Abstract

Rationale

Myocardial infarction (MI) is a leading cause of death in developed nations, and there remains a need for cardiac therapeutic systems that mitigate tissue damage and. Cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs) and other stem cell types are attractive candidates for treatment of MI; however, the benefit of these cells may be due to paracrine effects.

Objective

We tested the hypothesis that CPCs secrete pro-regenerative exosomes in response to hypoxic conditions.

Methods and Results

The angiogenic and anti-fibrotic potential of secreted exosomes on cardiac endothelial cells and cardiac fibroblasts were assessed. We found that CPC exosomes secreted in response to hypoxia enhanced tube formation of endothelial cells and decreased pro-fibrotic gene expression in TGF-β stimulated fibroblasts, indicating that these exosomes possess therapeutic potential. Microarray analysis of exosomes secreted by hypoxic CPCs identified eleven miRNAs that were upregulated compared to exosomes secreted by CPCs grown under normoxic conditions. Principle component analysis was performed to identify miRNAs that were co-regulated in response to distinct exosome generating conditions. To investigate the cue-signal-response relationships of these miRNA clusters with a physiological outcome of tube formation or fibrotic gene expression, partial least squares regression analysis was applied. The importance of each up- or downregulated miRNA on physiological outcomes was determined. Finally, to validate the model we delivered exosomes following ischemia-reperfusion injury. Exosomes from hypoxic CPCs improved cardiac function and reduced fibrosis.

Conclusions

These data provide a foundation for subsequent research of the use of exosomal miRNA and systems biology as therapeutic strategies for the damaged heart.

Keywords: Exosomes, myocardial infarction, microRNA, cardiac progenitor cells, systems biology, modeling

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in developed nations, and acute myocardial infarction is a major contributor to poor outcomes, particularly in the U.S. and other developed nations1. Beyond the acute treatment of restoring blood flow to hypoxic myocardium, subsequent measures focus on improving the contractility of non-infarcted tissue. Typically, the damaged, relatively non-regenerative myocardium undergoes a degenerative remodeling process that leads to heart failure. Furthermore, the economic burden of cardiovascular disease is profound. In 2010, costs for cardiovascular disease-related care totaled $315.4 billion, and, by 2030, costs are expected to grow to $918 billion when 43.9% of the population is expected to suffer from CVD1.

Cell-based therapies to treat the damaged heart—including injection of stem cells from various sources—have yielded mixed results in several species2–4. Cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs), a small population of stem-like cells residing in the heart, are of interest as they differentiate into cardiac lineages and can be isolated by tissue biopsy. Induced differentiation of stem cells into various cardiac cell types has shown changes in cell exocytosis in response to different growth conditions5–7. However, whether these changes in stem cell exocytosis have a beneficial impact on the cardiac response through differentiation or paracrine signaling is unknown.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are recognized as important regulators of intracellular gene expression. Recently, they have been discovered extracellularly, in the blood of mammals8. Since then, stable extracellular miRNAs have also been identified in urine, saliva, semen, breast milk, and cerebrospinal fluid8. Furthermore, distinct miRNA profiles in biofluids have been linked to disease pathologies, leading to interest in the use of extracellular miRNAs as disease biomarkers9–11. Extracellular miRNA profiles have already been explored for a range of conditions, including cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases10, 12, 13.

Extracellular miRNAs are protected from degradation by nucleases because they are encapsulated within membrane-derived vesicles (apoptotic bodies, microvesicles, and exosomes), or they form complexes with extracellular proteins8, 12, 14, 15. Recent efforts have been made to explore the endogenous function of circulating miRNAs, especially in intercellular communication and gene regulation8, 16. Interestingly, the miRNA signatures are unique among different carriers14, and between carriers and parent cells, suggesting regulated export of miRNAs14, 17, 18. Exosomes are secreted membrane-bound vesicles, with diameters ranging from 30–130 nm that carry a multitude of signals. Most cells secrete exosomes; those verified include platelets12, lymphocytes16, and adipocytes19, and, muscle10, 20, tumor21, glial22, and stem cells23–25.

In this report, we isolated exosomes from the media of CPCs exposed to hypoxic and normoxic conditions for 3 or 12 hr, and we examined the effects of these exosomes on cardiac cells in vitro and in vivo. We also analyzed exosomal miRNA via array and identified several miRNAs upregulated in response to hypoxia. Using empirical data and statistical transformation processes, we developed a computational model that predicts the effects of hypoxia and normoxia on the miRNA content of exosomes produced by CPCs. Finally, we identified covarying miRNA clusters that may lead to future bio-inspired therapeutics.

METHODS

Cardiac progenitor cell isolation

CPCs were isolated from neonatal adult Sprague-Dawley rats by removing the heart and homogenizing the tissue as described3.

Exosome generation

CPCs were grown to 90% confluence and quiesced for 12 hr. Plated cells were subjected to normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 3 hr or 12 hr. To generate hypoxic conditions, cells were transferred to an incubator chamber (Billups-Rothenberg MIC-101) and flushed with hypoxic gas mixture (95% N2, 5% CO2). After conditioning, the media was subjected to sequential centrifugation (Optima XPN-100 ultracentrifuge; Beckman Coulter SW 41 Ti rotor) at 10,000 × g for 35 min to remove cell debris and 100,000 × g for 70 min., followed by two washings in PBS (100,000 × g, 70 min.). The exosome pellet was isolated and the protein content of the exosome suspension was analyzed by Micro BCA Protein Assay kit (Thermo Scientific Pierce 23235) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Secreted miR analysis

miR was isolated from conditioned media with the miRVANA PARIS kit (Invitrogen AM1556M) according to manufacturer’s protocol. The miR solutions were analyzed (Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer) for size, quality, and quantity of miR. Following characterization, miR was subjected to analysis via Affymetrix MultiSpecies MicroRNA GeneChip array. Data were analyzed in Affymetrix Expression Console to determine levels of miR upregulation.

To evaluate levels of upregulated miR in exosomes, exosomal miR was isolated with the miRVANA PARIS kit and cDNA generated via NCode miRNA First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen MIRC-50) according to manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA samples were then subjected to qRT-PCR and relative mRNA levels ascertained by comparative CT method, with RNU6B as the housekeeping gene. The mean minimal cycle threshold values were calculated from triplicate reactions.

Principle component and partial least squares regression analysis

Principle component and partial least squares regression analysis were performed as described previously40, 41, using the SIMCA-P software (UMetrics) that solves the PLSR problem with the nonlinear iterative partial least squares (NIPALS) algorithm48.

An expanded Methods section is available in the Supplemental Data file.

RESULTS

Verification of exosome internalization

Exosomes were isolated and characterized as described in Supplemental Fig. I. To determine whether cardiac cell types of interest could internalize exosomes derived from CPCs subjected to 12h of hypoxia or normoxia, cardiac endothelial cells and fibroblasts were incubated for 12 hr with Acridine Orange or calcein-labeled exosomes and imaged by confocal microscopy (Fig. 1A and E) or ImageStream flow cytometry (Fig. 1B and F). Internalization of exosomes was confirmed visually by the presence of intracellular punctate fluorescence, and also confocally by localization of exosomes in the same plane as nuclei in z-stacks. Analysis of number of spots per cell revealed no difference in uptake between exosomes from hypoxic or normoxic CPCs in either cell type (Fig. 1C and G). Furthermore, similar findings were observed for average fluorescence intensity per cell (Fig. 1D and H). We also examined uptake of exosomes derived from CPCs subjected to 3h of hypoxia or normoxia and saw similar trends (Supplemental Fig. IIA–F). Uptake by primary rat cardiomyocytes was minimal (Supplemental Fig. IIG).

Figure 1. Cardiac cells internalize CPC exosomes.

Confocal 2D-images (XY) from a central focal plane (with orthogonal XZ and YZ images on the bottom and left, respectively) from a single z-stack and differential interference contrast images of endothelial cells (A) or cardiac fibroblasts (E) with internalized Acridine Orange-stained CPC exosomes (blue=Hoechst, green=Acridine Orange). ImageStream flow cytometry images of cardiac endothelial cells (B) or cardiac fibroblasts (F) with internalized calcein-stained CPC exosomes (green=calcein). No difference was observed in the uptake of exosomes generated in normoxic or hypoxic conditions as evaluated by spots per cell (C and G) or total fluorescence per cell (D and H). >50,000 events were analyzed by IDEAS statistical software. n=6 for C and D, n=4 for G and H. Error bars represent SEM, unpaired t-test comparison. All scale bars = 10μm.

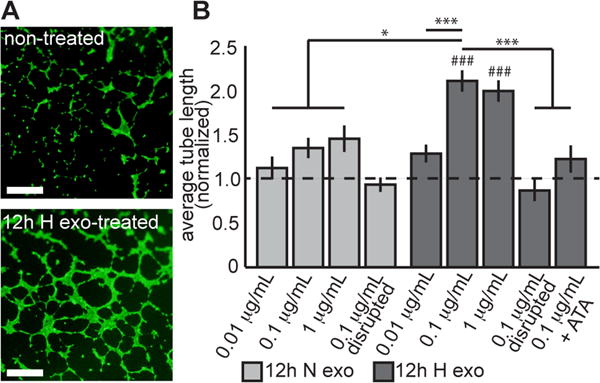

Exosomes from hypoxic CPCs increase tube formation

To determine functional effects of exosomes on endothelial cells, we evaluated whether exosome internalization could induce endothelial tube formation. Cardiac endothelial cells were treated for 24 hr with exosomes from hypoxic or normoxic CPCs and then plated on Geltrex prior to imaging (Fig. 2A). Treatment group tube lengths were normalized to tube formation measured in non-treated cells. While exosomes from normoxic CPCs had no significant effect on tube formation, exosomes from hypoxic CPCs significantly enhanced formation of tube-like structures (Fig. 2B). This response was dependent on exosome dose, and disruption of exosomes from hypoxic CPCs via sonication abrogated the effect. Furthermore, co-treatment with the RISC inhibitor aurintricarboxilic acid (ATA)26 negated the effects of exosomes on tube formation. We also examined angiogenic gene expression in endothelial cells treated with exosomes and found modest changes in response to either exosome treatment (Supplemental Fig. III).

Figure 2. Effects of CPC exosomes on tube formation.

(A) Representative images of blood vessel-like structures stained with calcein on Geltrex. Scale bar = 1 mm. (B) Tube formation relative to non-treated cells. Exosomes secreted by normoxic CPCs had no effect on tube formation, whereas exosomes from hypoxic CPCs increased tube formation in a positive dose-response manner. The effect plateaued after 0.1 ug/ml treatment, which elicited an increase in tube formation 2.1±0.12-fold over non-treated cells (mean±SEM). Negative controls included sonicated disrupted exosome, which elicited no change in tube formation. Co-treatment with RISC-inhibitor ATA neutralized the effect of exosomes from hypoxic CPCs. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001. ###p<0.001 compared to non-treated cells (dotted line).

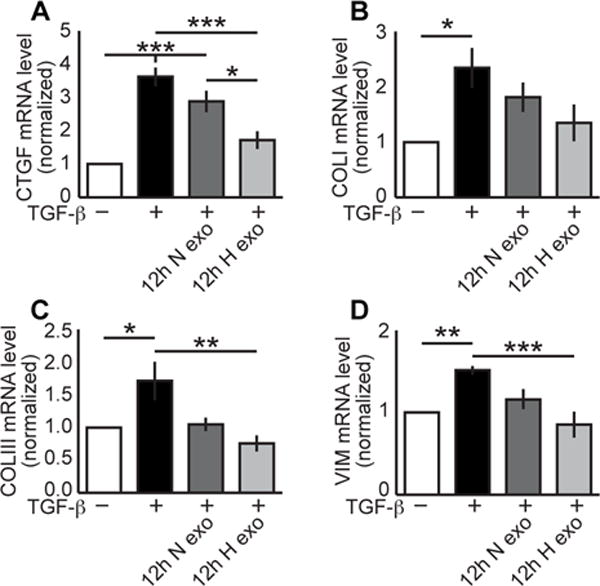

Exosomes from hypoxic CPCs reduce pro-fibrotic genes

To investigate the potential effects of exosomes on fibrotic gene expression, we treated rat cardiac fibroblasts with either exosomes derived from 12h normoxic or hypoxic CPCs prior to stimulation with TGF-β. TGF-β stimulation significantly increased connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), collagen I (COLI), collagen III (COLIII), and vimentin (VIM) gene expression (Fig. 3). We observed no significant decrease in CTGF, COLI, COLIII, or VIM levels following treatment with exosomes from 12h normoxic CPCs, but detected a significant decrease of CTGF (43%), COLIII (56%), and VIM (44%) mRNAs in cells treated with 12h hypoxic exosomes compared to TGF-β stimulation alone. COLI was decreased 42% by 12h hypoxic exosomes but this was not considered statistically significant.

Figure 3. Exosomes generated from hypoxic CPCs in 12h ameliorated cytokine stimulation of fibroblasts.

Whereas TGF-β increased fibrotic gene mRNA levels up to 3.6±0.28-fold (mean±SEM), only treatment with 0.1 ug/mL exosomes from 12h hypoxic CPCs reduced stimulation: CTGF (A) to 1.7±0.27-fold (n=5–9); COLI (B) to 1.3±0.3-fold (n=6); COLIII (C) to 0.75±0.12-fold (n=5); VIM (D) to 0.85±0.16-fold (n=7). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 compared to non-treatment mRNA levels. ANOVA followed by Tukey post-test.

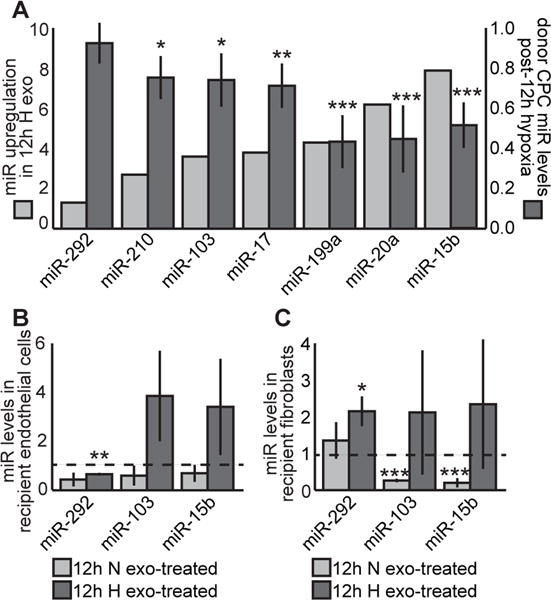

CPC miRNA secretome is altered in response to hypoxia

We isolated the small RNA fraction of CPC conditioned media (3 and 12 hr, normoxia and hypoxia) and performed Affymetrix GeneChip miRNA array. For the 12 hr time point, 11 miRNAs were upregulated 2-fold or more in response to hypoxic conditions. qRT-PCR analysis of small RNA isolated from pooled exosomes validated the upregulation seven of the 11 miRNAs by hypoxia (Fig. 4A dark bars). Interestingly, six of the seven miRNA upregulated in hypoxic exosomes have been previously shown to have a role in cardiac function (Supplemental Fig. IV). Only two of these miRNAs were upregulated in microvesicles (miR-17 and -210).

Figure 4. miRNA levels transferred from donor CPCs in 12h, secreted exosomes, and recipient cells.

(A) qRT-PCR revealed seven miRNAs upregulated in secreted miRNAs from CPCs treated with hypoxia for 12 hr (light bars), and that six of those seven were significantly depleted in donor CPCs (dark bars; n=8). Of the three examined miRNAs, trends suggest an increase in some miRNAs in recipient endothelial cells (B) and fibroblasts (C). In fibroblasts, miR-292 levels increased significantly (n=4) Mean±SEM, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, unpaired t-test, compared to non-treatment levels.

We also examined donor CPC miRNA levels following 12h of normoxia or hypoxia. We observed an inverse relationship between donor intracellular and exosomal miRNA levels (Fig 4A light bars). To determine miRNA transfer, we measured the intracellular levels of three upregulated miRNAs in recipient endothelial cells and fibroblasts (Fig. 4B and C), we observed a 2.1-fold increase of miR-292 in fibroblasts from treatment with 12h hypoxic exosomes. Although not statistically significant, the trend suggests that 12h hypoxic exosomes increased miR-103 and -15b in endothelial cells.

Lack of effect from 3 hour exosomes

We measured transfer of miRNA in recipient endothelial cells and fibroblasts treated with 3h exosomes (Fig. 5A and B). In contrast to 12h exosomes, we found no significant increase of any of the examined miRNAs in recipient cells.

Figure 5. Evaluation of 3h exosomes and validation of computational modeling.

No significant changes in miRNA levels in recipient endothelial cells (A) or fibroblasts (B) were observed (Unpaired t-test; n=3–4. In examining the functional response of treatment with 3h exosomes, only COLI gene expression (D) was significantly reduced. Treatment with 3h hypoxic exosomes reduced COLI mRNA levels from 2.2±0.74 to 0.81±0.29-fold. There was no effect of exosome treatment on CTGF (C), COLIII (E), or vimentin (VIM, F) expression. Exosomes generated in 3 hr did not influence tube formation (G); there was no significant increase with either exosome type. ANOVA followed by Tukey post-test. Mean±SEM, *p<0.05.

Based on earlier models, exosomes generated in 3h of hypoxia or normoxia were not projected to be a potent driver of fibrotic mRNA expression or tube formation. Out of the four fibrotic mRNAs examined (Fig 5C–F), only COLI decreased significantly (64%) when treated with 3h hypoxic exosomes (Fig. 5D). No significant effect on tube formation was observed in cells treated with 3h exosomes (Fig. 5G).

Principle component analysis reveals covarying miRNA clusters

We employed principle component analysis (PCA) of the microarray data to investigate covarying relationships among the miRNAs that were up- or down-regulated after pretreatment conditions. The first principle component (PC) separated the fold change differences from the absolute values of the miRNA levels, as expected. PC 2 and 3 were far more interesting in that four distinct clusters of covarying miRNAs were identified as shown in Fig. 6A.

Figure 6. Computational modeling of covariant miRNAs using the cue-signal-response paradigm.

(A) Principle component (PC) modeling revealed four unique miRNA clusters that associate with either normoxia/hypoxia or other biological function. Labeled miRs are the key miRs verified by RT-PCR. (B) Scores plot (left) and Loadings plot (right) from PLSR analysis trained with 3 or 12 hr normoxia or hypoxia treatment with only the 11 miRs of interest, matched to responses of tube formation, and mRNA expression of CTGF, COL I, COLIII, and vimentin. CTGF and tube formation responses are clearly segregated over PC 2 (oxygen treatment) and covariance of hypoxia with tube formation and normoxia with CTGF were observed. Covarying miRs are plotted as well in PC space. (C) Goodness of prediction for responses of tube formation, and mRNA expression of CTGF, COL I, COL III, and vimentin was tested on the models to compare reduced models of 11 select miR and 211 top VIP miRs to the full model of all 377 miR. The refined models retained high R2 values.

To assign biological activity to each of these clusters, we used the miRNAs from the microarray that were validated by qRT-PCR (Fig. 6A) as landmarks on the principle component plot. miR-20a, miR-199a-5p, and miR-292-5p covary with the green cluster, miR- 292-3p with the blue cluster, and miR-17, miR-103 with the red cluster, and miR-17, miR-210, miR-15b, miR-20a cluster with responses that are a combination of both the red and blue clusters.

Partial least square regression linked miR clusters to physiological responses

Partial least squares regression (PLSR) was used to establish a relationship between the cue (preconditioning hypoxia/normoxia and time duration) and the signal (miRNA levels), which were then mapped onto a putative biological response in an unbiased approach (cue-signal-response paradigm). PLSR models were made using the entire 377 miRs from the microarray matched to the responses of tube formation, and mRNA expression of CTGF, COL1, COL3, and vimentin as measured above, but then a reduced model was made with just the 11 miRNAs confirmed by microRNA array that were matched to physiologically relevant outcomes for angiogenesis and fibrosis. Scores plot shows that each treatment is separated across a principle component (PC) with each time/treatment combination in a different quadrant (Fig. 6B). Separation across PC 1 (x-axis) indicates time difference as 3 hr and 12 hr timepoints are on opposite sides, and PC 2 (y-axis) separates the cues by oxygen treatment. In the loadings plot to the right in Fig. 6B, CTGF and tube formation responses were segregated over PC 2 (oxygen treatment). Covarying miRs are shown as well on the loadings plot in PC space.

Refined PLSR models retained integrity

Predictability of our model using a bootstrapping approach was determined for responses of tube formation, and mRNA expression of CTGF, COL1, COL3, and vimentin. PLSR also determines the most important miRNA signals contributing to that response by calculating the variable importance for projection (VIP). The 211 miRNAs with VIP values greater than or equal to 1 were chosen in an unbiased manner, and their model’s predictability was compared to the full model of all 377 miRNAs and against the 11 select miRNA model. The model trained only with significant VIPs had the best predictability of 99%. However, the model with only the 11 miRNAs still maintained a 96.8% predictability (Fig. 6C), slightly above the 96.5% of the full set of 377 miRNAs. This finding indicates that these 11 miRNAs may provide sufficient data to predict a biological response after exosome treatment or even that manipulating their relative levels may be sufficient to drive that particular biological response of CTGF expression or tube formation.

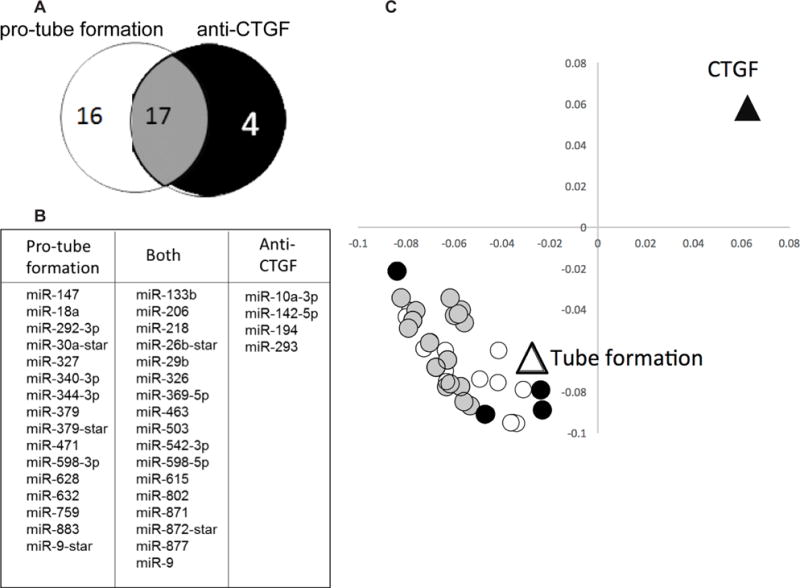

Unbiased identification of additional miRNAs that significantly contribute to angiogenic and antifibrotic responses but not identified by microarray

To identify other miRNAs that may contribute to these responses, beyond the initial 11 chosen based on fold-change in the microarray, miRNA weighted coefficients of significant magnitude were investigated for being towards or against the physiological responses of CTGF and tube formation. Of these, 33 unique miRNAs were pro-tube formation (positive weighted coefficient) and 21 were anti-CTGF (negative weighted coefficient) with 17 miRNAs fitting this category for both responses (Fig 7A). The list is shown in Fig. 7B. Plotting only these miRNAs in principle component space illustrates clustering with angiogenic response of tube formation, and are anti-fibrotic in that they are opposite CTGF mRNA expression (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7. PLSR analysis identifies additional miRNAs from exosomes that covary with angiogenic (tube formation) and anti-fibrotic (anti-CTGF) responses.

Weighted coefficients of miRNAs determined to have significant VIP values were investigated for their projections towards or against responses of CTGF and tube formation to identify other miRs beyond the initial 11 chosen based on fold change in the microarray. (A) Venn diagram indicating that 33 unique miRs were pro-tube formation and 21 miRs were anti-CTGF, with 17 miRs projecting towards both responses. (B) List of miRs associating with only pro-tube formation, against CTGF, or both responses. (C) Loadings plot of these 37 miRs with responses, showing weighted coefficients and clustering of miRs identified through unbiased PLSR analysis.

Hypoxic exosomes improve function in the infarcted heart

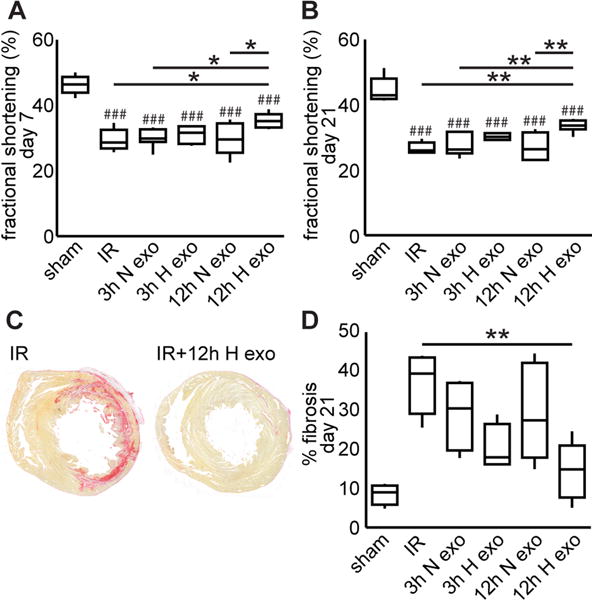

We measured fractional shortening (FS) of the left ventricle 7 and 21 days following ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury (Fig. 8A and B). IR significantly reduced function at both time points, but only treatment with 12h exosomes significantly improved function: in the acute phase (increased from 30.6% to 36.4%) and chronic phase (increased from 27.6% to 34.2%). We also measured fibrosis in reconstructed whole heart sections. Only treatment with 12h exosomes significantly reduced fibrosis (Fig. 8C–E).

Figure 8. Exosomes generated in hypoxia for 12h improved the infarcted heart.

In a rat model of ischemia-reperfusion, fractional shortening of the left ventricle significantly decreased 7 days (A) and 21 days (B) post-surgery. The only treatment that improved fractional shortening was 12h hypoxic exosomes. Sections were stained with picrosirius red and whole heart sections were reconstructed for fibrosis quantification (C and D). Only treatment with 12h hypoxic exosomes significantly reduced fibrosis (E). Mean±SEM, n=4–7, ANOVA followed by Tukey post-test. ###p<0.001 compared to sham group, *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

DISCUSSION

Stem cell-based therapies to treat detrimental myocardial remodeling and cardiac dysfunction post-MI have shown promise, but significant obstacles to this approach remain. If possible, the amplification and delivery of beneficial paracrine signals generated by these cells could overcome obstacles associated with cell injection-based approaches to repair damaged myocardium10, 27. Since CPCs are specialized to function in the heart, CPC-generated signals may be particularly well suited to treat cardiac pathologies. Very few studies have investigated the therapeutic potential of CPC exosomes. In one, exosomes enhanced endothelial migration, indicating angiogenic effects25. CPC exosomes were also shown to reduce myoblast apoptosis in vitro and decrease myocyte cell death in an animal MI model23. However, in both of these studies, exosomes were generated under normoxic conditions, which likely did not reflect the state of post-infarct tissue. Importantly, hypoxic preconditioning enhanced the benefit of CPC therapy in an animal MI model28. Here, exosomes generated by CPCs grown under normoxic conditions had a diminished reparative capacity compared to exosomes from hypoxic cells. This difference in physiologic response was not due to vesicle size, total RNA content or protein levels, since these values were similar between the different exosome groups. We found punctate (~1 μm) fluorescence in recipient cells treated by the different groups of exosomes, suggesting that exosomes deposit their cargo through endocytic pathways, which is then transported to the perinuclear region by the cytoskeleton10, 20.

We found that hypoxic exosomes induced tube formation, but the effect leveled off after 0.1 μg/mL. Disruption of exosomes by means of sonication abrogated the effect of hypoxic exosomes on tube formation, indicating the need for intact exosomes for induction of the physiologic effect. Furthermore, RISC inhibition attenuated the angiogenic effects of hypoxic exosomes, strongly suggesting that exosomal miRNAs were responsible for changes the physiological effects. Importantly, hypoxia increased the levels of pro-angiogenic miR-1729 and -21030, 31 in exosomes. We were unable to detect any major changes in a panel of angiogenic genes studied following treatment with exosomes from hypoxic (12h) CPCs. While there were some changes in other groups, these were small (<1.4-fold) and did not lead to increased tube formation. It could be possible that exosome treatment alters other processes involved in angiogenesis such as endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and/or survival.

Post-MI, the proliferation of fibroblasts leads to the formation of non-contractile scar tissue32, which, when combined with the extensive cardiomyocyte death10, leads to long-term systolic dysfunction. In the damaged heart, fibroblasts are stimulated by cytokines such as TGF-β, which leads to an increase in production of CTGF33, exacerbation of extracellular matrix production34, and enhanced fibrosis35. We found that exosomes from hypoxic CPCs decreased levels of CTGF, Vimentin, and Collagens I and III, while there was no effect of exosomes from normoxic CPCs. The beneficial effects of hypoxia-derived CPC exosomes could be due to the increased levels of miR-1736, -199a37, -21031, and -29237, all of which have been either demonstrated to target or predicted to target genes involved in the fibrosis pathway. Specifically, miR-17 has been shown to regulate CTGF levels36, 38. We did examine cardiomyocytes in this study, but no functional benefit was seen after treatment with any exosome group (Supplemental Fig. V).

We used microarray analysis to examine temporally dynamic extracellular miRNA release from CPCs following 3 and 12 hr of hypoxia. Of the 11 miRNAs upregulated by at least 2-fold by hypoxia at the 12-hr time point, qRT-PCR confirmed that seven were encapsulated by exosomes. Interestingly, most of these have been shown to be involved in regulating cardiac functions of interest. One of the hypoxia-generated miRNAs, miR-15b, has been shown to be upregulated in the circulation of patients with critical limb ischemia39. Here, we focused on miRNAs encapsulated within exosomes, although miRNAs may be transported extracellularly by other modalities, namely microparticles, proteins, and lipoproteins, which were not evaluated in this study8, 12, 14, 15. Indeed, we did detect 2 miRNAs upregulated in microparticles and these also may have beneficial effects. Additionally, exosomes carry other molecules including proteins, phospholipids, and carbohydrates. While our data suggest exosomal miRNA played a critical role in the physiologic response of recipient cells, we do not rule out the contribution of other exosomal cargo.

Computational modeling tools have been instrumental in evaluating large biological datasets, so they were well-suited to handle our wide array of dynamic exosomal content. We measured 377 mature miRNAs at both the 3- and 12-hr time points that may be difficult to attribute to specific functions. The cue-signal-response paradigm was able to extract important biological information by integrating known and unknown measurable variables. This powerful computational tool has been used to better understand datasets and develop predictive models in a variety of biological systems40, 41. The use of this paradigm was particularly important for miRNAs since one miRNA may impact hundreds of genes. miRNAs that changed covariantly will result in them clustering through principle component analysis. Indeed, PCA on the normalized data from our microarray analysis identified miRNAs clusters that covary based on treatment condition. We were surprised to find that the majority of miRNAs clearly grouped into four major clusters. The black cluster is pro-hypoxic and blue is the opposite. Red and green clusters do not respond to hypoxia (zero projection onto PC2, the hypoxia axis), but are the effects due to another currently unknown mechanism.

In the PLSR model trained with only with the 11 miRNAs from the array, miR-292 had a high VIP scoring, indicating a potentially influential role in the responses. To date there are no reports of miR-292 as a regulator of cardiac function, and studies are underway to determine the role of this miRNA in the cardiovascular system. Since the functions of miR-20a and -17 have been described, other miRNAs closely clustering and covarying with these two may have similar roles in modulating cardiac function and repair. Overall, PLSR modeling is a helpful method to prioritize testing of new miRNAs that may be involved in certain biological outcomes. For example, if further analysis verifies an important role for miR-292 in improving cardiac function, then inclusion of other miRNAs from its cluster could amplify its protective effects. Indeed miR-292 was identified, unbiased, in the new group of miRNAs based on their weighted coefficients (Fig 7B), along with 36 others that might be beneficial to amplify the effect of tube formation while minimizing the pro-fibrotic response. We initially only examined the miRNA that were upregulated >2-fold with RT-PCR, but the model was able to consider all miRNA within the array. There were several pre-miRNA that were also increased, although none over 2-fold. Additionally, we did not examine the miRNA that were decreased in hypoxic exosomes. This is quite difficult to address, as even if the miRNA are decreased in hypoxic-derived exosomes, they will still be transferred (albeit at a smaller level) to recipient cells. They could potentially explain why normoxic exosomes were less effective (a decrease in hypoxic-derived exosomes would mean they are enriched in normoxic-derived exosomes). We saw that exosomes from hypoxic CPCs had decreased levels of miR-320 (shown to be anti-angiogenic)42, 43, miR-222 (pro-apoptotic and anti-migration)44, and miR-185 (pro-fibrotic)45. The lack of these signals in hypoxic-derived exosomes and the enrichment of pro-regenerative miRNA could be an interesting area for future studies, and these types of modeling algorithms can provide information on potential biological impact.

Many of these 37 identified in Fig. 7B were not identified by high fold change in the microarray, providing a greater rationale for employing multivariate analytical methods that consider the miRNA levels changing in response to a cue, but having an effect on a number of biological responses, instead of solely focusing on the miRNA signal changing as the final outcome. By mapping the signal changes to different biological responses (here CTGF, tube formation, collagens I and III, and vimentin mRNA), the projection or contribution of that signal to several responses can be predicted, and their contributions to different aspects of a complex biological response may be parsed or integrated, providing insight into the same decisions cells must make.

Finally, delivery of exosomes derived from CPCs subjected to 12 hr of hypoxia improved both acute and chronic function, while inhibiting fibrosis. These data are in agreement with both our in vitro studies, and our computational model. Recently several papers have demonstrated that exosomes derived from stem cells cultured under normoxic conditions also have beneficial effects post-infarction. While one study used cardiosphere-derived cells46, the other used CPCs similar to this study47. One major difference is that the authors used total extracellular vesicles and not exosomes alone, thus it is unclear whether the other studies would see a benefit from subjecting those cells to hypoxia. What is interesting is that those studies, as well as the one presented here, demonstrate that vesicular transfer of miRNA is likely driving the protective/regenerative process.

In this report, we show that CPCs release a beneficial paracrine signal in response to hypoxia. We confirmed that exosomal miRNAs content is dynamically regulated based on the length of time CPCs are exposed to hypoxia. Based on our data, we developed a computational model to determine how exosome-generating conditions, miRNAs, and physiological responses co-vary. Together, our findings support the development of hypoxic CPC-derived exosomes as naturally derived therapeutics and lay the groundwork for statistical models that direct bio-inspired therapeutics of rational design.

Supplementary Material

Novelty And Significance.

What Is Known?

Stem cell therapy for myocardial infarction (MI) has provided mixed results, with beneficial paracrine signaling being a common explanation.

A small population of cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs) resides in the heart, though the full understanding of these cells’ function has yet to be fully elucidated.

Ultimately, the body is unable to fully repair the heart post-MI, leading to significant long-term ailments.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

CPCs secrete exosomes in response to hypoxic conditions that benefit cardiac cells and reduce deleterious effects in the post-MI heart.

miR-15b, -17, -20a, -103, -199a, -210, and -292 are upregulated in exosomes generated in hypoxic conditions, which contribute to cardiac repair.

Systems biology analysis correlates exosomal microRNA levels to CPC stimulation and physiological responses, which provides impetus and guidance for biologically inspired therapeutics.

CPCs are attractive candidates for treatment, and it is believed that a potential mechanism is paracrine signaling. The therapeutic potential and cargo of exosomes generated in conditions that mimic MI, such as hypoxia, are unknown. We found that CPC exosomes are internalized by cardiac fibroblasts and endothelial cells, and subsequently regulate their function. These exosomes also decreased cardiac fibrosis in a rat MI model and improved cardiac function in the acute and chronic phases. We found seven microRNAs to be upregulated in exosomes generated under hypoxia, and identified clusters of co-varying microRNAs through systems biology analysis. This paper demonstrates that CPCs tailor the contents of secreted exosomes in response to oxygen content toward a regenerative phenotype. This paper is the first to show a beneficial effect of exosomes derived under hypoxic conditions, as well as model the correlation of time and oxygen levels with co-varying microRNAs and physiological responses. These findings suggest that the paracrine effect of CPCs may be enhanced by hypoxia and could be a potential mechanism of cell therapy in vivo. Furthermore, systems biology analysis can be used to determine potential microRNA mediators for future investigation.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This publication has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. HHSN268201000043C to MED and CS, as well as HL12438 to MED, MOP, and CS, and National Science Foundation through Science and Technology Center Emergent Behaviors of Integrated Cellular Systems (EBICS) Grant CBET-0939511 to MOP. The authors wish to acknowledge the Emory Integrated Genomics Core, Emory Integrated Cellular Imaging Microscopy Core, Emory Pediatric Flow Cytometry Core, and the Robert P. Apkarian Integrated Electron Microscopy Core.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

WDG, CDS, MOP, and MED designed the research. WDG, SGC, KMF, JTM, MEB, and MOP performed research. CDS and MOP contributed analytical tools. WDG, MOP, KMF, and MED analyzed data. WDG, SGC, MOP, CDS, and MED wrote the paper.

DISCLOSURES

None.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms: None.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, 3rd, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Pandey DK, Paynter NP, Reeves MJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2014 update: A report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2014;129:e28–e292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assmus B, Schachinger V, Teupe C, Britten M, Lehmann R, Dobert N, Grunwald F, Aicher A, Urbich C, Martin H, Hoelzer D, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Transplantation of progenitor cells and regeneration enhancement in acute myocardial infarction (topcare-ami) Circulation. 2002;106:3009–3017. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000043246.74879.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beltrami AP, Barlucchi L, Torella D, Baker M, Limana F, Chimenti S, Kasahara H, Rota M, Musso E, Urbanek K, Leri A, Kajstura J, Nadal-Ginard B, Anversa P. Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration. Cell. 2003;114:763–776. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00687-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linke A, Muller P, Nurzynska D, Casarsa C, Torella D, Nascimbene A, Castaldo C, Cascapera S, Bohm M, Quaini F, Urbanek K, Leri A, Hintze TH, Kajstura J, Anversa P. Stem cells in the dog heart are self-renewing, clonogenic, and multipotent and regenerate infarcted myocardium, improving cardiac function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8966–8971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502678102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gnecchi M, Zhang Z, Ni A, Dzau VJ. Paracrine mechanisms in adult stem cell signaling and therapy. Circ Res. 2008;103:1204–1219. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li X, Arslan F, Ren Y, Adav SS, Poh KK, Sorokin V, Lee CN, de Kleijn D, Lim SK, Sze SK. Metabolic adaptation to a disruption in oxygen supply during myocardial ischemia and reperfusion is underpinned by temporal and quantitative changes in the cardiac proteome. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:2331–2346. doi: 10.1021/pr201025m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheurer SB, Rybak JN, Rosli C, Neri D, Elia G. Modulation of gene expression by hypoxia in human umbilical cord vein endothelial cells: A transcriptomic and proteomic study. Proteomics. 2004;4:1737–1760. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mittelbrunn M, Sanchez-Madrid F. Intercellular communication: Diverse structures for exchange of genetic information. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio. 2012;13:328–335. doi: 10.1038/nrm3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skog J, Wurdinger T, van Rijn S, Meijer DH, Gainche L, Sena-Esteves M, Curry WT, Jr, Carter BS, Krichevsky AM, Breakefield XO. Glioblastoma microvesicles transport rna and proteins that promote tumour growth and provide diagnostic biomarkers. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1470–1476. doi: 10.1038/ncb1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sahoo S, Losordo DW. Exosomes and cardiac repair after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2014;114:333–344. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuwabara Y, Ono K, Horie T, Nishi H, Nagao K, Kinoshita M, Watanabe S, Baba O, Kojima Y, Shizuta S, Imai M, Tamura T, Kita T, Kimura T. Increased microrna-1 and microrna-133a levels in serum of patients with cardiovascular disease indicate myocardial damage. Circ Cardiovasc Gen. 2011;4:446–454. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.958975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arroyo JD, Chevillet JR, Kroh EM, Ruf IK, Pritchard CC, Gibson DF, Mitchell PS, Bennett CF, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, Stirewalt DL, Tait JF, Tewari M. Argonaute2 complexes carry a population of circulating micrornas independent of vesicles in human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:5003–5008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019055108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kroh EM, Parkin RK, Mitchell PS, Tewari M. Analysis of circulating microrna biomarkers in plasma and serum using quantitative reverse transcription-pcr (qrt-pcr) Methods. 2010;50:298–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vickers KC, Palmisano BT, Shoucri BM, Shamburek RD, Remaley AT. Micrornas are transported in plasma and delivered to recipient cells by high-density lipoproteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:423–U182. doi: 10.1038/ncb2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu H, Fan G-C. Extracellular/circulating micrornas and their potential role in cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;1:138–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mittelbrunn M, Gutierrez-Vazquez C, Villarroya-Beltri C, Gonzalez S, Sanchez-Cabo F, Gonzalez MA, Bernad A, Sanchez-Madrid F. Unidirectional transfer of microrna-loaded exosomes from t cells to antigen-presenting cells. Nat Comm. 2011;2:282. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fichtlscherer S, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Circulating micrornas: Biomarkers or mediators of cardiovascular diseases? Arterioscl Throm Vas. 2011;31:2383–2390. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.226696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohshima K, Inoue K, Fujiwara A, Hatakeyama K, Kanto K, Watanabe Y, Muramatsu K, Fukuda Y, Ogura S, Yamaguchi K, Mochizuki T. Let-7 microrna family is selectively secreted into the extracellular environment via exosomes in a metastatic gastric cancer cell line. PLoS ONE. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muller G, Jung C, Straub J, Wied S, Kramer W. Induced release of membrane vesicles from rat adipocytes containing glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored microdomain and lipid droplet signalling proteins. Cell Signal. 2009;21:324–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barile L, Gherghiceanu M, Popescu LM, Moccetti T, Vassalli G. Ultrastructural evidence of exosome secretion by progenitor cells in adult mouse myocardium and adult human cardiospheres. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:354605. doi: 10.1155/2012/354605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park JE, Tan HS, Datta A, Lai RC, Zhang H, Meng W, Lim SK, Sze SK. Hypoxic tumor cell modulates its microenvironment to enhance angiogenic and metastatic potential by secretion of proteins and exosomes. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:1085–1099. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900381-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fruhbeis C, Frohlich D, Kramer-Albers EM. Emerging roles of exosomes in neuron-glia communication. Front Physiol. 2012;3:119. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen L, Wang Y, Pan Y, Zhang L, Shen C, Qin G, Ashraf M, Weintraub N, Ma G, Tang Y. Cardiac progenitor-derived exosomes protect ischemic myocardium from acute ischemia/reperfusion injury. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2013;431:566–571. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sahoo S, Klychko E, Thorne T, Misener S, Schultz KM, Millay M, Ito A, Liu T, Kamide C, Agrawal H, Perlman H, Qin G, Kishore R, Losordo DW. Exosomes from human cd34(+) stem cells mediate their proangiogenic paracrine activity. Circ Res. 2011;109:724–728. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.253286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vrijsen KR, Sluijter JP, Schuchardt MW, van Balkom BW, Noort WA, Chamuleau SA, Doevendans PA. Cardiomyocyte progenitor cell-derived exosomes stimulate migration of endothelial cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:1064–1070. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan GS, Chiu CH, Garchow BG, Metzler D, Diamond SL, Kiriakidou M. Small molecule inhibition of risc loading. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7:403–410. doi: 10.1021/cb200253h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urbich C, Aicher A, Heeschen C, Dernbach E, Hofmann WK, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Soluble factors released by endothelial progenitor cells promote migration of endothelial cells and cardiac resident progenitor cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;39:733–742. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang YL, Zhu W, Cheng M, Chen L, Zhang J, Sun T, Kishore R, Phillips MI, Losordo DW, Qin G. Hypoxic preconditioning enhances the benefit of cardiac progenitor cell therapy for treatment of myocardial infarction by inducing cxcr4 expression. Circ Res. 2009;104:1209–1216. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.197723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mendell JT. Miriad roles for the mir-17-92 cluster in development and disease. Cell. 2008;133:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu H, Fan GC. Role of micrornas in the reperfused myocardium towards post-infarct remodelling. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;94:284–292. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu S, Huang M, Li Z, Jia F, Ghosh Z, Lijkwan MA, Fasanaro P, Sun N, Wang X, Martelli F, Robbins RC, Wu JC. Microrna-210 as a novel therapy for treatment of ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 2010;122:S124–131. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.928424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hill JA, Olson EN. Cardiac plasticity. New Engl J Med. 2008;358:1370–1380. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leask A, Abraham DJ. Tgf-beta signaling and the fibrotic response. FASEB J. 2004;18:816–827. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1273rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brigstock DR. Connective tissue growth factor (ccn2, ctgf) and organ fibrosis: Lessons from transgenic animals. J Cell Comm Signal. 2010;4:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s12079-009-0071-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu S, Shi-wen X, Abraham DJ, Leask A. Ccn2 is required for bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis in mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:239–246. doi: 10.1002/art.30074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kodama T, Takehara T, Hikita H, Shimizu S, Shigekawa M, Tsunematsu H, Li W, Miyagi T, Hosui A, Tatsumi T, Ishida H, Kanto T, Hiramatsu N, Kubota S, Takigawa M, Tomimaru Y, Tomokuni A, Nagano H, Doki Y, Mori M, Hayashi N. Increases in p53 expression induce ctgf synthesis by mouse and human hepatocytes and result in liver fibrosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3343–3356. doi: 10.1172/JCI44957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Betel D, Wilson M, Gabow A, Marks DS, Sander C. The microrna.Org resource: Targets and expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D149–153. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ernst A, Campos B, Meier J, Devens F, Liesenberg F, Wolter M, Reifenberger G, Herold-Mende C, Lichter P, Radlwimmer B. De-repression of ctgf via the mir-17-92 cluster upon differentiation of human glioblastoma spheroid cultures. Oncogene. 2010;29:3411–3422. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spinetti G, Fortunato O, Caporali A, Shantikumar S, Marchetti M, Meloni M, Descamps B, Floris I, Sangalli E, Vono R, Faglia E, Specchia C, Pintus G, Madeddu P, Emanueli C. Microrna-15a and microrna-16 impair human circulating proangiogenic cell functions and are increased in the proangiogenic cells and serum of patients with critical limb ischemia. Circ Res. 2013;112:335–346. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park KY, Li WA, Platt MO. Patient specific proteolytic activity of monocyte-derived macrophages and osteoclasts predicted with temporal kinase activation states during differentiation. Integr Biol. 2012;4:1459–1469. doi: 10.1039/c2ib20197f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Platt MO, Wilder CL, Wells A, Griffith LG, Lauffenburger DA. Multipathway kinase signatures of multipotent stromal cells are predictive for osteogenic differentiation: Tissue-specific stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2804–2814. doi: 10.1002/stem.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ren XP, Wu J, Wang X, Sartor MA, Qian J, Jones K, Nicolaou P, Pritchard TJ, Fan GC. Microrna-320 is involved in the regulation of cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury by targeting heat-shock protein 20. Circulation. 2009;119:2357–2366. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.814145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang XH, Qian RZ, Zhang W, Chen SF, Jin HM, Hu RM. Microrna-320 expression in myocardial microvascular endothelial cells and its relationship with insulin-like growth factor-1 in type 2 diabetic rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2009;36:181–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2008.05057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu X, Cheng Y, Yang J, Xu L, Zhang C. Cell-specific effects of mir-221/222 in vessels: Molecular mechanism and therapeutic application. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oak SR, Murray L, Herath A, Sleeman M, Anderson I, Joshi AD, Coelho AL, Flaherty KR, Toews GB, Knight D, Martinez FJ, Hogaboam CM. A micro rna processing defect in rapidly progressing idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e21253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ibrahim AG, Cheng K, Marban E. Exosomes as critical agents of cardiac regeneration triggered by cell therapy. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;2:606–619. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barile L, Lionetti V, Cervio E, Matteucci M, Gherghiceanu M, Popescu LM, Torre T, Siclari F, Moccetti T, Vassalli G. Extracellular vesicles from human cardiac progenitor cells inhibit cardiomyocyte apoptosis and improve cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;103:530–541. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Geladi P, Kowalski BR. Partial least-squares regression – a tutorial. Analytica Chimica Acta. 1986;185:1–17. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.