Abstract

Proposed quantum networks require both a quantum interface between light and matter and the coherent control of quantum states1,2. A quantum interface can be realized by entangling the state of a single photon with the state of an atomic or solid-state quantum memory, as demonstrated in recent experiments with trapped ions3,4, neutral atoms5,6, atomic ensembles7,8, and nitrogen-vacancy spins9. The entangling interaction couples an initial quantum memory state to two possible light–matter states, and the atomic level structure of the memory determines the available coupling paths. In previous work, these paths’ transition parameters determine the phase and amplitude of the final entangled state, unless the memory is initially prepared in a superposition state4, a step that requires coherent control. Here we report the fully tunable entanglement of a single 40Ca+ ion and the polarization state of a single photon within an optical resonator. Our method, based on a bichromatic, cavity-mediated Raman transition, allows us to select two coupling paths and adjust their relative phase and amplitude. The cavity setting enables intrinsically deterministic, high-fidelity generation of any two-qubit entangled state. This approach is applicable to a broad range of candidate systems and thus presents itself as a promising method for distributing information within quantum networks.

Optical cavities are often proposed as a means to improve the efficiency of atom-photon entanglement generation. Experiments using single emitters3-5,9 collect photons over a limited solid angle, with only a small fraction of entanglement events detected. However, by placing the emitter inside a low-loss cavity, it is possible to generate photons with near-unit efficiency in the cavity mode1,10. Neutral atoms in a resonator have been used to generate polarization-entangled photon pairs6,11, but this has not yet been combined with coherent operations on the atomic state. Trapped ions have the advantage of well-developed methods for coherent state manipulation and readout12,13. Using a single trapped ion integrated with a high-finesse cavity, we implement full tomography of the joint atom-photon state and generate maximally entangled states with fidelities up to 97.4(2) %.

In initial demonstrations of atom-photon entanglement, the amplitudes of the resulting state are fixed by atomic transition amplitudes3,5,6,9,11. If the final atomic states are not degenerate, as in the case of a Zeeman splitting, the phase of the atomic state after photon detection is determined by the time at which detection occurs. In contrast, we control both amplitude and phase via two simultaneous cavity-mediated Raman transitions. The bichromatic Raman fields ensure the independence of the atomic state from the photon-detection time; their relative amplitude and phase determine the state parameters. Within a quantum network, such a tunable state could be matched to any second state at a remote node, generating optimal long-distance entanglement in a quantum-repeater architecture14.

A tunable state has previously been employed as the building block for teleportation4 and a heralded gate between remote qubits15. In this case, tunability of the entangled state is inherited from control over the initial state of the atom. The photonic qubit is encoded in frequency, and as a result, integration with a cavity would be technically challenging. The entangling process is intrinsically probabilistic, with efficiency limited to 50% even if all emitted photons could be collected. In the scheme presented here, the entangling interaction itself is tunable, and no coherent manipulation of the input state is required. For atomic systems with a complex level scheme in which several transition paths are possible, the two most suitable paths can be selected.

Our experimental apparatus (Fig. 1(a)) consists of a linear Paul trap storing a single 40Ca+ ion within a 2 cm optical cavity16,17. The cavity has a waist of 13 μm and finesse of 77,000 at 854 nm, the wavelength of the 42P3/2 − 32D5/2 transition. The rates of coherent atom-cavity coupling g, cavity-field decay κ, and atomic polarization decay γ are given by (g, κ, γ) = 2π × (1.4, 0.05, 11.2) MHz. The ion is located in both the waist and in an antinode of the cavity standing wave, and it is localized to within 13 ± 7 nm along the cavity axis17. Entanglement is generated via a bichromatic Raman field at 393 nm and read out using a quadrupole field at 729 nm.

Figure 1. Experimental apparatus and entanglement sequence.

a, An ion is confined in a Paul trap (indicated by two endcaps) at the point of maximum coupling to a high-finesse cavity. A 393-nm laser generates atom-photon entanglement, characterized using a 729-nm laser. Photons’ polarization exiting the cavity is analyzed using half- and quarter-waveplates (L/2, L/4), a polarizing beamsplitter cube (PBS), and fiber-coupled avalanche photodiodes (APD0, APD1). b, A bichromatic Raman pulse with Rabi frequencies Ω1, Ω2 and detunings Δ1, Δ2 couples |S〉 to states |D〉 and |D′〉 via two cavity modes H and V (1), generating a single cavity photon. To read out entanglement, |D′〉 is mapped to |S〉 (2), and coherent operations on the S – D transition (3) prepare the ion for measurement.

A magnetic field of 2.96 G is applied along the quantization axis and perpendicular to the cavity axis. The cavity supports degenerate horizontal (H) and vertical (V) polarization modes, where H is defined parallel to . At the cavity output, the modes are separated on a polarizing beamsplitter and detected at avalanche photodiodes. A half- and a quarter-waveplate prior to the beamsplitter allow us to set the measurement basis of the photon18.

The entangling process is illustrated in Fig. 1(b). Following a Doppler-cooling interval, the ion is initialized via optical pumping in the state |S〉 ≡ |42S1/2, mS = −1/2〉. In order to couple |S〉 simultaneously to the two states |D〉 ≡ |32D5/2, mD = −3/2〉 and |D′〉 ≡ |32D5/2, mD = −5/2〉, we apply a phase-stable bichromatic Raman field, detuned by Δ1 and Δ2 from the |S〉 − |P 〉 transition. Here, the intermediate state |P〉 ≡ |42P3/2, mP = −3/2〉 is used. The cavity is stabilized at detuning MHz from the |P〉 − |D〉 transition and from the |P〉−|D′〉 transition, where ΔD,D′ is the Zeeman splitting between |D〉 and |D′〉. When and Δi satisfy the Raman resonance condition for both i = (1, 2), population is transferred coherently from |S〉 to both |D〉 and |D′〉, and a single photon is generated in the cavity19-22.

The effective coupling strength of each of the two transitions is given by . Here, Ω1 and Ω2 are the amplitudes of the Raman fields; G1 and G2 are the products of the Clebsch-Gordon coefficients and the projections of laser and vacuum-mode polarizations onto the atomic dipole moment17. In free space, these two pathways generate π- and σ+-polarized photons, respectively. Within the cavity, the π photon is projected onto H and the σ+ photon onto V 16,17. Ideally, the bichromatic fields generate any state of the form

where and φ is determined by the relative phase of the Raman fields. To determine the the overlap of the measured state with |ψ〉, we perform quantum state tomography of the ion-photon density matrix ρ for given values of α and φ. Ion and photon are measured in all nine combinations of ion Pauli bases {σx, σy, σz} and photon polarization bases {H/V, diagonal/antidiagonal, right/left}18.

In order to measure the ion in all three bases, we first map the superposition of {D′, D} onto the {S, D} states12,13. We then perform additional coherent operations to select the measurement basis and discriminate between S and D via fluorescence detection13. Each sequence lasts 1.5 ms and consists of 800 μs of Doppler cooling, 60 μs of optical pumping, a 40 μs Raman pulse, an 4 μs mapping pulse, an optional 4.3 μs rotation, and 500 μs of fluorescence detection. The probability to detect a photon in a single sequence is 5.7%; we thus detect on average 40.5 events/s. Note that the photon is generated with near-unit efficiency, and detection is primarily limited by the probability for the photon to exit the cavity (16%) and the photodiode efficiencies (40%).

In a first set of measurements, we choose the case α = π/4, corresponding to a maximally entangled state |ψ〉. From the tomographic data, the density matrix is reconstructed as shown in Fig. 2(a). Here we have tuned Ω1 and Ω2 so as to produce both photon polarizations with equal probability, corresponding to maximal overlap of the temporal pulse shapes of H and V photons (Fig. (b)). In order to demonstrate that the photon-detection time does not determine the phase of the state, we extract this phase from state tomography as a function of the photon time bin (Fig. 2(c)). Because the frequency difference of the bichromatic fields Δ1 − Δ2 is equal to the level spacing between |D〉 and |D′〉, the phase φ = 0.25π remains constant. Further details are given in the Methods section.

Figure 2. Quantum state tomography of the joint ion-photon state, containing ~ 40, 000 events.

a, Real and imaginary parts of all density matrix elements for Raman phase φ = 0.25, from which a fidelity F = 97.4(2) % is calculated. Colors for the density matrix elements correspond to those used in Figs. 3a and 4a. b, Temporal pulse shape of H and V cavity photons. Error bars represent one s.d. based on Poissonian photon statistics. c, Phase of the ion-photon state vs. photon-detection time. Arrows indicate time-bin intervals of the tomography data. Error bars represent one s.d. (see Methods).

Tomography over all time bins yields a fidelity of F ≡ 〈ψ|ρ|ψ〉 = 97.4(2) % with respect to the maximally entangled state, placing our system definitively in the nonclassical regime F > 50%. Another two-qubit entanglement witness is the concurrence23, which we calculate to be 95.2(5) %. The observed entanglement can also be used to test local hidden-variable models (LHVMs) via the violation of the Clauser-Horne-Shimony-Holt (CHSH) Bell inequality24. Entanglement of a hybrid atom-photon system holds particular interest since it could be used for a loophole-free test of a Bell-type inequality25. While LHVMs require the Bell observable of the CHSH-inequality to be less than 2, we measure a value 2.75(1)> 2, where quantum mechanics provides an upper bound of .

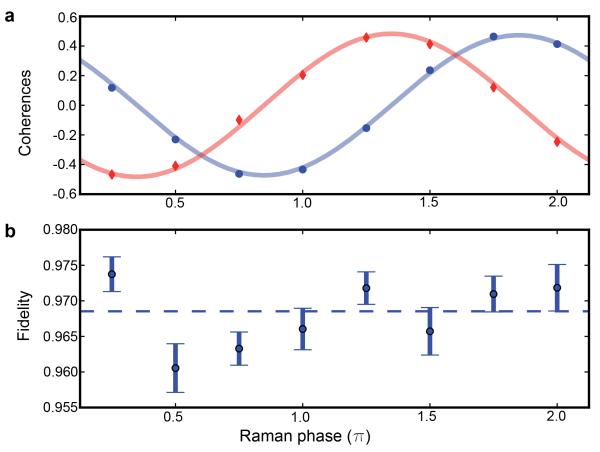

We now establish that we can prepare |ψ〉 with high fidelity over the full range of the Raman phase φ. We repeat state tomography for seven additional values of the relative Raman phase. As a function of φ, the real and imaginary parts of the coherence ρ14 ≡ 〈DH|ρ|D′V〉 vary sinusoidally as expected (Fig. 3(a)). The fidelity has a mean value of 96.9(1) % and does not vary within error bars over all target phases (Fig. 3(c)).

Figure 3. State tomography as a function of Raman phase (~ 340, 000 events).

a, Re(ρ14) (blue circles) and Im(ρ14) (red diamonds) as a function of Raman phase. Errorbars are smaller than the size of the symbols. Each value is extracted from a full state tomography of ρ as in Fig 2a. Both curves are fitted simultaneously, with phase offset constrained to π/2. The fit contrast is 95.6(4)%. b, Fidelities of the eight states, with a dashed line indicating the mean value. Error bars represent one s.d. (see Methods).

A second measurement set demonstrates control over the amplitudes cos α and sin α of the entangled ion-photon state. After selecting three target amplitudes , we generate each corresponding state by adjusting the Raman field amplitudes, since α is a function of the ratio Ω2/Ω1. The density matrix for each state is then measured. In Fig. 4(a), we see that the populations ρ11 ≡ 〈DH|ρ|DH〉 and ρ44 ≡ 〈D′V|ρ|D′V〉 for the three target amplitudes agree well with theoretical values. The fidelities of the asymmetric states (Fig. 4(b)) are as high as those of the maximally entangled states and are limited by the populations, that is, by errors in tuning the Raman fields to match the target values.

Figure 4. State tomography for three values of amplitude cos α.

a, The density matrix elements ρ11 (orange squares) and ρ44 (green triangles) are plotted for the three target amplitudes . Errorbars are smaller than the size of the symbols. Solid lines represent the amplitudes of the target states. b, The corresponding fidelities are F = {96.3(3), 96.8(3), 98.0(4)}. A dashed line indicates the mean value. Error bars represent one s.d. (see Methods).

Errors in atomic state detection5,25, atomic decoherence11 and multiple excitations of the atom3 reduce the fidelity of the atom-photon entangled state by ≪ 1%. Imperfect initialization and manipulation of the ion due to its finite temperature and laser intensity fluctuations decrease the fidelity by 1%. The two most significant reductions in fidelity are due to dark counts of the APDs at a rate of 36 Hz (1.5%) and imperfect overlap of the temporal pulse shapes (1%).

To our knowledge, this measurement represents both the highest fidelity and the fastest rate of entanglement detection to date between a photon and a single-emitter quantum memory. This detection rate is limited by the fact that most cavity photons are absorbed or scattered by the mirror coatings, and only 16% enter the output mode. However, using mirrors with state-of-the-art losses and a highly asymmetric transmission ratio, an output coupling efficiency exceeding 99% is possible (see Methods). In contrast, without a cavity, using a lens of numerical aperture 0.5 to collect photons, the efficiency would be 6.7%. In addition, the infrared wavelength of the output photons is well-suited to fiber distribution, enabling long distance quantum networks. We note that a faster detection rate could be achieved by triggering ion-state readout on the detection of a photon.

We have demonstrated full control of the phase and amplitude of an entangled ion-photon state, which opens up new possibilities for quantum communication schemes. In contrast to monochromatic schemes, evolution of the relative phase of the atomic state after photon detection is determined only by the start time of the experiment and not by the photon-detection time. The state |ψ〉 is in this sense predetermined and can be stored in, or extracted from, a quantum memory in a time-independent manner. The bichromatic Raman process employed here provides a basis for a coherent atom-photon state mapping as well as one- or two-dimensional cluster state generation26.

Methods

Detection and state tomography

The cavity output path branches at a polarizing beamsplitter into two measurement paths, and the detection efficiencies of these paths are unequal. We compensate for this imbalance by performing two measurements for a given choice of ion and photon basis and sum the results; between the measurements, a rotation of the output waveplates swaps the two paths.

At each measurement setting, we record on average 4722 events in which a single photon has been detected. While a photon is detected in 5.7% of sequences, the atom is always measured. Correlations of the photon polarization and the atomic state are the input for maximum likelihood reconstruction of the most likely states27. Error bars are one standard deviation derived from non-parametric bootstrapping28 assuming a multinomial distribution.

Time independence

The phase of the entangled atom-photon state is inferred from the measurements of photon polarization and atomic-state phase. In the experiments of Refs.3,6,9, although the phase of the entangled state is time independent before photon detection, the phase of the atomic state after photon detection evolves due to Larmor precession. It is thus necessary to fix the time between photon detection and atomic state readout in order to measure the same φ for all realizations of the experiment. In contrast, for the case of Raman fields Ω1eiω1t and Ω2eiω2t, the correct choice of frequency ω1 − ω2 = ωD′ − ωD means that both the phase of the entangled atom-photon state before photon detection and the phase of the atomic state after photon detection are independent of photon-detection time.

We define a model system with bases {|S, n〉, |D, n〉, |D′, n〉}, where n = {0, 1} is the photon number in either of the two degenerate cavity modes. The excited state has been adiabatically eliminated, so that couples |S, 0〉 to |D, 1〉 and couples |S, 0〉 to |D′, 1〉). After transformation into a rotating frame U = eiω1t|S〉 〈S| ei(ω1−ω2)t|D′〉 〈D′|, the Hamiltonian is

where ħ = 1, {ωS; ωD; ωD′} are the state frequencies, ωC is the cavity frequency, and terms rotating at are omitted.29 In this frame, the couplings are time-independent, and the states |D〉 and |D′〉 are degenerate. Therefore, the phase between |D, 1〉 and |D′, 1〉 remains fixed during Raman transfer, and the phase between |D, 0〉 and |D′, 0〉 stays constant after photon detection.

Cavity parameters

The cavity mirrors have transmission T1 = 13 ppm and T2 = 1:3 ppm, with combined losses of 68 ppm. State-of-the-art combined losses at this wavelength are L = 4 ppm30. In our cavity, these losses would correspond to an output coupling efficiency of T1=(T1+T2+L) = 71%. To improve this efficiency, an output mirror with higher transmission T1 could be used; for example, T1 = 500 ppm corresponds to an efficiency of 99%. The cavity decay rate κ would also increase, but single-photon generation with near-unit efficiency is valid in the bad-cavity regime10

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Barreiro, D. Nigg, K. Hammerer, and W. Rosenfeld for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), the European Commission (AQUTE), the Institut für Quanteninformation GmbH, and a Marie Curie International Incoming Fellowship within the 7th European Framework Program.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Cirac JI, Zoller P, Kimble HJ, Mabuchi H. Quantum state transfer and entanglement distribution among distant nodes in a quantum network. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997;78:3221–3224. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kimble HJ. The quantum internet. Nature. 2008;453:1023–1030. doi: 10.1038/nature07127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blinov BB, Moehring DL, Duan LM, Monroe C. Observation of entanglement between a single trapped atom and a single photon. Nature. 2004;428:153–157. doi: 10.1038/nature02377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olmschenk S, et al. Quantum teleportation between distant matter qubits. Science. 2009;323:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1167209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volz J, et al. Observation of entanglement of a single photon with a trapped atom. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;96:030404. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.030404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilk T, Webster SC, Kuhn A, Rempe G. Single-atom single-photon quantum interface. Science. 2007;317:488–490. doi: 10.1126/science.1143835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsukevich DN, et al. Entanglement of a photon and a collective atomic excitation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005;95:040405. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.040405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sherson J, et al. Quantum teleportation between light and matter. Nature. 2006;443:557–560. doi: 10.1038/nature05136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Togan E, et al. Quantum entanglement between an optical photon and a solid-state spin qubit. Nature. 2010;466:730–734. doi: 10.1038/nature09256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Law C, Kimble H. Deterministic generation of a bit-stream of single-photon pulses. J. Mod. Opt. 1997;44:2067–2074. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weber B, et al. Photon-photon entanglement with a single trapped atom. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009;102:030501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.030501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leibfried D, Blatt R, Monroe C, Wineland D. Quantum dynamics of single trapped ions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2003;75:281–324. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ḧaffner H, Roos C, Blatt R. Quantum computing with trapped ions. Physics Reports. 2008;469:155–203. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Briegel H-J, Dür W, Cirac JI, Zoller P. Quantum repeaters: The role of imperfect local operations in quantum communication. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998;81:5932–5935. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maunz P, et al. Heralded quantum gate between remote quantum memories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009;102:250502. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.250502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russo C, et al. Raman spectroscopy of a single ion coupled to a high-finesse cavity. Appl. Phys. B. 2009;95:205–212. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stute A, et al. Toward an ion–photon quantum interface in an optical cavity. Appl. Phys. B. 2011 10.1007/s00340-011-4861-0. [Google Scholar]

- 18.James DFV, Kwiat PG, Munro WJ, White AG. Measurement of qubits. Phys. Rev. A. 2001;64:052312. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKeever J, et al. Deterministic generation of single photons from one atom trapped in a cavity. Science. 2004;303:1992–1994. doi: 10.1126/science.1095232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keller M, Lange B, Hayasaka K, Lange W, Walther H. Continuous generation of single photons with controlled waveform in an ion-trap cavity system. Nature. 2004;431:1075–1078. doi: 10.1038/nature02961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hijlkema M, et al. A single-photon server with just one atom. Nat. Phys. 2007;3:253–255. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barros HG, et al. Deterministic single-photon source from a single ion. New J. Phys. 2009;11:103004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wootters WK. Entanglement of formation of an arbitrary state of two qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998;80:2245–2248. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clauser JF, Horne MA, Shimony A, Holt RA. Proposed experiment to test local hidden-variable theories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1969;23:880–884. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenfeld W, et al. Towards a loophole-free test of Bell’s inequality with entangled pairs of neutral atoms. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2009;2:469–474. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Economou SE, Lindner N, Rudolph T. Optically generated 2-dimensional photonic cluster state from coupled quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010;105:093601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.093601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ježek M, Fiurášek J, Hradil Z. Quantum inference of states and processes. Phys. Rev. A. 2003;68:012305. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davison A, Hinkley D. Bootstrap methods and their application. Cambridge Univ. Press; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shore B. The Theory of Coherent Atomic Excitation. Wiley; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rempe G, Thompson RJ, Brecha RJ, Lee WD, Kimble HJ. Optical bistability and photon statistics in cavity quantum electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1991;67:1727–1730. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.67.1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]