Abstract

Objectives

To characterize pathological and cancer-specific outcomes of surgically resected cystic renal tumors and to identify clinical or radiographic features associated with these outcomes.

Methods and materials

All patients at our institution who underwent radical or partial nephrectomy for complex renal cystic masses between 2004 and 2011 with available computed tomographic imaging were included. The Bosniak score was determined, as were 10 specific radiographic characteristics of renal cysts in patients with preoperative imaging available for review. These characteristics were correlated with cystic mass histopathology. Recurrence-free survival after surgery was determined.

Results

Overall, 133 patients underwent renal surgery for complex cystic lesions, 89 (67%) of whom had malignant lesions. Malignancy risk increased with Bosniak score (P ≤ 0.01) and presence of mural nodules (P = 0.01). Most (63%) malignancies demonstrated clear cell histology. The papillary renal cell carcinomas (25%) exhibited lower enhancement levels (P = 0.04) and were less often septated (P < 0.01). Of the malignancies, 79% were low stage (pT1), and 73% were Fuhrman grade 1 or 2. Large cyst size was associated with advanced tumor stage (P = 0.05). Neither Bosniak score nor any other radiographic parameter was associated with Fuhrman grade. In 70 patients with a median follow-up of 43 months, only 1 (1.4%) developed disease recurrence.

Conclusions

Most cystic renal malignancies are low-stage, low-grade lesions. Papillary renal cell carcinomas account for nearly a quarter of cystic renal malignancies and have unique radiographic characteristics. Disease recurrence after surgical resection is rare. These findings suggest an indolent behavior for cystic renal tumors, and these lesions may be amenable to active surveillance.

Keywords: Kidney, Renal cell carcinoma, Cysts, X-ray computed tomography

1. Introduction

The incidence of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) has increased in the last decade [1]. This increased incidence is partially due to the widespread use of abdominal cross-sectional imaging leading to the frequent detection of asymptomatic renal masses. Although the majority of these masses are solid lesions, approximately 6% of these incidentally detected masses are cystic renal cancers [2].

Although the pathological and cancer-specific outcomes for solid renal masses have been studied extensively [3–5], these characteristics for cystic masses are less well characterized [6]. Given the paucity of data regarding cystic renal masses, counseling patients with asymptomatic cystic renal lesions can be difficult. The Bosniak score is well established in characterizing the malignant potential of cystic renal lesions [7,8]; however, it is unclear whether there is an association between Bosniak score and other pathological outcomes such as histologic subtype, pathological stage, and Fuhrman grade. It is also unclear which specific radiographic characteristics of cystic renal lesions are most strongly associated with the risk of malignancy and other pathologic outcomes, which may be particularly important given the uncertainties inherent in percutaneous biopsy of cystic renal lesions.

A growing body of literature supports active surveillance as an initial management strategy for small renal masses, especially those thought to have relatively indolent behavior with minimal potential for metastases [9]. Identification of clinical or radiographic characteristics associated with indolent behavior of cystic renal lesions would allow the clinician to better differentiate lesions that can be managed expectantly from those with greater malignant potential that warrant immediate intervention.

In the current study, we aimed to describe the pathological characteristics and cancer-specific outcomes of cystic renal lesions removed owing to concern for malignancy. Furthermore, we sought to retrospectively identify clinical or radiographic characteristics associated with these specific pathological outcomes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study cohort

A retrospective analysis of our institutional kidney cancer database was performed to identify subjects who underwent either radical or partial nephrectomy for a cystic renal lesion concerning for malignancy between 2004 and 2011. Study approval was obtained by our institutional review board. Patients with known hereditary renal tumor syndromes, polycystic kidney disease, and renal failure– associated renal cystic disease were excluded. A total of 133 patients were identified. Of these, 49 (36.8%) had detailed 3- or 4-phase preoperative computed tomographic (CT) imaging (precontrast as well as early and delayed post–intravenous contrast phases) available for rereview.

For patients with available preoperative imaging, scans were rereviewed by a single body imaging fellowship– trained CT attending radiologist (P.T.J.) blinded to diagnosis, who confirmed the presence of a cystic lesion, defined as a renal lesion with a wall surrounding some degree of fluid components. At the discretion of the radiologist, lesions that appeared to be solid lesions with large areas of necrosis were excluded. Each case was assigned a Bosniak score, performed by consensus between the same radiologist and a highly experienced attending radiologist (E.K.F.) for equivocal cases [8]. For patients in whom preoperative imaging was not available for rereview, the Bosniak score was determined by the radiology report or by the clinician's interpretation of the imaging at the time of the original clinic visit.

In patients with available preoperative imaging, CT images were rereviewed for the following 10 detailed radiographic characteristics: percent of lesion cystic vs. solid, presence of septations, character (thick vs. thin) of septations, presence of a mural nodule, presence of necrosis, presence of calcifications, 3-dimensional size of cyst, 3-dimensional size of mural nodule, maximum wall thickness, and density of any cystic or solid components on precontrast and arterial phase (i.e., lesion enhancement). These characteristics were not assessed in the subset of patients in whom preoperative imaging was not available for rereview.

2.2. Pathological analysis

Pathological characteristics after either partial or radical nephrectomy were determined by chart review. These characteristics included tumor histologic subtype, pathological stage, and Fuhrman grade. Per convention, Fuhrman grade was not determined for chromophobe RCC [10].

Univariate associations of demographic characteristics and clinical parameters with pathological outcomes were then determined using the chi-squared test. Associations between Bosniak score and pathological outcomes were similarly determined.

In the subset of patients with available preoperative imaging, the chi-squared test was used to determine univariate associations between the 10 detailed radiographic characteristics and pathological outcomes. Several patients did not have a full 3-phase renal protocol CT performed preoperatively, as not all of the scans were performed at our institution. Thus, certain radiographic parameters could not be assessed in all patients, precluding a multivariable analysis investigating associations between radiographic characteristics and pathological outcomes.

2.3. Survival analysis

Tumor recurrence data were ascertained from the Johns Hopkins Hospital and Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center cancer registries, which prospectively collect annual oncological follow-up data on all patients with cancer treated at these institutions. Recurrence was defined as detection of a nodal or distant metastasis. Recurrence-free survival was determined for patients with ≥6 months of available follow-up data.

3. Results

Overall, 133 patients met the study inclusion criteria; all had pathology reviewed at our institution (100%), and 49 (37%) had preoperative CT imaging available for institutional radiologic rereview. Patient demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. There were 80 men (60%) and 53 women (40%). Median patient age was 57.0 years (interquartile range = 19.3 y). Of the 133 lesions, 44 (33%) were benign and 89 (67%) were malignant. Of the 44 benign lesions, there were 40 (91%) simple cysts and 4 (9%) mixed epithelial and stromal tumors. These distributions were similar for the subset of patients with available preoperative imaging.

Table 1.

Patient demographic characteristics and malignancy of cystic lesions

| All patients n (%) |

Patients with preoperative CT available for review n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 80 (60) | 30 (61) |

| Female | 53 (40) | 19 (39) |

| Age, y | ||

| <50 | 40 (30) | 10 (20) |

| 50–60 | 38 (29) | 12 (25) |

| >60 | 55 (41) | 27 (55) |

| Pathology of cystic lesion | ||

| Benign | 44 (33) | 12 (24) |

| Malignant | 89 (67) | 37 (76) |

| Total | 133 | 49 |

3.1. Pathology

Table 2 shows the histology, pathological stage, and Fuhrman grade of the malignant lesions. Most malignancies were clear cell RCCs (63%), although there was a significant percentage of papillary RCCs (25%). Overall, 79% of tumors were low-stage lesions (pT1), and 73% of tumors were Fuhrman grade 1 or 2. Two patients (2.2%) had radiographic evidence of metastatic disease at the time of presentation from cystic clear cell RCC.

Table 2.

Pathological characteristics of malignant cystic renal lesions

| All patients n (%) |

Patients with preoperative CT available for review n (%) |

|

| Tumor histology | ||

| Clear cell RCC | 56 (63) | 21 (57) |

| Papillary RCC | 22 (25) | 9 (24) |

| Chromophobe RCC | 6 (7) | 2 (5) |

| Clear cell papillary RCC | 2 (2) | 2 (5) |

| RCC, unclassifiable | 1 (1) | 1 (3) |

| Xp11 translocation RCC | 1 (1) | 1 (3) |

| Liposarcoma | 1 (1) | 1 (3) |

| Total | 89 | 37 |

| Pathological T stage | ||

| pT1a | 46 (52) | 21 (57) |

| pT1b | 24 (27) | 6 (16) |

| pT2a | 4 (5) | 2 (5) |

| pT2b | 3 (3) | 3 (8) |

| pT3a | 9 (10) | 4 (11) |

| pT3b | 1 (1) | 1 (3) |

| Unknown | 2 (2) | 0 |

| Total | 89 | 37 |

| Fuhrman gradea | ||

| 1 | 10 (12) | 4 (12) |

| 2 | 50 (61) | 18 (53) |

| 3 | 19 (23) | 11 (32) |

| 4 | 1 (1) | 1 (3) |

| Unknown | 2 (3) | 0 |

| Total | 82 | 34 |

Fuhrman grading not applicable to chromophobe.

No significant associations were observed between patient sex and the likelihood of malignancy (P = 0.19), tumor histology (P = 0.41), or Fuhrman grade (P = 0.78). When comparing pathological stage of malignant lesions between men and women, there was a trend toward more advanced stage (pT2/T3) lesions in men, although this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.07). Compared with benign lesions, there was a trend toward older age in patients with malignant cysts (57.9 vs. 53.4 y, P = 0.07). Advanced age was significantly associated with papillary vs. clear cell histology (mean age 63.3 vs. 55.7 y, P = 0.02) but there was no association between patient age and pathological stage (P = 0.46) or Fuhrman grade (P = 0.74).

3.2. Radiographic correlates

Table 3 shows the association between the Bosniak score and the pathological outcomes of interest. As expected, the likelihood of malignancy increased with increasing Bosniak score (P < 0.01). There were however no significant associations between Bosniak score and either histologic subtype (P = 0.71), pathological stage (P = 0.83), or Fuhrman grade (P = 0.35).

Table 3.

Association of Bosniak score with pathological outcomes

| Bosniak score | Malignancy | Histologic subtype | Pathological T stage | Fuhrman grade | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | Malignant | P | Clear cell RCC | Papillary RCC | P | pT1/T2 | pT3 | P | Grade 1/2 | Grade 3/4 | P | |

| II | 14 (88%) | 2 (12%) | <0.01 | 2 (100%) | 0 | 0.71 | 2 (100%) | 0 | 0.83 | 2 (100%) | 0 | 0.35 |

| IIf | 4 (67%) | 2 (33%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | 2 (100%) | 0 | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | ||||

| III | 11 (34%) | 21 (66%) | 14 (74%) | 5 (26%) | 19 (90%) | 2 (10%) | 17 (85%) | 3 (15%) | ||||

| IV | 9 (15%) | 50 (85%) | 29 (69%) | 13 (31%) | 42 (86%) | 7 (14%) | 30 (68%) | 14 (32%) | ||||

Table 4 shows the associations between detailed radiographic characteristics and pathological findings in patients whose preoperative imaging was available for rereview. Patients with mural nodules were more likely to have malignant tumors (P = 0.01). There was a trend toward a higher risk of malignancy in lesions with larger solid components (P = 0.07). There were no significant associations between any of the other radiographic parameters and the likelihood of malignancy.

Table 4.

Associations of radiographic parameters with pathological outcomes

| Malignancy | Histologic subtype | Pathological stage | Fuhrman grade | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | Malignant | P | Clear cell RCC | Papillary RCC | P | pT1/pT2 | pT3 | P | Grade 1/2 | Grade 3/4 | P | |

| Percent cystic | ||||||||||||

| >75% | 9 (36%) | 16 (64%) | 0.07 | 9 (69%) | 4 (31%) | 0.66 | 14 (88%) | 2 (12%) | 0.57 | 9 (60%) | 6 (40%) | 0.28 |

| ≤75% | 2 (11%) | 16 (89%) | 10 (77%) | 3 (23%) | 12 (80%) | 3 (20%) | 11 (79%) | 3 (21%) | ||||

| Septations present | ||||||||||||

| No | 3 (17%) | 15 (83%) | 0.24 | 4 (36%) | 7 (64%) | <0.01 | 14 (93%) | 1 (7%) | 0.22 | 7 (54%) | 6 (46%) | 0.47 |

| Yes | 9 (32%) | 19 (68%) | 14 (88%) | 2 (12%) | 14 (78%) | 4 (22%) | 12 (67%) | 6 (33%) | ||||

| Septation quality | ||||||||||||

| Thin | 3 (50%) | 3 (40%) | 0.10 | 2 (100%) | 0 | 0.57 | 3 (100%) | 0 | 0.53 | 2 (67%) | 1 (33%) | 1.00 |

| Thick | 5 (24%) | 16 (76%) | 12 (86%) | 2 (14%) | 11 (73%) | 4 (27%) | 10 (67%) | 5 (33%) | ||||

| Mural nodule | ||||||||||||

| No | 8 (44%) | 10 (56%) | 0.01 | 4 (57%) | 3 (43%) | 0.54 | 10 (100%) | 0 | 0.11 | 4 (44%) | 5 (56%) | 0.22 |

| Yes | 3 (11%) | 24 (89%) | 14 (70%) | 6 (30%) | 18 (78%) | 5 (22%) | 15 (68%) | 7 (32%) | ||||

| Mural nodule size | ||||||||||||

| ≤2 cm | 1 (9%) | 10 (91%) | 0.95 | 7 (78%) | 2 (22%) | 0.89 | 7 (70%) | 3 (30%) | 0.26 | 6 (60%) | 4 (40%) | 0.42 |

| >2 cm | 1 (8%) | 11 (92%) | 6 (75%) | 2 (25%) | 9 (90%) | 1 (10%) | 7 (78%) | 2 (22%) | ||||

| Necrosis | ||||||||||||

| No | 2 (11%) | 16 (89%) | 0.93 | 8 (73%) | 3 (27%) | 0.44 | 14 (88%) | 2 (12%) | 0.16 | 10 (71%) | 4 (29%) | 0.32 |

| Yes | 1 (10%) | 9 (90%) | 7 (88%) | 1 (12%) | 5 (63%) | 3 (37%) | 4 (50%) | 4 (50%) | ||||

| Calcifications | ||||||||||||

| No | 7 (22%) | 25 (78%) | 0.43 | 15 (75%) | 5 (25%) | 0.12 | 20 (83%) | 4 (17%) | 0.78 | 14 (61%) | 9 (39%) | 0.94 |

| Yes | 4 (33%) | 8 (67%) | 3 (43%) | 4 (57%) | 7 (88%) | 1 (12%) | 5 (63%) | 3 (37%) | ||||

| Lesion diameter | ||||||||||||

| ≤4 cm | 6 (30%) | 14 (70%) | 0.46 | 7 (64%) | 4 (36%) | 0.56 | 14 (100%) | 0 | 0.05 | 8 (67%) | 4 (33%) | 0.86 |

| >4 cm | 6 (21%) | 23 (79%) | 14 (74%) | 5 (26%) | 17 (77%) | 5 (23%) | 14 (64%) | 8 (36%) | ||||

| Maximum wall thickness | ||||||||||||

| <1.5 cm | 2 (11%) | 17 (89%) | 0.22 | 11 (79%) | 3 (21%) | 0.63 | 15 (88%) | 2 (12%) | 0.24 | 10 (67%) | 5 (33%) | 0.86 |

| ≥1.5 cm | 4 (27%) | 11 (73%) | 7 (70%) | 3 (30%) | 7 (70%) | 3 (30%) | 7 (70%) | 3 (30%) | ||||

| Enhancement | ||||||||||||

| ≤50 HU | 3 (25%) | 9 (75%) | 0.62 | 3 (38%) | 5 (63%) | 0.04 | 7 (88%) | 1 (12%) | 0.38 | 4 (50%) | 4 (50%) | 0.82 |

| >50 HU | 2 (17%) | 10 (83%) | 7 (88%) | 1 (12%) | 7 (70%) | 3 (30%) | 4 (44%) | 5 (56%) | ||||

Given the small numbers of chromophobe RCC, clear cell papillary RCC, Xp11 translocation RCC, and liposarcoma, we were only able to test for radiographic associations with pure clear cell or papillary histology. Cystic lesions without septations were more likely to represent papillary RCC compared with those with septations (P < 0.01). Likewise, hypoenhancing lesions were more often papillary as compared with clear cell RCC (P = 0.04). The other radiographic parameters we investigated were not found to have significant associations with histologic RCC subtype. Cystic renal lesions greater than 4 cm in diameter were more likely to be advanced stage (pT3) compared with smaller lesions (P = 0.05). Otherwise, there were no significant associations between the other detailed radiographic parameters and pathological stage. Likewise, no significant associations were observed between radiographic characteristics and Fuhrman grade.

3.3. Survival analysis

More than 6 months of follow-up data were available for 70 of 89 patients (78.7%) with malignant renal lesions, allowing for the calculation of recurrence-free survival in these patients. Mean and median follow-up times in these patients were 46 and 43 months, respectively. Only 1 patient (1.4%) had recurrence, at 21 months postoperatively, from a pT3a Fuhrman grade 3 clear cell cystic RCC. Another 2 patients had metastatic disease at the time of surgery and thus were never considered disease free. Their primary lesions proved to be pT3a Fuhrman grade 2 clear cell RCC and pT3b Fuhrman grade 4 clear cell RCC.

4. Comment

Cystic RCC accounts for approximately 5% to 7% of all malignant renal lesions [2]. In the current study, we show that most surgical cystic renal malignancies are low-stage, low-grade lesions and that disease recurrence is rare following surgical resection. On pathological analysis, only 11% of cystic malignancies were nonorgan confined and only 24% were Fuhrman grade 3 or 4. Furthermore, at a median follow-up of 43 months, only a single patient developed disease recurrence. These findings argue for a relatively indolent clinical behavior for cystic, as opposed to solid, renal malignancies and should aid the practitioner in counseling patients with complex cystic renal lesions.

Others have similarly described the favorable characteristics of cystic renal masses. In a study of 39 cystic renal lesions, Han et al. [6] reported a lesser stage and grade for cystic tumors compared with solid clear cell RCCs. Furthermore, Webster et al. [11] suggested that cancer-specific survival is superior in patients with cystic compared with solid RCCs. At present, although the pathological characteristics of cystic malignancies are in evolution in the pathology literature, they appear to represent a less aggressive form of lesion than a comparable solid one [6,11].

The distribution of histologic subtypes in the current study further argues for the indolent behavior of cystic RCCs. Overall, 25% of malignancies were noted to have papillary histology, a prevalence that exceeds the 10% to 15% rate of papillary lesions reported in series of solid renal masses [12,13]. This high prevalence of papillary malignancies is comparable to the 25.9% to 33.3% rate of papillary histology reported in prior studies of surgically excised complex renal cysts [14,15]. Compared with lesions with clear cell histology, papillary RCCs are thought to exhibit less malignant behavior [16,17], further suggesting that cystic renal malignancies are on average less aggressive than their solid counterparts.

At our institution, active surveillance is offered to patients with small solid renal masses, especially those with advanced age, poor performance status, or medical comorbidities including chronic kidney disease [18]. Active surveillance of these lesions appears to be safe, with <2% of patients progressing to metastatic disease in the published literature [19–23]. The outcomes in this study suggest an indolent behavior for most cystic renal lesions, arguing that these patients may also be ideal candidates for active surveillance.

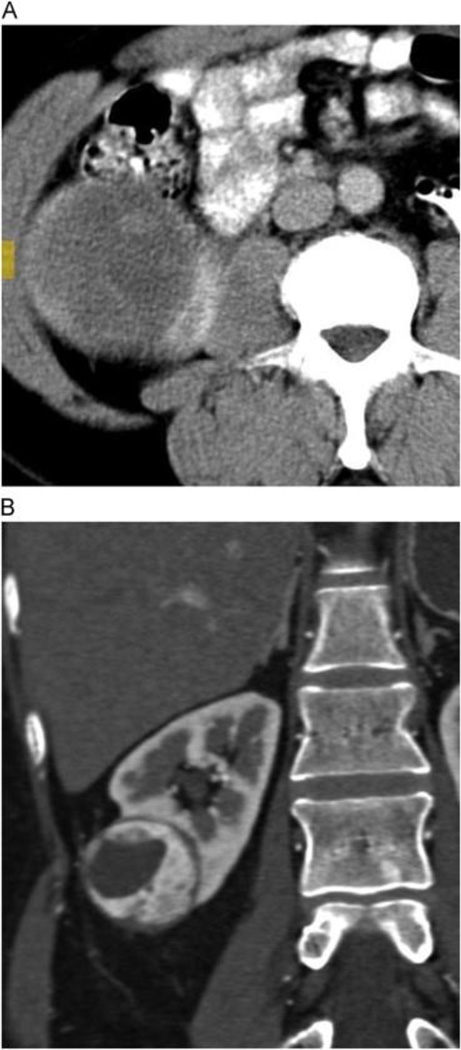

The Bosniak score is a well-established system used to assess the malignant potential of cystic renal lesions. We confirmed the strong association between Bosniak score and the likelihood of malignancy, but failed to find an association between Bosniak score and tumor histology, stage, or grade. Few studies have looked beyond the Bosniak score to investigate specific radiographic characteristics of complex renal cysts and their associations with malignancy rate and other pathological outcomes. Of the characteristics that have been studied, enhancement of the cystic septal or nodular component has been most closely associated with the likelihood of malignancy [24,25]. The current study does not address this association, as enhancement of a mural nodule upstages a lesion to Bosniak class IV, which in turn confers a very high risk of malignancy on its own. Instead, we looked at mural nodules in terms of both presence/absence and size, and found that the simple presence of a mural nodule was a strong predictor of malignancy in and of itself (Fig. 1). Additionally, there was a trend toward a higher rate of malignancy in cystic lesions with larger solid components compared with those that were primarily cystic. These observations suggest that not all radiographic features of lesion complexity should be given equal weight when determining the malignancy potential of cystic renal masses.

Fig. 1.

A 78-year-old man with complex cystic left renal mass, pathologically proven as Fuhrman grade 2 clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Precontrast (A) and corticomedullary phase post-contrast (B) enhanced images show highly vascular mural nodules that enhanced as high as 243 Hounsfield units on the arterial phase. (Color version of figure is available online.)

In studies of solid renal lesions, it has been shown that papillary RCCs are hypoenhancing relative to lesions with clear cell histology [26]. In this series, cystic lesions without septations and those that were hypoenhancing were more often papillary as compared with clear cell RCCs (Fig. 2). Although additional investigation is needed to confirm these potential associations, these radiographic characteristics may nevertheless assist clinicians in better characterizing complex renal cysts before surgery.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of wall enhancement between papillary and clear cell tumors. (A) A 59-year-old man with cystic mass arising from right kidney. Axial corticomedullary phase IV contrast-enhanced CT image shows a thick-walled mass with only moderate enhancement of wall and septations. Pathology revealed papillary renal cell, Fuhrman grade III. (B) A 60-yearold woman with complex cystic and solid mass arising from lower pole right kidney. Coronal images from corticomedullary phase IV contrast-enhanced CT image shows thick, hypervascular wall, with marked enhancement during arterial phase, consistent with clear cell variant, Fuhrman grade II. (Color version of figure is available online.)

The current study is not without limitations. In this analysis, renal cysts were defined by radiographic, as opposed to pathological, criteria. When defined pathologically, the prevalence of cystic RCC is as high as 30% [27], compared with only 5% to 7% when defined radiographically [2]. Thus, many RCCs with smaller cystic components may not have been captured in this analysis. However, we feel that a radiographic definition is more helpful in clinical practice, as complex cystic lesions are initially diagnosed based on imaging studies. Thus, the data in this study are pertinent to the clinician evaluating radiographically detected complex renal cysts and can assist in determining a management strategy for these lesions.

Additionally, this retrospective review includes only patients treated surgically for complex renal cysts; those managed with surveillance or ablation are not included. This introduces selection bias toward a potentially higher frequency of malignancy that might influence our findings. Furthermore, although we performed central radiologic rereview, we did not centrally rereview all pathological specimens, instead relying on the fact that all pathology reports were issued in standard fashion by one of our institutional experts in genitourinary pathology. Finally, owing to the time span evaluated, there was some variability in CT protocols, and radiographic characteristics of the cystic lesions could not be fully assessed in all patients. Specifically, not all patients had a dedicated 3-phase renal protocol CT performed preoperatively and not all of the scans were performed at our institution. This, coupled with the relatively small number of patients in the series, precluded a multivariable analysis to investigate associations between radiographic characteristics and pathological outcomes. Moreover, we tested for multiple univariate associations of radiographic parameters with pathological outcomes, which increases the possibility of identifying false-positive associations.

5. Conclusions

Most surgically resected cystic RCCs are low-stage, low-grade lesions, and the prevalence of papillary histology appears to exceed that expected in solid RCC. For patients who undergo surgical resection, disease recurrence appears to be quite rare at intermediate follow-up, although 2 patients did present with synchronous metastases related to cystic clear cell RCC. Taken together, these findings argue for a generally more indolent behavior for cystic as compared with solid RCCs. Furthermore, specific radiographic characteristics, such as the presence of a mural nodule and enhancement level of solid components, may be useful in predicting the malignancy potential and aggressiveness of cystic lesions preoperatively. These findings may aid in preoperative risk assessment of cystic renal lesions and help identify lesions that can be managed with surveillance in appropriately selected patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by the Jewett and Warburton Family Foundation Fellowship in Urologic Oncology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

References

- 1.Nguyen MM, Gill IS, Ellison LM. The evolving presentation of renal carcinoma in the United States: trends from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program. J Urol. 2006;176(6 Pt 1):2397–2400. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.144. [discussion 2400]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warren KS, McFarlane J. The Bosniak classification of renal cystic masses. BJU Int. 2005;95:939–942. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isbarn H, Karakiewicz PI. Predicting cancer-control outcomes in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Curr Opin Urol. 2009;19:247–257. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e32832a0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lane BR, Kattan MW. Prognostic models and algorithms in renal cell carcinoma. Urol Clin North Am. 2008;35:613–625. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2008.07.003. (vii). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rini BI, Campbell SC, Escudier B. Renal cell carcinoma. Lancet. 2009;373:1119–1132. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han KR, Janzen NK, McWhorter VC, et al. Cystic renal cell carcinoma: biology and clinical behavior. Urol Oncol. 2004;22:410–414. doi: 10.1016/S1078-1439(03)00173-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosniak MA. The current radiological approach to renal cysts. Radiology. 1986;158:1–10. doi: 10.1148/radiology.158.1.3510019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosniak MA. The use of the Bosniak classification system for renal cysts and cystic tumors. J Urol. 1997;157:1852–1853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abou Youssif T, Kassouf W, Steinberg J, et al. Active surveillance for selected patients with renal masses: updated results with long-term follow-up. Cancer. 2007;110:1010–1014. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delahunt B, Sika-Paotonu D, Bethwaite PB, et al. Fuhrman grading is not appropriate for chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:957–960. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000249446.28713.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Webster WS, Thompson RH, Cheville JC, et al. Surgical resection provides excellent outcomes for patients with cystic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Urology. 2007;70:900–904. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.05.029. [discussion 904]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck SD, Patel MI, Snyder ME, et al. Effect of papillary and chromophobe cell type on disease-free survival after nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:71–77. doi: 10.1007/BF02524349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patard JJ, Leray E, Rioux-Leclercq N, et al. Prognostic value of histologic subtypes in renal cell carcinoma: a multicenter experience. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2763–2771. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Mokadem I, Budak M, Pillai S, et al. Progression, interobserver agreement, and malignancy rate in complex renal cysts (≥Bosniak category IIF) Urol Oncol. 2014;32(24):e21–e27. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith AD, Remer EM, Cox KL, et al. Bosniak category IIF and III cystic renal lesions: outcomes and associations. Radiology. 2012;262:152–160. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leibovich BC, Lohse CM, Crispen PL, et al. Histological subtype is an independent predictor of outcome for patients with renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2010;183:1309–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teloken PE, Thompson RH, Tickoo SK, et al. Prognostic impact of histological subtype on surgically treated localized renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2009;182:2132–2136. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pierorazio PM, Hyams ES, Mullins JK, et al. Active surveillance for small renal masses. Rev Urol. 2012;14(1–2):13–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chawla SN, Crispen PL, Hanlon AL, et al. The natural history of observed enhancing renal masses: meta-analysis and review of the world literature. J Urol. 2006;175:425–431. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kouba E, Smith A, McRackan D, et al. Watchful waiting for solid renal masses: insight into the natural history and results of delayed intervention. J Urol. 2007;177:466–470. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.09.064. [discussion 470]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kunkle DA, Egleston BL, Uzzo RG. Excise, ablate or observe: the small renal mass dilemma—a meta-analysis and review. J Urol. 2008;179:1227–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.11.047. [discussion 1233–4]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mason RJ, Abdolell M, Trottier G, et al. Growth kinetics of renal masses: analysis of a prospective cohort of patients undergoing active surveillance. Eur Urol. 2011;59:863–867. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smaldone MC, Kutikov A, Egleston BL, et al. Small renal masses progressing to metastases under active surveillance: a systematic review and pooled analysis. Cancer. 2012;118:997–1006. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benjaminov O, Atri M, O'Malley M, et al. Enhancing component on CT to predict malignancy in cystic renal masses and interobserver agreement of different CT features. Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:665–672. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song C, Min GE, Song K, et al. Differential diagnosis of complex cystic renal mass using multiphase computerized tomography. J Urol. 2009;181:2446–2450. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.01.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J, Lefkowitz RA, Ishill NM, et al. Solid renal cortical tumors: differentiation with CT. Radiology. 2007;244:494–504. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2442060927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park HS, Lee K, Moon KC. Determination of the cutoff value of the proportion of cystic change for prognostic stratification of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2011;186:423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]