Abstract

A partnership was formed between the University of Hawai‘i at Hilo Daniel K. Inouye College of Pharmacy (DKICP) and the Department of Health to carry out the Hawai‘i Asthma Friendly Pharmacy Project (HAFPP), which utilizes pharmacy students as a workforce to administer Asthma Control Tests™ (ACT), and provide Asthma Action Plans (AAP) and inhaler technique education. Evaluation of data from a pilot project in 2008 with first and second year students prompted more intensive training in therapeutics, inhaler medication training, and communication techniques. Data collection began when two classes of students were first and second year students and continued until the students became fourth year students in their advanced experiential ambulatory care clinic and retail community pharmacy rotations. Patients seen included pediatric (32%) and adult (68%) aged individuals. Hawai‘i County was the most common geographic site (50%) and most sites were retail pharmacies (72%). Administered ACT surveys (N=96) yielded a mean score of 19.64 (SD +/−3.89). In addition, 12% of patients had received previous ACT, and 47% had previous AAPs. Approximately 83% of patients received an additional intervention of AAP and inhaler education with 73% of these patients able to demonstrate back proper inhaler technique. Project challenges included timing of student training, revising curriculum and logistics of scheduling students to ensure consistent access to patients.

Introduction

The National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) established new patient specific guidelines in 1991 with revisions in 2002 to emphasize the use of long-term asthma inhaler controller medications to reduce morbidity and mortality for chronic asthma sufferers.1 Physicians have reported barriers to utilizing these practice guidelines including lack of awareness, familiarity, and training with the Asthma Control Test (ACT), and difficulty overcoming previous practice habits.2–4

Data from the 2008 Behavioral Risk Factor System (BRFSS) reported that the prevalence of asthma for both adults and children was higher in Hawai‘i County (12.2% and 17.0%, respectively) as compared to 9.6% among adults and 12.7% among children statewide. Table 1 compares the prevalence and presents the breakdown within Hawai‘i County. Survey results in 2012 produced similar results.5 A study by Berry, et al,6 described the concept of the Asthma Friendly Pharmacies (AFP) model that provided focused asthma education to community pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, and pharmacy students on various asthma-related interventions including resolving medication-related adverse effects, patient education on inhaler technique, and improving the pharmacist/patient and pharmacist/primary care provider relationship. Providers gave over 2000 patient interventions that included patient education on topics such as the difference between asthma controllers and quick relief medications, medication regimens, device technique, and side effects.6 Other studies have also demonstrated effective pharmacist management as health extenders for chronic care asthma.7–9 While access to asthma specialists may be limited, asthma patients in Hawai‘i have access to community retail pharmacists when they pick up their asthma inhaler prescriptions. Hence, training student pharmacists in Hawai‘i on the use of the ACT and involving them in a public health project seemed appropriate.

Table 1.

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

| Asthma Prevalence in Adults | 2008 | 2012 |

| Statewide | 9.6% | 8.9% |

| Hawai‘i County | 12.2% | 9.7% |

| Hilo | 16.7% | 9.5% |

| North Hawai‘i | 12.9% | 8.5% |

| Puna/Ka‘u | 8.0% | 10.9% |

| Kona | 10.3% | 9.3% |

| Asthma Prevalence in Children | 2008 | 2012 |

| Statewide | 12.7% | 12.2% |

| Hawai‘i County | 17.0% | 10.4% |

| Hilo | 18.6% | 13.7%* |

| North Hawai‘i | 12.8% | 7.2%* |

| Puna/Ka‘u | 16.2% | 10.5%* |

| Kona | 7.3% | 9.0%* |

Data combined from 2011–2012

A collaborative partnership was formed between the Daniel K. Inouye College of Pharmacy (DKICP) and the Hawai‘i Department of Health (DOH) to carry out the Hawai‘i Asthma Friendly Pharmacy Project (HAFPP) modeled after a study performed by Berry, et al. The objective of this four-year study was to explore the feasibility of utilizing pharmacy students as a workforce entity to aid in a public health project. This paper describes the results of this effort.

Methods

The project protocol and patient consent forms received approval from both the DOH Institutional Review Board and the University of Hawai‘i Committee on Human Studies (CHS). Initial planning meetings were held with the DOH HAFPP project staff, the DKICP Director of Experiential Education and several community pharmacy leaders. This initial group formulated the list of targeted medications in Figure 1. As the project progressed, quarterly meetings were held to discuss project objectives, progress in pharmacist and student training, and project implementation. Prior to the start of the project in 2008, HAFPP funded a pulmonologist-led continuing education and implementation session for the community retail pharmacist preceptors and DKICP faculty in East Hawai‘i. HAFPP funded the printing of hard copy ACT forms, Asthma Action Plans and other patient education materials (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Asthma Medications Included in Asthma Friendly Pharmacy Project

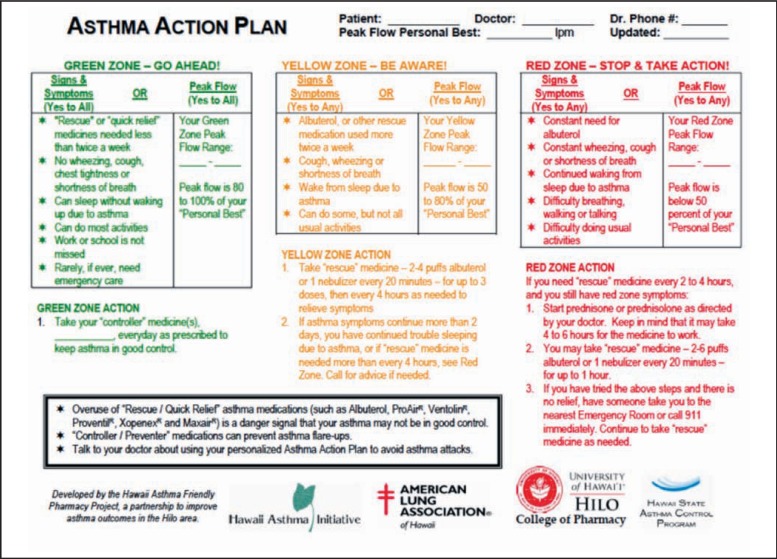

Figure 2.

Asthma Action Plan

Two phases of the project included a pilot study held in 2008–2009, and a second phase of the study occurring from May 2010–May 2012. The same students were studied in both phases of the study. The pilot study utilized 170 PY1 and PY2 students to administer the ACT test to patients in the community pharmacy retail sites and ambulatory care clinics. Due to the beginning level of training of these students, community pharmacist preceptors and DKICP practice faculty performed patient follow up for AAP and inhaler education if the patient was found to have uncontrolled asthma (ACT ≤19). Analysis of the pilot study data revealed four major areas of concern: (1) the limited ability of the students to confidently perform the ACT early on in their training due to gaps in understanding of the disease, knowledge of the medications, and adequate communication and patient education skills; (2) insufficient data collection tools; (3) inadequate preparation of the pharmacist preceptor; and (4) inconsistent hours at practice sites, which limited student access to the patients.

Based on the 2008 pilot project data, the project group made suggestions to the DKICP on how to change the didactic curriculum specific to asthma therapeutics, patient interview, and counseling skills. Additional workshop time was added to supplement the asthma therapeutics learning module to develop students' communication and interview skills on inhaler technique and education. Changes were also made to the third year capstone course, Applied Pharmaceutical Care Didactic, implemented Objective, Subjective, Comprehensive Exams (OSCE) to demonstrate proficiency on inhaler technique and patient education. Pharmacy preceptors were trained again on the study protocol, given the data from the 2008 pilot, as well as presented information on the challenges observed in the 2008 pilot.

Prior to the second phase of the study, better technology for data collection was implemented with a software program called E*Value which allowed for on-line data collection. Changes made to curriculum and rotation scheduling is detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Didactic and Experiential Curriculum Changes

| Area | 2008 | By 2012 |

| Curriculum | Brief orientation to interview skills and ACT (PY1) | Orientation and reinforcement of interview skills and ACT (PY1) |

| Asthma therapeutics module (PY2) | Asthma therapeutics module + hands on inhaler workshop onvarious types of inhalers (PY2) | |

| Simulation mannequin in asthma patient case (PY2) | ||

| Applied Pharmaceutical Care Course (PY3) Objective/Subjective Clinical Exams (OSCE) for inhaler education (PY3) | ||

| Technology | Paper ACT, manual collection, DOH link | E-value software to include ACT scores and interventions |

| Experiential Rotation Scheduling | PY1 rotation: 4 hrs/week × 15 weeks | PY1 rotation: daily × 4 consecutive weeks PY4 rotation: daily × 6 consecutive weeks |

| Preceptor training | 1 hour CE on Asthma guidelines and Asthma Friendly Project | Annual preceptor training on ACT, AAP and student involvement |

The second phase of the study occurred from May 2010 – May 2012 when the same 170 students who had now advanced into their PY4 year were then dispersed to pharmacies on the islands of Maui (retail, ambulatory care), Kaua‘i (retail), O‘ahu (retail, ambulatory care), and Hawai‘i (retail, ambulatory care, hospital). Students were asked to administer ACTs, provide an AAP and inhaler education and document their interventions. Students obtained consent from the patient or patient's guardian before administering the ACT. In the retail pharmacy rotations, possible patients were identified when they picked up targeted medications. In ambulatory care clinics, students performed the three steps as part of their regular medication intake interview at the start of a patient's clinic appointment. Students asked two additional survey questions pertaining to whether the patient had ever had an ACT performed or had ever been counseled with an AAP. Consistent with the scoring methodology for ACTs, the final scores were calculated by adding up the individual item scores of the five-item survey. The two additional questions were answered as “yes” or “no.”

Students were asked to document their interventions into E*Value specifically documenting types of intervention such as AAPs and inhaler education, gender, site, ethnicity, and amount of time spent with the patient. HAFPP provided statistical analysis using SPSS 18.0, Chicago, IL.

Results

Table 3 describes the documented intervention data for the 96 ACT surveyed patients of whom 56% scored ≥19 (Mean ACT scores 19.64 (SD +/−3.89)), indicating adequate control of asthma symptoms. Of these patients, 12% had previous ACTs performed and 47% were given AAPs previously. Of the 96 patients given ACTs, 83 % were given additional interventions of an AAP and inhaler education. Of those given inhaler education, 73% were able to demonstrate back proper technique. Table 4 describes the demographics, geographic, and types of practice sites of patients who had documented interventions of AAP and/or inhaler education by student and patient demonstration (N=80, 83%). The majority of patients were seen in retail practice sites. Geographically, most patients were seen on Hawai‘i Island. Of the 170 students who were trained or eligible to participate in the study only 17% documented interventions.

Table 3.

ACT, AAP and Education Intervention for 2012

| Number of patients given ACT | 96 |

| % of patients given additional intervention (AAP and inhaler education) | 83 |

| % of patients able to demonstrate back proper inhaler technique after education | 73 |

| Avg. time spent/patient (min) | 18 |

Table 4.

Demographics of Patients who received AAP and/or Inhaler Education 2012

| N=80 patients | |

| % Pediatric | 32 |

| % Adult | 68 |

| % Male/Female | 52/48 |

| Ethnicities (%) | |

| African American | 4 |

| Asian | 12 |

| Caucasian | 18 |

| Filipino | 6 |

| Hispanic | 2 |

| Native Hawaiian | 22 |

| Mixed race | 6 |

| Other | 16 |

| Not noted | 14 |

| Geographic Sites (%) | |

| O‘ahu | 42 |

| Hawai‘i Island | 50 |

| Kaua‘i | 2 |

| Maui Island | 2 |

| Continental US | 4 |

| Type of Practice Site (%) | |

| Retail | 79 |

| Ambulatory Care Clinic | 21 |

Discussion

Asthma control requires vigilant monitoring of factors such as symptoms, dynamic pulmonary function, and patients' ability to function in their daily activities of life. Assessing one or several of these functions at any one point of care gives only a glimpse of a disease that requires chronic control with multiple assessment points over time. Tools such as the ACT were developed in 2004 by Nathan, et al,3 as a five-point patient-administered survey to assist practitioners in assessing asthma control in settings where spirometry or other testing may not be available.3 The ACT assesses, on a scale from 1–5, patients' scores for wheezing, coughing, chest tightness, and pain, as well as the frequency of use of short acting rescue inhalers. Also included is amount of time asthma has kept the patient from normal activities in work, school, or home; higher scores are indicative of better functioning. Scores of 19 or less indicate that asthma may not be well controlled.3 Schatz, et al,4 replicated the findings from Nathan in a population underserved by asthma specialists and concluded that the ACT is reliable, valid, and responsive to changes over time in asthma patients not under the care of an asthma specialist, and should help practitioners to improve assessment of asthma control in busy clinical settings.4 For patients with ACT score of 19 or higher, the study yielded a sensitivity and specificity of 71% for detecting patients with uncontrolled asthma. Hawai‘i's asthma patient population is similar to the Schatz, et al, study population in terms of the lack of asthma specialists on neighbor islands and limited access to specialists on O‘ahu. As a result, this study critically informed our study.

Other community-based asthma interventions by pharmacists have also been shown to be successful. In 1997, Rupp, et al, described an independent community pharmacy and local health maintenance organization (HMO) partnership that developed a Disease Specific Management (DSM) Program called Asthma Integrated Management (AIM).7 AIM targeted problematic pediatric patients aged 18 years or younger, and newly diagnosed or poorly controlled patients. Poorly controlled patients were defined as patients previously diagnosed with asthma experiencing one or more recent exacerbations. Problematic pediatric patients were defined as those who had learning impairments or disabilities; and those with a highly unstable social environment due to lack of a routine and reliable adult caregiver. The program was meant to supplement physician care. The clinical objectives were: (1) recognize and treat acute exacerbations; (2) minimize acute and chronic asthma symptoms; (3) maintain normal activities including exercise; (4) enhance patient education about asthma and its causes; (5) prevent side effects of treatment; (6) minimize the social and financial costs of asthma; and (7) achieve improvement in activities, symptoms, and emotional impact. The program required significant blocks of dedicated pharmacist interaction with the patient and the primary caregiver. Over a two-year period of time, 11 HMO patients were able to complete all the steps of the AIM program. Results showed significant improvement in quality of life and decrease in use of care services with a 77% reduction in hospitalizations, as well as lower emergency room and urgent care visits, by 78% and 25%, respectively. Although the numbers were small, the paper described an important component of a successful DSM program (an arrangement by which HMO patients had exclusive contracts with area chain pharmacies for their medications). When patients were allowed to fill prescriptions at non-HMO pharmacies (for convenience or other reasons), pharmacists were limited in their ability to carry out standardized type reviews such a drug use review, counseling and compliance; in addition, patients were more often lost to follow-up. With routine pick up of prescriptions, DSM appointments could be concurrently scheduled. A key to success in this program was consistent quality of pharmacist care achieved by implementing a standard AIM pharmacist training program.7

In Hawai‘i, Chan, et al, reported results specific to asthma education.9 The Military Community Asthma Program (MCAP) was developed in 1996 at the Tripler Army Medical Center on O‘ahu to address the high rate of hospitalizations for their pediatric asthma patients. The program developed inpatient and outpatient education processes where critical pathways required utilizing pharmacists who were trained in asthma education. A pre-study in 1997 showed a hospitalization rate of 3.2 per 1,000 children. The study enrolled 107 patients from late 1997 through January 1999. After implementation of MCAP, hospitalization rates decreased to 2.1 per 1,000 children in 1998 and to 1.9 per 1,000 children in 1999. The study also reported a trend toward decreased pediatric admission to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit for severe asthma, from 2.3–6.0 per 10,000 in 1994 to 1.7 per 10,000 in 1999. The study reported that the most critical element for successful asthma therapy was the delivery of the correct medication along with pharmacist education on correct multi-dose inhaler (MDI) therapy.9

In our study, the data collected from 2010–2012 indicated that students, if trained properly and in a stepwise fashion, are able to administer an ACT, create an AAP and provide counseling. However, due to the small size of the study, the impact on asthma control based upon interventions cannot be reliably discerned, although it is noteworthy that more than half of our patients (56%) had controlled asthma and that a majority of patients (73%) who were given education were able to demonstrate back proper technique.

A significant shortcoming of our study was the low percentage of documented participation by students. Although students were directed to take the initiative and report their scores and interventions, this project relied solely on voluntary student documentation. Students may have performed interventions and neglected to input the information. Other issues may have also affected the numbers of responses such as other disease management priorities during a patient's visit, patients not agreeing to participate, students forgetting to perform the task during the rotation, or students not being present when the patient came to pick up their prescriptions. Figures are not available to describe the total number of possible patient-student interactions based upon the number of eligible prescriptions from the list of earmarked inhalers. This would require all sites to report their total number of inhaler prescriptions over the study trial period of two years. In addition, many chronic medications such as asthma inhalers are refilled by mail order pharmacies as mandated by certain insurance companies, negating the need for a physical visit to the pharmacy. Future project design might target specific rotation sites to provide total number of possible patients, first time prescriptions, number of patients who refuse participation, and the number of patients seen by students as well as the type of interventions.

Conclusions

This small study explores the possibilities of utilizing pharmacy students in a public health project. Lessons learned were that students need consistent training in a disease state, medications, communication, and patient interactive skills in a building block model starting with their first year and with content and skills development continuing to build each year into their final fourth year. The changes developed for this study have been maintained in the curriculum and students know that ACTs are part of the assessment toolkit for managing asthma and are knowledgeable about the follow-up steps of giving AAP's and inhaler education. Project challenges included scheduling of students in rotation sites to provide consistent access to patients.

Although the majority of patients were seen in the retail pharmacy setting, time constraints and attendance to other duties limit the community retail pharmacist's availability to mentor early PY1 level students. The skill of administering ACTs could be taught in the first year, as students begin to develop patient interview and communication skills. This would allow them to continue to develop their communication skills during the second professional year while also being introduced to information on the disease and medication therapeutics. The third year would then solidify the didactic training and in the fourth year, the student would continue to practice these skills in the experiential setting. The limited patient data suggests that if given appropriate education, patients are able to demonstrate back proper inhaler technique.

Ideally, engaging students in a public health effort early in their professional education will instill the value for this type of service as a part of their professional career. Pharmacists are trained to provide service but not necessarily to think in terms of public health initiatives. This type of project helps to promote the professional contributions of pharmacists to public health.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors identify a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.National Institutes of Health, author. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Bethesda, MD: National Asthma Education and Prevention Program; 2002. Expert Panel Report 2 (updated) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfenden L, Diette G, Krishnan J, Skinner E, et al. Lowe physicians estimate of underlying asthma severity leads to under treatment. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:231–236. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, Schatz M, et al. Development of the Asthma Control Test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schatz M, Sorkness CA, Li JT, Marcus P, Murray JJ, Nathan RA, Kosinski M, Pendergraft TB, Jhingran PJ. “Asthma Control Test: reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients not previously followed by asthma specialists”. Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006 Mar;117(3):549–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krupitsky D, Reyes-Salvail F, Baker, Kromer K, Pobustrky A. State of Asthma Hawaii 2009, 2012. Honolulu, HI: Hawaii State Department of Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berry, Tricia M, Prosser, Theresa R, Wilson, Kristin, Castro Mario. “Asthma Friendly Pharmacies: A Model to Improve Communication and Collaboration among Pharmacists, Patients and Healthcare Providers”. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2011;88(Suppl 1) doi: 10.1007/s1152-010-9514-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moonie SA, Strunk RC, Crocker S, Curtis V, et al. “Community Asthma Program Improves Appropriate Prescribing in Moderate to Severe Asthma”. Journal of Asthma. 2005;42:281–289. doi: 10.1081/jas-200057900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rupp MT, McCallian DJ, Sheth KK. “Developing and Marketing a Community Pharmacy—Based Asthma Management Program. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1997;NS37:694–699. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)30269-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan DS, Callahan CW, Moreno C. “Multidisciplinary Education and Management for Children With Asthma. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001;58(15) doi: 10.1093/ajhp/58.15.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]