Abstract

Purpose.

Glaucoma is a major cause of vision loss due to retinal ganglion cell (RGC) degeneration. Therapeutic intervention controls increased IOP, but neuroprotection is unavailable. NogoReceptor1 (NgR1) limits adult central nervous system (CNS) axonal sprouting and regeneration. We examined NgR1 blocking decoy as a potential therapy by defining the pharmacokinetics of intravitreal NgR(310)-Fc, its promotion of RGC axonal regeneration following nerve crush, and its neuroprotective effect in a microbead glaucoma model.

Methods.

Human NgR1(310)-Fc was administered intravitreally, and levels were monitored in rat vitreal humor and retina. Axonal regeneration after optic nerve crush was assessed by cholera toxin β anterograde labeling. In a microbead model of glaucoma with increased IOP, the number of surviving and actively transporting RGCs was determined after 4 weeks by retrograde tracing with Fluro-Gold (FG) from the superior colliculus.

Results.

After intravitreal bolus administration, the terminal half-life of NgR1(310)-Fc between 1 and 7 days was approximately 24 hours. Injection of 5 μg protein once per week after optic nerve crush injury significantly increased RGCs with regenerating axons. Microbeads delivered to the anterior chamber increased pressure, and caused 15% reduction in FG-labeled RGCs of control rats, with a 40% reduction in large diameter RGCs. Intravitreal treatment with NgR1(310)-Fc did not reduce IOP, but maintained large diameter RGC density at control levels.

Conclusions.

Human NgR1(310)-Fc has favorable pharmacokinetics in the vitreal space and rescues large diameter RGC counts from increased IOP. Thus, the NgR1 blocking decoy protein may have efficacy as a disease-modifying therapy for glaucoma.

Keywords: glaucoma, regeneration, optic neuropathy

Blocking NgR1 function with a soluble decoy protein can be accomplished by intravitreal injection. The decoy injection permits axonal regeneration after crush injury and retinal ganglion cell survival after elevation of IOP.

Introduction

Glaucoma refers to a group of neurodegenerative eye disorders that can cause vision loss and blindness. The disease is characterized by loss of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) and axonal degeneration. Glaucoma often is, but not necessarily, associated with increased IOP. It has been estimated from population-based surveys that one in 40 adults over the age of 40 suffers from glaucoma with vision function loss1 and glaucoma is the second leading cause of blindness worldwide.2 Medical and surgical therapeutic intervention helps control one of the major risk factors (i.e., elevated IOP), but neuroprotective treatment does not exist today. There also is a critical and completely unmet medical need for therapies that deliver a degree of neurorestoration as the majority of glaucoma patients already have suffered significant loss of RGCs before diagnosis.3

The trajectories of axons and dendrites, and the sites of synapses, within the adult central nervous system (CNS) are relatively static.4,5 Proteins expressed by CNS oligodendrocytes, including Nogo-A (Rtn4A),6,7 myelin associated glycoprotein (MAG),8,9 and oligodendrocyte myelin glycoprotein (OMgp),10 are known to inhibit the extension of neuronal processes and the rearrangement of synaptic connectivity. The Nogo-66 Receptor 1 (NgR1) protein (Rtn4R) functions as a receptor for all three of these outgrowth inhibitors,11,12 as does PirB (LLRB3).13–15 Deletion of NgR1 reduces sensitivity to myelin inhibitors,16 and allows recovery in mice from stroke and spinal cord injuries.17,18 Mice lacking NgR1 also show greater experience-dependent plasticity and turnover of synaptic structures in adulthood similar to that observed in juvenile WT mice.19–21 Among fiber tracts regenerating after axotomy is the optic nerve (ON).22

Pharmacologically, all three NgR1 ligands can be blocked with a soluble decoy receptor, NgR1(310)-Fc.22–29 This molecule contains the ligand binding domains fused to the Fc portion of IgG1, and blocks myelin inhibition of neurite outgrowth. Moreover, rat or human NgR1(310)-Fc can be administered intrathecally to induce axonal sprouting and regeneration after spinal cord injury or stroke.17,22,24,26–29 The enhanced anatomical rearrangement after injury leads to greater neurological function even when the protein is administered long after injury.22

One previous study investigated the role of NgR1 after episcleral and limbal vein photocoagulation.30 The investigators reported that intravitreal injection of either anti-NgR1 antibody or a rat NgR1 decoy protein preserved RGC number. We evaluated the potential benefit of human NgR1(310)-Fc for glaucoma. First, we replicated the previous results with rat NgR-Fc, and then we evaluated the human protein. We demonstrated that the protein has a terminal half-life in the vitreal humor of approximately 24 hours after local injection, achieving levels similar to the CNS tissue level associated with greater recovery from spinal cord contusion. Weekly intravitreal injections of human NgR1(310)-Fc promoted axonal regeneration after ON crush, demonstrating effective target engagement. In a microbead glaucoma model, elevated IOP leads to significant loss of RGC retrograde labeling at 4 weeks. Treatment with human NgR1(310)-Fc by vitreal injection fully rescued RGC cell density without changing the IOP. We concluded that local injection of human NgR1(310)-Fc is a candidate therapy for neuroprotection in glaucoma.

Methods

NgR1(310)-Fc Protein Production and Measurement

The production of human NgR1(310)-Fc by expression in a stable CHO-S cell line at Axerion Therapeutics has been described.28 The decoy vector encodes aa residues 1-310 of human NgR1 carrying Cys266Ala and Cys309Ala substitutions, fused to the Fc domain of human IgG1. Stock protein solutions at 10 mg/mL were stable for greater than 1 year at −80°C. Measurement of NgR1(310)-Fc levels in fluid and retinal or ON tissue homogenates used the same ELISA method previously described for CSF and brain tissue.28

Pharmacokinetics of Intravitreal NgR1(310)-Fc

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–250 g, Charles River) were used in this study. All procedures here and throughout were reviewed by the Yale Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and adhered to the procedures of the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Animals were allocated randomly into one of following groups (group number, sample collection time, number of rats): Group 1, 15 minutes, total 8 rats; Group 2, 2 hours, total 8 rats; Group 3, 8 hours, total 8 rats; Group 4, 16 hours, total 8 rats; Group 5, 24 hours, total 8 rats; Group 6, 72 hours, total 12 rats; and Group 7, 180 hours, total 12 rats. In this study, all animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of a mixture of 75 mg/kg ketamine + 5 mg/kg xylazine. After anesthesia, either 5 μL of hIgG-Fc (1 μg/μL) or 5 μL of hNgR1(310)-Fc (1 μg/μL) solution was given by intravitreal injection. At the end of each study point, animals were anesthetized and killed by inhalation of 100% CO2. Both eyes were enucleated and immersed in PBS at 4°C. The ONs were cut and collected in microfuge tubes individually. After ON collection, eyes were dissected, vitreous humor (VH) samples were collected by pipetting into microfuge tubes individually, then retina were isolated, washing three times in ice-cold PBS.

Fluro-Gold (FG) Retrograde Tracing From Colliculus to Retina

Female Sprague Dawley rats (200–250 g; Charles River Laboratories, Frederick, MD, USA) were used. Animals were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane and maintained with 2% isoflurane in an oxygen–air mixture using a gas anesthesia mask in a stereotaxic frame. A burr hole (2 × 2 mm) was made in the skull on each side of the sagittal suture (0.5 mm from both sagittal and transverse sutures). After opening the dura, the cerebral tissue that lies over the superior colliculus (SC) was aspirated gently to avoid rupturing the dural sinus. A thin layer of gelatin sponge presoaked with 6% of Fluro-Gold (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) was placed on the surface of the SC. The burr holes were then filled with Gelfoam, and the skin was sutured with 4.0 Vicryl.

For FG-labeled RGCs counts, the flat-mounted whole retina was divided into four equally-sized quadrants. Four nonoverlapping images were captured from the median line of each quadrant. The total of 16 microscope fields per retina were counted by an automated procedure using the cell counting macro function of ImageJ (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/; provided in the public domain by the National Institutes of Health [NIH], Bethesda, MD, USA). Total FG-labeled RGCs and large FG-labeled RGCs with an area greater than 120 μm2 were scored for ON crush and microbead experiments from Zeiss LSM 710 confocal images. For the vein cauterization experiment, counts of large FG-labeled RGCs were made for those cells with a maximal diameter greater than 15 μm using a wide-field epifluorescence microscope.

Episcleral Vein Cauterization (EVC)

The procedure was performed as described.31 In brief, rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of a cocktail of ketamine (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg). A conjunctival incision was made approximately 2 mm posterior to the limbus at the right eye. After exposure, two dorsal and one temporal episcleral veins were individually lifted with a curved, nonserrated tips forceps and cauterized. The conjunctival incision was sutured, and antibiotic ointment was applied. The IOP was monitored in the untreated and treated left eye of all experimental animals before the EVC procedure (day 0), as well as the postoperative period with the Tonolab rebound tonometer (Colonial Medical Supply, Franconia, NH, USA). All animals were anesthetized for IOP measurements. Four consecutive IOP measurements (of 8–10) were obtained and pooled for calculating a mean IOP value (mm Hg).

ON Crush Injury With Anterograde Axonal Tracing of RGC

Five days after the FG retrograde tracing, rats were reanesthetized with the isoflurane inhalation method described above. A 2-cm incision was made in the skin above the left orbit. The lachrymal glands and extraocular muscles were removed to expose 3 to 4 mm of the ON. The dural sheath surrounding the ON was carefully incised, and the nerve was crushed 2 mm behind the eye with angled jewelers' forceps (#5/45, Dumont Instruments, Vorst, Belgium) for 10 seconds. The surgical site was sutured with 4.0 Vicryl. Nerve injury was verified by the appearance of a clearing at the crush site. Immediately after the ON crush, 5 μg hNgR1(310)-Fc (1 μg/μL) or hIgG-Fc (1 μg/μL) was injected into anterior chamber of the left eye (n = 10 for each group) with a 33-gauge needle. One week after the ON crush and the first intravitreal injection, the same does of hNgR1(310)-Fc or hIgG-Fc was injected intravitreally in the left (injured) eye under the isoflurane inhalation anesthesia described above.

Two weeks after the ON crush, 3 μL of cholera toxin β (CTB), Alexa Fluor 555 conjugated (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were injected into the anterior chamber of both eyes under the isoflurane inhalation anesthesia. Two to 3 days after the CTB injection, animals were deeply anesthetized and then perfused transcardially with PBS, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS (PFA) solution. The total survival time from crush injury to sacrifice was 16 to 17 days. Both eyes were enucleated and the retina was removed. Four equally-spaced radial incisions from the retinal margin approximately two-thirds of the radial length toward the ON head were made on the retina using spring scissors. The flat-mounted whole retina was placed on the microscope slide and was coverslipped with Vectashield mounting medium. The ON was dissected from the eyeball and postfixed in the 4% PFA solution. After clearing the whole nerve by using a clearing procedure adapted from the study of Erturk et al.,32 the sample was mounted on a glass side with a coverslip for imaging.

For ON axon quantification, the ON was imaged by using the Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope. Axons labeled with CTB were counted from the different distances to the crush lesion.

Microbead Model of Increased IOP With Intravitreal hNgR1(310)-Fc

Female Sprague Dawley rats (200 to 250 g, Charles River Laboratories) were used. Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane described above and placed in a stereotaxic frame. The IOP was measured by using a tonometer as above. The baseline IOP was determined from the mean of 6 tonometer readings. After the IOP measurement, 5 μL of a sterile 1 × 106 microbeads/mL solution (approximately 5000 microbeads) of 15-μm diameter polystyrene microbeads conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 chromophore (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) were injected into the anterior chamber. The IOP was measured again 5 days after the microbead injection. Eyes with IOP ≥ 15 mm Hg were included in this experiment and were assigned randomly into two groups. Eyes with IOP < 15 mm Hg were excluded from treatment randomization. Those eyes with elevated IOP received a single intravitreal injection of either 5 μg hNgR1(310)-Fc (1 μg/μL) or hIgG-Fc (1 μg/μL) with a 33-gauge needle. The IOPs then were measured every 7 days afterwards. At 3 weeks after the intravitreal treatment initiated, rats were reanesthetized with isoflurane and bilateral FG retrograde tracing was performed using the method described above. Animals were killed 5 days after the FG tracing. The whole retina was flat-mounted for imaging and cell counting.

Statistics

All data were analyzed with SPSS (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and/or Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) software.

Results

Replication of Rat NgR1(310)-Fc Benefit After EVC

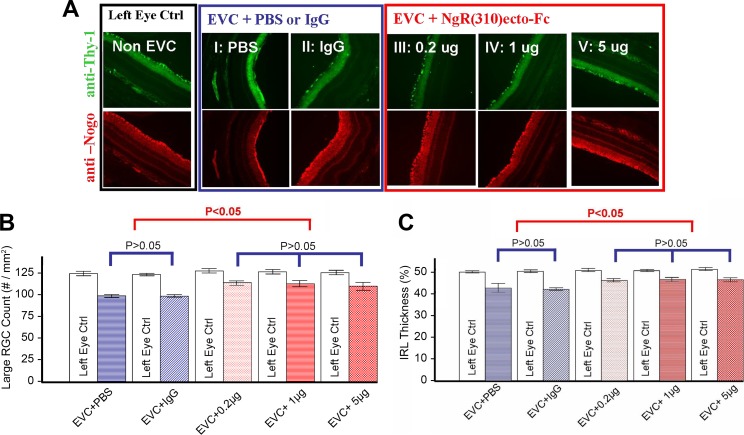

As a first step to evaluate NgR1 decoy for glaucoma, we studied rat EVC (Fig. 1). The IOP in the treated right eye was elevated from baseline 10 to 25 mm Hg by cauterization (not shown). Three dosages of rat NgR1(310)-Fc were injected intravitreally injection (low, 0.2 μg; medium, 1 μg; and high, 5 μg; all n = 6). Two control groups (PBS vehicle and 5 μg rat IgG injection, both n = 6) were used in a double-masked, randomized animal study. Two intravitreal injections were performed, one at day 0 immediately after cauterization and one at day 7. At 7 weeks after injection, we analyzed RGC changes by FG retrograde labeling and immunohistological staining. All left eyes were used as baseline control (no EVC, no treatment). We noted that Nogo-A expression is present in the internal retinal layers and continues to be expressed after cauterization (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

RGC rescue using rat NgR1(310)-Fc after episcleral vein cauterization. (A) Significant RGC loss was observed in all EVC + treatment eyes (I–V) compared to non-EVC left eyes. The RGC loss in NgR1(310)-Fc treatment groups (III–V) is significantly less than control groups (I and II). (B) Large RGC density (per mm2). Significant reductions (P < 0.05) in large RGCs density were observed in EVC eyes versus non-EVC eyes in all groups. The reduction of large RGC in NgR1(310)-Fc treatment groups (III–V) is significantly (P < 0.05) less than in control groups (I and II). (C) Percentage IRL thickness (% IRL/total retina thickness). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and immunohistology staining demonstrate the significant reduction (P < 0.05) of IRL (RGC and inner plexiform layer [IPL]) thickness in EVC + treatment eyes versus the non-EVC eyes. A significant reduction (P < 0.05) IRL thickness occurs in nontreated EVC eyes (I and II) comparing to NgR1(310)-Fc–treated eyes (III–V). Data are mean ± SEM.

In the control groups, there was a 20% decrease in large RGC cell density from 125 to 100 cells/mm2, and there was no difference between PBS and nonimmune IgG injection (Figs. 1A, 1B). The rats treated with rat NgR1(310)-Fc protein, showed significantly greater large RGC density, with mean values of 115 cells/mm2 (Figs. 1A, 1B). Greater counts were observed in all three NgR1(310)-Fc dose groups. In the same samples, the fractional thickness of the inner retinal layer (IRL) was measured (Fig. 1C). For the control groups, the vein cauterization reduced IRL thickness from 50% of the retina to 42%. The degree of decrease was significantly lessened by rat NgR1(310)-Fc, with an average thickness of 46% (Fig. 1C). These data confirmed previous work with this vascular model30 and supported the potential use of NgR1(310)-Fc treatment for glaucoma.

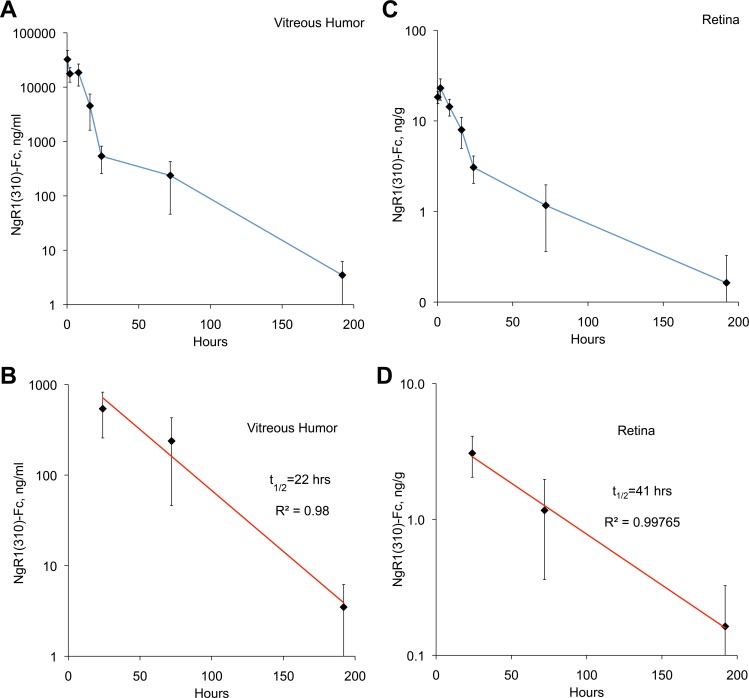

Intravitreal Pharmacokinetics of Human NgR1(310)-Fc

If intravitreal NgR1(310)-Fc is to be considered as glaucoma therapy, then the stability and pharmacokinetics of the human protein must be defined. We monitored single dose kinetics in a series of rats injected with 5 μg of human NgR1(310)-Fc protein. Remaining protein was detected with a sandwich ELISA that detects the NgR1 moiety and the Fc moiety of the fusion protein. The fusion protein levels in the vitreal fluid dropped from a peak of 18,000 ng/mL (240 nM per NgR1(310)-Fc monomer) shortly after injection to 4 ng/mL (by 1 week; Fig. 2A). The decline fit best to a two-component decay with a more rapid decline in the first 24 hours followed by a slower rate thereafter. For the period from 1 to 7 days, the apparent half-life of NgR1(310)-Fc in vitreal humor was 22 hours (Fig. 2B). Between 1 and 7 days, the level of human NgR1(310)-Fc protein varied between 4 and 540 ng/mL (0.02–7 nM). The affinity of NgR1 for its ligands has been measured between 0.4 and 5 nM,33,34 suggesting adequate decoy concentrations. In addition, these levels are similar to those obtained in brain and spinal cord for dosing that promotes recovery from spinal cord injury.28 We also measured retinal protein levels in the same experiments. Similar kinetics, but lower levels of NgR1(310)-Fc protein were observed (Figs. 2C, 2D), suggesting that the protein penetrates a limited distance from the vitreal surface.

Figure 2.

Pharmacokinetics of intravitreal human NgR1(310)-Fc. Rats received a single dose of 5 μg hNgR1(310)-Fc injected in the vitreal humor in 1 μL of saline. Tissue was collected at the indicated times after injection and hNgR1(310)-Fc protein was measured. Data are mean ± SEM for n = 8 rats per time point. (A) The hNgR1(310)-Fc concentration in the vitreous is plotted as a function of time after injection. (B) Data from (A) for 1 to 7 days after injection are replotted on a log scale and fit to an exponential decay curve. (C) The hNgR1(310)-Fc concentration in the retinal tissue is plotted as a function of time after injection. (D) Data from (C) for 1 to 7 days postinjection are replotted on a log scale and fit to an exponential decay curve.

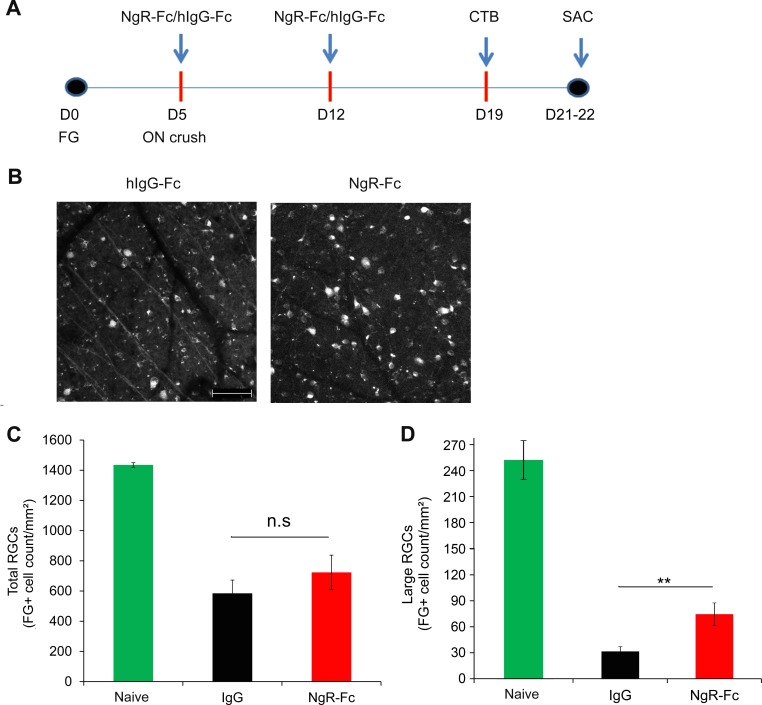

Human NgR1(310)-Fc Efficacy to Promote Axonal Regeneration After ON Crush

The NgR1 protein is best studied with regard to axonal sprouting and regeneration after trauma. Previous genetic studies have demonstrated that NgR1 function limits axonal regeneration after ON crush injury in mice.22 To provide evidence of target engagement, we administered human NgR1(310)-Fc decoy protein to rats immediately after ON crush injury (Fig. 3A). Based on the pharmacokinetic data (Fig. 2), we used a 5 μg dose injected once every 7 days to the vitreal humor. We assessed RGC survival by retrograde FG labeling (Figs. 3B, 3C), and we monitored axonal regeneration by anterograde CTB labeling (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Intravitreal human NgR1(310)-Fc treatment of ON crush. (A) Experimental timeline of hNgR1(310)-Fc intraocular injection in a rat ON crush model. Rats received bilateral RGCs retrograde labeling with 6% FG at Day 0. At day 5 of FG labeling, the left ON was crushed by using a #5/45 Dumont forceps. Right after the ON crush, 5 μL of either hNgR1(310)-Fc or hIgG-Fc (1 μg/μL) was injected into the anterior chamber of the left eye (n = 10 per group). At 1 week after the first intravitreous treatment, the same dose of either hNgR1(310)-Fc or hIgG-Fc was injected into the anterior chamber of the left eye. At 1 week after the second treatment, both eyes received anterograde ON axonal tracing with Alexa Fluor 555 conjugates of CTB. Rats were killed two to three days after the CTB tracing (15 or 16 days after crush injury). (B) Representative images of FG labeled RGCs from the ON crushed eyes of hNgR1(310)-Fc or hIgG-Fc–treated rats. Scale bar: 100 μm. (C) Quantification of FG-labeled RGCs without injury, or after ON crush from hNgR1(310)-Fc or hIgG-Fc–treated groups. The FG-labeled RGC counts were higher in hNgR1(310)-Fc–treated rats compared to the hIgG-Fc–treated rats, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. Data are mean ± SEM (P = 0.18, Student's 2-tailed t-test). (D) The FG-labeled RGCs after axotomy were measured as in (C), except that only large diameter cells (>120 μm2) were measured. Data are mean ± SEM (**P < 0.01, Student's 2-tailed t-test).

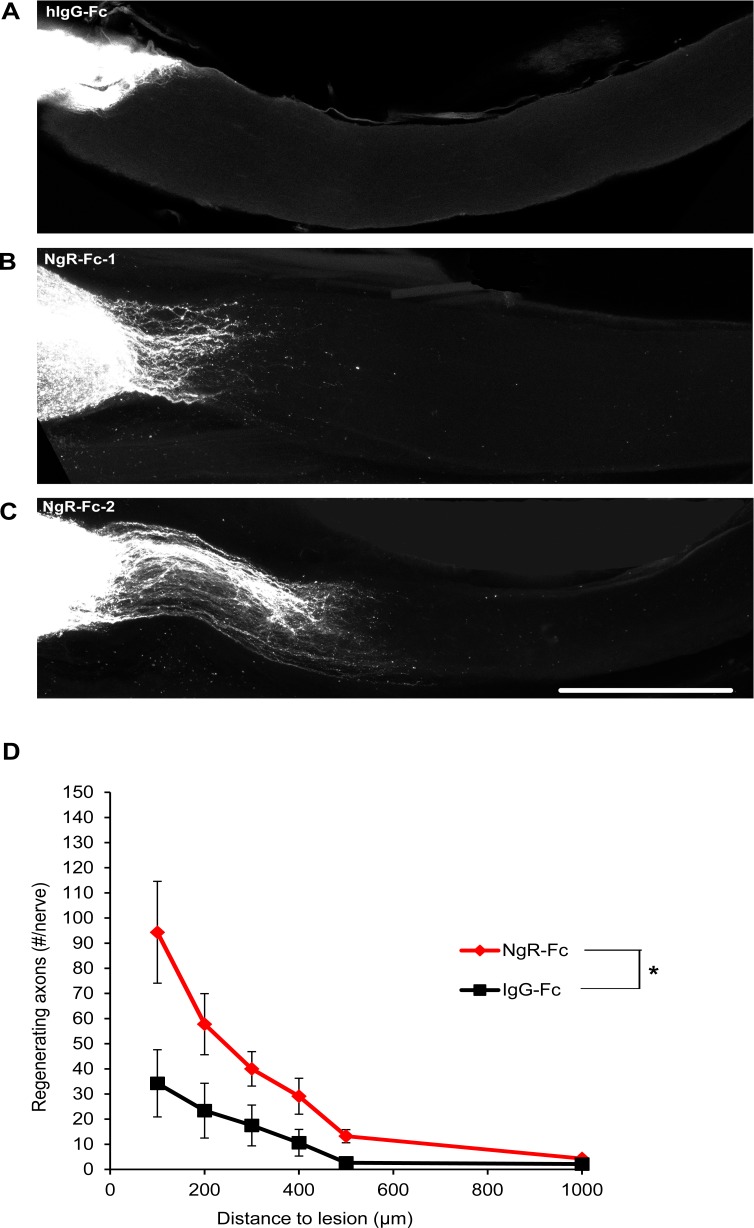

Figure 4.

Increased axonal regeneration after intravitreal human NgR1(310)-Fc. (A) Representative images of ON from two hNgR1(310)-Fc– and one hIgG-Fc–treated rats. The CTB-labeled RGC axons are white. The eye is the left and the brain to the right. Proximal to the crush injury labeling is strong and individual fibers are not visualized. These images are projections of confocal Z stacks through the entire ON. Scale bar: 500 μm. (B) The number of regenerating ON fibers is presented as a function of distance central from the crush site. The number of regenerating axon increased in the NgR-Fc–treated group from 100 to 1000 μm distal to the crush site compared to the hIgG-Fc group. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 9 for the NgR-Fc group and n = 8 for the IgG-Fc group. P < 0.05, by repeated measures ANOVA.

A significant fraction of RGC neurons are known to die after axotomy by ON crush injury.35 In control Fc-treated eyes 19 days after crush injury, FG-prelabeled RGC density was decreased by more than 50% compared to eyes without axotomy (Figs. 3B, 3C and compare to microbead controls below). Treatment with intravitreal human NgR1(310)-Fc showed a nonsignificant trend to reduced RGC loss (Figs. 3B, 3C). By inspection, the effect of human NgR1(310)-Fc treatment appeared most obvious for large diameter RGC cell bodies (Fig. 3B). Therefore, we measured the large (>120 μm2) RGC soma population selectively (Fig. 3D). Human NgR1(310)-Fc treatment significantly increased large RGC cell counts after axotomy by a factor of greater than two.

If intravitreal human NgR1(310)-Fc is blocking NgR1 function in this model, we predict greater axonal regeneration past the crush site. To assess RGC regrowth, we injected the anterograde tracer, CTB, into the vitreal fluid two weeks after the crush injury and imaged traced axons 5 days later (Fig. 4). In control Fc-treated eyes, few axons extend past the crush site in whole mounts of the ON imaged by confocal microcopy after tissue clearing (Fig. 4A). In contrast, with intravitreal human NgR1(310)-Fc treatment, more axons regenerated past the crush site into the distal ON (Figs. 4B, 4C). Counts of regenerating axons at different distances past the injury site revealed significantly greater numbers in the NgR1(310)-Fc–treated group up to 1000 μm past the injury (Fig. 4D). The increase may reflect axon regenerative effects and improved cell survival, but shows that this dose of intravitreal human NgR1(310)-Fc engages relevant targets in the eye.

NgR1(310)-Fc Rescues RGC Survival in Microbead Model of Glaucoma

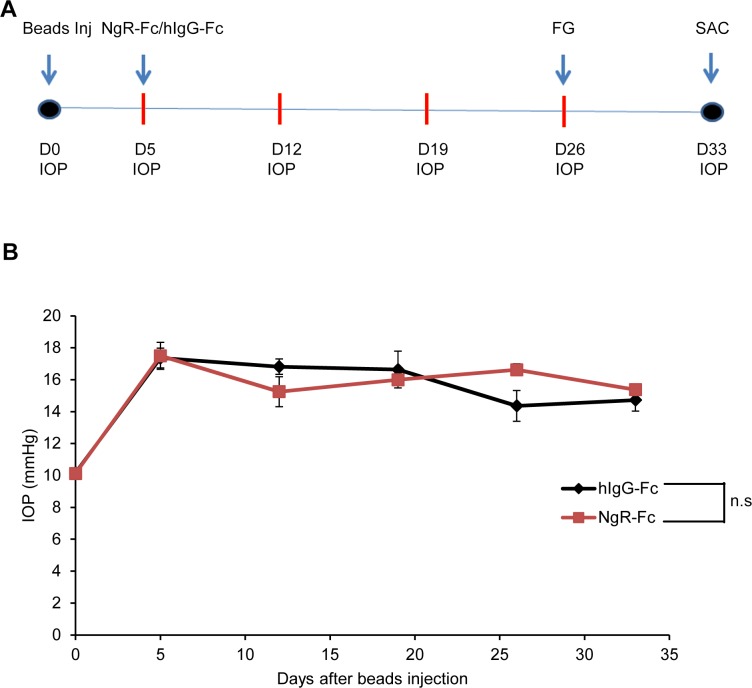

Based on the efficacy of intravitreal human NgR1(310)-Fc to induce axonal regeneration from RGC in the axotomy model, we tested its efficacy to protect RGC survival in a rat model of elevated IOP based on mechanical obstruction of outflow by microbead injection. Delivery of microbeads to the anterior chamber yielded a cohort of rats with persistently elevated pressure (Figs. 5A, 5B). After confirmation increased pressure, animals were randomized to treatment with 5 μg doses of intravitreal human NgR1(310)-Fc, or human IgG-Fc as control. Administration of these doses did not alter IOP, which remained elevated for 4 weeks in this model (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Microbead model of glaucoma and human NgR1(310)-Fc administration. (A) Experimental timeline of hNgR1(310)-Fc intraocular injection in a rat microbeads occlusion glaucoma model. Rats received microbeads injection into the anterior chamber. At day 5 of the injection, eyes with IOP ≥ 15 mm Hg were included in the experiment and divided randomly into two groups (n = 12 per group). Then, 5 μL of either hNgR1(310)-Fc or hIgG-Fc (1 μg/μL) were injected into the anterior chamber. The IOPs were measured once a week afterwards. At day 26 of intraocular treatment, RGCs were retrogradely labeled with 6% FG. Rats were killed 7 days after FG tracing. (B) The hNgR1(310)-Fc treatment does not affect the IOP in the rat microbeads induced ocular hypertension model. The IOPs were measured by using the tonometer before the microbeads injection (day 0), at day 5 (right before the intraocular treatment), and every 7 days after treatment. The IOP is plotted as a function of time. There is no significant difference in IOP between the hNgR1(310)-Fc–treated group and the hIgG-Fc–treated group. Data are mean ± SEM. P > 0.05, by repeated measures ANOVA.

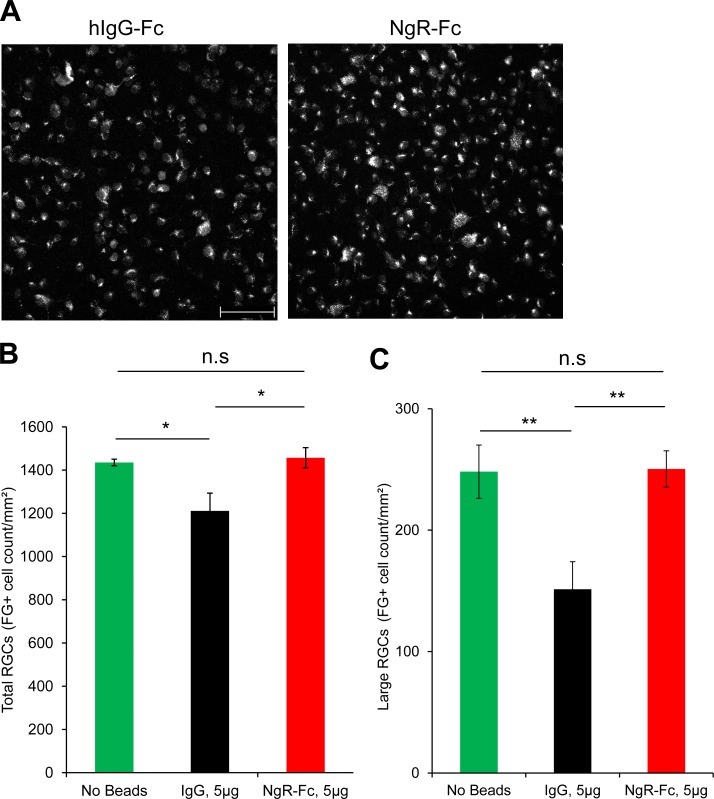

To assess RGC size, survival, and axonal transport, FG was administered to the superior colliculus at 21 days after human NgR1(310)-Fc administration and the rats were killed 5 days later. Cell counts of flat mounted retinae showed that the elevated IOP group treated with IgG-Fc had lost 15% of labeled RGC density (Figs. 6A, 6B). In contrast, there was no loss of FG-labeled cells in the human NgR1(310)-Fc–treated group (Figs. 6A, 6B). We also counted the density of large (>120 μm2) RGC cell bodies (Fig. 6C). Increased IOP resulted in a 40% decrease in this measure, with no loss in the NgR1(310)-Fc–treated group. Thus, intravitreal delivery of NgR1(310)-Fc fully rescued RGC size, survival and/or axonal transport in a rat model of mechanically elevated IOP over 3.5 weeks.

Figure 6.

The RGC preservation by intravitreal human NgR1(310)-Fc in elevated IOP model. (A) Representative images of FG-labeled RGC in retina from hNgR1(310)-Fc–treated and hIgG-Fc-treated animal after microbead IOP elevation. Scale bar: 100 μm. (B) Quantification of FG-labeled RGCs in the microbead occlusion rats after hNgR1(310)-Fc or hIgG-Fc treatment, or rats without microbeads injection. There is significant increase of FG-labeled RGCs in the NgR-Fc–treated group compared to the hIgG-Fc–treated group. The FG-labeled RGCs counts from the NgR-Fc–treated group was similar to naïve rats (no beads). Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, by 1-way ANOVA, Dunnett's multiple comparisons tests. (C) The large (> 120 μm2) FG-labeled RGC counts from the hNgR1(310)-Fc–treated groups were significantly higher than the hIgG-Fc–treated rats, but were similar to the naïve rats (no beads). Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001, by 1-way ANOVA, Dunnett's multiple comparisons tests.

Discussion

Human NgR1(310)-Fc delivered to the vitreal space persists at detectable levels for 7 days. Moreover, it engages targets to promote axonal regeneration after ON crush injury. The NgR1 blocking decoy protein, but not control Fc alone, rescues RGC cell counts fully from elevated IOP over 3.5 weeks in the rat. These data raised the possibility that that intravitreal NgR1(310)-Fc might have use for treatment of glaucoma.

Our data extended initial findings suggesting a benefit of NgR1 blockade beyond trauma in an episcleral vein cauterization experiment.30 We demonstrated the prolonged detection of human NgR1(310)-Fc decoy protein in the vitreous humor after injection, and also a stimulation of axonal regeneration by active protein. Moreover, we provided data from a mechanical IOP model separate from vein cauterization. The bead model avoids toxicity secondary to vascular effects in the cauterization model and provides an independent demonstration of NgR1(310)-Fc efficacy.

The human NgR1(310)-Fc blocking protein does not act by lowering IOP, which was unchanged under conditions in which human NgR1(310)-Fc allowed a full rescue of RGC counts. A separate mode of action also is supported by the ON crush model in which human NgR1(310)-Fc produces axonal regeneration greater than control.

For the microbead model, retrograde labeling with FG was conducted after elevation of IOP. Thus, recovery of RGC density with NgR1(310)-Fc may reflect a rescue of cell death and/or a rescue of IOP-inhibited retrograde axon transport. Alternative labeling schemes would be required to distinguish fully these mechanisms. In any case, the NgR1(310)-Fc treatment returns total labeled RGC counts to normal levels. The loss of RGC counts after axotomy or with IOP is greatest for large diameter RGC, and, hence the NgR1(310)-Fc rescue to control values is most obvious for this class. It is known that cell size influences sensitivity to injury36–38 and that IOP has complicated effects on cell size.39–41 In our studies, the relative selectivity of axotomy and IOP for large RGC counts may reflect cell atrophy after injury with a shift from large to small diameter groups, as well as greater large cell sensitivity to injury-induced death. The pronounced NgR1(310)-Fc rescue of large RGC counts may reflect a trophic effect to increase cell size after injury, shifting smaller cells into this category. Regardless, NgR1(310)-Fc intervention returns the pattern to that observed in healthy eyes.

The molecular basis for NgR1(310)-Fc protection of RGC from elevated IOP will be a subject of further study. In cortical neurons, one study has indicated that human NgR1 acts to restrict neurotrophic signaling by brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF).42 Tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB) agonists are known to enhance RGC survival after axotomy.43 Therefore, blocking NgR1 pathways may allow more efficient neurotrophin signaling to promote axonal regeneration after nerve crush and cell survival in the face of high IOP. Myelin ligands also are known to signal via NgR1 to activate RhoA and Rho-Associated Kinase (ROCK).4,44 The Rho-ROCK pathway can induce neuronal cell death.45 The ROCK inhibitors interrupt the Nogo Receptor signaling pathway,46,47 and have been shown to promote RGC survival and retinal axon growth.48,49 While RGC survival induced by intravitreal human NgR1(310)-Fc is not mediated by reduced IOP, multiple biochemical pathways in neurons are likely to be involved.

In conclusion, intravitreal administration of NgR1(310)-Fc preserves anatomical measurements in several models of rodent RGC damage. The data suggested possible use to modify the chronic course of glaucoma. Further exploration and development are facilitated by the availability of human NgR1(310)-Fc protein.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from NIH-NIMHD (GM, JCT, and SMS), as well as grants from the Research to Prevent Blindness (JCT), and from the NIH-NINDS and Falk Medical Research Trust (SMS).

Disclosure: X. Wang, None; J. Lin, None; A. Arzeno, None; J.Y. Choi, None; J. Boccio, None; E. Frieden, Axerion Therapeutics (E); A. Bhargava, None; G. Maynard, Axerion Therapeutics (E); J.C. Tsai, None; S.M. Strittmatter, Axerion Therapeutics (F, I, C), P

References

- 1. Quigley HA. Glaucoma. Lancet. 2011; 377: 1367–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kingman S. Glaucoma is second leading cause of blindness globally. Bull World Health Organ. 2004; 82: 887–888. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kerrigan-Baumrind LA, Quigley HA, Pease ME, Kerrigan DF, Mitchell RS. Number of ganglion cells in glaucoma eyes compared with threshold visual field tests in the same persons. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000; 41: 741–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schwab ME, Strittmatter SM. Nogo limits neural plasticity and recovery from injury. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2014; 27C: 53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liu BP, Cafferty WB, Budel SO, Strittmatter SM. Extracellular regulators of axonal growth in the adult central nervous system. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006; 361: 1593–1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. GrandPre T, Nakamura F, Vartanian T, Strittmatter SM. Identification of the Nogo inhibitor of axon regeneration as a Reticulon protein. Nature. 2000; 403: 439–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen MS, Huber AB, van der Haar ME, et al. Nogo-A is a myelin-associated neurite outgrowth inhibitor and an antigen for monoclonal antibody IN-1. Nature. 2000; 403: 434–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mukhopadhyay G, Doherty P, Walsh FS, Crocker PR, Filbin MT. A novel role for myelin-associated glycoprotein as an inhibitor of axonal regeneration. Neuron. 1994; 13: 757–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McKerracher L, David S, Jackson DL, Kottis V, Dunn RJ, Braun PE. Identification of myelin-associated glycoprotein as a major myelin-derived inhibitor of neurite growth. Neuron. 1994; 13: 805–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang KC, Koprivica V, Kim JA, et al. Oligodendrocyte-myelin glycoprotein is a Nogo receptor ligand that inhibits neurite outgrowth. Nature. 2002; 417: 941–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fournier AE, GrandPre T, Strittmatter SM. Identification of a receptor mediating Nogo-66 inhibition of axonal regeneration. Nature. 2001; 409: 341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liu BP, Fournier A, GrandPre T, Strittmatter SM. Myelin-associated glycoprotein as a functional ligand for the Nogo-66 receptor. Science. 2002; 297: 1190–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Atwal JK, Pinkston-Gosse J, Syken J, et al. PirB is a functional receptor for myelin inhibitors of axonal regeneration. Science. 2008; 322: 967–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huebner EA, Kim BG, Duffy PJ, Brown RH, Strittmatter SM. A multi-domain fragment of Nogo-A protein is a potent inhibitor of cortical axon regeneration via Nogo receptor 1. J Biol Chem. 2011; 286: 18026–18036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ji B, Li M, Budel S, et al. Effect of combined treatment with methylprednisolone and soluble Nogo-66 receptor after rat spinal cord injury. Eur J Neurosci. 2005; 22: 587–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim JE, Liu BP, Park JH, Strittmatter SM. Nogo-66 receptor prevents raphespinal and rubrospinal axon regeneration and limits functional recovery from spinal cord injury. Neuron. 2004; 44: 439–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee JK, Kim JE, Sivula M, Strittmatter SM. Nogo receptor antagonism promotes stroke recovery by enhancing axonal plasticity. J Neurosci. 2004; 24: 6209–6217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim JE, Li S, GrandPre T, Qiu D, Strittmatter SM. Axon regeneration in young adult mice lacking Nogo-A/B. Neuron. 2003; 38: 187–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Akbik FV, Bhagat SM, Patel PR, Cafferty WB, Strittmatter SM. Anatomical plasticity of adult brain is titrated by Nogo Receptor 1. Neuron. 2013; 77: 859–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McGee AW, Yang Y, Fischer QS, Daw NW, Strittmatter SM. Experience-driven plasticity of visual cortex limited by myelin and Nogo receptor. Science. 2005; 309: 2222–2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang EJ, Lin EW, Hensch TK. Critical period for acoustic preference in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012; 109 (suppl 2): 17213–17220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang X, Duffy P, McGee AW, et al. Recovery from chronic spinal cord contusion after Nogo receptor intervention. Ann Neurol. 2011; 70: 805–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fournier AE, Gould GC, Liu BP, Strittmatter SM. Truncated soluble Nogo receptor binds Nogo-66 and blocks inhibition of axon growth by myelin. J Neurosci. 2002; 22: 8876–8883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li S, Liu BP, Budel S, et al. Blockade of Nogo-66, myelin-associated glycoprotein, and oligodendrocyte myelin glycoprotein by soluble Nogo-66 receptor promotes axonal sprouting and recovery after spinal injury. J Neurosci. 2004; 24: 10511–10520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li S, Kim JE, Budel S, Hampton TG, Strittmatter SM. Transgenic inhibition of Nogo-66 receptor function allows axonal sprouting and improved locomotion after spinal injury. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005; 29: 26–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang X, Baughman KW, Basso DM, Strittmatter SM. Delayed Nogo receptor therapy improves recovery from spinal cord contusion. Ann Neurol. 2006; 60: 540–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang X, Hasan O, Arzeno A, Benowitz LI, Cafferty WB, Strittmatter SM. Axonal regeneration induced by blockade of glial inhibitors coupled with activation of intrinsic neuronal growth pathways. Exp Neurol. 2012; 237: 55–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang X, Yigitalani K, Kim CY, et al. Human NgR-Fc decoy protein via lumbar intrathecal bolus administration enhances recovery from rat spinal cord contusion. J Neurotrauma. 2014; 31: 1955–1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Harvey PA, Lee DH, Qian F, Weinreb PH, Frank E. Blockade of Nogo receptor ligands promotes functional regeneration of sensory axons after dorsal root crush. J Neurosci. 2009; 29: 6285–6295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fu QL, Liao XX, Li X, et al. Soluble Nogo-66 receptor prevents synaptic dysfunction and rescues retinal ganglion cell loss in chronic glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 8374–8380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tsai JC, Wu L, Worgul B, Forbes M, Cao J. Intravitreal administration of erythropoietin and preservation of retinal ganglion cells in an experimental rat model of glaucoma. Curr Eye Res. 2005; 30: 1025–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Erturk A, Becker K, Jahrling N, et al. Three-dimensional imaging of solvent-cleared organs using 3DISCO. Nat Protoc. 2012; 7: 1983–1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hu F, Liu BP, Budel S, et al. Nogo-A interacts with the Nogo-66 receptor through multiple sites to create an isoform-selective subnanomolar agonist. J Neurosci. 2005; 25: 5298–5304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lauren J, Hu F, Chin J, Liao J, Airaksinen MS, Strittmatter SM. Characterization of myelin ligand complexes with neuronal Nogo-66 receptor family members. J Biol Chem. 2007; 282: 5715–5725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moore DL, Goldberg JL. Four steps to optic nerve regeneration. J Neuroophthalmol. 2010; 30: 347–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mey J, Thanos S. Intravitreal injections of neurotrophic factors support the survival of axotomized retinal ganglion cells in adult rats in vivo. Brain Res. 1993; 602: 304–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Luo XG, Chiu K, Lau FH, Lee VW, Yung KK, So KF. The selective vulnerability of retinal ganglion cells in rat chronic ocular hypertension model at early phase. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2009; 29: 1143–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Filippopoulos T, Danias J, Chen B, Podos SM, Mittag TW. Topographic and morphologic analyses of retinal ganglion cell loss in old DBA/2NNia mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006; 47: 1968–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hernandez M, Urcola JH, Vecino E. Retinal ganglion cell neuroprotection in a rat model of glaucoma following brimonidine, latanoprost or combined treatments. Exp Eye Res. 2008; 86: 798–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Urcola JH, Hernandez M, Vecino E. Three experimental glaucoma models in rats: comparison of the effects of intraocular pressure elevation on retinal ganglion cell size and death. Exp Eye Research. 2006; 83: 429–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Prilloff S, Noblejas MI, Chedhomme V, Sabel BA. Two faces of calcium activation after optic nerve trauma: life or death of retinal ganglion cells in vivo depends on calcium dynamics. Eur J Neurosci. 2007; 25: 3339–3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Raiker SJ, Lee H, Baldwin KT, Duan Y, Shrager P, Giger RJ. Oligodendrocyte-myelin glycoprotein and Nogo negatively regulate activity-dependent synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2010; 30: 12432–12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hu Y, Cho S, Goldberg JL. Neurotrophic effect of a novel TrkB agonist on retinal ganglion cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010; 51: 1747–1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schmandke A, Schmandke A, Strittmatter SM. ROCK. and Rho: biochemistry and neuronal functions of Rho-associated protein kinases. Neuroscientist. 2007; 13: 454–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dubreuil CI, Winton MJ, McKerracher L. Rho activation patterns after spinal cord injury and the role of activated Rho in apoptosis in the central nervous system. J Cell Biol. 2003; 162: 233–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Duffy P, Schmandke A, Schmandke A, et al. Rho-associated kinase II (ROCKII) limits axonal growth after trauma within the adult mouse spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2009; 29: 15266–15276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fournier AE, Takizawa BT, Strittmatter SM. Rho kinase inhibition enhances axonal regeneration in the injured CNS. J Neurosci. 2003; 23: 1416–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kitaoka Y, Kitaoka Y, Kumai T, et al. Involvement of RhoA and possible neuroprotective effect of fasudil, a Rho kinase inhibitor, in NMDA-induced neurotoxicity in the rat retina. Brain Res. 2004; 1018: 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sagawa H, Terasaki H, Nakamura M, et al. A novel ROCK inhibitor, Y-39983, promotes regeneration of crushed axons of retinal ganglion cells into the optic nerve of adult cats. Exp Neurol. 2007; 205: 230–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]