Abstract

Standardized uptake value (SUV) normalized by lean body mass ([LBM] SUL) is becoming a popular metric for quantitative assessment of clinical PET. Sex-specific quantitative effects of different LBM formulations on liver SUV have not been well studied.

Methods

18F-FDG PET/CT scans from 1,033 consecutive adult (501 women, 532 men) studies were reviewed. Liver SUV was measured with a 3-cm-diameter spheric region of interest in the right hepatic lobe and corrected for LBM using the sex-specific James and Janmahasatian formulations.

Results

Body weight was 71.0 ± 20.7 kg (range, 18.0–175.0 kg) and 82.9 ± 18.6 kg (range, 23.0–159.0 kg) for women and men, respectively. SUV, based on body weight, has a significantly positive correlation with weight for both women (r = 0.58, P < 0.0001) and men (r = 0.54, P < 0.0001). This correlation is reduced in men (r = 0.11, P = 0.01) and becomes negative for women (r = −0.35, P = 0.0001) with the James formulation of SUL. This negative correlation was eliminated when the very obese women (body mass index ≥ 35) were excluded from the analysis (r = 0.13, P = 0.8). The Janmahasatian formulation annuls the correlation between SUL and weight for women (r = 0.04, P = 0.4) and decreases it for men (r = 0.13, P = 0.003).

Conclusion

Hepatic correction with the more common James formulation for body lean mass breaks down and shows low SUL values in very obese patients. The adoption of the Janmahasatian formula for estimation of LBM in modern PET scanners and display workstations is recommended, in view of the increasing frequency of obesity.

Keywords: PET, FDG, SUV, SUL, LBM, gender-specific

PET/CT imaging of cancer with combined PET and CT scanners has become a standard component of diagnosis and staging in oncology (1,2). The glucose analog 18F-FDG has been shown to concentrate in tumors because of enhanced glycolysis by malignant cells (3,4). Standardized uptake value (SUV) is defined from

| Eq. 1 |

Because fat contributes to body weight (BW) but accumulates little 18F-FDG in the fasting state, SUV in obese patients is increased relatively in thinner patients (5). Using the lean body mass (LBM) correction of SUV (SUL) for obese patients was found to be a more appropriate quantitative method than BW or body surface area (6).

Normal-liver SUV has been previously proposed as a reference tissue in guidelines that included PET as part of the response criteria (7,8) because of its stability over time and in test–retest studies (9). PET Response Criteria in Solid Tumors 1.0 propose that normal-tissue 18F-FDG activity be determined in the right hepatic lobe of the liver and consists of the mean SUL in a 3-cm-diameter spheric region of interest (8).

Modern scanners use the James equation (Eq. 2), which relies on sex, height (cm), and total BW (kg), to estimate LBM (10):

| Eq. 2 |

The James formula for LBM depends on the square of the weight with a negative coefficient. The graphical representation of such a functional dependence is an inverted parabola.

Analysis of the James equations (Eq. 1) to find the peak value when the first derivative with respect to weight equals zero shows that the maximum of LBM, after which it starts declining, is reached for a body mass index (BMI) of approximately 43 for men and 37 for women.

Recent studies have also shown that the James equation may no longer be accurate once a critical weight is reached (11). This finding led Janmahasatian et al. (12) to develop another formulation for estimating LBM:

| Eq. 3 |

This is an increasing function of weight and plateaus at large values of weight.

Quantitative effects of different LBM formulations on liver SUV for obese patients have not been well studied. From the mathematic formulations of the James and Janmahasatian equations, we should be able to predict their behavior for very obese subjects. The actual data were used to confirm and not establish these mathematic relationships. This was the aim of the present study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Population

More than 1,000 consecutive PET/CT scans over a 5-mo period for patients older than 18 y who underwent recent clinical 18F-FDG PET/CT studies for suspected or known malignancies were considered. Repeated scans for the same patients were discarded. A total of 1,033 studies were retained and included in this study. The study was approved by the ethics committee, and the need to obtain informed consent was waived.

PET Scanning

All patients fasted for at least 4 h before scanning. Patients were scanned either on a Discovery RX with a lutetium yttrium orthosilicate crystal or on a Discovery LS PET/CT scanner with a bismuth germinate crystal (both GE Healthcare) at a target of 60 min after injection of 18F-FDG. Studies on the first system were performed in 3-dimensional acquisition mode with 4.15 min per bed position. The images were reconstructed using ordered-subset expectation maximization algorithms, with matrix, 128 × 128; 21 subsets; 2 iterations; postreconstruction gaussian filter, 3-mm; standard Z filter; pixels, 4.7 mm; and slice thickness, 3.27 mm. The 2-dimensional implementation on the Discovery LS used 2 iterations, 28 subsets, a 5.5-mm postreconstruction gaussian filter, and 3.9-mm pixels. All PET data were reconstructed with and without CT-based attenuation correction.

Determination of SUV, SULJames, and SULJanma

Images were reviewed with Advantage Workstation 4.4 (GE Healthcare) software. Liver mean SUV and SULJames were determined in the nondiseased right hepatic lobe, with a 3-cm-spheric region of interest as a default. SUL values according to the Janmahasatian formulation were derived from

| Eq. 4 |

Data Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD. The relationship between hepatic SULs and patient body morphometrics was assessed by the Pearson coefficient r. The 2-tailed, unpaired t test was used to assess the differences between groups. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. We used MedCalc (version 12.3; MedCalc Software) and SPSS (version 20; SPSS Inc.) for all analyses.

RESULTS

There were 1,033 patients (501 women, 532 men). BW for women was 71.0 ± 20.7 kg (range, 18.0–175.0 kg) and for men 82.9 ± 18.6 kg (range, 23.0–159.0 kg). BMI was 26.6 ± 7.3 (range, 7.0–60.3) and 26.2 ± 5.3 (range, 12.2–51.7) for women and men, respectively. Table 1 summarizes patients’ characteristics.

TABLE 1.

Study Patient Characteristics and Comparison of Mean Liver SUL in Women and Men According to James and Janmahasatian (Janma) Formulations

| Characteristic | Women (n = 501) | Men (n = 532) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 56.8 ± 15.4 | 58.3 ± 15.1 | 0.1 |

| Height (cm) | 163.2 ± 7.3 | 177.5 ± 8.8 | <0.0001 |

| Weight (kg) | 71.0 ± 20.7 | 82.9 ± 18.6 | <0.0001 |

| BMI | 26.6 ± 7.3 | 26.2 ± 5.3 | 0.3 |

| LBMJames | 45.8 ± 6.0 | 62.2 ± 9.0 | <0.0001 |

| LBMJanma | 42.3 ± 7.3 | 61.7 ± 8.9 | <0.0001 |

| SUV | 2.14 ± 0.43 | 2.09 ± 0.40 | 0.09 |

| SULJames | 1.42 ± 0.25 | 1.58 ± 0.26 | <0.0001 |

| SULJanma | 1.30 ± 0.21 | 1.57 ± 0.25 | <0.0001 |

There was no statistically significant difference between liver SUV in women (2.14 ± 0.43) and men (2.09 ± 0.40) (P = 0.09). However, female patients had a lower hepatic SULJames (1.42 ± 0.25) than male patients (1.58 ± 0.26) (P < 0.0001). Liver SULJanma was also lower in women (1.30 ± 0.21) than in men (1.57 ± 0.25) (P < 0.0001; Table 1). There was no statically significant difference in liver SUV or SUL using either formulation with one or the other scanner, with P values varying between 0.1 and 0.5.

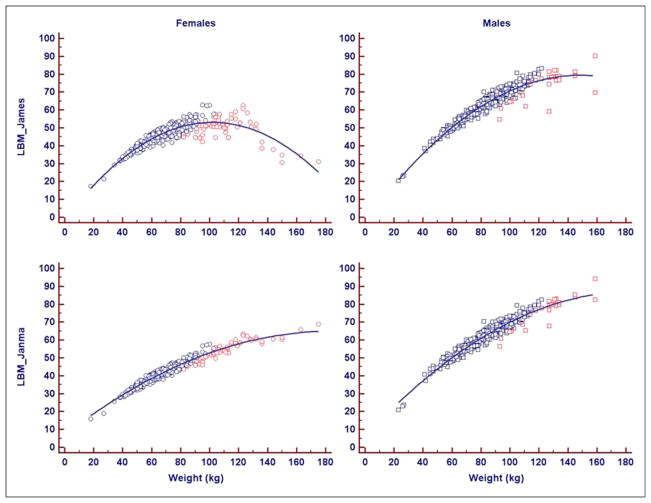

Figure 1 is a graph showing the dependence of LBM on BW. A distribution around an inverted parabola is seen for LBMJames, more pronounced for women as the extremum is reached, with the LBM decreasing for very obese women.

FIGURE 1.

Graph showing dependence of LBM on BW. Distribution around inverted parabola is seen for LBMJames, more pronounced for women as extremum is reached, with LBMJames decreasing for obese women. This does not occur with Janmahasatian formulation of LBM. Blue = BMI < 35; red = BMI ≥ 35.

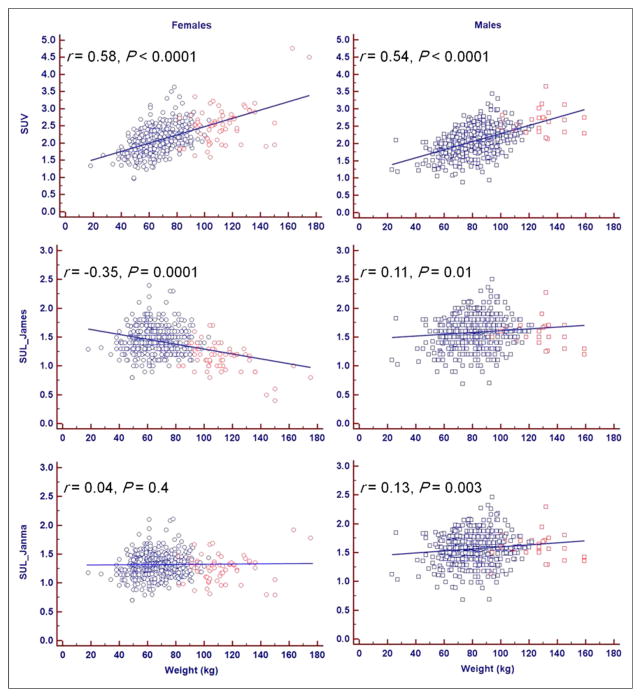

SUV has a significantly moderate positive correlation with weight for both women (r = 0.58, P < 0.0001) and men (r = 0.54, P < 0.0001). This correlation is reduced in men (r = 0.11, P = 0.01) and becomes negative for women (r = −0.35, P = 0.0001) with the James formulation of SUL. The Janmahasatian formulation annuls the correlation between SUL and weight for women (r = 0.04, P = 0.4) and decreases it for men (r = 0.13, P = 0.003). This information is summarized in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

SUV and SUL vs. weight. SUV has significant moderate positive correlation with weight for both women and men. This correlation is reduced in men and becomes negative for women with James formulation of SUL. Janmahasatian formulation annuls correlation between SUL and weight for women and decreases it for men. Blue = BMI < 35; red = BMI ≥ 35.

The plot of hepatic SULJames to BW of women suggested the heavier subjects drive the negative correlation for SULJames. A subgroup analysis of obese women (BMI ≥ 35, n = 61) showed a significantly lower mean hepatic SULJames (1.14 ± 0.25) than the other women (BMI < 35, n = 440, SULJames = 1.46 ± 0.23) (P < 0.0001). There was no statistically significant difference in SUL according to the Janmahasatian formulation between these 2 groups (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Subgroup Comparison of SUV and SUL of Obese Patients (BMI ≥ 35) of Either Sex to Their Leaner Counterparts (BMI < 35)

| Subgroup | BMI < 35 (n = 440 women, 503 men) | BMI ≥ 35 (n = 61 women, 29 men) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| SUV | |||

| Women | 2.08 ± 0.37 | 2.56 ± 0.57 | <0.0001 |

| Men | 2.06 ± 0.38 | 2.61 ± 0.36 | <0.0001 |

| SULJames | |||

| Women | 1.46 ± 0.23 | 1.14 ± 0.25 | <0.0001 |

| Men | 1.59 ± 0.26 | 1.54 ± 0.24 | 0.3 |

| SULJanma | |||

| Women | 1.30 ± 0.20 | 1.25 ± 0.24 | 0.09 |

| Men | 1.57 ± 0.25 | 1.59 ± 0.22 | 0.7 |

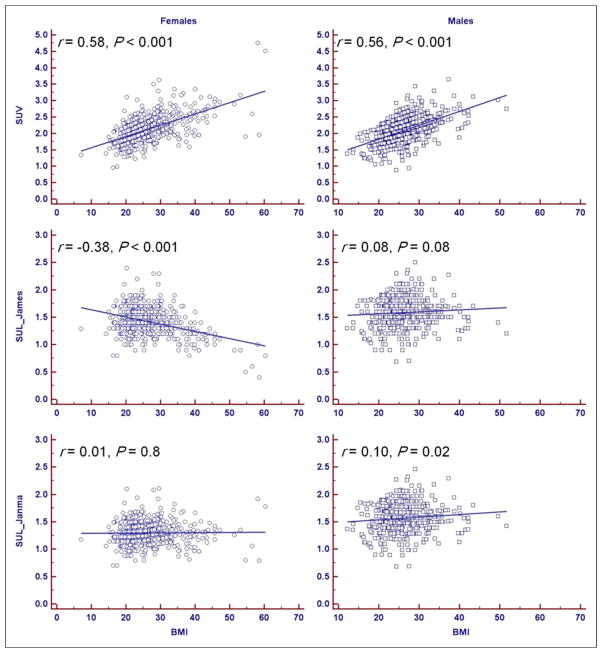

SUV has a significant moderate positive correlation with BMI for both women (r = 0.58, P < 0.001) and men (r = 0.56, P < 0.001). This correlation is lost in men (r = 0.08, P = 0.08) and becomes negative for women (r = −0.38, P < 0.001) with the James formulation of SUL. The Janmahasatian formulation annuls the correlation between SUL and BMI for women (r = 0.01, P = 0.8) and reduces it for men (r = 0.10, P = 0.02) (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

SUV and SUL vs. BMI. SUV has significant moderate positive correlation with BMI for both women and men. This correlation is lost in men and becomes negative for women with James formulation of SUL. Janmahasatian formulation annuls correlation between SUL and BMI for women and decreases it for men.

The negative correlation of SULJames in the female patients was reduced to non-significance when the very obese women (BMI ≥ 35) were excluded from the analysis (BW, r = 0.13, P = 0.8; BMI, r = −0.03, P = 0.5).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that the application of LBM correction of SUV in female patients according to the James formulation resulted in a significant negative correlation of hepatic SUL to total BW (r = −0.35, P < 0.0001) and BMI (r = −0.38, P < 0.001). This finding is seemingly contrary to previous publications that suggested LBM correction prevented a falsely elevated SUV in obese patients because 18F-FDG did not significantly accumulate in white fat (5). These very low SUL values are driven by the markedly lower liver SUL in very obese women.

The James equation for LBM is commonly incorporated into modern PET/CT systems and viewing workstations (10). When the LBM derived from this equation is graphed against BW, an inverted parabolic function is created (13). Therefore, the LBM values start to decrease after a critical weight, leading to what is likely an underestimation of LBM and an undercorrection of SUV in obese patients (11). This may explain the seemingly paradoxically low hepatic SUL in the female patients in this study.

Janmahasatian et al. (12) derived equations yielding the adjusted fat free mass that is almost equal to LBM for a wide range of BW. The SUV corrected with the Janmahasatian formulation does prevent very low SUL in obese patients and should be considered. Alternatively, direct measurement of body fat content by CT could also be considered.

We acknowledge some limitations of our study. Although we started with a large number of PET/CT studies (1,033), the number of obese women (BMI ≥ 35) included was not very large (61), though large enough to elucidate the behavior of LBM as given by the James formulation at high weights. The calculated critical value of BMI for female patients is 37, close enough to our chosen cutoff value. The study included too small a number of very obese men with a BMI ≥ 43 (only 4). This is the predicted BMI value beyond which we should see declining values for LBM as given by the James formulation for male patients.

CONCLUSION

Quantitative measurement of 18F-FDG PET scans is important in determining the outcome of patients with cancer. SUV is the predominant quantitative clinical index. However, absolute SUV does not accurately reflect tumor metabolism because white adipose tissue accumulates less 18F-FDG than other normal tissues in animals. We found inappropriately low hepatic SUL values in the very obese female patients. The same behavior is predicted to happen in morbidly obese male patients, possibly due to the known limitation of LBM equations used in modern PET/CT scanners. Revised LBM equations may be more accurate and these deserve further evaluation. Because obesity is a progressing epidemic, with patients weighing more than ever before, a reassessment of the LBM formulas used in modern PET/CT scanners should be seriously considered, with a strong recommendation to the PET/CT scanner and reading workstation manufacturers to change their software appropriately with the replacement of the James equations for LBM with the Janmahasatian formulae.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Weber WA. Use of PET for monitoring cancer therapy and for predicting outcome. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:983–995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fletcher JW, Djulbegovic B, Soares HP, et al. Recommendations on the use of 18F-FDG PET in oncology. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:480–508. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.047787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warburg OH, Dickens F. Metabolism of Tumours. New York, NY: Richard R. Smith, Inc; 1931. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Som P, Atkins H, Bandoypadhyay D, et al. A fluorinated glucose analog, 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (F-18): nontoxic tracer for rapid tumor detection. J Nucl Med. 1980;21:670–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zasadny KR, Wahl RL. Standardized uptake values of normal tissues at PET with 2-[fluorine-18]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose: variations with body weight and a method for correction. Radiology. 1993;189:847–850. doi: 10.1148/radiology.189.3.8234714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sugawara Y, Zasadny KR, Neuhoff AW, Wahl RL. Reevaluation of the standardized uptake value for FDG: variations with body weight and methods for correction. Radiology. 1999;213:521–525. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.2.r99nv37521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hicks RJ. The role of PET in monitoring therapy. Cancer Imaging. 2005;5:51–57. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2005.0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wahl RL, Jacene H, Kasamon Y, Lodge MA. From RECIST to PERCIST: evolving considerations for PET response criteria in solid tumors. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(suppl 1):122S–150S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paquet N, Albert A, Foidart J, Hustinx R. Within-patient variability of 18F-FDG: standardized uptake values in normal tissues. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:784–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.James W, Waterlow J. Research on Obesity: A Report of the DHSS/MRC Group. London, England: H.M.S.O; 1976. U.K. Department of Health and Social Security/Medical Research Council Group on Obesity Research. [Google Scholar]

- 11.La Colla L, Albertin A, La Colla G. Pharmacokinetic model-driven remifentanil administration in the morbidly obese. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2009;48:397–398. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200948060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janmahasatian S, Duffull SB, Ash S, Ward LC, Byrne NM, Green B. Quantification of lean bodyweight. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44:1051–1065. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544100-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.La Colla L, Albertin A, La Colla G, et al. Predictive performance of the ‘Minto’ remifentanil pharmacokinetic parameter set in morbidly obese patients ensuing from a new method for calculating lean body mass. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49:131–139. doi: 10.2165/11317690-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]