Abstract

The CRISPR-Cas9 system, naturally a defense mechanism in prokaryotes, has been repurposed as an RNA-guided DNA targeting platform. It has been widely used for genome editing and transcriptome modulation, and has shown great promise in correcting mutations in human genetic diseases. Off-target effects are a critical issue for all of these applications. Here we review the current status on the target specificity of the CRISPR-Cas9 system.

Keywords: CRISPR, Cas9, target specificity, off-targets, genome engineering

The CRISPR-Cas9 System

The CRISPR-Cas system is widely found in bacterial and archaeal genomes as a defense mechanism against invading viruses and plasmids [1–6]. The type II CRISPR-Cas system from Streptococcus pyogenes relies on only one protein, the nuclease Cas9, and two noncoding RNAs, crRNA and tracrRNA, to target DNA [7]. These two noncoding RNAs can further be fused into one single guide RNA (sgRNA). The Cas9/sgRNA complex binds double-stranded DNA sequences that contain a sequence match to the first 17-20 nucleotides of the sgRNA if the target sequence is followed by a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) (Figure 1). Once bound, two independent nuclease domains in Cas9 will each cleave one of the DNA strands 3 bases upstream of the PAM, leaving a blunt end DNA double stranded break (DSB). DSBs can be repaired mainly through either the nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway or homology-directed repair (HDR). NHEJ typically leads to short insertion/deletion (indels) near the cutting site, whereas HDR can be used to introduce specific sequences into the cutting site if exogenous template DNA is provided. This discovery paved the way for use of Cas9 as a genome-engineering tool in other species. In this review, we focus on target specificity of the CRISPR-Cas9 system. We refer readers to other excellent reviews for further discussion of the CRISPR-Cas9 technology [8–11].

Figure 1. The CRISPR-Cas9 system.

The sgRNA (purple) targets the Cas9 protein to genomic sites containing sequences complementary to the 5′ end of the sgRNA. The target DNA sequence needs to be followed by a proto-spacer adjacent motif (PAM), typically NGG. Cas9 is a DNA endonuclease with two active domains (red triangles) cleaving each of the two DNA strands three nucleotides upstream of the PAM. The five nucleotides upstream of the PAM are defined as the seed region for target recognition.

Applications of CRISPR-Cas9

Genome editing

The use of the CRISPR-Cas9 system as a tool to manipulate the genome was first demonstrated in 2013 in mammalian cells [12,13]. Both studies showed that expressing a codon-optimized Cas9 protein and a guide RNA leads to efficient cleavage and short indels of target loci, which could inactivate protein-coding genes by inducing frameshifts. Up to five genes have been mutated simultaneously in mouse and fish cells by delivering five guide RNAs [14,15]. Targeting two sites on the same chromosome can be used to create deletions and inversions of regions range from 100 bps to 1000000 bps [16,17]. Defined interchromosomal translocation such as those found in specific cancers can be created by targeting Cas9 to different chromosomes [18]. With exogenous template oligos, specific sequences such as HA-tag or GFP could be inserted into genes to label proteins [19,20], or to correct mutations in disease genes in human and mouse [21–23]. The system has also been adapted to many other species, including monkey, pig, rat, zebrafish, worm, yeast, and several plants [9].

Transcriptome modulation

Mutating the two nuclease domains of Cas9 generates the catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9), or nuclease-null Cas9, which can bind DNA without introducing cleavage or mutation [7]. When targeted to promoters, dCas9 binding alone can interfere with transcription initiation, likely by blocking binding of transcription factors or RNA polymerases. When targeted to the non-template strand within the gene body, dCas9 complex blocks RNA polymerase II transcription elongation [24–26]. Fusing dCas9 with transcription repressor domains such as the Krueppel-associated box (KRAB) leads to stronger silencing of mammalian genes, a technology termed CRISPRi [24]. Activation of transcription is also possible by fusing dCas9 with activator domains such as VP64. However, several studies showed that multiple sgRNAs targeting the same promoter need to be used simultaneously to change target gene expression substantially [27–29]. The position of target sites with respective to transcription start site (TSS) affects the efficiency of silencing or activation, a subject that needs to be further investigated for optimal target design [30].

Genomic loci imaging and other applications

To enable site-specific labeling and imaging of endogenous loci in living cells, GFP has also been fused to dCas9 [31]. In this case, tens of sgRNAs are required to target the same locus such that individual loci show up as punctate dots, unless the target locus contains targetable tandem repeats. The fusion of dCas9 with other heterologous effector domains could enable many other applications. For example, one could fuse dCas9 with chromatin modifiers to change the epigenetic state of a locus. Other potential applications of the system have been previously reviewed extensively [8,9].

Assessing Cas9 Target Specificity

The original characterization of the Cas9/sgRNA system showed that not every position in the guide RNA needs to match the target DNA, suggesting the existence of off-target sites [7]. Concerns about off-target effects depend on the purpose of the targeting. As discussed above and below, Cas9/sgRNA binding at a site does not necessarily lead to DNA cutting or mutation, and binding or cutting may not have any functional consequence either, especially when the off-target sites are outside of genes or regulatory elements. The off-target effects of Cas9 cutting/mutation have been studied extensively but sensitive and unbiased genome-wide characterization is still missing. Below we review existing approaches that have been or can be used to study Cas9 target specificity.

Assay of predicted off-targets

Typically a list of potential off-target sites are predicted based on sequence homology to the on-target, or using more sophisticated tools that incorporate various rules previously described in literature (see section “Tools for target design and off-target prediction”). Two types of assays are commonly used to detect and quantify indels formed at those selected sites: mismatch-detection nuclease assay and next generation sequencing (NGS). In the mismatch-detection nuclease assay, genomic DNA from cells treated with Cas9 and sgRNA is PCR amplified, denatured and rehybridized to form hetero-duplex DNA, containing one wildtype strand and one strand with indels. Mismatches can be recognized and cleaved by mismatch detection nucleases, such as Surveyor nuclease [32] or T7 endonuclease I [33], enabling quantitation of the products by electrophoresis. It is challenging to use this assay to detect loci with less than 1% indels and this assay is difficult to scale-up. Alternatively, the PCR product can also be sequenced directly using NGS platform. The fraction of reads with indels is quantified after mapping to the genome or directly to the amplicon. When combined with proper controls and statistical models, NGS based approaches are more accurate and sensitive than nuclease based assays.

Systematic mutagenesis

To characterize Cas9/sgRNA specificity, several groups performed systematic mutagenic analysis of the sgRNA or target DNA to evaluate the importance of the position, identity, and number of mismatches in the RNA/DNA duplex [12,34,35]. These studies revealed a very complicated picture of Cas9 specificity [36]. However, it is unclear whether the observed variation truly reflects specificity requirement, or is confounded by unintended changes caused by the mutations introduced in the sgRNA or target DNA. For example, mutations in the sgRNA could change the sgRNA abundance dramatically, which would alter the targeting efficiency [37]. Also mutations in DNA might create or disrupt binding sites for endogenous proteins that interfere with Cas9 binding. The number of variants evaluated is also limited in these studies. Finally, each study typically examines less than four target sites, leaving questions whether the observations can be generalized.

In vitro cleavage site selection

A more comprehensive way to study Cas9 cutting specificity is in vitro selection. In this assay a large pool of partially randomized targets are synthesized and cleaved by Cas9 or other nucleases in vitro [38–40]. The cleavage leaves a 5′ phosphate group in the DNA, which can then be ligated to an adaptor and selectively amplified using PCR. The advantages of this approach are that the sequence space explored by the target library can be very large (1012 molecules, even larger than all possible sites in any genome), and that target specificity can be evaluated independently of genome or species used and is not affected by chromatin structure that is usually cell-type specific. However these advantages also impose potential limitations of this assay. Although the sequence space of the library can be huge, most substrates contain on average only 4-5 mismatches to the on-target [38]. Given that efficient cleavage with 7 mismatches has been observed [7], such an assay could still miss a significant fraction of genomic off-targets. For example, when the in vitro cleavage site selection approach was applied to another type of nuclease, the Zinc Finger Nuclease (ZFN), only one of the four off-targets identified by an in vivo assay was detected [40–42]. Alternatively, instead of using partially randomized synthetic DNA library, one could perform the same assay with genomic DNA to detect possible genomic off-targets.

It has also been reported that compared to in vivo conditions, Cas9 cutting is more promiscuous in vitro [43], i.e. off-targets are cleaved at much higher frequency in vitro than in vivo. This can be potentially explained by chromatin blockage of accessibility of the off-target sites in vivo [37,44,45]. Therefore a potential solution is to perform in vitro selection assay using native or fixed chromatin prepared from cells. However, the higher rate of off-target cutting could also be due to higher effective concentrations of Cas9/sgRNA used in vitro. A titration series of Cas9/sgRNA concentration is needed to assess the in vivo relevance of off-target sites identified by in vitro approaches.

DSB capture and sequencing

Cas9 and other DNA endonucleases typically induce DSBs, and several assays have been developed to capture DSBs induced in cells [41,46,47], although none of them have been applied to the Cas9 system. Gabriel et al. transformed human cells with integrase-defective lentiviral vectors (IDLVs), which are incorporated into DSBs via NHEJ pathway, thus tagging those transient cutting events [41]. This approach uncovered four in vivo off-target cleavage sites for a ZFN targeting the CCR5 locus. In another in situ assay called BLESS [47], cells are fixed first and then chromatin is purified and ligated with biotinylated DNA linkers. Both approaches could in principle be applied to Cas9 treated cells to uncover genome-wide cutting sites. Compared to in vitro cleavage site selection approaches, DSB capture approaches are physiologically more relevant, but can be less efficient since most DSBs exist very transiently, and the capture can be biased since both in vivo IDLV labeling and in situ linker ligation can be affected by local chromatin and sequence composition near the cutting site. Thus certain DSBs induced by the nuclease will not be tagged. For instance, of the 36 ZFN off-target sites identified by in vitro selection approach, only one is identified by the IDLV-based DSB capture [42]. In addition, DSB capture approaches may identify large number of false positive sites, since DSBs can be generated by endogenous cellular process independent of Cas9 cutting, or during the library preparation process. Proper controls, such as cells treated with no Cas9 or no sgRNA can be used to filter false positives.

Whole genome sequencing

Compared to assays described above, whole genome sequencing (WGS) would be a less biased assessment of off-target mutations caused by Cas9, although it will miss off-target sites that are bound without cutting, or are cut but then always perfectly repaired. In addition to small indels, WGS can also detect Cas9 induced structural changes, such as inversions [16]. So far relatively high coverage (30-60×) of WGS has been performed in single clones of Cas9 treated cells in a variety of species, including worm [48], Arabidopsis [49], rice [50], and human pluripotent stem cells [51,52]. Interestingly, although a number of mutations were identified in Cas9 treated clones, none were found to be near sites with sequences similar to the target, indicating Cas9 induced off-target mutations are rare and it is possible to obtain clones without off-target mutations. However, due to the high cost, only a few clones have been sequenced for each target, which would miss most low-frequency off-target events. For example, if there was a single possible off-target site per genome mutated at a 40% frequency relative to the on-target site, this could have escaped detection in these experiments. However, if there were 10 possible off-target sites per genome mutated at a 40% frequency, then at least one of these sites should have been detected. Therefore, WGS is ideal for screening individual clones for off-targets, but at the moment, it is not practical for systematic study of a large number of guide RNAs to determine the rules governing Cas9 specificity.

Whole genome binding

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) is a widely used technique for assaying genome-wide binding of proteins on DNA in vivo [53]. Briefly, live cells are crosslinked, lysed and chromatin fragmented and then immunoprecipitated to pull down DNA bound by a specific protein. The DNA is then purified and assayed by microarray or NGS. Compared to other readouts, such as indels that are downstream of the repair pathway, or gene expression changes, which are also affected by relative position of binding to the transcription start site, ChIP provides direct evidence for Cas9 binding on the genome. We and other groups recently generated the first maps of dCas9 binding on mammalian genomes [37,44,45]; all three studies revealed a large number of binding sites, for example up to six thousand in mouse embryonic stem cells, as well as substantial variation (200 fold) in the number of off-target sites between sgRNAs [37]. Specificity was not altered by fusion to an effector domain, as dCas9-KRAB had a similar binding profile to dCas9 alone [45]. Surprisingly, two of these studies observed little cutting/mutation at most off-targets tested, while one study observed significant cleavage at 30 out of 57 selected off-target sites, albeit at a substantially lower rate than on-target cleavage [44]. We further observed little to none of the off-target gene expression change which would presumably result from strong dCas9 binding at many off-target sites (Wu et al., unpublished data). It is possible that most of the off-targets detected by ChIP are weak and transient interactions stabilized by crosslinking. Native ChIP without crosslinking may help to clarify this question. The other limitation of ChIP approach is that it is inherently biased towards open chromatin and highly transcribed genes [54]. There could be other biases that remain to be discovered. For example, we failed to detect binding at previously validated off-target sites using an NAG PAM [37]. It is also unclear whether the two mutations introduced in dCas9 alter the target binding specificity as compared to wild type active Cas9.

Transcriptome profiling

For application in transcription modulation, transcriptome profiling by either microarray or RNA-seq is the ultimate read out for assessing off-target effects. In all published cases [25,27,55], no significant off-target gene expression changes were observed, which again is unexpected given the large number of off-target binding sites reported in ChIP-based studies, and that off-target binding is enriched in accessible active regulatory elements [37]. It also remains to be seen whether marginally affected genes are enriched for off-target binding sites.

Determinants of Cas9/sgRNA Specificity

Despite potential bias, the assays and studies described above revealed many factors that could affect Cas9/sgRNA targeting specificity (Figure 2), and these can be broadly classified into two categories. First, the intrinsic specificity encoded in the Cas9 protein, which likely determines the relative importance of each position in the sgRNA for target recognition, which may vary for different sgRNA sequences. Secondly, the specificity also depends on the relative abundance of effective Cas9/sgRNA complex with respect to effective target concentration. Below we discuss factors that could affect target specificity.

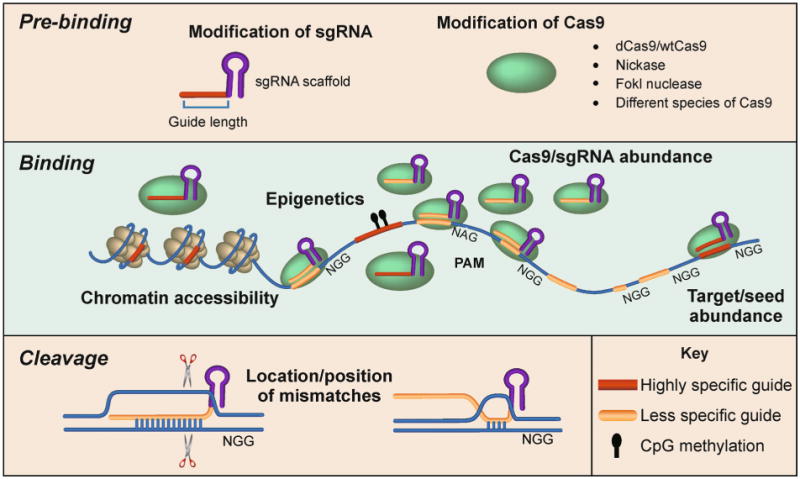

Figure 2. Factors that impact Cas9 specificity.

(Top) Before Cas9 is introduced to the system, specificity can be modified by altering the architecture of the single guide RNA (sgRNA) or the Cas9 protein itself. (Middle) At the DNA level, beyond the PAM requirement for binding, closed chromatin and methylated DNA negatively impact Cas9 binding, while increased abundance of Cas9/sgRNA complexes and guide sequences in the genome positively impact Cas9 binding. (Bottom) Although Cas9 can transiently bind DNA that is complementary to only a small seed sequence in the sgRNA, only sequences with extensive complementarity to the guide will be cleaved or direct activation or silencing of targeted genes.

PAM

The protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM) is strictly required to be immediately next to the 3′ end of the target sequence. The PAM is recognized by an individual domain in the Cas9 protein [56], and the PAM sequence varies across bacteria species [57,58]. Presumably species with longer PAM, having less targetable sites in the genome, will have correspondingly fewer off-targets, although this has not been directly tested. For the widely used Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes, the PAM is typically NGG, where the first position shows no nucleotide bias. Recent data suggested that PAM binding is required for both opening the DNA and target cleavage [56,59]. Both in vitro [38] and in vivo [29,34,60] cleavage data suggested that NAG is also tolerated to some extent, especially when Cas9/sgRNA is in excess to target DNA. In addition, other variants that contain at least one of the two G's at position 2 and 3, i.e. NNG or NGN, could lead to some cleavage activity in vitro under Cas9 excess conditions [38]. Interestingly recent genome-wide ChIP-seq data revealed no significant Cas9 binding at NAG targets [37,44,45], including previously validated off-target NAG cleavage sites, suggesting ChIP may not be able to detect off-target sites with certain PAMs.

Seed

In the original characterization of CRISPR-Cas9 [7], mismatches in the first 7 positions (PAM-distal) of the guide RNA are well tolerated in terms of cleavage of a plasmid in vitro. Further studies in bacteria and mammalian cells showed that mismatches in the 10-12 base pairs in the PAM-proximal region usually lead to decrease or even complete abolishment of target cleavage activity. Another study reported that Cas9 can even cleave DNA sequences that contain insertions or deletions relative to the guide RNA; however many of these sites could be alternatively aligned to contain only mismatches to the guide [61]. Thus, the PAM-proximal 10-12 bases have been defined as the seed region for Cas9 cutting activity [12,62]. However, a relatively comprehensive in vitro cleavage and selection approach revealed no clearly defined seed region for four guide RNAs, although the results confirmed that mismatches near the PAM region are less tolerated [38]. In contrast, in two genome-wide binding datasets, one out of two [45] and three of the four [37] sgRNAs tested showed a clearly defined seed region, only the first 5 nucleotides next to PAM. A third genome-wide binding dataset detected no obvious seed for twelve sgRNAs tested, although PAM proximal bases tended to be more preserved than PAM distal bases in binding sites [44]. However, the same data, when analyzed with our pipeline, revealed the 5-nucleotide seed region for three out of twelve sgRNAs (Wu et al., unpublished data); this is likely due to differences in selecting the best match to the guide region near binding sites, e.g. accepting matches with alternative PAMs. Hundreds of binding sites detected by ChIP in vivo contain only seed match with mismatches at all the other 15 positions in the guide RNA [37]. We also showed that seed-only sites could be bound by Cas9/sgRNA complex in vitro using a gel shift assay. The variation in the length of the seed detected by different assays likely stems from different concentrations of factors and lengths of dwell times required for Cas9 binding and cleavage.

Cas9/sgRNA abundance

Cas9 cutting becomes less specific at higher effective concentrations of Cas9/sgRNA complexes. For example, in vitro, when excessive amounts of Cas9/sgRNA complex are present, mismatches in the guide matching region are more tolerated, and Cas9 can even cut at sites with mismatches in the PAM region [38]. Hsu et al. also showed that in vivo the specificity (ratio of indel frequency at target vs off-target) increases when decreasing amounts of Cas9 and sgRNA plasmids are transfected into cells [34]. Genome-wide, we have found that increasing Cas9 protein levels by 2.6 fold leads to a 2.6 fold increase in the number of off-target binding peaks in the genome. On the other hand, at a constant level of Cas9 protein, titrating the amount of sgRNA expression plasmid transfected, and thus the abundance of sgRNA, largely determines the number of off-target binding sites in the mouse genome [37].

Target or guide sequence

In addition to targeting Cas9 to a certain region in the genome, the sequence of the sgRNA alone appears to affect specificity [13,34,35,38]. For example, the tolerance of mismatches at each position varies dramatically between different sgRNAs, an observation that remains to be understood.

Possible mechanisms whereby a change in sgRNA sequence could affect Cas9 specificity include: 1) Changes that alter the effective concentration of sgRNA (by modulating transcription of the sgRNA, the stability of the sgRNA, or sgRNA loading into Cas9). For example, we found that two mutations in the seed region can increase U6 promoter transcribed sgRNA's abundance by at least 7 fold [37]. 2) Changes that alter the number of seed-matching sites in the genome, which can vary by 100-fold. 3) Changes that depend on the local chromatin environment of the target DNA sequences (i.e. chromatin accessibility). 4) Changes that might cause off-target effects by blocking the binding of trans-acting factors that may potentially affect Cas9 binding or reporter gene transcription. 5) Changes that alter the thermodynamic stability of the guide RNA-DNA duplex. It is likely that the observed effects of sgRNA sequence on specificity are the result of multiple mechanisms described above. Below we will discuss some of these effects in detail.

Accessibility of seed match genomic sites

In cells DNA is packed in chromatin and may have limited accessibility for Cas9 PAM recognition and target binding. DNase I hypersensitivity (DHS) is typically considered to be an indicator of chromatin accessibility. We have shown that DHS is a strong predictor of whether a 5-nucleotide seed followed by NGG (seed + NGG) site will be bound in vivo [37], and others have also observed a strong correlation between Cas9-bound sites and open chromatin [44,45]. In fact, the number of seed + NGG sites in DHS peaks (accessible seed + NGG sites) accurately predicts the number of ChIP peaks detected in vivo (R2= 0.92) [37]. Interestingly, designed target sites not in DHS peaks show significant ChIP enrichment over background, in our case comparable to that of target sites in open chromatin, suggesting that chromatin accessibility is not a requirement for binding to the on-target site [37,44]. This is consistent with previous studies showing that dCas9-VP64 fusion protein could be targeted to non-open chromatin regions to activate target gene transcription [55]. In sum, chromatin accessibility seems to be preferentially facilitating off-target binding.

The preferential enrichment of off-targets in accessible chromatin has implications for dCas9-based transcriptome modulation. In fact, we found that regulatory elements of active genes, such as promoters and enhancers, are significantly enriched for off-target binding since those elements are accessible when active. To what extent these off-target binding events lead to gene expression change remains to be addressed.

Abundance of seed match genomic sites

Given that the binding seed length is relatively short (5 to 12), each guide RNA potentially has thousands to hundreds of thousands of seed match sites in the mammalian genome that are followed by NGG [37]. However, due to mutational bias and other sequence bias in the genome, the occurrence of specific seed sequences could vary dramatically. For example, there are about 1 million AAGGA + NGG sites in the mouse genome, compared to less than 10,000 CGTCG + NGG sites. Therefore it is important to consider abundance of seed sites when designing sgRNA targets for dCas9 based applications. We have shown that the number of accessible seed + NGG sites in the genome can very accurately predict the number of peaks detected by ChIP (R2= 0.92), although we only tested four guide RNAs [37].

Epigenetics

In addition to chromatin accessibility, we have also shown that for target sites with CpG dinucleotides, methylation status strongly correlates with ChIP signal [37]. Specifically, more methylation is associated with less binding, a correlation even stronger than DHS for the same set of sites. Consistent with the observation that CpG methylation is typically associated with chromatin silencing, we observed a strong negative correlation between DHS and CpG methylation. However, the correlation between CpG methylation and Cas9 binding remained strong even after subtracting the effect of DHS. Previously Hsu et al. showed that in vitro CpG methylation has no effects on Cas9 cutting of substrates with no mismatches to the guide RNA, and in vivo, Cas9 could mutate a promoter that is highly methylated, albeit with low indel frequency [34]. Taking this information together, we speculate that CpG methylation may represent chromatin accessibility not detected by DHS and like DHS, CpG methylation only affects binding at off-target sites. Similarly histone modifications may affect target site accessibility, although so far this has not been investigated.

Target sequence length

One might expect that if the guide region is longer than 20 nucleotides, a longer RNA-DNA duplex may be formed and thus the Cas9/sgRNA complex might have higher specificity. Ran et al. increased the length of the guide region to 30 nucleotides by extending the 5′ end of the sgRNA. Interestingly Northern blots detected that the extended 5′ end was trimmed in vivo [60], suggesting that Cas9 only protects about 20 nucleotides of the guide RNA and free sgRNA is largely unstable. On the other hand, it has been recently reported that when sgRNA is truncated to 17 or 18 nucleotides, the specificity increases dramatically [63]. The mechanism underlying this increased specificity is unclear. It was assumed the increased specificity is because the first 2-3 nucleotides are not necessary for on-target binding but instead stabilize off-target binding [63]. The other possibility is that shortened sgRNA may simply be less abundant or less efficiently loaded into Cas9.

sgRNA scaffold

In addition to the 5′ end, various modifications have been introduced to the scaffold region of the guide RNA, although their impact on target specificity is not well studied. Extension or truncation at the 3′ end can drastically change sgRNA expression levels [34], likely due to change in transcription or RNA stability, which in principle could affect specificity by tuning the effective concentration of Cas9/sgRNA complexes. Modifications have also been introduced to stabilize the sgRNA by flipping an A-U base pair at the beginning of the scaffold [31]. Increasing the length of a hairpin that is supposed to be bound by Cas9 also helps to increase the efficiencies for both imaging and transcription regulation, likely due to more efficient loading of sgRNA into Cas9. The effect of these modifications on the specificity of binding or cutting remains unclear, although it is reported that these modifications lead to higher signal to background ratio for imaging [31].

Strategies to Increase Specificity

Controlling Cas9/sgRNA abundance and duration

Typically Cas9 and sgRNA are expressed in cells by transient transfection of expressing plasmids. Titrating down the amount of plasmid DNA used in transfection increases specificity, although there is a trade-off for decreased efficiency at the on-target site. This is particularly an issue when the promoter is very strong, i.e. successfully transfected cells express a large amount of Cas9 and sgRNA leading to off-target effects. More recently, sgRNA has been expressed by RNA Pol II transcription and processed from introns, microRNAs, ribozymes, and RNA-triplex-helix structures, providing more flexible control of the sgRNA abundance [64,65].

Alternative delivery methods have also been developed to increase specificity. Compared to plasmid transfection based delivery, direct delivery of recombinant Cas9 protein and in vitro transcribed sgRNA, either individually or as purified complex, reduces off-targets in cells [66,67]. This is likely due to the rapid degradation of the protein and RNA in cells, which would lower the effective concentration of the Cas9-sgRNA effector complex and its duration in cells.

Paired nickase

The Cas9 “nickase” generated by mutating only one nuclease domain can only cleave one strand of the target DNA, which creates a nick thought to be repaired efficiently in cells. When the nickase is targeted to two neighboring regions on opposite strands, the offset double nicking leads to a double stranded break with tails that are degraded and subsequently indels in the target region. The requirement of dual Cas9 targeting to a nearby region dramatically increases the specificity, since it is generally unlikely that two guide RNAs will also have nearby off-targets. The limitation of this strategy is that nicks induced by Cas9 could still lead to mutations in off target sites via unknown mechanisms [13,29,60,63].

dCas9-FokI dimerization

FokI nuclease only cuts DNA when dimerized [68]. Fusion of dCas9 to FokI monomers creates an RNA-guided nuclease that only cuts the DNA when two guide RNAs bind nearby regions with defined spacing and orientation, thus substantially reducing off-target cleavage [69,70]. It has been reported that RNA-guided FokI nuclease is at least four fold more specific than paired Cas9 nickase [69], likely due to FokI nuclease only functioning when dimerized whereas Cas9 nickase can cleave as a monomer [70]. Similar to paired nickases, the requirement of two nearby PAM sites with defined spacing and orientation reduces the frequency of target sites in the genome.

Tools for Target Design and Off-target Prediction

Several tools have been developed for designing sgRNA targets, with the primary consideration to avoid off-targets in the genome [34,71–80]. These tools typically consider an input sequence, a genomic region, or a gene and output potential target/guide sequences with predicted minimized off-target effects. Many of the tools also provide predicted off-target sites for a given sgRNA. These tools vary in their scheme for scoring potential guides and off-targets. Some tools incorporate data from previous systematic mutagenic studies [34] or user-input penalties [72,77] to individually score off-targets based on location and number of mismatches to the guide. Other tools have binary criteria for off-targets, such as sites with less than a certain number of mismatches to the entire guide region [74,79,80], or to some defined PAM proximal or distal region [71,73,75,76,78]. Potential guides are generally ranked by a weighted sum of off-target scores, or by number of off-targets.

Several tools consider factors beyond position and number of mismatches. Some tools [77] include the option to score off-targets with alternate PAMs based on the finding that Cas9 cleaves these sites with lower efficiency [29,34,38,60]. In terms of the on-target site, various tools consider presence of SNPs and secondary structure [71] in the potential guide, which could impact targeting and loading of the sgRNA [81], genomic context of the guide (e.g. exons, transcripts, CpG islands), which could impact the intended purpose of the sgRNA [72,75], and GC content, which could impact effectiveness of the sgRNA [72,75,78,82].

Information from these tools is usually downloadable and sometimes viewable in an interactive format [34,75]. In addition, some tools provide support beyond finding potential guides, such as sequences of oligonucleotides for sgRNA construction [78–80] or primers for validation of cleavage at the target site [75,78]. Some tools also provide specialized modes for design of sgRNA with paired Cas9 nickases [34,72,73,78–80] or RNA-guided FokI nucleases [78–80].

Each of these tools has its advantages and disadvantages. Researchers seeking to design CRISPR-Cas9 targets in less well-studied organisms or alternative species of Cas9 will need to use tools that accept user-input genomes [71,73,74,77,78], are tailored for their organism [76], accept alternate PAM [73–75] or user-input PAM [77]. The desired purpose of the CRISPR-Cas9 guide is also an important factor to consider. For example, some tools focus on designing sgRNAs to target genes with high efficacy [75]. If off-target effects are more of a concern, it may be helpful to use a tool that scores predicted off-targets quantitatively [34,72,77]. The type of off-targets detected by each tool also varies; most tools only search for off-targets with few (typically three or less) PAM-proximal or total mismatches to the guide [71,75,76,79,80]. Considering what we have discussed in this review, especially for applications of dCas9, these may fail to detect many potential off-targets compared to tools that consider off-targets with more mismatches to the guide [34,72–74,77,78]. Since almost every tool has unique features, it may be useful to incorporate multiple tools during the design process. We refer readers to Supplementary Table for a more detailed comparison.

Overall, these tools could aid in designing sgRNA targets that have minimal sequence homology to other sites in the genome. However, many features that are important to sgRNA specificity, as we have discussed, remain to be implemented, such as impact of seed sequence on sgRNA abundance, seed abundance in the genome, and epigenetic features. These factors, as we have discussed, are currently thought to primarily affect binding, or dCas9 based applications.

Perspective

Despite intense study, the rules governing the specificity of Cas9/sgRNA targeting, especially target cutting and mutation remain elusive. At this stage, it is still challenging to predict genome-wide off-targets of Cas9 with any significant confidence. Although our genome-wide binding data set shows that the number of off-target peaks can be accurately predicted from the number of accessible seed + NGG sites, predicting binding at individual sites remains challenging [37]. This suggests that there could be other factors, such as higher-level chromatin structure, that further limit binding of Cas9.

In addition, the relationship between Cas9 binding and functional consequences such as cleavage, mutation and transcription perturbation remains elusive. Several lines of evidences suggest that most Cas9 off-target binding events may be transient and have little functional impact. First, in two separate studies, only one of the 295 off-target binding sites [37] or one out of 473 off-target binding sites [45] tested showed evidence of mutations in cells expressing active Cas9 and corresponding sgRNAs. Secondly, transcriptome profiling revealed negligible off-target gene expression change [25,27,55]. Furthermore, theoretical calculation implies an exponential decay in activity from Cas9 binding to downstream effects such as gene expression change [29]. However, a direct comparison between genome-wide binding, cutting, and transcriptome change will be needed to support this claim.

The current rules of Cas9/sgRNA specificity are likely incomplete and biased. Most assays described here are biased, and may only detect a fraction of the off-target sites in cells and predict many false positives. Integration of multiple assays will likely lead to more comprehensive and more accurate identification of off-targets. For example, intersecting ChIP-detected Cas9 binding sites with whole-genome sequencing data will likely lead to authentic Cas9 target sites while removing Cas9-independent false positives, such as sequencing error or ChIP bias.

In addition to biased assays, the rules learned from each study are also likely biased by the small number of sgRNAs studied, given that the target specificity highly depends on the target sequence. Most of the assays described here are difficult to scale-up, such as ChIP, in vitro selection, and whole-genome sequencing. Further development of multiplexable unbiased assays, such as DSB capture with barcoded linkers, could facilitate the study of large number of sgRNAs at the same time.

The issue of off-targets is most critical in use of the Cas9 system to mutate specific genes. Here off-targets could generate spurious phenotypes and mistaken interpretations. This is particularly a concern when a large library of Cas9 vectors is screened with selective conditions for specific phenotypes. In this case a rare off-target mutation could be selected and the phenotype accredited to the on-target gene. The only really valid assay under these conditions is the deep sequencing of the total genome of the cloned mutated cell. However, this is much too expensive for most experiments and will only be done in particular cases. The principles summarized here about specificity of the Cas9 system hopefully will lead to experimental designs that optimize the probability of obtaining desired on-target mutants in the absence of unknown off-target changes.

Lastly, alternative Cas9 protein and guide RNA architecture may improve specificity. Several alternative Cas9 proteins from various bacteria have been studied and display very different PAM sequences [83]. Comprehensive characterization of the specificity, such as genome-wide binding and cutting, may identify novel Cas9 proteins with dramatically improved specificity. With an available crystal structure [56], it is also possible to design a new Cas9 protein with increased specificity via protein engineering and in vitro evolution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Sharp lab members for discussion and critical reading of the manuscript, and M. Lindstrom for assistance on constructing figures. This work was supported by United States Public Health Service grants RO1-GM34277 and R01-CA133404 from the National Institutes of Health (P.A.S.), PO1-CA42063 from the National Cancer Institute (P.A.S.), and partially by Cancer Center Support (core) grant P30-CA14051 from the National Cancer Institute. X.W. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute International Student Research fellow.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests: The authors Xuebing Wu, Andrea J. Kriz and Phillip A. Sharp declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary materials can be found online with this article at DOI 10.1007/s40484-014-0030-x.

References

- 1.Marraffini LA, Sontheimer EJ. CRISPR interference: RNA-directed adaptive immunity in bacteria and archaea. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:181–190. doi: 10.1038/nrg2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrangou R, Marraffini LA. CRISPR-Cas systems: Prokaryotes upgrade to adaptive immunity. Mol Cell. 2014;54:234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deveau H, Garneau JE, Moineau S. CRISPR/Cas system and its role in phage-bacteria interactions. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010;64:475–493. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horvath P, Barrangou R. CRISPR/Cas, the immune system of bacteria and archaea. Science. 2010;327:167–170. doi: 10.1126/science.1179555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van der Oost J, Jore MM, Westra ER, Lundgren M, Brouns SJJ. CRISPR-based adaptive and heritable immunity in prokaryotes. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terns MP, Terns RM. CRISPR-based adaptive immune systems. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2011;14:321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mali P, Esvelt KM, Church GM. Cas9 as a versatile tool for engineering biology. Nat Methods. 2013;10:957–963. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sander JD, Joung JK. CRISPR-Cas systems for editing, regulating and targeting genomes. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:347–355. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang F, Wen Y, Guo X. CRISPR/Cas9 for genome editing: progress, implications and challenges. Hum Mol Genet. 2014 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu PD, Lander ES, Zhang F. Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell. 2014;157:1262–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Church GM. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang H, Wang H, Shivalila CS, Cheng AW, Shi L, Jaenisch R. One-step generation of mice carrying reporter and conditional alleles by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell. 2013;154:1370–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jao LE, Wente SR, Chen W. Efficient multiplex biallelic zebrafish genome editing using a CRISPR nuclease system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:13904–13909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308335110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canver MC, Bauer DE, Dass A, Yien YY, Chung J, Masuda T, Maeda T, Paw BH, Orkin SH. Characterization of genomic deletion efficiency mediated by CRISPR/Cas9 in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2014 doi: 10.1074/ibc.M114.564625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiao A, Wang Z, Hu Y, Wu Y, Luo Z, Yang Z, Zu Y, Li W, Huang P, Tong X, et al. Chromosomal deletions and inversions mediated by TALENs and CRISPR/Cas in zebrafish. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torres R, Martin MC, Garcia A, Cigudosa JC, Ramirez JC, Rodriguez-Perales S. Engineering human tumour-associated chromosomal translocations with the RNA-guided CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3964. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Auer TO, Duroure K, De Cian A, Concordet JP, Del Bene F. Highly efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knock-in in zebrafish by homology-independent DNA repair. Genome Res. 2014;24:142–153. doi: 10.1101/gr.161638.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hruscha A, Krawitz P, Rechenberg A, Heinrich V, Hecht J, Haass C, Schmid B. Efficient CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing with low off-target effects in zebrafish. Development. 2013;140:4982–4987. doi: 10.1242/dev.099085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwank G, Koo BK, Sasselli V, Dekkers JF, Heo I, Demircan T, Sasaki N, Boymans S, Cuppen E, van der Ent CK, et al. Functional repair of CFTR by CRISPR/Cas9 in intestinal stem cell organoids of cystic fibrosis patients. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:653–658. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu Y, Liang D, Wang Y, Bai M, Tang W, Bao S, Yan Z, Li D, Li J. Correction of a genetic disease in mouse via use of CRISPR-Cas9. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:659–662. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yin H, Xue W, Chen S, Bogorad RL, Benedetti E, Grompe M, Koteliansky V, Sharp PA, Jacks T, Anderson DG. Genome editing with Cas9 in adult mice corrects a disease mutation and phenotype. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:551–553. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larson MH, Gilbert LA, Wang X, Lim WA, Weissman JS, Qi LS. CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:2180–2196. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilbert LA, Larson MH, Morsut L, Liu Z, Brar GA, Torres SE, Stern-Ginossar N, Brandman O, Whitehead EH, Doudna JA, et al. CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell. 2013;154:442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qi LS, Larson MH, Gilbert LA, Doudna JA, Weissman JS, Arkin AP, Lim WA. Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-guided platform for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Cell. 2013;152:1173–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng AW, Wang H, Yang H, Shi L, Katz Y, Theunissen TW, Rangarajan S, Shivalila CS, Dadon DB, Jaenisch R. Multiplexed activation of endogenous genes by CRISPR-on, an RNA-guided transcriptional activator system. Cell Res. 2013;23:1163–1171. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kearns NA, Genga RMJ, Enuameh MS, Garber M, Wolfe SA, Maehr R. Cas9 effector-mediated regulation of transcription and differentiation in human pluripotent stem cells. Development. 2014;141:219–223. doi: 10.1242/dev.103341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mali P, Aach J, Stranges PB, Esvelt KM, Moosburner M, Kosuri S, Yang L, Church GM. CAS9 transcriptional activators for target specificity screening and paired nickases for cooperative genome engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:833–838. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farzadfard F, Perli SD, Lu TK. Tunable and multifunctional eukaryotic transcription factors based on CRISPR/Cas. ACS Synth Biol. 2013;2:604–613. doi: 10.1021/sb400081r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen B, Gilbert LA, Cimini BA, Schnitzbauer J, Zhang W, Li GW, Park J, Blackburn EH, Weissman JS, Qi LS, et al. Dynamic imaging of genomic loci in living human cells by an optimized CRISPR/Cas system. Cell. 2013;155:1479–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qiu P, Shandilya H, D'Alessio JM, O'Connor K, Durocher J, Gerard GF. Mutation detection using Surveyor nuclease. Biotechniques. 2004;36:702–707. doi: 10.2144/04364PF01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mashal RD, Koontz J, Sklar J. Detection of mutations by cleavage of DNA heteroduplexes with bacteriophage resolvases. Nat Genet. 1995;9:177–183. doi: 10.1038/ng0295-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsu PD, Scott DA, Weinstein JA, Ran FA, Konermann S, Agarwala V, Li Y, Fine EJ, Wu X, Shalem O, et al. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:827–832. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu Y, Foden JA, Khayter C, Maeder ML, Reyon D, Joung JK, Sander JD. High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:822–826. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carroll D. Staying on target with CRISPR-Cas. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:807–809. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu X, Scott DA, Kriz AJ, Chiu AC, Hsu PD, Dadon DB, Cheng AW, Trevino AE, Konermann S, Chen S, et al. Genome-wide binding of the CRISPR endonuclease Cas9 in mammalian cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:670–676. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pattanayak V, Lin S, Guilinger JP, Ma E, Doudna JA, Liu DR. High-throughput profiling of off-target DNA cleavage reveals RNA-programmed Cas9 nuclease specificity. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:839–843. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guilinger JP, Pattanayak V, Reyon D, Tsai SQ, Sander JD, Joung JK, Liu DR. Broad specificity profiling of TALENs results in engineered nucleases with improved DNA-cleavage specificity. Nat Methods. 2014;11:429–435. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pattanayak V, Ramirez CL, Joung JK, Liu DR. Revealing off-target cleavage specificities of zinc-finger nucleases by in vitro selection. Nat Methods. 2011;8:765–770. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gabriel R, Lombardo A, Arens A, Miller JC, Genovese P, Kaeppel C, Nowrouzi A, Bartholomae CC, Wang J, Friedman G, et al. An unbiased genome-wide analysis of zinc-finger nuclease specificity. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:816–823. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sander JD, Ramirez CL, Linder SJ, Pattanayak V, Shoresh N, Ku M, Foden JA, Reyon D, Bernstein BE, Liu DR, et al. In silico abstraction of zinc finger nuclease cleavage profiles reveals an expanded landscape of off-target sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e181. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cho SW, Kim S, Kim Y, Kweon J, Kim HS, Bae S, Kim JS. Analysis of off-target effects of CRISPR/Cas-derived RNA-guided endonucleases and nickases. Genome Res. 2014;24:132–141. doi: 10.1101/gr.162339.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuscu C, Arslan S, Singh R, Thorpe J, Adli M. Genome-wide analysis reveals characteristics of off-target sites bound by the Cas9 endonuclease. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:677–683. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O'Geen H, Henry IM, Bhakta MS, Meckler JF, Segal DJ. A genome-wide analysis of Cas9 binding specificity using ChIP-seq and targeted sequence capture. BioRxiv, Cold Spring Harbor Labs; 2014. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/005413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chailleux C, Aymard F, Caron P, Daburon V, Courilleau C, Canitrot Y, Legube G, Trouche D. Quantifying DNA double-strand breaks induced by site-specific endonucleases in living cells by ligation-mediated purification. Nat Protoc. 2014;9:517–528. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crosetto N, Mitra A, Silva MJ, Bienko M, Dojer N, Wang Q, Karaca E, Chiarle R, Skrzypczak M, Ginalski K, et al. Nucleotide-resolution DNA double-strand break mapping by next-generation sequencing. Nat Methods. 2013;10:361–365. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chiu H, Schwartz HT, Antoshechkin I, Sternberg PW. Transgene-free genome editing in Caenorhabditis elegans using CRISPR-Cas. Genetics. 2013;195:1167–1171. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.155879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feng Z, Mao Y, Xu N, Zhang B, Wei P, Yang DL, Wang Z, Zhang Z, Zheng R, Yang L, et al. Multigeneration analysis reveals the inheritance, specificity, and patterns of CRISPR/Cas-induced gene modifications in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:4632–4637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400822111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang H, Zhang J, Wei P, Zhang B, Gou F, Feng Z, Mao Y, Yang L, Zhang H, Xu N, et al. The CRISPR/Cas9 system produces specific and homozygous targeted gene editing in rice in one generation. Plant Biotechnol J. 2014 doi: 10.1111/pbi.12200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Veres A, Gosis BS, Ding Q, Collins R, Ragavendran A, Brand H, Erdin S, Talkowski ME, Musunuru K. Low incidence of off-target mutations in individual CRISPR-Cas9 and TALEN targeted human stem cell clones detected by whole-genome sequencing. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith C, Gore A, Yan W, Abalde-Atristain L, Li Z, He C, Wang Y, Brodsky RA, Zhang K, Cheng L, et al. Whole-genome sequencing analysis reveals high specificity of CRISPR/Cas9 and TALEN-based genome editing in human iPSCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:12–13. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park PJ. ChIP-seq: advantages and challenges of a maturing technology. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:669–680. doi: 10.1038/nrg2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Teytelman L, Thurtle DM, Rine J, van Oudenaarden A. Highly expressed loci are vulnerable to misleading ChIP localization of multiple unrelated proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:18602–18607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316064110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perez-Pinera P, Kocak DD, Vockley CM, Adler AF, Kabadi AM, Polstein LR, Thakore PI, Glass KA, Ousterout DG, Leong KW, et al. RNA-guided gene activation by CRISPR-Cas9-based transcription factors. Nat Methods. 2013;10:973–976. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nishimasu H, Ran FAA, Hsu PDD, Konermann S, Shehata SII, Dohmae N, Ishitani R, Zhang F, Nureki O. Crystal structure of Cas9 in complex with guide RNA and target DNA. Cell. 2014;156:935–949. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garneau JE, Dupuis M, Villion M, Romero DA, Barrangou R, Boyaval P, Fremaux C, Horvath P, Magadán AH, Moineau S. The CRISPR/Cas bacterial immune system cleaves bacteriophage and plasmid DNA. Nature. 2010;468:67–71. doi: 10.1038/nature09523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Y, Heidrich N, Ampattu BJ, Gunderson CW, Seifert HS, Schoen C, Vogel J, Sontheimer EJ. Processing-independent CRISPR RNAs limit natural transformation in Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Cell. 2013;50:488–503. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sternberg SH, Redding S, Jinek M, Greene EC, Doudna JA. DNA interrogation by the CRISPR RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9. Nature. 2014;507:62–67. doi: 10.1038/nature13011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ran FA, Hsu PD, Lin CY, Gootenberg JS, Konermann S, Trevino AE, Scott DA, Inoue A, Matoba S, Zhang Y, et al. Double nicking by RNA-guided CRISPR Cas9 for enhanced genome editing specificity. Cell. 2013;154:1380–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lin Y, Cradick TJ, Brown MT, Deshmukh H, Ranjan P, Sarode N, Wile BM, Vertino PM, Stewart FJ, Bao G. CRISPR/Cas9 systems have off-target activity with insertions or deletions between target DNA and guide RNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:7473–7485. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jiang W, Bikard D, Cox D, Zhang F, Marraffini LA. RNA-guided editing of bacterial genomes using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:233–239. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fu Y, Sander JD, Reyon D, Cascio VM, Joung JK. Improving CRISPR-Cas nuclease specificity using truncated guide RNAs. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:279–284. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nissim L, Perli SD, Fridkin A, Perez-Pinera P, Lu TK. Multiplexed and programmable regulation of gene networks with an integrated RNA and CRISPR/Cas toolkit in human cells. Mol Cell. 2014;54:698–710. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kiani S, Beal J, Ebrahimkhani MR, Huh J, Hall RN, Xie Z, Li Y, Weiss R. CRISPR transcriptional repression devices and layered circuits in mammalian cells. Nat Methods. 2014;11:723–726. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim S, Kim D, Cho SW, Kim J, Kim JS. Highly efficient RNA-guided genome editing in human cells via delivery of purified Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Genome Res. 2014;24:1012–1019. doi: 10.1101/gr.171322.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ramakrishna S, Kwaku Dad AB, Beloor J, Gopalappa R, Lee SK, Kim H. Gene disruption by cell-penetrating peptide-mediated delivery of Cas9 protein and guide RNA. Genome Res. 2014;24:1020–1027. doi: 10.1101/gr.171264.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bitinaite J, Wah DA, Aggarwal AK, Schildkraut I. FokI dimerization is required for DNA cleavage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10570–10575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guilinger JP, Thompson DB, Liu DR. Fusion of catalytically inactive Cas9 to FokI nuclease improves the specificity of genome modification. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:577–582. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tsai SQ, Wyvekens N, Khayter C, Foden JA, Thapar V, Reyon D, Goodwin MJ, Aryee MJ, Joung JK. Dimeric CRISPR RNA-guided FokI nucleases for highly specific genome editing. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:569–576. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ma M, Ye AY, Zheng W, Kong L. A guide RNA sequence design platform for the CRISPR/Cas9 system for model organism genomes. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:270805. doi: 10.1155/2013/270805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Heigwer F, Kerr G, Boutros M. E-CRISP: fast CRISPR target site identification. Nat Methods. 2014;11:122–123. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xiao A, Cheng Z, Kong L, Zhu Z, Lin S, Gao G. CasOT: a genome-wide Cas9/gRNA off-target searching tool. Bioinformatics. 2014 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bae S, Park J, Kim JS. Cas-OFFinder: a fast and versatile algorithm that searches for potential off-target sites of Cas9 RNA-guided endonucleases. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1473–1475. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Montague TG, Cruz JM, Gagnon JA, Church GM, Valen E. CHOPCHOP: a CRISPR/Cas9 and TALEN web tool for genome editing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W401–407. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gratz SJ, Ukken FP, Rubinstein CD, Thiede G, Donohue LK, Cummings AM, O'Connor-Giles KM. Highly specific and efficient CRISPR/Cas9-catalyzed homology-directed repair in Drosophila. Genetics. 2014;196:961–971. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.160713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Aach J, Mali P, Church GM. CasFinder: Flexible algorithm for identifying specific Cas9 targets in genomes. BioRxiv, Cold Spring Harbor Labs; 2014. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/005074. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xie S, Shen B, Zhang C, Huang X, Zhang Y. sgRNAcas9: A software package for designing CRISPR sgRNA and evaluating potential off-target cleavage sites. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e100448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sander JD, Zaback P, Joung JK, Voytas DF, Dobbs D. Zinc Finger Targeter (ZiFiT): an engineered zinc finger/target site design tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W599–605. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sander JD, Maeder ML, Reyon D, Voytas DF, Joung JK, Dobbs D. ZiFiT (Zinc Finger Targeter): an updated zinc finger engineering tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W462–468. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Makarova KS, Haft DH, Barrangou R, Brouns SJJ, Charpentier E, Horvath P, Moineau S, Mojica FJM, Wolf YI, Yakunin AF, et al. Evolution and classification of the CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:467–477. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang T, Wei JJ, Sabatini DM, Lander ES. Genetic screens in human cells using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Science. 2014;343:80–84. doi: 10.1126/science.1246981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Esvelt KM, Mali P, Braff JL, Moosburner M, Yaung SJ, Church GM. Orthogonal Cas9 proteins for RNA-guided gene regulation and editing. Nat Methods. 2013;10:1116–1121. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.