Abstract

Several members of the zinc-dependent matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) family catalyze collagen degradation. The structures of MMPs, in solution and solid state and in the presence and absence of triple-helical collagen models, have been assessed by NMR spectroscopy, small-angle X-ray scattering, and X-ray crystallography. Structures observed in solution exhibit flexibility between the MMP catalytic (CAT) and hemopexin-like (HPX) domains, while solid-state structures are relatively compact. Evaluation of the maximum occurrence (MO) of MMP-1 conformations in solution found that, for all the high MO conformations, the CAT and HPX domains are not in tight contact, and the residues of the HPX domain reported to be responsible for the binding to the collagen triple-helix are solvent exposed. A mechanism for collagenolysis has been developed based on analysis of MMP solution structures. Information obtained from solid-state structures has proven valuable for analyzing specific contacts between MMPs and the collagen triple-helix.

1. MMPs AND COLLAGEN HYDROLYSIS

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a family of zinc-dependent proteolytic enzymes. Several members of the MMP family are capable of catalyzing the hydrolysis of triple-helical, interstitial (types I–III) collagen (Fields, 2013). Prior to collagen catabolism, MMPs bind to numerous regions within the collagen triple-helix (Sun, Smith, Hasty, & Yokota, 2000). MMPs then progressively move on collagen fibrils (Saffarian, Collier, Marmer, Elson, & Goldberg, 2004). The mechanism by which MMPs catabolize collagen has been postulated for decades. Recent structural studies of MMPs, in both solution and the solid state, have shed significant light on the enzyme conformations that may participate in collagenolysis. In turn, these structural studies have been utilized to develop models for the stepwise degradation of collagen. Some controversy has arisen due to contradictions between the stepwise models. The contradictions may well be based on the different conditions by which MMP structures were obtained.

2. STRUCTURES OF FULL-LENGTH, COLLAGENOLYTIC MMPs IN SOLUTION AND IN THE SOLID STATE

Full-length MMP-1 structures have been obtained by X-ray crystallographic and NMR spectroscopic analyses. Initially, the X-ray crystallographic structure of full-length, active porcine MMP-1 complexed with N-[3-(N′-hydroxycarboxamido)-2-(2-methylpropyl)-propananoyl]-O-methyl-L-tyrosine-N-methylamide (CIC) was solved (Li et al., 1995). Subsequently, the structure of full-length, activated human MMP-1 Glu219Ala mutant was obtained (pdb: 2CLT) (Iyer, Visse, Nagase, & Acharya, 2006). The activated human MMP-1 structure was highly similar to the structure of porcine full-length MMP-1, with an average root mean square deviation of ~1.4 Å (Iyer et al., 2006).

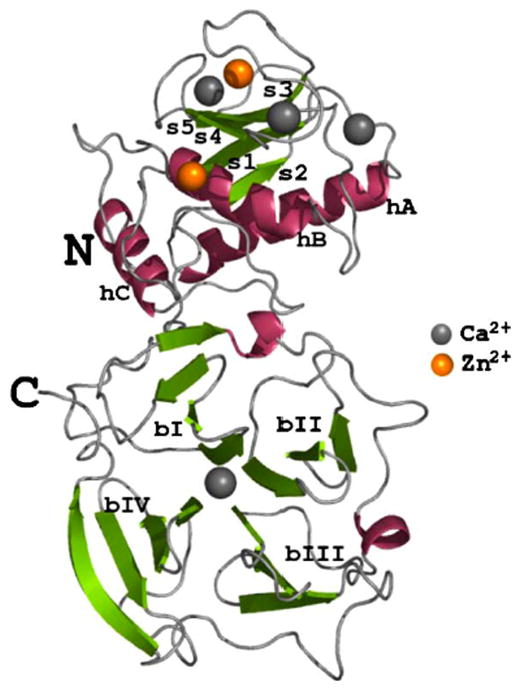

The full-length active MMP-1 structure included the N-terminal catalytic (CAT) domain, the linker region, and the C-terminal hemopexin-like (HPX) domain (Fig. 1) (Iyer et al., 2006; Li et al., 1995). The CAT domain possesses five β-strands and three α-helices (Fig. 1). The active site within the CAT domain is too small (~5 Å) to accommodate the collagen triple-helix (~15 Å) (Li et al., 1995). The HPX domain is a four-bladed β-propeller, where the blades are notated as bI, bII, bIII, and bIV (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Ribbon representation of the three-dimensional structure of activated, full-length human MMP-1 Glu219Ala mutant. Helices have been colored pink (dark gray in the print version) and the strands shown in green (dark gray in the print version). There are four calcium ions and two zinc ions found in the structure that have been colored gray and orange (light gray in the print version), respectively. The secondary structural elements have been annotated: helices (hA–hC), strands (s1–s5) of the CAT domain, and blades (bI–bIV) of the HPX domain. Reproduced from Iyer et al. (2006) by the permission of Elsevier.

X-ray crystallographic structures have also been solved for full-length proMMP-1 and MMP-13. Comparison of proMMP-1 and activated MMP-1 indicated that activated human MMP-1 had significant movement in the HPX domain compared with proMMP-1. The magnitude of this movement was exemplified by Phe308, where the displacement was 16 Å (Iyer et al., 2006). The movement of the HPX domain toward the CAT domain widened the cleft between the domains on the active site face of the enzyme (Iyer et al., 2006). It was proposed that Arg300 functioned as a pivot for this displacement (Iyer et al., 2006).

The structure of activated full-length human MMP-13 Glu223Ala mutant showed some distinct differences from activated human MMP-1 (Stura, Visse, Cuniasse, Dive, & Nagase, 2013). Most notably, the HPX domain was rotated by ~30° and translated compared with the MMP-1 HPX domain. The displacement was due to changes in the interface between the CAT and HPX domains. The residues Pro236 and Leu322 in MMP-13, replacing Ile and Phe, respectively, in MMP-1, allowed the MMP-13 CAT and HPX domains to move closer together than in MMP-1. Analysis of peptide interactions within the MMP-13 CAT domain implicated the presence of substrate-dependent secondary binding sites (exosites) (Stura et al., 2013).

The radii of gyration (Rg) of the activated human MMP-1 crystallographic structure (2CLT) was 25.7 Å, whereas experimentally determined values from small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) data yielded Rg = 28.5–29.0 Å (Arnold et al., 2011; Bertini et al., 2009). The X-ray structures were thus more compact than the average solution conformation. In similar fashion, SAXS and single-molecule atomic force microscopy (AFM) analysis of proMMP-9 (Rosenblum et al., 2007) indicated an elongated ellipsoid structure, with Rg = 50±2.7 Å. The domains were separated by ~30 Å.

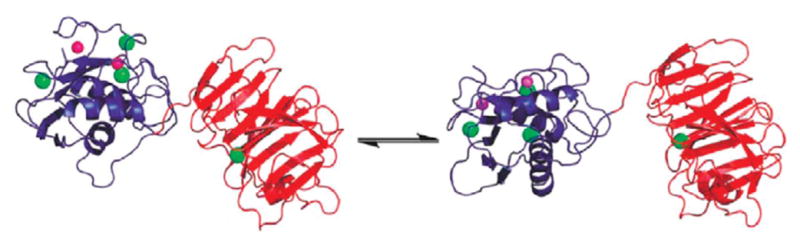

Full-length active human MMP-1 Glu219Ala mutant was observed by NMR spectroscopy and SAXS to experience a sizable interdomain flexibility and an open-closed equilibrium (Fig. 2) (Arnold et al., 2011; Bertini et al., 2009). Paramagnetic NMR spectroscopic and SAXS data were subsequently used to calculate the maximum occurrence (MO) of conformations of MMP-1 in solution (Cerofolini et al., 2013).

Figure 2.

Closed (left) and open/extended (right) forms of full-length MMP-1 in equilibrium. Reproduced from Bertini et al. (2012) by the permission of the American Chemical Society.

Many of the MMP-1 conformations with the highest MO value were found to have interdomain orientations and positions that could be grouped into a cluster. The structures with the highest MO (>35%) had Rg of 29±1.3 Å, further demonstrating that the X-ray structures were more compact than the average solution conformation. Furthermore, the relative orientations of the HPX and CAT domains in the structures with the highest MO were different from those in the X-ray crystallographic structures.

The MO values obtained for the X-ray structures 1SU3 (proMMP-1) and 2CLT (activated MMP-1) were 20% and 19%, respectively. Thus, the compact arrangements of the MMP-1 CAT and HPX domains observed in the X-ray crystallographic structures are not fully representative of the conformations sampled by the protein in solution.

3. STRUCTURAL EVALUATION OF MMP INTERACTIONS WITH COLLAGEN

Unique regulatory sites have been predicted for all members of the MMP family (Udi et al., 2013). A prior study on hydrolysis of collagen by MMP-1, MMP-1 mutants, and general proteases led to the proposal that the collagen triple-helix binds to exosites in the MMP and is then locally unwound/destabilized to allow entry of a single strand into the active site (Chung et al., 2004). Binding sites for the triple-helix within the MMP-1 HPX domain have been identified in solution using hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) (Lauer-Fields et al., 2009) and NMR spectroscopy (Arnold et al., 2011; Bertini et al., 2012) and in the solid state by X-ray crystallography (Manka et al., 2012). In all cases, triple-helical peptide (THP) models were complexed with MMP-1.

Initially, using HDX-MS and mutational analysis, in MMP-1, Ile290 and Arg291 in the HPX domain A–B loop of blade I were identified as key residues in collagenolysis (Lauer-Fields et al., 2009). Subsequently, NMR spectroscopic studies implicated HPX domain Phe301, Val319, and Asp338 in collagen binding (Fig. 3) (Arnold et al., 2011). Based on the X-ray crystallographic structure of an MMP-1/THP complex (pdb: 4AUO), Phe320 was found to be an important contributor, along with Ile290 and Arg291, to the S10′-binding pocket (Fig. 4) (Manka et al., 2012). The S10′-binding pocket bound the P10′ subsite of the THP, which possessed a Leu residue important for the interaction of triple-helices with MMP-1 (Arnold et al., 2011; Manka et al., 2012; Robichaud, Steffensen, & Fields, 2011). In MMP-13, the S10′ pocket is shifted, with Arg297 at one edge of the pocket moved 7.3 Å relative to MMP-1 (Stura et al., 2013).

Figure 3.

THP recognition surface on the MMP-1 HPX domain as identified by NMR spectroscopy. The HPX domain residues are colored according to the line broadening data from Arnold et al. (2011). The colors range from blue (dark gray in the print version) to cyan (white in the print version), green (light gray in the print version), yellow (white in the print version), and red (light gray in the print version) over the relative intensity range of 40–20%. In panel (B), the HPX domain has been rotated through 180° about the y-axis. Reproduced from Arnold et al. (2011) by the permission of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

Figure 4.

X-ray crystallographic structure of the MMP-1(E219A)/THP complex. Stereo-view of the interactions of the THP chains with the HPX domain. Selected residues making enzyme–substrate contacts are labeled with respective colors and shown in stick representation (N, dark blue, gray in the print version; O, red, dark gray in the print version). The residue numbering does not include the 19-amino acid signal sequence. Reproduced from Manka et al. (2012) by the permission of the National Academy of Sciences, USA.

MMP-1 Phe301 was identified as a binding site by NMR spectroscopy (Arnold et al., 2011) but was deemed as buried in the CAT domain/HPX domain interface by X-ray crystallography (Manka et al., 2012). However, in the crystal structure of the MMP-1/THP complex, the THP bound to a closed form of MMP-1 (more closed than 2CLT), and the preferred collagen cleavage site was not correctly positioned for hydrolysis (Manka et al., 2012). This leaves some question as to the physiological relevance of the crystal structure of the MMP-1/THP complex (see later). Phe301 probably interacts with the triple-helix initially, but then is utilized for domain interaction during collagenolysis (Arnold et al., 2011). Other residues within the HPX domain may also participate in collagen binding (Fig. 4) (Arnold et al., 2011; Lauer-Fields et al., 2009; Manka et al., 2012). In general, the interactions between the triple-helix and the HPX domain are a combination of polar and apolar contacts and are mediated mainly through the 2T (middle) strand of the THP (Manka et al., 2012).

X-ray crystallographic studies of MMP-12 and MMP-8 identified contacts from a single-stranded collagen-like peptide after hydrolysis (Bertini et al., 2006). The peptide fragments Pro-Gln-Gly and Ile-Ala-Gly, representing the cleavage site in the α1(I) collagen chain by collagenolytic MMPs (Fields, 2013), were held in place in the active site (Fig. 5). The N-terminal Pro-Gln-Gly fragment had only a few stabilizing interactions. The carboxylate termini of the Gly residue bound to the active site zinc. A water molecule was also semicoordinated to the zinc and hydrogen bonded to the Glu219 residue that functioned in catalytic activity. As expected, the side chain of the Ile residue from the C-terminal Ile-Ala-Gly fragment entered the S1′ subsite of the enzyme. The peptide was stabilized by four hydrogen bonds with the backbone of the enzyme (carbonyl oxygen atom of Ile and the nitrogen atom of Leu181, nitrogen atom of Ala and the carbonyl oxygen atom of Pro238, carbonyl oxygen atom of Ala and the nitrogen atom of Tyr240, and the nitrogen atom of Gly and the carbonyl oxygen atom of Gly179). The N-terminal nitrogen atom of the Ile-Ala-Gly fragment was hydrogen bonded to the zinc-coordinated water molecule and one oxygen atom of Glu219. The Pro-Gln-Gly fragment left the active site cavity first. The Ile-Ala-Gly fragment underwent a rearrangement in the active site prior to release (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

(A) Two-peptide intermediate observed upon soaking active uninhibited MMP-12 crystals with the collagen fragment Pro-Gln-Gly-Ile-Ala-Gly. (B) Ile-Ala-Gly adduct of MMP-12. Reproduced from Bertini et al. (2006) by the permission of Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co.

4. MECHANISM OF COLLAGENOLYSIS

The initial interaction of MMP-1 with collagen is controversial and depends upon which structure is favored by MMP-1 in solution prior to binding the substrate (Bertini et al., 2012; Manka et al., 2012). The highest MO conformations sampled by MMP-1 when free in solution appeared to be much more poised for interaction with collagen than the compact X-ray crystallographic structures (Cerofolini et al., 2013). In the conformations belonging to this cluster (i) the collagen-binding residues of the HPX domain were solvent exposed and (ii) the CAT domain was already correctly positioned for its subsequent interaction with the collagen (Fig. 6). A structural rearrangement involving a ~50° rotation around a single axis of the CAT domain with respect to the HPX domain was sufficient to position the CAT domain right in front of the preferred cleavage site in triple-helical collagen. The transition seemed to be feasible at physiological temperature as the difference in free energy between these steps in the pathway was favorable (−0.133 kcal/mol).

Figure 6.

MMP-1 solution structure with the highest MO, where the structure in the right column was rotated 180° about the vertical axis with respect to the left column. Yellow (white in the print version) is the surface representation of MMP-1, blue (black in the print version) is the MMP consensus sequence HEXXHXXGXXH, and orange (light gray in the print version) is the MMP-1 catalytic Zn2+. The blue (dark gray in the print version) and red (gray in the print version) arrows indicate the directions of the helices hA and hC, respectively. Reproduced from Cerofolini et al. (2013) by the permission of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

The interaction of MMP-1 with a THP has been investigated utilizing NMR spectroscopy, leading to a plausible multistep mechanism for collagenolysis (Bertini et al., 2012). In this mechanism, the initial binding of the HPX domain to the collagen triple-helix through specific residues in blades I and II of the HPX domain is followed by the interaction of the CAT domain with the triple-helix in front of the cleavage site, and by a subsequent back-rotation of the CAT and HPX domains toward the closed conformation observed by X-ray crystallography that drives the unwinding/perturbation of the triple-helix and causes the displacement of one peptide chain into the active site (Fig. 7). The MMP-1/THP complex in which one strand of the triple-helix is displaced from the other two (Fig. 7B) was strongly supported by changes in intensity of the interhelical NOEs upon THP binding (Bertini et al., 2012). Hydrolysis of the first strand is presumably followed by rapid hydrolysis of the other two strands.

Figure 7.

The initial steps of collagenolysis. (A) The extended full-length MMP-1 binds THP chains 1T and 2T (the leading and middle strands, respectively) at Val23-Leu26 with the HPX domain and the residues around the cleavage site with the CAT domain. The THP is still in a compact conformation. (B) Closed full-length MMP-1 interacting with the released 1T chain (in magenta, dark gray in the print version). (C) After hydrolysis, both peptide fragments (C- and N-terminal) are initially bound to the active site. (D) The C-terminal region of the N-terminal peptide fragment is released. Reproduced from Bertini et al. (2012) by the permission of the American Chemical Society.

The binding of the MMP-1 CAT domain to the THP in front of the Gly-Ile sequence of chain 1T to be cleaved (Fig. 7A) is enthalpically favored and entropically disfavored. The isolated CAT domain has negligible affinity for the THP (Bertini et al., 2012), gaining the ability to bind once held in place by the HPX domain in MMP-1. The proposed back-rotation of MMP-1 toward the X-ray closed structure and the associated liberation of chain 1T from the compact THP structure (Fig. 7B) imply a balance of enthalpic gains (the closing of MMP-1 and the establishment of productive contacts between chain 1T and the active site of MMP-1) and losses (the breaking of the H bonds between chain 1T and the other two THP chains). The cleavage step (Fig. 7C) is energetically favorable (Welgus, Jeffrey, & Eisen, 1981).

The action of MMP-9 on triple-helical collagen fragments, as observed by AFM (Rosenblum et al., 2010), reflects similar behavior to that proposed for MMP-1 hydrolysis of collagen. Analysis of MMP-9 lobe-to-lobe distance showed that upon binding of collagen the enzyme goes from an elongated conformation in solution (lobe-to-lobe distance of 74±10 Å) to a more globular conformation upon binding (lobe-to-lobe distance of 60±20 Å). The conformational change was associated with denaturation of the triple-helix.

Models for collagenolysis have also been proposed based on X-ray crystallographic structures (Manka et al., 2012; Stura et al., 2013). In these models, significant movement of the triple-helix (3–6 Å), rotation/sliding of the triple-helix, and/or significant movement of a single strand from the triple-helix (~4 Å) is needed to accommodate a chain in the active site. It is not clear if these models are energetically favorable.

5. HETEROGENEITY IN MMP STRUCTURES

X-ray crystallographic and NMR spectroscopic structures of MMP-12 CAT bound to several inhibitors have been compared (Bertini et al., 2005). The structures were nonidentical, with many loops having dynamic behavior on a variety of timescales. Even with the same inhibitor bound to the S1′ subsite, the 245–248 region showed conformational heterogeneity. In general, different structures in the solid state (X-ray crystal) corresponded to mobility in solution (NMR). Analysis of other MMPs showed similar disorder in loop regions. The authors ultimately stated, “Flexibility/conformational heterogeneity in crucial parts of the CAT domain is a rule rather than an exception in MMPs, and its extent may be underestimated by inspection of one x-ray structure” (Bertini et al., 2005).

While X-ray crystallographic analysis of an MMP-1/THP complex has revealed binding of the THP to a closed form of MMP-1, it has been noted that the preferred collagen cleavage site was not correctly positioned for hydrolysis (Manka et al., 2012). The flexibility of MMP-1 domains, and particularly the highly favored extended conformation, has a critical role in enzyme function. The closed structures observed by X-ray crystallography appear to be most relevant for collagenolysis once the collagen has bound and the triple-helix is destabilized.

Acknowledgments

MMP studies in the Fields Laboratory have been supported by the National Institutes of Health (CA98799, AR063795, and NHLBI contract 268201000036C-0-0-1).

References

- Arnold LH, Butt L, Prior SH, Read C, Fields GB, Pickford AR. The interface between catalytic and hemopexin domains in matrix metalloproteinase 1 conceals a collagen binding exosite. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286:45073–45082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.285213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini I, Calderone V, Cosenza M, Fragai M, Lee YM, Luchinat C, et al. Conformational variability of matrix metalloproteinases: Beyond a single 3D structure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:5334–5339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407106102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini I, Calderone V, Fragai M, Luchinat C, Maletta M, Yeo KJ. Snapshots of the reaction mechanism of matrix metalloproteinases. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 2006;45:7952–7955. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini I, Fragai M, Luchinat C, Melikian M, Mylonas E, Sarti N, et al. Inter-domain flexibility in full-length matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284:12821–12828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809627200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini I, Fragai F, Luchinat C, Melikian M, Toccafondi M, Lauer JL, et al. Structural basis for matrix metalloproteinase 1 catalyzed collagenolysis. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2012;134:2100–2110. doi: 10.1021/ja208338j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerofolini L, Fields GB, Fragai M, Geraldes CFGC, Luchinat C, Parigi G, et al. Examination of matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) in solution: A preference for the pre-collagenolysis state. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288:30659–30671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.477240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung L, Dinakarpandian D, Yoshida N, Lauer-Fields JL, Fields GB, Visse R, et al. Collagenase unwinds triple helical collagen prior to peptide bond hydrolysis. EMBO Journal. 2004;23:3020–3030. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields GB. Interstitial collagen catabolism. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288:8785–8793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R113.451211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer S, Visse R, Nagase H, Acharya KR. Crystal structure of an active form of human MMP-1. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2006;362:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer-Fields JL, Chalmers MJ, Busby SA, Minond D, Griffin PR, Fields GB. Identification of specific hemopexin-like domain residues that facilitate matrix metalloproteinase collagenolytic activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284:24017–24024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.016873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Brick P, O’Hare MC, Skarzynski T, Lloyd LF, Curry VA, et al. Structure of full-length porcine synovial collagenase reveals a C-terminal domain containing a calcium-linked, four bladed b-propeller. Structure. 1995;15:541–549. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manka SW, Carafoli F, Visse R, Bihan D, Raynal N, Farndale RW, et al. Structural insights into triple-helical collagen cleavage by matrix metalloproteinase 1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:12461–12466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204991109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robichaud TK, Steffensen B, Fields GB. Exosite interactions impact matrix metalloproteinase collagen specificities. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286:37535–37542. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.273391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum G, Van den Steen PE, Cohen SR, Bitler A, Brand DD, Opdenakker G, et al. Direct visualization of protease action on collagen triple helical structure. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum G, Van den Steen PE, Cohen SR, Grossmann JG, Frenkel J, Sertchook R, et al. Insights into the structure and domain flexibility of full-length pro-matrix metalloproteinase-9/gelatinase B. Structure. 2007;15:1227–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffarian S, Collier IE, Marmer BL, Elson EL, Goldberg G. Interstitial collagenase is a Brownian rachet driven by proteolysis of collagen. Science. 2004;306:108–111. doi: 10.1126/science.1099179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stura EA, Visse R, Cuniasse P, Dive V, Nagase H. Crystal structure of full-length human collagenase 3 (MMP-13) with peptides in the active site defines exosites in the catalytic domain. FASEB Journal. 2013;27:4395–4405. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-233601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun HB, Smith GN, Jr, Hasty KA, Yokota H. Atomic force microscopy-based detection of binding and cleavage site of matrix metalloproteinase on individual type II collagen helices. Analytical Biochemistry. 2000;283:153–158. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udi Y, Fragai M, Grossman M, Mitternacht S, Arad-Yellin R, Calderone V, et al. Unraveling hidden regulatory sites in structurally homologous metalloproteases. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2013;425:2330–2346. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welgus HG, Jeffrey JJ, Eisen AZ. Human skin fibroblast collagenase: Assessment of activation energy and deuterium isotope effect with collagenous substrates. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1981;256:9516–9521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]