ABSTRACT

Uracil DNA glycosylases (UNG) are highly conserved proteins that preserve DNA fidelity by catalyzing the removal of mutagenic uracils. All herpesviruses encode a viral UNG (vUNG), and yet the role of the vUNG in a pathogenic course of gammaherpesvirus infection is not known. First, we demonstrated that the vUNG of murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV68) retains the enzymatic function of host UNG in an in vitro class switch recombination assay. Next, we generated a recombinant MHV68 with a stop codon in ORF46/UNG (ΔUNG) that led to loss of UNG activity in infected cells and a replication defect in primary fibroblasts. Acute replication of MHV68ΔUNG in the lungs of infected mice was reduced 100-fold and was accompanied by a substantial delay in the establishment of splenic latency. Latency was largely, yet not fully, restored by an increase in virus inoculum or by altering the route of infection. MHV68 reactivation from latent splenocytes was not altered in the absence of the vUNG. A survey of host UNG activity in cells and tissues targeted by MHV68 indicated that the lung tissue has a lower level of enzymatic UNG activity than the spleen. Taken together, these results indicate that the vUNG plays a critical role in the replication of MHV68 in tissues with limited host UNG activity and this vUNG-dependent expansion, in turn, influences the kinetics of latency establishment in distal reservoirs.

IMPORTANCE Herpesviruses establish chronic lifelong infections using a strategy of replicative expansion, dissemination to latent reservoirs, and subsequent reactivation for transmission and spread. We examined the role of the viral uracil DNA glycosylase, a protein conserved among all herpesviruses, in replication and latency of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. We report that the viral UNG of this murine pathogen retains catalytic activity and influences replication in culture. The viral UNG was impaired for productive replication in the lung. This defect in expansion at the initial site of acute replication was associated with a substantial delay of latency establishment in the spleen. The levels of host UNG were substantially lower in the lung compared to the spleen, suggesting that herpesviruses encode a viral UNG to compensate for reduced host enzyme levels in some cell types and tissues. These data suggest that intervention at the site of initial replicative expansion can delay the establishment of latency, a hallmark of chronic herpesvirus infection.

INTRODUCTION

All herpesvirus genomes encode a homolog of the host uracil DNA glycosylase. If not repaired, uracil misincorporation during DNA replication (1, 2) or conversion upon cytosine deamination (2, 3) will lead to a C:G-to-T:A transition mutation that may have severe consequences for genomic integrity (1). In the host, the recognition and removal of uracils is mediated by members of the uracil DNA glycosylase (UDG) superfamily. UNG2 is the predominant nuclear enzyme responsible for initiating repair (2–6). The role of a seemingly redundant herpesvirus UNG in viral replication is not well understood.

The viral uracil DNA glycosylases (vUNG) are typically expressed early in the viral life cycle and their expression correlates with the onset of viral DNA replication (7–10). Viral UNGs (vUNGs) interact with components of the viral DNA replication machinery, including viral DNA polymerases and lytic gene transactivators (11–13). Mutation of the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) vUNG (UL114) delays HCMV replication in cell culture (14, 15). Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA synthesis is reduced upon reactivation from latency in the absence of the vUNG (BKRF3) (13). Moreover, herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) vUNG (UL2) mediates base-excision repair in vitro (16) and loss of UL2 alone or together with loss of the HSV-1 dUTPase results in increased mutation rates upon serial passaging in culture (9). Similarly, loss of HCMV vUNG increases uracil frequency in the viral genome (15). Thus, vUNGs promote viral DNA replication and safeguard against uracil misincorporation, which is consistent with a role in maintaining the integrity of the viral genome.

The viral genes involved in nucleotide metabolism and DNA repair—the viral ribonucleotide reductase (RNR), thymidine kinase (TK), viral dUTPase, and the viral UNG (17)—are considered accessory proteins. These proteins are dispensable for viral replication in proliferating cells and yet are required in primary, quiescent, or terminally differentiated cells. Herpesviruses typically replicate within mucosal tissues at the site of infection and disseminate to distal latency reservoirs, from which the virus reactivates periodically to maintain lifelong infection. The role of a herpesvirus-encoded UNG in vivo, where the virus has to navigate both quiescent and proliferating cells, has only been described for a mouse model of HSV-1 infection. HSV-1ΔUNG was impaired in viral replication at the sites of infection and led to a reduction in virus titers in both the central and peripheral nervous system (18). Moreover, ex vivo reactivation of HSV-1 from trigeminal ganglia was defective in the absence of the vUNG (18).

The role of the gammaherpesvirus vUNG in virus replication and pathogenesis in the host is not well defined. We utilized murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV68), a natural pathogen of murid rodents, to examine the influence of the viral UNG on gammaherpesvirus infection. We constructed recombinant MHV68 viruses with a stop codon in open reading frame 46 (ORF46) and observed that loss of the vUNG reduced viral replication in fibroblasts and led to a severe impairment in viral replication within the lung. This defect in acute replication altered the kinetics of the establishment of latency in the spleen that could be largely overcome by an increase in virus dose or a change in the route of infection. Moreover, we observed a near absence of host UNG activity in the lungs that correlated with the requirement for vUNG in acute lung replication. Taken together, these data suggest that MHV68 requires the vUNG to overcome the restrictive environment of host tissues that lack adequate UNG activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and cells.

Female wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) or bred at the Stony Brook University Division of Laboratory Animal Research facility. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Stony Brook University. UNG−/− mice were obtained from the Jaenisch lab and bred at the MD Anderson Cancer Center animal facility in compliance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee policies of MD Anderson Cancer Center. Primary murine embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells were isolated from C57BL/6 mice and maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 mg of streptomycin per ml at 37°C in 5% CO2. Immortalized murine fibroblast cells (NIH 3T3 or NIH 3T12) were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 8% fetal calf serum, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 mg of streptomycin per ml at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Class switch recombination assay.

B cell isolation and the pMX retroviral infection have been previously described (19, 20). In brief, primary naive B lymphocytes from WT and UNG−/− mouse spleens were purified by negative selection with anti-CD43 beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) and cultured with 25 μg of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)/ml and 5 ng of interleukin-4 (IL-4; Sigma-Aldrich)/ml. Retrovirus for cultured B cells was produced in BOSC23 cells by cotransfection with retroviral pMX and pCL-ECO plasmids. Supernatants were harvested 2 to 3 days after transfection and used to infect purified naive B cells after 16 h of culture in LPS and IL-4. To determine relative class switching to IgG1, naive and/or retrovirally transduced primary B cells were cultured, stained with anti-mouse IgG1 antibodies (Becton Dickinson), and analyzed by flow cytometry as previously described (19, 20).

Generation of recombinant viruses.

The modified MHV68-H2bYFP genome cloned into a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) was kindly provided by the Speck laboratory (21). MHV68-H2bYFP-ORF46-stop (ΔUNG) virus was generated using en passant mutagenesis (22). Briefly, primers containing the ORF46-stop mutation (underlined), flanking WT ORF46 sequences on either side of the mutation and sequences complementary to the kanamycin selection marker (forward primer, 5′-TTTTCTACCTCAATCCTGGATAGACTACTTACAACTCTCCGCGTTTTAAATCCAAGAAGCTTGAGCAGATTATGGCTGCATAGGGATAACAGGGTAATCGATTT-3′; reverse primer, 5′-TGTTTTCTTCTGTTTTCTACTGCAGCCATAATCTGCTCAAGCTTCTTGGATTTAAAACGCGGAGAGTTGTAAGTAGTCTAGCCAGTGTTACAACCAATTAACC-3′) were used to amplify the kanamycin (Kan) selection marker from plasmid pEPKanS2 (22) by PCR (One Taq DNA polymerase; New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA). This PCR product was excised from the gel, digested with DpnI to remove input template, and transformed into freshly prepared electrocompetent Escherichia coli harboring the MHV68-H2bYFP BAC. After recovery, the bacterial cells were plated on dual chloramphenicol (34 μg/ml)-Kan (50 μg/ml) plates, followed by incubation at 30°C for 48 h. DNA was prepared from isolated colonies, and the Kan selection marker in orf46 was PCR amplified to verify the insertion of the mutagenesis cassette into the MHV68-H2bYFP BAC. Using a protocol outlined previously (20), the kanamycin selection marker was removed, leaving behind the desired ORF46 stop mutation. The orf46 gene was PCR amplified from the putative mutant BAC, digested with DraI to confirm the presence of the stop codon and then PCR products harboring the newly introduced DraI site were sequenced (Laragen, Inc., Culver City, CA). To generate marker rescued viruses, primers flanking the WT orf46 sequence were used to generate a targeting construct, which was then used to repair the ORF46-stop-disrupted virus as described above. Virus passage and titer determination were performed as previously described (23, 24).

Analysis of recombinant viral BAC DNA.

BAC DNA was prepared by Qiagen column purification. For restriction analysis, 10 μg of BAC DNA was digested overnight with DraI and then resolved in a 0.8% agarose gel in 1× Tris-acetate-EDTA. For complete genome sequencing, the BAC DNA samples were prepared for multiplex, 50-cycle, single-end read sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq2000 by the SUNY-Buffalo NextGen sequencing core. Reads were demultiplexed using the CASAVA 1.8.2 utility program. Whole-genome sequencing data were analyzed for mutations using CLC Genomics Workbench 6.0.2 (CLC bio, Aarhus, Denmark). Illumina sequence data were analyzed using CLC Genomics Workbench 6 (CLC bio/Qiagen, Aarhus, Denmark). Reads were aligned to a modified reference genome based on the WUMS Sequence (GenBank accession no. U97553), where the Kozinowski BAC sequence compiled by manual Sanger sequencing was appended to the left end. In order to spot any larger indels, contigs were generated using the CLC de novo assembler and aligned using Sequencher 5 (Gene Codes). The reference sequence was modified based on actual sequencing data. Variants from the reference sequence comprising at least 5% of reads were found by using the quality-based variant detection algorithm in CLC Genomics Workbench, using a neighborhood radius of 5, a minimum neighborhood quality score of 25, and a minimum central quality score of 29. Variants had to be present in both read directions and had to be contained in uniquely mapped reads. Importantly, engineered mutations were found in >93% of reads.

Virus growth curves.

To measure virus replication, 2 × 105 MEFs or 1.8 × 105 NIH 3T3 cells were seeded in six-well tissue culture plates 1 day prior to infection with recombinant MHV68 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 or 0.01. Triplicate wells were harvested for each time point, and the cells with the conditioned medium were stored at −80°C. Serial dilutions of cell homogenate were used to infect NIH 3T12 cells and then overlaid with 1.5% methylcellulose in DMEM supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). One week later, the methylcellulose was removed, and cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) prior to methanol fixation and staining with a 0.1% crystal violet solution in 10% methanol.

Real-time PCR.

Total cell DNA from the MHV68-infected or mock-infected MEF cells was column purified (Qiagen, Limburg, Netherlands). A total of 50 ng of DNA was input into a quantitative PCR (SYBR green low ROX mix; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) using primers specific to a region of MHV68 ORF50 (forward primer, 5′-GGCCGCAGACATTTAATGAC-3′; reverse primer, 5′-GCCTCAACTTCTCTGGATATGCC-3′) and primers for murine GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; forward primer, 5′-CCTGCACCACCAACTGCTTAG-3′; reverse primer, 5′-GTGGATGCAGGGATGATGTTC-3′). A standard curve was generated using known DNA copies of ORF50 and GAPDH plasmids, and the absolute ORF50 DNA copy number within each infection was extrapolated from the standard curve.

Antibodies and immunoblotting.

Total protein lysate was harvested in lysis buffer (150 mM sodium chloride, 1.0% IGEPAL CA-630, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 50 mM Tris [pH 8.0]) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Portions (20 μg) of each lysate were separated on a gradient 4 to 15% SDS-PAGE gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. ORF59 and ORF75C were detected using affinity-purified chicken anti-peptide antibodies against MHV68 ORF59 (25) and ORF75C (generated from the peptides PRSRSFSRHKPMKFDQS and YDAENLQCTPWQI; Gallus Immunotech, Fergus, Ontario, Canada). For ORF65 detection, a rabbit polyclonal antibody was used (kindly provided by Ren Sun, University of California at Los Angeles) (26). A rabbit polyclonal antibody to GAPDH (Sigma) was used as a loading control. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (ECL; Thermo Scientific).

Uracil DNA glycosylase activity.

HEK293T, NIH 3T12, and primary MEF cells or single cell suspensions of splenocytes or peritoneal exudate cells were harvested in HEPES-EDTA buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol) and disrupted by sonication. For lung lysates, mouse lungs were perfused with PBS, minced with scissors, and then digested with collagenase (type IV; Sigma). The protein concentration was quantified by using a Bio-Rad DC protein assay. Then, 20-μl cleavage reactions consisting of 2 μg (see Fig. 3C) or 20 μg of protein lysate (see Fig. 8) and 0.1 pmol of an Alexa 488-modified, 19-mer single-stranded DNA oligonucleotide containing a single uracil (Alexa 488-CATAAAGTGUAAAGCCTGG) were carried out at 37°C for 15 min in reaction buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl). Reactions were stopped with 20 μl of UDG stop buffer (80% formamide, 10 mM EDTA, 0.4 M NaOH, 1 mg of orange G/ml) and heated at 95°C for 15 min prior to resolution in a 7.4 M urea–15% polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA at 120 V for 1 h. Quantitation of uracil cleavage was measured by using ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare, Piscataway NJ).

FIG 3.

The vUNG of MHV68 promotes replication in primary fibroblasts. (A) Single-step growth curve in immortalized NIH 3T3 fibroblasts at an MOI of 5.0 with ΔUNG1 and ΔUNG1.MR. (B) Single-step growth curve in primary MEFs at an MOI of 5.0 with ΔUNG1 and ΔUNG1.MR. (C) Relative increase in viral DNA levels from ΔUNG1- or ΔUNG1.MR-infected MEFs at 24 hpi at an MOI of 5. Data are normalized to the 6 hpi input DNA. (D) Time course analysis of early (ORF59) and late (ORF65 and ORF75C) gene products upon a high MOI infection of MEFs. (E) Immunoblot analysis of ORF75C tegument protein levels delivered with incoming virus 1 hpi. The increase in GAPDH-normalized ORF75C levels relative to the MR virus is indicated below the gel.

FIG 8.

ORF46 is not essential for the establishment of latency upon direct intraperitoneal inoculation. C57BL/6 mice were infected at 100 PFU by the intraperitoneal route with the indicated viruses. (A) The titers of lung homogenates from mice were determined by plaque assay; the line indicates the geometric mean titer. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. The dashed line depicts the limit of detection at 50 PFU/ml of lung homogenate (log10 of 1.7). *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.005. (B) Weights of spleens harvested from the indicated infections at 18 dpi. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. (C) Frequency of splenocytes harboring latent genomes at 18 dpi. (D) Frequency of splenocytes spontaneously reactivating from latency at 18 dpi. (E) Proportion of CD95hi of CD19+ B cells in response to the indicated infection. (F) Proportion of CD95hi cells in the virus-infected YFP+ CD19+ B cell subset. *, P ≤ 0.05. (G) Weights of spleens harvested at 42 dpi. (H) Frequency of splenocytes harboring latent genomes at 42 dpi. For the limiting-dilution analyses, curve fit lines were determined by nonlinear regression analysis. The dashed lines represent 63.2%. Using Poisson distribution analysis, the intersection of the nonlinear regression curves with the dashed line was used to determine the frequency of cells that were either positive for the viral genome or reactivating virus. The data were generated from at least three independent experiments for 18 dpi and two independent experiments for 42 dpi.

Infections and organ harvests.

Eight- to ten-week-old WT mice were either infected by intranasal inoculation with 100 or 100,000 PFU of MHV68 in a 20-μl bolus or by intraperitoneal injection of 0.5 ml with 100 PFU of MHV68 under isoflurane anesthesia. The titers of inocula were determined to confirm the infectious dose. Mice were sacrificed by the application of terminal isoflurane anesthesia. For acute titers, mouse lungs or spleens were harvested in 1 ml of DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and stored at −80°C prior to disruption in a Mini-BeadBeater (BioSpec, Bartlesville, OK). Titers of the homogenates were determined by plaque assay. For latency and reactivation experiments, mouse spleens were homogenized, treated to remove red blood cells, and then filtered through a 100-μm-pore-size nylon filter. For peritoneal cells, 10 ml of medium was injected into the peritoneal cavity, and an 18-gauge needle was used to withdraw ∼7 ml of medium from each mouse. The peritoneal exudate cells were pelleted by centrifugation and then resuspended in 1 ml of DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS.

Limiting-dilution PCR detection of MHV68 genome-positive cells.

To determine the frequency of cells harboring the viral genome, single cell suspensions were prepared and used in a single-copy nested PCR. Six 3-fold serial dilutions of cells were plated in a 96-well PCR plate in a background of NIH 3T12 cells and lysed overnight at 56°C with proteinase K. The plate was subjected to an 80-cycle nested PCR with primers specific for MHV68 ORF50 (23, 24). Twelve replicates were analyzed at each serial dilution, and plasmid DNA at 0.1, 1, and 10 copies was included to verify the sensitivity of the assay.

Limiting-dilution ex vivo reactivation assay.

To determine the frequency of cells harboring latent virus capable of reactivation upon explant, single-cell suspensions were prepared from mice 16 or 18 days postinfection (dpi), resuspended in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, and plated in 12 serial 2-fold dilutions onto a monolayer of MEF cells prepared from C57BL/6 mice in 96-well tissue culture plates. Twenty-four replicates were plated per serial dilution. The wells were scored for cytopathic effect (CPE) 2 to 3 weeks after plating. To differentiate between preformed infectious virus and virus spontaneously reactivating upon cell explant, parallel samples were mechanically disrupted using a mini-bead beater prior to plating on the monolayer of MEFs to release preformed virus that is scored as CPE (23, 24).

Flow cytometry.

For the analysis of B cells, 2 × 106 splenocytes were resuspended in 200 μl of fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (PBS with 2% FBS) and then blocked with TruStain fcX (clone 93; Biolegend, San Diego, CA). The cells were subsequently washed and stained with CD19 (clone 6D5), CD95 (15A7), CD4 (GK1.5), and CD8 (53-6.7), all obtained from Biolegend. The data were collected using a Dxp8-FACScan (Cytek Development; BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo v10.0.6 (Treestar, Inc., Ashland, OR).

Statistical analyses.

The data were analyzed by using Prism 5 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Statistical significance was determined using either an analysis of variance test, followed by a Bonferroni correction, or an unpaired two-tailed t test. Under Poisson distribution analysis, the frequencies of latency establishment and reactivation from latency were determined by the intersection of nonlinear regression curves with the line at 63.2.

RESULTS

The viral UNG of murine gammaherpesvirus 68 rescues class switch recombination in B cells lacking UNG.

UNG recognizes and cleaves the N-glycosidic bond of uracils to generate an abasic site that is subsequently incised by host endonucleases prior to repair by the base-excision repair pathway (27). In addition, host UNG2 excises uracils from activation-induced deaminase (AID) induced U:G lesions within the immunoglobulin locus to facilitate somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination, two functions essential for generating antibody diversity (6, 28). To determine whether the vUNG exhibits uracil excision activity and if disruption of this gene impairs this activity, we tested the ability of the vUNG to rescue immunoglobulin class switch recombination in UNG-null B cells. Naive resting B cells were purified from the spleens of WT and UNG−/− mice and stimulated with IL-4 and LPS to induce class switch recombination (CSR). CSR was monitored by flow cytometry with antibodies to IgG1. UNG−/− cells were unable to switch to IgG1, while WT cells exhibited an approximate 20% shift to IgG1 upon stimulation (Fig. 1A). To test complementation, we transduced UNG−/− cells with a retrovirus expressing host UNG or the WT MHV68 vUNG together with green fluorescent protein (GFP) to mark UNG-expressing B cells (Fig. 1B). Transduction of WT MHV68 vUNG or host UNG2 resulted in restoration of CSR to the UNG−/− cells, an equivalent proportion of cells became GFP+/IgG1+ (9.0 and 8.4%, respectively) (Fig. 1C). In contrast, transduction with a retrovirus encoding a vUNG that harbors a premature stop codon (vUNG.stop) did not rescue CSR in UNG−/− cells (Fig. 1C). These results demonstrate that the vUNG encoded by MHV68 exhibits uracil glycosylase activity and that a premature stop codon in the MHV68 vUNG abrogates this catalytic function.

FIG 1.

MHV68 UNG complements UNG−/− B lymphocytes for class switch recombination (CSR). (A) Representative flow cytometry plot demonstrating that WT, but not UNG−/− B cells undergo CSR to IgG1. (B) Schematic of CSR assay. Primary B cells from the indicated naive mice are treated with LPS and IL-4 for 4 days. (C) Representative flow cytometry plot of CSR to IgG1 in UNG−/− splenocytes transduced with empty vector or pMX expressing murine UNG2, MHV68 vUNG, or MHV68 vUNG.stop. The percentage of infected (GFP+) cells expressing IgG1 is indicated on the plot. (D) Summary graph of percentage of GFP+ cells that underwent CSR to IgG1 4 days after retroviral infection. Bars represent the means ± the standard deviations (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.005). UNG complementation data are representative of three independent experiments.

Uracil DNA glycosylase promotes gammaherpesvirus replication in primary fibroblasts.

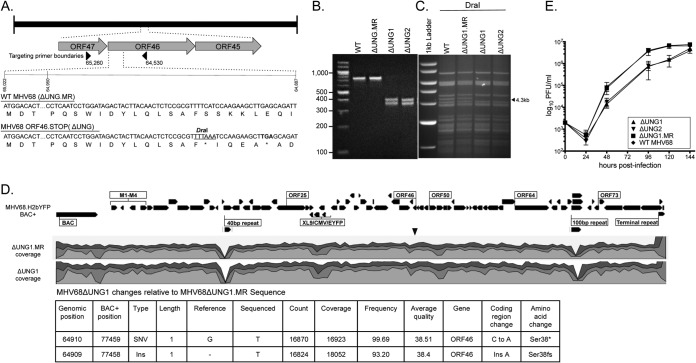

To examine the function of the vUNG in MHV68 pathogenesis, we generated a recombinant MHV68 encoding the premature ORF46-stop codon utilized in the CSR assay. The ORF46-stop virus, here termed ΔUNG, was generated from the MHV68-H2bYFP marking virus using allelic exchange (22, 29). The cytosine at nucleotide (nt) position 114 was replaced with two adenines. This insertion introduced a TAA stop codon and a unique DraI site (underlined) (Fig. 2A). ΔUNG1 was repaired back to the WT sequence and is termed ΔUNG1.MR (marker rescue). The presence of the UNG mutation was confirmed by DraI digestion of the ORF46 gene (Fig. 2B) and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis (Fig. 2C). The lack of additional mutations in the MR and mutant viruses was confirmed by whole-genome sequencing (Fig. 2D). ΔUNG1 and ΔUNG2 refer to mutant viruses derived from two independent BAC clones.

FIG 2.

Construction and characterization of a recombinant MHV68ΔUNG virus. (A) Schematic of the ΔUNG virus. WT and mutant ORF46 nucleotide sequences are compared, highlighting the presence of the unique DraI site and insertion of the TAA stop codon in ΔUNG (underlined). Underneath the nucleotide sequence is the translated amino acid sequence. An asterisk (*) indicates the presence of the stop codon. Arrows indicate the boundaries of primers to generate a 725-bp amplimer to verify the mutation. (B) DraI digestion of a 725-bp amplimer to confirm the unique DraI site in the two independent ORF46.STOP viruses (ΔUNG1 and ΔUNG2), but not the marker rescue of ΔUNG1 (ΔUNG1.MR) or wild-type (WT) MHV68. (C) Confirmation of mutant and repaired MHV68 viruses by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. Portions (10 μg) of WT BAC DNA, ΔUNG1.MR, ΔUNG1, or ΔUNG2 were digested with DraI and resolved on a 0.8% agarose gel. An arrowhead indicates the loss of a 4.3-kb fragment with the insertion of the unique DraI site into ORF46. (D) Analysis of MHV68 BAC by whole-genome sequencing. (Top) Illumina reads were aligned to the MHV68.H2bYFP BAC genome. Shown in the histogram are levels of coverage across the genome; the scale is 0 to ×30,000, 56 million total mapped reads for ΔUNG1, and 39 million reads for ΔUNG1.MR. Variants are indicated by inverted triangles. The two regions of low coverage are due to the paucity of uniquely mapped reads in the small repeat regions. (Bottom) Table of expected variants in the UNG.STOP BAC not found in UNG.MR. (E) Multistep growth curve in primary MEF cells at an MOI of 0.01 with the indicated viruses.

In multistep growth curves, we observed a lag in virus replication with loss of the vUNG. ΔUNG1 and ΔUNG2 replication lagged behind WT and ΔUNG1.MR between 24 and 120 h postinfection (hpi) before reaching similar peak titers at 148 hpi (Fig. 2E). We next compared replication in immortalized fibroblasts (NIH 3T3) or primary MEFs after infection at an MOI of 5. In these single-step growth curves, loss of the vUNG resulted in a 2.5-fold replication defect in immortalized NIH 3T3 cells (Fig. 3A) and a significant 8-fold defect in primary MEFs (Fig. 3B). Viral DNA synthesis between 6 and 24 hpi (Fig. 3C) and viral transcripts from different kinetic classes were not impacted by the loss of the vUNG (data not shown). An immunoblot analysis of viral proteins representative of early and late gene classes did not reveal significant defects in gene expression during infection of the MEFs (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, we observed an increase in the levels of ORF75C tegument protein delivered to cells newly infected with viruses lacking vUNG compared to UNG.MR (Fig. 3E). We examined the particle to PFU ratio by quantitating the encapsidated viral genomes and PFU from a concentrated stock prepared in parallel for ΔUNG1 and ΔUNG1.MR. The ΔUNG1 virus had a 6-fold increase in the particle/PFU ratio compared to the repaired ΔUNG1.MR (data not shown). Based on these findings taken together, we propose that the vUNG promotes an aspect of virus replication distinct from DNA synthesis or selected early and late gene product expression, likely impacting assembly or infectivity of the virions.

The vUNG of MHV68 retains enzymatic UNG activity in infected primary fibroblasts.

We next examined UNG activity in MEFs infected with MHV68. Protein lysates harvested from primary MEFs at 24 hpi were incubated with a 19-mer single-stranded oligonucleotide containing a single uracil. Uracil excision, followed by alkaline treatment of the abasic site, generates a 9-mer product that is resolved by denaturing PAGE (Fig. 4A). Lysates from WT- or MR-infected MEFs cleaved ca. 50% of the uracil-containing oligonucleotide at 24 hpi (Fig. 4B). In contrast, there was no significant difference in oligonucleotide cleavage between ΔUNG1-infected and uninfected MEFs over an extended time course (Fig. 4C). These data indicate that the vUNG drives the enzymatic UNG activity that is detected in the infected MEFs.

FIG 4.

The vUNG of MHV68 retains enzymatic UNG activity in infected primary fibroblasts. (A) Schematic of UNGase assay using an Alexa 488-labeled oligonucleotide containing a single uracil. Uracil excision leads to oligonucleotide cleavage. (B) Denaturing polyacrylamide gel analysis of oligonucleotide cleavage upon incubation with lysates prepared from MEFs uninfected or infected with WT, ΔUNG1.MR, and ΔUNG1 at 24 hpi. (C) Time course analysis of UNG activity within primary MEFs infected with WT or ΔUNG1 viruses. The percentage of cleavage relative to the negative control is indicated below each gel.

Loss of the MHV68 UNG reduces acute viral replication in the lungs and the establishment of latency in mice.

To assess the role of the vUNG in replication within an infected animal, we examined acute replication in the lungs after an intranasal infection of C57BL/6 mice. ΔUNG1 and ΔUNG2 exhibited reduced replication in the lung compared to ΔUNG1.MR, with undetectable virus titers in 9 of 10 mice at 4 dpi. ΔUNG1.MR titers increased by 20-fold at 7 dpi and were comparable to WT-infected mice. At 9 dpi, we observed a further 2.5-fold increase in ΔUNG1.MR titers, with complete clearance from the lungs by 12 dpi. In contrast, virus replication in the lungs of mice infected with ΔUNG viruses failed to reach the levels of WT and UNG.MR replication, with an ∼2-log defect in virus titers at 9 dpi. Virus was not detected in the lungs of ΔUNG infected mice at 12 dpi, indicating that there was no delay in clearance with loss of the vUNG (Fig. 5). Thus, the vUNG promotes acute replication of MHV68 in the lung.

FIG 5.

The vUNG of MHV68 is critical for replication in the lungs of infected mice. C57BL/6 mice were infected at 100 PFU by the intranasal route with two independent viruses encoding stop codon disruptions in ORF46 (ΔUNG1 and ΔUNG2) and the marker rescue virus of ΔUNG1 (ΔUNG1.MR). The titers of lung homogenates from mice were determined by plaque assay; the line indicates the geometric mean titer. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. The dashed line depicts the limit of detection at 50 PFU/ml of lung homogenate (log10 of 1.7). *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.005.

Within 2 weeks of intranasal infection, virus replication in the lung is resolved and the virus transits to the spleen where it targets B lymphocytes. The peak in splenic latency occurs between 14 and 18 dpi and coincides with splenomegaly. Mice infected with ΔUNG1.MR exhibited splenomegaly with a 2-fold increase in splenic weight at 16 dpi, while mice infected with ΔUNG viruses did not exhibit significant splenomegaly (Fig. 6A). This defect in splenomegaly correlated with a two-log reduction in the frequency of splenocytes that harbor the viral genome in mice infected with the ΔUNG viruses compared to ΔUNG1.MR (Fig. 6B, summarized in Table 1). This impairment in latency establishment was accompanied by a similar reduction in the frequency of reactivation from latency upon explant (Fig. 6C, summarized in Table 2). The severity of the defect in the establishment of latency precluded a determination of whether vUNG plays a role in splenic reactivation. In spite of a severe latency defect at 16 dpi, the frequency of genome-positive splenocytes 6 weeks after infection with ΔUNG1 was nearly equivalent to ΔUNG1.MR (Fig. 6D). Thus, loss of vUNG delays latency establishment in the spleen after intranasal inoculation of mice.

FIG 6.

MHV68 vUNG is essential for the establishment of latency in the spleen at early, but not late times during chronic infection after low-dose intranasal inoculation. C57BL/6 mice were infected at 100 PFU by the intranasal route with the indicated viruses. (A) Weights of spleens harvested 16 dpi (***, P ≤ 0.001). (B) Frequency of splenocytes harboring latent genomes at 16 dpi. (C) Frequency of splenocytes undergoing reactivation from latency upon explant. (D) Frequency of splenocytes harboring latent genomes at 6 weeks postinfection. For the limiting-dilution analyses, curve fit lines were determined by nonlinear regression analysis. Using Poisson distribution analysis, the intersection of the nonlinear regression curves with the dashed line at 63.2% was used to determine the frequency of cells that were either positive for the viral genome or reactivating virus. The data were generated from at least three independent experiments for 16 dpi and from two independent experiments for 42 dpi.

TABLE 1.

Frequencies of cell populations harboring viral genomes in C57BL/6 mice

| Virus, dose (PFU), and route of infectiona | Organb | dpi | Frequency of viral genome-positive cellsc | No. of cells |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-positive cellsd | Total | ||||

| ΔUNG.MR, 100, i.n. | Spleen | 16 | 1/469f | 238,805 | 1.1 × 108 |

| Spleen | 42 | 1/14,933 | 3,147 | 4.7 × 107 | |

| ΔUNG.1, 100, i.n. | Spleen | 16 | 1/67,652 | 1,281 | 8.7 × 107 |

| Spleen | 42 | 1/7,544 | 4,699 | 3.5 × 107 | |

| ΔUNG.2, 100, i.n. | Spleen | 16 | 1/<100,000 | <570 | 5.7 × 107 |

| ΔUNG.MR, 100,000, i.n. | Spleen | 16 | 1/267 | 347,293 | 9.3 × 107 |

| ΔUNG.1, 100,000, i.n. | Spleen | 16 | 1/977 | 81,883 | 8.0 × 107 |

| ΔUNG.MR, 100, i.p. | Spleen | 18 | 1/99 | 602,453 | 6.0 × 107 |

| Spleen | 42 | 1/8,397 | 4,498 | 3.8 × 107 | |

| PEC | 18 | 1/196 | 30,148 | 5.9 × 106 | |

| PEC | 42 | 1/963 | 2,307 | 2.2 × 106 | |

| ΔUNG.1, 100, i.p. | Spleen | 18 | 1/327 | 198,776 | 6.5 × 107 |

| Spleen | 42 | 1/20,167 | 2,093 | 4.2 × 107 | |

| PEC | 18 | 1/467 | 7,448 | 3.5 × 106 | |

| PEC | 42 | 1/647 | 3,434 | 2.2 × 106 | |

Infection was performed with either MHV68ΔUNG (MHV68 lacking viral UNG) or MHV68ΔUNG.MR (repaired UNG mutant virus). i.n., intranasal; i.p., intraperitoneal.

That is, the organ harvested for limiting-dilution analysis.

Frequency values were determined from the means of at least three independent experiments. Organs were pooled from three to five mice per experiment. Values statistically different in the frequency of viral genome-positive cells from ΔUNG-infected mice compared to ΔUNG.MR infections are indicated in boldface.

That is, the mean number of genome-positive cells per infected mouse.

TABLE 2.

Frequencies of cells reactivating MHV68 in C57BL/6 mice

| Virus, dose (PFU), and route of infectiona | Organb | dpi | Frequency of reactivating cellsc | No. of cells |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cells reactivating latent virusd | Total | ||||

| ΔUNG.MR, 100, i.n. | Spleen | 16 | 7,490 | 14,953 | 1.1 × 108 |

| Spleen | 42 | ND | ND | 4.7 × 107 | |

| ΔUNG.1, 100, i.n. | Spleen | 16 | <100,000 | <866 | 8.7 × 107 |

| Spleen | 42 | ND | ND | 3.5 × 107 | |

| ΔUNG.2, 100, i.n. | Spleen | 16 | <100,000 | <570 | 5.7 × 107 |

| ΔUNG.MR, 100,000, i.n. | Spleen | 16 | 5,250 | 17,662 | 9.3 × 107 |

| ΔUNG.1, 100,000, i.n. | Spleen | 16 | 31,335 | 2,553 | 8.0 × 107 |

| ΔUNG.MR, 100, i.p. | Spleen | 18 | 15,561 | 3,832 | 6.0 × 107 |

| Spleen | 42 | ND | ND | 3.8 × 107 | |

| PEC | 18 | 1,677 | 3,523 | 5.9 × 106 | |

| PEC | 42 | ND | ND | 2.2 × 106 | |

| ΔUNG.1, 100, i.p. | Spleen | 18 | 12,885 | 5,044 | 6.5 × 107 |

| Spleen | 42 | ND | ND | 4.2 × 107 | |

| PEC | 18 | 5,086 | 683 | 3.5 × 106 | |

| PEC | 42 | ND | ND | 2.2 × 106 | |

Infection was performed with either MHV68ΔUNG (MHV68 lacking viral UNG) or MHV68ΔUNG.MR (repaired UNG mutant virus). i.n., intranasal; i.p., intraperitoneal.

That is, the organ harvested for limiting-dilution analysis.

Frequency values were determined from the means of at least three independent experiments. Organs were pooled from three to five mice per experiment. Values statistically different in the frequency of viral genome-positive cells from ΔUNG-infected mice compared to ΔUNG.MR infections are indicated in boldface.

That is, the mean number of genome-positive cells per infected mouse. ND, not determined.

An increase in dose partially rescues the latency defect of the virus lacking UNG.

Since the intranasal inoculation of mice with 100 PFU of virus identified defects in both acute replication in the lung, as well as the establishment of splenic latency in ΔUNG-infected animals, we reasoned that the delay in splenic latency might solely be attributed to a failure of the UNG-null viruses to expand in the lung. To test this hypothesis, we increased the virus inoculum by 3 orders of magnitude to 100,000 PFU. Mean lung titers from mice infected with 100,000 PFU (Fig. 7A) were increased overall compared to lung titers from mice infected with 100 PFU (Fig. 5). Acute replication in the lungs of mice infected with ΔUNG1 was partially restored, but still reduced by 6- and 10-fold compared to ΔUNG1.MR-infected mice at 4 and 9 dpi, respectively (Fig. 7A). Coupled with this partial rescue of replication in the lung, splenomegaly was restored in ΔUNG1-infected animals at 16 dpi (Fig. 7B). Moreover, spleens from mice infected with ΔUNG1 exhibited a slight, but statistically insignificant, 4-fold reduction in the frequency of genome positive cells (Fig. 7C, summarized in Table 1). Reactivation from latency was only slightly reduced in mice infected with ΔUNG1 relative to ΔUNG1.MR (Fig. 7D, summarized in Table 2). In summary, an increase in virus dose was able to partially overcome a deficit in replication in the lung and led to near complete restoration of latency in the spleen. Thus, a large portion of the splenic defect in latency and reactivation observed with a low dose of ΔUNG viruses stems from a requirement for the vUNG to drive MHV68 replication in the lung and subsequent dissemination from the lung to the spleen.

FIG 7.

Infection with a higher dose partially overcomes the loss of vUNG. C57BL/6 mice were infected at 100,000 PFU by the intranasal route with the indicated viruses. (A) The titers of lung homogenates from mice were determined by plaque assay; the line indicates the geometric mean titer. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. The dashed line depicts the limit of detection at 50 PFU/ml of lung homogenate or a log10 of 1.7. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.005. (B) Weights of spleens harvested from the indicated infections 16 dpi. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.005. (C) Frequency of splenocytes harboring latent genomes. (D) Frequency of splenocytes undergoing reactivation from latency upon explant. For the limiting-dilution analyses, curve fit lines were determined by nonlinear regression analysis. Using Poisson distribution analysis, the intersection of the nonlinear regression curves with the dashed line at 63.2% was used to determine the frequency of cells that were either positive for the viral genome or reactivating virus. The data were generated from at least three independent experiments.

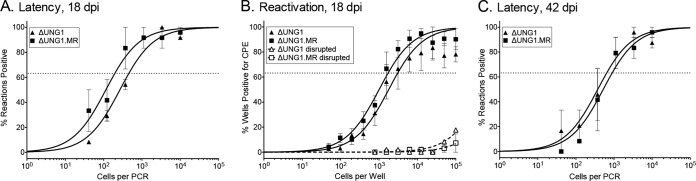

Bypassing the lung via intraperitoneal inoculation rescues the splenic latency defect of murine gammaherpesvirus lacking UNG.

The intranasal route of infection identified a critical role for the vUNG in seeding the spleen that was partially overcome with an increase in virus dose. We next bypassed lung replication using direct administration of virus by intraperitoneal inoculation. In general, acute splenic titers were lower than those in the lungs, with mean peak titers at 9 dpi of ∼50 and ∼150 PFU/ml for ΔUNG1 and ΔUNG1.MR, respectively (Fig. 8A). No significant difference in splenomegaly was observed between ΔUNG1- and ΔUNG1.MR-infected animals (Fig. 8B). Loss of the vUNG resulted in a slight 3-fold decrease in the frequency of genome positive splenocytes at 18 dpi (Fig. 8C, summarized in Table 1). The frequency of reactivation from latency at this early time point was not impacted by the loss of the vUNG (Fig. 8D, summarized in Table 2). We tracked the splenic cells harboring MHV68 using the yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) reporter (21) and found that ΔUNG1 and ΔUNG1.MR colonized CD95hi CD19+ B cells with equivalent frequencies (Fig. 8E and F). At 6 weeks postinfection, there was no difference in either spleen weights (Fig. 8G) or the frequency of genome positive splenocytes (Fig. 8H). These experiments using direct intraperitoneal infection demonstrate that the loss of the vUNG does not have a significant impact on latency in the splenic reservoir between 18 and 42 dpi.

The viral UNG is dispensable for latency in peritoneal exudate cells.

In addition to the major latent reservoir, B lymphocytes, MHV68 latency is also established in macrophages and dendritic cells (30, 31). We examined whether the vUNG plays a role in latency establishment in peritoneal exudate cells (PECs), which are comprised largely of macrophages. Loss of the vUNG did not influence the frequency of genome positive cells at either 18 or 42 dpi after intraperitoneal inoculation. In addition, we did not observe a reduction in explant reactivation from PECs after infection with ΔUNG1 compared to ΔUNG1.MR (Fig. 9, summarized in Tables 1 and 2). We conclude that MHV68 latency establishment, reactivation from latency, and long-term maintenance in the peritoneal compartment is independent of the vUNG.

FIG 9.

MHV68 vUNG is not required for latency in the peritoneal exudate compartment after intraperitoneal inoculation. C57BL/6 mice were infected at 100 PFU by the intraperitoneal route with ΔUNG1.MR and ΔUNG1 MHV68 viruses. (A) Frequency of peritoneal exudate cells harboring latent genomes at 18 dpi. (B) Frequency of splenocytes spontaneously reactivating from latency at 18 dpi. (C) Frequency of peritoneal exudate cells harboring latent genomes at 42 dpi. For the limiting-dilution analyses, curve fit lines were determined by nonlinear regression analysis. The dashed lines represent 63.2%. Using Poisson distribution analysis, the intersection of the nonlinear regression curves with the dashed line was used to determine the frequency of cells that were either positive for the viral genome or reactivating virus. The data were generated from at least three independent experiments.

The viral UNG plays a critical role in replication in mouse cells with reduced host UNG activity.

A striking observation from our studies was the differential impact of the loss of the vUNG in various murine cells and tissues. We observed significant replication defects in primary MEFs and in the lung, but not in immortalized fibroblasts or in primary splenocytes. Although all murine tissues express UNG2, reduced UNG2 mRNA levels have previously been noted for lung tissue (2). We examined host UNGase levels between the different cell types infected by MHV68. We examined host UNG activity by incubating a uracil-containing single-stranded oligonucleotide with protein lysates from cells in culture and tissues from mice. Incubation with lysates from HEK293T cells, immortalized fibroblasts, or primary MEFs resulted in 98, 75, and 73% cleavage of the oligonucleotide, respectively (Fig. 10A). The block in cleavage in the presence of the UNG-specific inhibitor UGI confirmed that UNG is the major UDG responsible for uracil excision within these cell lysates. We observed robust UNGase activity in the naive spleen and PECs (Fig. 10B) tissues where the vUNG is dispensable. In sharp contrast, UNG activity in the lung was undetectable, indicating that the lung tissue is nearly devoid of host UNG expression. We observed a slight increase in UNGase activity in the lungs and PECs upon infection with MHV68, but the level of UNG activity in the lungs was comparable upon infection with ΔUNG1 and ΔUNG1.MR (Fig. 10C). This may be attributed to the immune infiltrate in the infected lung. Overall, the reduction in acute replication in the lungs upon loss of the vUNG correlated with impaired host UNG activity in this tissue. These data are consistent with a requirement for the vUNG to compensate for the absence of the host enzyme in tissues that are critical for viral replication.

FIG 10.

Analysis of uracil DNA glycosylase activity in cells and tissues that MHV68 infects. Denaturing polyacrylamide gel analysis of oligonucleotide cleavage upon incubation with lysates prepared from the indicated cells or tissue was performed. The percentage of cleavage relative to the negative control is indicated below each lane. (A) UNGase assay from cultured cell lysates; (B) lysates from mouse tissues; (C) lung lysates from naive mice or mice infected with either ΔUNG1.MR or ΔUNG1 at 7 dpi.

DISCUSSION

MHV68 encodes a functional UNG that promotes viral replication in primary fibroblasts and in the lungs of infected mice. This defect in replication within the lung delays latency establishment and reactivation in the spleen. Increasing the virus dose or bypassing the lungs altogether by intraperitoneal inoculation eliminates the requirement for the vUNG and identifies a route-dependent role for the vUNG. Finally, we observed various levels of host UNG activity in cells and tissues targeted by MHV68, with mouse lungs exhibiting the lowest levels of UNG activity. To our knowledge, this is the first report to directly correlate a tissue-specific absence of detectable host UNG activity with a requirement for vUNG.

Intranasal infection with MHV68 ΔUNG resulted in a dramatic reduction in replication in lung tissues that impaired latency establishment in the spleen. However, the ΔUNG latency defect was overcome with an increased dose of virus that largely restored lung titers. Bypassing the lung altogether by changing the route of virus administration to intraperitoneal inoculation fully restored latency. This supports a role for the vUNG in virus dissemination from initial sites of virus entry or replication to latent reservoirs, a finding consistent with studies in a mouse model of HSV-1 lacking the vUNG (UL2) (18). Primary HSV-1 infection occurs in the epithelium, after which the virus traverses the peripheral nervous system to invade the central nervous system. In contrast to WT virus-infected mice, mice infected with HSV-1ΔUNG (ΔUL2) virus did not exhibit either hind limb paralysis or encephalitis. Moreover, loss of the HSV-1 vUNG (UL2) led to reduced virus titers in the footpads and tissues of the peripheral and central nervous system (18).

The route-dependent phenotype of MHV68 ΔUNG is similar to pathogenesis studies of other replication accessory proteins. MHV68 mutants lacking the ribonucleotide reductase small subunit (RNR-S/ORF60) (32), the ribonucleotide reductase large subunit (RNR-L/ORF61) (33) or thymidine kinase (TK/ORF21) (34, 35) are unable to establish latency after an upper respiratory infection and yet exhibit normal latency establishment upon intraperitoneal inoculation (32–35). Moreover, similar to the data reported here, infections with an increased dose of the RNR-S null virus helped overcome the latency defect upon upper respiratory infection. Thus, our data for the vUNG are consistent with a model whereby the virus requires these “accessory” proteins in vivo to promote productive replication in primary cells lacking potent expression of host metabolic or repair enzymes (15, 18).

The absence of vUNG did not impact MHV68 reactivation from latent splenocytes or peritoneal exudate cells. Moreover, maintenance of latency 6 weeks postinfection was not impaired. At first glance, this observation contrasts with reactivation defects that were observed in mice infected with a mutant HSV-1 lacking UNG. However, HSV-1 reactivation was measured post-explant from trigeminal ganglia: a tissue composed of terminally differentiated adult neurons with low levels of host UNG (18, 36). Reactivation is also reduced in human gammaherpesvirus latency cell systems lacking the EBV viral UNG (BKRF3) alone or in the absence of both the vUNG and the host UNG (13, 18, 37–39). Interestingly, Su et al. (13) recently reported that host UNG2 levels decrease as EBV reactivation proceeds, indicating that the viral UNG is needed to promote replication under conditions of low host UNG levels (13). We attribute the lack of a reactivation defect for MHV68 ΔUNG to the latency reservoir under analysis at 16 to 18 dpi: actively proliferating peritoneal exudate cells or germinal center CD95hi B cells with high levels of host UNG2 (40).

Our data clearly demonstrate an important role for the vUNG in virus replication in the lung that is largely devoid of host UNG, and yet the mechanisms by which the host and viral UNGs contribute to gammaherpesvirus replication are not well characterized. The EBV and HSV-1 vUNG (UL2) promote viral DNA replication (13, 15, 41). Interaction of the HSV-1 origin binding protein with the OriS is impaired by the presence of uracils in the target sequence (42). The requirement of EBV UNG (BKRF3) for DNA replication during reactivation from latency appears to be largely independent of glycosylase function, suggesting that vUNG protein interactions with other viral or host replication factors might play a role (13). However, the specific role the vUNG plays in viral replication complex formation, fork progression, and DNA repair is not known.

B lymphocytes utilize UNG activity in class switch recombination and somatic hypermutation, two processes critical for the development of a diverse antibody repertoire required for host immunity. To mediate class switch recombination, AID deaminates cytosines in immunoglobulin switch regions to generate deoxyuridine which is then excised by two host DNA glycosylases: UNG2 and, to a lesser extent, SMUG1. MHV68 UNG can substitute for host UNG2 in class switch recombination. This novel finding suggests that the MHV68 UNG retains the ability to recognize and cleave the N-glycosidic bond of uracil and may interact with other proteins critical for the mutagenic process of CSR. This implicates a possible role for the vUNG in impacting B cell processes critical for gammaherpesvirus pathogenesis. Alternatively, given that gammaherpesviruses target B cells that undergo isotype-class switching and, in some reports, upregulate the B cell specific host cytidine deaminase, AID (39, 43), it is possible that mutagenic effects of AID may exert a selective pressure that must be countered by the vUNG. Indeed, overexpression of AID impairs reactivation in KSHV-positive latent BCBL cell lines, and this defect is exacerbated with depletion of host UNG2 (39). A role for the vUNG in countering AID restriction of gammaherpesvirus pathogenesis has not been studied. We recently reported that MHV68 replication is restricted by several host antiviral APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases (44). However, we did not observe an enhanced restriction by the most restrictive APOBEC3, APOBEC3A, in the absence of the viral UNG (data not shown).

Overall, our data support a model wherein the herpesvirus vUNG is required to promote viral replication under conditions of low host UNG levels. Importantly, we extend this finding to an in vivo gammaherpesvirus system and demonstrate that vUNG-dependent replication at the site of initial infection in the host has a substantial influence on the kinetics of dissemination and establishment of latency in distal reservoirs. Structure-function studies will be required to address differences between host and viral UNGs and dissect the possible roles played by the vUNG during replication. Given the critical role for the herpesvirus vUNG across all subfamilies, the vUNGs merit further investigation as targets of intervention to block herpesvirus replication and infection-associated diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Steven Reddy for technical support and the laboratories of Erich Mackow and Nancy Reich for sharing critical equipment. We also thank Upasana Roy and Orlando Scharer for assisting with the UNGase assays, as well as helpful discussions regarding UNG function.

L.T.K. was supported by an American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant RSG-11-160-01-MPC. L.T.K. and K.M. were supported by NIH AI111129-01. D.O. and D.W. are supported by the Gundersen Medical Foundation.

N.M., D.O., D.W., M.M., K.M., and L.T.K. designed the experiments. N.M., D.O., M.M, and K.M. executed the experiments. N.M., D.O., D.W., M.M., K.M., C.P., and L.T.K analyzed the data. N.M., D.O., D.W., K.M., and L.T.K. prepared the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Krokan HE, Drablos F, Slupphaug G. 2002. Uracil in DNA: occurrence, consequences and repair. Oncogene 21:8935–8948. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nilsen H, Steinsbekk KS, Otterlei M, Slupphaug G, Aas PA, Krokan HE. 2000. Analysis of uracil-DNA glycosylases from the murine Ung gene reveals differential expression in tissues and in embryonic development and a subcellular sorting pattern that differs from the human homologues. Nucleic Acids Res 28:2277–2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kavli B, Sundheim O, Akbari M, Otterlei M, Nilsen H, Skorpen F, Aas PA, Hagen L, Krokan HE, Slupphaug G. 2002. hUNG2 is the major repair enzyme for removal of uracil from U:A matches, U:G mismatches, and U in single-stranded DNA, with hSMUG1 as a broad specificity backup. J Biol Chem 277:39926–39936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nilsen H, Krokan HE. 2001. Base excision repair in a network of defense and tolerance. Carcinogenesis 22:987–998. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.7.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akbari M, Otterlei M, Pena-Diaz J, Aas PA, Kavli B, Liabakk NB, Hagen L, Imai K, Durandy A, Slupphaug G, Krokan HE. 2004. Repair of U/G and U/A in DNA by UNG2-associated repair complexes takes place predominantly by short-patch repair both in proliferating and growth-arrested cells. Nucleic Acids Res 32:5486–5498. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imai K, Slupphaug G, Lee WI, Revy P, Nonoyama S, Catalan N, Yel L, Forveille M, Kavli B, Krokan HE, Ochs HD, Fischer A, Durandy A. 2003. Human uracil-DNA glycosylase deficiency associated with profoundly impaired immunoglobulin class-switch recombination. Nat Immunol 4:1023–1028. doi: 10.1038/ni974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen R, Wang H, Mansky LM. 2002. Roles of uracil-DNA glycosylase and dUTPase in virus replication. J Gen Virol 83:2339–2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy SM, Williams M, Cohen JI. 1998. Expression of a uracil DNA glycosylase (UNG) inhibitor in mammalian cells: varicella-zoster virus can replicate in vitro in the absence of detectable UNG activity. Virology 251:393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pyles RB, Thompson RL. 1994. Mutations in accessory DNA replicating functions alter the relative mutation frequency of herpes simplex virus type 1 strains in cultured murine cells. J Virol 68:4514–4524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prichard MN, Duke GM, Mocarski ES. 1996. Human cytomegalovirus uracil DNA glycosylase is required for the normal temporal regulation of both DNA synthesis and viral replication. J Virol 70:3018–3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bogani F, Chua CN, Boehmer PE. 2009. Reconstitution of uracil DNA glycosylase-initiated base excision repair in herpes simplex virus 1. J Biol Chem 284:16784–16790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.010413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strang BL, Coen DM. 2010. Interaction of the human cytomegalovirus uracil DNA glycosylase UL114 with the viral DNA polymerase catalytic subunit UL54. J Gen Virol 91:2029–2033. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.022160-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Su MT, Liu IH, Wu CW, Chang SM, Tsai CH, Yang PW, Chuang YC, Lee CP, Chen MR. 2014. Uracil DNA glycosylase BKRF3 contributes to Epstein-Barr virus DNA replication through physical interactions with proteins in viral DNA replication complex. J Virol 88:8883–8899. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00950-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prichard MN, Lawlor H, Duke GM, Mo C, Wang Z, Dixon M, Kemble G, Kern ER. 2005. Human cytomegalovirus uracil DNA glycosylase associates with ppUL44 and accelerates the accumulation of viral DNA. Virol J 2:55. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-2-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Courcelle CT, Courcelle J, Prichard MN, Mocarski ES. 2001. Requirement for uracil-DNA glycosylase during the transition to late-phase cytomegalovirus DNA replication. J Virol 75:7592–7601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bogani F, Corredeira I, Fernandez V, Sattler U, Rutvisuttinunt W, Defais M, Boehmer PE. 2010. Association between the herpes simplex virus-1 DNA polymerase and uracil DNA glycosylase. J Biol Chem 285:27664–27672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.131235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weller SK, Coen DM. 2012. Herpes simplex viruses: mechanisms of DNA replication. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol 4:a013011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pyles RB, Thompson RL. 1994. Evidence that the herpes simplex virus type 1 uracil DNA glycosylase is required for efficient viral replication and latency in the murine nervous system. J Virol 68:4963–4972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McBride KM, Gazumyan A, Woo EM, Barreto VM, Robbiani DF, Chait BT, Nussenzweig MC. 2006. Regulation of hypermutation by activation-induced cytidine deaminase phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:8798–8803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gazumyan A, Timachova K, Yuen G, Siden E, Di Virgilio M, Woo EM, Chait BT, Reina San-Martin B, Nussenzweig MC, McBride KM. 2011. Amino-terminal phosphorylation of activation-induced cytidine deaminase suppresses c-myc/IgH translocation. Mol Cell Biol 31:442–449. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00349-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collins CM, Speck SH. 2012. Tracking murine gammaherpesvirus 68 infection of germinal center B cells in vivo. PLoS One 7:e33230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tischer BK, Smith GA, Osterrieder N. 2010. En passant mutagenesis: a two step markerless red recombination system. Methods Mol Biol 634:421–430. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-652-8_30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weck KE, Barkon ML, Yoo LI, Speck SH, Virgin HI. 1996. Mature B cells are required for acute splenic infection, but not for establishment of latency, by murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J Virol 70:6775–6780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weck KE, Kim SS, Virgin HI, Speck SH. 1999. B cells regulate murine gammaherpesvirus 68 latency. J Virol 73:4651–4661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Upton JW, van Dyk LF, Speck SH. 2005. Characterization of murine gammaherpesvirus 68 v-cyclin interactions with cellular cdks. Virology 341:271–283. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jia Q, Sun R. 2003. Inhibition of gammaherpesvirus replication by RNA interference. J Virol 77:3301–3306. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.5.3301-3306.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim YJ, Wilson DM III. 2012. Overview of base excision repair biochemistry. Curr Mol Pharmacol 5:3–13. doi: 10.2174/1874467211205010003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rada C, Williams GT, Nilsen H, Barnes DE, Lindahl T, Neuberger MS. 2002. Immunoglobulin isotype switching is inhibited and somatic hypermutation perturbed in UNG-deficient mice. Curr Biol 12:1748–1755. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tischer BK, von Einem J, Kaufer B, Osterrieder N. 2006. Two-step red-mediated recombination for versatile high-efficiency markerless DNA manipulation in Escherichia coli. Biotechniques 40:191–197. doi: 10.2144/000112096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weck KE, Kim SS, Virgin HI, Speck SH. 1999. Macrophages are the major reservoir of latent murine gammaherpesvirus 68 in peritoneal cells. J Virol 73:3273–3283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barton E, Mandal P, Speck SH. 2011. Pathogenesis and host control of gammaherpesviruses: lessons from the mouse. Annu Rev Immunol 29:351–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-072710-081639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milho R, Gill MB, May JS, Colaco S, Stevenson PG. 2011. In vivo function of the murid herpesvirus-4 ribonucleotide reductase small subunit. J Gen Virol 92:1550–1560. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.031542-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gill MB, May JS, Colaco S, Stevenson PG. 2010. Important role for the murid herpesvirus 4 ribonucleotide reductase large subunit in host colonization via the respiratory tract. J Virol 84:10937–10942. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00828-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coleman HM, de Lima B, Morton V, Stevenson PG. 2003. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 lacking thymidine kinase shows severe attenuation of lytic cycle replication in vivo but still establishes latency. J Virol 77:2410–2417. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.4.2410-2417.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gill MB, Wright DE, Smith CM, May JS, Stevenson PG. 2009. Murid herpesvirus-4 lacking thymidine kinase reveals route-dependent requirements for host colonization. J Gen Virol 90:1461–1470. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.010603-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Focher F, Mazzarello P, Verri A, Hubscher U, Spadari S. 1990. Activity profiles of enzymes that control the uracil incorporation into DNA during neuronal development. Mutat Res 237:65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu CC, Huang HT, Wang JT, Slupphaug G, Li TK, Wu MC, Chen YC, Lee CP, Chen MR. 2007. Characterization of the uracil-DNA glycosylase activity of Epstein-Barr virus BKRF3 and its role in lytic viral DNA replication. J Virol 81:1195–1208. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01518-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verma SC, Bajaj BG, Cai Q, Si H, Seelhammer T, Robertson ES. 2006. Latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus recruits uracil DNA glycosylase 2 at the terminal repeats and is important for latent persistence of the virus. J Virol 80:11178–11190. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01334-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bekerman E, Jeon D, Ardolino M, Coscoy L. 2013. A role for host activation-induced cytidine deaminase in innate immune defense against KSHV. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003748. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gramlich HS, Reisbig T, Schatz DG. 2012. AID-targeting and hypermutation of non-immunoglobulin genes does not correlate with proximity to immunoglobulin genes in germinal center B cells. PLoS One 7:e39601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fixman ED, Hayward GS, Hayward SD. 1995. Replication of Epstein-Barr virus oriLyt: lack of a dedicated virally encoded origin-binding protein and dependence on Zta in cotransfection assays. J Virol 69:2998–3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Focher F, Verri A, Verzeletti S, Mazzarello P, Spadari S. 1992. Uracil in OriS of herpes simplex 1 alters its specific recognition by origin binding protein (OBP): does virus induced uracil-DNA glycosylase play a key role in viral reactivation and replication? Chromosoma 102:S67–S71. doi: 10.1007/BF02451788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim JH, Kim WS, Park C. 2013. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 increases genomic instability through Egr-1-mediated upregulation of activation-induced cytidine deaminase in B-cell lymphoma. Leukemia Lymphoma 54:2035–2040. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.769218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Minkah N, Chavez K, Shah P, Maccarthy T, Chen H, Landau N, Krug LT. 2014. Host restriction of murine gammaherpesvirus 68 replication by human APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases but not murine APOBEC3. Virology 454-455:215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]