Abstract

Brain areas each generate specific neuron subtypes during development. However, underlying regional variations in neurogenesis strategies and regulatory mechanisms remain poorly understood. In Drosophila, neurons in four optic lobe ganglia originate from two neuroepithelia, the outer (Opc) and inner (Ipc) proliferation centers. Using genetic manipulations, we demonstrate that one Ipc neuroepithelial domain progressively transforms into migratory progenitors that mature into neural stem cells/neuroblasts within a second domain. Progenitors emerge by an epithelial-mesenchymal transition-like mechanism, requiring the Snail-family member Escargot and, in subdomains, Decapentaplegic signaling. The proneural factors Lethal of scute and Asense differentially control progenitor supply and maturation into neuroblasts. These switch expression from Asense to a third proneural protein, Atonal. Dichaete and Tailless mediate this transition essential for generating two neuron populations at defined positions. We propose that this neurogenesis mode is central for setting-up a new proliferative zone to facilitate spatio-temporal matching of neurogenesis and connectivity across ganglia.

INTRODUCTION

Brains in vertebrates and invertebrates are organized into interconnected functionally distinct areas, each consisting of different neuron subtypes. During development, these are generated by neural stem cells (Nsc) that are specified by regional patterning mechanisms. Differences in neurogenesis strategies may further contribute to shaping different brain areas1. However, despite their potential significance in diversifying brain circuitries, our understanding of region-specific neurogenesis modes and the molecules that regulate them is limited.

In the mammalian cerebral cortex, neuroepithelial cells within the ventricular zone give rise to Nsc/radial glia, which divide asymmetrically to self-renew and produce neurons and then glia either directly or via intermediate progenitors2,3. Analogously in the central nervous system (CNS) of Drosophila melanogaster, neuroepithelial cells generate Nsc equivalents, the neuroblasts, by delamination or conversion3,4. Commonly, neuroblasts follow a type I proliferation pattern, undergoing asymmetric divisions to generate another self-renewing neuroblast and a ganglion mother cell (Gmc). The latter in turn divides once to produce two neurons or neurons and glia. In the vertebrate brain, neuron populations often extensively migrate to new areas distinct from the regions, in which they were born5. Little evidence for such migration exists in the fly CNS. However, a previous study had described cell streams linking two domains in one of the proliferative areas in the visual system, called the inner proliferation center, suggesting that migration could be a central feature in this brain region6.

The Drosophila optic lobe consists of four ganglia, the lamina, medulla, lobula plate and lobula. The lamina and medulla receive sensory input from photoreceptor cells (R-cells). All ganglia are innervated by distinct target neuron subtypes7 (Fig. 1a). In the central brain and ventral nerve cord, most neuroblasts become quiescent at the end of embryogenesis, and are re-activated during postembryonic development. By contrast in the larval optic lobe, persisting neuroepithelia form the outer and inner proliferation centers (Opc and Ipc)3,6. They are derived from the embryonic optic lobe placode, which invaginates from the procephalic ectoderm and attaches to the brain hemispheres8. During larval development, the Opc initially expands by symmetric divisions9. Neuroepithelial cells at the medial edge gradually convert into neuroblasts in a proneural wave, whose progression is controlled by at least four signaling pathways10-12. Neuroblasts generate Gmcs and eventually medulla neurons (Fig. 1b). A cascade of specific temporal identity transcription factors drives subtype diversification13,14. By contrast, neuroepithelial cells at the lateral edge generate lamina precursor cells (Lpc). Their proliferation and the differentiation of lamina neurons depend on anterograde R-cell axon-derived signals15,16.

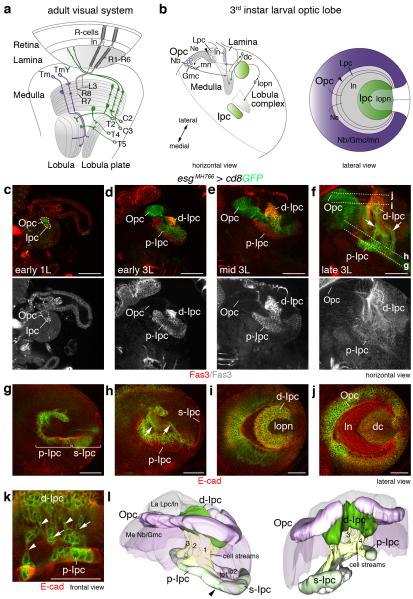

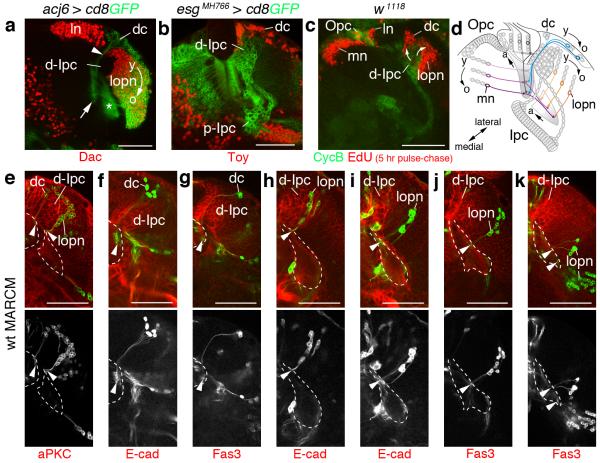

Figure 1. The larval Drosophila optic lobe shows extensive cell streams in the Ipc.

Schematics of adult (a) and third instar larval (b) optic lobes. Outer and inner proliferation center (Opc, Ipc) progeny are shown in purple and green, respectively. dc, distal cells; Gmc, ganglion mother cells; ln, lamina neurons; Lpc, lamina precursor cells; lopn, lobula plate neurons; mn, medulla neurons; neuroblast, Nb; Tm and TmY, transmedullary neurons; arrowheads, lamina furrow. (c-f) escargot (esg)MH766-Gal4, UAS-cd8GFP (green) transgenes label Opc neuroepithelial (Ne) cells, Ipc neuroepithelial cell subsets and their progeny in early first (1L) and early, mid and late third (3L) larval stages. The Ipc and offspring express Fasciclin 3 (Fas3, red). Opc neuroepithelial cells are located superficially, Ipc neuroepithelial cells centrally. Cell streams (arrows) connect the proximal and distal Ipc (p-Ipc, d-Ipc), as their distance increases. Lines (f) indicate focal planes shown in (g–j). esgMH766-Gal4, UAS-cd8GFP and E-cadherin (E-cad, red) labeling shows that the p-Ipc and surface-Ipc (s-Ipc) form an asymmetric horseshoe (indicated by brackets in g), and the d-Ipc a symmetric horseshoe (i). The d-Ipc surrounds lobula plate neurons (i). The superficial Opc and lamina crescents are adjacent to distal cells (j). Cell streams (arrows) consist of interconnected, elongated (arrowheads) cells (h,k). (l) A 3D model shown at two angles illustrates the four main cell streams between the p-Ipc and d-Ipc. The s-Ipc generates the lobula cell clusters lo1 and lo2. arrowhead, p-Ipc/d-Ipc boundary. Detailed genotypes and sample numbers are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Scale bars, 50 μm.

The Ipc produces (1) a larval neuron population named distal cells, whose neurites in the adult extend into the medulla and lobula, or medulla and lamina, (2) lobula plate neurons, whose neurites connect the lobula plate with the medulla or lobula, and (3) lobula neurons6,17,18. Distal cells and lobula plate neurons include C2 and C3 and the motion-detecting T4 and T5 neurons, respectively19,20. Phylogenetic studies in crustaceans and insects proposed that in the ancestral visual system, neurons innervating the lamina and lobula plate originate from two proliferation zones, which are homologous to the Opc and Ipc. Subsequently, in higher arthropod species, their duplication resulted in the formation of two new ganglia, the medulla and lobula21,22. However, how neurons are generated in the Ipc compared to the Opc in the expanded insect visual circuit remains poorly understood.

Using molecular markers and genetic manipulations, we demonstrate that the Ipc domain dedicated to generating distal cells and lobula plate neurons produces offspring in a previously unrecognized neurogenesis mode. Progenitors emerge from the Ipc neuroepithelium in a mechanism resembling epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and migrate within cell streams to a second domain where they acquire Nsc properties. Proneural basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) proteins control the supply rate and maturation of progenitors into neuroblasts, while cross-regulatory interactions of two other transcriptional regulators, acting as switching factors, are essential for the generation of the two neuron populations.

RESULTS

Two Ipc domains are connected by extensive cell streams

To gain insights into Ipc development, we co-stained postembryonic optic lobes with (1) escargot (esg)MH766-Gal4, an enhancer trap insertion identified in this study, that drives expression of membrane-bound green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the Opc, a subset of Ipc neuroepithelial cells and their progeny, and (2) an antibody against the cell adhesion molecule Fasciclin 3 (Fas3) labeling the Ipc and its offspring. This showed that the Ipc differentially expressed Fas3 from the first instar larval stage onwards (Fig. 1c-f). Opc and Ipc neuroepithelia are initially found in close proximity and increase in size during subsequent larval stages9. As progeny arise, the Opc and Ipc separate, with the Opc positioned superficially and the Ipc centrally. Consistent with the earlier study of A. Hofbauer and J.A. Campos-Ortega6, we observed prominent cell streams between two Ipc areas (Fig. 1f).

Further analysis of third instar larval optic lobes in horizontal and lateral orientations and a 3D model revealed that the Ipc consists of three domains. We defined these as the proximal, surface and distal Ipc (p-Ipc, s-Ipc and d-Ipc) (Fig. 1g-l and Supplementary Movie 1). The p-Ipc and s-Ipc contain columnar neuroepithelial cells and form an asymmetric horseshoe close to the central brain. The longer ventral shank of the s-Ipc extends towards the optic lobe surface, and produces lobula neurons in two clusters (Fig. 1g,l; H.A., I.S., unpublished observations). The d-Ipc forms a symmetric horseshoe adjacent to the lamina and Opc crescents. Four main streams of interconnected elongated cells reside between the p-Ipc and d-Ipc (Fig. 1h,k,l).

Cell streams consist of progenitors

To assess the developmental state of Ipc cells, we stained optic lobes with markers for neuroblasts and Gmcs. Neuroblasts are known to express the coiled-coil adaptor protein Miranda (Mira), and the bHLH transcription factors Deadpan (Dpn) and Asense (Ase), while Gmcs express Ase and the homeodomain protein Prospero (Pros)4. We detected cells expressing these markers abutting the s-Ipc but not in or adjacent to the p-Ipc. Remarkably, also cell streams did not show any labeling with Dpn, Ase or Pros and displayed very low levels of cytoplasmic Mira (Fig. 2a-d), suggesting that they consisted of a distinct progenitor type rather than neuroblasts or Gmcs. By contrast, Dpn- and Mira-expressing neuroblasts were found throughout the d-Ipc; some neuroblasts also co-expressed Ase (Fig. 2a,c-g). The horseshoe-shaped d-Ipc centrally contained neuroblasts and interspersed Gmcs, while two zones oriented towards the lamina and the optic lobe surface were enriched in Gmcs. In neuroblasts residing in the lower d-Ipc, the apically localized adapter protein Inscuteable (Insc) frequently pointed towards the lobula plate cortex, while basal Mira and Pros crescents faced the lamina (Fig. 2e-g). This suggests that d-Ipc neuroblasts use oriented asymmetric cell divisions at distinct angles to position their progeny.

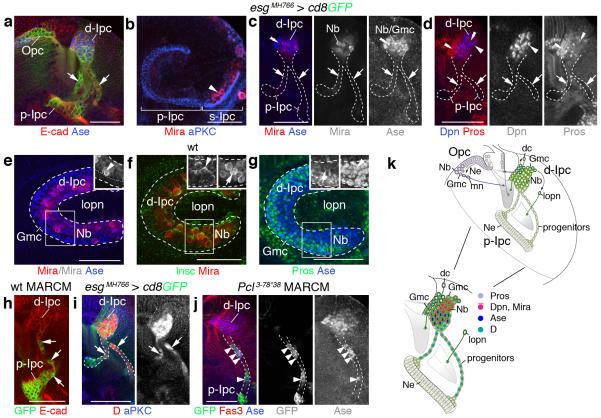

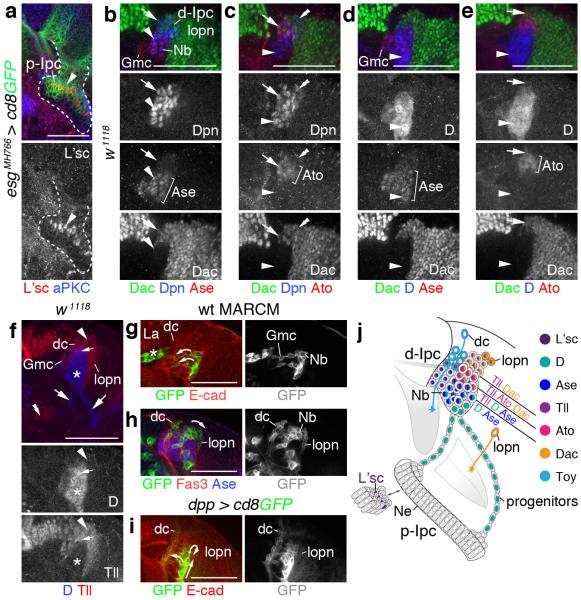

Figure 2. Cell streams in the Ipc consist of progenitors.

(a–d) escargot (esg)MH766-Gal4, UAS-cd8GFP (green; not shown in b–d) delineates the p-Ipc neuroepithelium and cell streams. (a) p-Ipc neuroepithelial cells express E-cadherin (E-cad; red). The d-Ipc contains Asense-positive neuroblasts (Ase+ Nbs, blue). (b) Miranda-positive neuroblasts (Mira+, red, arrowhead) delaminate from the s-Ipc (brackets) visualized with aPKC (blue). (c,d) d-Ipc neuroblasts express Mira (red), Ase (blue) (c) and Deadpan (Dpn, blue) (d). Ganglion mother cells (Gmc) in the lower d-Ipc express Ase (double arrowheads, c). Prospero (Pros, red, d) labels Gmcs intermingled with d-Ipc neuroblasts and in two zones facing the lamina and the optic lobe surface (double arrowheads). Cell streams (arrows) weakly express cytoplasmic Mira but not Ase, Dpn or Pros (c,d). (e) The lower d-Ipc contains centrally Ase+ and Mira+ neuroblasts and Ase+ Gmcs, and peripherally Ase+ Gmcs. (f) In neuroblasts, basal Mira crescents (arrow) are orientated peripherally and apical Inscuteable crescents (Insc, green, arrowheads) centrally. (g) Pros (green) forms basal crescents (arrows) in neuroblasts. Nuclear Pros and Ase (blue) colocalize in Gmcs. (h) Wild type (wt) MARCM clones show that cell streams (arrows) originate from the p-Ipc. (i) Cell streams (arrows) and the d-Ipc express Dichaete (D, red). Polycomblike (Pcl3-78*38) mutant progenitors (green) generated by MARCM (j) prematurely express Ase (blue, arrowheads). (k) Ipc schematic summarizing cellular marker distributions. dc, distal cells; mn, medulla neurons; lopn, lobula plate neurons. b,e–g show lateral views. For genotypes and sample numbers, see Supplementary Table 1. Scale bars, 50 μm.

We next used mosaic analysis with a repressible cellular marker (MARCM)23 for lineage tracing. Clones induced in the p-Ipc extended into cell streams, confirming that they indeed originated from this neuroepithelium (Fig. 2h). Cells within streams and the d-Ipc expressed the group B Sox-domain containing transcription factor Dichaete (D) (Fig. 2i). As D is expressed in medulla neuroblasts13,14, progenitors could be potentially arrested in an interim stage. In parallel, we had performed an ethyl methanesulfonate-based forward genetic mosaic screen for determinants controlling Opc and Ipc development, and identified a novel mutant allele of the epigenetic regulator Polycomblike, named Pcl3-78*38 (H.A., I.S., unpublished observations). Pcl and its vertebrate homolog PHF1 belong to the highly conserved Polycomb group of chromatin-modifying proteins24. Remarkably, Pcl3-78*38 homozygous mutant progenitors prematurely upregulated Ase within cell streams (Fig. 2j). Hence, progenitors have the potential to differentiate into neuroblasts, but are prevented by a mechanism that is sensitive to Pcl loss.

Together, this indicates that p-Ipc neuroepithelial cells give rise to a distinct progenitor population. The organization into cell streams suggests that these progenitors become migratory after leaving the p-Ipc. They acquire Nsc/neuroblast properties within a second proliferative zone, the d-Ipc, where they produce Gmcs and ultimately postmitotic offspring (Fig. 2k).

Progenitors leave the p-Ipc in an EMT-like process

To delaminate from epithelia and acquire motility, cells in certain developmental contexts undergo EMT25. We therefore tested whether Ipc progenitors could be generated by such a mechanism. Snail zinc-finger transcription factors lie at the core of the genetic programs regulating developmental EMT. They inhibit the expression and adhesiveness of E-cadherin (E-cad), inducing the cellular changes associated with the EMT onset25. We focused on Esg as one of four known Drosophila Snail family members26. esgMH766-Gal4 and the independent insertion esg-lacZB7-2-22 showed strong expression in cells that were in the process of leaving the p-Ipc and have entered the cell streams, while remaining neuroepithelial cells were unlabeled. By contrast, E-cad levels were substantially lower in cell streams compared to p-Ipc neuroepithelial cells (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 1a).

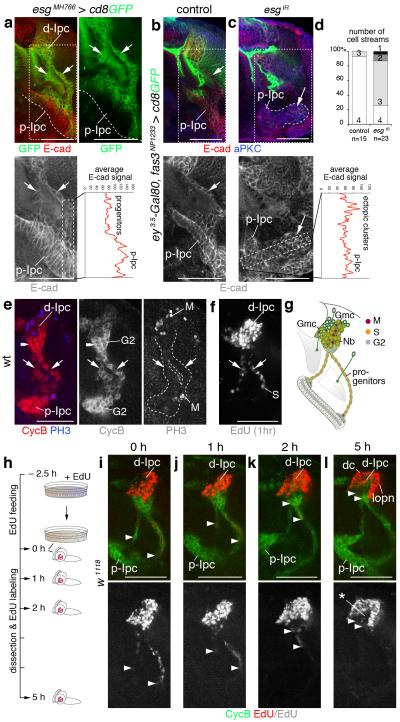

Figure 3. Migratory progenitors arise by epithelial-mesenchymal transition and require escargot (esg).

(a) Progenitors, leaving the p-Ipc (line) and entering cell streams (arrows), upregulate esgMH766-Gal4, UAS-cd8GFP (green) and downregulate E-cadherin (E-cad, red). (b,c) Compared to controls (b), Ipc-specific knockdown of esg (esgIR) using fasciclin3 (fas3)NP1233-Gal4 induces ectopic clusters continuous with the p-Ipc (large arrows, c) that maintain strong E-cad expression. Small arrows indicate one of the streams (b). Graphs show average E-cad fluorescence signals in boxes in left-hand higher-magnification panels. (d) Quantification of main cell stream numbers in controls and upon esg knockdown. (e) p-Ipc neuroepithelial cells strongly express CyclinB (CycB, red). After leaving the p-Ipc, progenitors express phosphoHistone 3 (PH3, blue). (f) Progenitors in streams (arrows), labeled by 1 hour EdU incubation, are in S phase. They enter G2 phase at the d-Ipc base (double arrowheads, e). d-Ipc neuroblasts and ganglion mother cells (Nb/Gmc) undergo S phase and mitosis (e,f). (g) Summary of Ipc cell cycle profile. (h–l) In EdU pulse-chase experiments, brains of wandering third instar larvae were assessed at 0, 1, 2 and 5 hours after 2.5 hours EdU feeding. Arrowheads indicate the most proximal EdU+ (red) progenitors within streams. The distance of EdU+ progenitors to the p-Ipc gradually increases, consistent with migration. After 5 hours, d-Ipc neuroblasts/Gmcs above CycB (green) expressing progenitors are no longer labeled with EdU (asterisk, l). Labeling persists in distal cells (dc) and lobula plate neurons (lopn). For genotypes and sample numbers, see Supplementary Table 1. Scale bars, 50 μm.

To determine whether esg could mediate EMT of cell streams, we combined ey3.5-Gal80, fas3NP1233-Gal4 and RNAi transgenes to specifically knockdown esg in the Ipc (Fig. 3b-d and Supplementary Fig. 1b,c). This caused the formation of ectopic cell clusters adjacent to and continuous with the p-Ipc neuroepithelium in ~50% of examined optic lobes (n=16/30). The partial penetrance of phenotypes is likely due to incomplete knockdown by RNAi transgenes. Ectopic clusters consisted of closely associated cells that maintained high E-cad levels (Fig. 3c). Whereas in controls primarily four main cell streams emerged from the p-Ipc, the number of streams detected upon knockdown was often reduced from 4 to 3, 2 or 1 (Fig. 3d). While not excluding subsequent additional requirements, these data reveal a role for Esg in mediating EMT of cell streams in the Ipc.

Progenitors in cell streams are migratory

We next asked whether progenitors indeed migrate. Neural crest cells in the avian trunk are known to emigrate from the neural tube in S phase27. We therefore established a p-Ipc/d-Ipc cell cycle profile (Fig. 3e-g), using Cyclin B (CycB) and phosphoHistone 3 (PH3) immunolabeling, as well as 5-ethynyl-2′deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation to visualize cells in G2, M and S phase, respectively. While p-Ipc neuroepithelial cells undergo S phase and proliferate during early larval development (Supplementary Fig. 1d), they are in G2 phase in late third instar larvae. Progenitors undergo mitosis shortly after leaving the neuroepithelium, and are in S phase within streams. At the d-Ipc base, progenitors re-enter G2 phase and mature into neuroblasts. These undergo a new round of S phase and mitosis to produce Gmcs and postmitotic progeny.

Based on these findings, we performed additional pulse-chase EdU incorporation assays. Third instar larvae were fed with EdU for 2.5 hours, transferred to fresh food and dissected after 0, 1, 2 and 5 hours (Fig. 3h). We observed that EdU was progressively cleared from progenitors within cell streams, while accumulating in the lower d-Ipc. This indicates that progenitors, which had earlier incorporated EdU, migrated away from the p-Ipc towards the d-Ipc (Fig. 3i-l). After 5 hours, the d-Ipc core was devoid of labeling while EdU-positive (EdU+) cells resided in two adjacent domains. These correspond to newborn distal cells and lobula plate neurons derived from d-Ipc neuroblasts that had incorporated EdU during feeding (Fig. 3l). This demonstrates that the p-Ipc produces migratory progenitors in a mechanism that shares characteristics with EMT although taking place within the brain.

EMT is mediated by Dpp in p-Ipc subdomains

Because progenitors emerged specifically from the p-Ipc, we asked whether EMT could be instructed by spatially controlled signals. We focused on Decapentaplegic (Dpp), because the Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) signaling pathway is commonly associated with EMT28. A Gal4 enhancer trap insertion reported restricted Dpp expression in dorsal and ventral p-Ipc subdomains, and in two cell streams originating from these areas (Fig. 4a,b). Dpp-expressing neuroblasts were distributed along the inner edge of the d-Ipc crescent (Fig. 4c). Brinker (Brk) and Optomotor-blind (Omb) are transcriptional targets of Dpp signaling: brk, encoding a repressor, is downregulated, while omb, encoding an activator, is upregulated29. We observed that in the Ipc, dpp-positive neuroepithelial cells and progenitors strongly expressed omb-lacZ, while brk-lacZ was downregulated (Fig. 4d-f), consistent with pathway activation in dpp expressing domains.

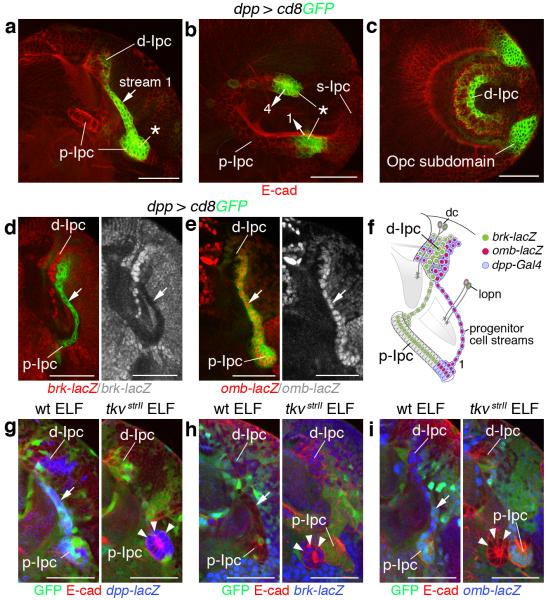

Figure 4. Local Decapentaplegic (Dpp) signaling is required for epithelial-mesenchymal transition in p-Ipc subdomains.

(a-c) dpp-Gal4, UAS-cd8GFP (green) label ventral and dorsal subdomains of the p-Ipc (asterisks), progenitor cell streams 1 and 4 (arrows) and parts of the central d-Ipc. Optic lobes are shown in a horizontal orientation in a (cf. Fig. 1f) and in a lateral orientation in b (cf. Fig. 1g) and c (cf. Fig. 1i). (d,e) dpp-labeled cell streams (arrows) are brinker (brk)-lacZ negative (red, d) and optomotor-blind (omb)-lacZ positive (red, e). (f) Schematic illustrating dpp, omb and brk marker expression in the Ipc. (g–i) Unlike in wild type (wt) (left panels), in thickveins (tkvstrII) ELF mosaics (right panels), mutant GFP-negative cells adjacent to p-Ipc neuroepithelial cells form small ectopic clusters that express dpp-lacZ (blue, arrowheads, g) and brk-lacZ (blue, arrowheads, h), but not omb-lacZ (blue, arrowheads, i). Optic lobes are co-labeled with E-cadherin (E-cad, red, a–c,g–i). For genotypes and sample numbers, see Supplementary Table 1. Scale bars, 50 μm.

To test whether Dpp signaling is required for EMT, we generated mosaic clones of the type I receptor thickveins (tkv) using the ELF system. This approach relies on three transgenes, ey3.5-Gal80, lama-Gal4 and UAS-FLP, to generate homozygous mutant somatic clones in the optic lobe, while leaving wild type activity in the eye. Strikingly, tkvstrII mutant neuroepithelial cells formed small ectopic clusters close to the p-Ipc consistent with EMT defects (Fig. 4g-i). dpp-lacZ expression indicated that these clusters originated from the dpp-positive p-Ipc subdomains (Fig. 4g). Failure to repress brk-lacZ (Fig. 4h) and upregulate omb-lacZ (Fig. 4i) confirmed that clusters arose because of a pathway activation defect. This suggests that cells in ventral and dorsal p-Ipc subdomains release Dpp and activate signaling in their own expression domain to promote EMT.

Migratory progenitors set up a new proliferative zone

The Ipc generates two major neuron populations, distal cells and lobula plate neurons6. Using molecular markers, we observed that distal cells express Abnormal chemosensory jump 6 (Acj6) and Twin of Eyeless (Toy), and lobula plate neurons Acj6 and the retinal determination gene network (RDGN) member Dachshund (Dac) (Fig. 5a,b). In the retina, lamina and medulla, neurons processing information from the posterior eye are born first and innervate posterior neuropil areas, while neurons processing increasingly anterior visual input are born later and innervate anterior neuropil areas6. A temporal neurogenesis gradient is thus used for anterior-posterior retinotopic map formation in these ganglia30. Therefore, we assessed a potential correlation between birth order and positions of neuron cell bodies and their projections in d-Ipc progeny. The distribution of EdU labeled cells 5 hours after larval feeding (Fig. 5c), as well as MARCM lineage analysis (Fig. 5e-k) revealed that newborn distal cells were situated between the lamina and d-Ipc, and older progeny in a layer above lobula plate neurons (Fig. 5d-g). Young lobula plate neurons formed columns closest to the d-Ipc on the opposite side, while older neurons were displaced centrally (Fig. 5d,e,h-k). In both neuron populations, somata of the youngest neurons resided next to the d-Ipc and extended neurites into the most anterior part of the proximal medulla or lobula complex neuropils. By contrast, somata of older neurons were located in areas distant from the d-Ipc and extended axons to posterior neuropil sections. Somata and projections of intermediate-aged neurons adopted interim positions. Hence, relative to medulla neurons generated by the medial Opc, the d-Ipc produces progeny in matching spatial and birth-order patterns. Because the Opc is located superficially and the p-Ipc centrally, this suggests that migratory progenitors help to generate a new proliferative niche, resulting in similar positions for d-Ipc and Opc neuroblasts.

Figure 5. d-Ipc progeny are generated in a defined spatio-temporal pattern.

(a,b) The d-Ipc produces two populations, distal cells (dc) and lobula plate neurons (lopn) labeled with abnormal chemosensory jump 6 (acj6)-Gal4, UAS-cd8GFP (green, a). Somata of Twin of eyeless-positive (Toy+) distal cells (red, b) reside in a layer above Dachshund-positive (Dac+) lobula plate neurons (red, a). Distal cell neurites form tracts (arrowhead) between ganglion mother cell (Gmc)-enriched d-Ipc zones adjacent to lamina neurons (ln) and project into the proximal medulla neuropil (arrow, a). Lobula plate neurons extend neurites into the lobula complex neuropils (asterisk, a). The d-Ipc produces Dac (young, y) and Dac and acj6-Gal4 (old, o) expressing progeny (a). (c) In EdU labeling experiments (incorporation for 2.5 hours, dissection after 5 hours), newly born EdU+ lamina neurons and medulla neurons (mn) (red) are added laterally and medially of Opc neuroepithelial cells, respectively. Distal cells and lobula plate neuron columns are added from lower and upper d-Ipc (arrows), respectively. (d) Schematic of locations and simplified projections of young, medium-aged and older Opc and d-Ipc progeny. (e–k) MARCM clones of d-Ipc progeny correlate birth-order and position of somata with their projections (arrowheads) in medulla and lobula complex neuropils (outlined). Clones of newly generated distal cells and lobula plate neurons are situated adjacent to the d-Ipc and extend neurites into anterior neuropil domains (e). Older neurons are shifted laterally and innervate more posterior neuropil domains (f–k). For genotypes and sample numbers, see Supplementary Table 1. Scale bars, 50 μm.

d-Ipc neuroblasts transit through two stages

Do progenitors mature into two distinct neuroblast populations or one population that undergoes a switch in competence? To address this question, we examined the expression patterns of candidate transcription factors, beginning with the proneural proteins Lethal of Scute (L’sc), Ase and Atonal (Ato). In the medial Opc, L’sc is transiently expressed in neuroepithelial cells that next transform into neuroblasts, and mediates the timely onset of neuroblast formation10,11. Unexpectedly, neuroepithelial cells at the inner p-Ipc crescent edge expressed L’sc despite converting into migratory progenitors and not neuroblasts (Fig. 6a). Although used as a general marker for committed neural precursors31, Ase was restricted to Dpn+ neuroblasts and Gmcs in the lower d-Ipc. Extending previous reports18,32 we observed transient Ato expression in upper d-Ipc neuroblasts. These also co-stained with Dac, whose expression persisted in lobula plate neurons (Fig. 6b,c).

Figure 6. Transcription factor expression patterns in d-Ipc neuroblasts.

(a) p-Ipc neuroepithelial cells (arrowhead) adjacent to cell streams express Lethal of scute (L’sc, red). (b,c) Deadpan-positive (Dpn+, blue) d-Ipc neuroblasts (Nb) sequentially express Asense (Ase, red, arrowheads, b), Atonal (Ato, red, arrows, c) and Dachshund (Dac, green, arrows b,c), and solely Dac (double arrowheads, c). (d,e) Dichaete (D, blue) shows strong overlap with Ase (red, arrowheads, d), and weak or no overlap with Ato (red) and Dac (green) in neuroblasts (arrows, e). (f) Progenitors (arrows) and lower d-Ipc neuroblasts (asterisk) express D (blue). Tailless (Tll, red) is expressed in p-Ipc neuroepithelial cells (double arrowheads), upper d-Ipc neuroblasts (arrowheads), ganglion mother cells (Gmc), and young distal cells (dc) and lobula plate neurons (lopn). D and Tll overlap in central neuroblasts (small arrows). (g) The wild type (wt) MARCM clone shows that neuroblasts in the lower d-Ipc give rise to Gmcs orientated towards the lamina (la, arrows), and where distal cells are found. Asterisk indicates an independent lamina glia clone. (h) The clone shows labeling of distal cells, and Ase-negative neuroblasts in the upper d-Ipc, that produce lobula plate neurons. (i) GFP driven by decapentaplegic (dpp)-Gal4 is present in a subset of neuroblasts and persists in both distal cell and lobula plate neuron populations. (j) Summary of expression patterns. For genotypes and sample numbers, see Supplementary Table 1. Scale bars, 50 μm.

D and the orphan nuclear receptor Tailless (Tll) define the last two stages within the Opc-specific temporal cascade13,14. We detected D in progenitors and Ase+ neuroblasts in the lower d-Ipc, and Tll in p-Ipc neuroepithelial cells and upper d-Ipc neuroblasts, as they begin to downregulate Ase and D and upregulate Ato and Dac (Fig. 6d-f). Tll was also expressed in Ase+ Gmcs, and transiently in their progeny and the youngest lobula plate neurons (Fig. 6f).

To assess whether neuroblasts switch from generating distal cells in the lower d-Ipc to lobula plate neurons in the upper d-Ipc, we examined configurations of young wild type MARCM clones (Fig. 6g,h). Clones in the lower d-Ipc (n=2) showed neuroblasts generating Gmcs towards the lamina and thus the area where young distal cells were detected (Fig. 6g; cf. Fig. 5b). In other clones (n=6), both neuron populations were labeled, and Ase– neuroblasts were associated with newborn lobula plate neurons (Fig. 6h), suggesting that after generating distal cells, neuroblasts produced lobula plate neurons. GFP driven by dpp-Gal4 in a neuroblast subset persisted in both neuron populations in a similar configuration as observed with MARCM clones (Fig. 6i). Together, these findings support the notion that d-Ipc neuroblasts transit through two main stages, which are characterized by Ase, and Ato/Dac expression, and correlate with the generation of distal cells and lobula plate neurons at defined positions (Fig. 6j).

L’sc and Ase control neuroblast supply and maturation

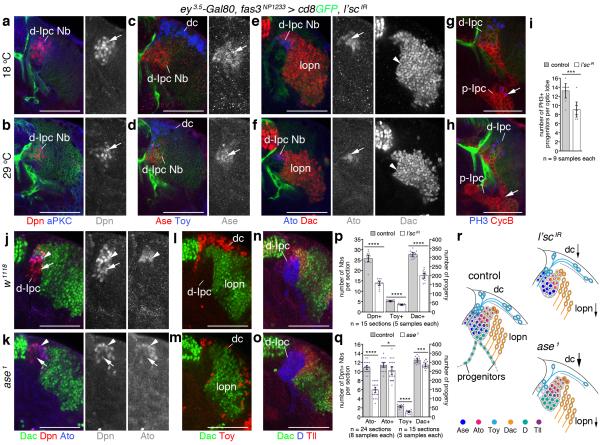

To determine the requirement of l’sc, we used two validated RNAi transgenes for Ipc-specific knockdown (Supplementary Fig. 2a-g). Because l’sc is essential for embryonic optic placode development33, transgene expression was kept low by growing animals at 18°C to bypass early defects in neuroepithelium formation. Controls were maintained at this temperature, whereas experimental animals were shifted to 29°C from the early third instar larval stage until dissection at the wandering stage 48 hours later. Under these conditions, l’sc knockdown did not affect p-Ipc or cell stream formation (Supplementary Fig. 2h-k). d-Ipc neuroblasts expressed Ase and Ato, and their progeny expressed Toy and Dac (Fig. 7a-f), suggesting that neuroblasts were able to transit through the two stages and generate offspring. However, the number of Dpn+ neuroblasts was significantly reduced, and both Ase+ and Ato+ neuroblasts and their progeny were affected (Fig. 7a-f,p). Moreover, ~30% fewer progenitors per optic lobe underwent mitosis at the base of cell streams (Fig. 7g-i). This suggests that l’sc could regulate the supply of progenitors that mature into d-Ipc neuroblasts (Fig. 7r).

Figure 7. Lethal of scute and Asense differentially promote d-Ipc neuroblast supply and maturation.

(a–f) fasciclin3 (fas3)NP1233-Gal4 drives lethal of scute (l’sc) RNAi transgene expression at 18°C (control, a,c,e) and after a shift to 29°C (knockdown, b,d,f). Compared to controls, l’sc knockdown decreases Deadpan-positive (Dpn+) neuroblast (Nb) numbers (red, arrows, a,b). Fewer Asense-positive (Ase+) neuroblasts (red, arrows) and Twin of eyeless-positive (Toy+) distal cells (dc, blue) form (c,d). Fewer Atonal-positive (Ato+) neuroblasts (blue, arrows) and Dachshund-positive (Dac+) progeny (red, arrowheads) arise (e,f). (g,h) Less progenitors in cell streams (arrows) show phosphoHistone 3 (PH3, blue, arrow). (i) Quantification of PH3-positive progenitors per optic lobe in controls and upon l’sc knockdown. (j,k) ase loss decreases Dpn+/Ato– neuroblast numbers (red, arrows). Dpn+/Ato+ (blue) neuroblasts are affected less (arrowheads). (l,m) Toy+ distal cell (red) numbers are reduced; Dac+ progeny (green) are mildly affected. (n,o) Dichaete (D, blue) and Tailless (Tll, red) persist. (p,q) Quantification of l’sc knockdown and ase1 loss-of-function phenotypes. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences. (r) Schematic summarizing observed phenotypes. Arrow sizes indicate the extent of cell loss. D and Tll expression are not shown for l’sc. (i,p,q) Graphs show data point distributions and means ± 95% confidence intervals. Two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test p-values: (i) p=0.0007; (p) p=1.18×10−12; p=1.07×10−12; p=1.95×10−13; (q) p=2.88×10−17; p=0.02; p=2.11×10−11; p=0.0007. t-values and degrees of freedom (df): (i) t=4.16, df=15.96; (p) t=13.71, df=23.32; t=12.41, df=27.12; t=14.29, df=24.68; (q) t=13.65, df=43.17; t=2.44, df=35; t=10.70, df=28; t=3.84, df=27.51. For genotypes and sample numbers, see Supplementary Table 1. Scale bars, 50 μm.

We next examined optic lobes of larvae that were hemizygous for ase1, a viable loss-of-function deletion34. Compared to controls, ~45% less d-Ipc neuroblasts solely expressed Dpn, whereas the number of neuroblasts labeled with Dpn and Ato was only marginally reduced (Fig. 7j,k,q). Consistently, ase loss strongly affected the generation of Toy+ distal cells and mildly that of Dac+ progeny (Fig. 7l,m,q). D and Tll were expressed normally (Fig. 7n,o), confirming that progenitors with the potential to become neuroblasts were present. Hence, progenitors require ase to mature into Dpn-expressing neuroblasts and to generate distal cells (Fig. 7r). However, d-Ipc neuroblasts do not need to pass through the Ase+ stage to express Ato and to produce lobula plate neurons.

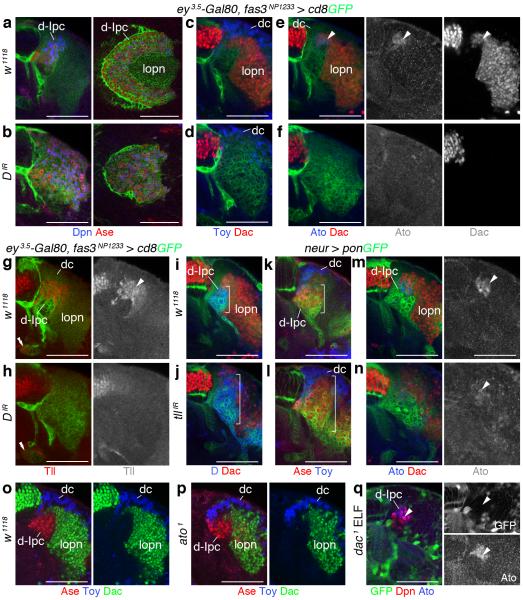

D and Tll control the transition between neuroblast stages

Finally, we asked whether D and Tll could promote the switch to the second neuroblast stage. When knocking down D in the Ipc using two validated RNAi transgenes, Dpn+/Ase+ neuroblasts were generated (Fig. 8a,b and Supplementary Fig. 3). Moreover, within the superficial cell body layer, progeny expressed Toy, indicating that D is not required for distal cell specification (Figs. 8c,d). However, Ato+/Dac+ neuroblasts failed to form, and lobula plate neurons were absent. In consequence, remaining neuroblasts within the d-Ipc were no longer arranged in a crescent but a disk (Fig. 8a-f).

Figure 8. Dichaete acts upstream of Tailless to mediate the transition from Asense-positive to Atonal/Dachshund-positive neuroblasts.

(a–h) Effects of Ipc-specific Dichaete (D) knockdown using fas3NP1233-Gal4 (b,d,f,h) were compared to w1118 controls (a,c,e,g). (a,b) D knockdown does not affect the formation of Deadpan/Ase-positive (Dpn+/Ase+) neuroblasts. Lobula plate neurons (lopn) fail to form. Lateral views in right-hand panels show that the d-Ipc does not form a crescent and instead is disk-shaped. (c-f) Twin of eyeless (Toy+) distal cells (dc) are generated; Atonal/Dachshund-positive (Ato+/Dac+) neuroblasts (arrowheads) and Dac-expressing lobula plate neurons are absent. (g,h) D knockdown leads to complete loss of Tailless (Tll) in d-Ipc neuroblasts (arrowhead) and their progeny. Tll expression in the p-Ipc (double arrowheads) is not affected. (i–n) Effects of tll knockdown using neuralized (neur)-Gal4 in d-Ipc neuroblasts (j,l,n) were compared to w1118 controls (i,k,m). (i,j) Upon tll knockdown, D expression is expanded. (k,l) Ase+ d-Ipc neuroblasts and Toy+ distal cells can form. (m,n) Ato+/Dac+ d-Ipc neuroblasts (arrowheads) and Dac+ neuroblasts and lobula plate neurons are reduced. (o,p) Loss of ato does not interfere with Dac expression. (q) Loss of dac in ELF clones does not interfere with Ato expression. For genotypes and sample numbers, see Supplementary Table 1. Scale bars, 50 μm.

We next examined the cross-regulatory interactions between D and tll. When knocking down D, neuroblasts and their progeny lacked Tll expression (Fig. 8g,h). Since Tll played an early role in p-Ipc formation, we used neuralized-Gal4 (neur-Gal4) to express a validated RNAi transgene in the d-Ipc (Supplementary Fig. 4). tll knockdown expanded the D+ and Ase+ expression domain (Fig. 8i-l). The numbers of Ato-expressing neuroblasts, and consistently of Dac+ neuroblasts and lobula plate neurons were severely reduced (Fig. 8m,n). Their formation was likely not fully abolished because of incomplete knockdown (Supplementary Fig. 4d). d-Ipc neuroblasts in ato1 homozygous mutants continued to express Dac, while mutant neuroblasts in dac1 ELF mosaics maintained Ato, indicating that Ato and Dac are not epistatic to each other (Fig. 8o-q). Loss of ato also did not alter the extent of Ase expression. Hence, D is required to upregulate tll, and tll to repress D and ase. Their cross-regulatory relationship is essential for neuroblasts to switch from Ase to Ato/Dac expression and thus the formation of two distinct neuron populations (Supplementary Fig. 5).

DISCUSSION

Recent studies distinguished three neurogenesis modes in the Drosophila CNS4. First, type I neuroblasts arise from neuroepithelia and generate Gmcs, which produce neuronal and glial progeny. Second, Dpn+ type II neuroblasts in the dorsomedial central brain additionally go through a transit-amplifying Dpn+/Ase+ population, called intermediate neural precursors (Inp), which generate Gmcs and postmitotic offspring35-37. Third, lateral Opc neuroepithelial cells bypass the neuroblast stage and generate Lpcs that divide once to produce lamina neurons15. Our study provides evidence for a fourth strategy: p-Ipc neuroepithelial cells give rise to progenitors that migrate to a second neurogenic domain, where they mature into type I neuroblasts. These progenitors are distinct, because they originate from a neuroepithelium, do not express markers for neuroblasts, Inps, Gmcs or postmitotic neurons, and acquire Nsc properties after completing their migration.

Migratory progenitors arise from the p-Ipc by a mechanism that shares cellular and molecular characteristics with EMT. Based on data of gastrulation and neural crest formation, EMT is commonly associated with cells adopting a mesenchymal state, enabling them to leave their epithelial tissue and migrate through the extracellular matrix to new locations38. A recent study also reported an EMT-like process within the mammalian neocortex, whereby newborn neurons and intermediate progenitors delaminate from the ventricular neuroepithelium and radially migrate to the pial surface39. We observed that neuroepithelial cells at the p-Ipc margins and migratory progenitors upregulated the Snail homolog Esg, whereas E-cad levels decreased. Moreover, esg knockdown caused the formation of ectopic E-cad expressing clusters adjacent to the p-Ipc. While this is a previously uncharacterized role of Drosophila esg, our findings are in line with the requirement of two Snail transcription factors, Scratch1 and 2, and downregulation of E-cad in cortical EMT39.

Although TGFβ signaling is well known to induce EMT25, it was unclear whether it could have such a role in the brain. Two lines of evidence are consistent with a requirement of the Drosophila family member Dpp: (1) it is expressed and downstream signaling is activated in dorsal and ventral p-Ipc subdomains and emerging cell streams; and (2) tkv mutant cells form small neuroepithelial clusters in p-Ipc vicinity. Similar to the neural crest where distinct molecular cascades control delamination in the head and trunk40, region-specific regulators may also be required in p-Ipc subdomains. Because neuroblasts derived from Dpp-dependent cell streams map to defined areas in the d-Ipc, this pathway could potentially couple EMT and neuron subtype specification.

Cell migration is an essential feature of vertebrate brain development. Commonly, postmitotic immature neurons migrate from their proliferation zones to distant regions where they further differentiate and integrate into local circuits. Examples include the radial migration of projection neurons and tangential migration of interneurons in the embryonic cortex, as well as migration of interneuron precursors within the rostral migratory stream to the olfactory bulb in adults5. By contrast, Ipc progenitors develop into Nscs/neuroblasts after they migrated. A recent study described that Nscs relocating from the embryonic ventral hippocampus to the dentate gyrus act as source for adult Nscs in the subgranular zone41. Also, cerebellar granule cell precursors migrate from the rhombic lip to the external granule layer where they proliferate during early postnatal development42. The migration of neural cell types that become proliferative in a new niche could thus constitute a more general strategy. Ipc progenitors form streams of elongated, closely associated cells. Despite their different developmental state, their organization is remarkably similar to the neuronal chain network in the lateral walls of the subventricular zone and the rostral migratory stream in mammals43,44, or of migratory trunk neural crest cells in chick40. Further studies will need to identify the determinants, directing migratory progenitors into the d-Ipc.

Several constraints could shape a neurogenesis mode that requires migratory progenitors within the larval optic lobe. The Opc is located superficially and the Ipc centrally. If medulla and lobula neurons arose by neuroepithelial duplications, these new populations needed to be integrated into an ancestral visual circuit consisting of lamina and lobula plate neurons22. Cellular migration may thus be a derived feature and serve as an essential spatial adjustment of the Ipc to the newly added medulla. In principle, the migratory population could consist of immature neurons. However, migratory progenitors help to establish a new superficial proliferative niche, and to align Opc and d-Ipc neuroblast positions. This in turn enables the Opc and Ipc to use spatially matching birth order-driven neurogenesis patterns for establishing functionally coherent connections across ganglia.

Ipc progenitors are primed to mature into neuroblasts, but are prevented to do so within cell streams. Consistently, progenitors show weak cytoplasmic Mira expression and prematurely differentiate into neuroblasts upon loss of Pcl. While D represses ase to maintain embryonic neuroectodermal cells in an undifferentiated state45, we did not identify such a role in the Ipc. Future studies are thus required to distinguish whether this block in neuroblast maturation is released within the d-Ipc by cell-intrinsic mechanisms or locally acting signals.

The p-Ipc and d-Ipc consecutively express three proneural factors. esg-positive p-Ipc neuroepithelial cells transiently express L’sc as they convert into progenitors. Upon arrival in the d-Ipc, progenitors mature into neuroblasts, which switch bHLH protein expression from Ase to Ato. This correlates with a change in cell division orientations from towards the lamina to the optic lobe surface, and the generation of two lineages, distal cells and lobula plate neurons. The progression of neuroblasts through two stages is supported by the observations that progenitors solely enter the lower d-Ipc, all neuroblasts are labeled with Ase in this area, and dpp reporter gene expression in a progenitor subset persists in both lower and upper d-Ipc neuroblasts and their progeny.

Late l’sc knockdown reduced the number of d-Ipc neuroblasts and both neuron classes, while p-Ipc formation and EMT of progenitors appeared unaffected. This supports the idea that l’sc promotes neuroblast formation by controlling the rate of conversion and thus the progenitor supply. By contrast, ase loss significantly decreased the amount of lower d-Ipc neuroblasts and distal cells. This revealed a central role in the maturation of progenitors into neuroblasts, endowing them with the potential to proliferate and generate a specific lineage. While these functions are opposite of those observed in the Opc46, they align with the role of a murine Ase homolog, Achaete-scute homolog 1 (Ascl1) in the embryonic telencephalon47. To our knowledge, Ase– neuroblasts with type I proliferation patterns have previously not been described. Further underscoring the context-dependent activities of proneural bHLH factors48, ato does not play the equivalent role of ase in conferring neurogenic properties to upper d-Ipc neuroblasts, but acts upstream of differentiation programs controlling the projections of lobula plate neurons18.

While Ase and Ato each regulate distinct aspects of d-Ipc development, they are neither required for the transition nor the extent of their expression domains. These roles are played by D and tll, whose cross-regulatory interactions are essential for the transition from Ase+ to Ato+/Dac+ expression. To link birth order and fate temporal identity transcription factors are sequentially expressed by neuroblasts and inherited by Gmcs and their progeny born during a given developmental window49. Acting as the final two members of the Opc-specific series of temporal identity factors, D is required for Tll expression, while tll is sufficient but not required to inhibit D13. While Opc and d-Ipc neuroblasts share the sequential expression of D and Tll, key differences include that (1) d-Ipc progeny do not maintain D; (2) Tll is transiently expressed in newborn progeny of the upper d-Ipc and not maintained in older lineages; (3) D in the lower d-Ipc is not required in its own expression domain for neurogenesis; and (4) D is required to activate tll, and tll to repress D and ase, as well as to independently upregulate Ato and Dac. While the mechanisms that trigger the timing of the switch require further analysis, these observations support the notion, that in the d-Ipc, D and tll do not function as temporal identity factors, but as switching factors between two sequential neuroblast stages. The vertebrate homologs of D and tll, Sox2 and Tlx are essential for adult Nsc maintenance and Sox2 positively regulates Tlx expression50, suggesting that core regulatory interactions between D and tll family members may be conserved.

Our studies uncovered molecular signatures for generating a migratory neural population by EMT and subsequent Nsc development that are in part shared between the fly optic lobe and vertebrate cortical neurogenesis. The unexpected parallels suggest that ancestral gene regulatory cassettes imparting specific cellular properties may have been re-employed during vertebrate brain development. Analysis of p-Ipc/d-Ipc neurogenesis in the Drosophila optic lobe therefore opens new possibilities to systematically identify genes regulating EMT, cell migration, and sequential Nsc specification.

METHODS

Genetics

Drosophila melanogaster strains were maintained in standard medium at 25°C except for RNAi experiments, for which progeny were shifted to 29°C at 24 hours after egg laying (AEL). The following stocks/crosses were used for: (i) Expression analyses - (1) dpp-lacZExel.2; (2) esg-lacZB7-2-22 (ref. 51); (3) acj6-Gal4 UAS-cd8GFP/FM7c; PinYT/CyO (from G. Jefferis, ref. 52); (4) esgMH766-Gal4 (this study) crossed to (5) PinYT/CyO; UAS-cd8GFP; (6) brkx47 × UAS-cd8GFP; dppblk1-Gal4/TM6b (ref. 53); (7) ombP1 × UAS-cd8GFP; dppblk1-Gal4/TM6b (ref. 54). The Mill Hill (MH)-Gal4 line esgMH766-Gal4 was generated in an enhancer trap Gal4 screen to identify drivers with restricted activity in the visual system. Inverse PCR determined the P element insertion site as 364 bp upstream of escargot (esg) (chromosome 2L: bp 15,333,500). (ii) Loss-of-function analysis using the ey3.5-Gal80, lama-Gal4, UAS-FLP (ELF) system55,56 - (1) ELF 2L: y w ey3.5-Gal80; ubi-GFP cycEAR95 FRT40A/Gla Bc; lama-Gal4 UAS-FLP mδ crossed to (2) y w; FRT40A, (3) tkvstrII FRT40A/Gla Bc, (4) y w; FRT40A; dpp-lacZExel.2, (5) tkvstrII FRT40A/Gla Bc; dpp-lacZExel.2, (6) ombP1; FRT40A; TM2/TM6B, (7) ombP1; tkvstrII FRT40A/Gla Bc, (8) brkx47; FRT40A; TM2/TM6B, (9) brkx47; tkvstrII FRT40A/Gla Bc; TM2/TM6B, (10) dac1 FRT40A/CyO [3, 5, 7, 9, tkvstrII allele (ref. 57); 10, dac1 from F. Pignoni]. (iii) Lineage and loss-of-function analysis using mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM)23 - (1) w hs-FLP122 elav-Gal4c155 UAS-cd8GFP; FRT42D tubP-Gal80/CyO crossed to (2) y w, FRT42D; (3) y w; FRT42D; tubP-Gal4/TM6B, (4) y w; FRT42D Pcl3-78*38/Gla Bc; tubP-Gal4/TM6B (Pcl3-78*38, H.A, I.S. unpublished allele). 24 hour embryo collections were heat shocked for 40–60 min at 24–48 or 48–72 hours AEL in a 37°C water bath. (iv) Knockdown experiments using UAS-RNAi transgenes - (1) y w ey3.5-Gal80; fas3NP1233-Gal4; UAS-Dcr2 UAS-cd8GFP/TM6B crossed to (2) w1118, (3) UAS-fas3IR KK100642, (4) UAS-esgIR GD9794, (5) UAS-esgIR TRiP.JF03134, (6) UAS-l’scIR TRiP.JF02399, (7) UAS-l’scIR KK104691, (8) UAS-DIR KK107194, (9) UAS-DIR GD49549, (10) UAS-tllIR GD6236; (11) w; neurP72-Gal4 (ref. 58), UAS-pon-GFP/TM6B crossed to (12) w1118, (13) UAS-tllIR GD6236; UAS-Dcr2. UAS-l’scIR experimental animals were grown at 18°C and shifted to 29°C at the early third instar larval stage. UAS-l’scIR control animals were maintained at 18°C. (v) Hemizygous and homozygous viable mutant alleles, respectively - (1) Df(1)ase-1, scase-1 pn1/C(1)DX, y1 f1 (ref. 34,59); (2) ato1 (ref. 60). In ELF mosaics, clones lack GFP, while in MARCM mosaics clones are labeled with GFP. If not otherwise indicated, stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center and are described in FlyBase. Generally, crosses involved about 5 males and 7 unfertilized females. To avoid overcrowding, parents were transferred to fresh vials every day or every second day.

Immunolabeling

Brains were dissected in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed for 1 hour at room temperature in 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M L-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich) containing 0.05 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and washed in PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich). The following primary antibodies were used for immunolabeling: rabbit anti-Ase (1:5000, from Y.N. Jan, ref. 31), rabbit anti-Ato (1:5000, from Y.N. Jan), mouse anti-CycB (F2F4, 1:5, DSHB), mouse anti-Dac (mAbdac2-3, 1:50, DSHB), rat anti-E-cad (DCAD2, 1:2, DSHB), mouse anti-Discs large (4F3, 1:50, DSHB), guinea pig anti-Dpn (1:500, from J. Skeath, ref. 61), guinea pig anti-D (1:200, from A. Gould, ref. 62), rat anti-Elav (1:25, DSHB), mouse anti-Fas3 (7G10, 1:5, DSHB; ref.63-65), mouse and rabbit anti-β-galactosidase (1:300, Promega #Z3783; 1:12,000, Cappel #559762), rabbit anti-Insc (1:200, ref.66), rabbit anti-L’sc (1:800, from A. Carmena), mouse anti-Mira (PLF81, 1:50, ref.67), rabbit anti-PH3 (1:100, Millipore/Upstate #06-570), rabbit anti-aPKC ζ (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies #sc-216, ref. 68), mouse anti-Pros (MR1A, 1:50, DSHB, ref. 69), guinea pig anti-Toy (1.170, 1:200, from U. Walldorf), and rabbit anti-Tll (812, 1:100, J. Reinitz segmentation antibodies70). For immunofluorescence labeling, the following secondary antibodies were used: goat anti-guinea pig, anti-mouse, anti-rabbit, and anti-rat F(ab’)2 fragments coupled to FITC, Cy3 or Cy5 (1:400; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Optic lobes with a similarly sized lamina were used to compare control and experimental samples of the same age.

EdU labeling

For EdU labeling, dissected third instar larval brains were incubated for 1 hour in 10 μM EdU (Click-iT™ EdU Imaging Kit, Invitrogen) in PBS, fixed as described above, washed in PBS, and visualized by detection with Alexa Fluor azide 594. For EdU pulse-chase experiments, wandering third instar larvae were transferred onto small grape-juice plates with standard cornmeal agar supplemented with 1.3 ml EdU/PBS (1.5 mM). After 2.5 hours of feeding, larvae were transferred onto standard food. Brains were dissected immediately (0 hour), or after 1, 2 and 5 hours, and in a separate experiment after 4 hours. As EdU incorporation depends on feeding behavior, which declines in wandering larvae, younger larvae fed with EdU had a higher success rate of incorporation than older ones: 21% (n = 28) larvae dissected after 0 hours incorporated EdU, 30% (n = 73) after 1 hour, 69% (n = 39) after 2 hours, and 89% (n = 28) after 5 hours.

Generation of 3D model

Optic lobes of esg-Gal4MH766/+; UAS-cd8GFP/+ third instar larvae were dissected and labeled with Ase and E-cad. The optic lobe used for generating the 3D model (Fig. 1l) was mounted in a horizontal orientation. 426 optical sections at 0.5 μm intervals were collected with a confocal laser microscope. ImageJ was used to generate a stack of Tiff files, which were imported into the open source program Fiji/TrakEM2. This software has been designed for reconstructing serial electron micrographs, but can be adapted to manually outline and trace specific areas throughout a stack of optical sections71. For the model, the following areas were reconstructed: Opc neuroepithelium, lamina, medulla neuroblasts and Gmcs, p-Ipc neuroepithelium, progenitor cell streams, d-Ipc neuroblasts and Gmcs, as well as s-Ipc neuroblasts, Gmcs, neuronal progenitors and extending neurite tracts. The resulting segmented objects were assembled into a model using the Fiji 3D viewer.

Quantifications

To quantify numbers of neuroblasts and Dac+ and Toy+ progeny in animals expressing UAS-l’scIR in the Ipc, experimental animals were shifted to 29°C at the early third instar larval stage and dissected at the late third instar larval stage. Control animals were kept at 18°C. Optic lobes were imaged in horizontal orientations and cell numbers were collected from three serial optical sections per sample (6-μm distance) at the d-Ipc center. Similarly, numbers of Dpn+/Ato– and Dpn+/Ato+ neuroblasts, as well as Dac+ and Toy+ progeny in ase1 hemizygous experimental and w1118 control animals were collected from three optical sections per sample (6-μm distance), imaged in horizontal orientation at the d-Ipc center. If not otherwise indicated, the penetrance of observed phenotypes was 100% for examined samples.

Statistics

Sample sizes were not predetermined by statistical calculations, but were based on the standard of the field. In a pool of control or experimental animals, specimens of the correct stage and genotype were selected randomly and independently from different vials. Data acquisition and analysis were not performed blindly. They relied on samples with identified genotypes and are therefore not limited in repeatability. The calculation of 95% confidence interval error bars and unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test p-values were performed using Microsoft Excel [Confidence.T and T.Test (type 3, not assuming equal variance)]. Prism 6 GraphPad was used to perform Shapiro-Wilk and D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality tests. Data met the assumption of normality in one or both tests. Because of the presence of a single outlier point in three of the data sets in Fig. 7i and p, quantifications are presented as scatter plots and bar graphs. t-values and degrees of freedom were determined with the help of Prism 6 GraphPad (Welch-corrected, not assuming equal standard deviations). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; **** P < 0.0001.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Baena-Lopez, A. Carmena, A. Gould, Y.N. Jan, H. Jäckle, A. Jarman, G.X.S Jefferis, J. Mueller, J. Skeath, R. Sousa-Nunes, E. Piddini, F. Pignoni, J.P. Vincent, U. Walldorf, the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (NIH P40OD018537), the Drosophila Genomics Resource Center, the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for fly strains and antibodies. We thank A. Alifandi for help with EdU feeding experiments, A. Bailey and C. Desplan for helpful discussions, and A. Baena-Lopez, F. Guillemot, E. Ober, J.P. Vincent, B. Richier and N. Shimosako for critical reading of the manuscript. This work is supported by the Medical Research Council (U117581332).

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

A Supplementary Methods Checklist is available.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lui JH, Hansen DV, Kriegstein AR. Development and evolution of the human neocortex. Cell. 2011;146:18–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Florio M, Huttner WB. Neural progenitors, neurogenesis and the evolution of the neocortex. Development. 2014;141:2182–2194. doi: 10.1242/dev.090571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brand AH, Livesey FJ. Neural stem cell biology in vertebrates and invertebrates: more alike than different? Neuron. 2011;70:719–729. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Homem CC, Knoblich JA. Drosophila neuroblasts: a model for stem cell biology. Development. 2012;139:4297–4310. doi: 10.1242/dev.080515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayala R, Shu T, Tsai LH. Trekking across the brain: the journey of neuronal migration. Cell. 2007;128:29–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hofbauer A, Campos-Ortega JA. Proliferation and and early differentiation of the optic lobes in Drosophila melanogaster. Roux’s Arch. Dev. Biol. 1990;198:264–274. doi: 10.1007/BF00377393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischbach KF, Dittrich APM. The optic lobe of Drosophila melanogaster. I. A Golgi analysis of wild-type structure. Cell Tissue Res. 1989;258:441–475. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green P, Hartenstein AY, Hartenstein V. The embryonic development of the Drosophila visual system. Cell Tissue Res. 1993;273:583–598. doi: 10.1007/BF00333712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egger B, Boone JQ, Stevens NR, Brand AH, Doe CQ. Regulation of spindle orientation and neural stem cell fate in the Drosophila optic lobe. Neural Dev. 2007;2:1. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yasugi T, Umetsu D, Murakami S, Sato M, Tabata T. Drosophila optic lobe neuroblasts triggered by a wave of proneural gene expression that is negatively regulated by JAK/STAT. Development. 2008;135:1471–1480. doi: 10.1242/dev.019117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egger B, Gold KS, Brand AH. Notch regulates the switch from symmetric to asymmetric neural stem cell division in the Drosophila optic lobe. Development. 2010;137:2981–2987. doi: 10.1242/dev.051250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Apitz H, Salecker I. A challenge of numbers and diversity: neurogenesis in the Drosophila optic lobe. J. Neurogenet. 2014;28:233–249. doi: 10.3109/01677063.2014.922558. doi. 10.3109/01677063.01672014.01922558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X, et al. Temporal patterning of Drosophila medulla neuroblasts controls neural fates. Nature. 2013;498:456–462. doi: 10.1038/nature12319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suzuki T, Kaido M, Takayama R, Sato M. A temporal mechanism that produces neuronal diversity in the Drosophila visual center. Dev. Biol. 2013;380:12–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang Z, Kunes S. Hedgehog, transmitted along retinal axons, triggers neurogenesis in the developing visual centers of the Drosophila brain. Cell. 1996;86:411–422. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang Z, Shilo BZ, Kunes S. A retinal axon fascicle uses spitz, an EGF receptor ligand, to construct a synaptic cartridge in the brain of Drosophila. Cell. 1998;95:693–703. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81639-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meinertzhagen IA, Hanson TE. The development of the optic lobe. In: Bate M, Martinez Arias A, editors. The development of Drosophila melanogaster. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 1363–1491. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oliva C, et al. Proper connectivity of Drosophila motion detector neurons requires Atonal function in progenitor cells. Neural Dev. 2014;9:4. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-9-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maisak MS, et al. A directional tuning map of Drosophila elementary motion detectors. Nature. 2013;500:212–216. doi: 10.1038/nature12320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuthill JC, Nern A, Holtz SL, Rubin GM, Reiser MB. Contributions of the 12 neuron classes in the fly lamina to motion vision. Neuron. 2013;79:128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harzsch S, Walossek D. Neurogenesis in the developing visual system of the branchiopod crustacean Triops longicaudatus (LeConte, 1846): corresponding patterns of compound-eye formation in Crustacea and Insecta? Dev. Genes Evol. 2001;211:37–43. doi: 10.1007/s004270000113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strausfeld NJ. The evolution of crustacean and insect optic lobes and the origins of chiasmata. Arthropod Structure and Development. 2005;34:235–256. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee T, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron. 1999;22:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lanzuolo C, Orlando V. Memories from the polycomb group proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2012;46:561–589. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whiteley M, Noguchi PD, Sensabaugh SM, Odenwald WF, Kassis JA. The Drosophila gene escargot encodes a zinc finger motif found in snail-related genes. Mech. Dev. 1992;36:117–127. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(92)90063-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burstyn-Cohen T, Kalcheim C. Association between the cell cycle and neural crest delamination through specific regulation of G1/S transition. Dev. Cell. 2002;3:383–395. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00221-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heldin CH, Landstrom M, Moustakas A. Mechanism of TGF-beta signaling to growth arrest, apoptosis, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009;21:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Affolter M, Basler K. The Decapentaplegic morphogen gradient: from pattern formation to growth regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007;8:663–674. doi: 10.1038/nrg2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clandinin TR, Feldheim DA. Making a visual map: mechanisms and molecules. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2009;19:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brand M, Jarman AP, Jan LY, Jan YN. asense is a Drosophila neural precursor gene and is capable of initiating sense organ formation. Development. 1993;119:1–17. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.Supplement.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hassan BA, et al. atonal regulates neurite arborization but does not act as a proneural gene in the Drosophila brain. Neuron. 2000;25:549–561. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Younossi-Hartenstein A, Nassif C, Green P, Hartenstein V. Early neurogenesis of the Drosophila brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 1996;370:313–329. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960701)370:3<313::AID-CNE3>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gonzalez F, Romani S, Cubas P, Modolell J, Campuzano S. Molecular analysis of the asense gene, a member of the achaete-scute complex of Drosophila melanogaster, and its novel role in optic lobe development. EMBO J. 1989;8:3553–3562. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bello BC, Izergina N, Caussinus E, Reichert H. Amplification of neural stem cell proliferation by intermediate progenitor cells in Drosophila brain development. Neural Dev. 2008;3:5. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boone JQ, Doe CQ. Identification of Drosophila type II neuroblast lineages containing transit amplifying ganglion mother cells. Dev. Neurobiol. 2008;68:1185–1195. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bowman SK, et al. The tumor suppressors Brat and Numb regulate transit-amplifying neuroblast lineages in Drosophila. Dev. Cell. 2008;14:535–546. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hay ED. The mesenchymal cell, its role in the embryo, and the remarkable signaling mechanisms that create it. Dev. Dyn. 2005;233:706–720. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Itoh Y, et al. Scratch regulates neuronal migration onset via an epithelial-mesenchymal transition-like mechanism. Nat. Neurosci. 2013;16:416–425. doi: 10.1038/nn.3336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Theveneau E, Mayor R. Neural crest delamination and migration: from epithelium- to-mesenchyme transition to collective cell migration. Dev. Biol. 2012;366:34–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li G, Fang L, Fernandez G, Pleasure SJ. The ventral hippocampus is the embryonic origin for adult neural stem cells in the dentate gyrus. Neuron. 2013;78:658–672. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Machold R, Klein C, Fishell G. Genes expressed in Atoh1 neuronal lineages arising from the r1/isthmus rhombic lip. Gene Expr. Patterns. 2011;11:349–359. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lois C, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Chain migration of neuronal precursors. Science. 1996;271:978–981. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doetsch F, Alvarez-Buylla A. Network of tangential pathways for neuronal migration in adult mammalian brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:14895–14900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shen SP, Aleksic J, Russell S. Identifying targets of the Sox domain protein Dichaete in the Drosophila CNS via targeted expression of dominant negative proteins. BMC Dev. Biol. 2013;13:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-13-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wallace K, Liu TH, Vaessin H. The pan-neural bHLH proteins DEADPAN and ASENSE regulate mitotic activity and cdk inhibitor dacapo expression in the Drosophila larval optic lobes. Genesis. 2000;26:77–85. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1526-968x(200001)26:1<77::aid-gene10>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Castro DS, et al. A novel function of the proneural factor Ascl1 in progenitor proliferation identified by genome-wide characterization of its targets. Genes Dev. 2011;25:930–945. doi: 10.1101/gad.627811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bertrand N, Castro DS, Guillemot F. Proneural genes and the specification of neural cell types. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;3:517–530. doi: 10.1038/nrn874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kohwi M, Doe CQ. Temporal fate specification and neural progenitor competence during development. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013;14:823–838. doi: 10.1038/nrn3618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shimozaki K, et al. SRY-box-containing gene 2 regulation of nuclear receptor tailless (Tlx) transcription in adult neural stem cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:5969–5978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.290403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Samakovlis C, et al. Genetic control of epithelial tube fusion during Drosophila tracheal development. Development. 1996;122:3531–3536. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.11.3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bourbon HM, et al. A P-insertion screen identifying novel X-linked essential genes in Drosophila. Mech. Dev. 2002;110:71–83. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00566-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Campbell G, Tomlinson A. Transducing the Dpp morphogen gradient in the wing of Drosophila: regulation of Dpp targets by brinker. Cell. 1999;96:553–562. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80659-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsai SF, et al. Gypsy retrotransposon as a tool for the in vivo analysis of the regulatory region of the optomotor-blind gene in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:3837–3841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chotard C, Leung W, Salecker I. glial cells missing and gcm2 cell autonomously regulate both glial and neuronal development in the visual system of Drosophila. Neuron. 2005;48:237–251. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bazigou E, et al. Anterograde Jelly belly and Alk receptor tyrosine kinase signaling mediates retinal axon targeting in Drosophila. Cell. 2007;128:961–975. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nellen D, Affolter M, Basler K. Receptor serine/threonine kinases implicated in the control of Drosophila body pattern by decapentaplegic. Cell. 1994;78:225–237. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90293-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bellaiche Y, Gho M, Kaltschmidt JA, Brand AH, Schweisguth F. Frizzled regulates localization of cell-fate determinants and mitotic spindle rotation during asymmetric cell division. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:50–57. doi: 10.1038/35050558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jarman AP, Brand M, Jan LY, Jan YN. The regulation and function of the helix-loop-helix gene, asense, in Drosophila neural precursors. Development. 1993;119:19–29. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.Supplement.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jarman AP, Grell EH, Ackerman L, Jan LY, Jan YN. Atonal is the proneural gene for Drosophila photoreceptors. Nature. 1994;369:398–400. doi: 10.1038/369398a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bier E, Vaessin H, Younger-Shepherd S, Jan LY, Jan YN. deadpan, an essential pan-neural gene in Drosophila, encodes a helix-loop-helix protein similar to the hairy gene product. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2137–2151. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.11.2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Russell SR, Sanchez-Soriano N, Wright CR, Ashburner M. The Dichaete gene of Drosophila melanogaster encodes a SOX-domain protein required for embryonic segmentation. Development. 1996;122:3669–3676. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.11.3669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Patel NH, Snow PM, Goodman CS. Characterization and cloning of fasciclin III: a glycoprotein expressed on a subset of neurons and axon pathways in Drosophila. Cell. 1987;48:975–988. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90706-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tayler TD, Robichaux MB, Garrity PA. Compartmentalization of visual centers in the Drosophila brain requires Slit and Robo proteins. Development. 2004;131:5935–5945. doi: 10.1242/dev.01465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hayden MA, Akong K, Peifer M. Novel roles for APC family members and Wingless/Wnt signaling during Drosophila brain development. Dev. Biol. 2007;305:358–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kraut R, Campos-Ortega JA. inscuteable, a neural precursor gene of Drosophila, encodes a candidate for a cytoskeleton adaptor protein. Dev. Biol. 1996;174:65–81. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ohshiro T, Yagami T, Zhang C, Matsuzaki F. Role of cortical tumour-suppressor proteins in asymmetric division of Drosophila neuroblast. Nature. 2000;408:593–596. doi: 10.1038/35046087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wodarz A, Ramrath A, Grimm A, Knust E. Drosophila atypical protein kinase C associates with Bazooka and controls polarity of epithelia and neuroblasts. J. Cell Biol. 2000;150:1361–1374. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.6.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Spana EP, Doe CQ. The prospero transcription factor is asymmetrically localized to the cell cortex during neuroblast mitosis in Drosophila. Development. 1995;121:3187–3195. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.10.3187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kosman D, Small S, Reinitz J. Rapid preparation of a panel of polyclonal antibodies to Drosophila segmentation proteins. Dev. Genes Evol. 1998;208:290–294. doi: 10.1007/s004270050184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cardona A, et al. An integrated micro- and macroarchitectural analysis of the Drosophila brain by computer-assisted serial section electron microscopy. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.