Abstract

Primary myelofibrosis (PMF) is characterized by megakaryocyte hyperplasia, dysplasia and death with progressive reticulin/collagen fibrosis in marrow and hematopoiesis in extramedullary sites. The mechanism of fibrosis was investigated by comparing TGF-β1 signaling of marrow and spleen of patients with PMF and of non-diseased individuals. Expression of 39 (23 up-regulated and 16 down-regulated) and 38 (8 up-regulated and 30 down-regulated) TGF-β1 signaling genes was altered in marrow and spleen of PMF patients, respectively. Abnormalities included genes of TGF-β1 signaling, cell cycling and abnormal in chronic myeloid leukemia (EVI1 and p21CIP) (both marrow and spleen) and Hedgehog (marrow only) and p53 (spleen only) signaling. Pathway analyses of these alterations predict increased osteoblast differentiation, ineffective hematopoiesis and fibrosis driven by non-canonical TGF-β1 signaling in marrow and increased proliferation and defective DNA repair in spleen. Since activation of non-canonical TGF-β1 signaling is associated with fibrosis in autoimmune diseases, the hypothesis that fibrosis in PMF results from an autoimmune process triggered by dead megakaryocytes was tested by determining that PMF patients expressed plasma levels of mitochondrial DNA and anti-mitochondrial antibodies greater than normal controls. These data identify autoimmunity as a possible cause of marrow fibrosis in PMF.

Keywords: TGF-β1, myelofibrosis, autoimmunity, inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Fibrosis is the pathological manifestation of end-stage organ failure in numerous clinical conditions ranging from systemic sclerosis, myocardial infarction, liver cirrhosis, cystic fibrosis to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (reviewed in 1). To identify possible treatments for these diseases, studies in animal models and primary tissues have been performed to define the mechanism(s) that determines occurrence of fibrosis in different organs. It is now recognized that fibrosis results from deregulation of the normal process of wound healing driven by TGF-β which alters the equilibrium between biosynthesis of the extracellular matrix by activated fibroblasts and its degradation by scavenger cells.

In inflammation, fibrosis results from fibroblasts activated by TGF-β over-expression through canonical SMAD signaling (reviewed in1,2 and Table S1). The expression signatures of organs affected by inflammation-related fibrosis include increased expression of TGF-β and increased activity of its downstream elements SMAD2/3 which control the transcription of COL1A1 and COL1A2, the genes encoding for the pro-α1 and pro-α2 chains of collagen type I. These signatures also include down-regulation of BMP7, the TGF-β family member that antagonizes TGF-β, and of its down-stream partners SMAD2/SMAD7 (transcriptional repressors) and p533–5. In human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transgenic mice, an animal model for kidney fibrosis, inflammation induces an oxidative stress that increases the content of homeo-domain interacting protein 2 (HIPK2) which in turn activates TGF-β expression and canonical TGF-β signaling6.

By contrast, in animal models and patients with fibrosis associated with systemic sclerosis, a genetic autosomal dominant form of autoimmune scleroderma, fibroblasts are activated by ERK and/or p38, two members of the non-canonical MAPK TGF-β signaling7,8 (Table S1). Although the levels of active TGF-β in a transgenic mouse model carrying the scleroderma-specific fibrillin-1 mutation (Fbn1) are normal, treatment of these mice with either neutralizing TGF-β antibodies or inhibitors of ERK signaling reduced the presence of autoimmune biomarkers (antinuclear and anti-topoisomerase I antibodies) in blood and prevented skin fibrosis7. Additional genes of the non-canonical TGF-β signaling, or that inhibit canonical TGF-β signaling, that have been described over-expressed in fibrotic organs of patients affected by autoimmune diseases are JUN/JUNB, GADD45B, EVI1, STAT1 and IL-6 (see Table S1).

Primary myelofibrosis (PMF), the most severe of the Philadelphia-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms, is characterized by hematopoietic failure, fibrosis and osteosclerosis in bone marrow (BM) and hematopoiesis in extramedullary sites9 and is associated with megakaryocyte (MK) hyperplasia, dysplasia and death by a pathological process of neutrophil emperipolesis10. Whether in PMF TGF-β1 is implicated in BM fibrosis is still debated. BM from these patients contain increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNFα11 while those of total and bioactive TGF-β1 are only 0.5-two-fold superior to normal12,13. However, ablation of TGF-β1 cures animal models induced by gain-of-function of thrombopoietin (TPOhigh mice) or loss-of function of Gata1 (Gata1low mice), respectively the growth factor and the transcription factor that control MK maturation13,14. TPOhigh mice express high levels of TGF-β114. As Fbn1-mice7, Gata1low mice express normal levels of TGF-β1 but express distinctive TGF-β1 signaling abnormalities in BM and spleen that are rescued by treatment with the TGF-β1 inhibitor13.

To clarify the role of TGF-β1 in determining fibrosis in PMF, TGF-β1 signaling of BM and spleen from the patients was profiled using an array similar to that previously investigated to study Gata1low mice. This profile identified that the TGF-β1 signaling signature of BM and spleen of PMF patients is clearly abnormal, confirming a role for this growth factor in the pathogenesis of this disease. The altered signature of BM indicated activation of non-canonical TGF-β signaling, suggesting the existence in these patients of an underlying autoimmune process. This hypothesis was tested by determining that the plasma of PMF patients contain levels of cell-free mitochondrial DNA and anti-mitochondrial antibodies greater than normal. The recognition that in PMF fibrosis may be associated with activation of non-canonical TGF-β signaling identifies novel possible pharmaceutical targets for this disease.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Human Subjects

Signalling profiling was performed on mononuclear cells obtained from BM (n=3) and spleen (n=6) of patients, normal BM (n=3) (ABM008F-BM3366, ABM008F-BM3527 and ABM008F–BM3600, ALLCELLS, Emeryville, CA) and spleen (n=3) from males (<30-years old) who underwent splenectomy following trauma. BM was obtained from JAK2V617F patients while spleen was obtained from four JAK2V617F-mutated, one MPL-mutated and one triple negative JAK2V617F, CALR and MPL patient (Table S2). Cell-free DNA and auto-antibodies were determined on blood from 40 PMF patients within 0–6 months from diagnosis (Table S3). Inclusion criteria for this study were to be consecutive patients not treated with disease modifying agents such as chemotherapy, immunomodulators or JAK2 inhibitors. Seven out of the 40 patients analyzed had received hydroxyurea. Blood from non-diseased de-identified individuals (n=18–30) and essential thrombocythemia [ET, n=12, 8 patients from the Center for the Study of Myelofibrosis of IRCCS Policlinico S. Matteo, Pavia, Italy (Table S3) and 4 patients from the Tissue Bank of the Myeloproliferative Disease Consortium] as control. Diagnosis was established according to WHO criteria15,16. All the samples were collected according to guidelines established by local ethical committees for human subject studies in accordance with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration revised in 2000.

TGF-β pathway profiling

RNA was prepared from mononuclear cells lysed in Trizol (Gibco BRL, Paisley, UK). Reverse transcription was performed with the RT2 First Strand kit (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD). cDNA was dissolved in the RT2 SYBR ROX qPCR Mastermix and profiled with the Human TGF-β RT2 Profiler™ PCR array (SABiosciences) using glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) as housekeeping control, as described by the manufacturer. Amplification reactions were performed with the ABI 7300 Real Time PCR System (SDS, Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). Biological consequences of gene expression alterations were predicted with the David Bioinformatic Database (David Bioinformatics Resources 6.7 NIAID/NIH). In selected cases, results obtained by microarray were validated by quantitative RT-PCR using primers specific for each gene (SABiosciences). Cycle thresholds (Ct) were calculated with the SDS software and expressed as 2−ΔCt using G3PDH as calibrator. Fold changes were calculated as average 2−ΔCt of the gene in the tested population/average 2−ΔCt of the same gene in non-diseased controls and used to calculate values of fold regulation using the SABioscience program.

Cell-free mitochondrial (mDNA) and nuclear (nDNA) DNA determinations in plasma

Cell-free DNA was isolated from 1 mL of plasma using a QIAamp Blood DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions, dissolved in SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) and amplified [10 ng/reaction] by real-time PCR using primers specific for human cytochrome c oxidase subunit III (forward 5′-ATGACCCACCAATCACATGC-3′ and reverse 5′-ATCACATGGCTAGGCCGGAG-3′)(mDNA) or human α-globin (forward 5′-CTC TTC TGG TCC CCA CAG ACT-3′ and reverse 5′-GGC CTT GAC GTT GGT CTT G-3′) (nDNA). Plasma levels of mDNA and nDNA were expressed in arbitrary units by multiplying reverse Cts per amount of cell-free DNA recovered per mL of plasma.

Determinations of anti-mitochondrial (AMA) and anti-nuclear (ANA) antibodies in plasma

Plasma levels of AMA were quantified with a kit that detects auto-antibodies against mitochondrial proteins for diagnosis of autoimmune liver cirrhosis17 (cat. No. MBS260123, MyBioSource, San Diego, CA). Plasma levels of ANA were assessed with a semi-quantitative kit that determines presence of antibodies against DNA fragments and intracellular nuclear proteins for diagnosis of autoimmune systemic sclerosis18 (cat. No. 3205, Alpha Diagnostic Int., San Antonio, TX).

Statistical methods

Results were expressed as mean (±SD) and analyzed with Anova using Origin 6.0 for Windows (Microcal Software, Inc., Northampton, MA). Values among groups were considered significantly different with a p value < 0.05. TGF-β pathway profilings were analysed with the RT2Profiler™ PCR Array Data Analysis (SABioscience). Genes were considered differentially expressed when the mean fold regulation was ≥ two-fold with a p value < 0.05 (2-tailed, Student’s t-test).

RESULTS

Non-canonical MAPK-dependent TGF-β signaling is activated in BM from PMF patients

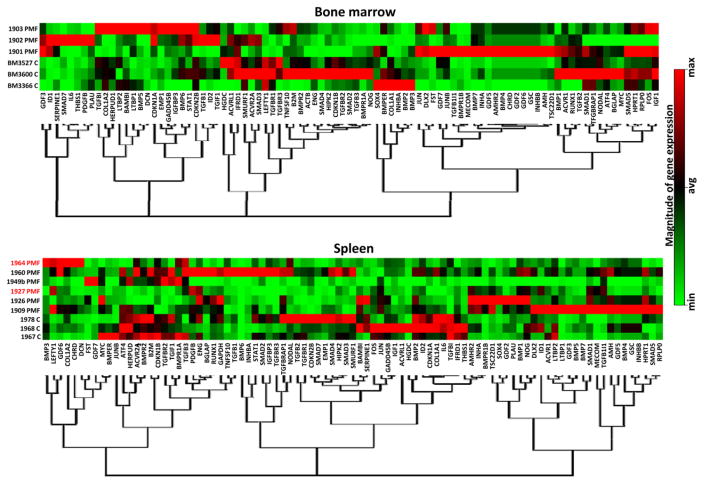

Microarray profiling identified abnormal expression of several TGF-β signaling genes in BM of PMF patients (Figure 1 and Table 1). Twenty-three genes were up-regulated by two-to-seventeen-fold and 16 down-regulated by two-to-ten-fold. Of those, two were significantly up-regulated (GDF3 and p21CIP1) while three were significantly down-regulated (COL1A1, LEFTY1 and TGFBR1).

Figure 1. The bone marrow and spleen of PMF patients present unique alteration signatures of TGF-β signalling.

Hierarchical clustering of normalized gene expression in bone marrow and spleen from non-diseased volunteers (controls, C, n=3) and PMF patients. Results were obtained with BM from three JAK2V617F-mutated PMF patients and spleen from four JAK2V617F-mutated (in black) and two JAK2V617F-mutated PMF patients.

Table 1.

Fold regulation and p-value of genes differentially expressed in PMF patients with respect to non-diseased controls. Differences statistically significant are in bold.

| BM | Over Expressed | Under Expressed | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Fold Reg. | p-values | Fold Reg. | p-values |

| AMHR2 | 5.4264 | 0.137 | ||

| BGLAP | −2.2397 | 0.392 | ||

| BMP2 | −4.6697 | 0.104 | ||

| BMP3 | −8.5544 | 0.215 | ||

| BMP4 | 5.4264 | 0.137 | ||

| BMP7 | 6.8369 | 0.053 | ||

| BMPR1A | −2.2921 | 0.238 | ||

| CHRD | 5.4264 | 0.137 | ||

| COL1A1 | −10.0794 | 0.022 | ||

| COL1A2 | −7.2267 | 0.556 | ||

| DLX2 | 7.4643 | 0.071 | ||

| ENG | −2.0753 | 0.174 | ||

| EVI1 | 2.9828 | 0.371 | ||

| FST | 3.6723 | 0.138 | ||

| GADD45B* | 3.6638 | 0.117 | ||

| GDF2 | 5.4264 | 0.137 | ||

| GDF3 | 8 | 0.027 | ||

| GDF5 | 3.1529 | 0.16 | ||

| GDF6 | 5.4264 | 0.137 | ||

| GSC | 5.4264 | 0.137 | ||

| ID1 | 17.1484 | 0.08 | ||

| IL6 | 15.9631 | 0.328 | ||

| INHA | 5.2416 | 0.128 | ||

| INHBA | −7.0453 | 0.109 | ||

| INHBB | 5.4264 | 0.137 | ||

| JUN | 2.5847 | 0.084 | ||

| LEFTY1 | −3.6301 | 0.00003 | ||

| LTBP1 | 2.1535 | 0.176 | ||

| LTBP2 | 2.114 | 0.771 | ||

| NODAL | −2.3457 | 0.167 | ||

| NOG | −5.3641 | 0.129 | ||

| P21CIP1 (CDKN1A) | 6.9003 | 0.034 | ||

| P27KIP1* | −2.5669 | 0.07 | ||

| SMAD2 | −2.7638 | 0.078 | ||

| STAT1 | 2.0801 | 0.222 | ||

| TGFB1I1 | 2.4623 | 0.291 | ||

| TGFB3 | −3.9541 | 0.084 | ||

| TGFBR1 | −2.1337 | 0.046 | ||

| TGFBR2 | −2.783 | 0.092 | ||

| Spleen | Over Expressed | Under Expressed | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Fold Reg. | p-values | Fold Reg. | p-values |

| ACVR2A | −2.0139 | 0.1822 | ||

| ACVRL1* | −2.514 | 0.1304 | ||

| BAMBI | −2.0946 | 0.5669 | ||

| BMP1 | 2.308 | 0.1189 | ||

| BMP2 | −2.7069 | 0.0364 | ||

| BMPER | −2.3214 | 0.1458 | ||

| BMPR1B | 4.7076 | 0.2322 | ||

| BMPR2 | −2.4938 | 0.0036 | ||

| COL1A1 | −5.9107 | 0.0321 | ||

| EMP1* | −8.1587 | 0.1945 | ||

| EVI1 | 20.3694 | 0.1139 | ||

| FOS | −2.5907 | 0.0597 | ||

| FST | 4.1506 | 0.2393 | ||

| GADD45B* | −2.4967 | 0.0612 | ||

| GDF3 | 2.1861 | 0.3304 | ||

| HERPUD1* | −2.783 | 0.0785 | ||

| HIPK2* | −2.0849 | 0.2538 | ||

| ID2 | −2.2553 | 0.0286 | ||

| IFRD1* | −2.5817 | 0.0028 | ||

| IGF1 | −3.9908 | 0.0329 | ||

| IL6 | −3.9404 | 0.0071 | ||

| JUNB | −2.1361 | 0.074 | ||

| LEFTY1 | 2.9519 | 0.1136 | ||

| LTBP1 | 20.2054 | 0.2331 | ||

| NODAL | −2.4481 | 0.3805 | ||

| P15INK4B (CDKN2B) | −2.3376 | 0.08 | ||

| P21CIP1 (CDKN1A) | −3.1131 | 0.0116 | ||

| SMAD3 | −3.5105 | 0.0606 | ||

| SMAD7* | −11.043 | 0.0379 | ||

| SMURF1 | −2.3054 | 0.1731 | ||

| TGFB1I1 | 6.5206 | 0.0145 | ||

| TGFB2 | −4.8906 | 0.0272 | ||

| TGFBI | −8.9693 | 0.0001 | ||

| TGFBR1 | −3.8415 | 0.0109 | ||

| TGFBR2 | −2.8646 | 0.3092 | ||

| TGFBR3 | −2.8547 | 0.7777 | ||

| TGIF1* | −2.0777 | 0.3115 | ||

| THBS1* | −10.01 | 0.0048 | ||

The genes are color coded to facilitate comparison with results obtained in the Gata1low animal model: white, altered only in PMF, green altered both in PMF and in untreated Gata1low mice, yellow, altered both in PMF patients and in vehicle-treated Gata1low mice; pink, altered in PMF patients, in untreated and in vehicle-treated Gata1low mice,

not present in the mouse array.

The mouse microarray data may be retrieved from the GEO website:

The human microarray data may be retrieved from the GEO website:

In the spleen of PMF patients, 8 genes were up-regulated and 30 down-regulated. Only one gene (TGFB1I1) was significantly up-regulated while 13 genes (BMP2, BMPR2, COL1A1, ID2, IFRD1, IGF1, IL-6, p21CIP1, SMAD7, TGFB2, TGFBI, TGFBR1 and THBS1) were significantly down-regulated (Table 1). Of note, the analysis of microarray data restricted to spleen of the three JAK2V617F-mutated patients gave results super-imposable to those obtained including data from both JAK2V617F-mutated and JAK2V617F-non mutated patients (compare Table 1 and Table S4).

The majority of the abnormalities observed were unique either for BM (25 out of 39 genes) or spleen (25 out of 31 genes) (Table 1 and Figure S1). Only 10 genes were altered in the same direction in both organs: four up-regulated (FST, EVI1, LTBP1 and TGFB1I1) and six down-regulated (BMP2, BMP3, COL1A1, NODAL, TGFBR1 and TGFBR2). Of those, only COL1A1 was significantly down-regulated in both organs. Three genes were up-regulated in BM and down-regulated in spleen (p21Cip1, GADD45B and ID1) and one down-regulated in BM and up-regulated in spleen (LEFTY). Alterations were statistically significant only for p21CIP1, a gene encoding a protein downstream to the RAC pathway that inhibits apoptosis19 and expressed at low levels in stem/progenitor cells from Gata1low mice20.

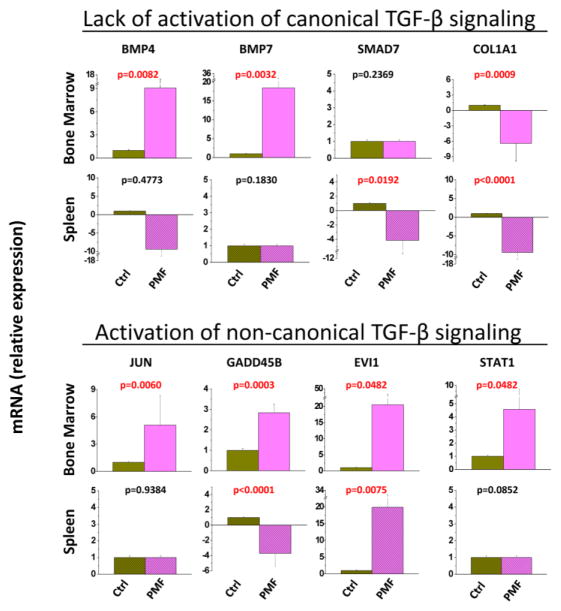

The alteration signatures of BM and spleen of PMF patients lacked markers of canonical TGF-β signaling (such as up-regulation of COL1A1 and HIPK2 and down-regulation of BMT7 and STAT1) associated with fibrosis related to inflammation. By contrast, it contained abnormalities suggesting activation of the non-canonical TGF-β signaling observed in fibrotic tissues of autoimmune disorders (up-regulation of JUN/JUNB, EVI1 and STAT1) (Tables 1 and S1). These indications were validated by comparing the expression of selected genes involved in non-canonical (JUN, GADD45B, EVI1 and STAT1) and canonical (BMP4, BMP7, SMAD7 and COL1A1) TGF-β signaling by quantitative RT-PCR (Figures 2 and S1). This analysis also indicated that the up-regulation of GADD45B observed in the spleen of PMF patients is statistically significant.

Figure 2. Quantitative RT-PCR validation that the alteration signatures of bone marrow and spleen of PMF patients predict activation of non-canonical (up-regulation of JUN, GADD45B, EVI1 and STAT1) rather than canonical (down-regulation of BMP4, BMP7, SMAD7, STAT1, and up-regulation of COL1A1), TGF-β signaling.

Results are expressed in relative units considering the expression in the corresponding organs from non diseased volunteers (Ctrl) as 1 and are presented as mean (±SD) of values observed with BM from three PMF patients and three non-diseased individuals and with spleen from five PMF patients and three non-diseased individuals (the same samples analyzed in Figure 1). To allow appreciation of the difference in gene expression between BM and spleen, Figure S1 presents results from both BM and spleen expressed in relative units considering values in BM from non diseased volunteers as 1.

Additional phenotypes of PMF patients predicted by the abnormal TGF-β signaling signatures of their BM and spleen

David pathway analyses of all genes that were abnormally expressed in BM of patients with PMF identified alterations in TGF-β, Hedgehog, and MAPK signaling and in genes that control cell cycle or are activated in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) and solid cancers (Table 2). Abnormalities observed in canonical SMAD-dependent TGF-β pathway predict increased osteoblast differentiation, G1 arrest and apoptosis, and reduced ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, a pathway indispensable for erythroid maturation21. Abnormalities observed in non-canonical MAPK-dependent TGF-β pathway predict increased apoptosis and fibrosis and include up-regulation of EVI1, a gene whose over-expression in stem/progenitor cells induces loss of response to erythropoietin and impairs erythroid differentiation in mice22,23. Predictions of increased G1 arrest and apoptosis are consistent with the hematopoietic failure observed in BM of PMF patients. In addition, the combination of reduced ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis and increased expression of EVI1 may explain why in PMF BM activation of the stress pathway predicted by the observed up-regulation of BMP424 is not sufficient to increase erythropoiesis at levels sufficient to compensate anemia. Over-expression of EVI1 in mice enhances megakaryocyte proliferation and in humans is associated with hematopoietic disorders characterized by dysmegakaryopoiesis22. Therefore, over-expression of EVI1 is also consistent with the increased megakaryopoiesis observed in BM of PMF patients and suggests that EVI1 may be the element downstream of the activated p38-MAPK signaling that controls megakaryopoiesis in primary myelofibrosis25. Increased G1 arrest and apoptosis in BM are also predicted by alterations observed in genes controlling cell cycle or involved in CML (Table 2).

Table 2.

Biological consequences predicted by the David pathway analyses of the TGF-β signaling abnormalities observed in PMF patients

| Nr of genes | Pathway | Genes | Predicted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marrow | 20 | Canonical TGF-β signaling |

|

Osteoblast differentiation ↑ G1 arrest, apoptosis ↑ Ubiquitin mediated proteolysis ↓ |

| 6 | MAPK signaling |

|

Apoptosis ↑ Fibrosis ↑ |

|

| 3 | Hedgehog signaling |

|

Stress Pathway↑ | |

| 0 | p53 signaling | No hit | - | |

| 5 | Cell Cycle |

|

G1 arrest, apoptosis ↑ | |

| 6 | CML |

|

G1 arrest, apoptosis ↑ | |

| 12 | Pathways in cancer |

|

- | |

| Spleen | 18 | Canonical TGF-β signaling |

|

G1 arrest, apoptosis ↑ Fibrosis ↑ Ubiquitin mediated proteolysis ↓ |

| 6 | MAPK signaling |

|

G1 arrest, apoptosis ↓ DNA repair and damage prevention ↓ |

|

| 0 | Hedgehog signaling | No hit | - | |

| 4 | p53 signaling | P21CIP1, GADD45B, IDF1, THBS1 | G1 arrest, apoptosis ↓ DNA repair and damage prevention ↓ |

|

| 5 | Cell Cycle | SMAD3, P21CIP1, P15INK4B, GADD45B, TGFB2 | G1 arrest, apoptosis ↓ DNA repair and damage prevention ↓ |

|

| 6 | CML |

|

G1 arrest, apoptosis ↑ | |

| 11 | Pathways in cancer |

|

- |

Legend: RED over-expressed; GREEN under-expressed

By contrast, David pathway analyses of all genes abnormally expressed in spleen did not consistently predict G1 arrest and apoptosis. Abnormalities observed in canonical TGF-β signaling and in genes associated with CML (EVI1 up-regulation) and those observed in non-canonical TGF-β and p53 signaling and in cell cycle control predict, respectively, increased and reduced levels of G1 arrest and apoptosis. It is possible that increased G1 arrest and apoptosis reflect the fate of hematopoietic precursors, which fail to mature in the spleen while reduced G1 arrest and apoptosis reflect the great stem/progenitor cells amplification occurring in this organ26. The hypothesis that the spleen microenvironment may favor amplification of the PMF stem cell clone but not that of its hematopoietic precursors is also supported by a comparison of alterations of NODAL and LEFTY, two members of the TGF-β superfamily, observed in BM and spleen. NODAL cooperates with fibroblast growth factor to maintain embryonic stem cells in a pluripotent state27 while LEFTY antagonizes NODAL by inhibiting proliferation and inducing apoptosis28. Expression of NODAL and LEFTY were both down-regulated in BM, in agreement with the poor hematopoietic supportive ability of this microenvironment, but NODAL was down-regulated and LEFTY up-regulated in spleen, consistent with the idea that the spleen microenvironment promotes generation of hematopoietic progenitor cells from the stem cell compartment (down-regulation of NODAL) but then inhibits their maturation by inducing apoptosis (up-regulation of LEFTY). The poor erythroid maturation support provided by spleen of PMF patients is also suggested by the observation that, in spite of anemia, BMP4 was not up-regulated and HIPK2 (homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2) a gene the deletion of which inhibits terminal erythroid maturation in mice29, was down-regulated in this organ. By contrast, under-expression of THBS1 (thrombospondin 1, a suppressor of megakaryopoiesis also known as TSP30) may explain the great number of MK present in spleen of PMF patients.

Of particular interest are the different alterations in GADD45B expression observed in BM, up-regulated, and spleen, down-regulated (Table 1 and Figure 2). Since GADD45B promotes repair and damage prevention of DNA in response to stress31, its down-regulation only in spleen may explain genomic instability and chromosomal abnormality accumulation occurring in hematopoietic stem cells in this organ32.

The plasma from PMF patients contains increased levels of mDNA and AMA

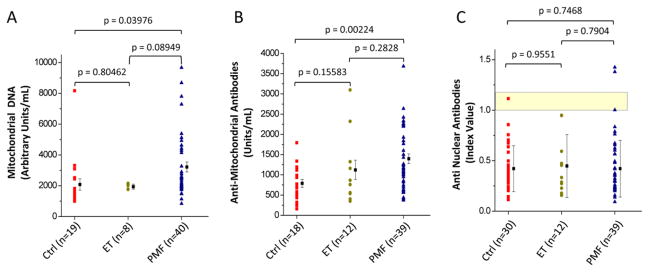

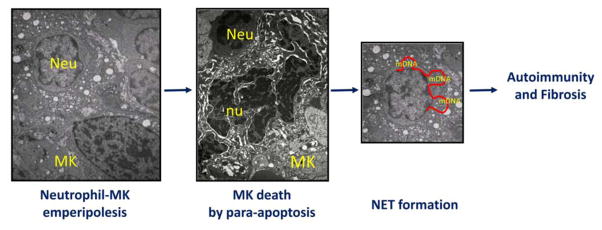

In cystic fibrosis, neutrophils presenting extracellular traps (NET) of autologous DNA released by cells dying for the autoimmune reaction are responsible for fibroblast activation and fibrosis33. Morphological evidence exists in support of the hypothesis that NET may be generated also in PMF. In fact, BM of PMF patients contain numerous neutrophils engaged in a process of pathological emperipolesis with MK that results in death of MK by para-apoptosis10,34. It is possible that during this process, neutrophils may form NET of mitochondrial and/or nuclear DNA released by the dead MK triggering fibrosis. To test this hypothesis, levels of mDNA and nDNA and AMA and ANA in plasma of a cohort of PMF patients (n=39–40) were compared to those present in plasma of ET patients (n=8–12) and non-diseased controls (n=18–30) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Plasma from PMF patients contains levels greater than normal of cell-free mitochondrial DNA (A) and anti-mitochondrial antibodies (B) and normal levels of antinuclear antibodies (C).

Results are expressed as individual values (symbols) and as mean (±SD) of values (columns) from non-diseased volunteers (Ctrl), essential thrombocythemia (ET) and primary myelofibrosis (PMF) patients. The same individuals were analyzed in A–C. The numbers of individuals included in each cohort is indicated in parenthesis. The yellow area in C indicates the range of optical density observed in the standards provided by the Kit as negative controls. See Material and Methods for further details.

Plasma from PMF patients contained levels of both mDNA and AMA significantly greater by 1.5–2-fold than that of controls. By contrast, nDNA was detected only in 1 out of 7 PMF patients analyzed and ANA was present at levels not statistically different from those observed in controls (Figure 3). Failure to detect nDNA and ANA in plasma from PMF patients may reflect the fact that the para-apoptotic process leaves intact the nuclear membrane35 preventing exposure of genomic DNA and intranuclear proteins to immune cells.

DISCUSSION

The data described here indicate that, in spite the nearly normal levels of TGF-β detected in PMF patient so far12,13, the TGF-β signaling profiling of BM and spleen of these patients is clearly altered. David-assisted pathway analyses identified similarities but also important differences in the biological consequences of the TGF-β signaling signatures of BM and spleen from these patients. Alterations of canonical TGF-β signaling predicted increased G1 arrest and apoptosis in both organs but increased osteoblast differentiation in BM only. Alterations in non-canonical TGF-β signaling predicted increased G1 arrest/apoptosis and fibrosis in BM and reduced DNA repair and damage prevention in spleen.

By inductive reasoning that generalizes the concept that non-canonical TGF-β signaling mediates fibrosis in autoimmune diseases, we hypothesized that in PMF BM fibrosis is an autoimmune manifestation triggered by NET formed during the process of pathological MK/neutrophil emperipolesis (Figure 4). This hypothesis was tested by demonstrating that the plasma of PMF patients contains levels of mDNA and AMA greater than normal. These results confirm a previous hypothesis for the presence of autoimmune dysfunction in PMF36 based on reports indicating that plasma of PMF patients contains antibodies against red cells and platelets37 and that the risk to develop myeloproliferative neoplasms is significantly increased by a prior history of autoimmune diseases38.

Figure 4. A model for establishment of the autoimmune process possibly leading to fibrosis in PMF.

Neutrophils presenting extracellular traps (NET) of autologous DNA trigger autoimmune reactions resulting in fibrosis in cystic fibrosis (Reviewed in ref 33). Using this mechanism as a foundation, we propose here that NET formed by mitochondrial DNA released by MK dying of para-apoptosis during the process of pathological emperipolesis with neutrophils (refs 10, 34, 35) may trigger the autoimmune reaction leading to fibrosis in PMF. Legend: Neu = neutrophil; MK = megakaryocyte; nu = para-apoptotic nucleus; mDNA = mitochondrial DNA.

In spite of some differences related to species-specific differences in organ functions, striking similarities were observed in the signature of TGF-β signaling abnormalities of BM and spleen in PMF patients and in the Gata1low mouse model (Figure S3). The majority of the signature abnormalities common to BM of PMF patients and Gata1low mice, including increased expression of two of the markers for autoimmune fibrosis (STAT1 and IL-6) were normalized in the animal model by treatment with the TGF-β inhibitor that rescued its myelofibrotic phenotype13. This observation suggests that treatment with TGF-β inhibitors may also cure PMF patients. This hypothesis was partially confirmed by a recent clinical trial with GC1008, a human immunoglobulin G4 kappa monoclonal antibody that neutralizes each of the mammalian isoforms of TGF-β39 that provided evidence for reduced fibrosis in at least one of the three patients treated. This antibody is no longer available for investigation in PMF. However, the evidence that the non-canonical MAPK-driven TGF-β signaling is responsible for fibrosis in PMF provided here suggests that this antibody may be replaced by interferon-α, a compound that targets the p38-MAPK pathway40,41 currently undergoing clinical investigation in PMF, or by anyone of the eight ERK inhibitors and five p38 inhibitors already approved by FDA for clinical use in other cancers42,43.

CONCLUSION

TGF-β signaling profiling provides evidence that BM fibrosis characterizing PMF patients is the consequence of activation of non-canonical MAPK-driven TGF-β signaling pathway. Since by contrast with SMAD signaling, inhibitors of non-canonical MAPK-driven TGF-β signaling are already used in the clinic, the expression profiling described in this study paves the way for future investigations that may lead to the identification of novel approaches for treatment of this disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (P01-CA108671), the Italian Ministry of Education (FIRB2010 accordi di programma), Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro and “Special Program Molecular Clinical Oncology 5x1000” (to AIRC-Gruppo Italiano Malattie Mieloproliferative). http://www.progettoagimm.it. Dr. Scott Friedman, Yujin Hoshida and Ronald Hoffman are gratefully acknowledged for discussion and advice.

Footnotes

AUTHORSHIP AND CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENTS

Fiorella Ciaffoni, Elena Cassella and Margherita Massa performed experiments and analyzed data.

Giovanni Barosi provided samples from PMF patients and normal donors and assured compliance of the study with institutional IRB.

Anna Rita Migliaccio, Lilian Varricchio and Giovanni Barosi designed research, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

All the authors have read the manuscript, concur with its content and state that its content has not been submitted elsewhere.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURE: FC, EC, LV, MM, GB, and ARM declare no competing financial interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ghosh AK, Quaggin SE, Vaughan DE. Molecular basis of organ fibrosis: potential therapeutic approaches. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2013;238:461–481. doi: 10.1177/1535370213489441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Massague J, Blain SW, Lo RS. TGFbeta signaling in growth control, cancer, and heritable disorders. Cell. 2000;103:295–309. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kinoshita K, Iimuro Y, Otogawa K, Saika S, Inagaki Y, Nakajima Y, Kawada N, Fujimoto J, Friedman SL, Ikeda K. Adenovirus-mediated expression of BMP-7 suppresses the development of liver fibrosis in rats. Gut. 2007;56:706–714. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.092460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukasawa H, Yamamoto T, Togawa A, Ohashi N, Fujigaki Y, Oda T, Uchida C, Kitagawa K, Hattori T, Suzuki S, Kitagawa M, Hishida A. Down-regulation of Smad7 expression by ubiquitin-dependent degradation contributes to renal fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8687–8692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400035101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu GX, Li YQ, Huang XR, Wei L, Chen HY, Shi YJ, Heuchel RL, Lan HY. Disruption of Smad7 promotes ANG II-mediated renal inflammation and fibrosis via Sp1-TGF-beta/Smad3-NF.kappaB-dependent mechanisms in mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin Y, Ratnam K, Chuang PY, Fan Y, Zhong Y, Dai Y, Mazloom AR, Chen EY, D’Agati V, Xiong H, Ross MJ, Chen N, Ma’ayan A, He JC. A systems approach identifies HIPK2 as a key regulator of kidney fibrosis. Nat Med. 2012;18:580–588. doi: 10.1038/nm.2685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerber EE, Gallo EM, Fontana SC, Davis EC, Wigley FM, Huso DL, Dietz HC. Integrin-modulating therapy prevents fibrosis and autoimmunity in mouse models of scleroderma. Nature. 2013;503:126–130. doi: 10.1038/nature12614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akhmetshina A, Palumbo K, Dees C, Bergmann C, Venalis P, Zerr P, Horn A, Kireva T, Beyer C, Zwerina J, Schneider H, Sadowski A, Riener MO, MacDougald OA, Distler O, Schett G, Distler JH. Activation of canonical Wnt signalling is required for TGF-beta-mediated fibrosis. Nat Commun. 2012;3:735. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tefferi A. Myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1255–1265. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004273421706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmitt A, Jouault H, Guichard J, Wendling F, Drouin A, Cramer EM. Pathologic interaction between megakaryocytes and polymorphonuclear leukocytes in myelofibrosis. Blood. 2000;96:1342–1347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleischman AG, Aichberger KJ, Luty SB, Bumm TG, Petersen CL, Doratotaj S, Vasudevan KB, LaTocha DH, Yang F, Press RD, Loriaux MM, Pahl HL, Silver RT, Agarwal A, O’Hare T, Druker BJ, Bagby GC, Deininger MW. TNFalpha facilitates clonal expansion of JAK2V617F positive cells in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2011;118:6392–6398. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campanelli R, Rosti V, Villani L, Castagno M, Moretti E, Bonetti E, Bergamaschi G, Balduini A, Barosi G, Massa M. Evaluation of the bioactive and total transforming growth factor beta1 levels in primary myelofibrosis. Cytokine. 2011;53:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.07.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zingariello M, Martelli F, Ciaffoni F, Masiello F, Ghinassi B, D’Amore E, Massa M, Barosi G, Sancillo L, Li X, Goldberg JD, Rana RA, Migliaccio AR. Characterization of the TGF-beta1 signaling abnormalities in the Gata1low mouse model of myelofibrosis. Blood. 2013;121:3345–3363. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-439661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chagraoui H, Komura E, Tulliez M, Giraudier S, Vainchenker W, Wendling F. Prominent role of TGF-beta 1 in thrombopoietin-induced myelofibrosis in mice. Blood. 2002;100:3495–3503. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tefferi A, Thiele J, Orazi A, Kvasnicka HM, Barbui T, Hanson CA, Barosi G, Verstovsek S, Birgegard G, Mesa R, Reilly JT, Gisslinger H, Vannucchi AM, Cervantes F, Finazzi G, Hoffman R, Gilliland DG, Bloomfield CD, Vardiman JW. Proposals and rationale for revision of the World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and primary myelofibrosis: recommendations from an ad hoc international expert panel. Blood. 2007;110:1092–1097. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-083501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gangat N, Caramazza D, Vaidya R, George G, Begna K, Schwager S, Van Dyke D, Hanson C, Wu W, Pardanani A, Cervantes F, Passamonti F, Tefferi A. DIPSS plus: a refined Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System for primary myelofibrosis that incorporates prognostic information from karyotype, platelet count, and transfusion status. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:392–397. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanaka A, Miyakawa H, Luketic VA, Kaplan M, Storch WB, Gershwin ME. The diagnostic value of anti-mitochondrial antibodies, especially in primary biliary cirrhosis. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2002;48:295–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grassegger A, Pohla-Gubo G, Frauscher M, Hintner H. Autoantibodies in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma): clues for clinical evaluation, prognosis and pathogenesis. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2008;158:19–28. doi: 10.1007/s10354-007-0451-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gu Y, Filippi MD, Cancelas JA, Siefring JE, Williams EP, Jasti AC, Harris CE, Lee AW, Prabhakar R, Atkinson SJ, Kwiatkowski DJ, Williams DA. Hematopoietic cell regulation by Rac1 and Rac2 guanosine triphosphatases. Science. 2003;302:445–449. doi: 10.1126/science.1088485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verrucci M, Pancrazzi A, Aracil M, Martelli F, Guglielmelli P, Zingariello M, Ghinassi B, D’Amore E, Jimeno J, Vannucchi AM, Migliaccio AR. CXCR4-independent rescue of the myeloproliferative defect of the Gata1low myelofibrosis mouse model by Aplidin. J Cell Physiol. 2010;225:490–499. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khandros E, Thom CS, D’Souza J, Weiss MJ. Integrated protein quality-control pathways regulate free alpha-globin in murine beta-thalassemia. Blood. 2012;119:5265–5275. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-397729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buonamici S, Li D, Chi Y, Zhao R, Wang X, Brace L, Ni H, Saunthararajah Y, Nucifora G. EVI1 induces myelodysplastic syndrome in mice. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:713–719. doi: 10.1172/JCI21716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kreider BL, Orkin SH, Ihle JN. Loss of erythropoietin responsiveness in erythroid progenitors due to expression of the Evi-1 myeloid-transforming gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:6454–6458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paulson RF, Shi L, Wu DC. Stress erythropoiesis: new signals and new stress progenitor cells. Curr Opin Hematol. 2011;18:139–145. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32834521c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desterke C, Bilhou-Nabera C, Guerton B, Martinaud C, Tonetti C, Clay D, Guglielmelli P, Vannucchi A, Bordessoule D, Hasselbalch H, Dupriez B, Benzoubir N, Bourgeade MF, Pierre-Louis O, Lazar V, Vainchenker W, Bennaceur-Griscelli A, Gisslinger H, Giraudier S, Le Bousse-Kerdiles MC. FLT3-mediated p38-MAPK activation participates in the control of megakaryopoiesis in primary myelofibrosis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2901–2915. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X, Prakash S, Lu M, Tripodi J, Ye F, Najfeld V, Li Y, Schwartz M, Weinberg R, Roda P, Orazi A, Hoffman R. Spleens of myelofibrosis patients contain malignant hematopoietic stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3888–3899. doi: 10.1172/JCI64397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vallier L, Alexander M, Pedersen RA. Activin/Nodal and FGF pathways cooperate to maintain pluripotency of human embryonic stem cells. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4495–4509. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang YQ, Sterling L, Stotland A, Hua H, Kritzik M, Sarvetnick N. Nodal and lefty signaling regulates the growth of pancreatic cells. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:1255–1267. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hattangadi SM, Burke KA, Lodish HF. Homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2 plays an important role in normal terminal erythroid differentiation. Blood. 2010;115:4853–4861. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang M, Li K, Ng MH, Yuen PM, Fok TF, Li CK, Hogg PJ, Chong BH. Thrombospondin-1 inhibits in vitro megakaryocytopoiesis via CD36. Thromb Res. 2003;109:47–54. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(03)00142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liebermann DA, Tront JS, Sha X, Mukherjee K, Mohamed-Hadley A, Hoffman B. Gadd45 stress sensors in malignancy and leukemia. Crit Rev Oncog. 2011;16:129–140. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v16.i1-2.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Malley DP, Orazi A, Wang M, Cheng L. Analysis of loss of heterozygosity and X chromosome inactivation in spleens with myeloproliferative disorders and acute myeloid leukemia. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1562–1568. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saffarzadeh M, Preissner KT. Fighting against the dark side of neutrophil extracellular traps in disease: manoeuvres for host protection. Curr Opin Hematol. 2013;20:3–9. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32835a0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centurione L, Di Baldassarre A, Zingariello M, Bosco D, Gatta V, Rana RA, Langella V, Di Virgilio A, Vannucchi AM, Migliaccio AR. Increased and pathologic emperipolesis of neutrophils within megakaryocytes associated with marrow fibrosis in GATA-1low mice. Blood. 2004;104:3573–3580. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thiele J, Lorenzen J, Manich B, Kvasnicka HM, Zirbes TK, Fischer R. Apoptosis (programmed cell death) in idiopathic (primary) osteo-/myelofibrosis: naked nuclei in megakaryopoiesis reveal features of para-apoptosis. Acta Haematol. 1997;97:137–143. doi: 10.1159/000203671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barosi G, Magrini U, Gale RP. Does auto-immunity contribute to anemia in myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN)-associated myelofibrosis? Leuk Res. 2010;34:1119–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barcellini W, Iurlo A, Radice T, Imperiali FG, Zaninoni A, Fattizzo B, Guidotti F, Bianchi P, Fermo E, Consonni D, Cortelezzi A. Increased prevalence of autoimmune phenomena in myelofibrosis: relationship with clinical and morphological characteristics, and with immunoregulatory cytokine patterns. Leuk Res. 2013;37:1509–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kristinsson SY, Landgren O, Samuelsson J, Bjorkholm M, Goldin LR. Autoimmunity and the risk of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Haematologica. 2010;95:1216–1220. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.020412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mascarenhas J, Li T, Sandy L, Newsom C, Petersen B, Godbold J, Hoffman R. Anti-transforming growth factor-beta therapy in patients with myelofibrosis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55:450–452. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.805329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu M, Zhang W, Li Y, Berenzon D, Wang X, Wang J, Mascarenhas J, Xu M, Hoffman R. Interferon-alpha targets JAK2V617F-positive hematopoietic progenitor cells and acts through the p38 MAPK pathway. Exp Hematol. 2010;38:472–480. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Katsoulidis E, Li Y, Yoon P, Sassano A, Altman J, Kannan-Thulasiraman P, Balasubramanian L, Parmar S, Varga J, Tallman MS, Verma A, Platanias LC. Role of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in cytokine-mediated hematopoietic suppression in myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9029–9037. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zawistowski JS, Nakamura K, Parker JS, Granger DA, Golitz BT, Johnson GL. MicroRNA 9-3p targets beta1 integrin to sensitize claudin-low breast cancer cells to MEK inhibition. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:2260–2274. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00269-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang-Yew Leow C, Gerondakis S, Spencer A. MEK inhibitors as a chemotherapeutic intervention in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2013;3:e105. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2013.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.