Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Abstract

Background:

Noroviruses (NoVs) are the leading cause of acute gastroenteritis across all age groups. Because a vaccine is in clinical development, burden of disease data are required to guide the eventual introduction of this vaccine. In this study, we estimate the burden of NoV disease in children less than 5 years of age in the European Union (EU).

Methods:

We carried out a literature search using PubMed to identify studies providing incidence or prevalence data for NoV disease in the EU. We applied the pooled average NoV incidence and prevalence rates to the EU population less than 5 years of age to obtain the annual number of NoV illnesses, medical visits, hospitalizations and deaths occurring in the EU among children younger than 5 years.

Results:

Data from 12 studies were included. We estimate that NoV infection may cause up to 5.7 million illnesses in the community, 800,000 medical visits, 53,000 hospitalizations and 102 deaths every year in children younger than 5 years in the EU.

Conclusion:

The burden of NoV disease in children in the EU is substantial, and will grow in relative importance as rotavirus (RV) vaccines are rolled out in the EU. This burden of disease is comparable with the burden of RV disease in the EU before RV vaccine introduction. More country-specific studies are needed to better assess this burden and guide the potential introduction of a vaccine against NoV at the national level.

Noroviruses (NoV) were identified as a cause of gastroenteritis in 1972,1 but its importance as enteric pathogen was underestimated for many years because of inadequate diagnostic tools.2 Advances in the understanding of molecular biology and the development of novel diagnostic tools have changed our perception of their impact. Noroviruses are now recognized as an important cause of acute gastroenteritis (AGE) in the community3,4 and of food-borne disease worldwide.5 Noroviruses are one of the most common causes of severe gastroenteritis in children less than 5 years of age in developing and industrialized countries, second only to rotaviruses (RVs).6

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the development of vaccines against Norovirus infection with encouraging results.7 In this context, it is important to collect and evaluate accurate data on the burden of disease to provide the basis for informed decisions concerning vaccine introduction. Although several studies aiming to evaluate the burden of disease of Norovirus in European Union (EU) countries have been published,3,4,8,9 these investigations have been restricted to one country or even one region within the country.

In this study, we estimate the burden of Norovirus disease in the EU in children less than 5 years of age using published data.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The objective of this study was to estimate the number of illnesses in the community, the number of medical visits, the number of hospitalizations and the number of deaths in children less than 5 years of age that are attributable to Norovirus disease in the EU (EU-27), using available published data.

Literature Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

We carried out a literature search using PubMed with combination keyword search terms “norovirus AND (children OR pediatr*)” restricted to the period between January 1, 2003 and July 31, 2013.We applied the following inclusion criteria: (1) the study must have an abstract; (2) the study must have been carried out in at least 1 EU country; (3) the study must provide prevalence or incidence data for Norovirus disease in children less than 5 years of age; (4) the study must have been conducted before the introduction of RV vaccines; (5) the study recruitment period had to cover at least 1 year and (6) the diagnosis of Norovirus must have been confirmed by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).

Norovirus Disease Ascertainment

A case of Norovirus disease was defined by a stool sample PCR positive for Norovirus regardless of the presence of other pathogens.

Norovirus Disease at the Community Level, Medical Visits and Hospitalizations

We used two approaches to estimate the number of cases of Norovirus disease occurring in the community, Norovirus-related medical visits and Norovirus-related hospitalizations. For the first approach (Method 1), we calculated the weighted average incidence found for Norovirus disease from studies carried out in the EU. If no incidence data were found for the EU, studies reporting incidence from other high-income countries were taken.

Because the number of studies reporting Norovirus incidence is limited, an alternative approach (Method 2) was also used; we calculated the ratio of the proportion of Norovirus hospital prevalence to the proportion of RV hospital prevalence and applied this ratio to the incidence previously estimated for RV hospitalizations in the EU.10 A meta-analysis was performed to estimate the proportions of AGE hospitalizations caused by Norovirus and RV. In particular, we applied the Freeman & Tuckey-transformed proportions11 to the Der Simonian and Laird random effects model.12

Then, applying the method described by Parashar et al13 for RV disease, we assumed that for each episode of Norovirus disease requiring hospitalization, there are 8 (range 5–10) episodes of Norovirus disease requiring a medical visit, and that for every episode of Norovirus disease requiring a medical visit there are 4 (range 3–5) episodes that require only home care. To estimate the absolute number of Norovirus cases, we applied the incidences obtained to the country level and total EU-27 population of children less than 5 years of age (last year available, 2012).14 We estimated the risk of Norovirus disease, medical visit and hospitalizations by age 5 by dividing the number of total live births in the EU-27 (last year available, 2011)14 by the estimated annual number of Norovirus disease episodes.

Norovirus Disease Leading to Death

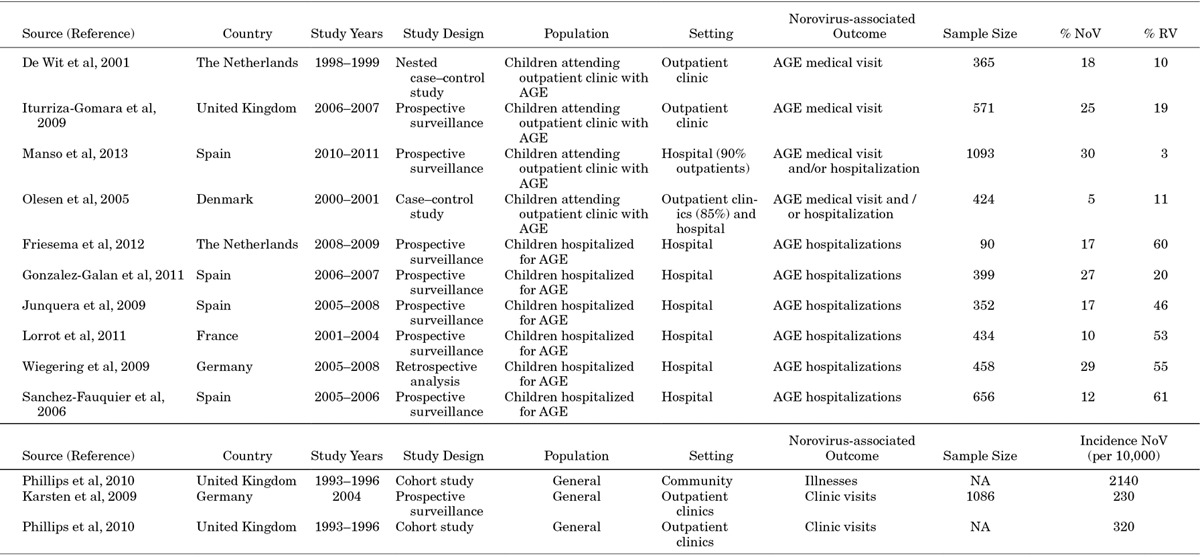

To estimate the number of deaths due to Norovirus infection, we used the model described by Parashar et al.13 We obtained the mortality rates per 1000 live births for children younger than 5 years15 for the latest year available (2011), as well as the number of live births in each country for the same year.14 Applying the mortality rate to the number of live births, we calculated the estimated number of total deaths in children less than 5 years of age per country. We then divided the 27 countries of the EU according to the World Bank income group classification according to gross national income (GNI) per capita.16 Twenty-four countries were classified as high income, and 3 countries were classified as upper middle income (Table 1). We then applied the estimated proportion of deaths in children less than 5 years of age attributable to diarrhea as calculated by Parashar et al.13 These estimates put the proportion of deaths attributable to diarrhea at 1% for high-income countries and at 9% for upper middle-income countries. Applying these proportions to the total number of deaths per country, we obtained the country-specific number of deaths attributable to diarrhea. Finally, to estimate the number of deaths attributable to Norovirus, we applied the proportion of AGE hospitalizations attributable to Norovirus to the country-specific number of deaths. This assumes that the proportion of AGE hospitalizations attributable to Norovirus corresponds to the proportion of diarrhea deaths attributable to NoV.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the Studies Selected

We estimated the risk of Norovirus disease leading to death by age 5 by dividing the number of total live births in the EU-2714 by the estimated annual number of Norovirus disease episodes leading to death.

RESULTS

Literature Search

We identified 634 publications of which 602 had an available abstract. Sixty of these studies were original studies carried out in EU countries. Two papers were excluded because they did not provide any data on incidence or prevalence of Norovirus disease. One study was excluded because it tested for Calicivirus, without specific results for Norovirus. One study was excluded because it reported only nosocomial disease data and another one for providing data from outbreaks only. Six studies were excluded because the recruitment period was less than 12 months. Seventeen studies were excluded because RT-PCR was not used to confirm the diagnosis in all or part of the samples. A further 18 studies were excluded because they did not provide data specifically for children less than 5 years of age, and 2 because they did not provide prevalence data for RV disease. We finally identified 12 studies, 6 providing hospitalization prevalence data,17–22 4 providing medical visit prevalence data3,23–25 and 2 providing community and/or medical visit incidence data,4,9 representing 6 countries (The Netherlands, Spain, the United Kingdom, Denmark, France and Germany). A summary of the studies included is shown in Table 1.

Norovirus Burden of Disease

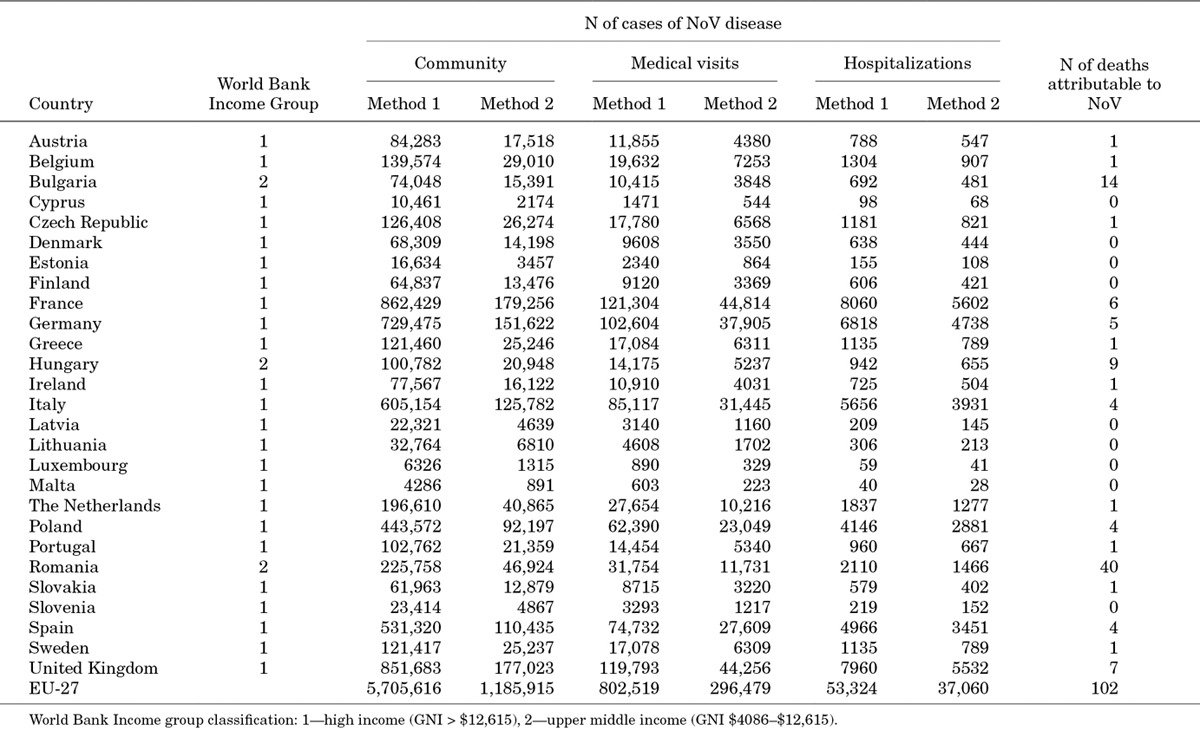

The results are summarized in Table 2. According to Eurostat,14 the total population younger than 5 years in the EU-27 was 26,661,758 for the year 2012, whereas the birth cohort was 5,229,813 for the year 2011.

TABLE 2.

Estimates of the Burden of NoV Disease in the EU-27: Number of Cases of NoV Disease in the Community, Leading to a Medical Visit, Leading to a Hospitalization and Leading to Death

Norovirus Disease in the Community

We identified a single data source providing data on the incidence of Norovirus disease in the community.4 This study estimated the incidence at 2140 cases of Norovirus disease per 10,000 children less than 5 years of age [95% confidence interval (CI): 1590–2770]. Applying this incidence to the number of children younger than 5 years, we estimated that 5.7 million cases of Norovirus disease occur every year in the EU within this age group (95% CI: 4.2–7.4 million), which translates to a risk of one in one of suffering an episode of Norovirus disease by age 5. Using the alternative approach (Method 2), we estimated that 1.2 million cases (range 929,962–1,808,734) of Norovirus disease occur every year in the EU.

Norovirus Disease Leading to a Medical Visit

We identified two data sources that provided data on the incidence of Norovirus disease leading to a medical visit.4,9 The average estimate was calculated at 301 cases (95% CI: 230–370) of Norovirus disease per 10,000 children less than 5 years of age. Applying this incidence to the number of children younger than 5 years, we estimated that 800,000 cases of Norovirus disease leading to a medical visit occur every year in the EU in this age group (95% CI: 613,000–986,000). This translates to a risk of 1 in 7 of suffering an episode of Norovirus disease leading to a medical visit by age 5.

Using the alternative approach, we estimated that 296,000 cases of Norovirus disease leading to a medical visit occur every year in the EU (range 232,000–452,000).

Norovirus Disease Leading to Hospitalization

We could not find any studies carried out in the EU providing AGE hospitalization incidence attributable to Norovirus. However, we identified 2 studies outside the EU (the US and Israel) that provided these data.26,27 The mid-point incidence estimate was 20 hospitalizations caused by Norovirus disease per 10,000 children less than 5 years of age. Applying this incidence to the number of children younger than 5 years, we estimated that 53,000 hospitalizations attributable to Norovirus occur every year in the EU. This translates to a risk of 1 in 98 of suffering an episode of Norovirus disease leading to a hospitalization by age 5.

Using the alternative approach, we identified 6 data sources that provided data on the prevalence of Norovirus disease among hospitalized children.17–22 We estimated that Norovirus represents 18% of all AGE hospitalizations (95% CI: 12.3–24.9 %), whereas RV represents 48% (95% CI 35.6–61.1%), with a ratio of 0.376 to 1 (95% CI 0.35–0.41). Applying this ratio to the estimated incidence of AGE hospitalizations due to RV (37 per 10,000, range 29–56.5)10 provided an estimated incidence for hospitalization due to Norovirus of 14 per 10,000 (range 10.9–21.2), resulting in an estimated 37,000 hospitalizations attributable to Norovirus in children less than 5 years of age every year in the EU (range 29,000–57,000).

Norovirus Disease Leading to Death

We estimated the total number of deaths in children less than 5 years of age in the EU to be 25,000 per year. Among these, we estimated 560 to be caused by diarrhea. After applying the percentage of AGE hospitalizations caused by Norovirus, we estimated that every year Norovirus disease causes 102 deaths in children less than 5 years of age in the EU (95% CI 69–139). This translates to a risk of 1 in 51,000 of suffering an episode of Norovirus disease leading to death by age 5 (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/INF/C18).

DISCUSSION

Norovirus disease is considered to be the leading cause of AGE in all age groups in the community, and the second cause of severe AGE requiring hospitalization among children less than 5 years old.3,4,6 However, the latter may change in the future with the progressive introduction of RV vaccination in national immunization programs. Studies in the US and Finland have already demonstrated that Norovirus has become the primary cause of AGE hospitalization after the introduction of RV vaccine in these countries.26,28 With a vaccine against Norovirus currently in clinical development,7 it becomes important to assess the burden of disease to guide a potential introduction of the vaccine in immunization programs. This study presents for the first time an estimation of the burden of Norovirus disease in the EU region specifically. We chose to evaluate the burden of disease using two different approaches: first by applying incidences for Norovirus disease obtained from published literature, and second by comparing the burden of disease of Norovirus to RV. Using the first approach, we estimated that every year 5.7 million cases of illness, 800,000 medical visits and 53,000 hospitalizations attributable to Norovirus occur in children younger than 5 years of age. Taking the alternative approach the estimates were 1.2 million illnesses, 296,000 medical visits and 37,000 hospitalizations. We also projected that 102 deaths were attributable to Norovirus annually in this age group.

Considering the results obtained from Norovirus incidence data, virtually all children will have suffered at least one episode of Norovirus illness by age 5, 1 in 7 children will have required a medical visit, 1 in 98 will have been hospitalized and 1 in 51,000 will have died.

Nevertheless, the findings of our study present several limitations. The two approaches yielded different estimates, particularly the estimates obtained for the number of total illnesses and medical visits. Calculation of the total number of illnesses and medical visits through the alternative approach assumed that the ratio of hospitalizations to medical visits (1:8), and the ratio of medical visits to illnesses (1:4) would be basically the same as previously described for RV. If we calculate the same ratios from the numbers obtained from incidence data, we find a hospital to medical visit ratio of 1:15 and a medical visit to illness ratio of 1:7, which would indicate that the course of Norovirus disease progresses to severity less frequently than RV disease. To estimate the incidence of hospitalization due to Norovirus via the alternative approach, we used the ratio of the prevalence of Norovirus and RV infection among patients hospitalized for AGE. This assumes a constant relation between Norovirus and RV infections, whereas in reality it may differ between different locations. With the aim of making a conservative estimate, we only used data from studies carried out before the introduction of RV vaccines.

The studies we identified for inclusion in our evaluation reflected only 5 countries in the EU. We have therefore assumed that incidence and prevalence of Norovirus is comparable for all countries in the EU, which may have led to an over or underestimation of the disease burden. There are currently no data available to support this assumption, given the heterogeneity between studies using different inclusion criteria, different case definitions and different diagnostic methods, precluding easy comparison. A previous study showed the impact of the use of different case definitions, with difference in estimates up to 1.5–2.1 times depending on the case definition used.29

Nosocomial infections have not been considered in the current evaluation for lack of incidence data, which may have underestimated the burden. A review in Germany has shown that up to 16% of Norovirus hospitalizations in children less than 5 years of age may be of nosocomial origin.30 Medical visits do not include emergency department visits because incidence data was only available for clinic visits, which may also have underestimated the burden.

There are few published studies that explore the burden of Norovirus disease at regional or global levels. Recently, there have been two studies looking at the burden of Norovirus disease in the US. Payne et al,26 in a prospective surveillance study, estimated the incidence of clinic visits due to Norovirus disease in children less than 5 years old at 368 cases per 10,000 children, which is slightly higher than our estimate of 301 per 10,000. Conversely, the authors estimated the incidence of hospitalization due to Norovirus disease at 9 per 10,000, whereas we calculated a higher estimate at 14–20 cases per 10,000 children. Gastanaduy et al,31 based on modeling of health insurance data, estimated the incidence of clinic visits due to Norovirus at 233 per 10,000 children, slightly below our estimate. Although the differences may be explained by the use of different case definitions, laboratory techniques or differences in health care services use, all the estimates in principle are comparable.

Two systematic reviews have been undertaken to assess the burden of Norovirus disease at the global level. Patel et al6 estimated that Norovirus caused 12% (95% CI: 9–16%) of all severe gastroenteritis in children, with estimated annual incidences of 12 hospitalizations and 167 medical visits per 10,000 children. Our estimates that Noroviruses are responsible for 18% of AGE hospitalizations and an annual incidence of Norovirus hospitalization of 14–20 per 10,000 are both comparable with Patel’s global estimates. However, our estimated incidence for medical visits is higher than Patel’s (301 versus 167 per 10,000). The discrepancy may be due to our estimation being based on population studies that provided incidence data as opposed to estimating the incidence from the proportion of AGE medical visits attributable to Norovirus disease, or to regional differences or differences in access to medical care. In addition, the two studies used to provide these estimates were not available at the time of Patel’s review.4,9 In a recent review, Lanata et al32 estimated that Norovirus caused 13.8% (95% CI 11.8–17.6%) of all AGE hospitalizations worldwide, and 9.8% of all AGE hospitalizations in the WHO EURO region. Our estimate for Norovirus hospitalizations is comparable with Lanata’s at the global level, but higher when considering only the WHO EURO region (18% versus 9.8%). This difference may be due to the different geographical make up and to the different criteria applied for study selection. Our review only considered for example only studies where Norovirus diagnosis was confirmed by PCR, whereas Lanata et al included other diagnostic methods such as enzyme linked immunosorbent assay.

We have made no attempt to translate the burden of Norovirus disease into economic terms because it was out of the scope of this study. There are currently few studies in the EU that have provided estimates of direct or indirect costs for Norovirus disease. The UK Health Protection Agency, citing data from Lopman et al,33 estimates that Norovirus costs the National Health Service in excess of £100 million per year in years of high incidence (2002–2003 figures).34 In the US, Payne et al26 calculated that the burden of Norovirus disease among children less than 5 years old results in direct health care costs in excess of $273 million every year.

The introduction of RV vaccines has been successful in reducing the burden of (severe) RV AGE.35 The burden of RV disease in the EU before vaccine introduction was estimated at 2.8 million illnesses, 700,000 outpatient visits, 87,000 hospitalizations and 231 deaths.10 Our estimated burden of Norovirus disease exceeds the RV estimates of the total number of illnesses and is comparable in the number of medical visits. Conversely, the burden of hospitalization and death is lower for Norovirus disease compared with RV. Studies in Finland and the US have already shown that Norovirus has become the main cause of severe AGE in children following the introduction of RV vaccination.26,28

The introduction of a vaccine against Norovirus could have important benefits. In a model developed in the US, it was estimated that a vaccine offering 50% efficacy and with a duration of protection of 4 years administered to children less than 5 years of age would avoid 4000 Norovirus disease cases, 685 clinic visits, 18 hospitalizations and 0.02 deaths per 10,000 vaccinations.36

In conclusion, the burden of Norovirus disease in children in the EU is substantial, and a future vaccine against Norovirus could potentially translate into significant health costs and societal savings. More studies will be needed at country level in the EU to better assess this burden and guide the eventual introduction of a vaccine against Norovirus at the national level. To allow comparisons between countries, future standardization of case definitions for AGE and laboratory diagnostics for Norovirus at the EU level would be of the utmost importance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Kaat Bollaerts for her support with data analysis and review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

F.K. and F.Z. have received a grant from Takeda for a study not related to this publication. MRM and TV have received consulting fees from Takeda. The authors have no other funding or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (www.pidj.com).

REFERENCES

- 1.Kapikian AZ, Wyatt RG, Dolin R, et al. Visualization by immune electron microscopy of a 27-nm particle associated with acute infectious nonbacterial gastroenteritis. J Virol. 1972;10:1075–1081. doi: 10.1128/jvi.10.5.1075-1081.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koo HL, Ajami N, Atmar RL, et al. Noroviruses: the leading cause of gastroenteritis worldwide. Discov Med. 2010;10:61–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Wit MA, Koopmans MP, Kortbeek LM, et al. Sensor, a population-based cohort study on gastroenteritis in the Netherlands: incidence and etiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:666–674. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.7.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips G, Tam CC, Conti S, et al. Community incidence of norovirus-associated infectious intestinal disease in England: improved estimates using viral load for norovirus diagnosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:1014–1022. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atmar RL, Estes MK. The epidemiologic and clinical importance of norovirus infection. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2006;35:275–290, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel MM, Widdowson MA, Glass RI, et al. Systematic literature review of role of noroviruses in sporadic gastroenteritis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1224–1231. doi: 10.3201/eid1408.071114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atmar RL, Bernstein DI, Harro CD, et al. Norovirus vaccine against experimental human Norwalk Virus illness. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2178–2187. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1101245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huhulescu S, Kiss R, Brettlecker M, et al. Etiology of acute gastroenteritis in three sentinel general practices, Austria 2007. Infection. 2009;37:103–108. doi: 10.1007/s15010-008-8106-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karsten C, Baumgarte S, Friedrich AW, et al. Incidence and risk factors for community-acquired acute gastroenteritis in north-west Germany in 2004. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:935–943. doi: 10.1007/s10096-009-0729-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soriano-Gabarro M, Mrukowicz J, Vesikari T, et al. Burden of rotavirus disease in European Union countries. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:S7–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000197622.98559.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman MF, Tukey JW. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Ann Math Stat. 1950;21:607–611. [Google Scholar]

- 12.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parashar UD, Hummelman EG, Bresee JS, et al. Global illness and deaths caused by rotavirus disease in children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:565–572. doi: 10.3201/eid0905.020562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eurostat. appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu. Accessed August 8, 2013.

- 15.UNICEF. Millenium development goals indicators. mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/data.aspx. Accessed September 27, 2013.

- 16.World Bank income group country classification 2013. Available at: data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications/country-and-lending-groups. Accessed August 8, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friesema IH, de Boer RF, Duizer E, et al. Etiology of acute gastroenteritis in children requiring hospitalization in the Netherlands. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:405–415. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1320-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez-Galan V, Sánchez-Fauqier A, Obando I, et al. High prevalence of community-acquired norovirus gastroenteritis among hospitalized children: a prospective study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:1895–1899. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Junquera CG, de Baranda CS, Mialdea OG, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of norovirus gastroenteritis among hospitalized children in Spain. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:604–607. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318197c3ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lorrot M, Bon F, El Hajje MJ, et al. Epidemiology and clinical features of gastroenteritis in hospitalised children: prospective survey during a 2-year period in a Parisian hospital, France. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30:361–368. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-1094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanchez-Fauquier A, Montero V, Moreno S, et al. Human rotavirus G9 and G3 as major cause of diarrhea in hospitalized children, Spain. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1536–1541. doi: 10.3201/eid1210.060384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiegering V, Kaiser J, Tappe D, et al. Gastroenteritis in childhood: a retrospective study of 650 hospitalized pediatric patients. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15:e401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iturriza-Gomara M, Elliot AJ, Dockery C, et al. Structured surveillance of infectious intestinal disease in pre-school children in the community: ‘The Nappy Study’. Epidemiol Infect. 2009;137:922–931. doi: 10.1017/S0950268808001556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manso CF, Torres E, Bou G, Romalde JL. Role of norovirus in acute gastroenteritis in the Northwest of Spain during 2010–2011. J Med Virol. 2013;85:2009–2015. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olesen B, Neimann J, Böttiger B, et al. Etiology of diarrhea in young children in Denmark: a case-control study. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3636–3641. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.3636-3641.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Payne DC, Vinjé J, Szilagyi PG, et al. Norovirus and medically attended gastroenteritis in U.S. children. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1121–1130. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1206589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muhsen K, Kassem E, Rubinstein U, et al. Incidence and characteristics of sporadic norovirus gastroenteritis associated with hospitalization of children less than 5 years of age in Israel. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:688–690. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318287fc81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hemming M, Rasanen S, Huhti L, et al. Major reduction of rotavirus, but not norovirus, gastroenteritis in children seen in hospital after the introduction of RotaTeq vaccine into the National Immunization Programme in Finland. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172:739–746. doi: 10.1007/s00431-013-1945-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Majowicz SE, Hall G, Scallan E, et al. A common, symptom-based case definition for gastroenteritis. Epidemiol Infect. 2008;136:886–894. doi: 10.1017/S0950268807009375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spackova M, Altmann D, Eckmanns T, et al. High level of gastrointestinal nosocomial infections in the German surveillance system, 2002–2008. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:1273–1278. doi: 10.1086/657133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gastanaduy PA, Hall AJ, Curns AT, et al. Burden of Norovirus Gastroenteritis in the Ambulatory Setting–United States, 2001–2009. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:1058–1065. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lanata CF, Fischer-Walker CL, Olascoaga AC, et al. Global causes of diarrheal disease mortality in children <5 years of age: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopman BA, Reacher MH, Vipond IB, et al. Epidemiology and cost of nosocomial gastroenteritis, Avon, England, 2002-2003. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1827–1834. doi: 10.3201/eid1010.030941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norovirus Working Party. Guidelines for the management of norovirus outbreaks in acute and community health and social care settings. http://www.hpa.org.uk/webc/hpawebfile/hpaweb_c/1317131639453.Accessed April 15, 2014.

- 35.Yen C, Tate JE, Patel MM, et al. Rotavirus vaccines: update on global impact and future priorities. Hum Vaccin. 2011;7:1282–1290. doi: 10.4161/hv.7.12.18321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bartsch SM, Lopman BA, Hall AJ, et al. The potential economic value of a human norovirus vaccine for the United States. Vaccine. 2012;30:7097–7104. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]