >40,960. In agreement with the CCIF results, only TGEV MAb (14G9.3C) cross-reacted with recombinant PEDV N protein, against which the homologous and heterologous titers were the same, 40,960 (Fig. 4B).

FIG 4.

Assessment of antigenic cross-reactivity between TGEV and PEDV by ELISA (A and B) and Western blotting (C). Full-length recombinant PEDV PC22A (A) and TGEV Miller (B) N proteins were used to coat ELISA plates. PEDV N MAbs SD17-103 and 6-29 and TGEV N MAbs 14E3.1, 14F10.3C, 14G9.3C, and 25H7.3C were tested. Note that only anti-TGEV N MAb 14G9.3C cross-reacted with the recombinant N of PEDV PC22A (A and C) in one way. Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB)-stained SDS-PAGE was used as an internal control to show that loading amounts of PEDV and TGEV N proteins were comparable (C).

In Western blot assay, full-length PEDV PC22A and TGEV Miller N proteins were expressed with a six-His tag on the C terminus, yielding fusion proteins of 406 and 469 aa, which gave bands corresponding to the expected molecular masses of approximately 46 and 52 kDa, respectively. TGEV MAb (14G9.3C) reacted with both TGEV and PEDV recombinant N proteins, while PEDV N MAb (6-29) recognized the recombinant PEDV N protein only (Fig. 4C).

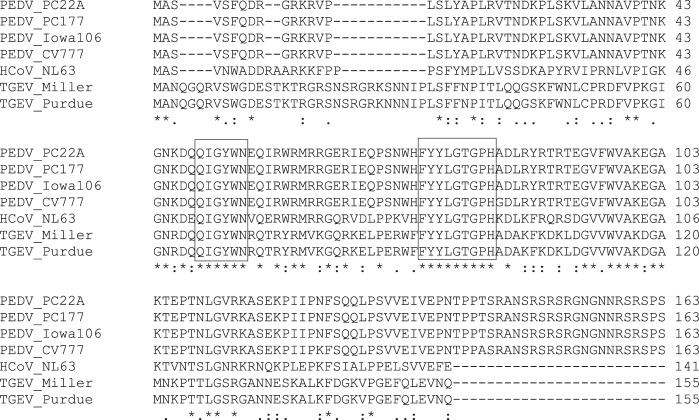

To explore the possible epitopes contributing to this cross-reaction, the amino acid sequences of full-length TGEV, PEDV, and HCoV N proteins were aligned and compared. As shown in Fig. 5 (boxes), two regions (66-QIGYWN-71 and 92-FYYLGTGPH-100) of TGEV Miller N protein were conserved among TGEV Miller and Purdue, PEDV PC22A, S indel Iowa106, S 197del PC177, CV777, and HCoV-NL63. However, the conserved region of TGEV Miller N protein (aa 92 to 100) had an additional 2 aa (101-AD-102) identical to those in U.S. PEDV strains (aa 75 to 85). In addition, one identical amino acid (alanine 84) in PEDV PC22A was replaced (glycine 84) in PEDV CV777.

FIG 5.

Multiple-sequence alignment of the N-terminal region of N protein of PEDV PC22A, PEDV CV777, TGEV Miller, TGEV Purdue, and HCoV-NL63. The conserved regions of different viruses are in the boxes. The GenBank accession numbers of the viruses are listed in the text.

Comparison of hemagglutination activities among different PEDV strains.

Without trypsin treatment, no PEDV strains tested in the present study showed HA activity. After treatment with trypsin at 37°C for 10 min, all the PEDV strains exhibited HA (Table 1). The ratios between the PEDV genomic equivalent (GE) and HA titer ranged from 5.51 to 6.13 log10 GEs per HA unit. In agreement with a previous study (23), trypsin-treated TGEV Miller and Purdue also showed HA (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of trypsin-induced HA abilities among various PEDV strainsa

| PEDV strain | No. of GEs/ml (log10)b | No. of HAUc | GE (log10)/HAU ratiod |

|---|---|---|---|

| PC22A | 8.24 | 128 | 6.13 |

| CV777 | 7.48 | 32 | 5.97 |

| Iowa106 | 7.32 | 64 | 5.51 |

| PC177 | 8.74 | 512 | 6.03 |

Mock-inoculated Vero cell lysate was used as a negative control. Trypsin-treated TGEV Miller (109 TCID50/ml) giving 32 HA units was used as a positive control. PEDV-infected Vero cells were cultured in DMEM without trypsin supplementation. Viruses collected from cell lysates were semipurified and treated with 10 μg/ml of trypsin at 37°C for 10 min.

Genomic equivalents were determined by quantitative RT-PCR.

Rabbit red blood cells were used.

The ratio was calculated as the number of GEs divided by the number of HAUs.

DISCUSSION

Porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED) resembles transmissible gastroenteritis (TGE) in pigs and is a highly contagious enteric disease of swine characterized by acute watery diarrhea, vomiting, dehydration, and weight loss (2, 3). While the impact of TGE is more limited, current outbreaks of PED in swine cause significant losses in North America (9, 27) and Asia (5, 29, 30). In the present study, the serological cross-reactivity between PEDV and TGEV was assessed by using pig antisera and MAbs. In addition, the PEDV prototype European strain CV777 and 3 genetically diverse PEDV U.S. strains (PC22A, S indel Iowa106, and S 197del PC177) isolated in our laboratory (11) were used in a CCIF assay to measure the titers of homologous and heterologous antibody against PEDV using pig antisera or MAbs. Also, an FFRVN assay was developed to measure the in vitro cross-neutralization among different PEDV strains. The results demonstrated that PEDV antigens can be detected not only using PEDV pig antiserum but also using hyperimmune TGEV Miller antiserum. Western blotting with TGEV Miller N protein MAb (14G9.3C) showed that the observed cross-reactivity was based on an N protein epitope. In addition, PEDV CV777 differed from U.S. PEDV strains in genetic, biologic, and antigenic properties. The antibody cross-reactivity between TGEV and PEDV enteropathogenic swine viruses should be considered for the development and interpretation of PEDV serological diagnostic assays. In addition, antisera raised against PEDV S indel Iowa106 and S 197del PC177 strains neutralized PC22A at a level similar to that for homologous virus. If PEDV S indel Iowa106 and S 197del PC177 are confirmed to be less virulent than PC22A, they may serve as better candidates than PEDV CV777 to develop effective vaccines to protect pigs from the current threat of the highly virulent PEDV.

Although previous studies showed no serological cross-reactions between PEDV and TGEV (9, 16, 19), the present study demonstrated that hyperimmune TGEV Miller, but not TGEV Purdue, pig antisera cross-reacted with all PEDV strains at lower CCIF antibody titers. In addition, assessment of a panel of TGEV MAbs supported at least one conserved epitope on the N protein that contributed to this cross-reactivity. The lack of cross-reactivity between PEDV and TGEV detected in previous studies (9, 16, 19) might result from several possibilities. (i) Variation of cross-reactivity can be due to different TGEV and PEDV strains tested in the different studies. Interestingly, only pigs immunized with TGEV Miller strain, and not with Purdue strain, developed serum antibodies that cross-reacted with PEDV. In addition, TGEV Miller MAb 14G9.3C reacted at higher titers to U.S. PEDV strains (10,240) than to European PEDV strain CV777 (160) (Fig. 2B). (ii) The ratio between homologous (TGEV Miller) and heterologous (U.S. PEDV strains or CV777) hyperimmune pig serum antibody titers is low. The hyperimmune pig antiserum used in our study may contain higher titers of TGEV antibody than those used in the studies of others. The relatively lower heterologous CCIF titers of antibodies in pig sera could be interpreted as background or nonspecific reactions in immunoassays, such as in ELISA. (iii) The experimental animals can influence the antibody specificities and the results. Differing from conventional pigs, Gn pigs are free from extraneous microbes and maternal or preexisting antibodies. The use of antisera from Gn pigs in the present study ensured that the antibody present in the TGEV-inoculated Gn pigs was induced only by TGEV antigen and totally free of PEDV antibodies. In fact, such disagreement in findings on cross-reactivity within the Alphacoronavirus genus and between different coronavirus genera is not unprecedented. Originally, Pensaert et al. reported no cross-reaction between PEDV CV777 and FIPV (16); however, two-way antigenic cross-reactivity between these two viruses was reported subsequently (17). In 1992, Have et al. reported a high prevalence of serum antibodies against a putative mink coronavirus (MCoV) detected in Denmark that cross-reacted with both TGEV and PEDV (18). The present study further showed that TGEV Miller can induce serum antibodies in pigs that cross-react with PEDV antigen. In agreement with phylogenetics-based classification, the antigenic cross-reactivity between TGEV Miller antisera and PEDV further supports the notion that these two viruses are related.

A highly conserved motif, FYYLGTGP, is present in the N-terminal region of the N proteins of most CoVs (32) and may mediate interspecies antigenic cross-reactivity among CoVs, even from different genera (15). Within Coronaviridae, PEDV, HCoV-229E, and HCoV-NL63 are assigned as a phylogenetically separate branch within Alphacoronavirus genus (4). PEDV N protein shared the greatest similarity to that of HCoV-229E (36). Contrary to earlier reports (9, 13, 16, 19), hyperimmune pig TGEV Miller pig antisera and TGEV Miller MAb (14G9.3C) reacted in one-way cross-reactivity assays with HCoV-NL63 as demonstrated in our previous study (15) and with PEDV in current studies, respectively. There are 3 distinct antigenic sites, N1, N2, and N3, on the TGEV N protein that are recognized by MAbs 25H7.3C, 14E3.1, and 14G9.3C, respectively (15, 20). Our more recent study on the epitope mapping of these MAbs confirmed that they target 3 distinct epitopes on the TGEV N protein: MAb 25H7.3C reacted with the epitope within the first 40 amino acids (aa), the 14E3.1 epitope was located between aa 255 and 383, and the 14G9.3C epitope spanned from aa 1 to 205 (A. N. Vlasova and L. J. Saif, unpublished data). In the present study, the results of CCIF and ELISAs showed that only anti-TGEV Miller N protein MAb (14G9.3C) cross-reacted with all PEDV strains. This finding is in agreement with the fact that only MAb 14G9.3C targets the epitope that includes the two aforementioned highly conservative motifs within TGEV and PEDV N proteins: 66-QIGYWN-71 and 92-FYYLGTGPH-100. Under the denaturing conditions of SDS-PAGE, the results of Western blotting suggested that this cross-reactivity was due to linear epitopes in the N protein. In addition, the results of the CCIF showed that the TGEV Miller MAb 14G9.3C reacted against PEDV CV777 at a lower titer (160) than against PEDV PC22A (10,240) (Fig. 2B). This may correspond to PEDV CV777 having a single amino acid (A→G at position 84) change in the second motif, resulting in lower amino acid identity than between PEDV PC22A and TGEV Miller in the conserved motif in the N protein (Fig. 5). For the serological diagnosis of PEDV, immunoassays using the whole virions as antigens are simple and widely used methods (37). Recombinant PEDV N (38) and S1 (12) protein-based ELISAs have also been developed for diagnosis. It is known that the presence of a strong immunodominant site in the N-terminal region of N protein is a common feature of the N protein from TGEV and PRCV (24) and even the betacoronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-CoV (28, 32), although no cross-reactivity between TGEV Miller MAb 14G9.3C and bovine CoV-Mebus (betacoronavirus) was revealed by CCIF (data not shown). Considering the possible TGEV, PRCV, and PEDV cross-reactivity, truncation of the antigenic site in the N-terminal region to exclude the immunodominant cross-reactive epitope of the PEDV N protein can help to improve the specificity of the immunoassays. Otherwise, the S protein of PEDV could serve as a specific antigen for immunoassay (12), assuming that the S epitopes are conserved among the relevant PEDV strains.

Interestingly, our results showed that only TGEV Miller, and not TGEV Purdue, pig antisera reacted with PEDV. However, sequence analysis did not support any potential mutation in TGEV N protein leading to this difference. In addition, this serum cross-reactivity was not totally blocked by TGEV Miller N MAb (14G9.3C) (data not shown). In fact, the hyperimmune pig antiserum contained polyclonal antibodies recognizing different TGEV Miller N epitopes. We suspect that in addition to the epitope recognized by MAb 14G9.3C, there are still other conserved cross-reactive epitopes. Some may be 3-dimensional epitopes that are not identified from sequence alignment. Further genome-wide sequence comparisons, epitope mapping studies, and structural analyses are required to identify their locations. In addition, only one-way cross-reactivity between hyperimmune TGEV Miller pig antisera and PEDV strains was observed. Two reasons were considered, as follows. (i) Only one of three distinct antigenic epitopes (15, 20) located on TGEV N harbored a conserved amino acid sequence. Only one corresponding TGEV N MAb, 14G9.3C, cross-reacted with PEDV strains. Since the first report of a U.S. PEDV in April 2013, production of U.S. PEDV MAb is still ongoing in many laboratories. A comprehensive panel of PEDV N MAbs recognizing multiple distinct antigenic epitopes is not yet available in most laboratories. Therefore, two-way antigenic cross-reactivity may be found if a PEDV N MAb recognizing the conserved amino acid sequence of the PEDV N protein is produced in the future. (ii) PEDV hyperimmune and convalescent-phase pig antisera were assumed to contain polyclonal antibodies recognizing multiple PEDV epitopes. However, no PEDV hyperimmune or convalescent-phase pig antisera cross-reacted with TGEV. Therefore, it is speculated that the PEDV N protein has different (nonconserved/non-cross-reactive) epitopes that are targets for robust immune responses compared with the TGEV N protein. Also, the conserved amino acid sequences of PEDV and TGEV N proteins may not be a major domain to elicit dominant immune responses. However, this hypothesis needs to be reexamined further.

CV777 is the historic prototype European PEDV strain (8, 17), while U.S. PEDV strains have closer genetic similarity to the strains more recently reported in China (27). When compared to U.S. strains, PEDV CV777 showed more differences in the genetic (3, 28), biologic (33), and antigenic features. Similar to the previous report that PEDV CV777 induced larger syncytia than PEDV DR13 (33), CV777 also induced larger syncytia than the three U.S. strains (Fig. 1A and B). Passage-associated cell culture adaption and growth kinetics may affect PEDV cell fusion ability. In addition, enhancement of cell fusion activity was reported to be related to one amino acid mutation, H1381R in the KxHxx motif of the cytoplasmic retrieval signal of PEDV S protein, leading to the efficient transfer of S proteins onto the cell surface (39). The sequence 884-SGRVVQKRSVIEDLLFNKV-902 in the middle of the PEDV S protein was identified as a putative fusion peptide in S protein of PEDV CV777 (33). Multiple-sequence alignments showed that there was no amino acid substitution in the KxHxx motif, but one amino acid at position 893 differed between CV777 (valine) and the U.S. strains (phenylalanine). We speculated that this amino acid substitution in the putative fusion peptide may alter the cell membrane fusion property and the syncytium size. However, this needs to be experimentally confirmed.

On the other hand, two-way antigenic and virus neutralization cross-reactivity between PEDV CV777 and the U.S. strains was observed for all of our PEDV pig antisera and MAbs, supporting the close antigenic relationships among these PEDV strains. However, some pig antisera and MAbs showed 4- to 16-fold differences between the homologous and heterologous CCIF and VN titers. It was predicted that the PEDV neutralizing epitopes were located on aa 499 to 638, 748 to 755, 764 to 771, and 1368 to 1374 of the S protein (3, 40). Comparison of PEDV PC22A and CV777 S protein sequences revealed 9 and 1 individual amino acid substitutions at the regions from aa 499 to 638 and 764 to 771, respectively. This observation suggests that some antigenic differences may exist between PEDV CV777 and the U.S. strains, perhaps in the density and/or similarity of certain epitopes expressed on the virus. Interestingly, current outbreaks of highly virulent U.S. PEDV-like strains are still causing significant economic losses in Asia (5, 29, 30), despite the availability of inactivated and attenuated PEDV vaccines, CV777 in China and DR13 in Korea, respectively (3). Therefore, U.S. PEDV isolates potentially could be better vaccine candidates than CV777 to protect swine from current PED epidemics.

Following the isolation of different U.S. PEDV strains (11), cell culture-adapted PEDV isolates not only have been used to develop immunoassays, such as CCIF and FFRVN, but also can serve as potential vaccine candidates. PEDV in the United States has emerged as at least two genetically different clades (28). However, the results of CCIF and VN tests with our panel of antisera and MAbs indicated that most antigenic determinants are still conserved for the S and N proteins. Based on the field observation, PEDV S indel strains, such as OH851 and Iowa106, were considered possible mild variants (31), but experimental pig challenge studies are required to substantiate this possibility. During PEDV isolation in our laboratory, one unique PEDV strain (S 197del PC177) that contained a large (197-aa) deletion in the S protein was generated. PRCV is a TGEV deletion variant that emerged naturally in swine. The large deletion within the N-terminal portion of the S protein of PRCV is responsible for the loss of HA activity (23). Based on the experience with the TGEV-variant PRCV strain (1, 2, 24), we speculated that the PEDV S 197del PC177 strain may lack HA activity and may be less pathogenic. However, the present study showed that PC177 still retains HA activity. This result suggests that components of the S protein responsible for HA activity could differ between PEDV and TGEV. In vivo pig studies are ongoing to evaluate the pathogenicity, immunogenicity, and cross-protection of U.S. PEDV strains, including S indel Iowa106, S 197del PC177, and high-cell-passaged PC22A.

In conclusion, the present study showed that TGEV Miller, but not Purdue, induces swine antibody cross-reactivity with PEDV. The use of MAbs showed at least one antigenic site on the N-terminal TGEV N protein that mediated this cross-reactivity. The results of CCIF and VN assays showed two-way antigenic cross-reactions among all PEDV strains tested. However, differences in antigenicity between PEDV CV777 and U.S. strains were noted in comparing the homologous and heterologous titers in CCIF and VN Ab assays. Since TGEV and PEDV cause similar clinical signs and pathological lesions in pigs (2, 3), the cross-reaction between TGEV Miller and PEDV should be considered when developing PEDV immunoassays and interpreting the results. Furthermore, the conserved antigenicity among various U.S. PEDV isolates suggests that recent isolates may potentially be better vaccine candidates than the prototype CV777 to protect U.S. swine from current PED epidemics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank H. Nauwynck (Ghent University, Belgium) for the PEDV CV777 strain and convalescent-phase pig antisera (PC13 and PC14), E. Nelson and S. Lawson (South Dakota State University) for MAbs (SD67-41, 6-29, SD17-103, and 72-111-25), and D. Song (Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology, Daejeon, South Korea) for MAbs (3F12 and 6C8-1). We thank Susan E. Sommer-Wagner and Marcia V. Lee for technical assistance.

The salary of C.-M. Lin was supported by a grant (102-2917-I-564-020) from the Ministry of Science and Technology, the Republic of China (Taiwan). Salaries and research support were provided by state and federal funds appropriated to OARDC, the Ohio State University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saif LJ. 1993. Coronavirus immunogens. Vet Microbiol 37:285–297. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(93)90030-B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saif LJ, Pensaert MB, Sestak K, Yeo SG, Jung K. 2012. Coronaviruses, p 501–524 InZimmerman JJ, Karriker LA, Ramirez A, Schwartz KJ, Stevenson GW (ed), Disease of swine, 10th ed, vol 35 John Wiley & Sons, Inc, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song D, Park B. 2012. Porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus: a comprehensive review of molecular epidemiology, diagnosis, and vaccines. Virus Genes 44:167–175. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0713-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.González JM, Gomez-Puertas P, Cavanagh D, Gorbalenya AE, Enjuanes L. 2003. A comparative sequence analysis to revise the current taxonomy of the family Coronaviridae. Arch Virol 148:2207–2235. doi: 10.1007/s00705-003-0162-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alonso C, Goede DP, Morrison RB, Davies PR, Rovira A, Marthaler DG, Torremorell M. 2014. Evidence of infectivity of airborne porcine epidemic diarrhea virus and detection of airborne viral RNA at long distances from infected herds. Vet Res 45:73. doi: 10.1186/s13567-014-0073-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowe J, Gauger P, Harmon K, Zhang J, Connor J, Yeske P, Loula T, Levis I, Dufresne L, Main R. 2014. Role of transportation in spread of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus infection, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 20:872–874. doi: 10.3201/eid2005.131628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung K, Wang Q, Scheuer KA, Lu Z, Zhang Y, Saif LJ. 2014. Pathology of US porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain PC21A in gnotobiotic pigs. Emerg Infect Dis 20:662–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Debouck P, Pensaert M. 1980. Experimental infection of pigs with a new porcine enteric coronavirus, CV 777. Am J Vet Res 41:219–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevenson GW, Hoang H, Schwartz KJ, Burrough ER, Sun D, Madson D, Cooper VL, Pillatzki A, Gauger P, Schmitt BJ, Koster LG, Killian ML, Yoon KJ. 2013. Emergence of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in the United States: clinical signs, lesions, and viral genomic sequences. J Vet Diagn Invest 25:649–654. doi: 10.1177/1040638713501675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim SY, Song DS, Park BK. 2001. Differential detection of transmissible gastroenteritis virus and porcine epidemic diarrhea virus by duplex RT-PCR. J Vet Diagn Invest 13:516–520. doi: 10.1177/104063870101300611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oka T, Saif LJ, Marthaler D, Esseili MA, Meulia T, Lin CM, Vlasova AN, Jung K, Zhang Y, Wang Q. 2014. Cell culture isolation and sequence analysis of genetically diverse US porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strains including a novel strain with a large deletion in the spike gene. Vet Microbiol 173:258–269. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerber PF, Gong Q, Huang YW, Wang C, Holtkamp D, Opriessnig T. 2014. Detection of antibodies against porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in serum and colostrum by indirect ELISA. Vet J 202:33–36. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sánchez CM, Jimenez G, Laviada MD, Correa I, Sune C, Bullido M, Gebauer F, Smerdou C, Callebaut P, Escribano JM, Enjuanes L. 1990. Antigenic homology among coronaviruses related to transmissible gastroenteritis virus. Virology 174:410–417. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90094-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horzinek MC, Lutz H, Pedersen NC. 1982. Antigenic relationships among homologous structural polypeptides of porcine, feline, and canine coronaviruses. Infect Immun 37:1148–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vlasova AN, Zhang X, Hasoksuz M, Nagesha HS, Haynes LM, Fang Y, Lu S, Saif LJ. 2007. Two-way antigenic cross-reactivity between severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and group 1 animal CoVs is mediated through an antigenic site in the N-terminal region of the SARS-CoV nucleoprotein. J Virol 81:13365–13377. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01169-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pensaert MB, Debouck P, Reynolds DJ. 1981. An immunoelectron microscopic and immunofluorescent study on the antigenic relationship between the coronavirus-like agent, CV 777, and several coronaviruses. Arch Virol 68:45–52. doi: 10.1007/BF01315166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou YL, Ederveen J, Egberink H, Pensaert M, Horzinek MC. 1988. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (CV 777) and feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV) are antigenically related. Arch Virol 102:63–71. doi: 10.1007/BF01315563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Have P, Moving V, Svansson V, Uttenthal A, Bloch B. 1992. Coronavirus infection in mink (Mustela vison). Serological evidence of infection with a coronavirus related to transmissible gastroenteritis virus and porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Vet Microbiol 31:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofmann M, Wyler R. 1989. Quantitation, biological and physicochemical properties of cell culture-adapted porcine epidemic diarrhea coronavirus (PEDV). Vet Microbiol 20:131–142. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(89)90036-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simkins RA, Saif LJ, Weilnau PA. 1989. Epitope mapping and the detection of transmissible gastroenteritis viral proteins in cell culture using biotinylated monoclonal antibodies in a fixed-cell ELISA. Arch Virol 107:179–190. doi: 10.1007/BF01317915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaughn EM, Paul PS. 1993. Antigenic and biological diversity among transmissible gastroenteritis virus isolates of swine. Vet Microbiol 36:333–347. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(93)90099-S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Welch SK, Saif LJ. 1988. Monoclonal antibodies to a virulent strain of transmissible gastroenteritis virus: comparison of reactivity with virulent and attenuated virus. Arch Virol 101:221–235. doi: 10.1007/BF01311003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schultze B, Krempl C, Ballesteros ML, Shaw L, Schauer R, Enjuanes L, Herrler G. 1996. Transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus, but not the related porcine respiratory coronavirus, has a sialic acid (N-glycolylneuraminic acid) binding activity. J Virol 70:5634–5637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simkins RA, Weilnau PA, Bias J, Saif LJ. 1992. Antigenic variation among transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) and porcine respiratory coronavirus strains detected with monoclonal antibodies to the S protein of TGEV. Am J Vet Res 53:1253–1258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wood EN. 1977. An apparently new syndrome of porcine epidemic diarrhoea. Vet Rec 100:243–244. doi: 10.1136/vr.100.12.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun RQ, Cai RJ, Chen YQ, Liang PS, Chen DK, Song CX. 2012. Outbreak of porcine epidemic diarrhea in suckling piglets, China. Emerg Infect Dis 18:161–163. doi: 10.3201/eid1801.111259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang YW, Dickerman AW, Pineyro P, Li L, Fang L, Kiehne R, Opriessnig T, Meng XJ. 2013. Origin, evolution, and genotyping of emergent porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strains in the United States. mBio 4(5):e00737–13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00737-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vlasova AN, Marthaler D, Wang Q, Culhane MR, Rossow KD, Rovira A, Collins J, Saif LJ. 2014. Distinct characteristics and complex evolution of PEDV strains, North America, May 2013–February 2014 Emerg Infect Dis doi: 10.3201/eid2010.140491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee S, Lee C. 2014. Outbreak-related porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strains similar to US strains, South Korea, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis 20:1223–1226. doi: 10.3201/eid2007.140294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin CN, Chung WB, Chang SW, Wen CC, Liu H, Chien CH, Chiou MT. 2014. US-like strain of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus outbreaks in Taiwan, 2013-2014. J Vet Med Sci 76:1297–1299. doi: 10.1292/jvms.14-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang L, Byrum B, Zhang Y. 2014. New variant of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, United States, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis 20:917–919. doi: 10.3201/eid2005.140195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He Y, Zhou Y, Wu H, Kou Z, Liu S, Jiang S. 2004. Mapping of antigenic sites on the nucleocapsid protein of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Clin Microbiol 42:5309–5314. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.11.5309-5314.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wicht O, Li W, Willems L, Meuleman TJ, Wubbolts RW, van Kuppeveld FJ, Rottier PJ, Bosch BJ. 2014. Proteolytic activation of the porcine epidemic diarrhea coronavirus spike fusion protein by trypsin in cell culture. J Virol 88:7952–7961. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00297-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park JE, Cruz DJ, Shin HJ. 2010. Trypsin-induced hemagglutination activity of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Arch Virol 155:595–599. doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0620-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shirato K, Matsuyama S, Ujike M, Taguchi F. 2011. Role of proteases in the release of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus from infected cells. J Virol 85:7872–7880. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00464-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bridgen A, Duarte M, Tobler K, Laude H, Ackermann M. 1993. Sequence determination of the nucleocapsid protein gene of the porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus confirms that this virus is a coronavirus related to human coronavirus 229E and porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus. J Gen Virol 74(Part 9):1795–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hofmann M, Wyler R. 1990. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of porcine epidemic diarrhea coronavirus antibodies in swine sera. Vet Microbiol 21:263–273. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(90)90037-V. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hou XL, Yu LY, Liu J. 2007. Development and evaluation of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay based on recombinant nucleocapsid protein for detection of porcine epidemic diarrhea (PEDV) antibodies. Vet Microbiol 123:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shirato K, Maejima M, Matsuyama S, Ujike M, Miyazaki A, Takeyama N, Ikeda H, Taguchi F. 2011. Mutation in the cytoplasmic retrieval signal of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus spike (S) protein is responsible for enhanced fusion activity. Virus Res 161:188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun DB, Feng L, Shi HY, Chen JF, Liu SW, Chen HY, Wang YF. 2007. Spike protein region (aa 636789) of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus is essential for induction of neutralizing antibodies. Acta Virol 51:149–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]