Abstract

The ‘ostium primum’ defect is still frequently considered to be the consequence of deficient atrial septation, although the key feature is a common atrioventricular junction. The bridging leaflets of the common atrioventricular valve, which are joined to each other, are depressed distal to the atrioventricular junction, and fused to the crest of the muscular ventricular septum, which is bowed in the concave direction towards the ventricular apex. As a result, shunting across the defect occurs between the atrial chambers. These observations suggest that the basic deficiency in the ‘ostium primum’ defect is best understood as a product of defective atrioventricular septation, rather than an atrial septal defect. We have now encountered four examples of ‘ostium primum’ defects in mouse embryos that support this view. These were identified from a large number of mouse embryo hearts collected from a normal, outbred mouse colony and analysed by episcopic microscopy as part of an ongoing study of normal mouse cardiac development. The abnormal hearts were identified from embryos collected at embryonic days 15.5, 16.5 and 18.5 (two cases). We have analysed the features of the abnormal hearts, and compared the findings with those obtained in the large number of normally developed embryos. Our data show that the key feature of normal atrioventricular septation is the ventral growth through the right pulmonary ridge of a protrusion from the dorsal pharyngeal mesenchyme, confirming previous findings. This protrusion, known as the vestibular spine, or the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion, reinforces the closure of the primary atrial foramen, and muscularises along with the mesenchymal cap of the primary atrial septum to form the ventro-caudal buttress of the oval foramen, identified by some as the ‘canal septum’. Detailed analysis of the four abnormal hearts suggests that in each case there has been failure of growth of the vestibular spine, with the result that the common atrioventricular junction found earlier during normal development now persists during cardiac development. Failure of separation of the common junction also accounts for the trifoliate arrangement of the left atrioventricular valve in the abnormal hearts. Analysis of the episcopic datasets also permits recognition of the location of the atrioventricular conduction axis. Comparison of the location of this tract in the normal and abnormal hearts shows that there is no separate formation of a ventricular component of the ‘canal septum’ as part of normal development. We conclude that it is abnormal formation of the primary atrial septum that is the cause of so-called ‘secundum’ atrial septal defects, whereas it is the failure to produce a second contribution to atrial septation (via growth of the vestibular spine) that results in the ‘ostium primum’ defect.

Keywords: atrioventricular septal defect, endocardial cushions, heart, primary atrial septum, vestibular spine

Introduction

Much has been learned over the past two decades concerning the molecular mechanisms underscoring cardiac development. Knowledge concerning the morphological changes accompanying the mechanistic processes, however, has not always kept pace with the molecular findings. When considering the fate of the atrioventricular endocardial cushions, it has often been presumed that they form a ‘valvoseptal complex’, the inference being that contributions are made by the cushions to the atrial and ventricular septal structures (Geva, 2009), even though evidence for such contributions in mammalian hearts, to the best of our knowledge, is thus far lacking (Briggs et al. 2012). The three-dimensional and temporal events occurring during cardiac development, however, are remarkably complex. The complexity makes it difficult to appreciate the anatomical changes induced by the remoulding of the developmental components. Understanding has now been facilitated by the development of high-resolution episcopic microscopy (Mohun & Weninger, 2011). It is now possible to reconstruct with accuracy the morphological changes taking place in the developing heart, thus revealing the changes in position of the various components of the septal and valvar structures. In this investigation, we show how access to 3D models from normally developing mice has facilitated a clearer understanding of the formation of the atrioventricular junctions and septal structures.

During the interrogation of a large number of datasets obtained from an outbred, normal mouse colony, we serendipitously discovered four embryos in which the hearts showed ‘ostium primum’ defects. Further analysis of these datasets confirms observations made in the clinical setting (Becker & Anderson, 1982), namely that the phenotypic feature of the ‘ostium primum’ defect is the commonality of the atrioventricular junction, along with unwedging of the aortic root. The mouse data show, furthermore, that the shunting between the atrial chambers occurs through an atrioventricular, rather than an atrial, septal defect.

The commonality of the atrioventricular junction also directs attention to the trifoliate configuration of the left atrioventricular valve. It has been the description of this valve as a ‘cleft mitral valve’ (Von Rokitansky, 1875) that has, in many respects, held back the understanding of not only the morphology, but also the morphogenesis of hearts with common atrioventricular junction. Prior to the illustrations produced by Von Rokitansky, Peacock had provided a remarkably accurate account of the ostium primum lesion, emphasising the ‘distinctly tricuspid appearance of the left auriculo-ventricular valve’, along with the fact that the defect was ‘at the base of the inter-auricular septum’ (Peacock, 1846). It was only subsequent to the appearance of Von Rokitansky's atlas that it became customary to interpret the ostium primum defect in terms of deficient atrial septation, although it was well recognised that its cardinal feature was an atrioventricular canal defect (Van Mierop et al. 1962). By that time, furthermore, it had become conventional wisdom to describe the overall group of atrioventricular canal defects in terms of ‘endocardial cushion defects’.

Comparisons made between our normal and malformed hearts show how the atrioventricular endocardial cushions, which provide the basis for formation of the normal mitral valve, retain their initially trifoliate configuration when atrioventricular septation is deficient. Our data also provide evidence in support of the view that the ‘spina vestibuli’ (or ‘vestibular spine’ in English; His, 1885) plays a crucial role in separating the right and left atrioventricular junctions (Webb et al. 1998). Inadequate formation of this structure, also now known as the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion (Snarr et al. 2007), has been suggested to be involved in persistence of the common atrioventricular junction (Blom et al. 2003; Briggs et al. 2013). Our current findings add further support to this notion.

Materials and methods

We have studied over 300 datasets prepared by high-resolution episcopic microscopy showing the structure of the developing heart in wild-type mice of an outbred background (NIMR Parkes) from embryonic day (E) 9.5 to term (Table1). The mice were collected as part of an extensive study of normal and abnormal cardiac development undertaken at the National Institute of Medical Research. Details of the technique for episcopic microscopy have been provided by Mohun & Weninger (2011). When examining the datasets, we identified one embryo at E15.5, another at E16.5, and two at E18.5, with atrioventricular septal defects in the setting of common atrioventricular junctions, but with separate valvar orifices for the right and left ventricles. These lesions, therefore, comprise ‘ostium primum’ defects. These were the only embryos found with ostium primum defects of 231 examined at or subsequent to E13.5, the anticipated time of completion of atrial septation.

Table 1.

The numbers of embryos from the archive maintained at the National Institute of Medical Research, Mill Hill, London, which were examined to establish the steps involved in normal and abnormal formation of the atrial and atrioventricular septums

| E9.5 | 10 torsos |

| E10.5 | 14 torsos |

| E11.5 | 59 (8 torsos) |

| E12.5 | 13 |

| E13.5 | 30 |

| E14.5 | 78 |

| E15.5 | 53 |

| E16.5 | 26 |

| E17.5 | 30 |

| E18.5 | 14 |

| Total | 327 |

All the embryos from embryonic (E) days 9.5 and 10.5, and eight of those from E11.5, were embedded as torsos, permitting examination of the entire developing thorax. In all of the embryos from the subsequent days, the heart was removed from the thorax and sectioned as an isolated organ.

We have compared the differences in the structure of the atrial and ventricular septums, and the left atrioventricular valve, in the normally developing heart, and in the datasets showing the ostium primum defects. We were also able to recover the sections from two of the serially sectioned embryos with ostium primum defects. By staining these with haematoxylin and eosin, we were able to confirm the location of an insulated tract corresponding to the known location of the atrioventricular conduction axis. The histological findings confirmed our initial identification based upon interrogation of 3D reconstructions. It was not possible to use specific markers to confirm the location of the structures identified as the conduction axis in our episcopic datasets. We were able, nonetheless, to compare findings for the ostium primum defects with the normal arrangement. The axis in the normally developing hearts, as in the hearts with ostium primum defects, was identified morphologically on the basis of the rules established in 1910 – namely the ability to follow the tract from section to section, with the cells within the tract showing morphological differences relative to the adjacent structures, and with additional tissues separating the tract from the neighbouring myocardium (Aschoff, 1910; Mönckeberg, 1910).

Results

Normal hearts

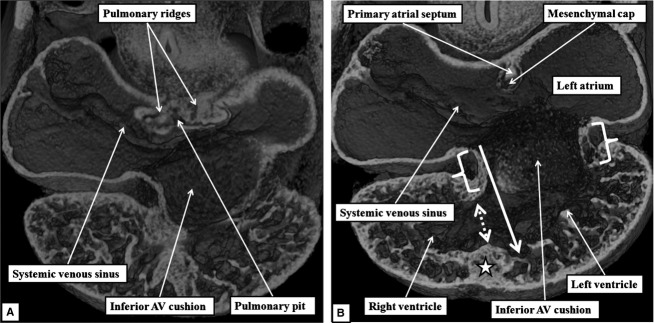

By E10.5, the scene has been set for the beginning of atrial and ventricular septation. At this stage, the systemic venous tributaries have rotated around the persisting dorsal mesocardial connection between the atrial component of the primary heart tube and the pharyngeal mesenchyme. As a result, all the blood is draining to the right side of the common atrial chamber. The mesocardial connection itself is a portal between the pharyngeal mesenchyme and the atrial cavity, its atrial surface being bounded by the pulmonary ridges, with the right ridge more prominent than the left (Fig.1A). The pulmonary vein, which canalises within the pharyngeal mesenchyme concomitant with development of the lungs, uses the dorsal mesocardial portal to enter the atrial cavity. The site of entry is to the left side of the plane of the primary atrial septum, which grows caudally from the atrial roof towards the atrioventricular cushions located within the atrioventricular canal (Fig.1B). The ventricular component of the heart has already looped, with the apical component of the future left ventricle ballooning apically from the inlet part of the loop, and the right ventricular apical component ballooning from the outlet part of the heart tube. The atrioventricular canal at this stage is recognisable as a discrete ring of musculature, which surrounds the prominent superior and inferior atrioventricular cushions.

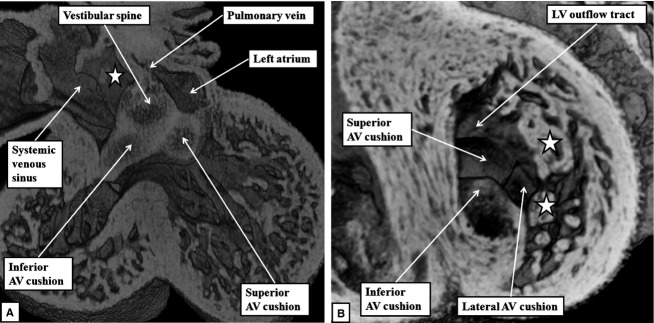

Fig 1.

The images, from episcopic datasets from developing mice at embryonic (E) day 10.5, show the initial site of formation of the primary atrial septum and the primary atrial foramen. (A) The dorsal mesocardial connection, (B) the site of formation of the primary atrial septum in the atrial roof. Note the location of the primordium of the apical muscular ventricular septum (star). The interventricular communication (dashed double-headed white arrow) at this stage has the inner heart curvature as its cranial margin, as the developing primary atrial septum is malaligned relative to the developing apical ventricular septum. The white brackets show the atrioventricular (AV) canal musculature, which surrounds the opening of the atrioventricular canal. The right side of the orifice of the canal, at this stage, opens to the apical component of the developing left ventricle (white arrow).

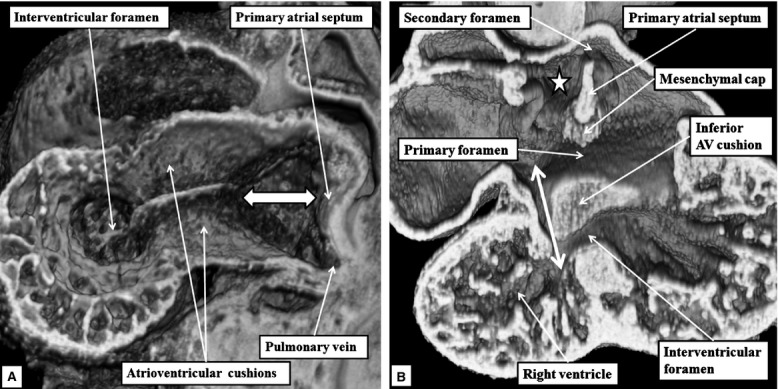

The appearance of the primary atrial septum in the atrial roof makes it possible to identify the primary atrial foramen, which is bounded cranially by the leading edge of the primary atrial septum, and caudally by the atrial margins of the atrioventricular cushions (Fig.2A). Marked changes occur in the relationships and alignment of the septal components during E10.5 and 11.5. At the start of these days of development, the atrioventricular cushions remain unfused. The atrioventricular canal, however, has expanded rightward so that the cavity of the right atrium is in direct connection with the right ventricular cavity (Fig.2B). At the same time, the primary atrial septum, covered by a mesenchymal cap, has grown towards the atrial margins of the cushions, thus reducing markedly the size of the primary atrial foramen. So as to continue to provide an inter-atrial communication, its upper margin has broken away from the atrial roof, thus producing the secondary atrial foramen (Fig.2B). The primary atrial foramen itself is bounded on all its borders by mesenchymal tissues, as the developing septum carries a mesenchymal cap on its leading edge. When traced caudally, the mesenchymal cap is continuous with the area of the right pulmonary ridge, which has further expanded relative to the size of the left ridge. The expansion of the right ridge confines the orifice of the pulmonary vein to the cavity of the developing left atrium. The expanded right ridge itself is also mesenchymal, and can be traced dorsally into continuity with the pharyngeal mesenchyme (Fig.3A). Assessment from the ventral aspect shows that the swelling protrudes into the cavity of the developing right atrium (Fig.3B). A structure in this location was initially described over 150 years ago by Wilhelm His, who termed it the ‘spina vestibuli’. We, and others (Blom et al. 2003), now describe it as the vestibular spine. It is also known as the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion (Snarr et al. 2007).

Fig 2.

(A) Prepared in the sagittal plane and viewed from the left, from a dataset at E10.5. At this stage, the atrioventricular (AV) canal opens to the cavity of the developing left ventricle. The view from the left shows how the primary atrial foramen (double-headed white arrow with black borders) is bounded cranially by the primary atrial septum, and caudally by the atrial surfaces of the atrioventricular cushions, which are located superiorly and inferiorly within the canal. (B) A frontal section at E11.5, by which time the atrioventricular canal has expanded so that the cavity of the right atrium is opening into the inlet of the developing right ventricle (double-headed white arrow). The primary septum has broken away from the atrial roof to form the secondary inter-atrial communication. The primary septum itself, however, is now aligned to the developing muscular ventricular septum, although the inferior atrioventricular cushion has yet to fuse to the ventricular septal crest. The primary atrial foramen is now bounded by the mesenchymal cap cranially, and the atrial surface of the atrioventricular cushions caudally. The white star with black borders in this, and subsequent images, shows the gap between the left venous valve and the developing atrial septum, known as the interseptovalvar space.

Fig 3.

The images, in the frontal plane, are from developing mice at the beginning of E11.5. (A) This image confirms that, as shown in Fig.2B, expansion of the atrioventricular canal (AV) has brought the cavity of the right atrium into direct continuity with that of the right ventricle. The section shows how the expansion of the mesenchymal tissue within the right pulmonary ridge, forming the vestibular spine, commits the orifice of the pulmonary vein to the developing left atrium. (B) This image, taken more ventrally, shows how growth of the primary septum towards the atrioventricular cushions has reduced the size of the primary atrial foramen. The reconstruction shows how the spine protrudes ventrally into the cavity of the developing right atrium, with its point overlapping the mesenchymal cap carried on the leading edge of the primary atrial septum.

By the end of E11.5, the major atrioventricular cushions themselves have fused, thus separating the atrioventricular canal into right and left orifices. By this stage, lateral cushions have been formed at the parietal margins of the newly established right and left atrioventricular junctions. With the establishment of the direct connection between the cavities of the right atrium and developing right ventricle, as shown in Fig.2B, the embryonic interventricular foramen is bounded caudally by the crest of the muscular ventricular septum, and cranially by the ventricular surface of the fused atrioventricular cushions. By E12.5, the mesenchymal cap on the primary septum has fused with the atrial margins of the atrioventricular cushions, thus obliterating the primary atrial foramen, with the vestibular spine contributing to closure of the dorsal margin of the area of fusion (Fig.4A). Within the left ventricle, the ventricular surfaces of the endocardial cushions are continuous laterally with the trabecular layer of the ventricular wall, with the primordiums of the papillary muscles of the mitral valve now becoming evident. At this stage, the arrangement of the endocardial cushions within the left ventricle, when viewed from the apical aspect, gives the developing mitral valve an obviously trifoliate configuration (Fig.4B).

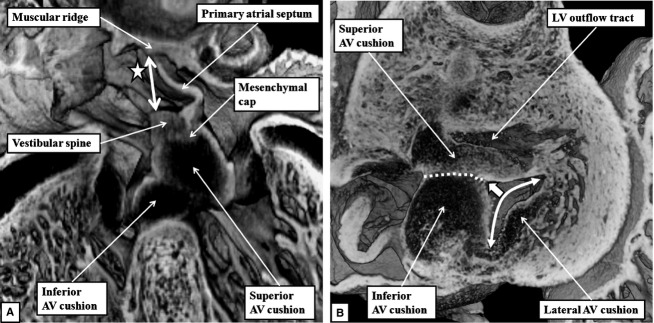

Fig 4.

The episcopic images are from datasets prepared from developing mice at E12.5. (A) This image, in the frontal plane, shows how the atrioventricular (AV) cushions have fused with each other, and how the vestibular spine has fused caudally with their atrial margins, completing the commitment of the pulmonary vein to the left atrium (compare with Fig.3A). (B) This image, in short axis, shows how the developing mitral valve, at this stage, has an obviously trifoliate arrangement formed by the appositions of the lateral margins of the superior and inferior atrioventricular cushions with the lateral cushion. The ventricular surfaces of the cushions are continuous apically with the trabecular layer of the ventricular wall. Note the locations of the developing primordiums of the papillary muscles of the mitral valve (stars). LV, left ventricle.

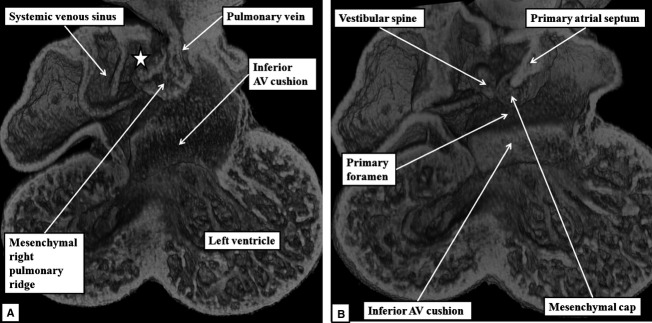

By the end of E13.5, the variability in the textures of the tissues as seen in the episcopic reconstructions reveal the contributions made by the vestibular spine to what is becoming the ventro-caudal buttress of the atrial septum. By this time, a muscular ridge has formed at the initial site of breakdown of the primary septum from the atrial roof, although there is no continuing ventral or cranial growth of this ridge. Eventually, the ridge is incorporated into the cranial margin of the right atrial rim of the oval foramen (see below). Continuing ventral growth of the vestibular spine now reinforces the right atrial side of the areas of fusion of the mesenchymal cap with the inferior atrioventricular cushion (Fig.5A). By E14.5, the fusion of the right ventricular margins of the atrioventricular cushions with the proximal outflow cushions has closed the persisting embryonic interventricular communication, thus walling the aorta into the left ventricle (Odgers, 1937/38; Anderson et al. 2014). The incorporation of the subaortic outflow tract within the left ventricle, combined with an increase in length of the lateral atrioventricular cushion, now gives the mitral valvar orifice a bifoliate appearance (Fig.5B).

Fig 5.

(A) This image, prepared from an episcopic dataset from a developing mouse at E13.5, and taken in four-chamber orientation, shows how it remains possible to recognise the contributions made by the atrioventricular (AV) cushions, the vestibular spine and the mesenchymal cap in closing the primary atrial foramen. The vestibular spine, together with the cap, now form the ventro-caudal margin of the developing oval foramen. The right atrial margin of the foramen (double-headed white arrow) is bounded cranially by the small muscular ridge now formed at the site of breakdown of the cranial margin of the primary septum. (B) This image, a short axis section from a mouse at E14.5, shows how the fusion of the two major atrioventricular cushions (white dotted line), together with expansion of the lateral cushion, is beginning to provide a bifoliate configuration for the developing mitral valve (double-headed white arrow). There is a small cleft (white arrow with black margins) at this stage within what will become the aortic leaflet of the mitral valveLV, left ventricle.

By E15.5, the atrioventricular cushions have diminished in size, forming the insulating plane between the structure now recognisable as the ventro-caudal buttress of the atrial septum and the crest of the muscular ventricular septum. Scanning through the episcopic datasets reveals the discrete myocardial tract that extends from the base of the muscularising buttress of the atrial septum through the insulating plane to reach the crest of the muscular ventricular septum (Fig.6). This tract occupies the site occupied in the postnatal heart by the atrioventricular conduction axis. The features recognisable within the episcopic datasets are themselves sufficient to satisfy the criterions established by Monkeberg and Aschoff for recognition of conducting tracts (Aschoff, 1910; Mönckeberg, 1910).

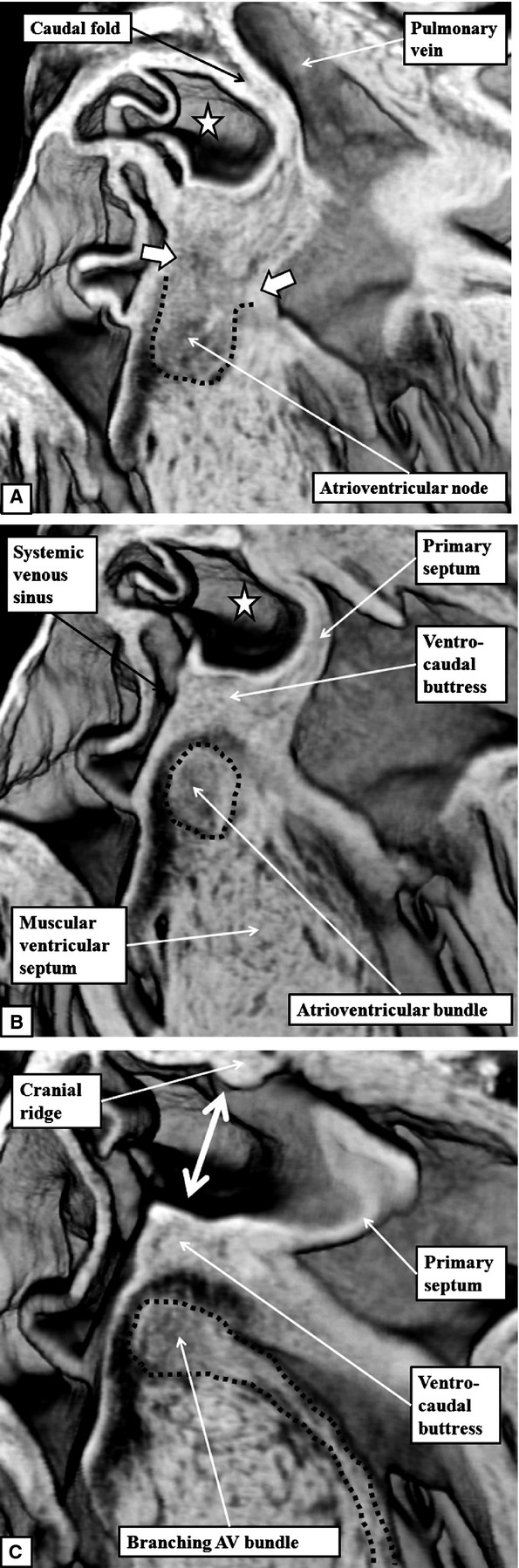

Fig 6.

The images are frontal sections taken across the oval fossa, with (A) taken dorsally and (C) ventrally, from an episcopic dataset prepared from a mouse embryo at E15.5. The images show how it is possible to trace the atrioventricular (AV) conduction axis from its origin in the atrioventricular node (A), through the penetrating atrioventricular bundle (B), to the branching bundle, which continues as the left bundle branch down the endocardial aspect of the ventricular septum (dotted lines in C). The sections also show the margins of the oval fossa (double-headed white arrow in C). The dorsal rim, seen in (A), is a fold between the wall of the right atrium and the pulmonary vein. The cranial margin, seen in (C), is the muscular ridge formed at the site of breakdown of the primary septum from the atrial roof. The ventro-caudal margin has now been formed by muscularisation of the vestibular spine and the mesenchymal cap carried on the leading edge of the atrial septum. Note that, in (A), the atrioventricular node is in continuity with the atrial cardiomyocytes developing within the atrial septum (white arrows with white borders). The dotted lines have been placed to show the boundaries between the axis and the adjacent myocardial tissues evident in the serial sections reconstructed to produce the episcopic dataset.

By E16.5, the margins of the oval foramen are well formed, producing the situation that continues to term, and providing the arrangement for postnatal closure of the foetal inter-atrial communication. Sections taken in the frontal plane show that the tissues of the vestibular spine and the mesenchymal cap have muscularised to form the ventro-caudal buttress of the atrial septum. The buttress binds the flap valve of the foramen, derived from the primary atrial septum, to the insulating plane provided by the fused atrioventricular cushions (Fig.7A). It can be considered to represent an atrial ‘canal septum’ (Geva, 2009). The remaining rims of the oval foramen have been formed by remodelling of the original walls of the right and left atrial chambers. The caudal rim is the fold between the interseptovalvar space of the right atrium and the pulmonary venous component of the left atrium. The cranial rim is the muscular ridge formed at the initial site of breakdown of the primary atrial septum. The primary septum itself now forms the floor of the oval foramen (Fig.7A). Within the ventricles, the subaortic outflow tract is now interposed fully between the newly formed aortic leaflet of the mitral valve and the muscular ventricular septum (Fig.7B). This arrangement is described as ‘wedging’ of the outflow tract between the mitral valve and the septum.

Fig 7.

The images are from an episcopic dataset prepared from a mouse embryo at E16.5. (A) This image, in four-chamber projection, shows the structure of the oval foramen (double-headed white arrow). The primary septum now forms its floor, with the ventro-caudal buttress derived by muscularisation of the vestibular spine along with the mesenchymal cap. The fused atrioventricular (AV) cushions now form the insulating plane between the atrial and ventricular septal structures. The cranial margin of the oval foramen is the muscular ridge developed at the initial site of breakdown of the primary septum away from the atrial roof. (B) This image is a short axis section across the left ventricle (LV). It shows how the mitral valve, by E15.5, has achieved its bifoliate pattern of closure along a solitary zone of apposition between its aortic and mural leaflets (double-headed white arrow). The subaortic outflow tract now interposes almost completely between the plane of mitral valvar opening and the muscular ventricular septum.

Abnormal hearts

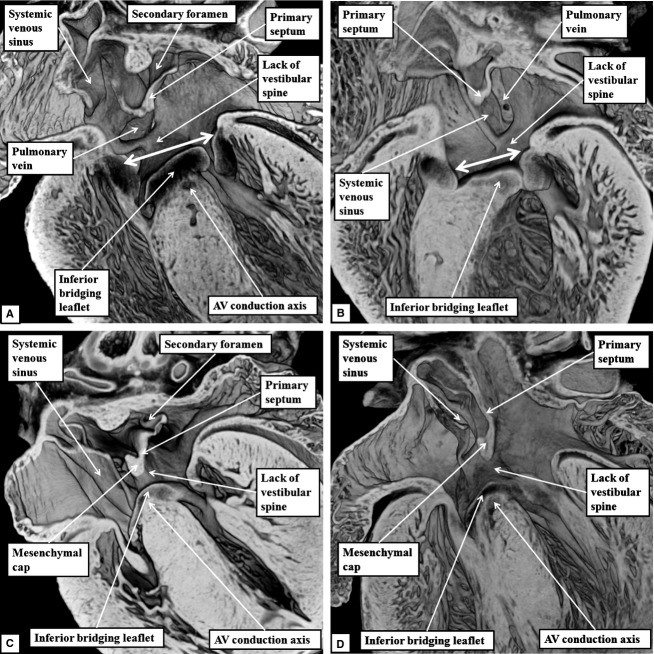

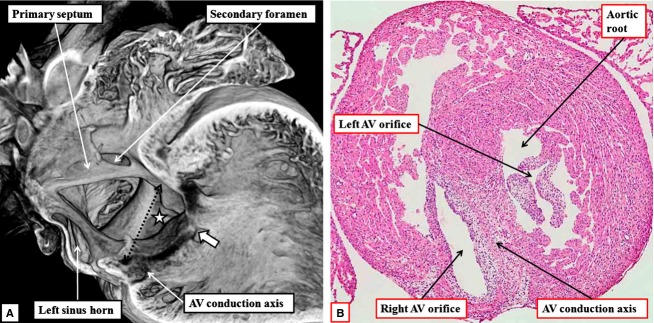

All four abnormal hearts showed the phenotypic features of atrioventricular septal defect, with separate right and left atrioventricular orifices within a common atrioventricular junction. This arrangement is the ‘ostium primum’ variant of inter-atrial communications. In each case, sectioning in the four-chamber frontal plane revealed retention of the common atrioventricular junction seen during earlier normal development (Fig.8). The septal defects, representing persistence of the ostium primum defect seen during earlier development, were bounded by the leading edge of the atrial septum cranially, and caudally by the atrial surface of the leaflets of the valve guarding the common atrioventricular junction. These leaflets, which bridged the crest of the muscular ventricular septum, were bound down firmly to the septal crest, thus dividing the common junction into separate valvar orifices for the right and left ventricles (Fig.8).

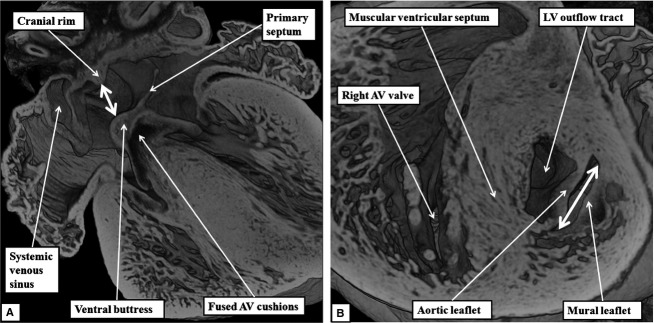

Fig 8.

The images are from the episcopic datasets prepared from the developing mice found to have ostium primum defects. (A) This image is from an embryo killed at E15.5; (B) an embryo killed at E16.5; and (C) and (D) from embryos killed at E18.5. All sections are prepared to replicate the echocardiographic four-chamber frontal plane. They all show the commonality of the atrioventricular (AV) junction (double-headed white arrows in A and B). In each dataset, it is also possible to recognise that, while the mesenchymal cap has muscularised to form a knob on the leading edge of the primary atrial septum, there has been no formation of the vestibular spine. The venous valves guarding the systemic venous sinus are located dorsally within the right atrial chamber. In each dataset, it is also possible to recognise the atrioventricular conduction axis sandwiched between the inferior bridging leaflet of the common atrioventricular valve and the crest of the muscular ventricular septum. The fusion of the inferior bridging leaflet to the crest of the muscular ventricular septum produces separate right and left atrioventricular valvar orifices within the common atrioventricular junction (see also Fig.9).

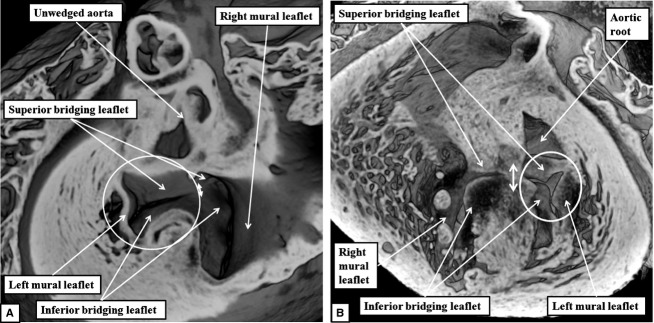

Assessement of the common atrioventricular junction in the short axis plane revealed that the leaflets bridging the ventricular septum were not only fused to the septal crest, but also to each other, thus producing the separate valvar orifices for the right and left ventricles (Fig.9). The orifice formed for the left ventricle was guarded by leaflets arranged in trifoliate fashion, in marked contrast to the bifoliate arrangement seen in the normally developed heart at this stage (Fig.7B).

Fig 9.

The images show the common atrioventricular junction in one of the abnormal mouse embryos found, at E18.5, to have persistence of the ostium primum defect. (A) This image shows the view of the junction from the atrial aspect. The bridging leaflets of the common atrioventricular valve are fused to each other (double-headed white arrow), thus dividing the common junction into separate orifices for the right and left ventricles. The left atrioventricular orifice is guarded by leaflets that close in trifoliate fashion (white circle), as confirmed by the view obtained from the ventricular apex (B). Both images show that the aortic root, unlike the situation in the normally developed heart (Fig.7B), is no longer wedged between the leaflets of the left atrioventricular valve and the ventricular septum. The dotted line in (B) shows the line of fusion between the bridging leaflets of the common atrioventricular valve.

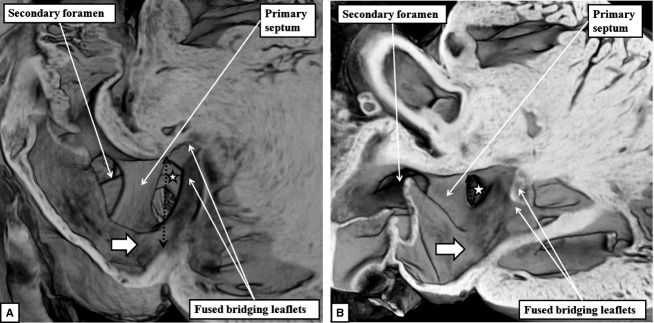

When analysed from the right side, we found marked variation in the size of the communication between the chambers provided by the ostium primum defect (compare Figs10A and 1A,B). Sectioning in the plane of the muscular ventricular septum confirmed that the bridging leaflets, derived from the superior and inferior atrioventricular cushions, were fused not only to each other, but also to the crest of the muscular ventricular septum. The ventricular septum itself was bowed towards the ventricular apex, with the fused cushions confining shunting across the ostium primum defect at atrial level (Figs10A and 11).

Fig 10.

(A) This image shows the right-sided view of the ostium primum defect in one of the mouse embryos killed at E18.5. In this mouse, the primary septum has failed to grow down to the level of the atrioventricular (AV) junction (double-headed dotted black arrow), and there has been no ventral growth of the vestibular spine, the systemic venous sinus forming the dorsal wall of the right atrial chamber. The muscular ventricular septum has also failed to grow cranially to the level of the atrioventricular junction. Because the bridging leaflets of the common valve are fused to each other (white arrow with black borders), but also to the crest of the bowed ventricular septum, part of the shunting across the ostium primum defect is distal to the level of the atrioventricular junction (white star with black borders). (B) This image, prepared by staining one of the original episcopic sections with haematoxylin and eosin, shows how the atrioventricular conduction axis is sandwiched between the bridging leaflets and the crest of the muscular ventricular septum. Note the trifoliate configuration of the left atrioventricular valvar orifice.

Fig 11.

The images show the varying size of the ostium primum defects in the embryonic mice with deficient atrioventricular septation. The defect is of good size in the image shown in (A), from an embryonic mouse killed at E18.5, but small in the one shown in (B), from the other embryo killed at E18.5. In both mice, shunting across the defect is distal to the plane of the atrioventricular junction (black dotted double-headed arrow) by virtue of the bridging leaflets of the common valve being depressed into the ventricular cavity and fused to the scooped-out ventricular septal crest. Shunting, therefore, is at atrial level even though it is below the level of the atrioventricular junction (white stars with black borders). Note also that the systemic venous sinus forms the dorsal wall of the right atrium, as there has been no ventral growth of the vestibular spine.

The septum, in essence, had failed to rise to the level of the atrioventricular junction, unlike in normal development. Examination of sections stained histologically demonstrated that, despite the bowed arrangement of the ventricular septum, the abnormal hearts retained a discernable atrioventricular conduction axis. This was still sandwiched between the undersurface of the valvar leaflets derived from the bridging leaflets and the crest of the muscular septum (Fig.10B). We, therefore, found no evidence to suggest that muscular tissue was missing from its crest that could be interpreted as representing a ventricular part of the ‘canal septum’ (Geva, 2009).

In the abnormal mice, the systemic venous sinus formed the dorsal wall of the right atrium. None showed normal ventral growth of the vestibular spine, even though the leading edge of the atrial septum itself possessed a well-formed rim, presumably formed by muscularisation of the mesenchymal cap (Fig.11A). In the embryos with larger defects, furthermore, the pulmonary vein opened centrally relative to the common atrioventricular junction (Fig.10A). All the embryonic mice with ostium primum defects had co-existing defects within the oval fossa, as at these stages the flap valve derived from the primary atrial septum had yet to fuse with the cranial rim of the oval foramen (Fig.8A,C). In all four mice, the aortic outflow tract was also positioned cranially relative to the left component of the common atrioventricular junction (Figs9B and 10B). Such malalignment, or lack of wedging, was not seen in any of the developing mice with normal septal structures (Fig.7B).

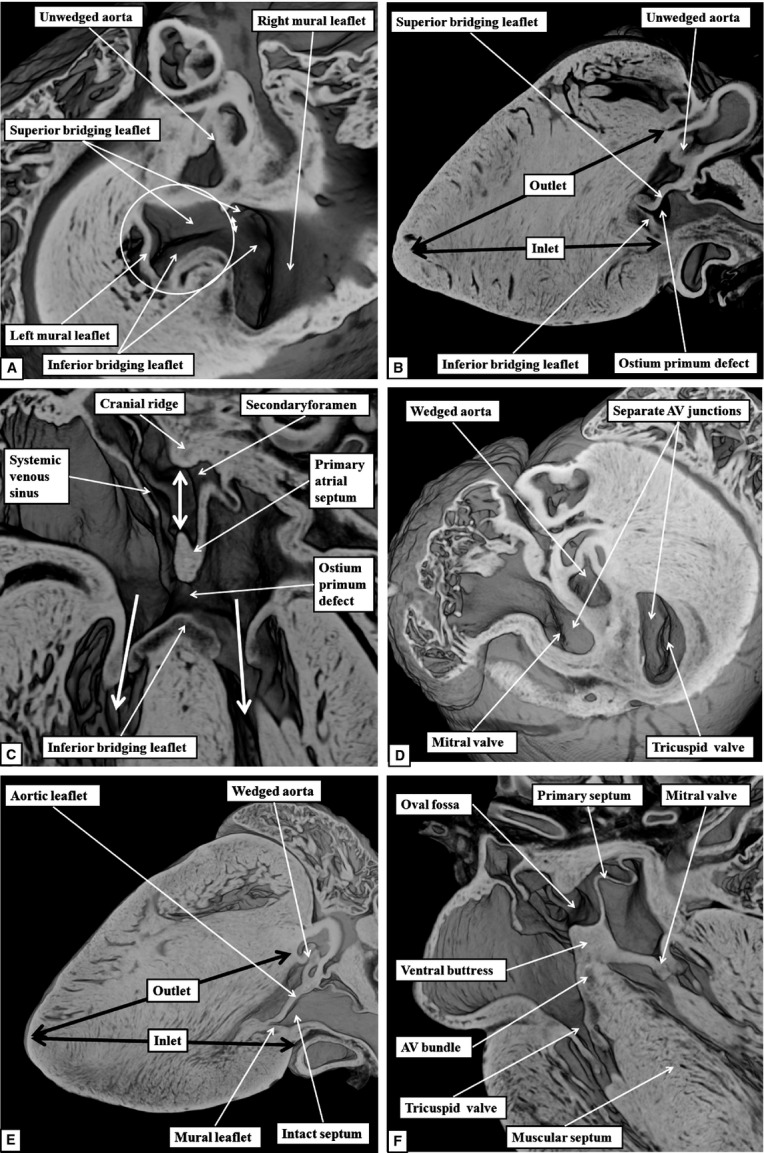

All four mice, therefore, exhibit the phenotypic features of atrioventricular septal defect with common atrioventricular junction. This is well appreciated when orthogonal sections taken through the embryo with the smallest defect (Fig.12A–C) are compared with orthogonal sections showing the features of normal septation (Fig.12D–F). The short axis plane in the abnormal heart shows the commonality of the atrioventricular junction, fusion of the bridging leaflets to each other producing separate valvar orifices for the right and left ventricles, with the left valve having an obvious trifoliate arrangement (Fig.12A). The short axis section also shows the unwedging of the aortic valve (Fig.12A). In the normal heart, as already emphasised (Fig.7B), the aortic root is wedged between the bifoliate mitral valve and the ventricular septum (Fig.12D). The long axis sagittal section reveals disproportion between the lengths of the inlet and outlet dimensions of the ventricular mass. This plane again confirms the unwedging of the aorta revealed in the short axis section (Fig.12B). The comparable section of the normal heart reveals a lesser degree of inlet–outlet disproportion, and shows the integrity of the septal components (Fig.12E). The long axis coronal section, or four-chamber section, then shows the virtually normal formation of the atrial septum itself in the hearts with ostium primum defects, with the protuberence on its leading edge presumably derived from the mesenchymal cap (Fig.12C). The section from the normal heart at this stage (Fig.12F), taken in the same plane as far as this can be arranged, shows the persisting muscular cranial ridge at the site of initial breakdown of the primary septum, and how the buttress derived from the vestibular spine, along with the mesenchymnal cap, anchors the primary septum itself to the separated atrioventricular junctions.

Fig 12.

The images compare the morphology of the normal septal components in the setting of separate atrioventricular (AV) junctions as seen in the three orthogonal planes (D–F) with the arrangement in the abnormal mice with ostium primum defects (A–C).

Discussion

The finding of four examples of mice with spontaneous dysmorphogenesis producing ostium primum defects amongst embryos from a wild-type outbred mouse line has permitted us to make direct comparisons with the morphological features of the normal heart at comparable stages of development. The ability to interrogate our episcopic datasets in any desired plane demonstrates unequivocally that, although the ostium primum defect produces shunting between the cardiac chambers at the atrial level, and hence is an inter-atrial communication, it is an atrioventricular, rather than an atrial, septal defect.

The images confirm that, as is now well established in clinical practice, the phenotypic feature of the ostium primum defect is the commonality of the atrioventricular junction, along with the unwedging of the subaortic outflow tract (Anderson et al. 2010). Development of the atrial septum itself can be virtually normal, as seen in one of our hearts where its leading edge extended caudally to the level of the atrioventricular junction. Shunting occurs at the atrial level because the bridging leaflets of the valve guarding the common atrioventricular junction are depressed into the ventricular cavity, and are firmly fused to the bowed crest of the muscular ventricular septum. It might be thought, therefore, that the muscular ventricular septum is itself deficient. Indeed, some authorities argue that there is separate formation during development of a ‘septum of the atrioventricular canal’ (Van Praagh et al. 1989; Geva, 2009). The location of the atrioventricular conduction axis on the ventricular septal crest, however, despite its abnormal configuration, suggests that, at least for the ventricular septum, this is not the case. Instead, the persistence of the common atrioventricular junction has prevented the normal fusion of the ventricular and atrial septal components, leaving the remaining part of the muscular septum with a bowed leading edge, the edge being concave towards the ventricular apex. The buttress of the atrial septum derived from the muscularised vestibular spine, in contrast, can justifiably be considered as an atrial component of a ‘canal septum’ (Geva, 2009).

The morphological findings in our mouse hearts replicate those shown previously in human hearts (Becker & Anderson, 1982; Penkoske et al. 1985). The phenotypic features of so-called atrioventricular canal defects, or atrioventricular septal defects with common atrioventricular junction, are just as ‘complete’ when there are separate valvar orifices for the right and left ventricles as when the junction is guarded by a valve with a solitary atrioventricular orifice. The aortic root, furthermore, is just as unwedged in the ostium primum defect as when there is a common atrioventricular valvar orifice. From the stance of anatomy, there is no justification for separating these lesions into purported ‘partial’ and ‘complete’ variants. The features usually distinguished by clinicians when using these terms reflect the level of shunting through the atrioventricular septal defect (Anderson et al. 2010).

The discovery of the mice with spontaneous dysmorphogenesis producing ostium primum defects adds further strength to the notion that the primary developmental fault lies in the atrioventricular canal itself, rather than in the endocardial cushions. The cushions are certainly the primordiums for formation of the valvar leaflets. It is also possible, of course, that they influence the development of the canal musculature. The very recognition in the ostium primum defect of a tongue of valvar tissue uniting the leaflets of the common valve that bridge the ventricular septum (Becker & Anderson, 1982), nonetheless, provides circumstantial evidence that the lesion is not due to failure of fusion of the cushions. Analysis of our mice adds further strength to the notion that the problem lies in inadequate formation of the vestibular spine (Webb et al. 1998; Blom et al. 2003) or the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion (Briggs et al. 2013). We have shown, as did Snarr et al. (2007), the normal growth of the vestibular spine from the pharyngeal mesenchyme through the right margin of the dorsal mesocardial connection. It is this process that cements the leading edge of the primary atrial septum to the insulating plane provided by the fused atrioventricular cushions. It also confines the pulmonary vein to the left atrium, with the relatively central location of the pulmonary venous orifice in one of our mice adding further strength to the notion that growth of the spine is a crucial element in normal septation.

This growth of extracardiac tissue into the atrial cavity was illustrated with exquisite accuracy by His in the latter part of the 19th century (His, 1885). His named the structure the ‘spina vestibuli’, which we, and others, have translated to vestibular spine. Its importance went unrecognised for over 100 years until Tasaka et al. (1996) resurrected interest in the structure. We then demonstrated its potential importance in the morphogenesis of hearts with common atrioventricular junction (Webb et al. 1997, 1998). It was its origin from the second heart field that was revealed by Snarr et al. (2007), although they chose to describe the structure as the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion, rather than the vestibular spine. Our preference is to retain the initial title provided by His in its anglicised version. Our episcopic datasets from the normally developing hearts show that, subsequent to the ventral growth of the spine, it then muscularises, together with the mesenchymal cap, to form the ventro-caudal buttress of the atrial septum. This is the basal component of the right atrial rim of the oval fossa. The cranial rim of the fossa is the ridge formed at the initial site of breakdown of the primary atrial septum. The caudal margin, at the dorsal hinge of the primary septum, is an infolding of the atrial walls between the interseptovalvar space of the right atrium and the pulmonary venous component of the left atrium.

A comparable account of the development of atrial septal morphology, denying the existence of growth from the atrial roof of a second septum, had already been provided by the end of the 19th century (Rose, 1889). The increasing length of the fold is provided by growth of the atrial walls enclosing it, rather than direct proliferation of a second septal structure into the atrial cavity. Despite the precedent provided by Rose (1889), popular textbooks of cardiac embryology still perpetuate the myth that a secondary septum grows down from the atrial roof to parallel the formation of the primary septum. It is deficiency of the primary atrial septum, which forms the floor of the oval fossa, that is responsible for so-called ‘secundum’ defects. The essence of the ‘primum defect’, in contrast, is the failure of secondary growth of the vestibular spine (Briggs et al. 2013). Whether such failure of growth of the vestibular spine underscores the morphogenesis of all variants of atrioventricular septal defect with common atrioventricular junction, however, has still to be established.

References

- Anderson RH, Wessels A, Vettukattil J. Morphology and morphogenesis of atrioventricular septal defect with common atrioventricular junction. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2010;1:59–67. doi: 10.1177/2150135109360813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RH, Spicer DE, Brown NA, et al. The development of septation in the four-chambered heart. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2014;297:1414–1429. doi: 10.1002/ar.22949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschoff L. Referat uber die Herzstorungen in ihren Beziehungen zu den Spezifischen Muskelsystem des Herzens. Verh Dtsch Pathol Ges. 1910;14:3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Becker AE, Anderson RH. Atrioventricular septal defects. What's in a name? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1982;83:461–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom NA, Ottenkamp J, Wenick ACG, et al. Deficiency of the vestibular spine in atrioventricular septal defects in human foetuses with Down syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:180–184. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs LE, Kakarla J, Wessels A. The pathogenesis of atrial and atrioventricular septal defects with special emphasis on the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion. Differentiation. 2012;84:117–130. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs LE, Phelps AL, Brown E, et al. Expression of the BMP receptor Alk3 in the second heart field is essential for development of the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion and atrioventricular septation. Circ Res. 2013;112:1420–1432. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.300821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geva T. Anomalies of the atrial septum. In: Lai M, Mertens L, Cohen M, Geva T, editors. Echocardiography in Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease: From Fetus to Adult. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. p. 158. [Google Scholar]

- His W. In: Anatomie Menschlicher Embryonen. His W, editor. Leipzig: Zür Geschichte der Organe, Vogel; 1885. pp. 129–184. Vol. 3. ( ) ) [Google Scholar]

- Mohun TJ, Weninger WJ. Imaging heart development using high-resolution episcopic microscopy. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2011;21:573–578. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mönckeberg JG. Beitrage zur normalen und pathologischen Anatomie des Herzens. Verh Dtsch Pathol Ges. 1910;14:64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Odgers PNB. The development of the pars membranacea septi in the human heart. J Anat. 1937;72:247–259. /38) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock TB. Malformation of the heart consisting in an imperfection of the auricular and ventricular septa. Trans Pathol Soc London. 1846;1:61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Penkoske PA, Neches WH, Anderson RH, et al. Further observations on the morphology of atrioventricular septal defects. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1985;90:611–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose C. Zue entwickelungsgeschichte des Saugetierherzens. 1889;15:436–456. Morphol Jahrb. [Google Scholar]

- Snarr BS, O'Neal JL, Chintalapudi MR, et al. Isl1 expression at the venous pole identifies a novel role for the second heart field in cardiac development. Circ Res. 2007;101:971–974. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.162206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasaka H, Krug EL, Markwald RR. Origin of the pulmonary venous orifice in the mouse and its relation to the morphogenesis of the sinus venosus, extracardiac mesenchyme (spina vestibule), and atrium. Anat Rec. 1996;246:107–113. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199609)246:1<107::AID-AR12>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Mierop LHS, Alley RO, Kansel HW, et al. The anatomy and embryology of endocardial cushion defects. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1962;43:71–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Praagh R, Geva T, Kreutzer J. Ventricular septal defects: how shall we describe, name and classify them? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;14:1298–1299. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90431-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Rokitansky CF. Die defecte der Scheidewande des Herzens. Pathologisch-Anatomische Abhandlung. Wien: Wilhelm Braumuller; 1875. p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Webb S, Brown NA, Anderson RH. Cardiac morphology at late fetal stages in the mouse with trisomy 16: consequences for different formation of the atrioventricular junction when compared to humans with trisomy 21. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;34:515–524. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb S, Brown NA, Anderson RH. Formation of the atrioventricular septal structures in the normal mouse. Circ Res. 1998;82:645–656. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.6.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]