Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Average nightly sleep times precipitously decline from childhood through adolescence. There is increasing concern that historical shifts also occur in overall adolescent sleep time.

METHODS:

Data were drawn from Monitoring the Future, a yearly, nationally representative cross-sectional survey of adolescents in the United States from 1991 to 2012 (N = 272 077) representing birth cohorts from 1973 to 2000. Adolescents were asked how often they get ≥7 hours of sleep and how often they get less sleep than they should. Age-period-cohort models were estimated.

RESULTS:

Adolescent sleep generally declined over 20 years; the largest change occurred between 1991–1995 and 1996–2000. Age-period-cohort analyses indicate adolescent sleep is best described across demographic subgroups by an age effect, with sleep decreasing across adolescence, and a period effect, indicating that sleep is consistently decreasing, especially in the late 1990s and early 2000s. There was also a cohort effect among some subgroups, including male subjects, white subjects, and those in urban areas, with the earliest cohorts obtaining more sleep. Girls were less likely to report getting ≥7 hours of sleep compared with boys, as were racial/ethnic minorities, students living in urban areas, and those of low socioeconomic status (SES). However, racial/ethnic minorities and adolescents of low SES were more likely to self-report adequate sleep, compared with white subjects and those of higher SES.

CONCLUSIONS:

Declines in self-reported adolescent sleep across the last 20 years are concerning. Mismatch between perceptions of adequate sleep and actual reported sleep times for racial/ethnic minorities and adolescents of low SES are additionally concerning and suggest that health education and literacy approaches may be warranted.

Keywords: adolescence, age-period-cohort, Monitoring the Future, sleep

What's Known on This Subject:

Adequate sleep is critical for adolescent health. Available data suggest a historical downward trend in sleep behavior, but there has been no rigorous evaluation of recent US trends.

What This Study Adds:

The proportion of adolescents who regularly obtain ≥7 hours of sleep is decreasing. Decreases in sleep exhibit period effects that are constant across adolescents according to gender, race, socioeconomic factors, and urbanicity. The gender gap in adequate sleep is widening.

Inadequately short or long sleep times are associated with a wide range of adverse outcomes in adolescence, including problems in school performance,1 mental health,2 reckless behavior,3 substance use, and weight gain.4 Risk factors for inadequate sleep include older adolescent age,5,6 negative affect and social inhibition,7 sedentary behavior,2,8 and low socioeconomic status (SES).4

Adolescence is a particularly vulnerable developmental period for the emergence of inadequate sleep patterns. Population-based estimates indicate that approximately one-fourth to one-third of adolescents get inadequate nightly sleep,2 and there is rising concern in the scientific literature (as well as the lay media) that these estimates are increasing.9–11 Although the underlying reasons for this potential increase are unknown, there has been speculation regarding the effects of increased Internet and social media use and pressures due to the heightened competitiveness of the college admissions process.11–13 Empirical data on such factors are scarce, however.9,14

Given that the evidence is consistent in showing that sleep patterns change across adolescence (an age effect), a critical aspect of sleep trends is whether changing patterns of sleep are also indicative of period or cohort effects.15 Period effects refer to variance over time that is common across all age groups; for example, implementation of population-wide screening for a specific health outcome may uncover cases across all age groups or recent increases in marijuana use across age.16 Cohort effects, by contrast, refer to variance over time that is specific to individuals born in or around certain years; for example, vaccination of young children would affect disease risk for those cohorts who are vaccinated as they move through the life course, and economic shocks such as the Great Depression influence specific cohorts as they emerge into adulthood.17 A period effect in sleep duration would imply that factors which are common across adolescents in all age groups (eg, increasing screen time with mobile technology) may be fruitful factors to explore as potential mechanisms and targets for intervention. A cohort effect in sleep duration would imply that factors which are becoming increasingly common for recent cohorts as children enter into adolescence (eg, increased psychological distress,18 increased nonmedical use of prescription medication19) underlie trends over time, and that efforts to improve sleep should focus on these increasing factors before adolescence begins.

The present study provides, to the best of our knowledge, the first systematic analysis of age, period, and cohort effects in adolescent sleep patterns, harnessing nationally representative data covering >270 000 eighth, 10th, and 12th grade students in the United States with consistently measured questions on sleep duration and sleep problems for the past 2 decades.

Methods

Sample

Monitoring the Future includes an annually conducted cross-sectional national survey; eighth, 10th, and 12th grade students in ∼130 US public and private high schools in the United States have been sampled annually since 1991. Included measurement years were 1991 through 2012, representing birth cohorts 1973 through 2000. High schools are selected by using a multistage random sampling design with replacement. Schools are invited to participate for 2 years. Schools that decline participation are replaced with schools that are similar in terms of geographic location, size, and urbanicity. The overall school participation rates (including replacements) range from 95% to 99% for all study years. Student response rates have averaged 83%, with no systematic trend; they range from 77% (1976) to 91% (1996, 2001, and 2006). Almost all nonresponse is due to absenteeism; <1% of students refuse to participate. Self-administered questionnaires are given to students. Detailed descriptions of the design and procedures are provided elsewhere.16

The present study focused on students who were randomized to receive a questionnaire that included questions regarding sleep. The sample was restricted to those in the 3 modal ages of each grade to prevent loss of confidentiality (∼95% of the total possible sample). The total eligible sample size was 272 077 (44 892 eighth-graders, 114 256 10th-graders, and 112 929 12th-graders). Respondents with missing data on sleep questions were not analyzed.

Measures

Sleep Duration and Disturbance

Two questions captured sleep patterns among respondents. Question wording and response options were constant across time and across grade. First, respondents were asked, “How often do you … get at least 7 hours of sleep?” Responses were arranged on a 6-point scale from “never” (average 3.86% across survey year and grade) to “every day” (average 28.37% across survey year and grade). Adolescents reporting ≥7 hours of sleep every day or almost every day were considered to regularly sleep ≥7 hours per day, versus those reporting sometimes, seldom, or never sleeping ≥7 hours per day.

Second, respondents were asked, “How often do you … get less sleep than you should?” Responses were arranged on a 6-point scale from “never” (average 13.93% across survey year and grade) to “every day” (average 17.96% across survey year and grade). Adolescents reporting getting less sleep than they should never or seldom were considered to regularly obtain adequate sleep, versus those reporting every day, almost every day, or sometimes. These 2 sleep items were correlated at 0.31 (P < .0001) across survey years.

Demographic Characteristics

Analyses were stratified according to respondent-identified gender (male: 49%), race (non-Hispanic white: 63%; non-Hispanic black: 13%; Hispanic: 12%; Asian: 4%; other: 8%). Furthermore, responses were stratified according to parental SES, measured as the highest level of education of either the mother or the father, as reported by the adolescent (less than high school [10%], high school [25%], or more than high school [65%]). Finally, analyses were stratified according to urbanicity (urban: 81%), which was based on residence in metropolitan statistical areas.

Statistical Analysis

We descriptively graphed the data by age and time period and then estimated age-period-cohort effect models. Estimating age, period, and cohort effects is complicated by the linear dependency among the 3 variables (cohort = period – age). The Clayton and Shifflers model20,21 was used for these analyses. The model iteratively estimates parameters for age, period, and cohort effects and selects among them by using model fit statistics, including the Akaike information criterion and the Bayesian information criterion, likelihood-based deviance statistics, and penalizing additional degrees of freedom. An age parameter was fit first, based on the previous literature.22 The overall linear change (termed “drift”) that is a sum of both period and cohort effects but, because of the linear dependency of period and cohort, not able to be uniquely attributed to either, was estimated next. Finally, unique coefficients for period and cohort effects (termed “curvatures”) were obtained. We chose birth year 1980 as the cohort referent group because it was in the midpoint of the cohort distributions; 1995 was chosen as the period referent group because it contained data on a high number of birth cohorts. Modeling was conducted by using the “apc.fit” function in the “Epi” package of R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Sensitivity analyses were conducted, with sleep variables as continuous outcomes, by using the Intrinsic Estimator algorithm implemented in Stata (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).23 Sensitivity analyses using alternative models with different underlying model assumptions in the age-period-cohort analysis provide a rigorous robustness check on the results.15

Finally, the data were subset into 5-year time periods, except the most recent time period, which was concatenated into a 2-year window. We examined the association between demographic variables with the 2 sleep outcomes, and tested interactions between demographic characteristics and year, modeling year as a continuous variable to observe systematic trends over time.

Results

Trends in Sleep by Age and Time Period From 1991 to 2012

Figure 1 shows the percentage of students reporting regular ≥7 hours of sleep per night and the percentage of students reporting regularly getting adequate sleep, according to age and time period. Sleep consistently decreased across age, in all time periods, except for 19-year-olds, among whom there was more variation. It is noteworthy that the 19-year-olds in the present study were attending high school and thus not necessarily representative of 19-year-olds in general. Sleep decreased across time as well, with the largest decrease from 1991–1995 to 1996–2000. The largest decrease was observed for 15-year-olds, from 71.5% in 1991 to 63.0% in 2012.

FIGURE 1.

According to age and time period, percentage of adolescents who regularly report: A, ≥7 hours of sleep per night; and B, getting adequate sleep per night. The proportion of adolescents who regularly got ≥7 hours of sleep was defined as those who responded that the frequency with which they obtain ≥7 hours of sleep was every day or almost every day versus sometimes, rarely, or never. The proportion of adolescents who regularly get adequate sleep was defined as those who reported that they get less sleep than they should never or seldom versus sometimes, every day, or almost every day.

Age, Period, and Cohort Effects in Adolescent Sleep Patterns From 1991 to 2012

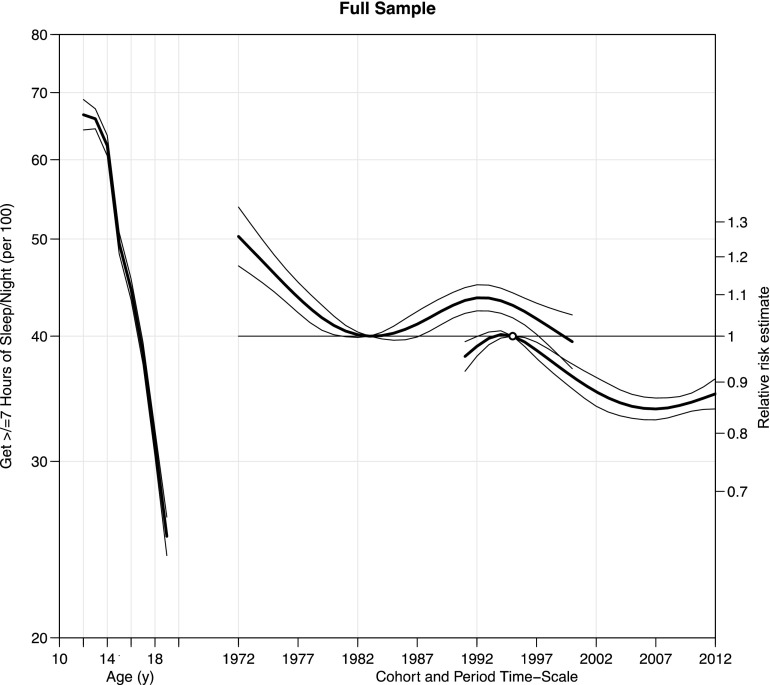

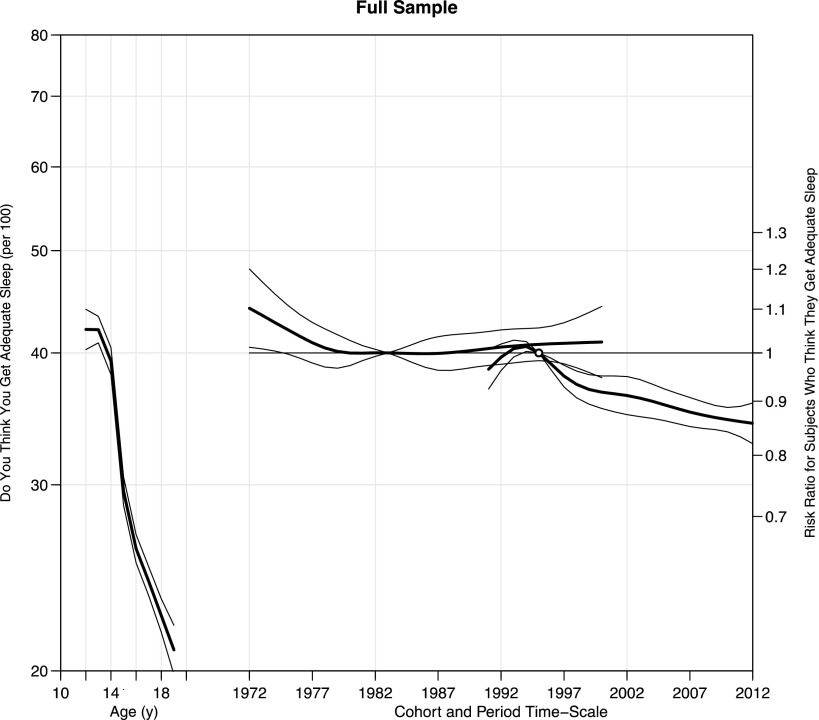

For both sleep outcomes, there was a significant improvement in model fit when period and cohort were added as a parameter (Table 1). Results of the fitted age-period-cohort model for the full sample are shown in Fig 2 for ≥7 hours of sleep and in Fig 3 for regular adequate sleep. As expected, the age-specific probability of regular ≥7 hours of sleep generally decreased across age. Compared with the referent period of 1995, there were significant decreases from 1996 through 2012 in the probability of receiving ≥7 hours of sleep regularly, with those measured in 2007 having the lowest probability of receiving ≥7 hours of sleep compared with 1995. Similar results were observed in Fig 3 for adequate sleep. According to each cohort, the results indicate that there was a significant increase in ≥7 hours of sleep for those cohorts born in the early 1990s (Fig 2); few trends were apparent in cohort effects for adequate sleep per night (Fig 3).

TABLE 1.

Model Fit Statistics for Age-Period-Cohort Model of Adolescent Sleep in the United States

| Model Parameter | Change in Deviance (Degrees of Freedom) | |

|---|---|---|

| ≥7 Hours of Sleep/Night | Adequate Sleep | |

| Age | – | – |

| Age-drift | 411.5 (1)a | 219.53 (1)a |

| Age-cohort | 123.7 (4)a | 14.29 (4)a |

| Age-period-cohort | 37.2 (4)a | 17.22 (4)a |

| Age-period | −54.1 (–4)a | −5.29 (–4) |

| Age-drift | −106.7 (–4)a | −26.23 (–4)a |

Fit statistics are based on an iterative model building strategy, beginning with an age effect and then testing whether the model is significantly improved in fit when drift is added as a parameter, then cohort, then age, period, and cohort. Parameters are then removed from the full age-period-cohort parameterization to determine whether the model fit significantly decreases. The values in the table represent the change in deviance; significant positive parameters indicate that the model has significantly improved, and significant negative parameters indicate that the model has significantly worsened.

FIGURE 2.

Age, period, and cohort effects on the probability that US adolescents regularly report ≥7 hours of sleep per night from 1991 to 2012 in nationally representative samples (N = 270 899). The cohort and period time–scale contains risk ratio estimates for the effect of cohort (far left line) and period (far right line). Thin lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. The cohort estimates were compared with a referent cohort of 1980; thus, the lines can be interpreted as the average proportion of adolescents obtaining ≥7 hours of sleep regularly, regardless of time period, compared with the average proportion in 1980. The period estimates were compared with a referent period of 1995; thus, the lines can be interpreted as the average proportion of adolescents obtaining ≥7 hours of sleep regularly in that year, regardless of cohort, compared with the average proportion in 1995.

FIGURE 3.

Age, period, and cohort effects on the probability that US adolescents regularly report adequate sleep per night from 1991 to 2012 in nationally representative samples (N = 270 719). The cohort and period time–scale contains risk ratio estimates for the effect of cohort (far left line) and period (far right line). Thin lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. The cohort estimates were compared with a referent cohort of 1980; thus, the lines can be interpreted as the average proportion of adolescents obtaining adequate sleep regularly, regardless of time period, compared with the average proportion in 1980. The period estimates were compared with a referent period of 1995; thus, the lines can be interpreted as the average proportion of adolescents obtaining adequate sleep regularly in that year, regardless of cohort, compared with the average proportion in 1995.

Sensitivity Analyses: Age-Period-Cohort Models by Gender, Race, Urbanicity, and SES

In a series of sensitivity analyses, we examined these models by gender, race, urbanicity, and SES and present the results in Supplemental Figs 4 through 7. The results were consistent within each subgroup examined and consistent with what was found for the total sample. There was consistent evidence of a period effect whereby sleep was decreasing regardless of age in more recent years for all subgroups, and some evidence of a positive cohort effect (ie, increase) for those born in the early 1990s, but only for self-perceived adequate sleep and only in some subgroups.

In Supplemental Tables 3 through 6, we examined model fit by demographic characteristics (for race, white and black adolescents were analyzed because we did not have sufficient sample size for other race/ethnic groups). Results were generally consistent in these subgroups, although there was inconsistent evidence for a significant cohort effect for adequate sleep among female subjects, black subjects, and those in nonurban areas. For every subgroup, however, there were significant age and period effects. This finding indicates that age and period were both significantly contributing to the underlying trends over time in adolescent sleep for every subgroup, whereas there was inconsistent evidence for a contribution of birth cohort once age and period are accounted.

Sensitivity Analyses: Age-Period-Cohort Models Using Continuous Sleep Outcomes and the Intrinsic Estimator

An alternative age-period-cohort model was used to examine the robustness of our results using sleep outcomes as continuous variables. Results are shown in Supplemental Fig 8 (getting ≥7 hours of sleep) and Supplemental Fig 9 (getting adequate sleep) and are consistent with the results shown in Figs 1 and 2, respectively, with a strong declining period effect beginning in the late 1990s.

Demographic Associations With Sleep Across Time

Because the age-period-cohort analysis indicated that trends over time in adolescent sleep were primarily a period effect, the data were stratified into time bands (Table 2). Girls were less likely to report regular ≥7 hours of sleep compared with boys in all time periods, with odds ratios ranging from 0.66 in 2011–2012 to 0.68 in 1991–1995 and 1996–2000. All racial/ethnic groups were less likely to report regular ≥7 hours of sleep compared with white subjects, except for black subjects compared with white subjects in 2001–2005 (odds ratio: 1.07 [95% confidence interval: 1.02–1.12]). Nonurban students were more likely to report ≥7 hours of sleep compared with urban students, in all time frames. Compared with those in the lowest SES strata, adolescents in the middle and higher SES strata were more likely to report regular ≥7 hours of sleep, with the strongest associations for adolescents whose parents received a high school education but not more. Finally, 18- to 19-year-olds were the least likely to report regular ≥7 hours of sleep.

TABLE 2.

ORs (95% CIs) for the Association Between Demographic Variables and Probability of Regular ≥7 Hours of Sleep Per Night and Regularly Getting Adequate Sleep, By Time Period

| 1991–1995 | 1996–2000 | 2001–2005 | 2006–2010 | 2011–2012 | Interactions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Get 7 h of sleep | |||||||

| n = | n = 78 444 | n = 57 735 | n = 55 484 | n = 56 646 | n = 22 590 | ||

| Gender | Female | 0.68 (0.66–0.7) | 0.68 (0.66–0.71) | 0.7 (0.67–0.72) | 0.67 (0.64–0.69) | 0.66 (0.63–0.7) | 0.84 |

| Male | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Race | Black | 0.99 (0.95–1.04) | 0.97 (0.92–1.02) | 1.07 (1.01–1.12) | 0.84 (0.79–0.88) | 0.89 (0.81–0.97) | 0.05 |

| Hispanic | 0.9 (0.85–0.94) | 0.99 (0.93–1.04) | 0.95 (0.9–1) | 0.87 (0.83–0.91) | 0.92 (0.85–0.99) | 0.90 | |

| Asian | 0.86 (0.79–0.93) | 0.83 (0.76–0.9) | 0.79 (0.73–0.87) | 0.75 (0.69–0.81) | 0.99 (0.87–1.12) | 0.33 | |

| Other | 1.03 (0.98–1.09) | 1.06 (0.99–1.13) | 1.05 (0.98–1.12) | 0.83 (0.78–0.88) | 0.94 (0.86–1.02) | 0.99 | |

| White | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Urbanicity | Nonurban | 1.12 (1.09–1.16) | 1.11 (1.07–1.16) | 1.06 (1.01–1.1) | 1.11 (1.06–1.15) | 1.15 (1.08–1.22) | 0.93 |

| Urban | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Highest parental education | >High school | 1.33 (1.26–1.41) | 1.25 (1.17–1.34) | 1.22 (1.14–1.32) | 1.34 (1.25–1.44) | 1.34 (1.2–1.5) | 0.10 |

| High school | 1.22 (1.15–1.3) | 1.2 (1.11–1.29) | 1.07 (0.99–1.16) | 1.15 (1.07–1.25) | 1.15 (1.01–1.31) | 0.02 | |

| <High school | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Age, y | 18–19 | 0.29 (0.27–0.31) | 0.27 (0.25–0.29) | 0.25 (0.23–0.27) | 0.29 (0.27–0.32) | 0.32 (0.28–0.35) | <0.01 |

| 16–17 | 0.46 (0.44–0.48) | 0.42 (0.4–0.44) | 0.39 (0.38–0.42) | 0.45 (0.42–0.47) | 0.43 (0.39–0.46) | 0.09 | |

| 14–15 | 0.7 (0.67–0.73) | 0.7 (0.66–0.73) | 0.67 (0.64–0.71) | 0.69 (0.66–0.73) | 0.65 (0.6–0.7) | 0.01 | |

| 12–13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Get adequate sleep | |||||||

| n = 78 374 | n = 57 688 | n = 55 450 | n = 56 617 | n = 22 590 | |||

| Gender | Female | 0.81 (0.78–0.83) | 0.81 (0.79–0.84) | 0.87 (0.83–0.9) | 0.82 (0.79–0.85) | 0.82 (0.77–0.87) | 0.18 |

| Male | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Race | Black | 1.58 (1.51–1.65) | 1.55 (1.47–1.64) | 1.52 (1.44–1.61) | 1.39 (1.31–1.48) | 1.15 (1.05–1.26) | 0.03 |

| Hispanic | 1.38 (1.31–1.46) | 1.48 (1.39–1.56) | 1.39 (1.31–1.47) | 1.3 (1.23–1.37) | 1.1 (1.01–1.2) | <0.01 | |

| Asian | 0.89 (0.81–0.98) | 0.9 (0.82–1) | 0.81 (0.73–0.9) | 0.85 (0.77–0.93) | 0.92 (0.8–1.06) | 0.03 | |

| Other | 1.27 (1.2–1.35) | 1.37 (1.28–1.47) | 1.33 (1.24–1.43) | 1.08 (1.01–1.15) | 0.98 (0.89–1.07) | 0.29 | |

| White | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Urbanicity | Nonurban | 1.19 (1.15–1.23) | 1.18 (1.13–1.23) | 1.15 (1.09–1.2) | 1.14 (1.09–1.19) | 1.12 (1.05–1.2) | 0.94 |

| Urban | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Highest parental education | >High school | 0.75 (0.7–0.8) | 0.65 (0.6–0.7) | 0.69 (0.64–0.74) | 0.76 (0.71–0.82) | 0.92 (0.81–1.04) | <0.01 |

| High school | 0.88 (0.83–0.94) | 0.85 (0.79–0.92) | 0.85 (0.78–0.93) | 0.86 (0.79–0.94) | 1.05 (0.91–1.21) | 0.99 | |

| <High school | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Age, y | 18–19 | 0.43 (0.4–0.46) | 0.41 (0.38–0.44) | 0.44 (0.41–0.48) | 0.41 (0.38–0.45) | 0.44 (0.39–0.49) | 0.38 |

| 16–17 | 0.51 (0.49–0.53) | 0.5 (0.48–0.53) | 0.54 (0.51–0.57) | 0.52 (0.49–0.55) | 0.46 (0.42–0.5) | 0.36 | |

| 14–15 | 0.74 (0.72–0.77) | 0.76 (0.72–0.8) | 0.79 (0.75–0.83) | 0.77 (0.73–0.81) | 0.68 (0.63–0.74) | 0.07 | |

| 12–13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.18 | |

The interaction with each variable was tested by year, with year modeled as a continuous variable to determine whether the magnitude of the odds ratios (ORs) were increasing or decreasing over time. CI, confidence interval.

Tests of interaction with time period indicated substantial variation in reporting ≥7 hours of sleep by demographic variables. For example, black adolescents were increasingly less likely to report getting adequate sleep per night compared with white adolescents. Furthermore, the relation between age 14 and 15 years and reporting ≥7 hours of sleep, compared with age 12 and 13 years, also changed in magnitude, from 0.7 in 1991–1995 to 0.65 in 2011–2012. Other significant interactions were observed; however, there was no systematic direction in the trend of the variation in these odds ratios.

Associations between demographic characteristics and regularly reporting adequate sleep differed for several demographic variables. Conversely to what was observed for regular ≥7 hours of sleep, black and Hispanic students were more likely to report regularly receiving adequate sleep compared with white subjects, in all time periods. Also conversely to what was observed for regular ≥7 hours of sleep, those in the highest SES strata were less likely to report regular adequate sleep compared with those in the lowest SES strata, in all time periods save for 2011–2012. Tests of interaction with time period indicated variation in reporting adequate sleep over time according to race/ethnicity (differences decreased over time) and SES.

Discussion

The present study used nationally representative multicohort data from >270 000 adolescents to rigorously examine the evidence for a changing distribution of sleep patterns in the United States. Three central findings were documented. First, adolescent self-reported sleep has decreased over the past 20 years. The age group with the largest decrease in the percentage getting ≥7 hours per night is 15-year-old adolescents. Seven hours per night is 2 hours less than the 9 hours recommended by the National Sleep Foundation,24 indicating a particularly concerning trend toward inadequate sleep for a large portion of US adolescents at an important juncture in development. Second, these trends were quantified in an age-period-cohort model that indicated strong and significant age and period effects in adolescent sleep in the United States and across subgroups defined according to gender, race, SES, and urbanicity. Thus, these data indicate that adolescent sleep is declining across all age groups and major sociodemographic subgroups. Cohort effects were also observed for some subgroups, particularly in ≥7 hours of sleep for male subjects, white subjects, and those in urban areas; those in the earliest cohorts, as well as cohorts born in the early 1990s, were more likely to report regular ≥7 hours of sleep compared with all other adolescents. Third, we documented that girls are less likely to regularly report ≥7 hours of sleep and to feel they get adequate sleep, as are black/Hispanic adolescents and those in lower SES strata. Furthermore, the disparity according to race has increased in more recent time periods. Other demographic differences also emerged, notably that racial/ethnic minorities and adolescents in lower SES strata are simultaneously less likely to get ≥7 hours of sleep per night but more likely to report regularly getting adequate sleep; these findings suggest a mismatch exists between actual sleep and perceptions of adequate sleep.

We found that period effects predominantly explain decreases in adolescent sleep in nearly every demographic subgroup examined, including by gender, race, SES, and urbanicity. This finding suggests that the drivers of decreases in adolescent sleep are those that affect all age groups simultaneously and are pervasive in their impact across many diverse demographic groups. For example, although we found that girls are less likely to report regular periods of ≥7 hours of sleep compared with boys in every time period, we also found that girls and boys are both decreasing in sleep and thus that the drivers of this decrease are likely similar across genders. The rapid increases in obesity in the 1990s and early 2000s, which also demonstrate a period effect across this same time frame15 and across all demographic groups studied,25 are one plausible mechanism for the observed trends. Interestingly, available data indicate that increases in obesity began leveling off in ∼2005,26 which roughly corresponds to the time frame in which the downward sloping period effect in sleep also levels off. It is likely, however, that the observed population trends comprise a confluence of mechanisms. Social media,10,27 increasing demands of school and extracurricular activities, and other population-level trends11 may also contribute to decreased sleep duration among US adolescents. Further research unraveling such effects is critical to inform public health approaches to curbing the trends of decreased sleep among adolescents.

We also found that female students, racial/ethnic minorities, and students of lower SES all report less often obtaining ≥7 hours of sleep compared with male subjects, non-Hispanic white subjects, and students of higher SES, respectively. Disparities in sleep quality and duration for racial/ethnic minorities, particularly African-American and Hispanic subjects, as well as subjects of lower SES, are well documented.28–32 A number of factors have been proposed to explain racial/ethnic differences in sleep quality, including housing quality which is on average lower for racial/ethnic minorities, as well as obesity and other conditions (eg, sleep apnea) that disrupt sleep and are seen at higher rates among Black and Hispanic children.33–36

We also note that black and Hispanic students and those of lower SES were less likely to report regularly getting ≥7 hours of sleep (compared with white subjects) but were more likely to report regularly getting adequate sleep. This finding suggests that minority and low SES adolescents are less accurately judging the adequacy of the sleep they are getting compared with white/high SES adolescents (ie, perceiving that insufficient amounts of sleep are adequate) or that white/high SES adolescents are more aware of the 9 hours of sleep per night guideline and thus more likely to judge the sleep that they get as inadequate; it may also be a combination of factors. The available literature indicates racial and socioeconomic differences in attitudes toward sleep, sleep patterns within families, and social activities at night that interfere with sleep, suggesting that cultural norms regarding sleep adequacy may in part underlie the mismatch between actual self-reported hours of sleep and self-reported adequacy of sleep.37,38 Further investigation into disparities in perceptions of adequate sleep, and how this disparity may translate to poor sleep patterns among minority and low SES adolescents, is critical. Our results suggest clear public health targets about health literacy in the definition of adequate sleep, reinforcing to adolescents the importance of sleep duration and quality.

Differences in sleep according to gender were also documented, with girls regularly reporting less sleep. This finding is consistent with several studies that documented lower sleep duration in girls compared with boys.10,39,40 Factors such as increased stress have been proposed to underlie these differences,10,40 although a full pathway has yet to be clarified.

The present study had certain limitations. Sleep duration and assessment of sleep adequacy were based on single items and self-report of the respondent. The survey did not include questions on weekday/weekend wake up and sleep times or sleep quality, which are routinely assessed in studies of adolescent sleep. In addition, Monitoring the Future is a large study with a wide range of measurement topics, such that particular depth in any single area is outside the scope of the larger study. The strengths of our assessments, however, are that question wording and placement, as well as study design and methods, were invariant for the >20 years of data collection. This design enables long-term assessments of historical trends as well as estimating age-period-cohort models; such data are unique in behavioral health, such that limitations in the depth of assessment are outweighed by the ability to assess long-term trends.

Conclusions

Declining reported sleep duration as well as perceptions of adequate sleep among US adolescents is potentially a significant public health concern. The present study provides a rigorous assessment of age, period, and cohort effects in adolescent sleep in the United States using self-reported national data from >270 000 adolescents across >2 decades. Public health approaches to increasing health literacy regarding sleep for adolescents (particularly girls, racial/ethnic minorities, and adolescents from low SES backgrounds) are critical to changing the trajectory of adolescent sleep in the United States.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Dr Keyes drafted the manuscript and led the statistical analysis; Dr Maslowsky supervised the statistical analysis and drafted critical sections of the manuscript; Ms Hamilton conducted the statistical analysis and drafted critical sections of the manuscript; and Dr Schulenberg assisted in the design and implementation of the parent study and provided critical feedback and revisions on the analysis plan and manuscript drafts; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported in part by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA001411, Dr Schulenberg) and the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (K01 AA021511, Dr Keyes) the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health & Society Scholars Program (Dr Maslowsky), and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation grant #71539 (Dr Schulenberg). Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Wolfson AR, Carskadon MA. Understanding adolescents’ sleep patterns and school performance: a critical appraisal. Sleep Med Rev. 2003;7(6):491–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smaldone A, Honig JC, Byrne MW. Sleepless in America: inadequate sleep and relationships to health and well-being of our nation’s children. Pediatrics. 2007;119(suppl 1):S29–S37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meldrum RC, Restivo E. The behavioral and health consequences of sleep deprivation among US high school students: relative deprivation matters. Prev Med. 2014;63:24–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Dea JA, Dibley MJ, Rankin NM. Low sleep and low socioeconomic status predict high body mass index: a 4-year longitudinal study of Australian schoolchildren. Pediatr Obes. 2012;7(4):295–303 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Spiers N, Bebbington P, McManus S, Brugha TS, Jenkins R, Meltzer H. Age and birth cohort differences in the prevalence of common mental disorder in England: National Psychiatric Morbidity Surveys 1993-2007. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198(6):479–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laberge L, Petit D, Simard C, Vitaro F, Tremblay RE, Montplaisir J. Development of sleep patterns in early adolescence. J Sleep Res. 2001;10(1):59–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Condén E, Ekselius L, Aslund C. Type D personality is associated with sleep problems in adolescents. Results from a population-based cohort study of Swedish adolescents. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74(4):290–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen G, Ratcliffe J, Olds T, Magarey A, Jones M, Leslie E. BMI, health behaviors, and quality of life in children and adolescents: a school-based study. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/133/4/e868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matricciani L, Olds T, Williams M. A review of evidence for the claim that children are sleeping less than in the past. Sleep. 2011;34(5):651–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Xing Y. Restricted sleep among adolescents: prevalence, incidence, persistence, and associated factors. Behav Sleep Med. 2011;9(1):18–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cain N, Gradisar M. Electronic media use and sleep in school-aged children and adolescents: a review. Sleep Med. 2010;11(8):735–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lenhart A. Teens and mobile phones over the past five years: Pew Internet looks back. Available at: www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media//Files/Reports/2009/PIP Teens and Mobile Phones Data Memo.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2014

- 13.Jones M, Ginsburg KR. Less Stress, More Success: A New Approach to Guiding Your Teen Through College Admissions and Beyond. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matricciani L, Olds T, Petkov J. In search of lost sleep: secular trends in the sleep time of school-aged children and adolescents. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16(3):203–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keyes KM, Utz RL, Robinson W, Li G. What is a cohort effect? Comparison of three statistical methods for modeling cohort effects in obesity prevalence in the United States, 1971-2006. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(7):1100–1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Miech R. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2013: Volume I, Secondary School Students. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2014

- 17.Elder GH. Children of the Great Depression: Social Change in Life Experience. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1974 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keyes KM, Nicholson R, Kinley J, et al. Age, period, and cohort effects in psychological distress in the United States and Canada. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179(10):1216–1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miech R, Bohnert A, Heard K, Boardman J. Increasing use of nonmedical analgesics among younger cohorts in the United States: a birth cohort effect. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(1):35–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Clayton D, Schifflers E. Models for temporal variation in cancer rates. II: age-period-cohort models. Stat Med. 1987;6(4):469–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clayton D, Schifflers E. Models for temporal variation in cancer rates. I: age-period and age-cohort models. Stat Med. 1987;6(4):449–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maslowsky J, Ozer EJ. Developmental trends in sleep duration in adolescence and young adulthood: evidence from a national United States sample. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(6):691–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Yang Y, Schulhofer-Wohl S, Fu WJ, Land KC. The Intrinsic Estimator for age-period-cohort analysis: what it is and how to use it. Am J Sociol. 2008;113(6):1697–1736 [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Sleep Foundation. Teens and sleep. Available at: www.sleepfoundation.org/article/sleep-topics/teens-and-sleep. Accessed August 25, 2014

- 25.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2013: With Special Feature on Prescription Drugs. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2014 [PubMed]

- 26.Xi B, Mi J, Zhao M, et al. Trends in abdominal obesity among US children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/134/2/e334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peiró-Velert C, Valencia-Peris A, González LM, García-Massó X, Serra-Añó P, Devís-Devís J. Screen media usage, sleep time and academic performance in adolescents: clustering a self-organizing maps analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel NP, Grandner MA, Xie D, Branas CC, Gooneratne N. “Sleep disparity” in the population: poor sleep quality is strongly associated with poverty and ethnicity. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whinnery J, Jackson N, Rattanaumpawan P, Grandner MA. Short and long sleep duration associated with race/ethnicity, sociodemographics, and socioeconomic position. Sleep. 2014;37(3):601–611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stranges S, Dorn JM, Shipley MJ, et al. Correlates of short and long sleep duration: a cross-cultural comparison between the United Kingdom and the United States: the Whitehall II Study and the Western New York Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(12):1353–1364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spilsbury JC, Storfer-Isser A, Drotar D, et al. Sleep behavior in an urban US sample of school-aged children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(10):988–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stein MA, Mendelsohn J, Obermeyer WH, Amromin J, Benca R. Sleep and behavior problems in school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2001;107(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/107/4/E60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lallukka T, Arber S, Rahkonen O, Lahelma E. Complaints of insomnia among midlife employed people: the contribution of childhood and present socioeconomic circumstances. Sleep Med. 2010;11(9):828–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Passchier-Vermeer W, Passchier WF. Noise exposure and public health. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(suppl 1):123–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grandner MA, Patel NP, Perlis ML, et al. Obesity, diabetes, and exercise associated with sleep-related complaints in the American population. Z Gesundh Wiss. 2011;19(5):463–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Resta O, Foschino Barbaro MP, Bonfitto P, et al. Low sleep quality and daytime sleepiness in obese patients without obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. J Intern Med. 2003;253(5):536–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McLaughlin Crabtree V, Beal Korhonen J, Montgomery-Downs HE, Faye Jones V, O’Brien LM, Gozal D. Cultural influences on the bedtime behaviors of young children. Sleep Med. 2005;6(4):319–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spilsbury JC, Storfer-Isser A, Drotar D, Rosen CL, Kirchner HL, Redline S. Effects of the home environment on school-aged children’s sleep. Sleep. 2005;28(11):1419–1427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson EO, Roth T, Schultz L, Breslau N. Epidemiology of DSM-IV insomnia in adolescence: lifetime prevalence, chronicity, and an emergent gender difference. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/117/2/e247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petrov ME, Lichstein KL, Baldwin CM. Prevalence of sleep disorders by sex and ethnicity among older adolescents and emerging adults: relations to daytime functioning, working memory and mental health. J Adolesc. 2014;37(5):587–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.