Abstract

Objective

In mast cell (MC) neoplasms, clinical problems requiring therapy include i) the local aggressive and sometimes devastating growth of MC and ii) mediator-related symptoms. A key mediator of MC responsible for clinical symptoms is histamine. Therefore, the use of histamine receptor (HR) antagonists is an established approach to block histamine effects in these patients.

Methods and Results

We screened for additional beneficial effects of HR antagonists and asked whether any of these agents would also exert growth-inhibitory effects on primary neoplastic MC, the human MC line HMC-1, and on two canine MC lines, C2 and NI-1. We found that the HR1 antagonists terfenadine and loratadine suppress spontaneous growth of HMC-1, C2, and NI-1 cells, as well as growth of primary neoplastic MC in all donors tested (human patients, n=5; canine patients, n=8). The effects of both drugs were found to be dose-dependent (IC50: terfenadine, 1-20 μM; loratadine, 10-50 μM). Both agents also produced apoptosis in neoplastic MC and augmented apoptosis-inducing effects of two KIT-targeting drugs, PKC412 and dasatinib. The other HR1 antagonists (fexofenadine, diphenhydramine) and HR2 antagonists (famotidine, cimetidine, ranitidine) tested did not exert substantial growth-inhibitory effects on neoplastic MC. None of the histamine receptor blockers were found to modulate cell cycle progression in neoplastic MC.

Conclusions

The HR1 antagonists terfenadine and loratadine, in addition to their anti-mediator activity, exert in vitro growth-inhibitory effects on neoplastic MC. Whether these drugs (terfenadine) alone or in combination with KIT-inhibitors, can also affect in vivo neoplastic MC growth remains to be determined.

Keywords: mastocytosis, mastocytoma, histamine, terfenadine, loratadine

Introduction

Systemic mast cell (MC) disorders, also referred to as systemic mastocytosis (SM), are hematologic neoplasms characterized by prolonged survival and accumulation of neoplastic MC in one or more visceral organs [1-5]. Clinical symptoms result from effects of MC-derived mediators and/or from the local accumulation and sometimes destructive growth of MC in various organs [1-5]. Mediator-related symptoms may be mild, but may also be severe or even life-threatening [3-5]. From a clinical point of view, a most relevant MC-derived mediator is histamine. Therefore, histamine receptor (HR) blockers, often in form of a combination of HR1 and HR2 antagonists, are prescribed in these patients [2-5]. Using these drugs mediator-related symptoms can be kept under control in most patients.

Both indolent and aggressive variants of SM have been reported [1-7]. The WHO classification defines cutaneous mastocytosis, indolent SM (ISM), SM with associated clonal hematologic non-MC disease (SM-AHNMD), aggressive SM (ASM), and MC leukemia (MCL) [7]. In ASM and MCL, the aggressive and sometimes devastating growth of MC in various organs is a typical finding [6,7]. A number of different cytoreductive agents have been proposed for these patients, such as interferon-alpha, cladribine (2CdA), and novel tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as midostaurin (PKC412) or dasatinib [8-18]. It has also been described that combinations of anti-neoplastic drugs sometimes produce cooperative or even synergistic growth-inhibitory effects in vitro on neoplastic MC [14-16]. In most patients with advanced SM, however, the disease is resistant to conventional drugs and the prognosis is grave [6,7].

Several previous and more recent data suggest that histamine receptor antagonists may exert growth-inhibitory effects on neoplastic cells [19-22]. We have recently shown that the HR1 antagonists terfenadine and loratadine inhibit the growth of neoplastic basophils in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) [22]. However, the effects of HR antagonists on growth of neoplastic MC has not been examined so far. The aims of the present study were to evaluate growth-inhibitory effects of HR1- and HR2 antagonists on neoplastic MC.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

The HR1 antagonists terfenadine, loratadine, and fexofenadine, the HR2 antagonists ranitidine, famotidine, and cimetidine, the HR3 antagonist thioperamide, the HR4 antagonist JNJ7777120, the HR2 agonist amthamine, and histamine were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The HR1 blocker diphenhydramine was purchased from Bejing Taiyang Pharmaceutical Industry (Bejing, PR China). The KIT-targeting multikinase inhibitor PKC412 (midostaurin) was kindly provided by Dr. Paul Manley (Novartis Oncology, Basel, Switzerland). Dasatinib was kindly provided by Dr. Francis Lee (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ, USA). Stock solutions of diphenhydramine and ranitidine were prepared by dissolving in distilled water. Stock solutions of other HR antagonists, PKC412, and dasatinib were prepared by dissolving in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). RPMI 1640 medium and fetal calf serum (FCS) were from PAA Laboratories (Pasching, Austria), Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM) from Gibco Life Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD), and 3H-thymidine from Amersham (Buckinghamshire, UK).

Culture of cell lines and isolation of primary MC

The human MC leukemia cell line HMC-1 [23] was kindly provided by Dr. Joseph H. Butterfield (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). Two subclones were used, namely HMC-1.1 harboring KIT V560G but not KIT D816V, and HMC-1.2 harboring KIT V560G as well as KIT D816V [24]. The canine mastocytoma cell line C2 [25] was kindly provided by Dr. Warren Gold (Cardiovascular Research Institute, University of California, San Francisco, CA). C2 cells and HMC-1 cells were cultured in IMDM supplemented with 10% FCS and antibiotics at 5% CO2 and 37°C. Cells were passaged every 3-5 days and re-thawed from an original stock every 6-8 weeks.

Human primary neoplastic cells were obtained by bone marrow (BM) aspiration (diagnostic samples) in 5 patients with SM (ISM, n=3; ASM, n=1; SM with associated hematologic neoplasm, SM-AHNMD, n=1; Table 1) after informed consent was given. BM mononuclear cells (MNC) were isolated by centrifugation using Ficoll. Isolated cells were recovered and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FCS and antibiotics at 5% CO2 and 37°C. In control experiments, MNC from normal BM (n=3), normal peripheral blood (PB) MNC (n=3 donors), and normal MC cultured from CD133+ cord blood progenitor cells as described [26], were examined.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

| Human Patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Age | Sex | Diagnosis | KIT mutation status | Serum Tryptase (μg/l) |

| 1 | 53 | m | SM-AHNMD (ISM-SLL) | D816V pos | 163 |

| 2 | 75 | m | ASM | D816V pos | 1432 |

| 3 | 75 | m | ISM | D816V neg | 17.6 |

| 4 | 66 | m | ISM | D816V pos | 49.9 |

| 5 | 53 | w | ISM | D816V pos | 12.5 |

| Canine Patients | |||||

| # | Age | Sex | Diagnosis (Grade) | KIT mutation status | Breed |

|

| |||||

| 6 | 6 | m | MCT (II) | n.d. | Retriever |

| 7 | 6 | f/s | MCT (I) | n.d. | American Staffordshire Terrier |

| 8 | 9 | f | MCT (III) | n.d. | Bernese Mountain Dog |

| 9 | 11 | m/n | MCT (III) | *SNP exon 11 (C/T) | Crossbreed |

| 10 | 12 | f/s | MCT (III) | *SNP exon 11 (C/T) | Bullmastiff |

| 11 | 13 | f | MCT (II) | exon 11 neg | Boxer |

| 12 | 8 | f/s | MCT (II) | exon 11 neg | Bernese Mountain Dog |

| 13 | 3 | m | Malignant Mastocytosis | exon 8 | Crossbreed |

| Feline Patients | |||||

| # | Age | Sex | Diagnosis | KIT mutation status | Breed |

|

| |||||

| 14 | 10 | f/s | SM | ITD exon 8 | European shorthair |

| 15 | 19 | m/n | SM | ITD exon 8 | European shorthair |

SM-AHNMD, systemic mastocytosis associated with a clonal hematological non-mast-cell lineage disease; ISM, indolent systemic mastocytosis; SLL, small lymphocytic lymphoma; ASM, aggressive systemic mastocytosis; MCT, mast cell tumor; n.d., not done; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; ITD, internal tandem duplication.

C/T SNP in KIT exon 11 at amino acid position 581.

In 8 canine patients (histologic grade I: n=1; grade II: n=3; grade III: n=3; malignant mastocytosis/MCL, n=1) and in 2 feline patients with systemic mastocytosis, primary MC were isolated from surgical specimens (Table 1). MC were isolated using collagenase type II (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ) as reported [27,28]. Isolated cells were examined for the percentage of MC by Wright Giemsa staining, and cell viability by Trypan blue exclusion. In the canine patient with malignant mastocytosis/MCL, neoplastic MC from PB were passaged serially and cloned by limiting dilution. One clone, designated NI-1 was used in the present study (Table 1). NI-1 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium and 10% FCS. This clone was found to harbour several homozygous KIT mutations, including two missense mutations at nucleotides 107 (C to T) and 1187 (A to G), a 12 bp duplication mutation at nucleotide 1263 of KIT (repeat of AATCCTGACTCA), and a 12 bp deletion at nucleotide 1550 (deleted sequence: GTAACAGCAAG).

Treatment of cells with HR agonists and HR antagonists and measurement of 3H-thymidine uptake

Primary neoplastic MC (human, canine, feline) and cell lines were cultured in medium plus 10% FCS in the presence or absence of various concentrations of amthamine (0.1-50 μM), histamine (0.1-50 μM), or HR antagonists (0.01-50 μM) at 37°C for 48 hours. In time course experiments, HMC-1 cells (both subclones), C2 cells, and NI-1 cells were incubated with terfenadine and loratadine (10 μM) for various time periods (6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours). In select experiments, combinations of HR1 antagonists (terfenadine, loratadine) and PKC412 or dasatinib (at fixed ratio of drug-concentrations) were applied. After incubation, 0.5 μCi 3H-thymidine was added (37°C, 16 hours). Cells were then harvested on filter membranes (Packard Bioscience, Meriden, CT) in a Filtermate 196 harvester (Packard Bioscience). Filters were air-dried, and the bound radioactivity was counted in a β-counter (Top-Count NXT, Packard Bioscience). All experiments were performed in triplicates.

Evaluation of apoptosis by morphology, Tunel assay, and Annexin V staining

The effects of HR1 and HR2 antagonists on apoptosis in C2 cells, NI cells, and HMC-1 cells were analyzed by morphologic examination and by Tunel assay. Cells were incubated with various concentrations of amthamine (100 μM), histamine (100 μM), HR antagonists (up to 100 μM), or control medium at 37°C for 24 or 48 hours. In a separate set of experiments, PKC412 and dasatinib alone or in combination with terfenadine or loratadine (in suboptimal concentrations) were applied. In control experiments, normal BM MNC, PB MNC, or cultured MC were incubated with control medium, terfenadine (up to 15 μM), or loratadine (up to 75 μM) for 24 or 48 hours at 37°C. After incubation with histamine, amthamine, or HR blockers, the percentage of apoptotic cells [29] was quantified by microscopy on Wright-Giemsa-stained slides. To confirm apoptosis, a Tunel assay was performed using the ‘In situ cell death detection kit-fluorescein’ (Roche) following the manufacturer’s instructions. For flow cytometric determination of apoptosis and viability, combined AnnexinV/propidium iodide staining was performed. HMC-1 cells were exposed to PKC412 (1 μM), terfenadine (2-15 μM), loratadine (10-100 μM), or control medium at 37°C for 24 hours. Thereafter, cells were washed and incubated with AnnexinV-FITC (Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA) in binding-buffer containing HEPES (10 mM, pH 7.4), NaCl (140 mM), and CaCl2 (2.5 mM). Thereafter, propidium iodide (1 μg/ml) was added. Cells were then washed and analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson).

Flow cytometric evaluation of expression of KIT, activated caspase 3, and KIT downstream signaling molecules

Flow cytometry experiments were performed using PE-labeled monoclonal antibodies (mAb) against KIT (104D2) and active caspase 3 (C92-605), the PE-conjugated mAb M89-61 against pAkt, and the Alexa Fluor 647-labeled mAbs N7-548 against rpS6 and clone 47 against pSTAT5. All antibodies were purchased from Becton Dickinson Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ). Before being stained, cells were cultured in the presence or absence of terfenadine (5, 10, and 15 μM), loratadine (25, 50, and 75 μM), or PKC412 (1 μM) for 24 hours. Prior to staining for caspase 3 or for signaling molecules, cells were fixed in formaldehyde (2%) and permeabilized using methanol (100%) at −20°C for 30 minutes. Expression of KIT and intracellular antigens was analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Western blot (WB) experiments and immunoprecipitation (IP)

WB experiments were performed essentially as described [14] using HMC-1 cells exposed to control medium, DMSO (vehicle control), terfenadine (10 μM), or loratadine (50 μM) for 24 hours. In brief, cell samples were washed, incubated in RIPA buffer supplemented with proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Mannheim, Germany; 30 minutes, 4°C), and centrifuged. Proteins were separated by 12% SDS polyacrylamid gel electrophoresis and transferred to a PVDF membrane (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). For detection of cleaved caspases, the following antibodies were used: a rabbit mAb against cleaved caspase-8 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), a polyclonal antibody against cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology), and a polyclonal antibody against cleaved caspase-9 (Cell Signaling Technology). To confirm equal loading, an antibody against beta-actin (Sigma) was applied. Antibody-reactivity was made visible by donkey anti-rabbit IgG and Lumingen PS-3 detection reagent (all from GE Healthcare).

Statistical analysis

To determine the significances in differences in apoptosis in cells exposed to control medium or inhibitors, the Student’s t test for dependent samples was applied. Results were considered statistically significant when p was <0.05.

Results

Effects of HR antagonists on growth of HMC-1 cells and C2 cells

Of all HR antagonists tested, the two HR1 blockers terfenadine and loratadine were found to cause substantial growth inhibition in HMC-1 cells, C2 cells, and NI-1 cells (Figure 1A-D, Table 2A). The effects of both drugs were found to be time-dependent and dose-dependent, with varying IC50 values. Maximum growth-inhibitory effects were observed after 48-72 hours. In all four cell lines, terfenadine was the more potent drug (IC50: HMC-1.1: 5-20 μM; HMC-1.2: 1-10 μM; C2: 5-10 μM; NI-1: 1-10 μM) compared to loratadine (IC50 >10 μM) (Figure 1A-D, Table 2A). Interestingly, the effects of both HR1 antagonists were slightly stronger in HMC-1.2 cells carrying KIT D816V than in HMC-1.1 cells lacking KIT D816V (Table 2A). The other HR antagonists tested including thioperamide and the HR4 antagonist JNJ7777120 did not produce growth-inhibitory effects in MC lines (Table 2A). Similarily, no effects of histamine or amthamine on growth of neoplastic MC were found (data not shown).

Figure 1. Growth-inhibitory effects of terfenadine and loratadine on mast cell lines.

Human neoplastic mast cells (A: HMC-1.1 cells; B: HMC-1.2 cells) and canine neoplastic mast cells (C: C2 cells; D: NI-1 cells) were incubated in control medium (Co) or with various concentrations of terfenadine (left panels) or loratadine (right panels) as indicated at 37°C for 48 hours. Thereafter, uptake of 3H-thymidine into mast cell lines was measured. Results show the percentage of 3H-thymidine uptake compared to medium control (Co on x axis = 100%) and represent the mean±S.D. of at least three independent experiments (n = number of experiments).

Table 2A.

Effects of histamine receptor blockers on growth of neoplastic mast cells

| IC50 values (μM) produced by |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terfenadine | Loratadine | Diphenhydramine | Fexofenadine | Ranitidine | Cimetidine | Famotidine | |

| HMC-1.1 | 5 - 20 | 10 - 35 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| HMC-1.2 | 1 - 10 | 10 - 35 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| C2 | 5 - 10 | 10 - 35 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| NI-1 | 1 - 10 | 35 - 50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

Cells were incubated with various concentrations of histamine receptor antagonists at 37°C for 48 hours. Then, 3H-thymidine uptake was measured. Results are shown as IC50 values (in μM) obtained in at least 3 independent experiments.

Effects of HR antagonists on growth of primary human neoplastic MC

In a next step, we asked whether the HR antagonists would also cause growth inhibition in primary human neoplastic MC. In 3H-thymidine uptake experiments terfenadine and loratadine were found to inhibit the growth of primary neoplastic human MC in a dose-dependent manner in all patients tested (Figure 2A). Similar to drug effects in cell lines, terfenadine was found to be the more potent compound compared to loratadine (Figure 2A). In fact, IC50 values obtained with terfenadine were found to range between 1 and 10 μM, whereas IC50 values obtained with loratadine were >10 μM in all patients tested. Table 2B shows a summary of IC50 values obtained with terfenadine and loratadine and primary neoplastic human MC. In normal cultured MC, neither terfenadine (up to 15 μM) nor loratadine (up to 75 μM) induced apoptosis. In normal PB and BM MNC, high concentrations of terfenadine (≥10 μM) and loratadine (≥75 μM) induced some necrosis, whereas at lower concentrations, neither terfenadine nor loratadine induced an increase in apoptotic or necrotic cells compared to medium control after 24 or 48 hours (data not shown).

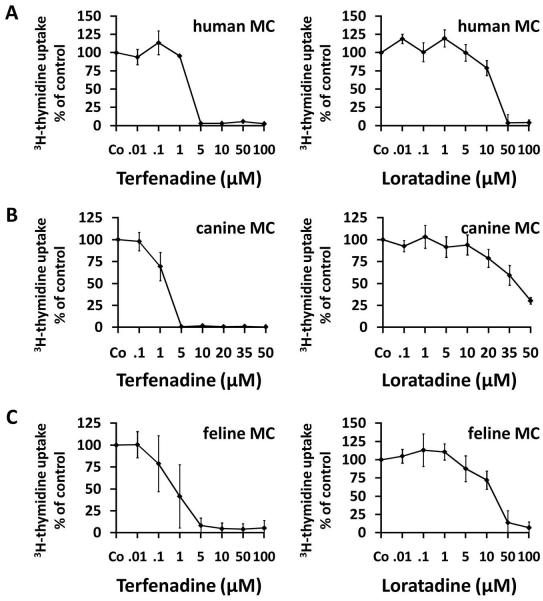

Figure 2. Growth-inhibitory effects of terfenadine and loratadine on primary neoplastic mast cells.

Primary neoplastic bone marrow cells obtained from a human patient with aggressive systemic mastocytosis (A), one canine patient with mastocytoma (B) and one feline patient with mastocytoma (C) were cultured in control medium (Co) or medium containing various concentrations of terfenadine (left panels) or loratadine (right panels) at 37°C for 48 hours. Thereafter, uptake of 3H-thymidine was measured. Results show the percent of 3H-thymidine uptake compared to medium control (Co = 100%) and represent the mean±S.D. of triplicates in each donor.

Table 2B.

Effects of Terfenadine and Loratadine on growth of primary neoplastic mast cells

| IC50 (μM) obtained with |

||

|---|---|---|

| Donor | Terfenadine | Loratadine |

| #1 (human) | 1 - 5 | 10 - 50 |

| #2 (human) | 1 - 5 | 10 - 50 |

| #3 (human) | 1 - 5 | 10 - 50 |

| #4 (human) | 1 -5 10 | - 20 |

| #5 (human) | 1 - 5 | 10 - 20 |

| #6 (dog) | 2.5 - 5 | 10 - 35 |

| #7 (dog) | 2.5 - 5 | 20 - 35 |

| #8 (dog) | 1 - 5 | 10 - 35 |

| #9 (dog) | 0.1 - 1 | 10 - 35 |

| #10 (dog) | 1 - 5 | 1 - 10 |

| #11 (dog) | 1 - 5 | 10 - 20 |

| #12 (dog) | 0.5 - 1 | 5 - 25 |

| #13 (dog) | 1 - 10 | 35 - 50 |

| #14 (cat) | 0.1 - 1 | 1 - 10 |

| #15 (cat) | 1 - 5 | 5 - 50 |

Primary neoplastic mast cells were incubated with various concentrations of terfenadine or loratadine for 48 hours. Then, 3H-thymidine uptake was measured. IC50 values from one experiment are shown.

Effects of HR antagonists on growth of primary canine and feline neoplastic MC

Terfenadine and loratadine were found to inhibit 3H-thymidine uptake and thus growth of primary canine and feline MC in all patients tested (Figure 2B and 2C). The effects of terfenadine and loratadine were dose-dependent (Figure 2B and 2C). Terfenadine was found to be the more potent compound compared to loratadine (Figure 2B and 2C). Table 2B shows a summary of IC50 values obtained with HR antagonists and primary MC in feline and canine patients.

Terfenadine and loratadine induce apoptosis in neoplastic MC

Both terfenadine and loratadine induced dose-dependent apoptosis in HMC-1 cells, C2 cells, and NI-1 cells (Figure 3A). As expected, terfenadine was found to be a more potent compound compared to loratadine (Figure 3A). The apoptosis-inducing effects of both HR1 antagonists could be confirmed by Tunel assay (Figure 3B) and AnnexinV-staining (Figure 4). In addition, we were able to show that terfenadine and loratadine induce caspase 3 activation in HMC-1 cells, C2 cells, and NI-1 cells by flow cytometry (Figure 5A). Moreover, terfenadine and loratadine were found to induce caspase 3 cleavage, caspase 8 cleavage, and caspase 9 cleavage in neoplastic MC in our WB experiments (Figure 5B). The other HR antagonists tested including thioperamide and the HR4 antagonist JNJ7777120 (up to 100 μM) as well as histamine and amthamine did not produce apoptosis in neoplastic MC (data not shown).

Figure 3. Effects of terfenadine and loratadine on survival of neoplastic mast cell.

(A) Neoplastic mast cell lines were incubated in control medium (Co) or in various concentrations of terfenadine (upper panel) or loratadine (lower panel) as indicated at 37°C for 24 or 48 hours. Then, the numbers (percentages) of apoptotic cells were determined by light microscopy. Results show the percentage of apoptotic cells and represent the mean±S.D. of at least 3 independent experiments. In some of the samples, the majority of cells were necrotic cells after 48 hours – these samples were not counted. (B) HMC-1.1 cells, HMC-1.2 cells, C2 cells, and NI-1 cells were cultured in control medium (Co, upper panel), terfenadine (middle panel) or in loratadine (lower panel) at 37°C for 48 hours. Then, apoptosis was examined by a Tunel assay.

Figure 4. Terfenadine- and loratadine-induced apoptosis in HMC-1 cells, C2 cells, and NI-1 cells as determined by AnnexinV-staining and flow cytometry.

Cells were incubated with control medium or in medium containing terfenadine (10 or 15 μM, left panels) or loratadine (50 and 75μM for NI-1 or 75 and 100 μM for HMC-1, C2 and NI-1, right panels) at 37°C for 24 hours. After incubation, cells were stained with propidium iodide and AnnexinV-FITC and were then analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentage of apoptotic cells are depicted for each condition.

Figure 5. Terfenadine and loratadine induce caspase activation in human and canine mast cell lines.

A: HMC-1.1 cells, HMC-1.2 cells, C2 cells, and NI-1 cells were incubated in control medium or in medium containing various concentrations (as indicated) of terfenadine (left panel) or loratadine (right panel) at 37°C for 24 hours. Then, cells were analyzed for expression of active caspase 3 by flow cytometry as described in the text. Results were calculated as percent of positive cells and are expressed as mean±S.D. of at least 3 independent experiments. B: HMC-1.1 cells and HMC-1.2 cells were incubated in control medium, medium containing DMSO (solvent control), 7.5 μM terfenadine or 50 μM loratadine, for 24 hours. Thereafter, cells were analyzed for expression of cleaved caspase 3, cleaved caspase 8, and cleaved caspase 9 by Western blotting as described in the text. The ß-actin loading control is also shown.

Effects of terfenadine and loratadine on expression of KIT in neoplastic MC

The oncogenic kinase receptor KIT is constitutively activated and serves as a potential therapeutic target in neoplastic MC. We were therefore interested to learn whether terfenadine and loratadine would interfere with expression of KIT in neoplastic MC. However, under the experimental conditions applied, neither terfenadine nor loratadine were found to reproducibly suppress the expression of KIT in HMC-1 cells as determined by flow cytometry (not shown). We also asked whether terfenadine and/or loratadine would alter the expression of KIT-downstream signaling molecules. In these experiments we found that terfenadine and loratadine downregulate expression of the phosphorylated form of rpS6 in HMC-1 cells, whereas no significant effects on pAkt and pSTAT5 in HMC-1 cells were found (data not shown).

Effects of drug combinations on growth and survival of neoplastic MC

Recent data suggest that combinations of targeted drugs produce cooperative growth-inhibitory effects on neoplastic MC [14-16]. In the present study, dasatinib was found to cooperate with terfenadine (Figure 6A) and loratadine (Figure 6B) in producing apoptosis in HMC-1 cells, and the same cooperative effects were seen when terfenadine or loratadine were combined with PKC412 (Figure 6C and 6D).

Figure 6. Cooperative proapoptotic effects of dasatinib and terfenadine on HMC-1.1 cells.

6A: HMC-1.1 cells were incubated with control medium, dasatinib (1 nM), terfenadine (5 μM), or a combination of both drugs (same concentrations) at 37°C for 24 hours. Then, the numbers (percentage) of apoptotic cells were counted on Giemsa-stained cytospin slides. 6B: HMC-1.1 cells were incubated with control medium, PKC412 (300 nM), terfenadine (5 μM), or a combination of both drugs (same concentrations) at 37°C for 24 hours. After incubation the numbers (percentage) of activated caspase 3-positive cells were determined by flow cytometry. 6C-6F: HMC-1.2 cells were incubated with control medium or various drugs (PKC412, dasatinib, terfenadine, loratadine) as single agents or in combination (at the same concentrations as that used with single agents) at 37°C for 24 hours. Then, the numbers (percentage) of activated caspase 3-positive cells were measured by flow cytometry. Results show the percentage of apoptotic cells assessed by microscopy (6A) or the percentage of active caspase 3-positive cells determined by flow cytometry (6B-F) and represent the mean±S.D. of three independent experiments.

Discussion

Systemic mastocytosis is a hematologic disorder characterized by abnormal growth and survival of neoplastic MC [1-5]. Several different categories of SM including indolent and aggressive variants have been described [1-7]. In ASM and MCL, the prognosis is poor [6,7]. These patients are candidates for cytoreductive agents. In all categories of SM including ASM/MCL, mediator-related symptoms can occur and may represent a challenging problem for the clinician [1-7]. Standard therapy in these patients are HR antagonists [2-7]. Usually, combinations of HR1 and HR2 blockers are prescribed. A hitherto unexplored question was whether HR-antagonists might also produce growth-inhibitory effects on MC. We here show that the HR1 antagonists terfenadine and loratadine suppress the in vitro growth of neoplastic MC. Antineoplastic effects of these drugs were seen in all donors and all species tested, i.e. in human, canine, and feline neoplastic MC.

The effects of terfenadine and loratadine on growth of neoplastic MC were dose-dependent and were specific in that neither the other HR1 blockers nor the HR2, HR3, or HR4 blockers tested produced comparable growth-inhibitory effects in neoplastic MC. An interesting observation was that terfenadine is a more potent agent compared to loratadine, which is consistent with reported effects of these drugs on colon carcinoma cells [19,30,31]. Our data suggest that pharmacologically active concentrations in vivo would only be reached with terfenadine but not with loratadine in mastocytoma patients. Moreover, terfenadine and loratadine may produce side effects even at pharmacologic concentrations. Therefore, current research is attempting to identify more effective and less toxic drug derivatives. In this regard it is noteworthy, that desloratadine, a highly potent derivative of loratadine, also inhibits growth of neoplastic MC (unpublished observation).

An interesting observation was that the effects of terfenadine and loratadine on HMC-1.2 cells are slightly stronger compared to effects obtained with HMC-1.1 cells. This observation was somehow unexpected because HMC-1.2 cells bear KIT D816V, a mutant that introduces resistance against various targeted drugs. The observation is also of importance as KIT D816V is expressed in neoplastic MC in almost all patients with SM [32-35]. Indeed, terfenadine and loratadine produced growth inhibition in primary neoplastic cells derived from patients with KIT D816V+ SM. In addition, terfenadine and loratadine produced clear growth-inhibitory effects on canine mastocytoma C2 cells known to express an activating KIT duplication in exon 11 [36], on NI-1 cells exhibiting an exon 8 KIT mutation, on primary neoplastic canine MC exhibiting a KIT exon 11 polymorphism, and on feline neoplastic MC carrying an exon 8 KIT ITD [37]. All in all, our data suggest that terfenadine and loratadine act growth-inhibitory on neoplastic MC independent of the species analyzed or the presence of disease-associated (often KIT-activating) mutations in the KIT proto-oncogene.

We were also interested to learn whether terfenadine or loratadine would modify expression or activation of KIT in neoplastic MC. However, neither terfenadine nor loratadine were found to alter expression of KIT in human or canine neoplastic MC, suggesting that the mechanism of action of terfenadine and loratadine on neoplastic MC are exerted independent of KIT.

We next asked whether terfenadine and loratadine would induce apoptosis in malignant cells. Our results show that both HR1 antagonists produce apoptosis in neoplastic MC. Apoptosis-inducing effects of terfenadine and loratadine were dose-dependent and were demonstrable by light microscopy, Annexin V staining, and in a Tunel assay. In addition, we were able to show that both HR1 blockers induce caspase activation in neoplastic MC. These data suggest that the growth-inhibitory effects of terfenadine and loratadine are associated with induction of apoptosis in neoplastic MC, which is consistant with effects of these drugs in other cancer cells [19,30,31].

Although apoptosis appears to be involved, the exact biochemical basis for the growth-inhibitory effects of terfenadine and loratadine on neoplastic MC remains at present unknown. An interesting aspect in this regard is that HMC-1 cells as well as normal MC express HR1, HR2, and HR4 [38]. However, although neoplastic MC express HR1, HR1 may not be critical targets, as other HR1 blockers tested did not exert growth-inhibitory effects on MC. An alternative explanation would be that terfenadine and loratadine act on additional (undiscovered) HR or other molecular targets in neoplastic MC. Likewise, a number of previous and more recent data suggest that certain CYP450 isoenzymes serve as potential targets of terfenadine and loratadine and thus are mediating anti-neoplastic effects of these agents [22,39-43]. If so, one could speculate that the other HR blockers tested did not interact with such enzymes in the same way or interact only with other CYP450 variants. This hypothesis would be supported by the notion that fexofenadine, a terfenadine-metabolite that is generated by ‘CYP450-terfenadine’ interactions, but does not bind to CYP450, did not produce growth inhibitory effects on MC in this study.

Another interesting concept is that histamine and histamine-metabolizing enzymes, both of which may interact with CYP450 isoenzymes, regulate the growth and survival of neoplastic cells in various tumors [39-43]. Some of these interactions may also point to autocrine or intercrine growth regulation in neoplastic cells [39-43]. Since MC produce and contain considerable amounts of histamine it might be tempting to speculate that some of the HR blockers disrupt such autocrine or intercrine pathways involving histamine and histamine-binding molecules in neoplastic MC. Further work is required to define the exact mechanism of action of terfenadine and loratadine on intracellular pathways and growth of neoplastic MC.

Another potential mechanism of HR1-induced growth inhibition that has been discussed recently is targeting of cell cycle progression [19,30,31]. Likewise, it has been described that terfenadine and loratadine produce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in cancer cells [30,31]. However, we were unable to demonstrate effects of terfenadine or loratadine on cell cycle distribution in neoplastic MC (unpublished data).

Advanced forms of SM usually are resistant against various conventional and targeted drugs [1-7]. For these patients, combination therapy using established inhibitors of KIT D816V (e.g. PKC412 or dasatinib) may be an attractive approach [14-16]. In the present study, we found that PKC412 and dasatinib cooperate with terfenadine and loratadine in producing apoptosis in HMC-1 cells, which is of interest as HR blockers are commonly used as medication in patients with ASM or MCL.

In conclusion, our data show that terfenadine and loratadine, in addition to their histamine receptor blocking effects, exert growth-inhibitory effects on neoplastic MC carrying transforming KIT mutations. Whether these effects can be reproduced in vivo in patients with ASM or MCL remains to be determined in clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

Supported by: Von Fircks-Fonds and a cooperation-grant of the Clinic for Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases, Veterinary University of Vienna; Fonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung in Österreich - FWF grants #P21173-B13 and #SFB-F01820; the Austrian Federal Ministry for Science and Research (GEN-AU program); and grant #20030 from CeMM – Center of Molecular Medicine, Austrian Academy of Sciences.

References

- 1.Valent P. Biology, classification and treatment of human mastocytosis. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1996;108:385–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Escribano L, Akin C, Castells M, Orfao A, Metcalfe DD. Mastocytosis: current concepts in diagnosis and treatment. Ann Hematol. 2002;81:677–690. doi: 10.1007/s00277-002-0575-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valent P, Akin C, Sperr WR, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of systemic mastocytosis: state of the art. Br J Haematol. 2003;122:695–717. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akin C, Metcalfe DD. Systemic mastocytosis. Annu Rev Med. 2004;55:419–432. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.55.091902.103822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Metcalfe DD. Mast cells and mastocytosis. Blood. 2008;112:946–956. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-078097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valent P, Horny H-P, Escribano L, et al. Diagnostic criteria and classification of mastocytosis: a consensus proposal. Conference Report of “Year 2000 Working Conference on Mastocytosis”. Leuk Res. 2001;25:603–625. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(01)00038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valent P, Horny H-P, Li CY, et al. Mastocytosis (Mast cell disease) In: Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW, editors. World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours. Pathology & Genetics. Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Vol. 1. 2001. pp. 291–302. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kluin-Nelemans HC, Jansen JH, Breukelman H, et al. Response to interferon alfa-2b in a patient with systemic mastocytosis. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:619–623. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202273260907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tefferi A, Pardanani A. Clinical, genetic, and therapeutic insights into systemic mast cell disease. Curr Opin Hematol. 2004;11:58–64. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200401000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kluin-Nelemans HC, Oldhoff JM, Van Doormaal JJ, et al. Cladribine therapy for systemic mastocytosis. Blood. 2003;102:4270–4276. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valent P, Ghannadan M, Akin C, et al. On the way to targeted therapy of mast cell neoplasms: identification of molecular targets in neoplastic mast cells and evaluation of arising treatment concepts. Eur J Clin Invest. 2004;34:41–52. doi: 10.1111/j.0960-135X.2004.01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gotlib J, Berubé C, Growney JD, et al. Activity of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor PKC412 in a patient with mast cell leukemia with the D816V KIT mutation. Blood. 2005;106:2865–2870. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah NP, Lee FY, Luo R, Jiang Y, Donker M, Akin C. Dasatinib (BMS-354825) inhibits KITD816V, an imatinib-resistant activating mutation that triggers neoplastic growth in most patients with systemic mastocytosis. Blood. 2006;108:286–291. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-3969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gleixner KV, Mayerhofer M, Aichberger KJ, et al. PKC412 inhibits in vitro growth of neoplastic human mast cells expressing the D816V-mutated variant of KIT: comparison with AMN107, imatinib, and cladribine (2CdA), and evaluation of cooperative drug effects. Blood. 2005;107:752–759. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gleixner KV, Rebuzzi L, Mayerhofer M, et al. Synergistic antiproliferative effects of KIT tyrosine kinase inhibitors on neoplastic canine mast cells. Exp Hematol. 2007;35:1510–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gleixner KV, Mayerhofer M, Sonneck K, et al. Synergistic growth-inhibitory effects of two tyrosine kinase inhibitors, dasatinib and PKC412, on neoplastic mast cells expressing the D816V-mutated oncogenic variant of KIT. Haematologica. 2007;92:1451–1459. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verstovsek S, Tefferi A, Cortes J, et al. Phase II study of dasatinib in Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute and chronic myeloid diseases, including systemic mastocytosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3906–3915. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ustun C, Corless CL, Savage N, et al. Chemotherapy and dasatinib induce long-term hematologic and molecular remission in systemic mastocytosis with acute myeloid leukemia with KIT D816V. Leuk Res. 2009;33:735–741. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu JD, Wang YJ, Chen CH, et al. Molecular mechanisms of Go/G1 cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis induced by Terfenadine in human cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2003;37:39–50. doi: 10.1002/mc.10118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jangi SM, Diaz-Perez JL, Ochoa-Lizarralde B, et al. H1 histamine receptor antagonists induce genotoxic and caspase-2-dependent apoptosis in human melanoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1787–1796. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rajendra S, Mulcahy H, Patchett S, et al. The effect of H2 antagonists on proliferation and apoptosis in human colorectal cancer cell lines. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:1634–1640. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000043377.30075.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aichberger KJ, Mayerhofer M, Vales A, et al. The CML-related oncoprotein BCR/ABL induces expression of histidine decarboxylase (HDC) and the synthesis of histamine in leukemic cells. Blood. 2006;108:3538–3547. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-028456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butterfield JH, Weiler D, Dewald G, Gleich GJ. Establishment of an immature mast cell line from a patient with mast cell leukemia. Leuk Res. 1988;12:345–355. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(88)90050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akin C, Brockow K, D’Ambrosio C, et al. Effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 on human mast cells bearing wild-type or mutated forms of c-kit. Exp Hematol. 2003;31:686–692. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(03)00112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeVinney R, Gold WM. Establishment of two dog mastocytoma cell lines in continuous culture. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1990;3:413–420. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/3.5.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirkina I, Schweighoffer T, Kricek F. Inhibition of human cord blood-derived mast cell responses by anti-Fc epsilon RI mAb 15/1 versus anti-IgE Omalizumab. Immunol Lett. 2007;109:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valent P, Ashman LK, Hinterberger W, et al. Mast cell typing: demonstration of a distinct hematopoietic cell type and evidence for immunophenotypic relationship to mononuclear phagocytes. Blood. 1989;73:1778–1785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rebuzzi L, Willmann M, Sonneck K, et al. Detection of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and VEGF receptors Flt-1 and KDR in canine mastocytoma cells. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2007;115:320–333. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Cruchten S, Van Den Broeck W. Morphological and biochemical aspects of apoptosis, oncosis and necrosis. Anat Histol Embryol. 2002;31:214–223. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0264.2002.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen C, Li G, Liao W, et al. Selective inhibitors of CYP2J2 related to terfenadine exhibit strong activity against human cancers in vitro and in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:908–918. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.152017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen JS, Lin SY, Tso WL, et al. Checkpoint kinase 1-mediated phosphorylation of Cdc25C and bad proteins are involved in antitumor effects of loratadine-induced G2/M phase cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis. Mol Carcinog. 2006;45:461–478. doi: 10.1002/mc.20165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagata H, Worobec AS, Oh CK, et al. Identification of a point mutation in the catalytic domain of the protooncogene c-kit in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients who have mastocytosis with an associated hematologic disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 1995;92:10560–10564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Longley BJ, Tyrrell L, Lu SZ, et al. Somatic c-kit activating mutation in urticaria pigmentosa and aggressive mastocytosis: establishment of clonality in a human mast cell neoplasm. Nat Genet. 1996;12:312–314. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fritsche-Polanz R, Jordan JH, Feix A, et al. Mutation analysis of C-KIT in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes without mastocytosis and cases of systemic mastocytosis. Br J Haematol. 2001;113:357–364. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feger F, Ribadeau Dumas A, Leriche L, Valent P, Arock M. Kit and c-kit mutations in mastocytosis: a short overview with special reference to novel molecular and diagnostic concepts. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2002;127:110–114. doi: 10.1159/000048179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma Y, Longley BJ, Wang X, Blount JL, Langley K, Caughey GH. Clustering of activating mutations in c-KIT’s juxtamembrane coding region in canine mast cell neoplasms. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;112:165–170. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hadzijusufovic E, Peter B, Rebuzzi L, et al. Growth-inhibitory effects of four tyrosine kinase inhibitors on neoplastic feline mast cells exhibiting a Kit exon 8 ITD mutation. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2009.05.007. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lippert U, Artuc M, Grützkau A, et al. Human skin mast cells express H2 and H4, but not H3 receptors. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:116–123. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Radvány Z, Darvas Z, Kerekes K, et al. H1 histamine receptor antagonist inhibits constitutive growth of Jurkat T cells and antigen-specific proliferation of ovalbumin-specific murine T cells. Semin Cancer Biol. 2000;10:41–45. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2000.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malaviya R, Uckun FM. Histamine as an autocrine regulator of leukemic cell proliferation. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000;36:367–373. doi: 10.3109/10428190009148858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rivera ES, Cricco GP, Engel NI, Fitzsimons CP, Martín GA, Bergoc RM. Histamine as an autocrine growth factor: an unusual role for a widespread mediator. Semin Cancer Biol. 2000;10:15–23. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2000.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Falus A, Hegyesi H, Lázár-Molnár E, Pós Z, László V, Darvas Z. Paracrine and autocrine interactions in melanoma: histamine is a relevant player in local regulation. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:648–652. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Darvas Z, Sakurai E, Schwelberger HG, et al. Autonomous histamine metabolism in human melanoma cells. Melanoma Res. 2003;13:239–246. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200306000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]