Abstract

This study describes a unique assessment of primate intrinsic foot joint kinematics based upon bone pin rigid cluster tracking. It challenges the assumption that human evolution resulted in a reduction of midfoot flexibility, which has been identified in other primates as the “midtarsal break.” Rigid cluster pins were inserted into the foot bones of human, chimpanzee, baboon and macaque cadavers. The positions of these bone pins were monitored during a plantarflexion-dorsiflexion movement cycle. Analysis resolved flexion-extension movement patterns and the associated orientation of rotational axes for the talonavicular, calcaneocuboid and lateral cubometatarsal joints. Results show that midfoot flexibility occurs primarily at the talonavicular and cubometatarsal joints. The rotational magnitudes are roughly similar between humans and chimps. There is also a similarity among evaluated primates in the observed rotations of the lateral cubometatarsal joint, but there was much greater rotation observed for the talonavicular joint, which may serve to differentiate monkeys from the hominines. It appears that the capability for a midtarsal break is present within the human foot. A consideration of the joint axes shows that the medial and lateral joints have opposing orientations, which has been associated with a rigid locking mechanism in the human foot. However, the potential for this same mechanism also appears in the chimpanzee foot. These findings demonstrate a functional similarity within the midfoot of the hominines. Therefore, the kinematic capabilities and restrictions for the skeletal linkages of the human foot may not be as unique as has been previously suggested.

Keywords: Midtarsal Break, Comparative Biomechanics, Bone Pins, Longitudinal Arch, Foot Evolution

INTRODUCTION

Discussion of the “midtarsal break” as a distinguishing feature of the non-human primate foot has gained some currency in recent years. This break typically describes an event during stance phase of the locomotor cycle where the midfoot dorsiflexes in a way that lifts the heel off the substrate before the forefoot begins to rise. Events that fit this description are commonly observed in the feet of non-human primates (Elftman & Manter, 1935a; Bojsen-Møller, 1979; Lewis, 1980; Susman, 1983; Gebo, 1992; D’Août, et al., 2002; Vereecke et al., 2003; D’Août & Aerts, 2008; Vereecke & Aerts 2008). The development of a longitudinal arch within the human foot is thought to have resulted in a loss of this midfoot flexibility so that humans no longer display appreciable levels of midfoot dorsiflexion. However, a great deal of research of the human foot also describes a compliance of the human longitudinal arch (Hicks, 1953; Sammarco & Hockenbury, 2001; Erdemir, et al. 2004; Vereecke & Aerts, 2008; Caravaggi, et al. 2010). This compliance is effectively also a midfoot dorsiflexion that occurs during mid-stance phase. Although the human arch compliance does not typically raise the heel in the same fashion as the non-human primate midtarsal break, from the perspective of midtarsal joint kinematics the two movements would seem to be similar. This association has been recognized before although the human motion is presumed to be smaller and produced by an accumulation of minute actions within the various intertarsal and tarsometatarsal joints (Hicks, 1954; Stern & Susman, 1983; Berillon, 2003; Ward, et al. 2011). Thus, the conventional wisdom claims that the non-human primate midfoot dorsiflexes more than that of the human and that skeletal morphologies can be identified which are associated with this functional difference.

In this paper we investigate midfoot flexibility in the primate foot. Presumably the kinematics of the human midfoot can be seen as a natural extension of the basic primate pattern. By investigating foot kinematics under controlled experimental conditions, we evaluate the validity of that presumption. We therefore evaluate the null hypothesis that the plantarflexion-dorsiflexion kinematics of the midtarsal (talonavicular, calcaneocuboid and lateral cubometatarsal) joints do not differ within the investigated primate genera (Homo, Pan, Papio and Macaca). This kinematic analysis is conducted so as to explore not just the rotational movement patterns that produce midfoot flexion, but also the orientations of the specific rotational axes associated with those movements. This refinement adds a new dimension to the investigation of primate joint kinematics. Armed with these additional data, we seek to identify some of the kinematic distinctiveness within each of the investigated primate feet.

METHODS

This analysis is based upon an in vitro assessment of leg and foot specimens drawn from 18 humans (Homo), 4 chimpanzees (Pan), 5 baboons (Papio) and 2 macaques (Macaca). Difficulties associated with obtaining the non-human specimens, particularly chimpanzees, mean that the non-human primate sample size of our study was small and therefore may not fully appreciate non-human primate biological variability. The small body size of macaques greatly increased data collection difficulties and so we were only able to collect data from two individuals. Nevertheless, our non-human primate sample sizes are comparable to those associated with human cadaver based studies (e.g., Bojsen-Møller, 1979; Gomberg, 1985; Ouzounian & Shereff, 1989; Blackwood, et al. 2005; Nester, et. Al 2007; DeSilva, 2010; Nowak, et al. 2010).

The human specimens were obtained through state run donation programs for anatomical education and research and therefore represent a geriatric population. The human cadavers come to our laboratory pre-embalmed with a solution of 50% ethyl alcohol, 25% water, 25% glycerin and 5% formaldehyde by volume. These cadavers were first used in a dissection based human anatomy course. Foot anatomy is the last item investigated within this course, and to prevent desiccation the subject’s feet and legs were kept tightly wrapped in plastic at all times except when under direct examination by the students. To further inhibit desiccation during dissections, the specimens were also frequently sprayed with a solution of 50% water, 20% ethyl alcohol and 30% propylene glycol by volume. The non-human primate specimens were obtained from various biomedical research facilities and, when living, were all used in unrelated research projects at those facilities. The lower limbs were harvested from the donor animal after necropsy, which was typically performed within 24 hours of death. These specimens were not embalmed and were frozen for shipment to our laboratory.

Each specimen was prepared for kinematic investigation by the complete removal of almost all muscle, skin, nerve and vascular tissue, leaving only ligaments to maintain joint integrity. This form of specimen preparation is similar to that used by other kinematics researchers (e.g., Ouzounian & Shereff, 1989; Blackwood, et al. 2005). The specimens, both human and non-human, were then immersed for at least seven days in a solution of 50% water, 20% ethyl alcohol, 25% propylene glycol and 10% formaldehyde by volume. Although ligaments are not generally subject to formalin induced contraction (Tan, et al. 2002; Jaung, et al. 2011), the soak in this fluid was intended to replicate similar levels of fixation for each specimen. In both the human and non-human primate specimens, because they possessed no relevant muscle tissue, the resulting condition was considered to represent a more mobile foot relative to the living analog.

Intrinsic foot joint motion was evaluated using rigid body cluster modeling. Four infrared emitting diodes (IRED) were mounted onto a stiff cardboard backing to create each cluster. Each cluster was attached to a two pronged pin constructed from stiff 16 gage wire. The two prongs of the pins were then inserted into their respective bones (tibia, calcaneus, talus, cuboid, navicular and fifth metatarsal) and fixed using a water activated and water proof polyurethane adhesive (Gorilla Glue®, The Gorilla Glue Company). After pin insertion, the adhesive was allowed to set by returning the specimens to their fluid bath for at least 24 additional hours. The IRED clusters were secured to the pins, using a screw and bolt, just prior to data collection. This bone pin construction and attachment protocol was evaluated to insure that the pins remained secure and unmoving relative to their specific bones during the data collection process.

During kinematic data collection each specimen was situated so that its second and third toes were secured to a horizontal surface to replicate a ground stable foot position during stance phase that might be associated with a weight bearing limb. A starting reference position was defined with the tibia held perpendicular to the horizontal surface; the foot was permitted to assume its own posture relative to this tibial positioning. This choice of reference position meant that the non-human primate feet, particularly the chimpanzee feet, adopted a more inverted posture when compared to the human feet. Cluster orientations recorded from this reference posture represent the zero rotational position for each joint. Anatomical reference planes were defined for each subject so that a line passing from the superior aspect of the calcaneal tuberosity through the center of the head of the second metatarsal served as the posterior-anterior axis; a line passing through the midpoint of the medial and lateral malleoli to the midpoint of the medial and lateral tibial condyles represented the inferior-superior axis; and the vector cross product of these two anatomically established referent axes established the medial-lateral axis.

Experimental movement was produced by having one researcher (TMG) cycle the leg forward and backward over the foot within the sagittal plane for thirty seconds – producing about thirty cycles. Primary data consisted of recording the changing XYZ coordinate positions of each IRED within the bone pin clusters during this plantarflexion-dorsiflexion-plantarflexion cycle using an Optotrak® 3020 (Northern Digital Inc) operating at 30 Hz.

Following the methods described by Ball and Pierrynowski (1996), for each data frame the XYZ coordinates of each IRED was recorded as a three element column vector. The four IRED vectors that form a cluster were combined to form a 3×4 matrix. Each matrix was normalized by subtracting its centroid vector. The matrix associated with the static control position was designated Pc and the same cluster observed during data frame [i] of the motion data collection was designated as Po[i]. The differences between matrices were calculated as M[i] = Pc Po[i]T. The resulting 3×3 matrix M was submitted to singular value decomposition, so that M = U Σ VT. Combining two of these decomposed values yields R = U VT; where R is an orthonormal rotation matrix that describes the orientation of a bone cluster. The rotation matrices that represent the two bones of each joint were combined, for example J[i]calcaneocuboid = R[i]calcaneusT R[i]cuboid, to yield a sequence of rotation matrices J[i] that describe the observed rotational movements of the calcaneocuboid joint relative to the observed starting position. This process was repeated to create matrix sequences that describe observed rotational motions at the tibiotalar, calcaneocuboid, talonavicular, and the lateral cubometatarsal joints. The tibia cluster was evaluated by itself within the anatomical reference frame to derive statements of leg (tibia) movement during data collection.

The Functional Alignment technique (Ball and Greiner, 2012) was used to further refine the observed data. Axis alignment matrices (BA and MA) were calculated for each segment component of a joint. These values were used to refine the description of joint rotation as: F[i] = BAT J[i] MA. The F[i] rotation matrix sequence describes the rotational pattern observed to occur about the functional, natural, rotational axis of the joint. The BA and MA matrices, derived individually for each joint from the application of the Functional Alignment procedure, contain the orientation of the joint’s rotational axis relative to the anatomical reference planes. While the rotational axis expressed from the perspectives of both the proximal segment (BA base segment matrix) and the distal segment (MA move segment matrix) are required to properly calculate functional movement patterns, the two expressions tend to be very similar. To avoid the appearance of redundancy within this presentation, rotational axis orientations from only the proximal (base) segments are reported.

The movement cycle for each subject was defined by the angular position of the tibia cluster. To provide uniformity of comparison among subjects, this cycle was summarized as a percentage of the observed movement, with 0% representing full plantarflexion, 50% as full dorsiflexion and 100% returning to full plantarflexion. This cycle was then broken down into fifty time steps. For each subject, a spatial average (Ball and Pierrynowski, 1996; Ball and Greiner, 2012) of the F[i] rotation matrices associated with each two-percentile step was calculated. Then each average rotation matrix was subjected to Cardan angle decomposition to derive a simultaneous assessment about three rotational axes. The reported data focus solely upon rotations that occur about the predominantly medial-lateral directed axes, thus limiting the presentation to midfoot rotations that might best be described as flexion-extension. Rotational positions are plotted against the percentage of the driving motion cycle to reveal the pattern of intrinsic foot joint rotations as a product of leg plantarflexion-dorsiflexion.

The driving motion roughly replicated talocrural plantarflexion-dorsiflexion but the forward movement of the leg was continued until the heel was lifted off the surface and additional foot joint movement was halted by ligamentous restrictions. The arc excursion of the tibia (leg) typically extended about 20 degrees beyond the limits of dorsiflexion at the talocrural joint (See Table 1). Although the driving motion was intended to be restricted to the sagittal plane, the manual control of the specimen did inadvertently produce some coronal and transverse plane motion (See Table 1). An advantage of using the Functional Alignment procedure is that it accounts for these out-of-plane motions by permitting a focus onto the medial-lateral referenced axis. Therefore, the influence of these small out-of-plane inputs would have been minimized.

Table 1.

Description of the experimental driving motion. The experimental driving motion was evaluated as the arc of excursion shown by the tibia within the laboratory reference frame. The primary driving motion was considered to occur within the sagittal plane. Excursions in the coronal and transverse planes are regarded as experimental error due to the manual input of the driving motion. The talocrural arc depicts the conventional appreciation of the input motion as a plantarflexion-dorsiflexion of the leg upon the ankle. The tibial arc associated with heel-off is evaluated as the difference between the arc of tibial excursion in the sagittal plane and the plantarflexion-dorsiflexion arc at the talocrural joint. This value represents the additional driving motion that lifted the heel and potentially contributed to midfoot motion. All angular values are presented in degrees.

| Genus | Homo | Pan | Papio | Macaca | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | 18 | 4 | 5 | 2 | ||

| Tibial Excursion |

Sagittal Plane Arc |

Mean | 75.4 | 97.5 | 106.0 | 102.5 |

| Minimum | 60 | 90 | 90 | 95 | ||

| Maximum | 105 | 110 | 120 | 110 | ||

| Coronal Plane Arc |

Mean | 3.9 | 3.0 | 5.2 | 5.0 | |

| Minimum | 0 | 2 | 4 | 4 | ||

| Maximum | 7 | 4 | 8 | 6 | ||

| Transverse Plane Arc |

Mean | 3.6 | 3.8 | 4.8 | 7.0 | |

| Minimum | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Maximum | 7 | 4 | 8 | 9 | ||

| Mean Talocrural Plantarflexion-Dorsiflexion Arc | 57.1 | 76.3 | 85.0 | 72.5 | ||

| Mean Tibial Arc Associated with Heel-Off | 18.3 | 21.3 | 21.0 | 30.0 | ||

After data collection, each subject was fully skeletonized so that the individual bones could be inspected. This allowed for an assessment of degenerative changes in the joint surfaces and an assessment of age based upon the epiphyseal fusion in the available bones. Although we employed human subjects drawn from a geriatric population, none of the human specimens retained for this analysis demonstrated any obvious degeneration of their joint surfaces. A pre-selection of human subjects rejected all potential specimens with extreme conditions of hallux valgus or muscular wasting. The examination of the bones from the non-human primates showed that they were all fully adult based on complete epiphyseal fusion, and that no specimen was associated with any obvious degenerative joint pathology.

A similar kinematic study conducted by Ouzounian and Shereff (1989) found that bone pin placement could be problematic, even for presumed foot anatomy experts. The complete skeletonizing of the specimens allowed us to verify bone pin placement. Subjects were excluded from the study when a bone pin was found to be incorrectly placed. Because of this process, we are in the unique position of being confident in the correct placement, and continued secure attachment, of the bone pins for our entire kinematic sample.

RESULTS

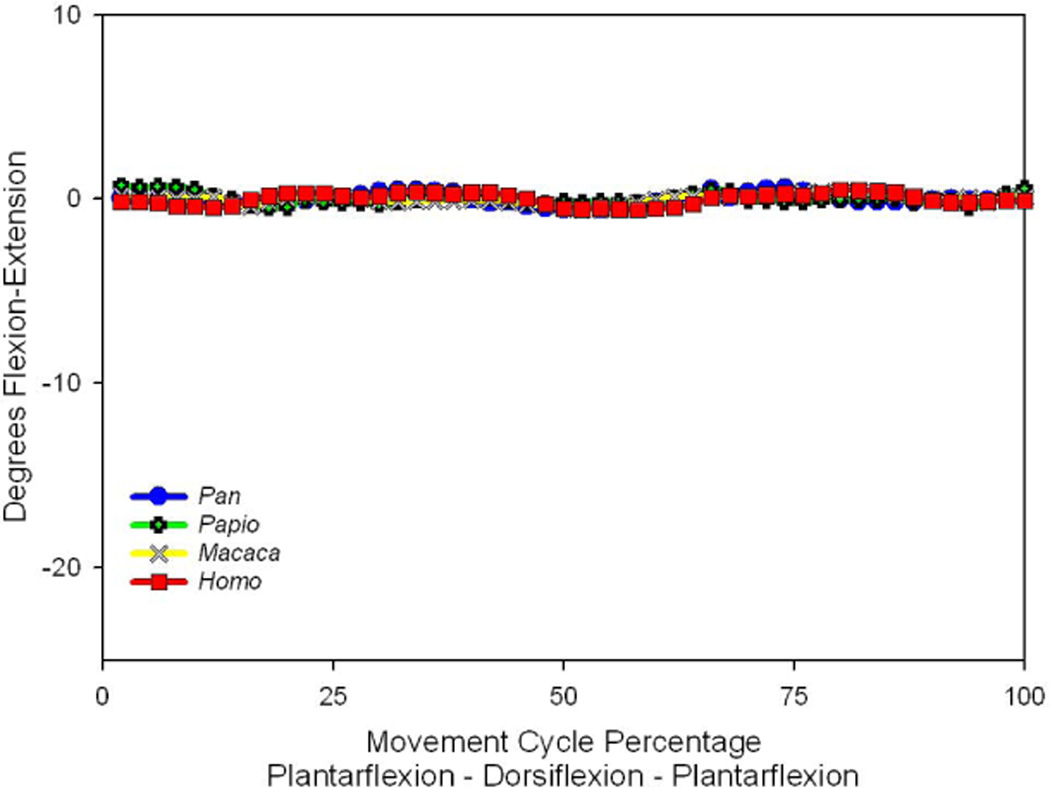

Presentations of rotational movements must be considered in association with the orientation of their rotational axes (Greiner and Ball, 2009). These data are presented together (See Tables 2 and 3) in summary form for each subject examined for this study. The human values provided here, and the relative magnitudes of joint mobility, compare well with some published reports (Ouzounian and Shereff, 1989; Cornwall, et al. 1999; Blackwood, et al. 2005; Wolf, et al 2008). For all specimens, the calcaneocuboid joint demonstrated little midfoot flexibility. When considered as an average for each genus (Fig. 1) this joint displayed motion patterns that had no obvious relationship to the plantarflexion-dorsiflexion driving motion and appeared to be almost immobile. This finding is indistinguishable from data noise, and therefore justified the exclusion of calcaneocuboid joint motion results from the rest of this presentation.

Table 2.

Rotational axis orientations and range of flexion-extension rotations observed for the human subjects within this study. Axis orientations are presented as plane projection (Ball and Greiner, 2008) deviations from the medial-lateral anatomical axis. All values are presented in degrees.

| Subject | Sex | Age | Calcaneocuboid Joint | Lateral Cubometatarsal Joint | Talonavicular Joint | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axis Orientation | Range of Motion |

Axis Orientation | Range of Motion |

Axis Orientation | Range of Motion |

||||||

| Transverse Plane Projection |

Coronal Plane Projection |

Transverse Plane Projection |

Coronal Plane Projection |

Transverse Plane Projection |

Coronal Plane Projection |

||||||

| Homo 1 | M | 69 | −15 | 30 | 0.6 | −7 | 24 | 8.3 | −24 | 31 | 1.0 |

| Homo 2 | M | 71 | 37 | 0 | 2.2 | 21 | −28 | 5.8 | −3 | −49 | 18.3 |

| Homo 3 | M | 86 | −16 | 28 | 2.2 | 35 | 18 | 7.0 | 27 | 15 | 4.7 |

| Homo 4 | F | 86 | −14 | −25 | 0.8 | −7 | 30 | 3.3 | −12 | 16 | 2.3 |

| Homo 5 | F | 92 | 24 | 23 | 2.0 | −26 | 11 | 4.1 | −15 | −45 | 3.2 |

| Homo 6 | F | 80 | 11 | 30 | 1.5 | 18 | −46 | 1.9 | −8 | −35 | 16.7 |

| Homo 7 | F | 94 | −8 | 37 | 2.1 | 1 | 29 | 4.6 | −50 | −38 | 1.9 |

| Homo 8 | F | 87 | −33 | 26 | 0.9 | 36 | −22 | 5.0 | −14 | −15 | 2.9 |

| Homo 9 | F | 77 | 36 | 27 | 1.3 | 24 | 30 | 7.7 | 11 | 34 | 1.2 |

| Homo 10 | F | 86 | 17 | 31 | 5.0 | 56 | −34 | 1.2 | 14 | 24 | 6.8 |

| Homo 11 | M | 77 | −20 | −38 | 1.1 | −18 | 17 | 7.0 | −9 | 3 | 2.1 |

| Homo 12 | M | 88 | −2 | 16 | 2.4 | 9 | 24 | 6.3 | 6 | −3 | 5.3 |

| Homo 13 | F | 98 | 10 | 7 | 2.3 | 28 | 9 | 6.6 | 10 | −17 | 5.5 |

| Homo 14 | M | 78 | 5 | 2 | 3.1 | −28 | 3 | 5.2 | 16 | 9 | 0.8 |

| Homo 15 | F | 84 | −13 | −41 | 3.8 | 1 | 15 | 6.7 | −4 | 7 | 2.3 |

| Homo 16 | F | 80 | 28 | −5 | 3.1 | 0 | 16 | 4.4 | 21 | 10 | 1.2 |

| Homo 17 | M | 88 | −24 | 19 | 1.0 | −65 | 3 | 13.6 | −2 | −16 | 1.0 |

| Homo 18 | F | 70 | −6 | 30 | 0.7 | −59 | 1 | 11.6 | 19 | −36 | 2.1 |

Table 3.

Rotational axis orientations and range of flexion-extension rotations observed for the non-human subjects within this study. The same conventions apply as described for Table 2.

| Subject | Sex | Age | Calcaneocuboid Joint | Lateral Cubometatarsal Joint | Talonavicular Joint | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axis Orientation | Range of Motion |

Axis Orientation | Range of Motion |

Axis Orientation | Range of Motion |

||||||

| Transverse Plane Projection |

Coronal Plane Projection |

Transverse Plane Projection |

Coronal Plane Projection |

Transverse Plane Projection |

Coronal Plane Projection |

||||||

| Pan 1 | M | 20 | −15 | −28 | 1.3 | −34 | 8 | 9.4 | 21 | 22 | 4.6 |

| Pan 2 | M | 11 | −11 | −66 | 0.3 | 11 | 21 | 6.5 | 35 | −30 | 3.9 |

| Pan 3 | M | 19 | −13 | 11 | 2.6 | 6 | 26 | 3.9 | 35 | 5 | 3.6 |

| Pan 4 | F | 19 | 23 | 9 | 6.6 | −35 | 1 | 16.3 | 35 | −3 | 3.8 |

| Papio 1 | F | * | 47 | 10 | 1.4 | * | * | * | 1 | 34 | 3.8 |

| Papio 2 | M | * | 86 | 4 | 0.7 | * | * | * | −8 | 29 | 11.9 |

| Papio 3 | F | * | −28 | 16 | 0.7 | * | * | * | 2 | 22 | 5.4 |

| Papio 4 | F | 8 | −35 | 8 | 1.0 | * | * | * | --8 | 17 | 1.3 |

| Papio 5 | F | 10 | −30 | −35 | 3.9 | −11 | −15 | 4.0 | −12 | 13 | 8.4 |

| Macaca 1 | F | 19 | −1 | 11 | 1.2 | * | * | * | 26 | −6 | 3.8 |

| Macaca 2 | F | 12 | −35 | 17 | 4.1 | * | * | * | −5 | 10 | 9.5 |

An asterisk (*) denotes missing data for this subject.

Figure 1.

The average flexion-extension rotations at the calcaneocuboid joint in the four evaluated primates. Positive rotations indicate joint flexion, while negative values are associated with extension. The joint motion identified during the driving plantarflexion-dorsiflexion cycle is essentially zero in all primate feet.

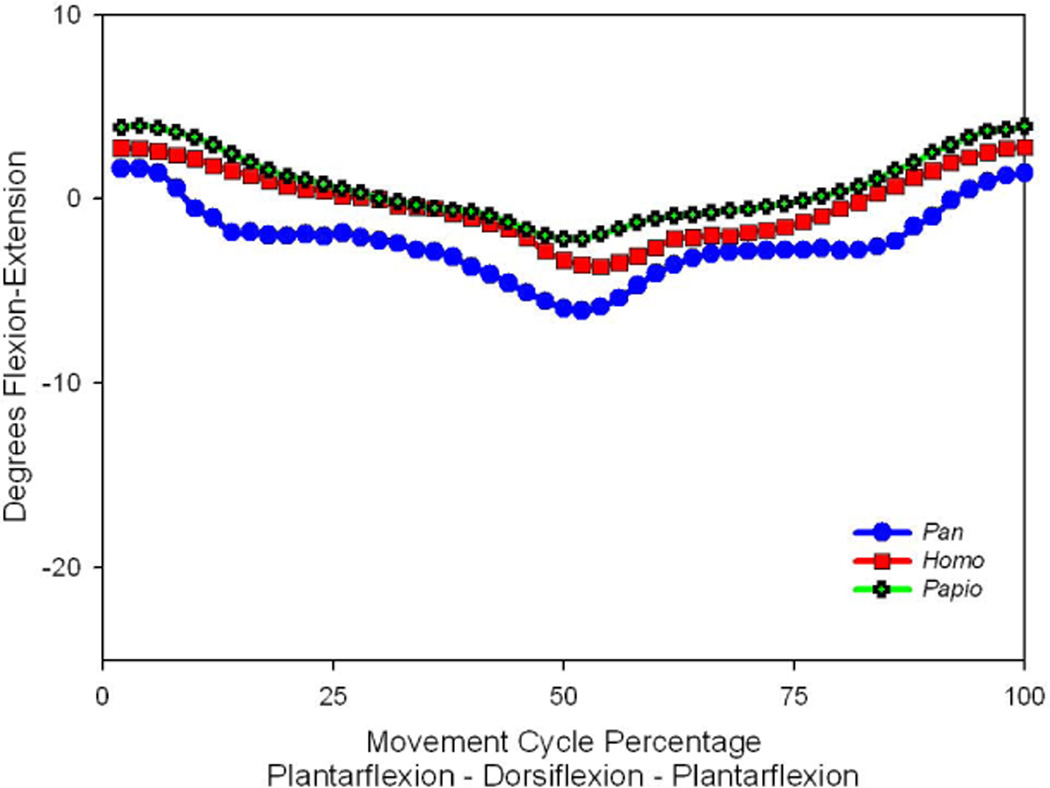

The lateral cubometatarsal (cuboid to fifth metatarsal) joint was shown to display appreciable mobility. The revealed average motion patterns (Fig 2) show roughly parallel motion curves and magnitudes of motion for the analyzed primates. Inspection of the average motion patterns suggest that the differences among the three presented primates are more due to differences of initial starting positions than to the magnitude of motion. However, these average plots do not coincide with the conventional (univariate) notion of the “arithmetic mean” as the orientations of all joint axes are not the same. Still, the motion patterns demonstrate general agreement among the three primates and, inasmuch as differences are exposed, the human foot represents a motion pattern that is between that of the ape and the monkey.

Figure 2.

The average flexion-extension rotations at the lateral cubometatarsal joint in three primates. Positive rotations indicate joint flexion, while negative values are associated with extension. The magnitudes of motion differ slightly among these genera, but the general pattern of motion appears similar.

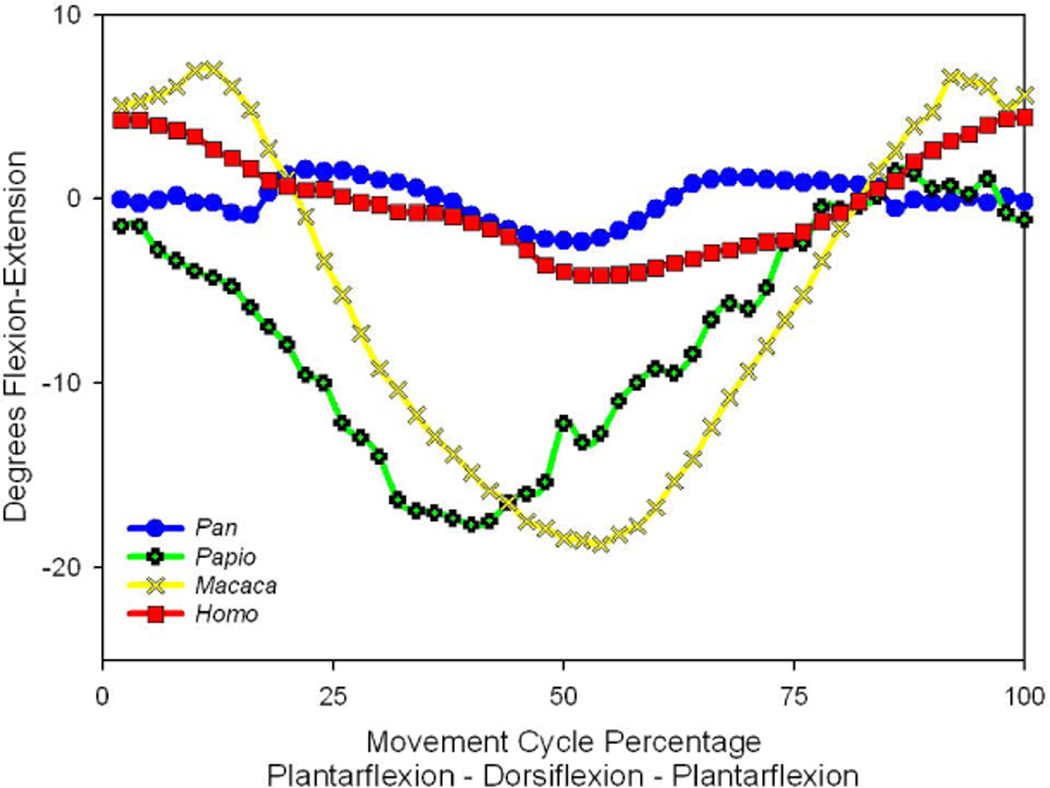

Midfoot flexibility for the medial side of the foot was revealed by the motion patterns of the talonavicular joint (See Fig 3). For this joint, a clear distinction appears between the flexibility patterns of the hominines (Homo and Pan) and the cercopithecines (Papio and Macaca). The two monkey genera demonstrate much greater mobility, while the hominines are more similar to each other and display a more rigid medial midfoot. This separation implies a phylogenetic divide in the function of the primate foot, although the possibility of a dramatic allometric shift cannot yet be dismissed.

Figure 3.

The average flexion-extension rotations at the talonavicular joint in the four evaluated primates. Positive rotations indicate joint flexion, while negative values are associated with extension. While mobility is seen in all primates, these patterns appear to clearly separate the highly mobile monkeys from the less mobile hominines.

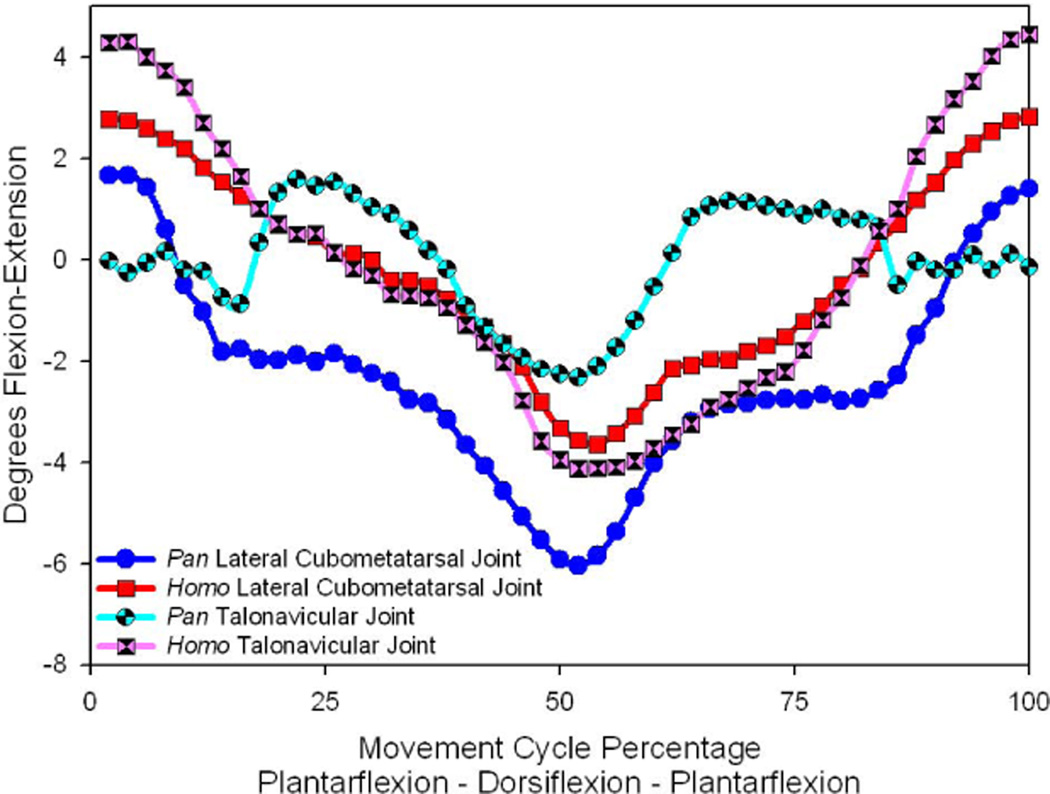

The apparent similarity of lateral cubometatarsal and talonavicular motions in Homo and Pan suggest that these joints may function together to provide midfoot flexion in the hominine foot. An exploration of this possibility is presented by an overlay comparison of hominine foot motion patterns within these two joints (See Fig. 4). The presentation of these patterns illustrates a very strong congruence between these two joints for humans; the average motion plots are nearly identical. There is a seemingly larger difference between the two joint motion patterns for chimpanzees. Closer examination shows that most of these differences lie in the extreme plantarflexed postures. If one focuses on the motion patterns from 25% to 75% of the motion cycle (essentially neutral posture to full dorsiflexion and back) the motion patterns of the two joints are more parallel. Similarly, the magnitude of motion within these ranges is about 4° for both joints (2° to −2° for the talonavicular joint and −2° to −6° for the lateral cubometatarsal joint). While humans do not show the same disparity between the joints during extreme plantarflexion, when the movement cycle for the human data are equally restricted, a similar 4° range of motion is revealed for both joints. These plots seem to indicate that the main difference between humans and chimpanzees in the kinematic behavior of the talonavicular joint occurs at the extremes of plantarflexion. This is a portion of the driving movement cycle that would not be typically associated with bipedal terrestrial locomotor behavior, but it may be associated with a reaching prehensile capability in the chimpanzee. When restricting the perspective to portions of the driving cycle that might be associated with bipedal locomotion, the results might be seen to suggest that there is little practical difference in the midfoot flexibility of the human and non-human hominine.

Figure 4.

A comparison of the average flexion-extension rotations for the two joints that would produce midfoot flexibility for Pan and Homo. Inasmuch as these motions evaluate the flexibility of the “transverse tarsal joint,” the average foot for Homo demonstrates a fairly uniform pattern for these joints of the medial and lateral foot. Pan, however, shows a less unified pattern, with less mobility noted for the medial foot’s talonavicular joint.

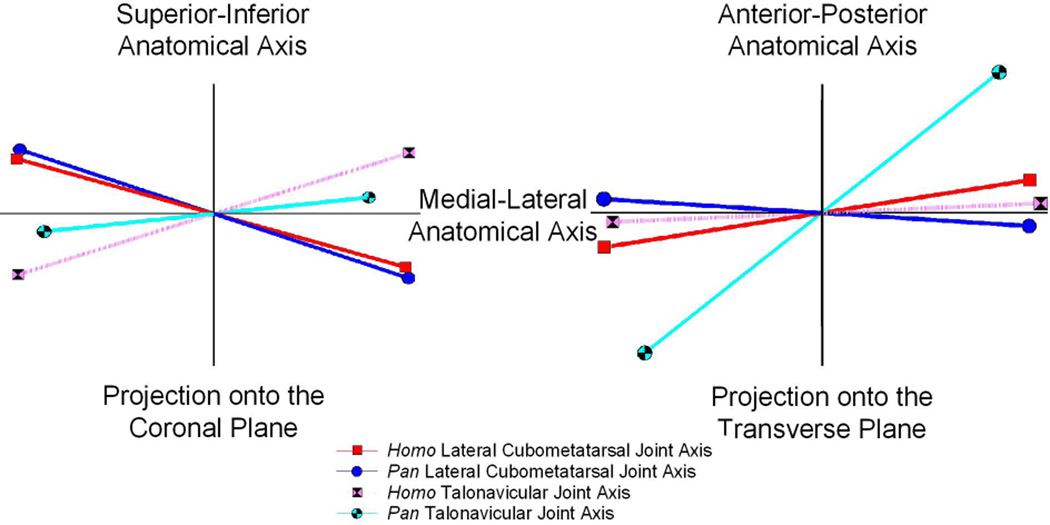

Although there may appear to be a basic similarity in the midfoot rotational motion patterns for Homo and Pan, an examination of the joint axis orientations (Figs 5) shows that important differences remain. The orientation of the human and chimpanzee lateral cubometatarsal joint axes appear to be fairly similar. Superior-inferior deviations of the lateral cubometatarsal joint axes are almost the same. The apparent differences shown for the anterior-posterior deviations of the axes are larger, but the difference between the orientations is still relatively small. It would appear that the lateral cubometatarsal joints of the two hominine genera respond to the plantarflexion-dorsiflexion driving motion in fundamentally the same way. The same cannot be said for the talonavicular joints. The rotational axis of the human talonavicular joint axis is more superior-inferior tilted than that of the chimpanzee, perhaps a feature of the human medial longitudinal arch. The same joint axis in chimpanzee shows a strong anterior-posterior tilt. This tilt orients the joint axis almost halfway between the anterior-posterior and medial-lateral anatomical planes, which suggest that the revealed motion patterns are almost as much adduction-abduction rotations as they are flexion-extension rotations. When joint axis orientations are considered the only revealed “similarity” between the human and chimpanzee foot is that the medial and lateral joints operate in different ways for both genera. Nevertheless, the lack of congruity between the orientations of the rotational axes suggests a dynamic mechanism for altering overall foot rigidity during the plantarflexion-dorsiflexion cycle for both humans and chimpanzees.

Figure 5.

Two composite projections of the rotational axis orientations for the lateral cubometarsal and talonavicular joints of Pan and Homo. The presentation on the left depicts axis orientations as projected onto the coronal plane, as if looking at the axes from a heel to toe perspective. The right side shows the axis orientations as projected onto the transverse plane, as if looking at the axes from above the foot. In all cases the joint rotational axes are somewhat oblique to the anatomical medial-lateral axis that is conventionally associated with the flexion-extension motion.

DISCUSSION

This study provides a unique assessment of intrinsic foot joint kinematics in primates derived from rigid body bone pin tracking. This is one of the few comparative kinematic studies where humans and non-human primates were evaluated using the same methods. Thus, we avoid some of the complications associated with interpreting comparative data derived from varying kinematic methods (Greiner, 2013). As with all kinematic studies, it can be important to clarify terms and definitions as used within the discussion. For this presentation, we equate the midtarsal region of the foot with the three joints we have investigated: the talonavicular, the calcaneocuboid and the lateral cubometatarsal joints. Midtarsal flexibility is evaluated as the combined flexion-extension response of these midtarsal joints, which approximates motion often described as the midtarsal break or the compliance of the longitudinal foot arches. Because midfoot flexibility is commonly observed to occur within a laboratory defined sagittal plane, our evaluation of these joints is limited to their response about the rotational axis that is most nearly aligned to the medial-lateral anatomical axis of the foot. The data collection methods used in this study evaluated motion for the joints with six degrees-of-freedom. Yet, we present data for only flexion-extension rotation because that is the motion that most closely approximates the activity associated with midtarsal flexibility. By making these clarifications, we do not mean to imply that flexion-extension is the only, or even the largest, motion produced by the plantarflexion-dorsiflexion driving action. Motions associated with some of the other five degrees of freedom for each joint can be substantial (Greiner 2012; Greiner & Ball 2008a; 2008b; 2010) and are therefore important for developing a more complete understanding of the foot’s function. By conducting a three-dimensional analysis we distinguish among the several motions associated with a joint but focus here only on the flexion-extension action that directly contributes to midfoot flexibility.

The comparisons of mobility at the calcaneocuboid joint and the lateral cubometatarsal joint (Figs. 1 and 2) show that greater flexion-extension mobility occurs at the more distal joint. This pattern applies equally to human and non-human primate feet. These data appear to support the more recent interpretations (D’Août, et al. 2002; Vereecke et al 2003; Greiner & Ball 2008a; 2008b; 2010; DeSilva, 2010; Bates 2013) and may serve to contradict the long standing supposition that a unique reduction of calcaneocuboid joint motion is the key to lateral longitudinal arch stability in the human foot (Elftman, 1960; Bojsen-Møller, 1979; Ouzounian & Shereff, 1989; Gebo, 1992; Meldrum, 2004). These results also provide kinematic evidence that demonstrate comparable levels of midfoot flexibility in both human and non-human primate feet, which was suspected by several authors (Crompton, et al. 2010; 2012; DeSilva & Gill, 2013). An examination of motion values for individuals (see Homo 17 and Homo 18 in Table 2) confirms the suggestion (Crompton, et al. 2010; Bates, et al. 2013) that some humans possess higher “ape-like” values for lateral foot flexibility. However, a further examination of individuals (see Pan 2, Pan 3 and Papio 5 in Table 3) shows that some non-human primates also possess the lower “human like” values.

An examination of the average kinematic patterns shows an intriguing clustering among the examined genera. The patterns of motion in the lateral cubometatarsal joint (Fig. 2) are essentially indistinguishable among the examined primates. The plotted curve for each genus exhibits about the same range of motion. The human, chimpanzee and baboon are all shown to produce about four degrees of flexion-extension at this joint. Differences appear to be more related to starting position than to movement ranges. Inasmuch as these starting positions are relevant, the human values are intermediate between that of the ape and monkey.

Perhaps more interesting is the dichotomous grouping of genera that appears in the average motion tracking of the talonavicular joint (Fig. 3). These average motion plots indicate that the essential kinematic differences may be produced by the medial foot and not the lateral foot, which agrees with the conclusions of Thompson, et al (2014). Furthermore, medial foot kinematics fails to distinguish the human foot and instead reveals a hominine (Homo and Pan) versus cercopithecine (Papio and Macaca) dichotomy. The natural posture of the cercopithecine foot is such that the calcaneal tuberosity does not typically contact the locomotor substrate, which is unlike the characteristic hominine foot posture (Gebo, 1992). This means that cercopithecines may not be considered to be fully plantigrade. Because we did not focus on this aspect of foot posture, we are unable to comment upon how much the observed kinematic dichotomy is due solely to the plantigrade foot posture or due to some other aspect of phylogeny. It may be interesting to note that recent research based upon observations of barefoot running (Lieberman, et al. 2010) indicates that not all humans always adopt a fully plantigrade posture during all styles of locomotion. It remains unknown how much this type of postural observation may also apply to other hominines or may apply in reverse to cercopithecines. The degree to which foot posture influences primate foot joint kinematics remains an open question. Nonetheless, under the experimental conditions imposed by this study, there is an unambiguous separation between the hominines and the cercopithecines based on the movement response of the talonavicular joint.

Superimposition of the medial and lateral motion plots for humans and chimpanzees (Fig. 4) show that the two halves of the foot bend at similar magnitudes. It would appear that the patterns of midfoot flexibility do not reveal an “essential” human kinematic pattern that might be exclusively associated with bipedalism. There is no evidence within these data to support the notion that the lateral rigidity of the human foot is somehow special (cf. Lewis, 1980; Lamy, 1986; Berillion, 2003; Harcourt-Smith & Aiello, 2004; Jungers, et al. 2009). Midfoot flexibility during dorsiflexion appears to be present within the human foot to the same extent that it is present within the chimpanzee foot. Thus, it would appear that the midtarsal break of the chimpanzee is kinematically the same as midfoot longitudinal arch flattening of the human. In this context, the midtarsal break might be seen as a kinematic precursor to longitudinal arch compliance. Conversely, and as suggested by the recent observations of “ape-like” midfoot flexibility within humans (Crompton, et al. 2010; Bates, et al. 2013), the skeletal arrangement of the human foot cannot be seen to preclude the kinematic response associated with the midtarsal break. Similarly, the skeletal arrangement of the non-human primate foot need not be seen as always requiring a midtarsal break during locomotion. Instead, we infer from the similarity of the human and chimpanzee data that there is a uniform kinematic capability represented within the hominine foot with regard to midfoot flexibility. To be sure, humans and chimpanzees typically employ that capability differently. That is why these kinematic properties appear within these experimental data, but may be less obvious in data that describe naturalistic locomotor behaviors. Nonetheless, the data indicate the expression of a single basic hominine kinematic pattern. The implication of these interpretations is that the practice of a midtarsal break may not be easily identified within the morphological features of the foot skeleton.

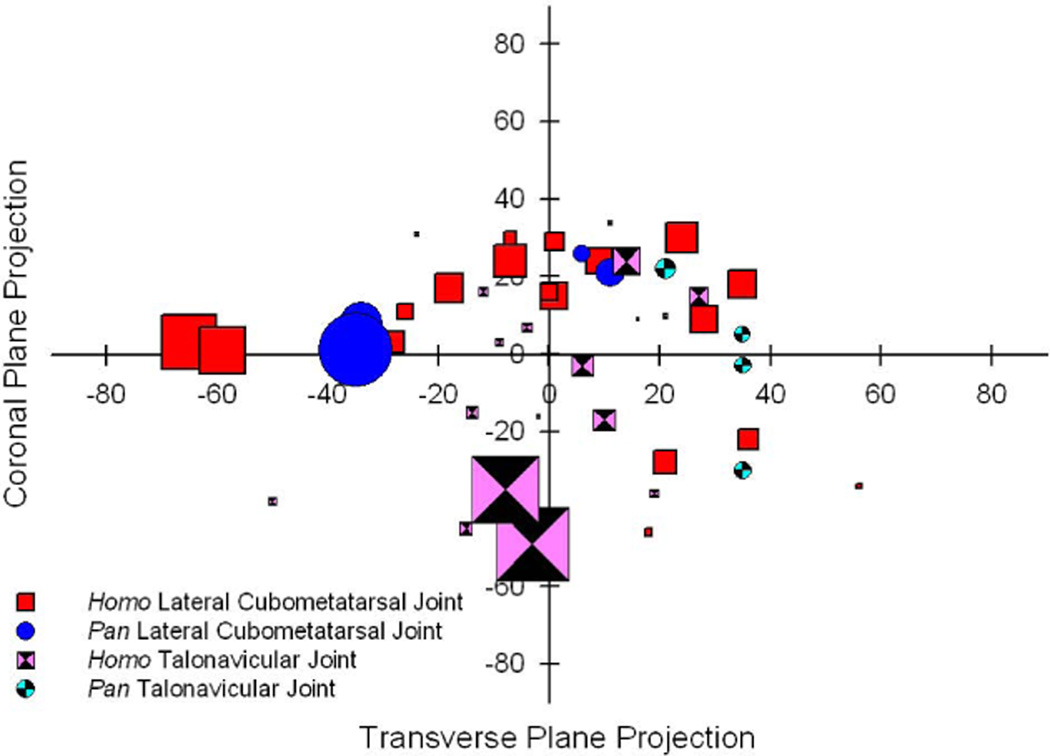

Simultaneous consideration of motion and rotational axis orientation (Fig 6) complicates the interpretation of hominine foot kinematics. An examination of the average orientations for the lateral cubometatarsal joint axes (Fig 5) shows that humans and chimpanzees are fairly close. Coupling that information with the motion (Fig 2 and Fig 6) shows that chimpanzees fall well within the human range of variation. Note that it is the humans and not the chimpanzees which display some individuals with exceptionally high joint mobility. Very little can be said at this time about the function of this joint in the monkey since the presented motion pattern (Fig 2) and axis orientation (Table 3) is based upon only one individual. Nonetheless, the reported value for that one baboon fits comfortably within the ranges described for both the human and the chimpanzee. Closer examination of the relevant axis orientation values reported for individual subjects (Tables 2 and 3 and Figure 6) shows that variation between individuals is much greater than the variation between species. It appears that few meaningful interpretations about the function of the lateral longitudinal foot arch, and the presumed bipedal affinities of fossil hominines, should be derived from analyses of the components of the calcaneocuboid or the cubometatarsal joints. These conclusions do not support assumptions that are associated with several, presumably functionally based, analyses of hominine fossils and human bipedal evolution (Bojsen-Møller 1979; Lewis, 1980; Susman, 1983; Kidd, 1999; Klenerman & Wood, 2006; Bennet, et al. 2009; Lovejoy, et al. 2009; Ward, et al 2011; Zipfel, et al 2011; Proctor, 2013).

Figure 6.

A comparison of the kinematics of the lateral cubometatarsal joint and talonavicular joint in both humans (Homo) and chimpanzees (Pan). The location of a symbol represents the orientation of the joint’s rotational axis as simultaneously projected onto the transverse and coronal anatomical planes; each axis is scaled from −90 to +90 degrees. The size of the symbol represents the range of motion observed to occur about the axis, so that the larger the symbol the greater the observed motion. The kinematics of the chimpanzee joints appear to fall well within the range of variation observed for the human joints.

For both humans and chimpanzees, the average orientation of the talonavicular joint’s rotational axis is unlike that of the lateral cubometatarsal joint (Figs 5 and 6). Clinical literature has shown this difference in humans (Elftman & Manter, 1935b; Manter, 1941; Elftman, 1960; Ouzounian & Shereff, 1989; Astion, et al. 1997; Sammarco & Hockenbury, 2001; Nowak, et al. 2010), although we infer that some of these researchers may have been examining dorsiflexion at the lateral cubometatarsal joint and not the calcaneocuboid joint as is commonly reported. The difference in the medial and lateral foot joint axes has been associated with a “locking” mechanism that converts the human foot into a rigid lever for effective propulsion at toe-off. Comparative biomechanics and evolutionary literature (Elftman & Manter, 1935a; Elftman, 1960; Sammarco & Hockenbury, 2001; Klenerman & Wood, 2006) have taken this locking mechanism to be an important element in the development of human bipedalism. This locking mechanism would become more effective as increasingly divergent orientations of the rotational axes reduce the likelihood for simultaneous flexion-extension of the medial and lateral foot. The observed axis orientations may be responsible for preventing the talonavicular and lateral cubometatarsal joints from displaying greater mobility during the driving action, even though each joint may be individually capable of greater mobility if it were to be evaluated in isolation. Kinematic evidence of this locking mechanism in action can be seen in the similar four degree range of motion reported for each joint. Because of the potential restrictive role of axis orientation, it is interesting to note that chimpanzee joints show less variability and a more uniform separation in the orientations of the talonavicular and lateral cubometarsal joint axes when projected onto the transverse plane. We would not go so far as to suggest that these joint orientations imply that the chimpanzee foot locking mechanism is more effective than that of the human. It is worth noting that the kinematic variations displayed for the chimpanzee joints (Fig. 6) fall well within the kinematic variation displayed for the human joints. It appears that this “essential” hallmark of bipedalism in the function of the human foot may not be a uniquely human characteristic.

We have twice advanced the interpretation that, with respect to the kinematics of midfoot flexibility, the human foot is not particularly unique. At least it is not unique when compared to the non-human primates we examined. Because of this conclusion, it becomes important to call attention to the limitations of kinematic data collection methods.

Many kinematic analyses involve a three-dimensional input, such as naturalistic walking, but confine the evaluation of motion to a two-dimensional plane. This restriction to data collection is sometimes necessitated by the vagaries of research design. For example, living non-human primates cannot be expected to follow uniform data collection protocols and so two-dimensional data collection may be the only method of data capture that is practicable. Nonetheless, there are important differences between a two-dimensional and a three-dimensional kinematic analysis. When a joint is evaluated in an orientation that is oblique to the two-dimensional output plane, motions that naturally occur about multiple rotational axes will be projected onto the two-dimensional output plane. This will cause a summation of the motions about the three separate rotational axes to be interpreted as if they were motions about a single rotational axis that is artificially imposed to emerge from the two-dimensional plane. For example, a recent report on chimpanzee foot kinematics (Thompson, et al 2014) employs a similar concept of evaluating motion based upon an experimentally controlled sagittal plane driving action, but limits assessment of motion to the two-dimensional cineradiographic plane. It is therefore unsurprising that their reported motion values are different from those reported here. From a two-dimensional presentation there is no way to determine how much of the observed motion results from the oblique orientation of the rotational axis. Similarly, there is no way to distinguish among the individual motion contributions of each of the three rotational axes. A three-dimensional data capture and analysis avoids these issues. The influences of posture orientation and multiple rotational axes can be addressed by identifying motion about a functionally derived axis whose orientation is defined relative to the anatomy of the specimen. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that while the reported motion values based upon two-dimension data capture methods (e.g., DeSilva 2010; Gatt, et al. 2011; DeSilva & Gill, 2013; Thompson, et al. 2014) differ from those reported here, the interpretation of the relative contributions to midfoot flexibility from the evaluated joints is essentially the same.

The best kinematic data come from studies where bone pins are inserted into living subjects (e.g., Lundgren, et al. 2008; Wolf, et al. 2008). In vivo bone pin studies provide the only data that describe unassailably coherent biologic movement. Yet, because ethical and practical constraints frequently limit in vivo sample sizes, these studies can fall short in their ability to appreciate biological variability. Furthermore, the sensitivity associated with surgically placed bone pins means that the utility of this method would be limited in studies of non-human primates. The alternative in vivo approach based upon the use of surface markers is well established. However, limitations due to skin surface artifact mean that this method is best used to evaluate larger limb segment kinematics (e.g., Gatt, et al. 2011) and is not suited for the evaluation of smaller, intrinsic, joints.

Several in vitro studies attempt to replicate in vivo conditions by evaluating fresh anatomical specimens, wherein most tissue remains intact. Simulation based in vitro approaches, as well as some approaches in silico (e.g., Crompton, et al. 2010; Crompton, et al. 2012), have the appeal of attempting to mimic the living condition. These investigations often employ a system that applies prescribed loads and tensions to the specimen, and sometimes to specific bones and muscle tendons. A well known procedure (Kitaoka, et al. 1997; Nester, et al. 2007) uses a computer assisted system to pull on muscle tendons in a way that replicates “average” muscle firing patterns obtained from electromyographic studies of human locomotion. This method has fascinating potential for experimental motion studies. Still, only muscles with tendons accessible within the leg can be “activated.” There is no way to incorporate the functions of the smaller intrinsic foot muscles, which therefore literally act as dead weight during the simulation. More importantly, employing average muscle activation patterns cannot be assumed to be replicating subject specific muscle activation patterns. Thus, even the best attempts at replicating natural movement patterns in vitro are still artificial.

The method used in our study embraced the necessity of artifice by limiting the driving motion to a simple controlled action that would be the same for each subject – similar in benefits and in shortcomings. Preparing a specimen by removing all non-ligamentous tissue avoids the possibility of muscular restrictions. This avoids the unwanted restrictions that might be present in cadaver specimens due to rigor mortis. However, it also excludes the wanted muscle restrictions due to the isometric and antagonistic muscular contractions that occur during any coordinated activity. Thus, we evaluated only the skeletal kinematic chain. As such, each joint is presumed to be hyper mobile and the resulting observations must be interpreted to represent potential movements rather than living kinematic patterns. By controlling the input motion to a single uniplanar plantarflexion-dorsiflexion driving action, we are able to describe the biomechanical linkages and passive movement potential that might occur during this action.

What we have reported and interpreted here are kinematic capabilities. Capabilities are different from utilizations. Similarly, our data are driven by an artificial activity – plantarflexion-dorsiflexion of the tibia over the foot. While this movement is certainly an important component of normal locomotion, normal locomotion is also associated with a number of other complex musculoskeletal interactions. Where our kinematic investigation differs from many others is that we have maintained experimental control over the driving action. By limiting our study to plantarflexion-dorsiflexion we begin to tease out how the individual components of locomotion interact and thereby contribute to an understanding of the complexity of intrinsic foot motion. Input driving motions with greater complexity, such as occurs during the bipedal gait cycle, would undoubtedly generate different kinematic patterns among the investigated joints. Human gait patterns are not natural to a chimpanzee or to any other non-human primate. It is not possible to create a driving motion that is both natural and equivalent to all investigated primates. However, the utilized plantarflexion-dorsiflexion cycle is a recognized component of all lower/hind-limb locomotor cycles and is therefore equally natural, or unnatural, to all subjects.

This study contributes to a greater understanding of primate intrinsic foot joint complexity. We conclude that the human foot is capable of producing the same levels of midfoot flexibility as seen in the chimpanzee, and that this flexibility occurs at the same joints. Thus, the capacity for the “midtarsal break” cannot be excluded from normal human foot function. Similarly, the mechanism that has been proposed for converting a compliant foot into a locked and rigid structure is equally identifiable in human and chimpanzee feet. We do not claim that these kinematic functions are always, or even usually, utilized within the locomotor patterns of different primates. It is the selection of actions among a suite of biomechanical capabilities that defines the locomotor repertoire. Modern humans exercise a different selection than do modern chimpanzees. For example, African ape locomotion typically encompasses a lateral to medial roll during stance phase (Gebo, 1992) that is much greater and occurs in a different sequence than what is seen during typical human walking. The difference between these loading patterns represents choices of locomotor style that may diminish (for the ape) or accentuate (for the human) the effect of the foot locking mechanism produced by the differing joint rotational axis orientations. Persons who choose to practice a more ape-like lateral-to-medial roll during stance phase may be responsible for the reports of “ape-like” midfoot flexibility within some humans (Crompton, et al. 2010; Bates, et al. 2013). This would reinforce the notion that the ape-human difference in midfoot flexibility is more one of habitual utilization choices and less one of differing kinematic capabilities. When a kinematic capability is identified within both genera it is reasonable to infer that this capability was present within the evolutionary lineages derived from their common ancestor. These similarities suggest that the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees may have possessed biomechanical linkages within the foot skeleton that yielded a uniform capacity for midfoot flexibility across the medial and lateral (talonavicular and lateral cubometatarsal) joints, which produced the capacity for a midtarsal break during the stance phase of gait. However, within this common ancestor the midtarsal joints also rotated about axes with opposing orientations. This means that the common ancestor may have also possessed a capacity for producing a rigid foot during locomotor push off. We suggest that these two capacities of the skeletal linkages might be identified as “biomechanical synapomorphies” of the hominine foot. Although we have presented only one small piece of the puzzle that is primate foot kinematics, we begin to agree with Crompton, et al (2010) that the bipedal human foot may not be kinematically unique. Instead, it may be better viewed as a unique combination of unremarkable kinematic capabilities that exist within the foot of nearly every primate.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Financial support provided by a University of Wisconsin-La Crosse Faculty Research Grant. Non-human specimens provided by the National Primate Research Center at the University of Washington, supported by NIH grant RR00166; The Southwest National Primate Research Center grant P51 RR013986 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health and that are currently supported by the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs through P51 OD011133; University of Louisiana at Lafayette New Iberia Research Center; and the Biological Resources Laboratory University of Illinois at Chicago. Our respect and gratitude is extended to the human individuals, and their families, who donated their bodies to the anatomical education and research programs that are associated with this project.

Contributor Information

Thomas M. Greiner, Dept. of Health Professions, University of Wisconsin- La Crosse, La Crosse, WI 54601 USA

Kevin A. Ball, Dept. of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Hartford, West Hartford, CT 06117 USA

LITERATURE CITED

- Astion DJ, Deland JT, Otis JC, Kenneally S. Motion of the hindfoot after simulated arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1997;97A:241–246. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199702000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball KA, Greiner TM. On the problems of describing joint axis alignment. J Biomech. 2008;417:1599–1603. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball KA, Greiner TM. A procedure for analysis and interpretation of joint movement: Functional Alignment. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Eng. 2012;15:487–500. doi: 10.1080/10255842.2010.545821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball KA, Pierrynowski MR. Classification of errors in locating a rigid body. J Biomech. 1996;29:1213–1217. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(96)00008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates KT, Collins D, Savage R, McClymont J, Webster E, Pataky TC, D’Août K, Sellers WI, Bennett MR, Crompton RH. The evolution of compliance in the human lateral mid-foot. Proc R Soc B. 2013;280 doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.1818. 20131818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MR, Harris JWK, Richmond BG, Braun DR, Mbua E, Kiura P, Olago D, Kibunjia M, Omuombo C, Behrensmeyer AK, Huddart D, Gonzalez S. Early hominin foot morphology based on 1.5-million-year-old footprints from Ileret, Kenya. Science. 2009;323:1197–1201. doi: 10.1126/science.1168132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berillon G. Assessing the longitudinal structure of the early hominin foot: a two-dimensional architecture analysis. Hum Evol. 2003;18:113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwood CB, Yuen TJ, Sanggeorzan BJ, Ledoux WR. The midtarsal joint locking mechanism. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26:1074–1080. doi: 10.1177/107110070502601213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bojsen-Møller F. Calcaneocuboid joint and stability of the longitudinal arch of the foot at high and low gear push off. J Anat. 1979;129:165–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caravaggi P, Pataky T, Günther M, Savage R, Crompton R. Dynamics of longitudinal arch support in relation to walking speed: contribution of the plantar aponeurosis. J Anat. 2010;217:254–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall MW, McPoil TG. Relative movement of the navicular bone during normal walking. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20:507–512. doi: 10.1177/107110079902000808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crompton RH, Pataky TC, Savage R, D'Août K, Bennett MR, Day MH, Bates K, Morse S, Sellers WI. Human-like external function of the foot, and fully upright gait, confirmed in the 3.66 million year old Laetoli hominin footprints by topographic statistics, experimental footprint-formation and computer simulation. J R Soc Interface. 2012;9:707–719. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2011.0258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crompton RH, Sellers WI, Thorpe SKS. Arboreality, terrestriality and bipedalism. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2010;365:3301–3314. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Août K, Aerts P. The evolutionary history of the human foot. In: D’Août K, Lescrenier K, Van Gheluwe B, De Clercq D, editors. Advances in plantar pressure measurements in clinical and scientific research. Maastricht: Shaker Publishing; 2008. pp. 44–68. [Google Scholar]

- D’Août K, Aerts P, De Clercq D, De Meester K, Van Elsacker L. Segment and joint angles of hind limb during bipedal and quadrupedal walking of the bonobo Pan paniscus . Am J Phys Anthropol. 2002;119:37–51. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSilva JM. Revisiting the ‘midtarsal break’. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2010;141:245–258. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSilva JM, Gill SV. Brief communication: A midtarsal midfoot break in the human foot. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2013;151:495–499. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elftman H. The transverse tarsal joint and its control. Clin Orthop. 1960;16:41–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elftman H, Manter J. Chimpanzee and human feet in bipedal walking. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1935a;20:69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Elftman H, Manter J. The evolution of the human foot with special reference to the joints. J Anat. 1935b;70:56–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdemir A, Hamel AJ, Fauth AR, Piazza SJ, Sharkey NA. Dynamic loading of the plantar aponeurosis in walking. J Bone Joint Surg. 2004;86A:546–552. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200403000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatt A, Chockalingam N, Chevalier TL. Sagittal plane kinematics of the foot during passive ankle dorsiflexion. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2011;35:425–431. doi: 10.1177/0309364611420476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebo DL. Plantigrady and foot adaptation in African apes: implications for hominid origins. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1992;89:29–58. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330890105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomberg DN. Functional differences of three ligaments of the transverse tarsal joint in hominoids. J Hum Evo. 1985;14:553–562. [Google Scholar]

- Greiner TM. Correlated joint rotations in the medial foot and the definition of plantarflexion-dorsiflexion. J Foot Ankle Res. 2012;5(Suppl. 1):O41. [Google Scholar]

- Greiner TM. Complications in cross-species comparisons of joint kinematics: An example from the primate foot. Am J Phys Anthropol Supplement. 2013;54:136–137. [Google Scholar]

- Greiner TM, Ball KA. Assessing talonavicular joint rotations in three dimensions. J Foot Ankle Res. 2008a;1(Suppl. 1):O50. [Google Scholar]

- Greiner TM, Ball KA. The Calcaneocuboid joint moves with three degrees of freedom. J Foot Ankle Res. 2008b;1(Suppl. 1):O39. [Google Scholar]

- Greiner TM, Ball KA. Statistical analysis of the three dimensional joint complex. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Eng. 2009;12:185–195. doi: 10.1080/10255840903091494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiner TM, Ball KA. Identifying the transverse tarsal joints of the foot. FASEB J. 2010;24 637.10. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks JH. The mechanics of the foot. I. The joints. J Anat. 1953;87:345–357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks JH. The mechanics of the foot. II. The plantar aponeurosis and the arch. J Anat. 1954;88:25–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harcourt-Smith WEH, Aiello LC. Fossils, feet and the evolution of human bipedal locomotion. J Anat. 2004;204:403–416. doi: 10.1111/j.0021-8782.2004.00296.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaung R, Cook P, Bylth P. A comparison of embalming fluids for use in surgical workshops. Clin Anat. 2011;24:166–161. doi: 10.1002/ca.21118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungers WL, Harcourt-Smith WEH, Wunderlich RE, Tocheri MW, Larson SG, Sutikna T, Due RA, Morwood MJ. The foot of Homo floresiensis . Nature. 2009;459:81–84. doi: 10.1038/nature07989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd R. Evolution of the rearfoot: A model of adaptation with evidence from the fossil record. J. Am Pediatr Med Assoc. 1999;82:2–17. doi: 10.7547/87507315-89-1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitaoka HB, Ahn T-K, Luo ZP, An K-N. Stability of the arch of the foot. Foot Ankle Int. 1997;18:644–648. doi: 10.1177/107110079701801008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klenerman L, Wood B. The human foot: A companion to clinical studies. London: Springer-Verlag; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lamy P. The settlement of the longitudinal plantar arch of some African plio-pleistocene hominids: a morphological study. J. Hum. Evo. 1986;15:31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis OJ. The joints of the evolving foot part II, the intrinsic joints. J. Anat. 1980;131:275–298. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman DE, Venkadesan M, Werbel WA, Daoud AI, D’Andrea S, Davis IS, Mang’Eni RO, Pitsiladis Y. Foot strike patterns and collision forces in habitually barefoot versus shod runners. Nature. 2010;463:531–535. doi: 10.1038/nature08723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy CO, Latimer B, Suwa G, Asfaw B, White TD. Combining prehension and propulsion: the foot of Ardipithecus ramidus . Science. 2009;326:72e1–72e8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren P, Nester C, Liu A, Arndt A, Jones R, Stacoff A, Wolf P, Lundberg A. Invasive in vivo measurement of rear-, mid- and forefoot motion during walking. Gait Posture. 2008;28:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manter JT. Movements of the subtalar and transverse tarsal joints. Anat Rec. 1941;80:397–410. [Google Scholar]

- Meldrum DJ. Midfoot flexibility, fossil footprints, and sasquatch steps: new perspectives on the evolution of bipedalism. J Sci Explor. 2004;18:65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Nester CJ, Liu AM, Ward E, Howard E, Cocheba J, Derrick T, Patterson P. In vitro study of foot kinematics using a dynamic walking cadaver model. J Biomech. 2007;40:1927–1937. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak MG, Carlson KJ, Patel BA. Apparent density of the primate calcaneo-cuboid joint and its association with locomotor mode, foot posture, and the ‘‘midtarsal break.’’. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2010;142:180–193. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouzounian TJ, Shereff MJ. In vitro determination of midfoot motion. Foot Ankle. 1989;10:140–146. doi: 10.1177/107110078901000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor DJ. Proximal metatarsal articular surface shape and the evolution of a rigid lateral foot in hominins. J Hum Evo. 2013;65:761–769. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammarco GJ, Hockenbury RT. Biomechanics of the foot and ankle. In: Nordon M, Frankel VH, editors. Basic biomechanics of the musculoskeletal system. 3rd edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams, Wilkins; 2001. pp. 222–255. [Google Scholar]

- Stern JT, Susman RL. The locomotor anatomy of Australopithecus afarensis . Am J Phys Anthropol. 1983;60:279–317. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330600302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susman RL. Evolution of the human foot: evidence from plio-pleistocene hominids. Foot Ankle. 1983;3:365–376. doi: 10.1177/107110078300300605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan C, Dunn S, Kent GN, Randall AG, Edmondston SJ, Singer KP. The effect of formalin-fixation on collagen and elastin crosslinks in human spinal discs and ligamentum flavum. J. Musculoskeletal Research. 2002;6:89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson NE, Holowka NB, O'Neill MC, Larson SG. Brief communication: Cineradiographic analysis of the chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) talonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2014;154:604–608. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vereecke EE, Aerts P. The mechanics of the gibbon foot and its potential for elastic energy storage during bipedalism. J Exp Biol. 2008;211:3661–3670. doi: 10.1242/jeb.018754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vereecke EE, D’Août K, De Clercq D, Van Elsacker L, Aerts P. Dynamic plantar pressure distribution during terrestrial locomotion in bonobos Pan paniscus . Am J Phys Anthropol. 2003;120:373–383. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward CV, Kimbel WH, Johanson DC. Complete fourth metatarsal and arches in the foot of Australopithecus afarensis . Science. 2011;331:750–753. doi: 10.1126/science.1201463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf P, Stacoff A, Liu A, Nester C, Arndt A, Lundberg A, Stuessi E. Functional units of the human foot. Gait Posture. 2008;28:434–441. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel B, DeSilva JM, Kidd RS, Carlson KJ, Churchill SE, Berger LR. The foot and ankle of Australopithecus sediba . Science. 2011;333:1417–1420. doi: 10.1126/science.1202703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]