Introduction

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) was identified by the Institute of Medicine as one of the top 100 priorities for comparative effectiveness research because of the large population of patients affected with significant morbidity and mortality, the multiple potential treatment options, and the high costs of care to the health care system.1 The goal of medical therapy in patients with PAD is to reduce the risk of future cardiovascular (CV) morbidity and mortality, improve walking distance and functional status in patients with intermittent claudication (IC), and reduce amputation in patients with critical limb ischemia (CLI). Secondary prevention includes the use of antiplatelet agents and the management of other risk factors, such as tobacco use, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. It is not clear which antiplatelet strategy (aspirin versus clopidogrel or monotherapy versus dual antiplatelet therapy [DAPT]) is of most benefit. Furthermore, the role of these agents in patients with asymptomatic PAD is also unclear.

We conducted a systematic review evaluating various treatment modalities for PAD.2 This article, which is derived from that review, focuses on the comparative effectiveness and safety of (1) aspirin versus placebo or no antiplatelet, (2) clopidogrel versus aspirin, (3) clopidogrel plus aspirin versus aspirin alone, and (4) other antiplatelet comparisons.

Methods

Data Sources and Searches

Searches were limited to articles published from January 1995 to August 2012. Exact search strings are listed in the full Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) report.2 We supplemented electronic searches with a manual search of references from systematic reviews and pivotal articles in the field. We also searched the gray literature of study registries and conference abstracts for relevant articles from completed studies that have not been published in a peer‐reviewed journal, including ClinicalTrials.gov, the World Health Organization's International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal, and the ProQuest COS Conference Papers Index. Scientific information packets were requested from manufacturers of medications and devices and reviewed for relevant articles.

Study Selection

Studies were limited to adult populations aged 18 years or older with lower‐extremity PAD. English‐language randomized or observational studies were included. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are in the full report.2

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Abstracted data included study design, patient characteristics overall and by study group (age, sex, and race), vascular disease risk factors (diabetes, tobacco use, chronic kidney disease, hyperlipidemia, or other comorbid diseases), and intervention‐specific factors (antiplatelet therapy, and, if applicable, type of endovascular or surgical revascularization). Outcomes captured included overall morality, CV mortality, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), nonfatal stroke, repeat revascularization, vessel patency, and composite CV events (CVEs; CV mortality, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke). Safety outcomes included adverse drug reactions and bleeding. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

We evaluated the quality of individual studies as described in the AHRQ's “Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews,”3 assigning summary ratings of good, fair, or poor.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Continuous variable outcomes were summarized as reported by the investigators. This included means, medians, standard deviations, interquartile ranges, ranges, and associated P values. Dichotomous variables were summarized by proportions and associated P values. We then determined the feasibility of completing a quantitative synthesis (ie, meta‐analysis). Feasibility depended on the volume of relevant literature, conceptual homogeneity of the studies, and completeness of the reporting of results. We considered meta‐analysis for comparisons where at least 3 studies reported the same outcome at similar follow‐up intervals. However, no meta‐analyses were performed owing to insufficient numbers of similar studies that could be combined. Thus, forest plots with the individual study results were created for a graphical display of the findings relative to each other.

Two reviewers evaluated the strength of evidence (SOE) using the 4 required domains described in the AHRQ's “Methods Guide”3: risk of bias, consistency, directness, and precision. We assigned an overall grade for the SOE as high (evidence reflects the true effect), moderate (further research may change the estimate of effect), low (further research is likely to change the estimate), or insufficient (an estimate of effect is not possible with the available data). When appropriate, we also evaluated studies for coherence, dose‐response association, residual confounding, strength of association (magnitude of effect), publication bias, and applicability.

Results

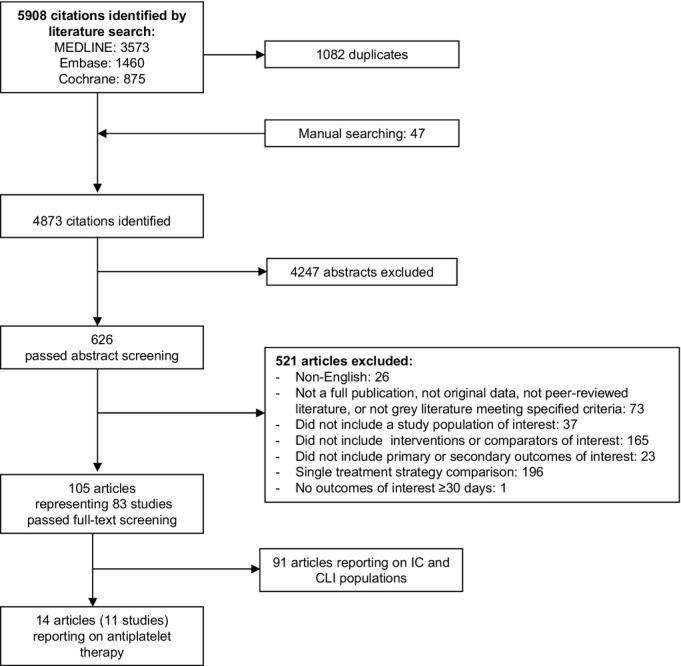

We identified 11 unique studies that evaluated the comparative effectiveness of aspirin and antiplatelet agents in 15 500 patients with PAD.4–16 Of these studies, 7 were graded good quality, 3 fair, and 1 poor. Figure 1 depicts the flow of articles through the literature search and screening process. Table 1 gives an overview of the antiplatelet comparisons, populations, designs, and primary outcomes for the studies included in the analysis. SOE (Table 2) varied by PAD population and clinical outcome for each treatment comparison.

Figure 1.

Literature flow for inclusion/exclusion of antiplatelet studies. Adapted from Jones et al.2 CLI indicates critical limb ischemia; IC, intermittent claudication.

Table 1.

Studies by Antiplatelet Comparisons

| Antiplatelet Comparison/Concomitant Therapy | Study | Population | Study Design/Quality | Primary Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin vs placebo studies | ||||

| Aspirin 100 mg daily vs placebo Standard therapy (statins, beta blockers) at discretion of clinician. |

Belch et al4 POPADAD Study |

Patients with diabetes and asymptomatic PAD | RCT/Good | CV death, nonfatal MI, stroke, or amputation for CLI |

| Aspirin 100 mg daily vs placebo Standard therapy (diuretic, beta blocker, nitrate, calcium‐channel blocker, ACE inhibitor or ARB, or statin) at discretion of clinician |

Fowkes et al5 | Asymptomatic PAD | RCT/Good | CV death, nonfatal MI, stroke, or revascularization |

| Aspirin 100 mg daily vs placebo Antioxidants (600 mg vitamin E, 250 mg vitamin C, and 20 mg beta‐carotene) daily |

Catalano et al6 CLIPS Study |

Asymptomatic PAD or IC | RCT/Fair | CV death, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke |

| Aspirin vs no aspirin No concomitant therapy specified |

Mahmood et al7 | CLI | Retrospective cohort/Poor | CV mortality, nonfatal MI, stroke, or graft patency |

| Aspirin vs active comparator studies | ||||

| Aspirin 300 mg daily vs iloprost 2 ng/kg/min for 3 days, then aspirin 300 mg daily vs no antiplatelet therapy No concomitant therapy specified |

Horrocks et al8 | IC‐CLI (after femoropopliteal PTA) | RCT/Fair | Platelet uptake, restenosis |

| Aspirin 1000 mg daily vs aspirin 100 mg daily 500 mg aspirin IV at least 1 hour before procedure, then for 2 days thereafter; 5000 IU heparin during the procedure, then 3 days thereafter |

Minar et al9 | IC‐CLI (undergoing femoropopliteal PTA) | RCT/Fair | Vessel patency |

| Clopidogrel studies | ||||

| Clopidogrel 75 mg daily vs aspirin 325 mg daily No concomitant therapy specified |

Anonymous 10 CAPRIE Study |

PAD subset of high‐risk vascular population | RCT/Good | CV mortality, nonfatal MI, or ischemic stroke |

| Clopidogrel 75 mg plus aspirin 75 to 162 mg daily vs aspirin 75 to 162 mg daily Standard therapy (diuretic, beta blocker, nitrate, calcium‐channel blocker, ACE inhibitor or ARB, or statin) at discretion of clinician |

Cacoub et al11 Bhatt et al12 Berger et al13 CHARISMA Study |

PAD subset of high‐risk vascular population | RCT/Good | Cardiovascular mortality, nonfatal MI or stroke |

| Clopidogrel 75 mg plus aspirin 75 mg daily vs aspirin 75 mg daily No concomitant therapy specified |

Cassar et al14 | IC | RCT/Good | Platelet function |

| Clopidogrel 75 mg plus aspirin 75 to 100 mg daily vs aspirin 75 to 100 mg daily High‐dose unfractionated heparin or low‐molecular‐weight heparin was used during surgery and was permitted for use for DVT prevention when indicated |

Belch et al15 CASPAR Study |

IC‐CLI (undergoing below the knee bypass) | RCT/Good | Mortality, reocclusion, revascularization, or amputation |

| Clopidogrel 75 mg plus aspirin 100 mg daily vs aspirin 500 mg daily Clopidogrel 300 mg plus ASA 500 mg 6 to 12 h before the intervention as a bolus |

Tepe et al16 MIRROR Study |

IC‐CLI | RCT/Good | Concentration of platelet uptake markers |

ARB indicates angiotensin receptor blockers; ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; CLI, critical limb ischemia; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; IC, intermittent claudication; MI, myocardial infarction; mg, milligrams; PAD, peripheral artery disease; PTA, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty; RCT, randomized, controlled trial.

Adapted from Jones et al.2

Table 2.

Summary SOE for Comparative Effectiveness and Safety of Antiplatelet Therapy for Adults With PAD

| Outcome SOE | Results or Effect Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Aspirin vs placebo in adults with asymptomatic or symptomatic PAD at 2+ years | |

| Asymptomatic population | |

| All‐cause mortality SOE=high |

2 RCTs, 3986 patients HR 0.93 (0.71 to 1.24) HR 0.95 (0.77 to 1.16) No difference |

| Nonfatal MI SOE=high |

2 RCTs, 3986 patients HR 0.98 (0.68 to 1.42) HR 0.91 (0.65 to 1.29) No difference |

| Nonfatal stroke SOE=high |

2 RCTs, 3986 patients HR 0.71 (0.44 to 1.14) HR 0.97 (0.62 to 1.53) No difference |

| CV mortality SOE=moderate |

2 RCTs, 3986 patients HR 1.23 (0.79 to 1.92) HR 0.95 (0.77 to 1.17) No difference |

| Composite vascular events SOE=high |

2 RCTs, 3986 patients HR 0.98 (0.76 to 1.26) HR 1.00 (0.85 to 1.17) No difference |

| Functional outcomes Quality of life Safety concerns (subgroups) SOE=insufficient |

0 studies |

| Modifiers of effectiveness (subgroups) SOE=insufficient |

2 RCTs, 3986 patients Inconclusive evidence owing to imprecision, with 1 study reporting similar rates of CV outcomes by age, sex, or baseline ABI and 1 study reporting similar rates of CV mortality and stroke by diabetic status |

| Safety concerns SOE=insufficient |

2 RCTs, 3986 patients Inconclusive evidence due to heterogeneous results between aspirin and placebo in regard to major hemorrhage and GI bleeding rates |

| IC population | |

| Nonfatal MI SOE=low |

1 RCT, 181 patients HR 0.18 (0.04 to 0.82) Favors aspirin |

| Nonfatal stroke SOE=insufficient |

1 RCT, 181 patients HR 0.54 (0.16 to 1.84) Inconclusive evidence owing to imprecision |

| CV mortality SOE=insufficient |

1 RCT, 181 patients HR 1.21 (0.32 to 4.55) Inconclusive evidence owing to imprecision |

| Composite vascular events SOE=low |

1 RCT, 181 patients HR 0.35 (0.15 to 0.82) Favors aspirin |

| Functional outcomes Quality of life Safety concerns (subgroups SOE=insufficient |

0 studies |

| Modifiers of effectiveness (subgroups) SOE=insufficient |

1 RCT, 216 patients Inconclusive evidence owing to imprecision, with 1 study reporting similar rates in vessel patency by sex |

| Safety concerns SOE=insufficient |

1 RCT, 181 patients Inconclusive evidence owing to imprecision, with 1 study reporting a bleeding rate of 3% in aspirin group and 0% in placebo group |

| CLI population | |

| Nonfatal MI SOE=insufficient |

1 observational study, 113 patients Inconclusive evidence owing to imprecision, with 1 study reporting MI rate of 1.2% in aspirin group and 5.9% in no‐aspirin group |

| Nonfatal stroke SOE=insufficient |

1 observational study, 113 patients Inconclusive evidence owing to imprecision, with 1 study reporting stroke rate of 2.5% in aspirin group and 8.8% in no‐aspirin group |

| CV mortality SOE=insufficient |

1 observational study, 113 patients Inconclusive evidence owing to imprecision, with 1 study reporting CV mortality rate of 33% in aspirin group and 26% in no‐aspirin group |

| Functional outcomes Quality of life Modifiers of effectiveness (subgroups) Safety concerns Safety concerns (subgroups) SOE=insufficient |

0 studies |

| Clopidogrel vs aspirin in adults with IC at 2 years (CAPRIE) | |

| Nonfatal MI SOE=moderate |

1 RCT, 6452 patients HR 0.62 (0.43 to 0.88) Favors clopidogrel |

| Nonfatal stroke SOE=low |

1 RCT, 6452 patients HR 0.95 (0.68 to 1.31) No difference |

| CV mortality SOE=moderate |

1 RCT, 6452 patients HR 0.76 (0.64 to 0.91) Favors clopidogrel |

| Composite CVEs SOE=moderate |

1 RCT, 6452 patients HR 0.78 (0.65 to 0.93) Favors clopidogrel |

| All‐cause mortality Functional outcomes Quality of life Modifiers of effectiveness (subgroups) Safety concerns Safety concerns (subgroups) SOE=insufficient |

0 studies |

| Clopidogrel/aspirin vs aspirin in adults with PAD at 2 years | |

| Symptomatic‐asymptomatic population (CHARISMA) | |

| All‐cause mortality SOE=moderate |

1 RCT, 3096 patients HR 0.89 (0.68 to 1.16) No difference |

| Nonfatal MI SOE=low |

1 RCT, 3096 patients HR 0.63 (0.42 to 0.95) Favors dual antiplatelet |

| Nonfatal stroke SOE=low |

1 RCT, 3096 patients HR 0.79 (0.51 to 1.22) No difference |

| CV mortality SOE=low |

1 RCT, 3096 patients HR 0.92 (0.66 to 1.29) No difference |

| Composite CVEs SOE=moderate |

1 RCT, 3096 patients HR 0.85 (0.66 to 1.09) No difference |

| Functional outcomes Quality of life Safety concerns (subgroups) Modifiers of effectiveness (subgroups) SOE=insufficient |

0 studies |

| Safety concerns SOE=insufficient |

1 RCT, 3096 patients Inconclusive evidence owing to low rates of severe and moderate bleeding, although minor bleeding was significantly higher with DAPT (34.4%) vs ASA (20.8%) |

| IC‐CLI population (CASPAR, MIRROR, Cassar) | |

| All‐cause mortality SOE=insufficient |

2 RCTs, 931 patients CASPAR, HR 1.44 (0.77 to 2.69) MIRROR, OR 0.33 (0.01 to 8.22) Inconclusive evidence due to imprecision |

| Nonfatal MI SOE=insufficient |

1 RCT, 851 patients CASPAR, HR 0.81 (0.32 to 2.06) Inconclusive evidence owing to imprecision |

| Nonfatal stroke SOE=low |

1 RCT, 851 patients CASPAR, HR 1.02 (0.41 to 2.55) No difference |

| CV mortality SOE=insufficient |

1 RCT, 851 patients CASPAR, HR 1.44 (0.77 to 2.69) Inconclusive evidence owing to imprecision |

| Composite CVEs SOE=low (CASPAR) SOE=insufficient (MIRROR) |

2 RCTs, 931 patients CASPAR, HR 1.09 (0.65 to 1.82), no difference MIRROR, OR 0.71 (0.28 to 1.81), inconclusive evidence owing to imprecision |

| Revacularization SOE=insufficient |

2 RCTs, 931 patients CASPAR, HR 0.89 (0.65 to 1.23) MIRROR, 5% dual therapy vs 20% aspirin, P=0.04 Inconclusive evidence owing to imprecision and study heterogeneity |

| Functional outcomes Quality of life Safety concerns (subgroups) SOE=insufficient |

0 studies |

| Modifiers of effectiveness (subgroups) SOE=insufficient |

1 RCT, 851 patients Inconclusive evidence owing to imprecision, with 1 study reporting that patients with prosthetic graft had lower CV events on DAPT |

| Safety concerns SOE=insufficient |

3 RCTs, 1034 patients Inconclusive evidence owing to inconsistent results from individual studies: CASPAR study showed statistically significant higher rates of moderate and minor bleeding with DAPT; Cassar study showed more bruising with DAPT, but no significant difference in GI bleeding or hematoma; MIRROR study showed no significant difference in bleeding |

ABI indicates ankle‐brachial index; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; CI, confidence interval; CLI, critical limb ischemia; CV, cardiovascular; CVEs, cardiovascular events; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; GI, gastrointestinal; HR, hazard ratio; IC, intermittent claudication; OR, odds ratio; RCT, randomized, controlled trial; SOE, strength of evidence.

Adapted from Jones et al.2

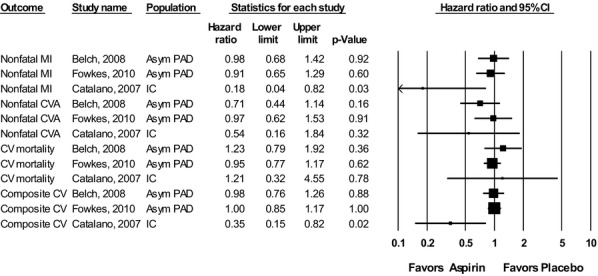

Aspirin Versus Placebo or No Antiplatelet

Figure 2 shows the hazard ratios (HRs) for various outcomes in the randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) comparing aspirin versus placebo. In the asymptomatic population at ≥2 years, aspirin compared with placebo had no statistically significant effect on CV mortality (moderate SOE), nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or composite CVEs (CV mortality, nonfatal stroke, and nonfatal MI) (all high SOE). In the IC population at ≥2 years, there was a significantly lower rate of MI and composite events in the aspirin group, compared to placebo (low SOE), but no significant difference in rates of nonfatal stroke or CV mortality (insufficient SOE). The observational study7 reported one nonfatal MI (1.2%), 2 strokes (2.5%), and 26 (33%) vascular deaths in the aspirin treatment arm and 2 nonfatal MIs (5.9%), 3 strokes (8.8%), and 9 (26%) vascular deaths in the no‐aspirin treatment arm 2 years after infrainguinal bypass for CLI (low SOE for all outcomes).

Figure 2.

Results of aspirin versus placebo trials for all outcomes. Adapted from Jones et al.2 Asym indicates asymptomatic; CI, confidence interval; CV, cardiovascular; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; IC, intermittent claudication; MI, myocardial infarction; PAD, peripheral artery disease.

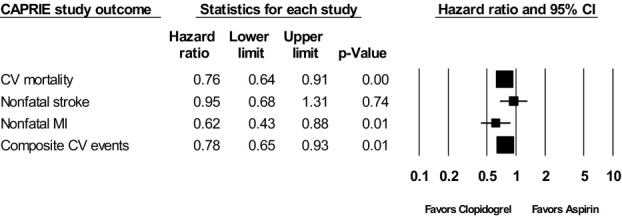

Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin

Figure 3 shows the HRs for CV mortality, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, and the composite outcome for the above for clopidogrel monotherapy versus aspirin monotherapy in the PAD subgroup of the CAPRIE study.10 There was a statistically significant benefit of clopidogrel monotherapy over aspirin monotherapy in regard to CV mortality, nonfatal MI, and composite CVEs (CV mortality, nonfatal stroke, and nonfatal MI) (moderate SOE), but no difference in the rates of nonfatal stroke (low SOE).

Figure 3.

Results of clopidogrel versus aspirin for all outcomes in the PAD Subgroup of the CAPRIE study (1996). Adapted from Jones et al.2 CI indicates confidence interval; CV, cardiovascular; MI, myocardial infarction.

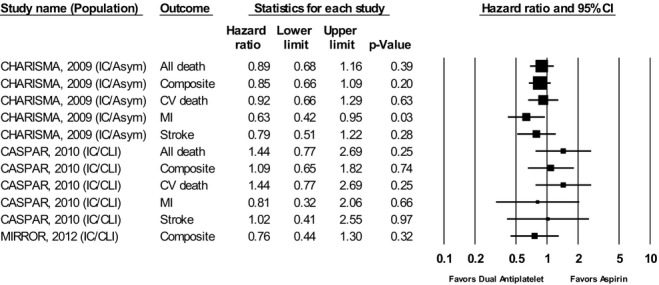

Clopidogrel Plus Aspirin (Dual Antiplatelet) Versus Aspirin Alone

Figure 4 shows the HRs for the various outcomes reported in studies examining dual antiplatelet versus aspirin. There was no significant difference in all‐cause mortality for clopidogrel plus aspirin (DAPT), compared with aspirin alone. It was not possible to calculate an HR for all‐cause mortality in the MIRROR study16 because no patients in the dual antiplatelet group died; we calculated an odds ratio (OR) of 0.33 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.01 to 8.22) showing a nonsignificant reduction in deaths in the dual antiplatelet group. There was a statistically significant decrease in nonfatal MI for DAPT, compared with aspirin alone, in the CHARISMA study11 and a nonsignificant decrease in the CASPAR study (low SOE).15 Neither study showed a significant difference of DAPT over aspirin alone for nonfatal stroke (low SOE), CV mortality (low SOE), or composite CVEs (moderate SOE). The CASPAR and MIRROR studies reported revascularization rates (insufficient SOE). The CASPAR study showed no significant difference in revascularization (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.65 to 1.23); however, the occlusion rate in the prosthetic graft subgroup was lower in patients who received DAPT at 24 months (HR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.42 to 0.63; P=0.21).15 The MIRROR study had 2 dual antiplatelet patients (5%; both clopidogrel resistant) and 8 aspirin patients (20%) who had target vessel revascularization at 6 months (P=0.04).16

Figure 4.

Results of dual antiplatelet therapy versus aspirin for all outcomes. Adapted from Jones et al.2 Asym indicates asymptomatic; CI, confidence interval; CLI, critical limb ischemia; CV, cardiovascular; IC, intermittent claudication; MI, myocardial infarction.

Other Antiplatelet Comparisons

Two fair‐quality RCTs assessed other antiplatelet comparisons in patients with IC or CLI.9–10 The study by Horrocks et al compared aspirin or iloprost versus no antiplatelet agent in patients with IC or CLI after percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) and found no significant difference in restenosis or reocclusion rates between treatment groups (aspirin 38.5% versus iloprost 0% versus placebo 21.4%).8 The study by Minar et al compared aspirin 1000 mg with aspirin 100 mg in patients with IC or CLI after femoropopliteal PTA and found no significant difference in total mortality (13.4% versus 12.3%, respectively) or vessel patency (62.5% versus 62.6%, respectively) between treatment groups.9 Neither study reported a composite outcome.

Modifiers of Effectiveness

Table 3 highlights outcomes from 4 studies (3 good quality and 1 fair) that reported variations in treatment effectiveness by subgroup.4–5,9,13 The POPADAD study compared aspirin with placebo in asymptomatic or high‐risk patients and found no significant differences in outcome based on age, sex, or ankle‐brachial index (ABI).4 Another study by Fowkes et al, also comparing aspirin with placebo in asymptomatic or high‐risk patients analyzed results by age, sex, and ABI and found no significant variation in outcomes.5 The study by Minar et al,9 which compared high‐ with low‐dose aspirin, also analyzed results by sex and found similar outcomes in men and women. One study by Belch et al showed a benefit of clopidogrel plus aspirin for reducing composite vascular events in patients with a prosthetic bypass graft, compared to those with a venous bypass graft.15 We found no studies reporting subgroup results by race or risk factors (eg, tobacco use or presence of hyperlipidemia). Given the heterogeneity of the subgroups, interventions, and clinical outcomes, the SOE for modifiers of effectiveness was insufficient.

Table 3.

Studies Reporting Subgroup Results of Antiplatelet Therapy (Modifiers of Effectiveness)

| Study Population | Study Type Total N Comparison Quality | Subgroup | Results Reported by Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belch et al4 POPADAD Study Patients with diabetes mellitus and asymptomatic PAD |

RCT Total N: 636 ASA vs placebo Good |

Diabetes | CV mortality: 21 ASA, 14 placebo Stroke: 0 ASA, 5 placebo |

| Fowkes et al5 Patients with asymptomatic PAD and no previous CVD |

RCT Total N: 3350 ASA vs placebo Good |

Age <62 y vs ≥62 y |

Composite CVEs: <62: HR 0.85 (0.65 to 1.20) ≥62: HR 1.13 (0.97 to 1.47) |

| Sex | Composite CVEs: Men: HR 1.15 (0.86 to 1.54) Women: HR 0.92 (0.68 to 1.23) |

||

| ABI ≤0.95, ≤0.90, ≤0.85, ≤0.80 |

Composite CVEs: ≤0.95: HR 1.03 (0.84 to 1.27) ≤0.90: HR 1.02 (0.80 to 1.29) ≤0.85: HR 0.99 (0.73 to 1.35) ≤0.80: HR 1.06 (0.73 to 1.54) |

||

| Belch et al15 CASPAR Study Patients with IC or CLI |

RCT Total N: 851 Clopidogrel/ASA vs ASA Good |

Type of bypass graft Venous vs .prosthetic |

Composite CVEs: Venous: HR 1.25 (0.94 to 1.67) Prosthetic: HR 0.65 (0.45 to 0.95) Significant reduction in prosthetic graft patients receiving DAPT, but not in venous graft patients |

| Minar et al9 Patients with IC or CLI |

RCT Total N: 216 ASA 1000 mg vs ASA 100 mg Fair |

Sex | Vessel patency: Aspirin dosage had no influence on cumulative patency in either sex. |

ABI indicates ankle‐brachial index; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; CLI, critical limb ischemia; CV, cardiovascular; CVD, cardiovascular disease; CVE, cardiovascular event; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; HR, hazard ratio; IC, intermittent claudication; MI, myocardial infarction; mg, milligrams; N, number of patients; PAD, peripheral artery disease; PTA, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty; RCT, randomized, controlled trial.

Adapted from Jones et al.2

Safety Concerns

Table 4 shows the 4 studies (6 good quality and 1 fair) that reported safety concerns associated with each treatment strategy.4–6,11,14–16 All 7 studies reported bleeding, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, or anemia as a harm. A quantitative analysis of bleeding rates was not possible owing to the low number of studies by treatment comparison, variation in the bleeding definition, and differences in measurement time points. In 2 aspirin versus placebo studies, the rates of major hemorrhage or bleeding were slightly higher in the aspirin groups.4–5 A third study showed lower rates of GI bleeding in the aspirin group.5 In the dual antiplatelet groups, bleeding rates ranged from 2% to 3% (with 1 study showing a rate of 28% in the immediate postoperative period), compared to bleeding rates ranging from 0% to 6% in the placebo groups. There was no significant difference in bleeding except in the immediate postoperative period.11,14–16 Two studies reported the adverse side effect of a rash, which was higher in patients receiving aspirin compared to placebo,4 and similar in patients receiving DAPT or aspirin.14 None of the studies reported on whether any harms varied by subgroup (age, sex, race, risk factors, comorbidities, or anatomic location of disease). Therefore, the SOE for safety concerns is insufficient.

Table 4.

Studies Reporting Safety Concerns

| Study Population | Study Type Total N Comparison Quality | Harm(s) (Length of Follow‐up) | Results Reported by Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belch et al4 POPADAD study Patients with diabetes mellitus and asymptomatic PAD |

RCT Total N: 636 ASA vs placebo Good |

GI bleeding, GI symptoms, arrhythmia, rash (6.7 y) |

GI bleeding: ASA 13 (4%), placebo 18 (6%) GI symptoms: ASA 40 (13%), placebo 58 (18%) Arrhythmia: ASA 27 (9%), placebo 25 (8%) Rash: ASA 38 (12%), placebo 30 (9%) |

| Fowkes et al5 Patients with asymptomatic PAD and no previous CVD |

RCT Total N: 3350 ASA vs placebo Good |

Major hemorrhage (hemorrhagic stroke, subarachnoid/subdural hemorrhage, GI bleeding), GI ulcer, retinal hemorrhage, severe anemia (10 y) |

Major hemorrhage: ASA 2.0%, placebo 1.2% GI ulcer: ASA 0.8%, placebo 0.5% Retinal hemorrhage: ASA 0.1%, placebo 0.2% Severe anemia: ASA 25, placebo 16 |

| Catalano et al6 CLIPS study Patients with IC |

RCT Total N: 181 ASA vs placebo Fair |

Bleeding (2 y) |

ASA 3% (1 melena, 2 retinal hemorrhage, 1 epistaxis), placebo 0% |

| Cacoub et al11 CHARISMA study PAD subgroup (92% CI, 8% asymptomatic) |

RCT Total N: 3096 Clopidogrel/ASA vs ASA Good |

Bleeding (based on GUSTO criteria) (28 m) |

Severe bleeding Clopidogrel/ASA 1.7%, ASA 1.7%, P=0.90 Moderate bleeding: Clopidogrel/ASA 2.5%, ASA 1.9%, P=0.26 Minor bleeding: Clopidogrel/ASA 34.4%, ASA 20.8%, P<0.001 |

| Cassar et al14 Patients with IC status post‐PTA |

RCT Total N: 132 Clopidogrel/ASA vs. ASA Good |

GI bleeding, rash, hematoma, bruising (30 days) |

GI bleeding: Clopidogrel/ASA 1, ASA 0 Rash: Clopidogrel/ASA 2, ASA 2 Hematoma: Clopidogrel/ASA 2 peripheral and 1 retroperitoneal ASA 2 Bruising: Clopidogrel/ASA 25, ASA 16 |

| Belch et al15 CASPAR study Patients with IC or CLI status postunilateral bypass graft |

RCT Total N: 851 Clopidogrel/ASA vs ASA Good |

Bleeding (based on GUSTO criteria) (2 y) |

All Bleeding: Clopidogrel 71 (16.7%), placebo 30 (7.1%), P=0.001 Severe bleeding: Clopidogrel 9 (2.1%); placebo 5 (1.2%), P=NS Moderate bleeding: clopidogrel 16 (3.8%); placebo 4 (0.9%), P=0.007 Mild bleeding: Clopidogrel 46 (10.8%); placebo 21 (5%), P=0.002 |

| Tepe et al16 MIRROR study Patients with IC or CLI status post‐PTA |

RCT Total N: 80 Clopidogrel/ASA vs ASA Good |

Bleeding (6 m) |

Bleeding: Clopidogrel 1 GI ulcer bleed (2.5%), placebo 2 minor access site bleeding (5%), P=0.559 |

ASA indicates acetylsalicylic acid; CI, confidence interval; CLI, critical limb ischemia; CVD, cardiovascular disease; GI, gastrointestinal; HR, hazard ratio; IC, intermittent claudication; m, month/months; N, number of patients; NS, not significant; PTA, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty; RCT, randomized, controlled trial; y, year/year.

Adapted from Jones et al.2

Table 5.

Overall Summary of Findings on the Effectiveness of Antiplatelet Therapy for PAD

| Eleven unique studies (10 RCTs, 1 observational) evaluated the comparative effectiveness of aspirin and antiplatelet agents in 15 150 patients with PAD. Asymptomatic population

|

CLI critical limb ischemia; CV, cardiovascular; IC, intermittent claudication; MI, myocardial infarction; PAD, peripheral artery disease; RCT, randomized, controlled trial; SOE, strength of evidence.

Adapted from Jones et al.2

Discussion

The 3 major findings of this review are: (1) Aspirin has no benefit in the asymptomatic PAD patient; (2) clopidogrel monotherapy is more beneficial than aspirin in the IC patient; and (3) DAPT is not significantly better than aspirin at reducing CVEs in patients with IC or CLI. The unique features of this comparative effectiveness review include an assessment of studies published since 1995 to increase applicability to clinical practice, presentation of results by PAD clinical population (asymptomatic, IC, or CLI), and grading of the SOE using AHRQ methodology. We used 1995 as the start date for the literature search to improve the applicability of the findings to current clinical practice in an era when secondary prevention of CVEs includes smoking cessation counseling and treatment of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia. Current guideline recommendations include reaching specific blood pressure, hemoglobin A1c, and lipid‐lowering goals as well as providing access to nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation.17 By removing studies preceding 1995, we acknowledge that earlier comparative studies of aspirin and dipyridamole were not included in this review. Including older studies with outdated background medical therapy for CV risk (CVR) factors may have biased the results to favor active treatment over suboptimal usual‐care treatment. We also appreciate that, even in the post‐1995 era, there have been differences in the recommendations for, and adherence to, treatment of other CVR factors, which may differentially affect outcomes in older versus more recent studies within this time period.

Data available for antiplatelet agents in PAD treatment fell into 2 categories:subgroup analysis of PAD patients in large antiplatelet RCTs and patients who recently had an endovascular intervention or bypass surgery in smaller antiplatelet RCTs. There are no trials that specifically evaluate the role of antiplatelet agents in a population of patients representing the full spectrum of PAD (asymptomatic, IC, and CLI).

Our findings on the effectiveness of aspirin are similar to a meta‐analysis of 18 studies published in 2009 by Berger et al.18 In the subset treated with aspirin alone compared to placebo, they found a nonsignificant reduction in CVEs (defined as nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, and CV mortality; relative risk [RR], 0.75; 95% CI, 0.48 to 1.18), a significant reduction in nonfatal stroke (RR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.42 to 0.99), and no statistically significant reductions in nonfatal MI, CV mortality, or major bleeding. In the Berger et al meta‐analysis, 12 of the 18 studies were in patients who were treated before or after a revascularization procedure. We felt this represented a population with evidence of clinical disease and possible interaction with revascularization therapies. The study by Fowkes et al5 was published after that meta‐analysis and is the largest study of asymptomatic patients with PAD who have no established CV disease. Therefore, our review of 3 aspirin versus placebo studies4–6 contains the most recent evidence for the effectiveness of aspirin in the current era. Additionally, the current meta‐analysis includes more asymptomatic patients treated with aspirin for PAD and may represent a treatment effect by symptom status. The lack of clinical effectiveness of 100 mg daily of aspirin in addition to more‐aggressive management of CVR factors is of clinical note and consistent with the meta‐analysis by Berger et al, when viewed with regard to background therapy. Our findings support current guidelines that recommend aspirin in symptomatic PAD patients to reduce the risk of MI, stroke, or vascular death, but do not support the recommendations for antiplatelet therapy to reduce the risk of these outcomes in asymptomatic PAD patients.17

The findings for clopidogrel monotherapy or DAPT were evaluated within subgroups of large, randomized trials. Our finding that clopidogrel monotherapy is superior or equivalent to aspirin monotherapy in reducing adverse CV outcomes from 1 good‐quality RCT in a PAD subgroup population represents current clinical practice and helps reinforce the current guideline recommendations for patients with PAD.10,17 The role for DAPT compared with aspirin monotherapy is less certain. From the PAD subgroup analysis of 1 large clinical trial11–12 and a smaller study on a postrevascularization population,15 the combination of clopidogrel plus aspirin as DAPT did not show a significant benefit in reducing stroke events or CV mortality in IC patients. In patients with symptomatic or asymptomatic PAD (92% IC and 8% asymptomatic), the PAD subgroup analysis of the CHARISMA study did, however, show a statistically significant benefit favoring dual therapy (clopidogrel plus aspirin) compared with aspirin for reducing nonfatal MI, but showed no difference between aspirin and dual therapy for other outcomes.11 In the only other systematic review of antiplatelet agents for IC, by the Cochrane group,19 the report included results of the CAPRIE study, but did not contain results of the CHARISMA or CASPAR studies. That review also included other antiplatelet agents, such as indobufen, picotamide, ticlopidine, and triflusal, which are not prescribed in the United States. Recently, several new antiplatelet agents have been introduced for use in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD). Effectiveness in patients with PAD is not known for most of these new agents; however, a recent study evaluating vorapaxar, a protease‐activated receptor‐1, did study the effectiveness and safety of vorapaxar or placebo, in addition to standard therapy (88% of patients were on aspirin and 28% of patients were on aspirin plus another P2Y12 inhibitor). This study showed that vorapaxar did not reduce the risk of CV death, MI, or stroke in patients with PAD, compared to placebo, but did significantly reduce acute limb ischemia and peripheral revascularization events. The study also showed that vorapaxar was associated with an increased risk of bleeding.20

The primary limitation of the available evidence was the low number of studies that compare the effectiveness of aspirin, clopidogrel, and new antiplatelet agents. A single study has compared clopidogrel with aspirin, and 2 studies have compared clopidogrel plus aspirin to aspirin alone. More studies on asymptomatic or symptomatic patients with PAD are needed to firmly conclude whether antiplatelet monotherapy or dual antiplatelet therapy is warranted in this high‐risk CV population. In addition, most of the studies were also subgroup analyses of larger antiplatelet trials that used PAD as an inclusion criteria, but randomization was not stratified by PAD. Furthermore, not all studies reported interaction analyses, thus limiting the interpretation of the results for the PAD subgroups. Finally, most new antiplatelet agents that are commercially available have not been studied in a PAD population. Given a general paucity of high‐quality studies in patients with PAD, it is encouraging that recent, large RCTs have begun to focus enrollment on a pure PAD population, rather than on a mix of high‐risk patients (CAD, cerebrovascular disease, and PAD).

Conclusions

Our findings favor clopidogrel as the monotherapy antiplatelet agent for patients with PAD, although this is based on a subgroup analysis of 1 large RCT and, with the introduction of the generic drug into clinical practice, may have important implications for health plans and medical systems. For studies aimed at improving the outcomes of patients with PAD, clopidogrel monotherapy seems justified as the current standard of care. More data are needed to understand standard of care for postrevascularization patients.

Sources of Funding

This project was funded under Contract No. 290‐2007‐10066‐I from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Disclosures

Dr Patel reports research grants to the DCRI from AstraZeneca, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, Maquet, Johnson & Johnson, and Genzyme and consultant fees/honoraria from Bayer Healthcare, Ortho McNeil Jansen, theheart.org, Ikaria, and Duke CME. Dr Jones reports research grants to the DCRI from the American Heart Association, AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, and Bristol‐Myers Squibb. All other coauthors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Megan von Isenburg, MSLS, for help with the literature search and retrieval; Rachael Posey, MSLS, and Megan Chobot, MSLS, for project coordination; and Liz Wing, MA, for editorial assistance.

References

- 1.IOM (Institute of Medicine). Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research. 2009Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2009/ComparativeEffectivenessResearchPriorities.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones WS, Schmit KM, Vemulapalli S, Subherwal S, Patel MR, Hasselblad V, Heidenfelder BL, Chobot MM, Posey R, Wing L, Sanders GD, Dolor RJ. Treatment Strategies for Patients With Peripheral Artery Disease Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 118. (Prepared by the Duke Evidencex2010based Practice Center under Contract No. 290x20102007x201010066x2010I.) AHRQ Publication No. 3x2010EHC089x2010EF. 2013. Available at: www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/reports/final.cfm. Accessed November 26, 2012. [PubMed]

- 3.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Available at: www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/index.cfm/search-for-guides-reviews-and-reports/?pageaction=displayproduct&productid=318. Accessed March 16, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belch J, MacCuish A, Campbell I, Cobbe S, Taylor R, Prescott R, Lee R, Bancroft J, MacEwan S, Shepherd J, Macfarlane P, Morris A, Jung R, Kelly C, Connacher A, Peden N, Jamieson A, Matthews D, Leese G, McKnight J, O'Brien I, Semple C, Petrie J, Gordon D, Pringle S, MacWalter R. The prevention of progression of arterial disease and diabetes (POPADAD) trial: factorial randomised placebo controlled trial of aspirin and antioxidants in patients with diabetes and asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease. BMJ. 2008; 337:a1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fowkes FG, Price JF, Stewart MC, Butcher I, Leng GC, Pell AC, Sandercock PA, Fox KA, Lowe GD, Murray GD. Aspirin for prevention of cardiovascular events in a general population screened for a low ankle brachial index: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010; 303:841-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catalano M, Born G, Peto R. Prevention of serious vascular events by aspirin amongst patients with peripheral arterial disease: randomized, double‐blind trial. J Intern Med. 2007; 261:276-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahmood A, Sintler M, Edwards AT, Smith SR, Simms MH, Vohra RK. The efficacy of aspirin in patients undergoing infra‐inguinal bypass and identification of high risk patients. Int Angiol. 2003; 22:302-307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horrocks M, Horrocks EH, Murphy P, Lane IF, Ruttley MS, Fligelstone LJ, Watson HR. The effects of platelet inhibitors on platelet uptake and restenosis after femoral angioplasty. Int Angiol. 1997; 16(2):101-106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minar E, Ahmadi A, Koppensteiner R, Maca T, Stumpflen A, Ugurluoglu A, Ehringer H. Comparison of effects of high‐dose and low‐dose aspirin on restenosis after femoropopliteal percutaneous transluminal angioplasty. Circulation. 1995; 91:2167-2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anonymous. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). Lancet. 1996; 348:1329-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cacoub PP, Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Topol EJ, Creager MA. Patients with peripheral arterial disease in the CHARISMA trial. Eur Heart J. 2009; 30:192-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatt DL, Flather MD, Hacke W, Berger PB, Black HR, Boden WE, Cacoub P, Cohen EA, Creager MA, Easton JD, Hamm CW, Hankey GJ, Johnston SC, Mak KH, Mas JL, Montalescot G, Pearson TA, Steg PG, Steinhubl SR, Weber MA, Fabry‐Ribaudo L, Hu T, Topol EJ, Fox KA. Patients with prior myocardial infarction, stroke, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease in the CHARISMA trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 49:1982-1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berger PB, Bhatt DL, Fuster V, Steg PG, Fox KA, Shao M, Brennan DM, Hacke W, Montalescot G, Steinhubl SR, Topol EJ. Bleeding complications with dual antiplatelet therapy among patients with stable vascular disease or risk factors for vascular disease: results from the Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance (CHARISMA) trial. Circulation. 2010; 121:2575-2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cassar K, Ford I, Greaves M, Bachoo P, Brittenden J. Randomized clinical trial of the antiplatelet effects of aspirin‐clopidogrel combination versus aspirin alone after lower limb angioplasty. Br J Surg. 2005; 92:159-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belch JJ, Dormandy J, Biasi GM, Cairols M, Diehm C, Eikelboom B, Golledge J, Jawien A, Lepantalo M, Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Becquemin JP, Bergqvist D, Clement D, Baumgartner I, Minar E, Stonebridge P, Vermassen F, Matyas L, Leizorovicz A. Results of the randomized, placebo‐controlled clopidogrel and acetylsalicylic acid in bypass surgery for peripheral arterial disease (CASPAR) trial. J Vasc Surg. 2010; 52:825-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tepe G, Bantleon R, Brechtel K, Schmehl J, Zeller T, Claussen CD, Strobl FF. Management of peripheral arterial interventions with mono or dual antiplatelet therapy‐the MIRROR study: a randomised and double‐blinded clinical trial. Eur Radiol. 2012; 22:1998-2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, Bakal CW, Creager MA, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Murphy WR, Olin JW, Puschett JB, Rosenfield KA, Sacks D, Stanley JC, Taylor LM, Jr, White CJ, White J, White RA, Antman EM, Smith SC, Jr, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Faxon DP, Fuster V, Gibbons RJ, Hunt SA, Jacobs AK, Nishimura R, Ornato JP, Page RL, Riegel B. ACC/AHA 2005 Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease): endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter‐Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. Circulation. 2006; 113:e463-e654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berger JS, Krantz MJ, Kittelson JM, Hiatt WR. Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with peripheral artery disease: a meta‐analysis of randomized trials. JAMA. 2009; 301:1909-1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong PF, Chong LY, Mikhailidis DP, Robless P, Stansby G. Antiplatelet agents for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011; 11(11):CD00127210.1002/14651858.CD001272.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonaca MP, Scirica BM, Creager MA, Olin J, Bounameaux H, Dellborg M, Lamp JM, Murphy SA, Braunwald E, Morrow DA. Vorapaxar in patients with peripheral artery disease: results from TRA2 P‐TIMI 50. Circulation. 2013; 127:1522-1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]