Abstract

Background

Increased physical fitness is protective against cardiovascular disease. We hypothesized that increased fitness would be inversely associated with hypertension.

Methods and Results

We examined the association of fitness with prevalent and incident hypertension in 57 284 participants from The Henry Ford ExercIse Testing (FIT) Project (1991–2009). Fitness was measured during a clinician‐referred treadmill stress test. Incident hypertension was defined as a new diagnosis of hypertension on 3 separate consecutive encounters derived from electronic medical records or administrative claims files. Analyses were performed with logistic regression or Cox proportional hazards models and were adjusted for hypertension risk factors. The mean age overall was 53 years, with 49% women and 29% black. Mean peak metabolic equivalents (METs) achieved was 9.2 (SD, 3.0). Fitness was inversely associated with prevalent hypertension even after adjustment (≥12 METs versus <6 METs; OR: 0.73; 95% CI: 0.67, 0.80). During a median follow‐up period of 4.4 years (interquartile range: 2.2 to 7.7 years), there were 8053 new cases of hypertension (36.4% of 22 109 participants without baseline hypertension). The unadjusted 5‐year cumulative incidences across categories of METs (<6, 6 to 9, 10 to 11, and ≥12) were 49%, 41%, 30%, and 21%. After adjustment, participants achieving ≥12 METs had a 20% lower risk of incident hypertension compared to participants achieving <6 METs (HR: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.72, 0.89). This relationship was preserved across strata of age, sex, race, obesity, resting blood pressure, and diabetes.

Conclusions

Higher fitness is associated with a lower probability of prevalent and incident hypertension independent of baseline risk factors.

Keywords: cohort, fitness, hypertension, metabolic equivalents, physical activity

Introduction

Hypertension is highly prevalent, affecting >33% of adults in the United States alone.1 In 2008, hypertension was the most commonly diagnosed medical condition in the United States.2 Hypertension is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease and mortality,3 such that blood pressure reduction has been a major focus of primary prevention efforts.4

Numerous cross‐sectional studies have described a relationship between reduced fitness and blood pressure or hypertension.5–9 Furthermore, large cohort studies have demonstrated that low fitness precedes new‐onset hypertension10–18 even in normotensive populations,19–20 and among persons with an elevated risk for hypertension.21 Nevertheless, few studies13 have examined the effect of demographic factors (age, sex, race) or common comorbidities (obesity, diabetes) on the association between direct measures of fitness and risk for hypertension. Furthermore, few studies have been conducted in a clinical setting.

The purpose of this study was to (1) describe the association between physical fitness and prevalent hypertension at the time of stress testing at baseline; (2) examine the prospective relationship between physical fitness and incident hypertension among participants without hypertension at the time of stress testing at baseline; and (3) to examine whether the prospective relationship between physical fitness and incident hypertension differed across demographic or hypertension risk factors. We hypothesized that a higher level of fitness would be inversely associated with both prevalent and incident hypertension, independent of hypertension risk factors.

Methods

Study Population

The Henry Ford ExercIse Testing Project (The FIT Project) includes 69 885 patients who underwent physician‐referred treadmill stress testing at Henry Ford Health System Affiliated Subsidiaries in metropolitan Detroit, MI between 1991 and 2009. Study details are described elsewhere.22 In brief, patients were excluded from the study population if they were <18 years old at the time of stress testing or if the testing protocol was not the standard Bruce protocol. Among the 69 885 included in our study population, we further excluded patients who had a history of coronary artery disease (N=10 190), or a history of congestive heart disease (N=877) as well as patients missing relevant covariate data (N=1534). Known coronary artery disease was defined as an existing history of any of the following: myocardial infarction, coronary angioplasty, coronary artery bypass surgery, or documented obstructive coronary artery disease on angiogram. Congestive heart failure was defined as prior clinical diagnosis of systolic or diastolic heart failure.

After exclusions, our analytic sample included 35 175 patients with a history of hypertension and 22 109 patients without a history of hypertension. The FIT project was approved by the Henry Ford Hospital Institutional Review Board. Study participants provided informed consent.

Treadmill Stress Testing and Metabolic Equivalents

All patients underwent routine clinical treadmill stress testing using the standard Bruce protocol. The treadmill test was symptom‐limited and was terminated if the patient had exercise‐limiting chest pain, shortness of breath, or other symptoms as assessed by the supervising clinician independent of the achieved heart rate. In accordance with American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology guidelines, testing could be terminated early at the discretion of the supervising clinician for significant arrhythmias, abnormal hemodynamic responses, diagnostic ST‐segment changes, or if the participant was unwilling or unable to continue.

Participants were asked to rest for few minutes prior to the start of the stress test. A single resting blood pressure was obtained in the seated position just prior to the start of exercise. Both standard and large cuff sizes were available as needed. Resting heart rate was also assessed and based on the age‐predicted maximal heart rate formula: 220 – age. Physical fitness, expressed in metabolic equivalents (METs), was based on the workload derived from the maximal speed and grade achieved during the total treadmill time. METs results were categorized into 4 groups based on distribution of the data as follows: <6, 6 to 9, 10 to 11, and ≥12 METs.

Primary Outcomes: Prevalent and Incident Hypertension

Prevalent hypertension was defined as a prior diagnosis of hypertension, use of antihypertensive medications, or an electronic medical record (EMR) problem list‐based diagnosis of hypertension at the time of stress testing (study baseline).

Incident hypertension was ascertained among participants without hypertension at baseline by search of the EMR as well as through linkage with administrative claims files from services delivered by the affiliated group practice or reimbursed by the health plan. A new diagnosis was considered present when a diagnosis of hypertension (ICD‐9 401.XX), was listed in at least 3 separate encounters. Time‐to‐incident hypertension was based on the time between treadmill testing and the date of the first encounter. Patients were censored at their last contact with the integrated Henry Ford Health System group practice when ongoing coverage with the health plan could no longer be confirmed.

Other Measurements

Nurses and/or exercise physiologists collected all data immediately prior to the stress test. Age, sex, and race were assessed via self‐report. Risk factors were defined and gathered prospectively by self‐report, and then augmented by a retrospective search of the EMR. Current smoking was defined as actively smoking at the time of stress testing. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a prior diagnosis of diabetes, use of antihyperglycemic medications including insulin, or an EMR, problem list‐based diagnosis of diabetes. Dyslipidemia was defined by prior diagnosis of any major lipid abnormality, use of lipid‐lowering medications, or EMR, problem list‐based diagnosis of hypercholesterolemia or dyslipidemia. Obesity was defined by self‐report and/or assessment by the clinician historian. Family history of coronary artery disease in a first‐degree relative was based on self‐report. Physical activity was assessed informally via survey question, which asked participants if they regularly exercised (yes or no).

In all cases, complete medication use history was collected prior to the stress test. Medication use was then retrospectively verified and supplemented using the EMR, as well as pharmacy claims files from enrollees in the health system's integrated health plan. Medications were categorized as β‐blockers, lipid‐lowering medications, or medications for lung disease.

Indication for stress test referral was provided by the referring physician, and subsequently categorized into common indications (chest pain, shortness of breath, “rule out” ischemia, or other).

Statistical Analysis

Means and proportions of the study population were calculated for study participants with prevalent hypertension and study participants without prevalent hypertension (overall and in categories of METs). Logistic regression models were utilized to evaluate the cross‐sectional association between METs (in categories and as a continuous variable) and prevalent hypertension at the time of stress testing at baseline. Models were nested. Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, and race (white, black, other). Model 2 was adjusted for Model 1 covariates as well as history of diabetes, history of hyperlipidemia, lipid‐lowering medication use, history of obesity, family history of coronary heart disease, current smoking status, pulmonary disease medication use, and indication for stress testing. Model 3 was adjusted for covariates of Model 2 and resting systolic blood pressure, resting diastolic blood pressure, and percent of maximal heart rate achieved. Further, we plotted the unadjusted probability of hypertension at baseline (ie, prevalent hypertension) across METs.

We used Cox proportional hazards models to examine the association between fitness and incident hypertension among participants without a diagnosis of hypertension at baseline. We employed the same Models 1 to 3 as utilized in the cross‐sectional analysis. A Kaplan‐Meier cumulative incidence plot was used to depict the crude relationship between categories of METs and incident hypertension. We also plotted a restricted cubic spline model (relative to a METs value of 6) to visualize the continuous relationship between METs and incident hypertension after adjustment for covariates.

We assessed for effect modification in strata of age (<40, 40 to 49, 50 to 59, ≥60), sex, race (black, white, other), history of obesity, normotensive resting blood pressure (defined as a resting systolic blood pressure <120 mm Hg and a resting diastolic blood pressure <80 mm Hg), and history of diabetes. These findings were presented as a forest plot. Strata were compared via Wald χ2 testing, which was used to evaluate whether interaction terms were statistically significant additions to the models. Finally, we conducted sensitivity analyses, excluding from our prospective analysis (1) those participants who had a baseline resting systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg, and (2) participants taking pulmonary disease medications. Further, in addition to the forest plot, we repeated our primary analysis in strata of sex. Finally, we performed a sensitivity analysis adjusting for self‐reported sedentary lifestyle.

All analyses were performed with STATA version 11.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). Statistical significance was defined as P≤0.05, using 2‐tailed tests.

Results

Population Characteristics

Participants with hypertension at baseline had an average age of 56 years (Table 1). They were 50% women and 34% black. The most common indications for stress testing were chest pain (56%), “rule out” ischemia (12%), and shortness of breath (9%). The average age among participants without hypertension at baseline was 49 years. These participants were 46% women and 20% black. The most common indications for stress testing were the same: chest pain (48%), “rule out” ischemia (10%), and shortness of breath (8%).

Table 1.

Baseline Population Characteristics by Metabolic Equivalents (METs), Mean (SD) or %

| Characteristics | Prevalent Cases of Hypertension at Baseline | Participants Without Diagnosed Hypertension at Baseline | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N=35 175) | Overall (N=22109) | <6 METs (N=1229) | 6 to 9 METs (N=4171) | 10 to 11 METs (N=8996) | ≥12 METs (N=7713) | P across METs* | |

| Age, y | 56.4 (12.1) | 48.5 (11.8) | 61.4 (13.4) | 54.4 (11.8) | 48.5 (10.4) | 43.3 (9.9) | <0.001 |

| Female, % | 50.2 | 46.0 | 65.9 | 67.6 | 53 | 22.9 | <0.001 |

| Race, % | |||||||

| White | 59.9 | 71.0 | 65.5 | 67.8 | 70 | 74.8 | <0.001 |

| Black | 33.9 | 20.4 | 28.8 | 24.5 | 21.8 | 15.2 | <0.001 |

| Other | 6.2 | 8.6 | 5.7 | 7.8 | 8.3 | 10 | <0.001 |

| History of diabetes, % | 24.4 | 7.9 | 14.9 | 11.7 | 8.2 | 4.4 | <0.001 |

| History of hyperlipidemia, % | 49.0 | 33.4 | 30.8 | 35.7 | 34.6 | 31.1 | 0.001 |

| History of obesity, % | 27.3 | 16.4 | 21.5 | 27.0 | 19.1 | 6.8 | <0.001 |

| Family history of coronary heart disease, % | 51.1 | 52.0 | 46.1 | 51.6 | 53.2 | 51.8 | 0.03 |

| Lipid‐lowering medication use, % | 26.1 | 10.4 | 11.8 | 13.6 | 10.7 | 8.0 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes medication use, % | 11.4 | 2.9 | 6.4 | 5.0 | 2.8 | 1.2 | <0.001 |

| Aspirin use, % | 21.2 | 10.8 | 18.1 | 13.3 | 10.6 | 8.6 | <0.001 |

| Lung disease medication use, % | 9.6 | 7.9 | 15.2 | 9.1 | 8.0 | 5.8 | <0.001 |

| Current smoking status, % | 41.7 | 41.1 | 43.4 | 44.6 | 43.0 | 36.7 | <0.001 |

| Reason for stress test, % | |||||||

| Chest pain | 48.2 | 55.7 | 49.8 | 56.3 | 57.1 | 54.6 | 0.62 |

| Shortness of breath | 9.2 | 8.4 | 11.1 | 8.4 | 8.1 | 8.4 | 0.06 |

| Rule out ischemia | 11.6 | 10.1 | 10.3 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 0.88 |

| Other | 31.0 | 25.9 | 28.8 | 25.2 | 24.8 | 27.0 | 0.46 |

| METs achieved, units | 8.5 (2.9) | 10.3 (2.7) | 4.3 (1.1) | 7.0 (0.2) | 10.0 (0.0) | 13.3 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| Achieved a heart rate of 85% | 74.3 | 90.7 | 66.7 | 82.9 | 92.5 | 96.7 | <0.001 |

| % Heart rate achieved, mean % | 89.2 (10.9) | 93.0 (7.8) | 88.3 (13.1) | 91.2 (8.6) | 92.9 (7.0) | 94.8 (6.4) | <0.001 |

| Resting systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 135.2 (18.9) | 124.2 (16.5) | 133.6 (19.8) | 127.9 (17.7) | 123.3 (15.9) | 121.7 (15.0) | <0.001 |

| Resting diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 82.6 (10.5) | 78.7 (9.8) | 80.2 (10.4) | 79.3 (9.9) | 78.5 (9.7) | 78.3 (9.7) | <0.001 |

P‐values for trends across METs determined via linear and logistic regression.

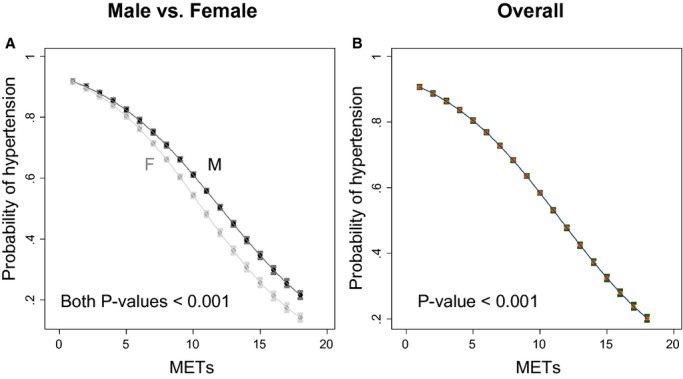

Prevalent Hypertension

Higher fitness was significantly associated with a lower probability of having a diagnosis of hypertension at baseline (P‐trend <0.001). In fact, among participants with METs <6, the probability of hypertension was >70% versus <50% among those with METs ≥12 (Figure 1). Further, participants achieving METs ≥12 during stress testing had a 27% lower odds of having a diagnosis of hypertension at baseline compared to participants achieving a METs level <6 (OR: 0.73; 95% CI: 0.67, 0.80), even after adjustment for hypertension risk factors including resting systolic and diastolic blood pressure (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Probability (95% CI) of participants having hypertension across the range of peak metabolic equivalents (METs) values: (A) by sex and (B) overall.

Table 2.

Association Between Peak Metabolic Equivalents (METs) Achieved and Baseline Hypertension (Odds Ratios, 95% CI), N=57 284

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Categories of fitness (METs) | |||

| <6 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| 6 to 9 | 0.73 (0.68, 0.79) | 0.71 (0.66, 0.77) | 0.88 (0.81, 0.95) |

| 10 to 11 | 0.48 (0.45, 0.52) | 0.52 (0.49, 0.56) | 0.77 (0.72, 0.84) |

| ≥12 | 0.33 (0.30, 0.36) | 0.41 (0.38, 0.44) | 0.73 (0.67, 0.80) |

| P‐trend across categories as ordinal variable | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| METS per 1 unit | 0.88 (0.87, 0.89) | 0.91 (0.90, 0.91) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Model 1: Adjusted for age, sex, and race. Model 2: Model 1 + history of diabetes, history of hyperlipidemia, lipid‐lowering medication use, history of obesity, family history of coronary heart disease, current smoking status, pulmonary medication use, and indication for stress testing. Model 3: Model 2 + resting systolic blood pressure, resting diastolic blood pressure, and % of maximal heart rate achieved.

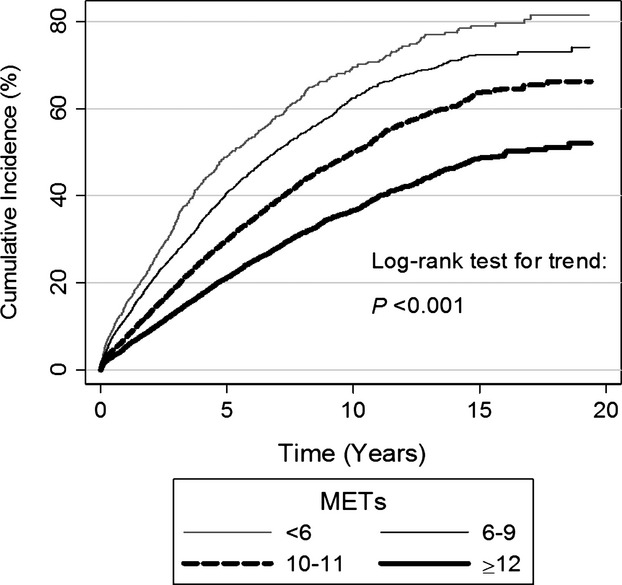

Incident Hypertension

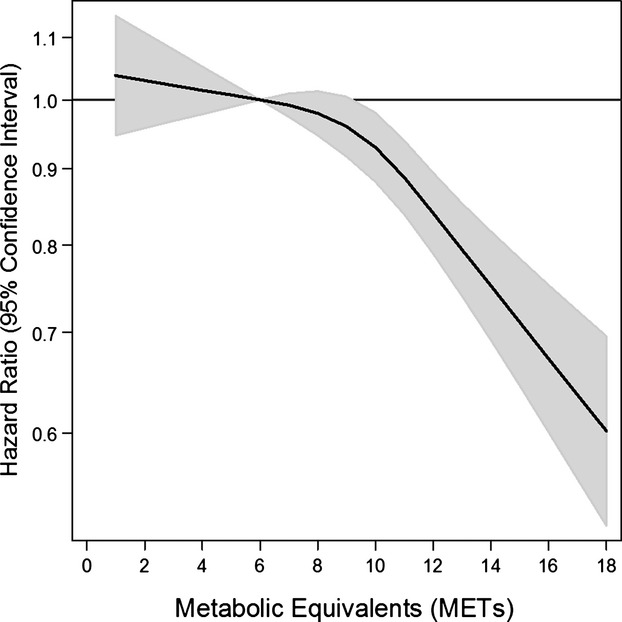

Over a median follow‐up period of 4.4 years (interquartile range: 2.2 to 7.7 years), there were 8053 new cases of hypertension among those without a prior history of hypertension (N=22 109). The unadjusted 5‐year cumulative incidences across categories of METs (<6, 6 to 9, 10 to 11, and ≥12) were 49%, 41%, 30%, and 21%, respectively (Figure 2 for Kaplan‐Meier cumulative incidence plot). There was a significant association between categories of METs and risk of incident hypertension after adjustment for demographic characteristics (Model 1, P‐trend <0.001) (Table 3). This trend was attenuated, but still significant after adjustment for hypertension risk factors, including resting systolic and diastolic blood pressure (Models 2 and 3; P‐trends <0.001). Compared with participants achieving <6 METs, participants achieving ≥12 METs had a 20% lower risk of incident hypertension even after full adjustment (Model 3 hazard ratio: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.72, 0.89). We observed an inverse, nonlinear relationship between baseline MET achievement and subsequent risk of diagnosed hypertension. This association was greatest when MET achievement was >10 (Figure 3). While we initially performed the prospective analysis modeling METs as a continuous variable and found a significant, inverse relationship, these results were ultimately removed upon discovery that the relationship between METs and incident hypertension was nonlinear.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of incident hypertension by category of metabolic equivalents (METs) achieved.

Table 3.

Association Between Peak Metabolic Equivalents (METs) Achieved and Incident Hypertension Among Participants Without Hypertension at Baseline (Hazard Ratios, 95% CI), N=22 109

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Categories of fitness (METs) | |||

| <6 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| 6 to 9 | 0.98 (0.90, 1.07) | 0.97 (0.89, 1.06) | 1.02 (0.93, 1.12) |

| 10 to 11 | 0.83 (0.76, 0.90) | 0.85 (0.77, 0.93) | 0.93 (0.85, 1.02) |

| ≥12 | 0.65 (0.59, 0.72) | 0.70 (0.63, 0.77) | 0.80 (0.72, 0.89) |

| P‐trend across categories as ordinal variable | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Model 1: Adjusted for age, sex, and race. Model 2: Model 1 + history of diabetes, history of hyperlipidemia, lipid‐lowering medication use, history of obesity, family history of coronary heart disease, current smoking status, pulmonary medication use, and indication for stress testing. Model 3: Model 2 + resting systolic blood pressure, resting diastolic blood pressure, and % of maximal heart rate achieved.

Figure 3.

Adjusted hazard ratios (solid line) from a restricted cubic spline model for incident hypertension using categories of baseline peak metabolic equivalents (METs). Shaded region represents the 95% CIs. The models were expressed relative to a METs value of 6 (the reference value) with knots specified at METs values of 6, 10, and 12. Model was adjusted for age, sex, race, history of diabetes, history of hyperlipidemia, lipid‐lowering medication use, history of obesity, family history of coronary heart disease, current smoking status, pulmonary medication use, indication for stress testing, resting systolic blood pressure, and resting diastolic blood pressure. The hazard ratios are shown on a natural log scale.

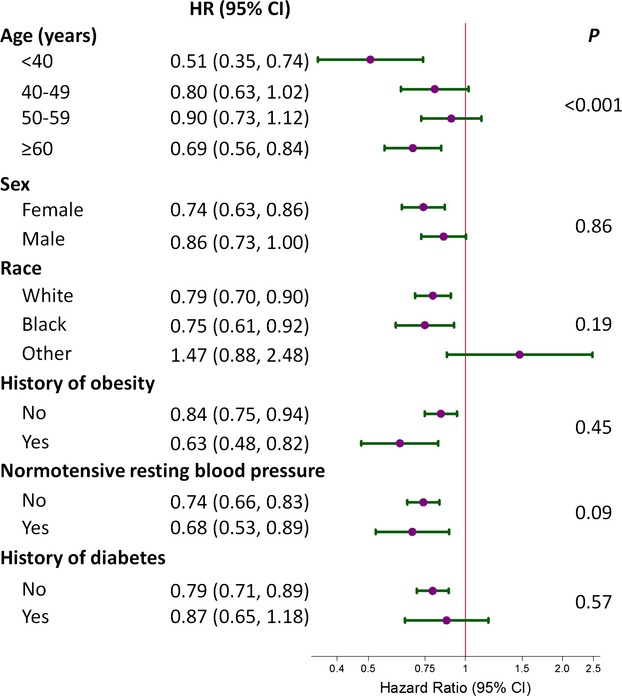

Effect Modification and Sensitivity Analyses

We assessed for effect modification of the relationship between METs and incident hypertension by strata of hypertension risk factors and found significant interactions across strata of age, but not across strata of sex, race, obesity, resting blood pressure, or diabetes (Figure 4). Further, we conducted a sensitivity analysis, excluding from our prospective analysis participants with a resting systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg. Our results were virtually identical (Table 4). A sensitivity analysis, excluding participants on pulmonary disease medications, also did not significantly change our findings (Table 5). In addition, a more detailed examination by sex revealed no difference in the association between fitness and incident hypertension overall (Table 6). Finally, adjustment for physical activity had no impact on our findings (Table 7).

Figure 4.

Forest plot portraying the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI of the association between metabolic equivalents (≥12 METs vs <6 METs) and incident hypertension. Strata were age (<40, 40 to 49, 50 to 59, ≥60), sex (female or male), race (white, black, or other), obese (yes or no), normotensive resting blood pressure (defined as a resting systolic blood pressure <120 mm Hg and a resting diastolic blood pressure <80 mm Hg), or diabetes (no or yes). In general, all models were adjusted for age, sex, race, history of diabetes, history of hyperlipidemia, lipid‐lowering medication use, history of obesity, family history of coronary heart disease, current smoking status, pulmonary medication use, indication for stress testing, resting systolic blood pressure, and resting diastolic blood pressure. In strata of age, the age variable was replaced with a simplified variable <40, 40 to 49, 50 to 59, ≥60). P‐values were determined via the F‐statistic for interaction terms between all strata and categories of METs (METs categories in the 7 to 9 and 10 to 11 range are not shown).

Table 4.

Association Between Peak Metabolic Equivalents (METs) Achieved and Incident Hypertension Among Participants Without Hypertension at Baseline (Hazard Ratios, 95% CI), Restricted to Patients With a Resting Systolic Blood Pressure <140 mm Hg and a Resting Diastolic Blood Pressure <90 mm Hg (N=16 299)

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Categories of fitness (METs) | |||

| <6 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| 6 to 9 | 1.00 (0.88, 1.14) | 1.00 (0.88, 1.13) | 0.99 (0.87, 1.13) |

| 10 to 11 | 0.85 (0.75, 0.96) | 0.89 (0.78, 1.01) | 0.89 (0.78, 1.02) |

| ≥12 | 0.66 (0.58, 0.76) | 0.73 (0.63, 0.84) | 0.74 (0.64, 0.86) |

| P‐trend across categories as ordinal variable | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Model 1: Adjusted for age, sex, and race. Model 2: Model 1 + history of diabetes, history of hyperlipidemia, lipid‐lowering medication use, history of obesity, family history of coronary heart disease, current smoking status, pulmonary medication use, and indication for stress testing. Model 3: Model 2 + resting systolic blood pressure, resting diastolic blood pressure, and % of maximal heart rate achieved.

Table 5.

Association Between Metabolic Equivalents Achieved and Incident Hypertension Among Participants Without Hypertension at Baseline, Excluding Participants Using Medications for Pulmonary Disease (Hazard Ratios, 95% CI), N=20 372

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Categories of fitness | |||

| <6 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| 6 to 10 | 1.00 (0.91, 1.10) | 0.99 (0.90, 1.09) | 1.03 (0.94, 1.14) |

| 10 to 12 | 0.85 (0.77, 0.94) | 0.87 (0.79, 0.96) | 0.96 (0.87, 1.06) |

| >12 | 0.67 (0.60, 0.75) | 0.71 (0.64, 0.79) | 0.82 (0.73, 0.92) |

| P‐trend across categories as ordinal variable | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Model 1: Adjusted for age, sex, and race. Model 2: Model 1 + history of diabetes, history of hyperlipidemia, lipid‐lowering medication use, history of obesity, family history of coronary heart disease, current smoking status, and indication for stress testing. Model 3: Model 2 + resting systolic blood pressure, resting diastolic blood pressure, and % of maximal heart rate achieved.

Table 6.

Association Between Metabolic Equivalents Achieved and Incident Hypertension Among Participants Without Hypertension at Baseline (Hazard Ratios, 95% CI), by Sex

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Women (N=10 164) | Men (N=11 945) | |

| Categories of fitness | ||

| <6 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| 6 to 10 | 1.00 (0.89, 1.12) | 1.05 (0.90, 1.22) |

| 10 to 12 | 0.91 (0.81, 1.03) | 0.96 (0.83, 1.12) |

| >12 | 0.74 (0.63, 0.86) | 0.86 (0.73, 1.00) |

| P‐trend across categories as ordinal variable | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Model adjusted for age, race, history of diabetes, history of hyperlipidemia, lipid‐lowering medication use, history of obesity, family history of coronary heart disease, current smoking status, pulmonary medication use, indication for stress testing, resting systolic blood pressure, resting diastolic blood pressure, and % of maximal heart rate achieved.

Table 7.

Association Between Metabolic Equivalents Achieved and Incident Hypertension Among Participants Without Hypertension at Baseline (Hazard Ratios, 95% CI) With Adjustment for Sedentary Lifestyle, N=22 109

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Categories of fitness | |||

| <6 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| 6 to 10 | 0.98 (0.90, 1.07) | 0.97 (0.89, 1.06) | 1.02 (0.93, 1.12) |

| 10 to 12 | 0.83 (0.76, 0.90) | 0.85 (0.77, 0.93) | 0.94 (0.85, 1.03) |

| >12 | 0.65 (0.59, 0.72) | 0.70 (0.63, 0.77) | 0.81 (0.73, 0.90) |

| P‐trend across categories as ordinal variable | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Model 1: Adjusted for age, sex, and race. Model 2: Model 1 + history of diabetes, history of hyperlipidemia, lipid‐lowering medication use, history of obesity, family history of coronary heart disease, current smoking status, pulmonary medication use, indication for stress testing, and sedentary lifestyle. Model 3: Model 2 + resting systolic blood pressure, resting diastolic blood pressure, and % of maximal heart rate achieved.

Discussion

This study represents one of the largest cross‐sectional and longitudinal studies on the association between fitness and hypertension. Higher fitness was strongly associated with a lower prevalence of hypertension at baseline. Furthermore, among participants with no baseline hypertension, increased fitness demonstrated a strong, inverse relationship with incident hypertension. These associations were observed regardless of demographic characteristics and common hypertension risk factors.

A number of studies have described a cross‐sectional association between fitness and hypertension.5–7 Others have further demonstrated that low fitness was inversely associated with the risk of developing hypertension.10–15 One study evaluated fitness among 4487 young adults from the general population using a Balke protocol treadmill test. They found that after adjustment for hypertension risk factors, including obesity, low fitness (<20th percentile) compared to high fitness (≥ 60th percentile) was associated with twice the risk of developing hypertension.11 Similarly, another large study assessing maximal treadmill exertion in 6039 normotensive men and women with no history of cardiovascular disease found that after a median 4 years of follow‐up, participants with low levels of fitness had a 52% greater risk of developing hypertension compared to highly fit persons.20 Our study is unique in that we examined fitness in a large, diverse patient population, using a standardized clinical assessment tool, the Bruce protocol stress test. Furthermore, our patient population was at greater risk of developing cardiovascular disease, having already been referred for stress test. Not only did we find fitness to be associated with hypertension independent of traditional hypertension risk factors, but this association was preserved even after excluding participants with a resting blood pressure in the prehypertensive or hypertensive range.

Several mechanisms have been proffered to explain how increased fitness might prevent hypertension. One recent study has shown that exercise training increases endothelial production of nitric oxide synthase, decreases aortic stiffness, and increases whole‐body insulin sensitivity.6 Other studies have found that exercise training reduces circulating noradrenaline and decreases vascular resistance.23 It has also been shown that greater fitness is associated with lower body weight,24 an important risk factor for hypertension.25 Another pathway is through heart rate—fitness reduces heart rate, an important mediator of arterial stiffness.26–27 Finally, it has also recently been shown that lactate, a marker strongly associated with fitness, is a risk factor for incident hypertension.28 It is possible that rather than contribute directly to hypertension, fitness represents preexistent, oxidative capacity based on one's genetic constitution rather than physical conditioning.

Among various subgroups of patients, we found that fitness was inversely associated with incident hypertension in the old (>59 years) and young (<40 years), in men and women, and in black and white participants. While fitness has been shown to be similarly associated with incident hypertension in young people,13 men,14 and women,10 few studies have examined the association between fitness in the elderly29 or in black versus white racial groups. Also, similar to other studies, we found that obesity23 did not alter the relationship between fitness and incident hypertension. With regard to normotensive resting blood pressure, like other studies, fitness was significantly associated with incident hypertension regardless of normotensive status.19–20 However, in participants with diabetes, we found the relationship between fitness and incident hypertension was substantially attenuated, though the interaction term was not significant. This is in contrast to studies showing a strong relationship between fitness and incident hypertension in persons with diabetes.9 This may reflect the fact that the maximal level of METs achieved among participants with diabetes was lower than the METs achieved among those without diabetes. This would attenuate the relationship in participants with diabetes, since METs demonstrate the strongest inverse relationship with incident hypertension at higher levels.

This study has important public health ramifications. In 2008, hypertension was diagnosed in about 46 000 ambulatory visits in the United States, making it the most commonly diagnosed medical condition.2 Hypertension is an important risk factor for cardiovascular events.3,30 Our findings add compelling evidence in support of a role for fitness and regular exercise in the prevention of hypertension regardless of age, sex, or race. Furthermore, our study demonstrates that fitness is inversely associated with incident hypertension in persons with and without cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity or an elevated resting blood pressure, suggesting a role for fitness in at‐risk populations.

This study has a number of important limitations that warrant discussion. First, incident hypertension was based on medical records and administrative claims files, which did not include direct measurement of blood pressure. As a result, a number of persons with undiagnosed hypertension may have been misclassified as noncases, attenuating our results. Furthermore, diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of hypertension may have varied by clinic setting. Despite this, our study has the advantage of having been reviewed by clinical practitioners responsible for the medical record entry or claims data. Second, hypertensive medication use was utilized in the determination of hypertensive status. However, some medications commonly used for the treatment of hypertension have other clinical indications, which could lead to misclassification. Third, our assessment of baseline fitness was based on a single measurement. As a result, we could not evaluate changes in fitness over time. Despite this point, a number of studies suggest that physical activity behaviors only account for a fraction of fitness, while genetic composition may be a more significant determinant of fitness.31 Fourth, physical activity was not formally assessed in this study. Other studies have suggested an independent role for physical activity with regard to hypertension risk;13,27 however, self‐identified sedentary lifestyle was not associated with incident hypertension in this study. Fifth, our study population was derived from persons referred for a stress test. As a result, their baseline risk of cardiovascular disease is likely greater than the general population, which may affect the generalizability of our findings. Sixth, logistic regression was used in the prevalence analysis, which while more readily interpretable, does not approximate relative risk well because hypertension was not a rare diagnosis at baseline. Finally, residual confounding is always a limitation of observational studies. This is particularly a concern with regard to several covariates (eg, socioeconomic status [not assessed] or obesity, which was assessed via self‐report and via the medical record rather than through direct measurement).

Our study also has multiple strengths, including its large and diverse population sample, accurate and detailed medical records, variety of indications for stress testing, and rigorous direct assessment of fitness via treadmill stress testing. Furthermore, we utilized the Bruce protocol for treadmill testing, a standardized clinical measure readily interpreted in clinical settings.

Perspectives

In conclusion, greater fitness is not only associated with a lower probability of having hypertension, but moreover it is associated with a lower risk of developing hypertension in the future. These findings provide additional support for fitness in the prevention of hypertension, even in individuals at increased risk for cardiovascular disease. Future studies are necessary to delineate the specific biologic pathways by which increased fitness level decreases risk of incident hypertension.

Sources of Funding

Juraschek was supported by NIH Heart, Lung and Blood Institute T32HL007024 Cardiovascular Epidemiology Training Grant.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and participants of the FIT project for their important contributions.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, III, Mussolino ME, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Pandey DK, Paynter NP, Reeves MJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MDAmerican Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014; 129:e28-e292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2008. 2008. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/docvisit.htm. Accessed November 22, 2011.

- 3.Kannel WB, Schwartz MJ, McNamara PM. Blood pressure and risk of coronary heart disease: the Framingham study. Chest. 1969; 56:43-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klag MJ, Whelton PK, Appel LJ. Effect of age on the efficacy of blood pressure treatment strategies. Hypertension. 1990; 16:700-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Praet SFE, Jonkers RAM, Schep G, Stehouwer CDA, Kuipers H, Keizer HA, van Loon LJ. Long‐standing, insulin‐treated type 2 diabetes patients with complications respond well to short‐term resistance and interval exercise training. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008; 158:163-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cocks M, Shaw CS, Shepherd SO, Fisher JP, Ranasinghe AM, Barker TA, Tipton KD, Wagenmakers AJM. Sprint interval and endurance training are equally effective in increasing muscle microvascular density and eNOS content in sedentary males. J Physiol. 2013; 591Pt 3:641-656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meredith CN, Frontera WR, Fisher EC, Hughes VA, Herland JC, Edwards J, Evans WJ. Peripheral effects of endurance training in young and old subjects. J Appl Physiol. 1989; 66:2844-2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogunleye AA, Sandercock GR, Voss C, Eisenmann JC, Reed K. Prevalence of elevated mean arterial pressure and how fitness moderates its association with BMI in youth. Public Health Nutr. 2013; 16:2046-2054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cardoso CR, Maia MD, de Oliveira FP, Leite NC, Salles GF. High fitness is associated with a better cardiovascular risk profile in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Hypertens Res. 2011; 34:856-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barlow CE, LaMonte MJ, Fitzgerald SJ, Kampert JB, Perrin JL, Blair SN. Cardiorespiratory fitness is an independent predictor of hypertension incidence among initially normotensive healthy women. Am J Epidemiol. 2006; 163:142-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carnethon MR, Gidding SS, Nehgme R, Sidney S, Jacobs DR, Jr, Liu K. Cardiorespiratory fitness in young adulthood and the development of cardiovascular disease risk factors. JAMA. 2003; 290:3092-3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chase NL, Sui X, Lee D, Blair SN. The association of cardiorespiratory fitness and physical activity with incidence of hypertension in men. Am J Hypertens. 2009; 22:417-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carnethon MR, Evans NS, Church TS, Lewis CE, Schreiner PJ, Jacobs DR, Jr, Sternfeld B, Sidney S. Joint associations of physical activity and aerobic fitness on the development of incident hypertension: coronary artery risk development in young adults. Hypertension. 2010; 56:49-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banda JA, Clouston K, Sui X, Hooker SP, Lee C‐D, Blair SN. Protective health factors and incident hypertension in men. Am J Hypertens. 2010; 23:599-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams PT. Vigorous exercise, fitness and incident hypertension, high cholesterol, and diabetes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008; 40:998-1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawada S, Tanaka H, Funakoshi M, Shindo M, Kono S, Ishiko T. Five year prospective study on blood pressure and maximal oxygen uptake. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1993; 20:483-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gillum RF, Taylor HL, Anderson J, Blackburn H. Longitudinal study (32 years) of exercise tolerance, breathing response, blood pressure, and blood lipids in young men. Arteriosclerosis. 1981; 1:455-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Wing AL, Hyde RT, Jung DL. Physical activity and incidence of hypertension in college alumni. Am J Epidemiol. 1983; 117:245-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jae SY, Heffernan KS, Yoon ES, Park SH, Carnethon MR, Fernhall B, Choi Y‐H, Park WH. Temporal changes in cardiorespiratory fitness and the incidence of hypertension in initially normotensive subjects. Am J Hum Biol. 2012; 24:763-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blair SN, Goodyear NN, Gibbons LW, Cooper KH. Physical fitness and incidence of hypertension in healthy normotensive men and women. JAMA. 1984; 252:487-490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shook RP, Lee D, Sui X, Prasad V, Hooker SP, Church TS, Blair SN. Cardiorespiratory fitness reduces the risk of incident hypertension associated with a parental history of hypertension. Hypertension. 2012; 59:1220-1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al‐Mallah MH, Keteyian SJ, Brawner CA, Whelton S, Blaha MJ. Rationale and design of the Henry Ford exercise testing project (The FIT project). Clin Cardiol. 2014; 37:456-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fagard RH. Physical activity in the prevention and treatment of hypertension in the obese. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999; 31Suppl. 11:S624-S630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ross R, Katzmarzyk PT. Cardiorespiratory fitness is associated with diminished total and abdominal obesity independent of body mass index. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003; 27:204-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stamler R, Stamler J, Riedlinger WF, Algera G, Roberts RH. Weight and blood pressure. Findings in hypertension screening of 1 million Americans. JAMA. 1978; 240:1607-1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quan HL, Blizzard CL, Sharman JE, Magnussen CG, Dwyer T, Raitakari O, Cheung M, Venn AJ. Resting heart rate and the association of physical fitness with carotid artery stiffness. Am J Hypertens. 2014; 27:65-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boreham CA, Ferreira I, Twisk JW, Gallagher AM, Savage MJ, Murray LJ. Cardiorespiratory fitness, physical activity, and arterial stiffness: the Northern Ireland Young Hearts Project. Hypertension. 2004; 44:721-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juraschek SP, Bower JK, Selvin E, Subash Shantha GP, Hoogeveen RC, Ballantyne CM, Young JH. Plasma lactate and incident hypertension in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am J Hypertens. 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krause MP, Hallage T, Gama MPR, Miculis CP, da Matuda N, da Silva S. Association of fitness and waist circumference with hypertension in Brazilian elderly women. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2009; 93:2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Larson MG, Massaro JM, Vasan RS. Predicting the 30‐year risk of cardiovascular disease: the Framingham heart study. Circulation. 2009; 119:3078-3084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fagard RH. Physical activity, physical fitness and the incidence of hypertension. J Hypertens. 2005; 23:265-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]