Abstract

We report the use of second-harmonic generation (SHG) microscopy in conjunction with circular dichroism (CD) to differentiate normal skin from that in the connective tissue disorder osteogenesis imperfecta (OI). Osteogenesis imperfecta results from mutations in the collagen triple helix, where the individual chains are defective, leading to abnormal folding, and ultimately, abnormal fibril/fiber organization. Second-harmonic-generation circular dichroism successfully differentiated normal human and OI skin tissues, whereas other SHG polarization schemes did not provide discrimination, suggesting this approach has high sensitivity for studying the difference in chirality in the mutated collagen. We further suggest that the method has clinical diagnostic value, as it could be performed with minimal invasion.

Second harmonic generation (SHG) microscopy has emerged as a powerful tool to visualize the supramolecular assembly of collagen in a variety of tissues [1]. Much of this effort has been directed at providing quantitative metrics to differentiate normal from diseased tissues in a wide range of pathologies [2–4]. Concurrently, significant effort has been directed at understanding the polarization signatures of the SHG process, both in terms of the excitation and emission characteristics. For example, these can be used to determine the helical pitch angle [5] and fiber alignment, respectively [6,7]. However, to date, these metrics have had little direct impact on differentiating normal and diseased tissues. Here we describe a new polarization implementation by combining SHG with circular dichroism (CD) for probing tissue structure and demonstrate the process on the human connective tissue disorder osteogenesis imperfecta (OI).

OI is a heritable human disease characterized by recurrent bone fractures, stunted growth, defective teeth, and other symptoms from abnormal tissues comprised of type I collagen. OI results from mutations within the Col1A1 or Col1A2 genes that affect the primary structure of the collagen chain that induces changes in the secondary structure of the collagen trimers, which incorporate the mutant chains. The ultimate outcome is collagen fibrils that are either abnormally organized, small, or both, resulting in defects at the anatomic level.

We previously used SHG to delineate normal and diseased tissues in the osteogenesis imperfecta mouse model (OIM) for OI using several different signatures, including SHG creation attributes, morphology, and SHG intensity [4,8]. Most importantly, much of this analysis was performed in skin, which displays little clinical presentation, but is of significant clinical diagnostic value. However, the genotype in the OIM model [9] is different from that of the human disease. In the former, the collagen exists as an α1 homotrimer, whereas in normal tissues the triple helix has 2α1α2 chain incorporation. In human OI, the helix has this incorporation but displays either mis-sense or non-sense mutations. These defects change the supramolecular structure that, in principle, could be detected through the use of SHG polarization analysis.

To address this potential, we use the combination of SHG with CD to probe changes in the collagen triple helix in normal and OI human skin tissues. Conventional CD using linear optics results from differential absorption between right and left handed circularly polarized (CP) light due to the chirality intrinsic to every protein helix. Specifically, a properly folded protein will have a non-vanishing CD, whereas this will go to zero for a completely unfolded or denatured protein. Circular dichroism has been coupled with SHG to study the chirality of interfaces. Conventional linear CD is a very small effect, ~0.1%, however the pioneering work of Hicks [10] showed that nearly 100% modulation could be achieved when implemented into surface SHG in a reflection geometry. Here, the effect arises in part due to the coherence of the SHG, rather than linear absorption [11]. These theoretical and experimental efforts have been developed for surface SHG-CD, and to the best of our knowledge have not been demonstrated for SHG of tissues in a high-resolution transmission geometry.

The SHG microscope has been presented in detail previously [12]. Briefly, the system is built around a Olympus Fluoview 300 laser scanning microscope with excitation at 890 nm provided by a Coherent Mira ti:sapphire oscillator. The SHG is collected in the forward direction with a 0.8 and 0.9 NA lenses for excitation and collection, respectively. The SHG is isolated through a 445 nm band-pass filter and detected with a single photon counting Hammamatsu 7421 GaAsP photomultiplier.

We use a combination of two waveplates to achieve circular polarization at the microscope focus. A zero order λ/4 plate first converts the linear polarization of the laser to that of a circular one. However, due to non-45° reflections in the scanning system, and birefringence and strain in dichroics and other optics, the resulting polarization at the focus will become elliptical. To compensate for this scrambling, a λ/2 plate is placed before the λ/4 plate that functions as a variable retarder by introducing a fixed ellipticity in the opposite direction. This intentional polarization distortion is then corrected upon traversing the optical path of the microscope, resulting in the desired circular polarization at the focus. This condition is found by imaging a specimen with cylindrical symmetry and achieving a “ring stain”, where here we used giant unilamellar vesicles stained with the voltage sensitive dye Di-8-ANEPPS. A liquid crystal (LC) phase retarder (Meadowlark Optics) was added right after the quarter waveplate to change the right handed circular polarization (RHCP) to left handed circular polarization (LHCP).

Normalized SHG-CD is defined as |IRHCP − ILHCP|/((IRHCP + ILHCP)/2), where IRHCP and ILHCP are the integrated intensity of the SHG images for RHCP and LHCP excitation, respectively. As the sign of the CD response will depend on fiber orientation, we take the absolute value and normalize it to the average intensity to determine the magnitude of the difference in the RHCP and LHCP response.

Human OI and control skin tissues were acquired at the Hospital for Special Surgery (New York, NY) under an approved internal review board (IRB) protocol. In this data, there were 3 OI and 4 normal tissues, where each was approximately 30 µm in thickness, and 8–10 fields of view were acquired per specimen, from approximately the middle of the sections. Student’s t-test was used for statistical comparison of the normal and OI tissues. Mouse tendon was used as a control to establish the SHG-CD response in tissue.

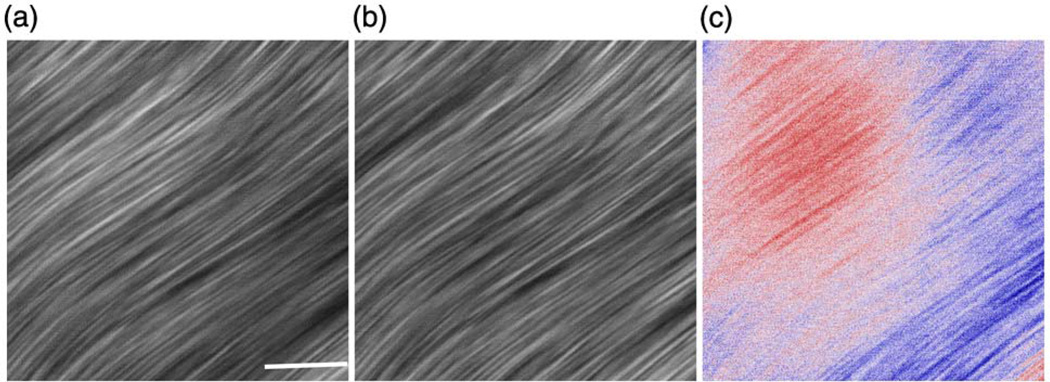

While SHG-CD on surfaces has been documented, the magnitude of the effect in tissues has not been established. Here, we used mouse tendon to determine the SHG-CD response in a well-ordered, highly aligned normal tissue. One limitation of SHG polarization methods is that the effects can become scrambled due to scattering within 1–2 scattering lengths or ~50 µm for skin [13]. This was not limiting for the skin specimens used here but is a confounding factor for whole mouse tendons. Instead, we cleared the tendon in 50% glycerol, which essentially eliminates scattering [14] and this approach has previously shown the ability to retain the polarization signatures [14]. Representative images of the RHCP, LHCP, and difference (CD) images are shown in Fig. 1.While the images are similar in terms of overall morphology, the intensities are quantitatively distinct, where positive and negative differences are given in blue and red, respectively. Integration and normalization to the average intensities showed a difference of 5% for the CD response. For comparison, Schanne-Klein et al. [15] used SHG-CD on collagen thin films in a surface reflection geometry and found a response of ~20%.

Fig. 1.

(Color online) Representative SHG images for mouse tendon, where (a), (b), and (c) are the RHCP, LHCP, and difference (CD) images, respectively. Positive and negative differences in (c) are given in blue and red, respectively. Scale bar = 25 µm.

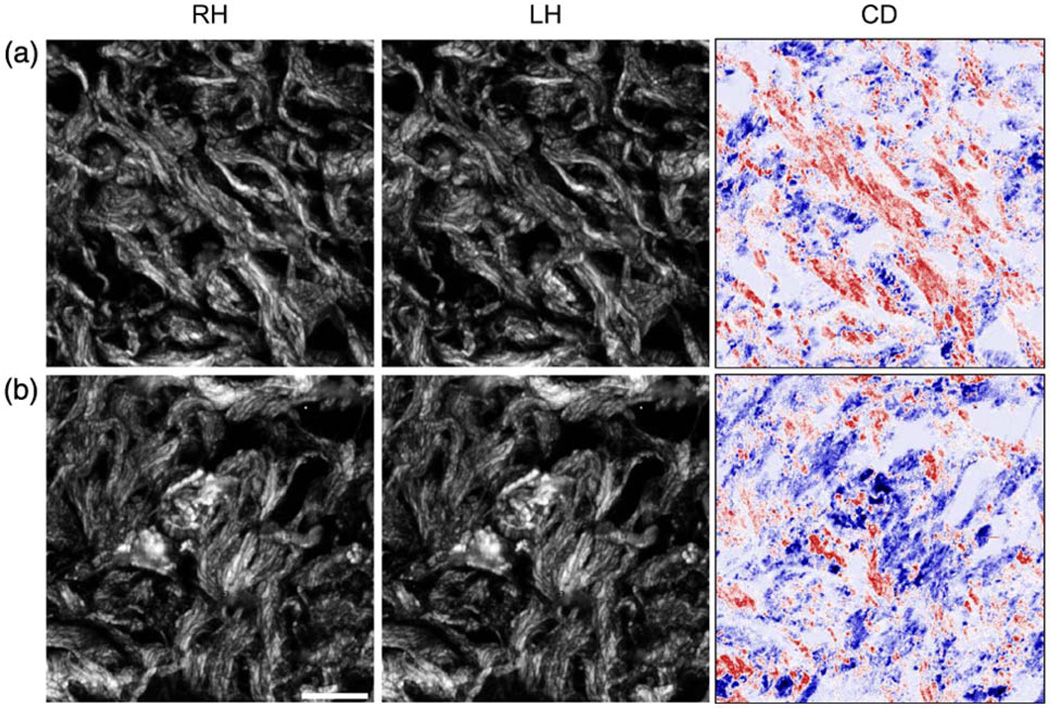

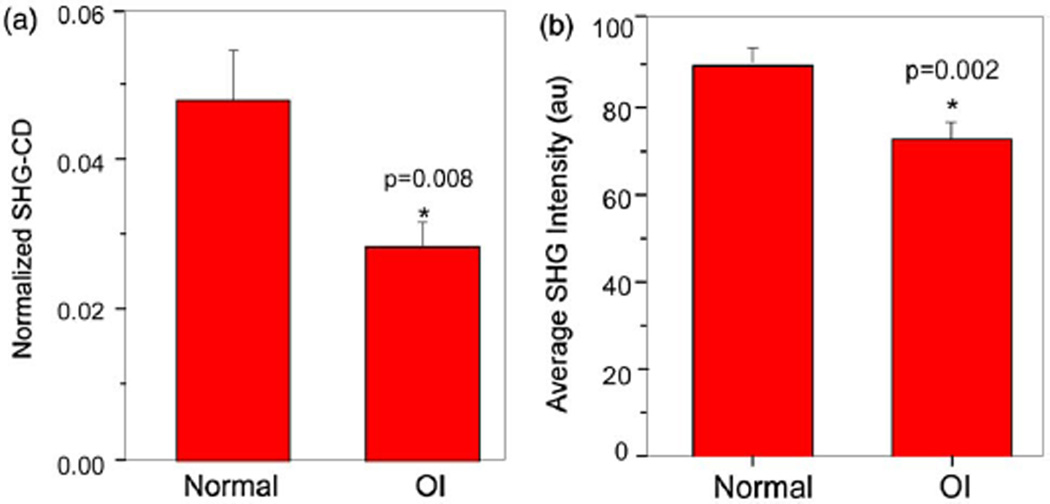

Representative SHG-CD data for normal (a) and OI (b) tissues are shown in Fig. 2, giving the RHCP, LHCP, and difference (CD) images. Similar to the tendon, large differences are not readily apparent by inspection, but are revealed by image subtraction and normalization. Figure 3(a) shows the bar graph of the normalized CD response for these tissues. We found the CD magnitude to be approximately 4.8% and 2.8% for the normal and OI, respectively, where these are statistically different (p = 0.008).

Fig. 2.

(Color online) Representative SHG images for (a) normal and (b) OI skin tissues, showing RHCP, LHCP, and difference (CD) images, respectively, where positive and negative differences are given in blue and red, respectively. Scale bar = 25 µm.

Fig. 3.

(Color online) (a) Normalized SHG-CD response and (b) average SHG intensity, where n = 3 for OI and n = 4 for normal tissues.

This difference is also consistent with the change in helical structure in the OI tissues. The collagen OI helix is mis-folded relative to normal collagen due to either mutations at glycine sites that determine the secondary structure (mis-sense) or abnormally short chain lengths (non-sense). The extreme limit of a completely mis-folded protein would have a vanishing CD response, thus the OI tissue in principle should have a lower SHG-CD response than normal tissue. We note that measuring the SHG angular intensity, i.e., intensity as a function of linear excitation angle, which probes the individual α-chain pitch angle, did not show consistent differences on these same tissues. In contrast the SHG-CD should be sensitive to the chirality of the triple helix, which is not the sum of the individual chains, and in fact has the opposite handedness. Second harmonic generation signal anisotropy also failed to yield discrimination.

We can also compare the average SHG intensities in the human skin images. The SHG intensity is a convolved metric arising from the square of the collagen concentration and organization. The resulting data is shown in the bar graph in Fig. 3(b), which is an average over all the tissues in the normal and OI specimens. The average SHG intensity from the OI tissues was about 20% lower than the normal, where this difference is statistically different (p = 0.002). We note that the OI tissues were of different types of the disease, meaning the form of the mutation could result in changes in the collagen concentration or organization or both. In either case the SHG in the OI tissues should be lower in intensity relative to the normal tissues.

It is interesting to question the mechanism of the SHG-CD response measured here. Linear CD is an absorptive effect, where the difference is due to chirality and ascribed to the magnetic dipole interaction. However, the SHG response is nonlinear, coherent, and does not necessarily require absorption. On surfaces, SHG-CD has been ascribed to either electric dipole interactions, arising from two distinct dipoles (local) or a magnetic dipole interaction (nonlocal) or a combination there of [11]. The former is more readily ascribed to the excitation being on or near resonance and the latter has been observed in helical polymers. Recently, Barzda [16] showed that there were two distinct dipole moments in the collagen structure, suggesting a local interpretation. On the other hand the 890 nm excitation wavelength is somewhat removed from the nearest 2-photon resonance of cross linked collagen (~720 nm), which is more consistent with a nonlocal origin, especially when coupled with the helical nature of the protein helix. In sum, these observations suggest that the observed SHG-CD probably cannot be ascribed to either origin uniquely but is probably a combination of both local and nonlocal contributions.

While the mechanism of SHG-CD in tissues requires further study, the present work shows that this new imaging contrast mechanism can discriminate normal and OI human skin tissues. This is significant as it may become a diagnostic tool. For example, the conventional OI diagnosis involves a painful bone biopsy whereas the SHG-CD approach can be performed in a skin biopsy or even the reflection SHG geometry in vivo. There are currently both stem cell and gene therapy approaches under trial for OI, and this approach could aid in the diagnosis and determination of treatment efficacy. These are important considerations as there remains a strong disconnection between the level of genetic defect and observed symptoms.

Acknowledgments

P. J. Campagnola gratefully acknowledges support under National Institutes of Health (NIH) CA136590.

References

- 1.Campagnola PJ. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:3224. doi: 10.1021/ac1032325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conklin MW, Eickhoff JC, Riching KM, Pehlke CA, Eliceiri KW, Provenzano PP, Friedl A, Keely PJ. Am. J. Pathol. 2011;178:1221. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strupler M, Pena AM, Hernest M, Tharaux PL, Martin JL, Beaurepaire E, Schanne-Klein MC. Opt. Express. 2007;15:4054. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.004054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lacomb R, Nadiarnykh O, Campagnola PJ. J. Biophys. 2008;94:4504. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.114405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plotnikov SV, Millard AC, Campagnola PJ, Mohler WA. J. Biophys. 2006;90:693. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.071555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stoller P, Reiser KM, Celliers PM, Rubinchik AM. J. Biophys. 2002;82:3330. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75673-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfeffer CP, Olsen BR, Legare F. Opt. Express. 2007;15:7296. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.007296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nadiarnykh O, Plotnikov S, Mohler WA, Kalajzic I, Redford-Badwal D, Campagnola PJ. J. Biomed. Opt. 2007;12:051805. doi: 10.1117/1.2799538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chipman SD, Sweet HO, McBride DJ, Jr, Davisson MT, Marks SC, Jr, Shuldiner AR, Wenstrup RJ, Rowe DW, Shapiro JR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:1701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hicks JM, Petralli-Mallow T. Appl. Phys. B. 1999;68:589. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hache F, Mesnil H, Schanne-Klein MC. J. Chem. Phys. 2001;115:6707. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen X, Nadiarynkh O, Plotnikov S, Campagnola PJ. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:654. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nadiarnykh O, Campagnola PJ. Opt. Express. 2009;17:5794. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.005794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaComb R, Nadiarnykh O, Carey S, Campagnola PJ. J. Biomed. Opt. 2008;13:021109. doi: 10.1117/1.2907207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pena AM, Boulesteix T, Dartigalongue T, Schanne-Klein MC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10314. doi: 10.1021/ja0520969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tuer AE, Krouglov S, Prent N, Cisek R, Sandkuijl D, Yasufuku K, Wilson BC, Barzda V. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:12759. doi: 10.1021/jp206308k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]