Abstract

Birth defects are a major cause of infant morbidity and mortality and contribute substantially to long-term disability. One out of every 33 babies is born with some type of birth defect. Despite decades of research on environmental, behavioral and genetic risk factors, the vast majority of birth defects still occur without known cause. It is possible that birth defects are largely stochastic (and unavoidable) events, at which efforts to investigate their causes would be futile and unjustified. In this commentary we argue for the continued research into risk/preventive factors of human birth defects, and outline why epidemiological studies are suitable for such endeavors. First we discuss what factors to target (genetic or environmental) and how to define the pertinent research questions. Then we present a short review of both epidemiological contributions in the past and approaches to advance the field in the future. After considering also their limitations, we conclude that modern epidemiologic approaches are invaluable to advance our understanding of risk factors for human birth defects, and that interdisciplinary collaborations will also be essential to further our knowledge.

Keywords: Congenital malformations, Birth defects, Risk factors, Epidemiology, Observational studies

Introduction to the scope of the commentary

This Era of austerity has forced funding agencies to constantly consider where to spend the scarce resources, and the resulting harsh trade-offs require prioritizing certain fields of study over others. Investigators have to anticipate and follow the funders’ directions; or take the risk and continue doing what they think is important, or simply know how to do. In that sense, there is competition both between and within fields of research. Shall all investigators go after popular topics such as obesity, or are orphan disorders such as many specific birth defects also relevant? Within birth defects research, shall we focus on genome analyses or on non-genetic causes; on animal models or on human studies? Or, perhaps more appropriate, shall we discuss what the most pressing questions are first, and which approaches can provide valid answers to these questions second? Inspired by a workshop on “Developing an Interdisciplinary Research Agenda for Genetics of Birth Defects” held at the US National Institutes of Health in 2014, we share some of our thoughts below.

1. First, is there anything to study or are most birth defects stochastic events?

To discuss whether epidemiologic methods are appropriate to study birth defects, we first have to decide whether we want to spend the limited research funding available to investigate birth defects at all. Let’s briefly review the burden and origins of birth defects: One out of every 33 babies is born with some type of birth defect.1 Deaths due to birth defects account for more than 21% of all infant deaths, making them the leading cause of infant mortality. Birth defects are also associated with serious and often life-long disabilities; they are a leading cause of years of potential life lost, and account for much of the disability in children in the U.S. and most developed countries. Worldwide, congenital anomalies are the 10th leading cause of loss of disability-adjusted life years, accounting for 2.9% of all years of life lived with disabilities.2,3 To achieve any reduction of this substantial infant mortality and childhood disability we need to understand why and how birth defects occur. But, can we?

Some identified causes of congenital malformations include chromosomal defects, single gene defects, and a few environmental agents. However, despite decades of research on environmental, behavioral and genetic risk factors, the vast majority (estimated at two-thirds) of birth defects still occur without known cause.4 Embryological processes are incredibly complex and inevitably subject to imperfections. In fact, as fundamental as biological variability is, so are the intrinsic errors of the processes. If birth defects are largely the result of stochastic, unavoidable events, then efforts to investigate their causes will be futile and unjustified. However, the existence of known clearly teratogenic agents suggests that others may remain unidentified. Moreover, deviant patterns of occurrence - across time, or between/within populations - also points toward non-stochastic influences. If research to date has allowed us to explain a third of human birth defects, advances in science (technology, methods, data) should be able to explain more of such probabilistic events, particularly when the causes are either commonly occurring, or rare but with high penetrance. Unless we believe that the majority of defects are a result of nature playing dice, identifying and understanding risk/preventive factors should have great implications for prevention and/or management of high-risk pregnancies. Conclusion: With only a small fraction of defects possible to predict or prevent with current knowledge, and all of the remainder unlikely to be just stochastic, it seems imperative to promote further research to identify risk/preventive factors for human birth defects.

2. Shall we focus on genetic or non-genetic causes?

It is widely accepted that deterministic causes of birth defects are genetic, environmental or, most likely, a combination of the two (i.e. multifactorial).5 However, despite this prevailing idea, there is insufficient evidence for us to estimate the specific contribution of genes, environment, or their interaction. Although it is widely accepted that some structural defects recur in families,6–13 very few large population-based studies have attempted to use information on familial clustering to quantify the genetic versus environmental influence for the liability of malformations. To inform future directions for both funders and researchers, efforts to quantify the relative contributions of genetic and/or environmental factors to birth defect etiology should be of top priority.

Since little can be done (for now) to modify genetic factors, prevention depends upon the detection of environmentally determined, modifiable teratogens. However, the genetic background may also be relevant for prevention since it may interact with other factors, which can themselves be modified. For example, among the few teratogens that have been identified are traditional anticonvulsants,14,15 yet far from all fetuses exposed to anticonvulsants will develop malformations. A case report of anticonvulsant-exposed dizygotic twins has showed that they can be discordant in physical features,16 and recent observations in pregnancy registers in the UK17 and Australia18 also suggest that the risk of anticonvulsant embryopathy may depend on genetic susceptibility to the teratogenic effect of these drugs. Conclusion: Without a formal quantification of the relative contribution of genetic and environmental causes, or their interaction, any prioritization will be a subjective preference of the decision maker. Epidemiological studies allow identification of both genetic and environmental risks on the population level; and some may allow the evaluation of gene-environment interactions as well. Population-based family designs can also be used to answer questions about genetic vs. environmental contributions to the (population) variation in birth defects, providing vital information for future research directions.

3. What are the pertinent question from a biologic, clinical or public health perspective?

If we agree it is important to investigate birth defects, the next step will be to identify what the pertinent questions are. From a public health perspective, the most important aim should be to (1) identify modifiable causes of birth defects, which will allow intervention and prevention of cases (e.g. by avoiding environmental exposures - teratogens). Additionally, it should be of great clinical value to 2) identify predictors of birth defects - incl. potential genetic influence – which can help inform family planning (e.g. from quantification of absolute risk in specific human populations) and reduce morbidity through targeted screening and early intervention. Conclusion: The most pressing question may be how to prevent, or at least predict, birth defects.

4. How can we answer these questions?

Given we agree on the pertinent questions, what would be the most suitable approaches to study them? Toxicological or in vitro studies provide limited information since we rarely know the specific teratogenic mechanisms.19 A classic example is Thalidomide, for which these mechanisms have remained unknown for decades. Animal models have provided vital insights to our understanding of common aspects of embryogenesis, and allow manipulations that would never be feasible in human studies. However, sometimes results are not directly translated into human risk because of considerable variations in teratogenic effects between mammalian species.20,21 In humans, clinical trials are often unfeasible because most risk factors are non-randomizable for logistic (e.g. genes) or ethical (e.g. smoking) reasons. Information from randomized experiments in humans would only be available either as a secondary safety outcome or in the few instances where they test preventive agents (e.g. folic acid supplementation).22 However, the former usually exclude women who might become pregnant, particularly if there is any suspicion of adverse effects from animal studies. Therefore, we are mostly left with observational studies, briefly summarized in the following sections.

5. What epidemiological designs are available and/or best?

General support for epidemiological approaches can be obtained from reviewing the historical evidence. For major teratogens such as thalidomide, which increases the risk of specific malformations more than 100-fold, clinical observations were able to identify clusters of exposed and affected mother-offspring pairs.23–25 Even then, over 10,000 children had been affected by the time the drug was retracted from the market. Unlike thalidomide, most known teratogens will have more modest risk, making their identification more challenging.26 To avoid another thalidomide tragedy we now have proactive surveillance systems for pharmaceuticals, described below, which have helped to successfully identify also more modest teratogens (e.g., traditional anticonvulsants).27 Some epidemiological studies have been specifically designed to study birth defects, such as the large cohort study of over 50,000 pregnancies in the U.S. Collaborative Perinatal Project.28 Despite the large sample size, this study was nevertheless unable to evaluate most specific drugs, given the relatively small number of women exposed and the relatively rare outcomes under consideration.29 Nowadays, cohort studies commonly focus on pregnancies specifically exposed to the factor (drug) of interest: i.e. pregnancy registries.30 Yet, it still takes time to find and enroll enough numbers of exposed women soon after conception; and the registries often have limited sample sizes to look at specific malformations. For specific malformations we favor case-control studies of birth defects, which would be more efficient if the exposure is not too infrequent.31 Observations from these epidemiological designs have contributed to establish what is arguably the flagship for birth defects prevention, namely periconceptional folic acid supplementation to prevent neural tube defects (NTDs).32,33 One lesson learnt from these folic acid studies is that well-conducted observational studies can be as valid as randomized clinical trials to identify preventive factors for birth defects.34 Finally, in the last decade, epidemiologists are increasingly using information from health care databases, i.e., administrative claims files, electronic medical records, or well-established population registers of health and demographic characteristics (e.g. from Scandinavian countries).35,36 These sources were not specifically designed to study birth defects, but efforts to utilize such prospectively collected health care data can still be desirable with respect to costs, numbers of pregnancies included, validity (e.g., no recall bias) and generalizability (i.e., population-based). Nowadays, with the new surveillance systems established, epidemiological studies may not only be as valid but also much more efficient than clinical trials to identify risk or preventive factors for human birth defects.

6. What epidemiological methods are available and/or best?

Strong risk factors can be identified with crude simple epidemiologic methods.26 To rule out strong teratogenic effects (e.g., over 20% risk of malformations after prenatal exposure to thalidomide), enrollment of 100 exposed pregnancies in a simple uncontrolled cohort might suffice. This is because the effect of major teratogens is so large that it overwhelms the potential impact of common methodological biases on relative risks. However, weaker factors are more difficult to identify, and will require larger samples and accurate estimates, i.e., carefully designed studies. Validity is crucial for modest effects.

For these modest risks it is important to stick to the following “good practice” principles: I) Consider specific birth defects, II) consider specific factors (e.g., individual drugs), III) focus on the etiologically relevant gestational period, IV) obtain accurate measures of exposure and outcome, V) enroll enough sample size to attain sufficient statistical power, VI) avoid preferential publication in the context of multiple comparisons, VII) replicate studies to confirm or refute initial findings, VIII) write a detailed protocol (well-designed study, well-specified comparisons, appropriate analytic plan, etc.) that could be registered or shared, IX) careful publication (expose and discuss limitations, sensitivity analysis that quantify uncertainty, rational reporting and interpretation of scientific evidence), and X) transparent communication to stakeholders.

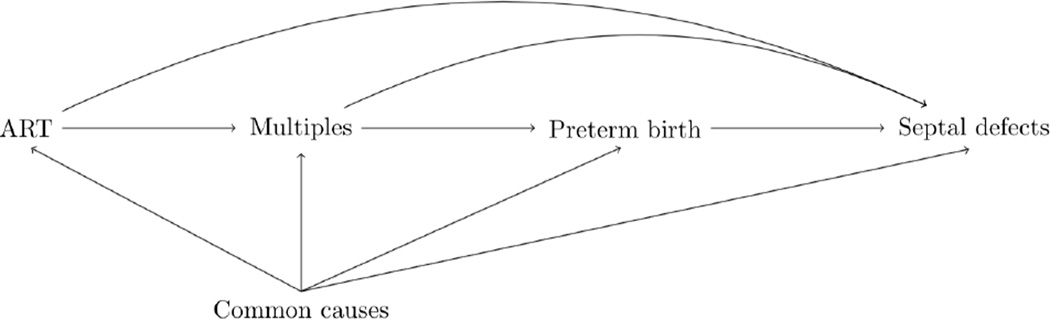

In addition to these principles, we may sometimes need to implement modern epidemiologic approaches. For instance, to avoid selection bias (e.g. by not adjusting for intermediate variables), evaluate direct and indirect effects (e.g., mediation analyses), or reduce confounding (e.g., propensity scores or inverse probability weighting). As an example, modern causal approaches could help us understand the role of plurality and prematurity on the effect of assisted reproduction technology (ART) on certain birth defects (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Example of a direct acyclic graph (DAG) to apply causal thinking to birth defects. These causal networks can help us identify confounders (common causes) and mediators (multiples and preterm birth) of the exposure association to (specific) birth defects.

The DAG’s validity depends on the identification of the correct relationship between the factors (nodes) and inclusion of all potential common causes of the exposure and outcome of interest. Vital knowledge to inform the DAGs will often originate from a broad range of disciplines, from genetics to anthropology. Epidemiological studies can benefit from other approaches indirectly (i.e., using their results to inform hypotheses and designs) and directly (e.g., incorporating genetic and epigenetic testing). Therefore, interdisciplinary collaboration and integration of different approaches is essential for the understanding of causes and predictors of human birth defects.

In conclusion, all epidemiological studies should keep in mind some basic principles; some may need to consider advanced methods. We believe that epidemiological research is necessary to understand the origins of birth defects, to predict them and to prevent them. However, it is not sufficient. Interdisciplinary collaborations will help move the field forward on more solid foundations.

7. Counter argument: limitations of epidemiological studies

While the prevention of NTDs is a success story, it may not necessarily be representative for other types of birth defects. Before the role of folic acid in NTD prevention was discovered, great variation in the occurrence of NTDs both over time and geographic areas had been described. Temporal trends and regional clusters would not be observed for completely stochastic events, thus pointing to the presence of one or more determinants that explained the variability. Further indications of an environmental influence came from observations that migrants acquired the risk in their new country of residence. In contrast to NTDs, most other birth defects show less variation in their occurrence across time and space. To infer from this observation alone that their occurrence is mostly stochastic, may however be an oversimplification.

A major challenge to study birth defects in pregnancy cohorts is the right truncation of the cohort by the spontaneous abortion and therapeutic termination of pregnancies after prenatal diagnosis of a congenital malformation. The total risk of miscarriage is 12 to 15 percent in women at their healthiest years of reproduction (age 25 to 35), and it is reasonable to expect that severe and lethal malformations are common reasons for spontaneous abortions. In Europe, about 4% of pregnancies are terminated after prenatal diagnosis of birth defects and 18% of all fetuses with malformations are terminated following prenatal screening.37 The proportion of terminations varies among specific defects,38 and among populations. Thus, the commonly quoted prevalence of malformations at birth of around 3% does not reflect the incidence of malformations during embryo development. Inability to measure the true incidence can have important consequences for etiological studies of birth defects, particularly if the exposure influences the degree of selection (a problem not even randomized controlled trials can solve).

From a methodological standpoint, an optimal study design would allow consideration of all fetuses, terminated or not. For a majority of miscarriages however, pathological analysis will never be feasible, as they may not even lead to a medical procedure. Those that occur under medical supervision are still unlikely to undergo diagnostic scrutiny with respect to specific type of defect(s). If studies generally need to be specific to a given defect to provide useful etiological information, inclusion of miscarriages would only add noise due to loss of specificity. If we believe that most teratogens influence specific processes, they may also mostly produce specific birth defects. Again speculative, this could imply that stochastic events, including chromosomal aberrations, will in comparison be responsible for a greater portion of wide-striking (multi-organ) disruptions, which are not compatible with life. If so, spontaneous abortions would represent a larger part of the stochastic quota and would if included rather lead to more noise in the quest to find causal factors. Also from a public health perspective, miscarriages - sometimes not even noticed by the woman - and major birth defects may be completely different outcomes. While fertility and fetal viability are inarguably important, we may as a society be most interested in birth defects among those who survive the first trimester.

8. Conclusions

In summary, to quantify absolute risk in humans and inform couples based on their genetic and non-genetic characteristics we need prediction models based on data from a large number of humans (i.e., epidemiological studies). To identify causes of birth defects that may lead to prevention of cases in humans we need causal inference thinking informed by data from a large number of humans (i.e. epidemiological studies). Epidemiologic approaches can be valuable for the identification of both new teratogens and the influence of genetic determinants. Thereby they can further our understanding not only on currently unknown risk factors but also on known ones. To identify potential new teratogens we have learnt from the thalidomide conundrum that we need to be proactive. To further our understanding of known risk factors, epidemiologic studies have been crucial to understand the relevance of folic acid pathways for birth defects. We learnt from folic acid that epidemiological plausibility can support biological findings as much as biological plausibility can support epidemiological ones. Although our aim has been to discuss the role of epidemiological studies, we also note that models from basic sciences and animal studies must be used to guide the design of epidemiologic studies. Hence we conclude that yes, modern epidemiologic approaches are invaluable to furthering our understanding of risk factors for human birth defects. However, translational approaches and interdisciplinary collaborations will also be essential to further our knowledge.

Acknowledgements

This work was inspired by the discussion at a workshop on “Developing an Interdisciplinary Research Agenda for Genetics of Birth Defects” held at the US National Institutes of Health in 2014. The authors wish to acknowledge Dr Allen Wilcox, who provided vital intellectual content both as discussant during the workshop and through revision of an early draft of the paper.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The views expressed in this commentary are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the US National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of Interest

AS. Oberg and S Hernandez-Diaz declare no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

- 1.Honein MA, Paulozzi LJ, Cragan JD, Correa A. Evaluation of selected characteristics of pregnancy drug registries. Teratology. 1999;60:356–364. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199912)60:6<356::AID-TERA8>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control. Economic cost of birth defects and cerebral palsy- United States, 1992. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report. 1995;44(37):694–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Global Health Statistics. Harvard: World Health Organization; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson K, Holmes LB. Malformations due to presumed spontaneous mutations in newborn infants. New England Journal of Medicine. 1989;320(1):19–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198901053200104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elwood M, Little J, Elwood H. Epidemiology and control of neural tube defects. Vol. 20. New York: Oxford university press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lie RT, Wilcox AJ, Skjaerven R. A population-based study of the risk of recurrence of birth defects. The New England journal of medicine. 1994 Jul 7;331(1):1–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407073310101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skjaerven R, Wilcox AJ, Lie RT. A population-based study of survival and childbearing among female subjects with birth defects and the risk of recurrence in their children. The New England journal of medicine. 1999 Apr 8;340(14):1057–1062. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904083401401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christensen K, Mitchell LE. Familial recurrence-pattern analysis of nonsyndromic isolated cleft palate--a Danish Registry study. Am J Hum Genet. 1996 Jan;58(1):182–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen K, Schmidt MM, Vaeth M, Olsen J. Absence of an environmental effect on the recurrence of facial-cleft defects. The New England journal of medicine. 1995 Jul 20;333(3):161–164. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507203330305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burn J, Brennan P, Little J, et al. Recurrence risks in offspring of adults with major heart defects: results from first cohort of British collaborative study. Lancet. 1998 Jan 31;351(9099):311–316. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)06486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oyen N, Boyd HA, Poulsen G, Wohlfahrt J, Melbye M. Familial recurrence of midline birth defects--a nationwide danish cohort study. American journal of epidemiology. 2009 Jul 1;170(1):46–52. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oyen N, Poulsen G, Boyd HA, Wohlfahrt J, Jensen PK, Melbye M. Recurrence of congenital heart defects in families. Circulation. 2009 Jul 28;120(4):295–301. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.857987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pradat P. Recurrence risk for major congenital heart defects in Sweden: a registry study. Genet Epidemiol. 1994;11(2):131–140. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370110204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmes LB, Harvey EA, Coull BA, et al. The teratogenicity of anticonvulsant drugs. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344:1132–1138. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104123441504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hernandez-Diaz S, Smith CR, Shen A, et al. Comparative safety of antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy. Neurology. 2012 May 22;78(21):1692–1699. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182574f39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davidson DL. Letter to the editor. Discordant twins for neural tube defect on treatment with sodium valproate. Seizure. 2002 Oct;11(7):445. doi: 10.1053/seiz.2002.0704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell E, Devenney E, Morrow J, et al. Recurrence risk of congenital malformations in infants exposed to antiepileptic drugs in utero. Epilepsia. 2013 Jan;54(1):165–171. doi: 10.1111/epi.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vajda FJ, O'Brien TJ, Lander CM, Graham J, Roten A, Eadie MJ. Teratogenesis in repeated pregnancies in antiepileptic drug-treated women. Epilepsia. 2013 Jan;54(1):181–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell AA. Special considerations in studies of drug-induced birth defects. In: Strom BL, editor. Pharmacoepidemiology. Third ed. John Wiley & Sons; 2000. pp. 750–763. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Holmes LB. Human teratogens: update 2010. Birth defects research. Part A, Clinical and molecular teratology. 2011 Jan;91(1):1–7. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20748. This manuscript reviews some of the known human teratogens, data sources where they can be identified and gaps of information. The author points out our inability to explain and predict teratogenic effects.

- 21.Wilson JG. Evaluation of human teratologic risk in animals. In: Lee DH, Hewson EW, Okun D, editors. Environment and birth defects. First ed. New York and London: Academic Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laurence KM, James N, Miller MH, Tennant GB, Campbell H. Double-blind randomised controlled trial of folate treatment before conception to prevent recurrence of neural-tube defects. British medical journal. 1981 May 9;282(6275):1509–1511. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6275.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McBride WG. Thalidomide and congenital abnormalities. The Lancet. 1961 Dec 16;278(7216):1358. 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burley DM, Lenz W. Thalidomide and congential abnormalities. The Lancet. 1962 7223 Feb 3;279:271–272. 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lenz W, Pfeiffer RA, Kosenow W, Hayman DJ. Thalidomide and congentical abnormalities. The Lancet. 1962 7219 Jan 6;279:45–46. 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mitchell AA. Systematic Identification of Drugs That Cause Birth Defects — A New Opportunity. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349(26):2556–2559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb031395. The author proposes a surveillance system for teratogens and reviews the main study designs available to provide valid information, i.e., cohorts and case–control designs. The role, advantages and limitations of each epidemiological approach are discussed.

- 27.Meador KJ, Pennell PB, Harden CL, et al. Pregnancy registries in epilepsy: a consensus statement on health outcomes. Neurology. 2008 Sep 30;71(14):1109–1117. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000316199.92256.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.U.S Department of Health Education and Welfare PHS, National Institutes of Health. The Collaborative Perinatal Stufy of the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke: The Women and Their Pregnancies. 1972:73–379. DHEW Publication No. (NIH)

- 29.Heinonen O, Slone D, Shapiro S. Birth Defects and drugs in pregnancy. Littleton, Massachusetts: Publishing Sciences Group; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lammer EJ, Chen DT, Hoar RM, et al. Retinoic acid embryopathy. The New England journal of medicine. 1985 Oct 3;313(14):837–841. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198510033131401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Werler MM, Louik C, Shapiro S, Mitchell AA. Prepregnant weight in relation to risk of neural tube defects. Jama. 1996 Apr 10;275(14):1089–1092. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03530380031027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mulinare J, Cordero JF, Erickson JD, Berry RJ. Periconceptional use of multivitamins and the occurrence of neural tube defects. Jama. 1988 Dec 2;260(21):3141–3145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milunsky A, Jick H, Jick SS, et al. Multivitamin/folic acid supplementation in early pregnancy reduces the prevalence of neural tube defects. Jama. 1989 Nov 24;262(20):2847–2852. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.20.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prevention of neural tube defects: results of the Medical Research Council Vitamin Study. MRC Vitamin Study Research Group. Lancet. 1991 Jul 20;338(8760):131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wettermark B, Zoega H, Furu K, et al. The Nordic prescription databases as a resource for pharmacoepidemiological research--a literature review. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety. 2013 Jul;22(7):691–699. doi: 10.1002/pds.3457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmsten K, Huybrechts KF, Mogun H, et al. Harnessing the Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) to Evaluate Medications in Pregnancy: Design Considerations. PloS one. 2013;8(6):e67405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dolk H, Loane M, Garne E. The prevalence of congenital anomalies in Europe. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2010;686:349–364. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-9485-8_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Svensson E, Ehrenstein V, Norgaard M, et al. Estimating the Proportion of All Observed Birth Defects Occurring in Pregnancies Terminated by a Second-trimester Abortion. Epidemiology. 2014 Nov;25(6):866–871. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000163. Using data from the Danish medical registries, the authors quantified the proportion of all fetuses with birth defects terminated in pregnancy. The proportion of birth defects terminated, i.e., unobserved at birth, varied by type of defect. The proportion was almost 50% for defects of the nervous system, but it was less than 10% for most types of birth defects.