Abstract

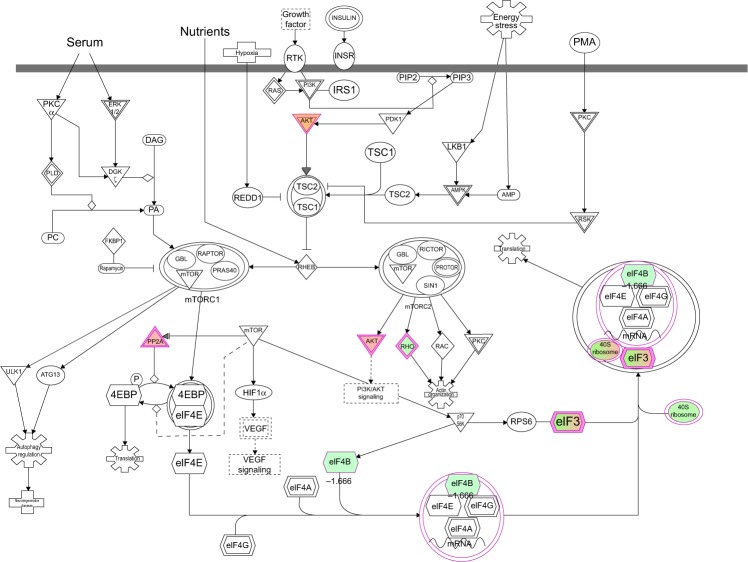

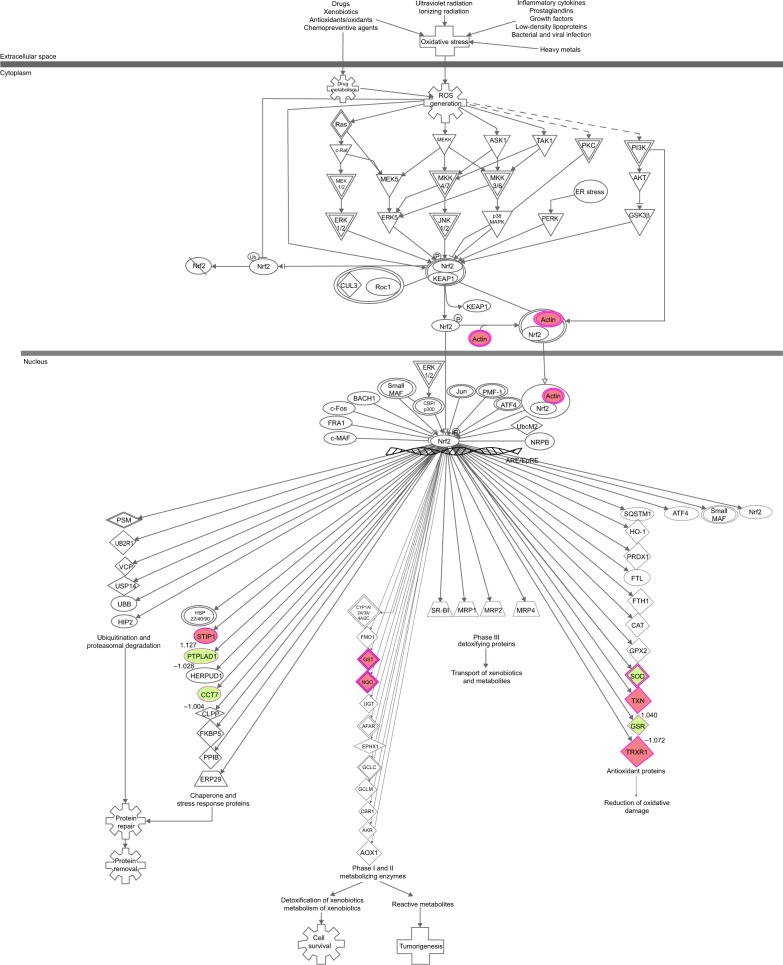

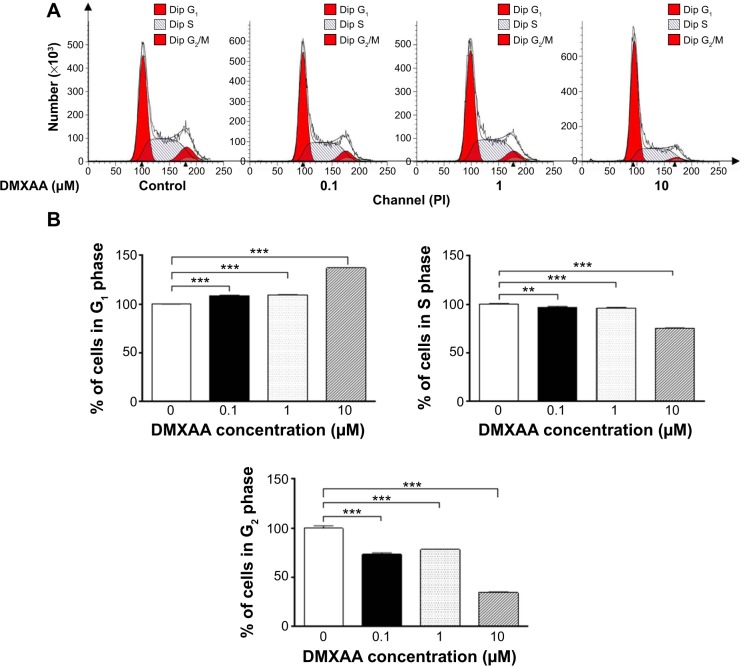

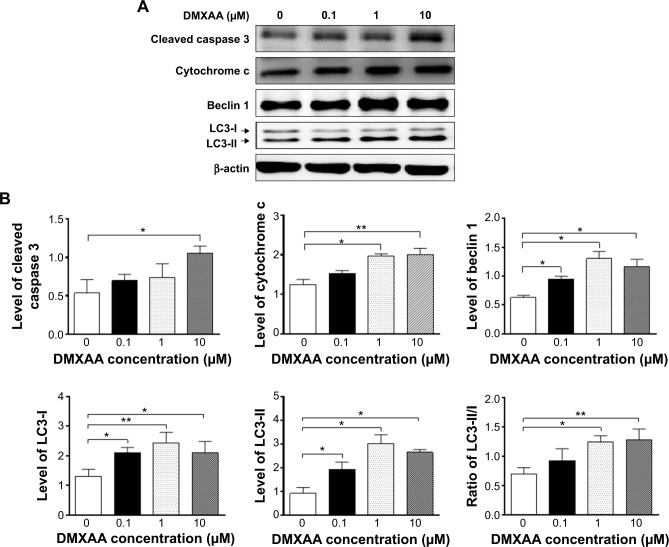

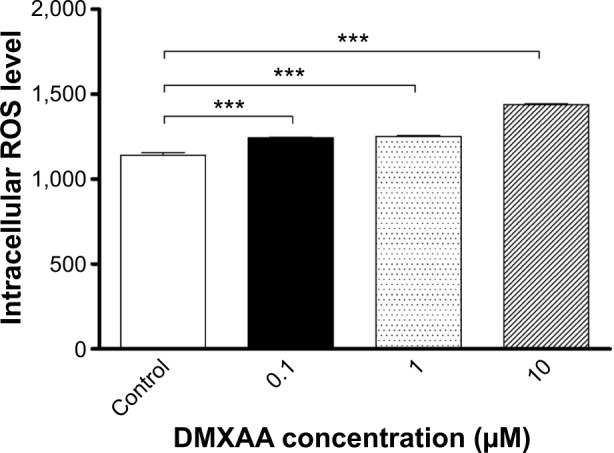

5,6-Dimethylxanthenone 4-acetic acid (DMXAA), also known as ASA404 and vadimezan, is a potent tumor blood vessel-disrupting agent and cytokine inducer used alone or in combination with other cytotoxic agents for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and other cancers. However, the latest Phase III clinical trial has shown frustrating outcomes in the treatment of NSCLC, since the therapeutic targets and underlying mechanism for the anticancer effect of DMXAA are not yet fully understood. This study aimed to examine the proteomic response to DMXAA and unveil the global molecular targets and possible mechanisms for the anticancer effect of DMXAA in NSCLC A549 cells using a stable-isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) approach. The proteomic data showed that treatment with DMXAA modulated the expression of 588 protein molecules in A549 cells, with 281 protein molecules being up regulated and 306 protein molecules being downregulated. Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) identified 256 signaling pathways and 184 cellular functional proteins that were regulated by DMXAA in A549 cells. These targeted molecules and signaling pathways were mostly involved in cell proliferation and survival, redox homeostasis, sugar, amino acid and nucleic acid metabolism, cell migration, and invasion and programed cell death. Subsequently, the effects of DMXAA on cell cycle distribution, apoptosis, autophagy, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation were experimentally verified. Flow cytometric analysis showed that DMXAA significantly induced G1 phase arrest in A549 cells. Western blotting assays demonstrated that DMXAA induced apoptosis via a mitochondria-dependent pathway and promoted autophagy, as indicated by the increased level of cytosolic cytochrome c, activation of caspase 3, and enhanced expression of beclin 1 and microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3-II) in A549 cells. Moreover, DMXAA significantly promoted intracellular ROS generation in A549 cells. Collectively, this SILAC study quantitatively evaluates the proteomic response to treatment with DMXAA that helps to globally identify the potential molecular targets and elucidate the underlying mechanism of DMXAA in the treatment of NSCLC.

Keywords: DMXAA, non-small cell lung cancer, cell cycle, apoptosis, autophagy, SILAC

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related death in humans worldwide.1,2 There were about 1.8 million new cases diagnosed with lung cancer in 2012, accounting for 12.9% of the total cases of cancer.1,2 Small-cell lung cancer and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) are the two major types of lung cancer. NSCLC is the most common type, accounting for 70%–85% of all cases of lung cancer. In the USA, there were 207,339 new cases of lung cancer and 156,953 deaths resulting from lung cancer in 2011,3 and it is estimated that there were 224,210 new cases of lung cancer and 159,260 deaths due to lung cancer in 2014.4 In the People’s Republic of China, lung cancer is the most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related death, with a skyrocketing increase in incidence and mortality rates.2,5 In 2009, the incidence rate for lung cancer was about 53.57/100,000, accounting for 18.74% of overall new cases of cancer; the mortality rate for lung cancer was about 45.57/100,000, accounting for 25.24% of cancer-related deaths.2,5 Current therapies for lung cancer include surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy, which are used alone or in combination. However, the therapeutic outcome for lung cancer is often disappointing, in particular for advanced NSCLC,6,7 due to the poor response to current therapeutics, drug resistance, and severe side effects, which highlights an urgent need for discovery of efficacious and safe new agents for the treatment of NSCLC.

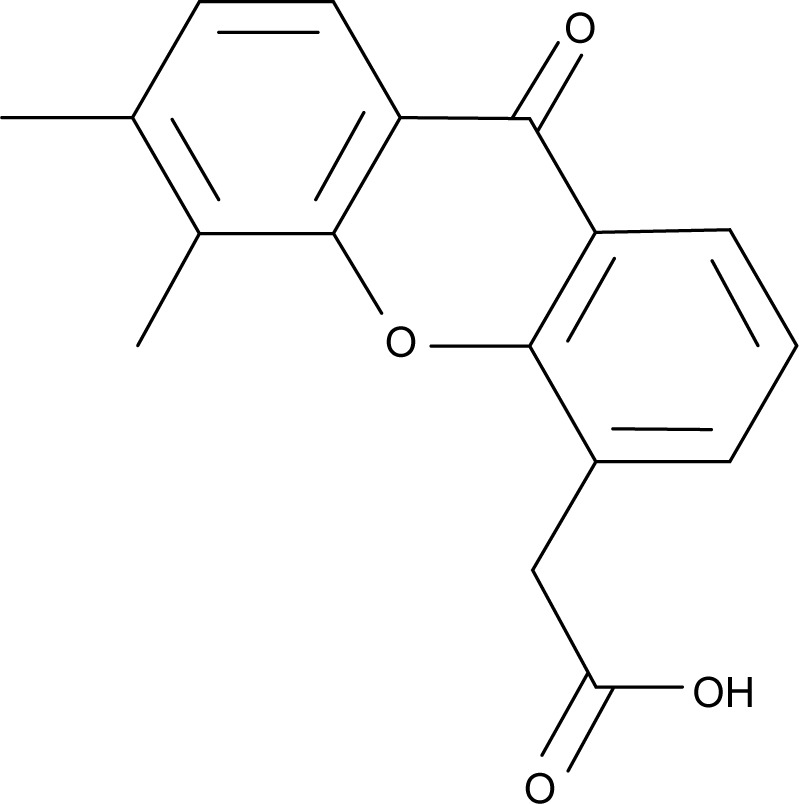

5,6-Dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA, Figure 1), also known as vadimezan and ASA404, is a vascular-disrupting agent that reduces the blood supply to tumoral tissue, resulting in tumor regression.8,9 However, the molecular targets and exact mechanisms of action of DMXAA are elusive so far. DMXAA shows inhibitory effects against several protein kinases, with the most potent effects being on the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase family.10,11 DMXAA is a potent inducer of tumor necrosis factor-α and activates host immune effectors that assist in killing cancer cells.10 DMXAA induces rapid vascular collapse and subsequent tumor hemorrhagic necrosis via induction of apoptosis in tumor vascular endothelial cells and indirect vascular effects induced by various cytokines, in particular, tumor necrosis factor-α, serotonin, and nitric oxide.10 The pharmacokinetics of DMXAA has also be investigated. In cancer patients, DMXAA concentration-time profiles are well described by a three-compartment model with saturable elimination.12 Body surface area and sex are significant covariates on the volume of distribution of the central compartment and the maximum elimination rate, respectively.12 DMXAA is extensively metabolized in human liver microsomes and cancer patients. There are two major metabolites of DMXAA, ie, DMXAA acyl glucuronide and 6-hydroxymethyl-5-methylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (6-OH-MXAA). Cytochrome P450 1A2 is responsible for the conversion of DMXAA to 6-OH-MXAA, with an apparent Km of 6.2 μM and a Vmax of 0.014 nmol/minute/mg.13 DMXAA is also extensively metabolized by uridine 5′-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase 1A2 (UGT1A2) and UGT2B7, with a greater contribution from UGT2B7.14 DMXAA has been tested mainly in the treatment of NSCLC, and also in prostate cancer and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative breast cancer.15–20 In these clinical studies, DMXAA is used alone and more often in combination with other cytotoxic drugs. A Phase II clinical trial showed that DMXAA in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel had a potent anticancer effect in NSCLC patients.15 This triple combination therapy prolonged the survival of about 5 months when compared with the monotherapy.15 However, the Phase III clinical trial conducted by Lara et al showed that the triple chemotherapy of DMXAA with carboplatin and paclitaxel failed to improve the efficacy of the monothera-py.16 This may be due to the complexity of the mechanisms of action of DMXAA. DMXAA has been shown to target the stimulator of interferon gene (STING) pathway and this effect is only observed in mice but not in humans.21–23 However, this cannot provide a convincing explanation for the failure of DMXAA in the Phase III trial in NSCLC patients. Therefore, it is of great importance to globally understand and uncover the molecular targets and related signaling pathways involved in the anticancer effect of DMXAA and DMXAA-based combination therapies.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of 5,6-dimethylxanthenone 4-acetic acid (DMXAA).

So far, there are many studies on the mechanisms of action of DMXAA in the treatment of NSCLC, showing that DMXAA can activate STING-dependent innate immune pathways and mitogen-activated protein kinases and inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.11,21–23 However, there is a lack of evidence to depict the global molecular targets and related signaling pathways for the NSCLC cell killing effects of DMXAA, such as cell proliferation, programmed cell death, and cell migration and invasion. Notably, targeting cell cycle progression, apoptosis, autophagy, and epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) has been proposed for treatment of NSCLC.24 Therefore, an approach that can evaluate cellular proteomic responses to the DMXAA is important for the optimal treatment of NSCLC. Stable-isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) is a practical and powerful approach to uncovering the global proteomic response to drug treatment and other interventions.25 In particular, it can be used to systemically and quantitatively assess the target network of drugs, to evaluate drug toxicity, and to identify new biomarkers for the diagnosis and treatment of important diseases, including NSCLC.25–27 In this regard, we investigated the molecular targets of DMXAA in A549 cells using a combination of proteomic and functional approaches, with a focus on cell cycle distribution, apoptosis, autophagy, and redox homeostasis.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

DMXAA (purity ≥ 98%), 13C6-L-lysine, L-lysine, 13C 156 N4-L-arginine, L-arginine, RNase A, propidium iodide, Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), dialyzed FBS, and Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 medium for SILAC were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St Louis, MO, USA). The 5-(and 6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2DCFDA) was sourced from Invitrogen Inc. (Carlsbad, CA, USA). A FASP™ protein digestion kit was purchased from Protein Discovery Inc. (Knoxville, TN, USA). RPMI-1640 medium for general cultural use was obtained from Corning Cellgro Inc. (Herndon, VA, USA). The polyvinylidene difluoride membrane was purchased from EMD Millipore Inc. (Bedford, MA, USA). Proteomic quantitation kits for acidification, desalting, and digestion, ionic detergent compatibility reagent, a Pierce bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit, and Western blotting substrate were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (Waltham, MA, USA). Primary antibodies against human cytochrome c, cleaved caspase 3, microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3-I (LC3-I), LC3-II, and beclin 1 were all purchased from Cell Signaling Technology Inc. (Beverly, MA, USA). The antibody against human β-actin was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Dallas, TX, USA).

Cell line and cell culture

The A549 NSCLC cell line was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS. The cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2/95% air humidified incubator. DMXAA was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at a stock concentration of 20 mM and stored at −20°C. It was freshly diluted to predetermined concentrations with culture medium. The final concentration of dimethyl sulfoxide was 0.05% (v/v). The control cells received the vehicle only.

Quantitative proteomic study using SILAC

Quantitative proteomic experiments were performed using a SILAC-based approach as described previously.25,26,28 Briefly, A549 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (for SILAC) with (heavy) or without (light) stable isotope-labeled amino acids (13C6 L-lysine and 13C6 15N4 L-arginine) and 10% dialyzed FBS. A549 cells cultured in heavy medium were treated with 10 μM DMXAA for 24 hours after six cell doubling times. After treatment with DMXAA, A549 cell samples were harvested and lysed with hot lysis buffer (100 mM Tris base, 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], and 100 mM dithiothreitol). The cell lysate was denatured at 95°C for 5 minutes and then sonicated for 3 seconds with six pulses. The samples were then centrifuged at 15,000× g for 20 minutes at room temperature and the supernatant was collected. The protein concentration was determined using ionic detergent compatibility reagent. Subsequently, equal amounts of heavy and light protein samples were combined to reach a total volume of 30–60 μL containing 300–600 μg protein. The combined protein sample was digested using an filter-aided sample prep (FASP™) protein digestion kit. After digestion, the resulting sample was acidified to a pH of 3 and desalted using a C18 solid-phase extraction column. The samples were then concentrated using a vacuum concentrator at 45°C for 120 minutes, and the peptide mixtures (5 μL) were subjected to the hybrid linear ion trap (LTQ Orbitrap XL™, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry was performed using a 10 cm long, 75 μm (inner diameter) reversed-phase column packed with 5 μm diameter C18 material having a pore size of 300 Å (New Objective Inc., Woburn, MA, USA) with a gradient mobile phase of 2%–40% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid at 200 μL per minute for 125 minutes. The Orbitrap full mass spectrometry scanning was performed at a mass (m/z) resolving power of 60,000, with positive polarity in profile mode (M + H+). The peptide SILAC ratio was calculated using MaxQuant version 1.2.0.13. The SILAC ratio was determined by averaging all peptide SILAC ratios from peptides identified of the same protein. The proteins were identified using Scaffold 4.3.2 (Proteome Software Inc., Portland, OR, USA) and the pathway was analyzed using ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) from QIAGEN Inc. (Redwood City, CA, USA).

Cell cycle analysis using flow cytometry

The effect of treatment with DMXAA on the cell cycle was determined by flow cytometry as described previously.29 Briefly, A549 cells were treated with DMXAA at concentrations of 0.1, 1, and 10 μM for 24 hours. In separate experiments, A549 cells were treated with 10 μM DMXAA over a 72-hour period. The cells were suspended, fixed in 70% ethanol, washed in PBS, and resuspended in 1 mL of PBS containing 1 mg/mL RNase A and 50 μg/mL propidium iodide. The cells were incubated in the dark for 30 minutes at room temperature. Next, the cells were subject to cell cycle analysis using a flow cytometer (BD LSR II Analyzer; Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA, USA). The flow cytometer collected 10,000 events for analysis.

Measurement of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels

Intracellular levels of ROS were measured by a fluorometer using CM-H2DCFDA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell-permeant CM-H2DCFDA passively diffuses into cells and is retained in the cells after cleavage by intracellular esterases. Upon oxidation by ROS, the nonfluorescent CM-H2DCFDA is converted to highly fluorescent CM-DCF. Briefly, A549 cells were seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 1×104 cells/well. After treatment with DMXAA at 0.1, 1, and 10 μM for 48 hours, the cells were incubated with CM-H2DCFDA at 5 μM in PBS for 30 minutes. The fluorescence intensity was detected at wavelengths of 485 nm (excitation) and 530 nm (emission). The control cells were treated with vehicle only (0.05% dimethyl sulfoxide, v/v).

Western blotting analysis

A549 cells were washed with pre-cold PBS after 24-hour treatment with DMXAA at 0.1, 1, and 10 μM, lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation (RIPA) buffer containing the protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails, and centrifuged at 3,000× g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Protein concentrations were measured using a Pierce bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit. An equal amount of protein sample (30 μg) was resolved by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) sample loading buffer and electrophoresed on 12% SDS-PAGE minigel after thermal denaturation at 95°C for 5 minutes. The proteins were transferred onto an Immobilon polyvinylidene difluoride membrane at 400 mA for 1 hour at 4°C. Membranes were blocked with skim milk and probed with the indicated primary antibody overnight at 4°C and then blotted with appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibody. Visualization was performed using a ChemiDoc™ XRS system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) with enhanced chemiluminescence substrate, and the blots were analyzed using Image Lab 3.0 (Bio-Rad). The protein level was normalized to the matching densitometric value of the internal control β-actin.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons of multiple groups were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison procedure. Values of P<0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Assays were performed at least three times independently.

Results

Overview of proteomic response to DMXAA treatment in A549 cells

To reveal the potential molecular targets of DMXAA in the treatment of NSCLC, we conducted proteomic experiments to evaluate the interactome of DMXAA in A549 cells. There were 588 protein molecules identified as potential molecular targets of DMXAA in A549 cells, with 281 protein molecules being upregulated and 306 protein molecules being downregulated (Table 1). Subsequently, these proteins were subjected to IPA. The results showed that 256 signaling pathways and 184 cellular functional proteins were regulated by DMXAA in A549 cells (Tables 2 and 3). These functional proteins were involved in a number of important cellular processes, including cell proliferation, redox homeostasis, cell metabolism, cell migration and invasion, cell survival, and cell death. The signaling pathways included the G1 and G2 checkpoint regulation pathways, the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)signaling pathway, the 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling pathway, the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)-mediated oxidative stress response pathway, the epithelial adherens junction signaling pathway, regulation of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition signaling pathway, the nuclear factor-κB signaling pathway, and the apoptosis signaling pathway. The IPA results showed that the top ten targeted signaling pathways were the eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF) 2 signaling pathway, mTOR signaling pathway, eIF4 and p70S6K signaling pathway, epithelial adherens junction signaling pathway, remodeling of epithelial adherens junctions pathway, Nrf2-mediated oxidative stress response signaling pathway, RhoA signaling pathway, integrin signaling pathway, Rho-mediated regulation of actin-based motility signaling pathway, and Fcγ receptor-mediated phagocytosis signaling pathway (Table 2).

Table 1.

The 588 protein molecules regulated by DMXAA (5,6-dimethylxanthenone 4-acetic acid) in A549 cells

| Protein ID/symbol | Molecular weight (kDa) | Normalized heavy/light ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Q5VXJ5 | 93.115 | 0.036825 |

| P3C2G | 165.71 | 0.052938 |

| K1C10 | 58.826 | 0.090984 |

| K1C9 | 62.064 | 0.11756 |

| CB067 | 73.235 | 0.14108 |

| 1433F | 28.218 | 0.22201 |

| K1C14 | 51.561 | 0.33079 |

| K2C1 | 66.038 | 0.3831 |

| F5H2G2 | 52.909 | 0.43495 |

| K2C6B | 60.066 | 0.4391 |

| MANF | 20.7 | 0.52102 |

| F8VVM2 | 36.161 | 0.56761 |

| APMAP | 32.161 | 0.59766 |

| KRT85 | 55.802 | 0.59966 |

| B4DS13 | 64.805 | 0.60022 |

| F5H6E3 | 18.467 | 0.62881 |

| E9PEU4 | 47.204 | 0.65669 |

| E9PF80 | 25.3 | 0.65828 |

| F5H3I4 | 34.557 | 0.66102 |

| AL3A2 | 54.847 | 0.71801 |

| RAB1B | 22.171 | 0.71899 |

| F5GY65 | 28.494 | 0.71909 |

| ISG15 | 17.887 | 0.71998 |

| ACACA | 257.24 | 0.72374 |

| H90B4 | 58.264 | 0.72926 |

| K22E | 65.432 | 0.73358 |

| F5H0X6 | 50.435 | 0.73677 |

| F8VSA6 | 5.8668 | 0.73947 |

| AK1C1 | 36.788 | 0.74328 |

| RLA1 | 11.514 | 0.74644 |

| B4DKS8 | 37.255 | 0.75044 |

| TMOD3 | 39.594 | 0.75127 |

| BASP1 | 22.693 | 0.75558 |

| COX2 | 25.565 | 0.77367 |

| MARCS | 31.554 | 0.77387 |

| F8WD96 | 30 | 0.77581 |

| F5GX11 | 26.505 | 0.77779 |

| K2C8 | 53.704 | 0.78215 |

| K1C18 | 48.057 | 0.7824 |

| FKB1A | 11.951 | 0.78264 |

| B4E1K7 | 33.337 | 0.7835 |

| Q5TCU6 | 258.08 | 0.784 |

| RL29 | 17.752 | 0.78622 |

| F8W7P7 | 72.716 | 0.78997 |

| CHM4B | 24.95 | 0.79348 |

| E9PNH1 | 13.163 | 0.79972 |

| C9JW37 | 8.8333 | 0.79997 |

| CLCC1 | 39.837 | 0.80061 |

| B4E241 | 14.203 | 0.80205 |

| E9PH29 | 25.838 | 0.80339 |

| NNMT | 29.574 | 0.80458 |

| E7ESM6 | 101.21 | 0.80816 |

| RL36 | 12.254 | 0.80826 |

| ETFB | 27.843 | 0.81589 |

| F5GWR2 | 26.63 | 0.81598 |

| SC61B | 9.9743 | 0.81767 |

| ALDR | 35.853 | 0.81844 |

| AK1C2 | 36.735 | 0.81875 |

| GRHPR | 35.668 | 0.81892 |

| PON2 | 37.996 | 0.82002 |

| B7Z254 | 47.837 | 0.82473 |

| FRIL | 20.019 | 0.82759 |

| ATP5H | 18.491 | 0.82832 |

| B4DNJ5 | 43.368 | 0.82967 |

| HINT1 | 13.802 | 0.83028 |

| D6RDN3 | 4.1286 | 0.83128 |

| S10A4 | 11.728 | 0.83154 |

| CUL4B | 102.3 | 0.83195 |

| IDHC | 46.659 | 0.83275 |

| E9PDQ8 | 41.438 | 0.83332 |

| F8W914 | 37.144 | 0.83563 |

| ANXA4 | 35.882 | 0.83679 |

| S38A2 | 45.178 | 0.837 |

| F5H3T8 | 52.305 | 0.84001 |

| CDC37 | 44.468 | 0.84082 |

| A6NKT1 | 56.36 | 0.84176 |

| B4E0X8 | 66.231 | 0.84218 |

| SMRD2 | 55.238 | 0.84281 |

| F8WF81 | 14.275 | 0.84585 |

| RRBP1 | 108.63 | 0.84762 |

| SFPQ | 76.149 | 0.85165 |

| B4DRT4 | 17.326 | 0.85394 |

| B4DT43 | 30.025 | 0.85426 |

| KHDR1 | 44.027 | 0.8553 |

| E9PPQ5 | 20.723 | 0.85913 |

| D6RFI0 | 21.504 | 0.8613 |

| CDC42 | 21.258 | 0.86162 |

| COX41 | 19.576 | 0.86224 |

| EF1A2 | 50.47 | 0.86292 |

| SCMC1 | 51.354 | 0.86294 |

| C9J1T2 | 9.4459 | 0.86457 |

| GBG12 | 8.0061 | 0.8649 |

| E9PKD1 | 47.431 | 0.86946 |

| C9JPV1 | 12.063 | 0.86969 |

| BLVRB | 22.119 | 0.86996 |

| F5H4L5 | 32.734 | 0.87025 |

| K2C7 | 51.385 | 0.87164 |

| FKBP3 | 25.177 | 0.87335 |

| F5H1J1 | 38.739 | 0.87421 |

| ECH1 | 35.816 | 0.87427 |

| EFTU | 49.541 | 0.87443 |

| AL1A1 | 54.861 | 0.8745 |

| RAB5C | 23.482 | 0.8745 |

| D6RFH4 | 14.846 | 0.87485 |

| HSPB1 | 22.782 | 0.8751 |

| G6PD | 59.256 | 0.87609 |

| RB11A | 24.393 | 0.87617 |

| HCD2 | 26.923 | 0.8781 |

| CALX | 67.567 | 0.87892 |

| B1AHC7 | 64.075 | 0.87955 |

| F5H7G7 | 57.342 | 0.88015 |

| CAZA1 | 32.922 | 0.88192 |

| S100P | 10.4 | 0.88323 |

| AK1C3 | 36.853 | 0.88425 |

| CALR | 48.141 | 0.88565 |

| NOP2 | 88.972 | 0.88741 |

| HMGA1 | 11.676 | 0.88955 |

| F8W6V8 | 53.116 | 0.88964 |

| MIF | 12.476 | 0.89038 |

| USMG5 | 6.4575 | 0.89172 |

| PSB2 | 22.836 | 0.89303 |

| CBR1 | 30.375 | 0.8935 |

| SF3B3 | 44.605 | 0.89353 |

| PRDX5 | 17.031 | 0.89389 |

| LRRF1 | 82.688 | 0.89483 |

| B4DQJ8 | 51.872 | 0.89714 |

| CCNK | 41.293 | 0.9026 |

| FSCN1 | 54.529 | 0.90332 |

| CS021 | 75.356 | 0.90345 |

| B4E022 | 62.878 | 0.90614 |

| G3V5P4 | 16.916 | 0.90639 |

| PDIA4 | 72.932 | 0.90743 |

| KYNU | 52.351 | 0.90767 |

| PRS6B | 43.507 | 0.90881 |

| D6RF62 | 37.111 | 0.90967 |

| S10A6 | 10.18 | 0.91026 |

| F5GYB8 | 19.471 | 0.91104 |

| B3KUK2 | 19.73 | 0.91118 |

| PPIB | 23.742 | 0.91132 |

| D6REM6 | 88.358 | 0.91208 |

| F2Z3A5 | 40.127 | 0.91256 |

| R13AX | 12.134 | 0.91339 |

| SRSF1 | 22.46 | 0.91352 |

| GRP78 | 72.332 | 0.91353 |

| F2Z2J9 | 28.85 | 0.91353 |

| DNJA2 | 45.745 | 0.91354 |

| RS19 | 16.06 | 0.91521 |

| RL23A | 17.695 | 0.91665 |

| B7Z2V6 | 37.751 | 0.91676 |

| TMED9 | 27.277 | 0.91682 |

| IMUP | 8.5115 | 0.91694 |

| ENPL | 92.468 | 0.917 |

| LKHA4 | 57.299 | 0.91952 |

| SERC | 35.188 | 0.91971 |

| B1AM77 | 13.475 | 0.92027 |

| F5GYG9 | 76.233 | 0.92196 |

| D6RF44 | 12.64 | 0.92222 |

| B4E0R6 | 109.36 | 0.9266 |

| MDHM | 35.503 | 0.92738 |

| RS15 | 17.04 | 0.92751 |

| AL3A1 | 50.394 | 0.92795 |

| ATPB | 56.559 | 0.92872 |

| Q5T8U3 | 21.545 | 0.93039 |

| LGUL | 19.043 | 0.93096 |

| A8K318 | 59.177 | 0.93162 |

| CH10 | 10.932 | 0.93233 |

| CYTB | 11.139 | 0.9324 |

| C8KIM0 | 47.267 | 0.93263 |

| G3V5Q1 | 27.125 | 0.93343 |

| RS14 | 16.273 | 0.93344 |

| A6NN01 | 12.146 | 0.93348 |

| B7Z6M1 | 65.632 | 0.93372 |

| B3KUB4 | 31.857 | 0.93524 |

| NUDC | 38.242 | 0.9354 |

| FAS | 273.42 | 0.93581 |

| F5GWY2 | 58.615 | 0.93612 |

| SMD2 | 13.527 | 0.93633 |

| MDHC | 36.426 | 0.93699 |

| B4DIT7 | 68.648 | 0.93774 |

| D6RFJ8 | 47.291 | 0.9383 |

| E9PRQ6 | 15.159 | 0.93879 |

| FIS1 | 16.937 | 0.93901 |

| SAHH | 47.716 | 0.93913 |

| RLA2 | 11.665 | 0.93935 |

| AATM | 47.517 | 0.93946 |

| INF2 | 134.62 | 0.93976 |

| ATPA | 59.75 | 0.93996 |

| HNRPG | 42.331 | 0.94001 |

| EIF1 | 12.732 | 0.94212 |

| C9JPM4 | 14.553 | 0.94439 |

| ARF1 | 20.697 | 0.94471 |

| FLNB | 275.66 | 0.945 |

| NSF1C | 28.522 | 0.94549 |

| CDV3 | 22.079 | 0.94575 |

| E7EWF1 | 45.498 | 0.94724 |

| NDKB | 30.137 | 0.94913 |

| B1AH77 | 16.775 | 0.95 |

| H2A1J | 13.936 | 0.95043 |

| GDIR1 | 23.207 | 0.95062 |

| LDHB | 36.638 | 0.95153 |

| PA1B3 | 25.734 | 0.95246 |

| HNRPU | 88.979 | 0.95295 |

| G3V3I1 | 16.645 | 0.95297 |

| F2Z3F8 | 29.245 | 0.95333 |

| B4DVU3 | 88.161 | 0.95514 |

| HSP74 | 94.33 | 0.9556 |

| B4DKM5 | 27.478 | 0.95717 |

| SPRE | 28.048 | 0.9575 |

| B4DEM7 | 57.645 | 0.95821 |

| F5GX39 | 13.631 | 0.95862 |

| F5GZ27 | 85.64 | 0.96103 |

| PRDX1 | 22.11 | 0.96121 |

| PTBP1 | 57.221 | 0.96124 |

| F5H667 | 83.267 | 0.9617 |

| C9JLU1 | 16.996 | 0.96193 |

| B4DR70 | 44.812 | 0.96206 |

| SMD1 | 13.281 | 0.9621 |

| E7EU12 | 94.863 | 0.96289 |

| E7ETK5 | 30.611 | 0.96294 |

| B4DXW1 | 42.003 | 0.9639 |

| RCN1 | 38.89 | 0.96394 |

| PABP1 | 61.18 | 0.96407 |

| ANXA1 | 38.714 | 0.96409 |

| PARK7 | 19.891 | 0.96461 |

| H12 | 21.364 | 0.96469 |

| B7Z6A4 | 14.854 | 0.96516 |

| F8VNT9 | 14.265 | 0.96517 |

| E9PKZ0 | 22.389 | 0.96545 |

| F5H1S2 | 18.845 | 0.96676 |

| LRC59 | 34.93 | 0.96685 |

| UGDH | 55.023 | 0.96807 |

| TPIS | 26.669 | 0.96808 |

| ROA2 | 37.429 | 0.96842 |

| VDAC1 | 30.772 | 0.96869 |

| KPYM | 57.936 | 0.96936 |

| ANXA5 | 35.936 | 0.96942 |

| UBE2N | 17.138 | 0.96961 |

| ENOA | 47.168 | 0.97022 |

| S10AA | 11.203 | 0.97031 |

| HN1 | 16.014 | 0.97056 |

| PPIA | 18.012 | 0.9708 |

| RL12 | 17.818 | 0.97093 |

| F5GZ16 | 99.271 | 0.97167 |

| TCPA | 60.343 | 0.97176 |

| B4DRF4 | 36.43 | 0.97231 |

| ILF2 | 43.062 | 0.9728 |

| PDCD5 | 14.285 | 0.97482 |

| XPO2 | 22.67 | 0.97527 |

| RLA0 | 34.273 | 0.9763 |

| B4DZP4 | 45.004 | 0.97635 |

| F8W810 | 50.529 | 0.97677 |

| B3KQT9 | 54.102 | 0.97689 |

| E5RJR5 | 18.72 | 0.97695 |

| CAP1 | 51.901 | 0.97716 |

| A8K3Z3 | 44.784 | 0.97817 |

| B4DUR8 | 55.674 | 0.9785 |

| C9JV57 | 13.025 | 0.97853 |

| E7EMJ6 | 31.455 | 0.97864 |

| RS17L | 15.55 | 0.97906 |

| F5H8J3 | 75.177 | 0.97909 |

| RS9 | 22.591 | 0.97946 |

| LDHA | 36.688 | 0.97949 |

| HNRDL | 27.191 | 0.97974 |

| B7Z4V2 | 72.4 | 0.98075 |

| CKAP4 | 66.022 | 0.9808 |

| PDIA1 | 57.116 | 0.98205 |

| AT2A2 | 109.73 | 0.98343 |

| LPPRC | 157.9 | 0.98408 |

| TALDO | 37.54 | 0.98454 |

| PHB2 | 33.296 | 0.98512 |

| NBAS | 254.81 | 0.9852 |

| F5GY50 | 32.895 | 0.98539 |

| RS4X | 29.597 | 0.98585 |

| B4DPJ8 | 54.867 | 0.98615 |

| SYEP | 170.59 | 0.98633 |

| HNRPC | 27.821 | 0.98649 |

| EF1A1 | 50.14 | 0.98718 |

| D6RG13 | 25.608 | 0.98723 |

| AK1BA | 36.019 | 0.98779 |

| EF1G | 50.118 | 0.98818 |

| NAMPT | 55.52 | 0.98886 |

| F8VTY8 | 41.746 | 0.98925 |

| C9JTK6 | 12.302 | 0.9895 |

| TCPE | 59.67 | 0.98993 |

| RS18 | 17.718 | 0.99091 |

| FKBP4 | 51.804 | 0.99111 |

| MOES | 67.819 | 0.99187 |

| ARP2 | 44.76 | 0.99233 |

| RS5 | 22.876 | 0.99268 |

| RL11 | 20.124 | 0.99323 |

| F8VRG3 | 6.4352 | 0.99333 |

| C9JZ20 | 22.27 | 0.99398 |

| C9JB50 | 7.888 | 0.99449 |

| DX39A | 49.129 | 0.9946 |

| F5GYN4 | 28.05 | 0.99464 |

| B7Z795 | 47.709 | 0.99535 |

| B7Z4T9 | 54.804 | 0.99554 |

| TERA | 89.321 | 0.99599 |

| TCP4 | 14.395 | 0.99621 |

| B4DGN5 | 46.575 | 0.99641 |

| DBPA | 31.947 | 0.99662 |

| ADT2 | 32.852 | 0.99664 |

| CALM | 16.837 | 0.99736 |

| PGK1 | 44.614 | 0.99895 |

| ECHM | 31.387 | 0.99951 |

| MARE1 | 29.999 | 0.99998 |

| RS7 | 22.127 | 1 |

| API5 | 49.496 | 1.0009 |

| 1433G | 28.302 | 1.0011 |

| IQGA1 | 189.25 | 1.0015 |

| B4DDF7 | 64.181 | 1.0018 |

| LETM1 | 83.353 | 1.0024 |

| E7EWI9 | 34.102 | 1.0027 |

| D6RAS3 | 23.383 | 1.0035 |

| B4DLR8 | 22.793 | 1.0053 |

| PROF1 | 15.054 | 1.0054 |

| ALO17 | 118.43 | 1.0056 |

| RS3 | 26.688 | 1.0064 |

| RAB10 | 22.541 | 1.0066 |

| XRCC5 | 82.704 | 1.0076 |

| UBA1 | 117.85 | 1.0076 |

| CH60 | 61.054 | 1.0081 |

| A6NLM8 | 16.245 | 1.0083 |

| F8W0A9 | 40.793 | 1.0086 |

| NONO | 54.231 | 1.0087 |

| C9J7S3 | 19.969 | 1.0092 |

| C1QBP | 31.362 | 1.0099 |

| D6RAN4 | 20.874 | 1.0103 |

| PDC6I | 96.022 | 1.0107 |

| B4E3C2 | 17.094 | 1.0115 |

| MAP4 | 85.251 | 1.0117 |

| GSTP1 | 23.356 | 1.0129 |

| RL10A | 24.831 | 1.0129 |

| ACTS | 42.051 | 1.0141 |

| DHX9 | 140.96 | 1.0146 |

| PCBP1 | 37.497 | 1.0146 |

| F5H1W0 | 55.907 | 1.0147 |

| H33 | 15.328 | 1.0156 |

| RS6 | 28.68 | 1.0164 |

| G3V279 | 8.2033 | 1.0169 |

| D6RBT8 | 23.862 | 1.0179 |

| PRDX6 | 25.035 | 1.0193 |

| CAND1 | 136.37 | 1.0201 |

| TCTP | 19.595 | 1.0203 |

| B4DDG1 | 14.121 | 1.0204 |

| C9JCK5 | 18.607 | 1.0216 |

| PSB3 | 22.949 | 1.022 |

| MAP1B | 270.63 | 1.0222 |

| CN166 | 28.068 | 1.0223 |

| ACTN4 | 104.85 | 1.0228 |

| E9PQD7 | 25.211 | 1.0232 |

| E7EX53 | 15.722 | 1.0241 |

| B7ZAT2 | 52.717 | 1.026 |

| PAIRB | 42.426 | 1.0261 |

| E9PCY7 | 47.087 | 1.0262 |

| HNRPK | 48.562 | 1.0268 |

| B8ZZQ6 | 11.758 | 1.0272 |

| ACOC | 98.398 | 1.0274 |

| IF5A1 | 16.832 | 1.0284 |

| B4E335 | 39.226 | 1.0286 |

| PCNA | 28.768 | 1.0288 |

| A6NL93 | 9.5355 | 1.0294 |

| FLNA | 280.01 | 1.0304 |

| Q5JR95 | 21.879 | 1.0308 |

| C9J9K3 | 29.505 | 1.0309 |

| E7ETA0 | 34.028 | 1.0312 |

| TBB4B | 49.83 | 1.0315 |

| COF1 | 18.502 | 1.0318 |

| CLIC1 | 26.922 | 1.0322 |

| RINI | 49.973 | 1.0325 |

| 1433E | 29.174 | 1.033 |

| C9JF49 | 6.6566 | 1.0331 |

| RS13 | 17.222 | 1.0332 |

| GUAA | 76.715 | 1.0333 |

| AN32B | 22.276 | 1.0342 |

| E9PGI8 | 20.18 | 1.0342 |

| CLCA | 23.662 | 1.0345 |

| DYHC1 | 532.4 | 1.035 |

| E9PMD7 | 28.898 | 1.035 |

| 1433T | 27.764 | 1.0354 |

| E9PEN3 | 29.353 | 1.0367 |

| CLH1 | 187.89 | 1.0371 |

| E9PFH8 | 41.824 | 1.0377 |

| G3V3T3 | 21.126 | 1.0378 |

| GDIB | 50.663 | 1.0384 |

| PALLD | 73.321 | 1.04 |

| B1ALW1 | 9.4519 | 1.0404 |

| A8MUD9 | 24.433 | 1.0407 |

| NDKA | 17.149 | 1.0422 |

| Q2YDB7 | 16.541 | 1.0422 |

| S10AB | 11.74 | 1.0434 |

| QCR2 | 48.442 | 1.0437 |

| RS10 | 18.898 | 1.0446 |

| B7Z9L0 | 52.33 | 1.0449 |

| G3P | 36.053 | 1.046 |

| E7EQR4 | 65.578 | 1.046 |

| GBLP | 35.076 | 1.0464 |

| 1433B | 27.85 | 1.0465 |

| F5H0N0 | 37.406 | 1.0468 |

| G6PI | 63.146 | 1.0478 |

| E7EUG1 | 71.178 | 1.0499 |

| EF1B | 24.763 | 1.0504 |

| H4 | 11.367 | 1.0504 |

| BTF3 | 17.699 | 1.0505 |

| PGRC2 | 23.818 | 1.0508 |

| F8W118 | 24.694 | 1.051 |

| H32 | 15.388 | 1.0514 |

| DYL2 | 10.35 | 1.0516 |

| E9PEC0 | 32.819 | 1.0516 |

| ALDOA | 39.42 | 1.0522 |

| EF2 | 95.337 | 1.0523 |

| TBA1C | 49.895 | 1.0528 |

| IPYR | 32.66 | 1.054 |

| F8VZJ2 | 15.016 | 1.0547 |

| PRS10 | 44.172 | 1.0559 |

| F8W7K3 | 282.14 | 1.0567 |

| H2B1L | 13.952 | 1.0571 |

| G3V5B3 | 19.154 | 1.058 |

| HSP71 | 70.051 | 1.0588 |

| B2REB8 | 30.992 | 1.0591 |

| B4DR63 | 41.167 | 1.0595 |

| RL22 | 14.787 | 1.0599 |

| ACTN1 | 103.06 | 1.06 |

| B4E2S7 | 39.811 | 1.0605 |

| G3V5M3 | 9.2044 | 1.0608 |

| C9JU56 | 13.336 | 1.061 |

| B7Z1N6 | 35.423 | 1.0625 |

| CAN2 | 79.994 | 1.0631 |

| F8VWC5 | 18.091 | 1.0641 |

| SODC | 15.936 | 1.0644 |

| TBA1B | 50.151 | 1.0646 |

| RS16 | 16.445 | 1.065 |

| C9JD32 | 9.6694 | 1.0658 |

| VINC | 116.72 | 1.0668 |

| RS25 | 13.742 | 1.0671 |

| A4D177 | 20.811 | 1.0685 |

| Q5HYE7 | 20.42 | 1.0694 |

| GLRX3 | 37.432 | 1.0699 |

| B4E3E8 | 71.354 | 1.0717 |

| LEG1 | 14.716 | 1.0729 |

| A8K8G0 | 22.964 | 1.0736 |

| TPM4 | 28.521 | 1.0744 |

| F5H897 | 74.267 | 1.0744 |

| E9PJH8 | 15.461 | 1.0749 |

| E9PNR9 | 18.297 | 1.0749 |

| F8W181 | 25.892 | 1.0756 |

| AIBP | 20.43 | 1.0758 |

| HSP7C | 70.897 | 1.076 |

| CPNS1 | 28.315 | 1.0764 |

| ANXA2 | 38.604 | 1.0765 |

| 1433Z | 27.745 | 1.077 |

| HS90A | 84.659 | 1.0771 |

| C9JKI3 | 15.928 | 1.0779 |

| HNRPL | 64.132 | 1.0786 |

| NPM | 29.464 | 1.0788 |

| AHNK | 629.09 | 1.079 |

| F8VYX6 | 48.46 | 1.0796 |

| EF1D | 31.121 | 1.0797 |

| GTF2I | 107.97 | 1.0801 |

| D6R9P3 | 30.302 | 1.0806 |

| PSME1 | 28.723 | 1.0815 |

| Q8N1C0 | 59.549 | 1.0838 |

| ADT3 | 32.866 | 1.0863 |

| B4DY66 | 19.152 | 1.087 |

| PLEC | 531.78 | 1.0874 |

| E7EX81 | 65.881 | 1.0877 |

| C9J712 | 9.7982 | 1.088 |

| F6RFD5 | 15.397 | 1.0883 |

| PSME2 | 27.401 | 1.09 |

| HS90B | 83.263 | 1.0909 |

| F5H4D6 | 31.451 | 1.0914 |

| B4DR31 | 58.162 | 1.0921 |

| RS12 | 14.515 | 1.0928 |

| TADBP | 27.972 | 1.0948 |

| B6EAT9 | 37.277 | 1.0972 |

| RS15A | 14.839 | 1.0986 |

| RS20 | 13.373 | 1.1055 |

| B4E3S0 | 41.603 | 1.108 |

| RS28 | 7.8409 | 1.1109 |

| LMNA | 74.139 | 1.1139 |

| ROA1 | 29.386 | 1.1144 |

| PGRC1 | 21.671 | 1.1155 |

| C9JHS6 | 5.6564 | 1.1161 |

| Q5TA01 | 20.938 | 1.1186 |

| TIF1B | 79.473 | 1.1193 |

| HNRPM | 73.62 | 1.1205 |

| RL19 | 23.466 | 1.1208 |

| TXNL1 | 32.251 | 1.1218 |

| RAN | 24.423 | 1.1235 |

| F8W7C6 | 18.592 | 1.1241 |

| G3XAI4 | 119.77 | 1.1248 |

| IF4A1 | 46.153 | 1.1252 |

| VIME | 53.651 | 1.1263 |

| F5H0T1 | 59.777 | 1.1272 |

| C9JFR7 | 11.333 | 1.1279 |

| E7EPB3 | 14.558 | 1.1287 |

| DDX5 | 69.147 | 1.1298 |

| F5H6Q2 | 13.789 | 1.1306 |

| ITB1 | 87.445 | 1.1347 |

| B4DP24 | 29.485 | 1.135 |

| TAGL2 | 22.391 | 1.1361 |

| B3KS31 | 41.952 | 1.1361 |

| SPTB2 | 251.39 | 1.1366 |

| G3V531 | 44.06 | 1.1371 |

| PYGB | 96.695 | 1.141 |

| PRP8 | 273.6 | 1.1413 |

| DNJA1 | 44.868 | 1.1421 |

| TBB2B | 49.953 | 1.1428 |

| HNRPQ | 58.735 | 1.1433 |

| B7Z9C4 | 35.253 | 1.1444 |

| IMB1 | 97.169 | 1.1455 |

| F8W0G4 | 16.637 | 1.1455 |

| KINH | 109.68 | 1.1465 |

| F8WBE5 | 8.8809 | 1.1471 |

| METK2 | 43.66 | 1.1482 |

| PTRF | 33.362 | 1.1512 |

| K6PP | 85.595 | 1.1514 |

| B7Z2S5 | 60.021 | 1.1531 |

| B2RDM2 | 36.177 | 1.1541 |

| B4DSC0 | 14.503 | 1.1554 |

| ECHA | 82.999 | 1.1555 |

| F8VPF3 | 14.436 | 1.1565 |

| B0V3J0 | 26.101 | 1.159 |

| F8VR50 | 9.7261 | 1.1619 |

| B3KTM6 | 28.044 | 1.1649 |

| BAF | 10.058 | 1.1652 |

| IF2A | 36.112 | 1.1676 |

| Q5H907 | 55.795 | 1.1682 |

| TPM1 | 32.876 | 1.1693 |

| IF6 | 26.599 | 1.1727 |

| SYTC | 83.434 | 1.1736 |

| Q75MH1 | 12.985 | 1.1814 |

| B4DZI8 | 99.045 | 1.1821 |

| Q5T4L4 | 7.3564 | 1.1834 |

| Q5T093 | 13.439 | 1.1877 |

| H31 | 15.404 | 1.1882 |

| Q5VU59 | 27.174 | 1.1982 |

| TBB4A | 49.585 | 1.1987 |

| MYH9 | 226.53 | 1.2006 |

| IMA2 | 57.861 | 1.2074 |

| GLSK | 65.459 | 1.2081 |

| Q5T7C4 | 18.311 | 1.2156 |

| C9JFK9 | 34.759 | 1.2186 |

| G3V153 | 70.353 | 1.223 |

| PSA7 | 20.193 | 1.2257 |

| E5RHS5 | 26.635 | 1.2275 |

| 1433S | 27.774 | 1.2337 |

| F2Z3D0 | 8.1111 | 1.238 |

| PSA4 | 29.483 | 1.2384 |

| B7Z8D3 | 14.761 | 1.2419 |

| B4E2Z3 | 55.939 | 1.2474 |

| E9PP21 | 16.94 | 1.25 |

| ROA0 | 30.84 | 1.2609 |

| B4DMT5 | 33.24 | 1.2628 |

| C9K0U8 | 14.131 | 1.2706 |

| UBP15 | 112.42 | 1.2708 |

| ML12A | 19.794 | 1.2917 |

| LASP1 | 29.717 | 1.2975 |

| A8MUB1 | 48.328 | 1.2985 |

| APOL2 | 37.092 | 1.304 |

| HMOX1 | 32.818 | 1.3048 |

| PSA3 | 27.647 | 1.312 |

| TYB10 | 5.0256 | 1.3172 |

| Q5T4B6 | 5.1127 | 1.3249 |

| C9IZ41 | 17.054 | 1.3258 |

| F5H4W0 | 44.933 | 1.331 |

| LAT1 | 55.01 | 1.3337 |

| PSB1 | 26.489 | 1.335 |

| B4DPJ6 | 17.473 | 1.34 |

| F5H0C8 | 34.762 | 1.3474 |

| TBB3 | 50.432 | 1.3583 |

| TBAL3 | 45.517 | 1.4041 |

| DUT | 17.748 | 1.4353 |

| F8WC15 | 47.819 | 1.4365 |

| PLIN3 | 28.157 | 1.4972 |

| F5GWR9 | 22.218 | 1.499 |

| C9JL85 | 5.7044 | 1.5138 |

| E7ERP8 | 31.801 | 1.5322 |

| AAAT | 56.598 | 1.6533 |

| RBM3 | 17.17 | 1.7162 |

| B4DP11 | 16.476 | 1.8007 |

| MYOF | 179.55 | 1.9046 |

| SRP14 | 14.57 | 1.9407 |

| PLP2 | 16.691 | NaN |

| HNF4A | 52.784 | NaN |

| YLPM1 | 241.64 | NaN |

| E7EWZ6 | 111.13 | NaN |

| Q5TCU3 | 32.814 | NaN |

Table 2.

Signaling pathways for target proteins regulated by DMXAA (5,6-dimethylxanthenone 4-acetic acid) in A549 cells

| Ingenuity canonical pathways | −LogP | Molecules |

|---|---|---|

| eIF2 signaling | 2.11E01 | EIF3C, AKT2, RPS3A, RPS27, RPS2, RPL17, RPS8, RPL23, EIF3E, RPL9, RPL7, RPL15, RPL14, RPL8, EIF3F, RPL7A, RPL28, RPS26, RPL5, RPL10, PPP1CA, RPL31, RPL18, RPL13, RPSA |

| mTOR signaling | 7.52E00 | AKT2, EIF3C, RPS3A, RPS27, RPS2, RPS8, EIF3E, EIF3F, PPP2R1A, RPS26, RHOA, RPSA, EIF4B |

| Regulation of eIF4 and p70S6K signaling | 6.82E00 | AKT2, EIF3F, PPP2R1A, EIF3C, RPS3A, RPS26, RPS27, RPS2, RPS8, EIF3E, RPSA |

| Epithelial adherens junction signaling | 5.87E00 | AKT2, ACTR3, TUBB6, MYL6, ACTB, RHOA, TUBA4A, CTNNA1, ARPC3, ZYX |

| Remodeling of epithelial adherens junctions | 5.43E00 | ACTR3, TUBB6, ACTB, TUBA4A, CTNNA1, ARPC3, ZYX |

| Nrf2-mediated oxidative stress response | 5.05E00 | GSR, SOD2, STIP1, ACTB, NQO1, CCT7, TXN, PTPLAD1, TXNRD1, GSTO1 |

| RhoA signaling | 4.66E00 | ACTR3, CFL2, MYL6, EZR, ACTB, RHOA, PFN2, ARPC3 |

| Integrin signaling | 4.62E00 | RAC2, AKT2, ACTR3, ARF4, ACTB, RHOA, CAV1, ARPC3, ZYX, TLN1 |

| Regulation of actin-based motility by Rho | 4.59E00 | RAC2, ACTR3, MYL6, ACTB, RHOA, PFN2, ARPC3 |

| Fcγ receptor-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages and monocytes | 4.53E00 | RAC2, AKT2, ACTR3, EZR, ACTB, ARPC3, TLN1 |

| Actin cytoskeleton signaling | 4.35E00 | RAC2, ACTR3, CFL2, MYL6, EZR, ACTB, RHOA, PFN2, ARPC3, TLN1 |

| Axonal guidance signaling | 4.17E00 | DPYSL2, RAC2, AKT2, MYL6, PDIA3, TUBA4A, ACTR3, TUBB6, CFL2, RHOA, RTN4, ARPC3, PFN2, PSMD14 |

| Purine nucleotides de novo biosynthesis II | 3.88E00 | IMPDH2, PAICS, ATIC |

| Germ cell-Sertoli cell junction signaling | 3.83E00 | RAC2, TUBB6, CFL2, ACTB, RHOA, TUBA4A, CTNNA1, ZYX |

| Protein ubiquitination pathway | 3.77E00 | PSMA6, PSMC1, UBE2L3, HSPA9, PSMD14, PSMA1, UBC, PSMA2, SKP1, PSMC5 |

| RhoGDI signaling | 3.6E00 | ACTR3, CFL2, MYL6, EZR, ACTB, RHOA, CD44, ARPC3 |

| Inosine-5′-phosphate biosynthesis II | 3.57E00 | PAICS, ATIC |

| Vitamin C transport | 3.55E00 | TXN, TXNRD1, GSTO1 |

| Huntington’s disease signaling | 3.44E00 | TGM2, CTSD, AKT2, CYCS, CPLX2, HSPA9, POLR2H, UBC, PSME3 |

| RAN signaling | 3.28E00 | TNPO1, XPO1, IPO5 |

| Thioredoxin pathway | 2.88E00 | TXN, TXNRD1 |

| Superoxide radical degradation | 2.88E00 | SOD2, NQO1 |

| Gluconeogenesis I | 2.78E00 | ENO2, ME1, ALDOC |

| Integrin linked kinase signaling | 2.69E00 | AKT2, PPP2R1A, CFL2, MYL6, ACTB, RHOA, NACA |

| Aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling | 2.65E00 | TGM2, CTSD, NEDD8, NQO1, PTGES3, GSTO1 |

| Leukocyte extravasation signaling | 2.54E00 | RAC2, MYL6, EZR, ACTB, RHOA, CD44, CTNNA1 |

| Rac signaling | 2.5E00 | ACTR3, CFL2, RHOA, CD44, ARPC3 |

| Gap junction signaling | 2.43E00 | AKT2, TUBB6, PDIA3, ACTB, CAV1, TUBA4A |

| Pentose phosphate pathway | 2.33E00 | PGD, TKT |

| Caveolar-mediated endocytosis signaling | 2.31E00 | ARCN1, ACTB, CAV1, COPB2 |

| Tight junction signaling | 2.28E00 | AKT2, PPP2R1A, MYL6, ACTB, RHOA, CTNNA1 |

| Ephrin receptor signaling | 2.19E00 | RAC2, AKT2, ACTR3, CFL2, RHOA, ARPC3 |

| Ceramide signaling | 2.15E00 | CTSD, AKT2, PPP2R1A, CYCS |

| Signaling by Rho family GTPases | 2.15E00 | ACTR3, CFL2, MYL6, EZR, ACTB, RHOA, ARPC3 |

| Sertoli cell-Sertoli cell junction signaling | 2.13E00 | AKT2, TUBB6, ACTB, CAV1, TUBA4A, CTNNA1 |

| Virus entry via endocytic pathways | 1.99E00 | RAC2, ACTB, CAV1, TFRC |

| Antioxidant action of vitamin C | 1.86E00 | PDIA3, TXN, TXNRD1, GSTO1 |

| Semaphorin signaling in neurons | 1.86E00 | DPYSL2, CFL2, RHOA |

| Actin nucleation by ARP-WASP complex | 1.79E00 | ACTR3, RHOA, ARPC3 |

| Glutamate biosynthesis II | 1.72E00 | GLUD1 |

| Glutamate degradation X | 1.72E00 | GLUD1 |

| Glycolysis I | 1.63E00 | ENO2, ALDOC |

| Mitochondrial dysfunction | 1.62E00 | GSR, PRDX3, SOD2, CYCS, VDAC2 |

| 14-3-3-mediated signaling | 1.59E00 | AKT2, TUBB6, PDIA3, TUBA4A |

| Pyrimidine ribonucleotide interconversion | 1.57E00 | CMPK1, CTPS1 |

| Ascorbate recycling (cytosolic) | 1.55E00 | GSTO1 |

| Glutathione redox reactions II | 1.55E00 | GSR |

| Thyroid hormone biosynthesis | 1.55E00 | CTSD |

| 4-aminobutyrate degradation I | 1.55E00 | SUCLG2 |

| Pigment epithelium derived factor signaling | 1.52E00 | AKT2, SOD2, RHOA |

| Pyrimidine ribonucleotide biosynthesis de novo | 1.51E00 | CMPK1, CTPS1 |

| Clathrin-mediated endocytosis signaling | 1.5E00 | ACTR3, ACTB, TFRC, ARPC3, UBC |

| Ephrin B signaling | 1.49E00 | RAC2, CFL2, RHOA |

| Breast cancer regulation by stathmin1 | 1.45E00 | PPP2R1A, TUBB6, RHOA, TUBA4A, PPP1CA |

| Arsenate detoxification I (glutaredoxin) | 1.43E00 | GSTO1 |

| Uracil degradation II (reductive) | 1.43E00 | DPYSL2 |

| 2-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex | 1.43E00 | DLST |

| Thymine degradation | 1.43E00 | DPYSL2 |

| Cell cycle regulation by BTG family proteins | 1.36E00 | PPP2R1A, PRMT1 |

| tRNA splicing | 1.36E00 | TSEN34, APEX1 |

| Pentose phosphate pathway (oxidative branch) | 1.33E00 | PGD |

| Glutamate degradation III (via 4-aminobutyrate) | 1.33E00 | SUCLG2 |

| Focal adhesion kinase signaling | 1.3E00 | AKT2, ACTB, TLN1 |

| Docosahexaenoic acid signaling | 1.28E00 | AKT2, CYCS |

| tRNA charging | 1.28E00 | RARS, DARS |

| Arginine biosynthesis IV | 1.25E00 | GLUD1 |

| Pentose phosphate pathway (nonoxidative branch) | 1.25E00 | TKT |

| Citrulline-nitric oxide cycle | 1.25E00 | CAV1 |

| Death receptor signaling | 1.24E00 | ACIN1, CYCS, ACTB |

| Mechanisms of viral exit from host cells | 1.24E00 | ACTB, XPO1 |

| Telomerase signaling | 1.17E00 | AKT2, PPP2R1A, PTGES3 |

| Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α signaling | 1.13E00 | AKT2, CAV1, APEX1 |

| Cdc42 signaling | 1.12E00 | ACTR3, CFL2, MYL6, ARPC3 |

| Ephrin A signaling | 1.12E00 | CFL2, RHOA |

| Wnt/β-catenin signaling | 1.11E00 | AKT2, PPP2R1A, CD44, UBC |

| Prostanoid biosynthesis | 1.08E00 | PTGES3 |

| Sucrose degradation V (mammalian) | 1.08E00 | ALDOC |

| Ketolysis | 1.08E00 | ACAT1 |

| Sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling | 1.07E00 | AKT2, PDIA3, RHOA |

| Retinoic acid receptor activation | 1.06E00 | AKT2, RPL7A, PSMC5, PRMT1 |

| Endometrial cancer signaling | 1.06E00 | AKT2, CTNNA1 |

| Ketogenesis | 1.04E00 | ACAT1 |

| Production of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in macrophages | 1.03E00 | AKT2, PPP2R1A, RHOA, PPP1CA |

| Lymphotoxin β receptor signaling | 1.03E00 | AKT2, CYCS |

| Hereditary breast cancer signaling | 1.02E00 | AKT2, POLR2H, UBC |

| Glutaryl-CoA degradation | 1E00 | ACAT1 |

| Gα12/13 signaling | 9.98E-01 | AKT2, MYL6, RHOA |

| Glioma invasiveness signaling | 9.91E-01 | RHOA, CD44 |

| Regulation of cellular mechanics by calpain protease | 9.91E-01 | EZR, TLN1 |

| CD28 signaling in T-helper cells | 9.9E-01 | AKT2, ACTR3, ARPC3 |

| ERK/MAPK signaling | 9.87E-01 | RAC2, PPP2R1A, TLN1, PPP1CA |

| Glucocorticoid receptor signaling | 9.85E-01 | HMGB1, AKT2, HSPA9, POLR2H, PTGES3 |

| p70S6K signaling | 9.82E-01 | AKT2, PPP2R1A, PDIA3 |

| Myc-mediated apoptosis signaling | 9.79E-01 | AKT2, CYCS |

| High-mobility group box 1 signaling | 9.74E-01 | HMGB1, AKT2, RHOA |

| Thrombin signaling | 9.63E-01 | AKT2, MYL6, PDIA3, RHOA |

| Induction of apoptosis by human immunodeficiency virus-1 | 9.54E-01 | CYCS, SLC25A3 |

| Xenobiotic metabolism signaling | 9.34E-01 | PPP2R1A, CES1, NQO1, PTGES3, GSTO1 |

| Cell cycle: G1/S checkpoint regulation | 9.08E-01 | RPL5, SKP1 |

| Cellular effects of sildenafil (Viagra®) | 9.05E-01 | MYL6, PDIA3, ACTB |

| Isoleucine degradation I | 9.03E-01 | ACAT1 |

| Urate biosynthesis/inosine 5′-phosphate degradation | 9.03E-01 | IMPDH2 |

| Mevalonate pathway I | 9.03E-01 | ACAT1 |

| Hypoxia signaling in the cardiovascular system | 8.97E-01 | UBE2L3, NQO1 |

| Cardiac β-adrenergic signaling | 8.76E-01 | PPP2R1A, PPP1CA, APEX1 |

| Chondroitin sulfate degradation (metazoa) | 8.75E-01 | CD44 |

| Superpathway of citrulline metabolism | 8.75E-01 | CAV1 |

| Agrin interactions at neuromuscular junction | 8.55E-01 | RAC2, ACTB |

| Granzyme B signaling | 8.49E-01 | CYCS |

| Dermatan sulfate degradation (metazoa) | 8.49E-01 | CD44 |

| Methionine degradation I (to homocysteine) | 8.49E-01 | PRMT1 |

| Parkinson’s signaling | 8.49E-01 | CYCS |

| Renal cell carcinoma signaling | 8.35E-01 | AKT2, UBC |

| Small-cell lung cancer signaling | 8.35E-01 | AKT2, CYCS |

| Endothelial nitric oxide synthase signaling | 8.22E-01 | AKT2, HSPA9, CAV1 |

| Synaptic long-term depression | 8.16E-01 | PPP2R1A, PDIA3, CAV1 |

| Leptin signaling in obesity | 8.07E-01 | AKT2, PDIA3 |

| Glutathione redox reactions I | 8.02E-01 | GSR |

| Superpathway of geranylgeranyldiphosphate biosynthesis I (via mevalonate) | 8.02E-01 | ACAT1 |

| Cysteine biosynthesis III (mammalia) | 8.02E-01 | PRMT1 |

| Glioblastoma multiforme signaling | 7.91E-01 | AKT2, PDIA3, RHOA |

| DNA damage-induced 14-3-3σ signaling | 7.8E-01 | AKT2 |

| Cyclins and cell cycle regulation | 7.71E-01 | PPP2R1A, SKP1 |

| Dopamine receptor signaling | 7.71E-01 | PPP2R1A, PPP1CA |

| Granzyme A signaling | 7.6E-01 | APEX1 |

| Purine nucleotide degradation II (aerobic) | 7.6E-01 | IMPDH2 |

| Tryptophan degradation III (eukaryotic) | 7.6E-01 | ACAT1 |

| C-X-C-motif chemokine receptor-4 signaling | 7.55E-01 | AKT2, MYL6, RHOA |

| Polyamine regulation in colon cancer | 7.23E-01 | PSME3 |

| Pyrimidine deoxyribonucleotide biosynthesis I de novo | 7.23E-01 | CMPK1 |

| Phospholipase C signaling | 7.15E-01 | TGM2, PEBP1, MYL6, RHOA |

| Thyroid hormone receptor/retinoid X receptor activation | 7.14E-01 | AKT2, ME1 |

| Tricarboxylic acid cycle II (eukaryotic) | 7.05E-01 | DLST |

| Dopamine-DARPP32 feedback in cAMP signaling | 7.05E-01 | PPP2R1A, PDIA3, PPP1CA |

| Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 signaling in cytotoxic T lymphocytes | 6.91E-01 | AKT2, PPP2R1A |

| Gβγ signaling | 6.91E-01 | AKT2, CAV1 |

| Ultraviolet-induced MAPK signaling | 6.91E-01 | CYCS, PDIA3 |

| Interleukin-22 signaling | 6.89E-01 | AKT2 |

| Tumoricidal function of hepatic natural killer cells | 6.89E-01 | CYCS |

| Crosstalk between dendritic cells and natural killer cells | 6.84E-01 | ACTB, TLN1 |

| p21-activated kinase signaling | 6.84E-01 | CFL2, MYL6 |

| Apoptosis signaling | 6.84E-01 | ACIN1, CYCS |

| Triacylglycerol degradation | 6.73E-01 | CES1 |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor signaling | 6.7E-01 | AKT2, ACTB |

| Lipid antigen presentation by CD1 | 6.58E-01 | PDIA3 |

| Antiproliferative role of TOB in T-cell signaling | 6.58E-01 | SKP1 |

| cAMP response element-binding protein signaling in neurons | 6.54E-01 | AKT2, PDIA3, POLR2H |

| Salvage pathways of pyrimidine ribonucleotides | 6.49E-01 | AKT2, CMPK1 |

| Interleukin-15 production | 6.44E-01 | TWF1 |

| B-cell receptor signaling | 6.3E-01 | RAC2, AKT2, CFL2 |

| Glutathione-mediated detoxification | 6.3E-01 | GSTO1 |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis signaling | 6.22E-01 | CYCS, SSR4 |

| Calcium signaling | 6.21E-01 | MYL6, TPM3, ASPH |

| Superpathway of cholesterol biosynthesis | 6.16E-01 | ACAT1 |

| CDK5 signaling | 6.16E-01 | PPP2R1A, PPP1CA |

| Nitric oxide signaling in the cardiovascular system | 6.16E-01 | AKT2, CAV1 |

| Interleukin-8 signaling | 5.98E-01 | RAC2, AKT2, RHOA |

| Paxillin signaling | 5.98E-01 | ACTB, TLN1 |

| Superpathway of methionine degradation | 5.91E-01 | PRMT1 |

| Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated apoptosis of target cells | 5.8E-01 | CYCS |

| Molecular mechanisms of cancer | 5.74E-01 | RAC2, AKT2, CYCS, RHOA, CTNNA1 |

| Agranulocyte adhesion and diapedesis | 5.73E-01 | MYL6, EZR, ACTB |

| Nerve growth factor signaling | 5.68E-01 | AKT2, RHOA |

| N-formyl-l-methionyl-l-leucyl-phenylalanine signaling in neutrophils | 5.63E-01 | ACTR3, ARPC3 |

| Fc epsilon RI signaling | 5.57E-01 | RAC2, AKT2 |

| TNF-related weak inducer of apoptosis signaling | 5.57E-01 | CYCS |

| Inhibition of angiogenesis by thrombospondin 1 | 5.57E-01 | AKT2 |

| Retinol biosynthesis | 5.57E-01 | CES1 |

| Natural killer cell signaling | 5.52E-01 | RAC2, AKT2 |

| Role of tissue factor in cancer | 5.52E-01 | AKT2, CFL2 |

| Triacylglycerol biosynthesis | 5.47E-01 | ELOVL1 |

| Stearate biosynthesis I (animals) | 5.47E-01 | ELOVL1 |

| Nucleotide excision repair pathway | 5.47E-01 | POLR2H |

| Antigen presentation pathway | 5.26E-01 | PDIA3 |

| Protein kinase A signaling | 5.21E-01 | MYL6, PDIA3, RHOA, PPP1CA, APEX1 |

| CCR3 signaling in eosinophils | 5.15E-01 | CFL2, RHOA |

| Phosphatase and tensin homolog signaling | 5.1E-01 | RAC2, AKT2 |

| Netrin signaling | 5.07E-01 | RAC2 |

| Synaptic long-term potentiation | 5.05E-01 | PDIA3, PPP1CA |

| P2Y purigenic receptor signaling pathway | 5.05E-01 | AKT2, PDIA3 |

| Sperm motility | 5.01E-01 | TWF1, PDIA3 |

| Role of protein kinase R in interferon induction and antiviral response | 4.98E-01 | CYCS |

| PI3K/Akt signaling | 4.86E-01 | AKT2, PPP2R1A |

| Melanoma signaling | 4.81E-01 | AKT2 |

| Estrogen receptor signaling | 4.68E-01 | POLR2H, HNRNPD |

| PI3K signaling in B lymphocytes | 4.64E-01 | AKT2, PDIA3 |

| Ovarian cancer signaling | 4.51E-01 | AKT2, CD44 |

| Cardiac hypertrophy signaling | 4.49E-01 | MYL6, PDIA3, RHOA |

| Role of Oct4 in mammalian embryonic stem cell pluripotency | 4.49E-01 | PHB |

| Macrophage stimulating protein-RON signaling pathway | 4.49E-01 | ACTB |

| Insulin receptor signaling | 4.39E-01 | AKT2, PPP1CA |

| Relaxin signaling | 4.35E-01 | AKT2, APEX1 |

| 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase signaling | 4.35E-01 | AKT2, PPP2R1A |

| TNF receptor-1 signaling | 4.27E-01 | CYCS |

| Cell cycle: G2/M DNA damage checkpoint regulation | 4.27E-01 | SKP1 |

| Assembly of RNA polymerase II complex | 4.2E-01 | POLR2H |

| Amyloid processing | 4.14E-01 | AKT2 |

| CD27 signaling in lymphocytes | 4.07E-01 | CYCS |

| Interleukin-2 signaling | 4.01E-01 | AKT2 |

| Gαq signaling | 3.89E-01 | AKT2, RHOA |

| Role of checkpoint kinase 1 proteins in cell cycle checkpoint control | 3.89E-01 | PPP2R1A |

| Epidermal growth factor signaling | 3.83E-01 | AKT2 |

| Nur77 signaling in T lymphocytes | 3.77E-01 | CYCS |

| Phospholipases | 3.77E-01 | PDIA3 |

| Aldosterone signaling in epithelial cells | 3.72E-01 | PDIA3, HSPA9 |

| Tec kinase signaling | 3.53E-01 | ACTB, RHOA |

| Estrogen-dependent breast cancer signaling | 3.5E-01 | AKT2 |

| Granulocyte-monocyte colony stimulating factor signaling | 3.5E-01 | AKT2 |

| Retinoic acid mediated apoptosis signaling | 3.4E-01 | CYCS |

| Interleukin-17A signaling in airway cells | 3.4E-01 | AKT2 |

| Pyridoxal 5′-phosphate salvage pathway | 3.4E-01 | AKT2 |

| Non-small cell lung cancer signaling | 3.35E-01 | AKT2 |

| Interleukin-15 signaling | 3.3E-01 | AKT2 |

| Angiopoietin signaling | 3.3E-01 | AKT2 |

| Mitotic roles of polo-like kinase | 3.3E-01 | PPP2R1A |

| Role of PI3K/Akt signaling in the pathogenesis of influenza | 3.3E-01 | AKT2 |

| Pregnane X receptor/9-cis retinoic acid receptor activation | 3.25E-01 | AKT2 |

| Erythropoietin signaling | 3.25E-01 | AKT2 |

| Gamma aminobutyric acid receptor signaling | 3.25E-01 | UBC |

| Role of MAPK signaling in the pathogenesis of influenza | 3.21E-01 | AKT2 |

| Macropinocytosis signaling | 3.21E-01 | RHOA |

| Acute phase response signaling | 3.2E-01 | AKT2, SOD2 |

| Role of NFAT in regulation of immune response | 3.15E-01 | AKT2, XPO1 |

| Endothelin-1 signaling | 3.12E-01 | PDIA3, CAV1 |

| Melatonin signaling | 3.12E-01 | PDIA3 |

| Interleukin-3 signaling | 3.07E-01 | AKT2 |

| Chemokine signaling | 3.07E-01 | RHOA |

| Interleukin-17 signaling | 3.03E-01 | AKT2 |

| Janus kinase/Stat signaling | 3.03E-01 | AKT2 |

| Nuclear factor kappaB activation by viruses | 2.99E-01 | AKT2 |

| FLT3 signaling in hematopoietic progenitor cells | 2.95E-01 | AKT2 |

| Toll-like receptor signaling | 2.95E-01 | UBC |

| Dendritic cell maturation | 2.94E-01 | AKT2, PDIA3 |

| Role of NFAT in cardiac hypertrophy | 2.94E-01 | AKT2, PDIA3 |

| Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1 signaling | 2.91E-01 | AKT2 |

| HER-2 signaling in breast cancer | 2.87E-01 | AKT2 |

| VEGF family ligand-receptor interactions | 2.87E-01 | AKT2 |

| Interleukin-4 signaling | 2.87E-01 | AKT2 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia signaling | 2.83E-01 | AKT2 |

| Platelet-derived growth factor signaling | 2.83E-01 | CAV1 |

| Regulation of the epithelial to mesenchymal transition pathway | 2.81E-01 | AKT2, RHOA |

| 1,25(OH)2D/retinoid X receptor | 2.79E-01 | PSMC5 |

| Role of macrophages, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells in rheumatoid arthritis | 2.68E-01 | AKT2, PDIA3, RHOA |

| Prostate cancer signaling | 2.65E-01 | AKT2 |

| Fibroblast growth factor signaling | 2.55E-01 | AKT2 |

| Neuregulin signaling | 2.45E-01 | AKT2 |

| RANK signaling in osteoclasts | 2.45E-01 | AKT2 |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia signaling | 2.3E-01 | AKT2 |

| Stress-activated protein/Janus kinase signaling | 2.27E-01 | RAC2 |

| Glioma signaling | 2.24E-01 | AKT2 |

| Mouse embryonic stem cell pluripotency | 2.24E-01 | AKT2 |

| Insulin-like growth factor 1 signaling | 2.19E-01 | AKT2 |

| p53 signaling | 2.16E-01 | AKT2 |

| Neuropathic pain signaling in dorsal horn neurons | 2.11E-01 | PDIA3 |

| Cholecystokinin/gastrin-mediated signaling | 2.08E-01 | RHOA |

| Hepatocyte growth factor signaling | 1.98E-01 | AKT2 |

Abbreviations: ARP, actin-related protein; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T-cells; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; WASP, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein.

Table 3.

The 184 direct targets of DMXAA (5,6-dimethylxanthenone 4-acetic acid) in A549 cells analyzed by ingenuity pathway analysis

| Protein ID | Symbol | Entrez gene name | Location | Type(s) | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q5VXJ5 | SYCP1 | Synaptonemal complex protein 1 | Nucleus | Other | −27.155 |

| F8VVM2 | SLC25A3 | Solute carrier family 25 (mitochondrial carrier; phosphate carrier), member 3 | Cytoplasm | Transporter | −1.762 |

| B4DS13 | EIF4B | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4B | Cytoplasm | Translation regulator | −1.666 |

| E9PEU4 | ARCN1 | Archain 1 | Cytoplasm | Other | −1.523 |

| F5H3I4 | ACTR1A | ARP1 actin-related protein 1 homolog A (yeast) | Cytoplasm | Other | −1.513 |

| F5GY65 | SLC25A11 | Solute carrier family 25 (mitochondrial carrier; oxoglutarate carrier), member 11 | Cytoplasm | Transporter | −1.391 |

| F8VSA6 | NEDD8 | Neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally down-regulated 8 | Nucleus | Enzyme | −1.352 |

| B4DKS8 | HNRNPF | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein F | Nucleus | Other | −1.333 |

| F8WD96 | CTSD | Cathepsin D | Cytoplasm | Peptidase | −1.289 |

| F5GX11 | PSMA1 | Proteasome (prosome, macropain) subunit, α type, 1 | Cytoplasm | Peptidase | −1.286 |

| B4E1K7 | STOML2 | Stomatin (EPB72)-like 2 | Plasma membrane | Other | −1.276 |

| Q5TCU6 | TLN1 | Talin 1 | Plasma membrane | Other | −1.276 |

| F8W7P7 | WDHD1 | WD repeat and HMG-box DNA binding protein 1 | Nucleus | Other | −1.266 |

| E9PNH1 | GANAB | α-Glucosidase; neutral AB | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.250 |

| C9JW37 | PSMD14 | Proteasome (prosome, macropain) 26S subunit, non-ATPase, 14 | Cytoplasm | Peptidase | −1.250 |

| B4E241 | SRSF3 | Serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 3 | Nucleus | Other | −1.247 |

| E9PH29 | PRDX3 | Peroxiredoxin 3 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.245 |

| B7Z254 | PDIA6 | Protein disulfide isomerase family A, member 6 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.213 |

| B4DNJ5 | RPN1 | Ribophorin I | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.205 |

| D6RDN3 | CPLX2 | Complexin 2 | Cytoplasm | Other | −1.203 |

| E9PDQ8 | SUCLG2 | Succinate-CoA ligase, GDP-forming, β subunit | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.200 |

| F8W914 | RTN4 | Reticulon 4 | Cytoplasm | Other | −1.197 |

| F5H3T8 | RARS | Arginyl-tRNA synthetase | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.190 |

| B4E0X8 | FUBP1 | Far upstream element (FUSE) binding protein 1 | Nucleus | Transcription regulator | −1.187 |

| F8WF81 | DDB1 | Damage-specific DNA binding protein 1, 127 kDa | Nucleus | Other | −1.182 |

| B4DT43 | ETFA | Electron-transfer-flavoprotein, α polypeptide | Cytoplasm | Transporter | −1.171 |

| B4DRT4 | PEBP1 | Phosphatidylethanolamine binding protein 1 | Cytoplasm | Other | −1.171 |

| E9PPQ5 | CHORDC1 | Cysteine and histidine-rich domain (CHORD) containing 1 | Other | Other | −1.164 |

| D6RFI0 | SFXN1 | Sideroflexin 1 | Cytoplasm | Transporter | −1.161 |

| C9J1T2 | RHOA | Ras homolog family member A | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.157 |

| C9JPV1 | SLC6A6 | Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter), member 6 | Plasma membrane | Transporter | −1.150 |

| D6RFH4 | CYB5B | Cytochrome b5 type B (outer mitochondrial membrane) | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.143 |

| B4DQJ8 | PGD | Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.115 |

| B4E022 | TKT | Transketolase | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.104 |

| G3V5P4 | CFL2 | Cofilin 2 (muscle) | Extracellular space | Other | −1.103 |

| D6RF62 | PAICS | Phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxylase, phosphoribosylaminoimidazole succinocarboxamide synthetase | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.099 |

| B3KUK2 | SOD2 | Superoxide dismutase 2, mitochondrial | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.097 |

| D6REM6 | MATR3 | Matrin 3 | Nucleus | Other | −1.096 |

| B7Z2V6 | ATP6V1A | ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal 70 kDa, V1 subunit A | Plasma membrane | Transporter | −1.091 |

| B1AM77 | STOM | Stomatin | Plasma membrane | Other | −1.087 |

| D6RF44 | HNRNPD | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein D | Nucleus | Transcription regulator | −1.084 |

| B4E0R6 | IPO5 | Importin 5 | Nucleus | Transporter | −1.079 |

| Q5T8U3 | RPL7A | Ribosomal protein L7a | Cytoplasm | Other | −1.075 |

| A8K318 | PRKCSH | Protein kinase C substrate 80K-H | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.073 |

| C8KIM0 | GSR | Glutathione reductase | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.072 |

| G3V5Q1 | APEX1 | APEX nuclease (multifunctional DNA repair enzyme) 1 | Nucleus | Enzyme | −1.071 |

| A6NN01 | H2AFV | H2A histone family, member V | Nucleus | Other | −1.071 |

| B7Z6M1 | PLS3 | Plastin 3 | Cytoplasm | Other | −1.071 |

| B3KUB4 | CA12 | Carbonic anhydrase XII | Plasma membrane | Enzyme | −1.069 |

| F5GWY2 | ATIC | 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase/inosine 5′-monophosphate cyclohydrolase | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.068 |

| B4DIT7 | TGM2 | Transglutaminase 2 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.066 |

| E9PRQ6 | ACAT1 | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 1 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.065 |

| C9JPM4 | ARF4 | ADP-ribosylation factor 4 | Cytoplasm | Other | −1.059 |

| B1AH77 | RAC2 | Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 2 (rho family, small GTP binding protein Rac2) | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.053 |

| G3V3I1 | PSMA6 | Proteasome (prosome, macropain) subunit, α type, 6 | Cytoplasm | Peptidase | −1.049 |

| B4DVU3 | EIF3C | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3, subunit C | Other | Translation regulator | −1.047 |

| B4DKM5 | VDAC2 | Voltage-dependent anion channel 2 | Cytoplasm | Ion channel | −1.045 |

| B4DEM7 | CCT8 | Chaperonin containing TCP1, subunit 8 (theta) | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.044 |

| F5GX39 | TMED2 | Transmembrane emp24 domain trafficking protein 2 | Cytoplasm | Transporter | −1.043 |

| F5GZ27 | LONP1 | Lon peptidase 1, mitochondrial | Cytoplasm | Peptidase | −1.041 |

| F5H667 | ASPH | Aspartate β-hydroxylase | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.040 |

| C9JLU1 | POLR2H | Polymerase (RNA) II (DNA-directed) polypeptide H | Nucleus | Enzyme | −1.040 |

| B4DR70 | FUS | Fused in sarcoma | Nucleus | Transcription regulator | −1.039 |

| E7ETK5 | IMPDH2 | Inosine 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase 2 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.038 |

| B4DXW1 | ACTR3 | ARP3 actin-related protein 3 homolog (yeast) | Plasma membrane | Other | −1.037 |

| F8VNT9 | CD63 | CD63 molecule | Plasma membrane | Other | −1.036 |

| E9PKZ0 | RPL8 | Ribosomal protein L8 | Other | Other | −1.036 |

| B7Z6A4 | SURF4 | Surfeit 4 | Cytoplasm | Other | −1.036 |

| F5H1S2 | RPL13 | Ribosomal protein L13 | Cytoplasm | Other | −1.034 |

| B4DRF4 | PTPLAD1 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase-like A domain containing 1 | Cytoplasm | Other | −1.028 |

| B4DZP4 | DYNC1LI2 | Dynein, cytoplasmic 1, light intermediate chain 2 | Cytoplasm | Other | −1.024 |

| B3KQT9 | PDIA3 | Protein disulfide isomerase family A, member 3 | Cytoplasm | Peptidase | −1.024 |

| E5RJR5 | SKP1 | S-phase kinase-associated protein 1 | Nucleus | Transcription regulator | −1.024 |

| C9JV57 | BZW1 | Basic leucine zipper and W2 domains 1 | Cytoplasm | Translation regulator | −1.022 |

| B4DUR8 | CCT3 | Chaperonin containing TCP1, subunit 3 (γ) | Cytoplasm | Other | −1.022 |

| A8K3Z3 | PSMC5 | Proteasome (prosome, macropain) 26S subunit, ATPase, 5 | Nucleus | Transcription regulator | −1.022 |

| F5H8J3 | CLPTM1 | Cleft lip and palate associated transmembrane protein 1 | Plasma membrane | Other | −1.021 |

| B7Z4V2 | HSPA9 | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 9 (mortalin) | Cytoplasm | Other | −1.020 |

| F5GY50 | PTGR1 | Prostaglandin reductase 1 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.015 |

| B4DPJ8 | CCT6A | Chaperonin containing TCP1, subunit 6A (ζ 1) | Cytoplasm | Other | −1.014 |

| D6RG13 | RPS3A | Ribosomal protein S3A | Nucleus | Other | −1.013 |

| C9JTK6 | OLA1 | Obg-like ATPase 1 | Cytoplasm | Other | −1.011 |

| F8VRG3 | TWF1 | Twinfilin actin-binding protein 1 | Cytoplasm | Kinase | −1.007 |

| C9JZ20 | PHB | Prohibitin | Nucleus | Transcription regulator | −1.006 |

| C9JB50 | RPL28 | Ribosomal protein L28 | Cytoplasm | Other | −1.006 |

| B7Z795 | CES1 | Carboxylesterase 1 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.005 |

| F5GYN4 | OTUB1 | OTU deubiquitinase, ubiquitin aldehyde binding 1 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.005 |

| B7Z4T9 | CCT7 | Chaperonin containing TCP1, subunit 7 (eta) | Cytoplasm | Other | −1.004 |

| B4DGN5 | GLUD1 | Glutamate dehydrogenase 1 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | −1.004 |

| B4DDF7 | PPP2R1A | Protein phosphatase 2, regulatory subunit A, alpha | Cytoplasm | Phosphatase | 1.002 |

| B4DLR8 | NQO1 | NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, quinone 1 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | 1.005 |

| A6NLM8 | SSR4 | Signal sequence receptor, delta | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.008 |

| C9J7S3 | DARS | Aspartyl-tRNA synthetase | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | 1.009 |

| D6RAN4 | RPL9 | Ribosomal protein L9 | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.010 |

| B4E3C2 | RPL17 | Ribosomal protein L17 | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.012 |

| G3V279 | ERH | Enhancer of rudimentary homolog (Drosophila) | Nucleus | Other | 1.017 |

| B4DDG1 | UBE2L3 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2L 3 | Nucleus | Enzyme | 1.020 |

| C9JCK5 | PSMA2 | Proteasome (prosome, macropain) subunit, alpha type, 2 | Cytoplasm | Peptidase | 1.022 |

| E9PQD7 | RPS2 | Ribosomal protein S2 | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.023 |

| E7EX53 | RPL15 | Ribosomal protein L15 | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.024 |

| B7ZAT2 | CCT2 | Chaperonin containing TCP1, subunit 2 (β) | Cytoplasm | Kinase | 1.026 |

| E9PCY7 | HNRNPH1 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H1 (H) | Nucleus | Other | 1.026 |

| B8ZZQ6 | PTMA | α-prothymosin | Nucleus | Other | 1.027 |

| B4E335 | ACTB | β-actin | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.029 |

| A6NL93 | HMGN1 | High mobility group nucleosome binding domain 1 | Nucleus | Transcription regulator | 1.029 |

| Q5JR95 | RPS8 | Ribosomal protein S8 | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.031 |

| C9J9K3 | RPSA | Ribosomal protein SA | Cytoplasm | Translation regulator | 1.031 |

| C9JF49 | XPO1 | Exportin 1 | Nucleus | Transporter | 1.033 |

| E9PGI8 | CMPK1 | Cytidine monophosphate (UMP-CMP) kinase 1, cytosolic | Nucleus | Kinase | 1.034 |

| E9PMD7 | PPP1CA | Protein phosphatase 1, catalytic subunit, alpha isozyme | Cytoplasm | Phosphatase | 1.035 |

| G3V3T3 | ACIN1 | Apoptotic chromatin condensation inducer 1 | Nucleus | Enzyme | 1.038 |

| B1ALW1 | TXN | Thioredoxin | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | 1.040 |

| A8MUD9 | RPL7 | Ribosomal protein L7 | Nucleus | Transcription regulator | 1.041 |

| Q2YDB7 | PPIF | Peptidylprolyl isomerase F | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | 1.042 |

| B7Z9L0 | CCT4 | Chaperonin containing TCP1, subunit 4 (δ) | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.045 |

| E7EQR4 | EZR | Ezrin | Plasma membrane | Other | 1.046 |

| F8W118 | NAP1L1 | Nucleosome assembly protein 1-like 1 | Nucleus | Other | 1.051 |

| F8VZJ2 | NACA | Nascent polypeptide-associated complex α subunit | Cytoplasm | Transcription regulator | 1.055 |

| G3V5B3 | ERO1L | ERO1-like (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | 1.058 |

| B4E2S7 | LAMP2 | Lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 | Plasma membrane | Enzyme | 1.060 |

| B4DR63 | PSMC1 | Proteasome (prosome, macropain) 26S subunit, ATPase, 1 | Nucleus | Peptidase | 1.060 |

| G3V5M3 | DLST | Dihydrolipoamide S-succinyltransferase | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | 1.061 |

| C9JU56 | RPL31 | Ribosomal protein L31 | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.061 |

| B7Z1N6 | ALDOC | Aldolase C, fructose-bisphosphate | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | 1.062 |

| F8VWC5 | RPL18 | Ribosomal protein L18 | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.064 |

| C9JD32 | RPL23 | Ribosomal protein L23 | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.066 |

| A4D177 | CBX3 | Chromobox homolog 3 | Nucleus | Transcription regulator | 1.068 |

| Q5HYE7 | CRYZ | ζ-Crystallin, (quinone reductase) | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | 1.069 |

| B4E3E8 | DDX3X | DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box helicase 3, X-linked | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | 1.072 |

| A8K8G0 | HDGF | Hepatoma-derived growth factor | Extracellular space | Growth factor | 1.074 |

| F5H897 | TRAP1 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated protein 1 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | 1.074 |

| E9PNR9 | PRMT1 | Protein arginine methyltransferase 1 | Nucleus | Enzyme | 1.075 |

| E9PJH8 | SERPINH1 | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade H (heat shock protein 47), member 1 | Extracellular space | Other | 1.075 |

| C9JKI3 | CAV1 | Caveolin 1, caveolae protein, 22 kDa | Plasma membrane | Transmembrane receptor | 1.078 |

| D6R9P3 | HNRNPAB | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A/B | Nucleus | Enzyme | 1.081 |

| Q8N1C0 | CTNNA1 | Catenin (cadherin-associated protein), α1, 102 kDa | Plasma membrane | Other | 1.084 |

| B4DY66 | SAE1 | SUMO1 activating enzyme subunit 1 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | 1.087 |

| F6RFD5 | DSTN | Destrin (actin depolymerizing factor) | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.088 |

| C9J712 | PFN2 | Profilin 2 | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.088 |

| F5H4D6 | G3BP1 | GTPase activating protein (SH3 domain) binding protein 1 | Nucleus | Enzyme | 1.091 |

| B4DR31 | DPYSL2 | Dihydropyrimidinase-like 2 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | 1.092 |

| B6EAT9 | CD44 | CD44 molecule (Indian blood group) | Plasma membrane | Enzyme | 1.097 |

| B4E3S0 | CORO1C | Coronin, actin binding protein, 1C | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.108 |

| C9JHS6 | AKT2 | V-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 2 | Cytoplasm | Kinase | 1.116 |

| Q5TA01 | GSTO1 | Glutathione S-transferase ω1 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | 1.119 |

| F8W7C6 | RPL10 | Ribosomal protein L10 | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.124 |

| F5H0T1 | STIP1 | Stress-induced phosphoprotein 1 | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.127 |

| C9JFR7 | CYCS | Cytochrome c, somatic | Cytoplasm | Transporter | 1.128 |

| E7EPB3 | RPL14 | Ribosomal protein L14 | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.129 |

| F5H6Q2 | UBC | Ubiquitin C | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | 1.131 |

| B4DP24 | ELOVL1 | ELOVL fatty acid elongase 1 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | 1.135 |

| B3KS31 | TUBB6 | Tubulin, β6 class V | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.136 |

| B7Z9C4 | CTPS1 | CTP synthase 1 | Nucleus | Enzyme | 1.144 |

| F8W0G4 | PCBP2 | Poly(rC) binding protein 2 | Nucleus | Other | 1.146 |

| F8WBE5 | TFRC | Transferrin receptor | Plasma membrane | Transporter | 1.147 |

| B7Z2S5 | TXNRD1 | Thioredoxin reductase 1 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | 1.153 |

| B2RDM2 | TXNDC5 | Thioredoxin domain containing 5 (endoplasmic reticulum) | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | 1.154 |

| B4DSC0 | TNPO1 | Transportin 1 | Nucleus | Transporter | 1.155 |

| F8VPF3 | MYL6 | Myosin, light chain 6, alkali, smooth muscle and non-muscle | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.156 |

| B0V3J0 | TSEN34 | TSEN34 tRNA splicing endonuclease subunit | Nucleus | Enzyme | 1.159 |

| F8VR50 | ARPC3 | Actin related protein 2/3 complex, subunit 3, 21 kDa | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.162 |

| B3KTM6 | RPL5 | Ribosomal protein L5 | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.165 |

| Q5H907 | MAGED2 | Melanoma antigen family D, 2 | Plasma membrane | Other | 1.168 |

| Q75MH1 | RPS26 | Ribosomal protein S26 | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.181 |

| B4DZI8 | COPB2 | Coatomer protein complex, subunit beta 2 (β prime) | Cytoplasm | Transporter | 1.182 |

| Q5T4L4 | RPS27 | Ribosomal protein S27 | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.183 |

| Q5T093 | RER1 | Retention in endoplasmic reticulum sorting receptor 1 | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.188 |

| Q5VU59 | TPM3 | Tropomyosin 3 | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.198 |

| Q5T7C4 | HMGB1 | High mobility group box 1 | Nucleus | Other | 1.216 |

| C9JFK9 | BAG3 | Bcl2-associated athanogene 3 | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.219 |

| G3V153 | CAPRIN1 | Cell cycle associated protein 1 | Plasma membrane | Other | 1.223 |

| E5RHS5 | EIF3E | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3, subunit E | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.228 |

| B7Z8D3 | PSME3 | Proteasome (prosome, macropain) activator subunit 3 (PA28 γ; Ki) | Cytoplasm | Peptidase | 1.242 |

| B4E2Z3 | SLC3A2 | Solute carrier family 3 (amino acid transporter heavy chain), member 2 | Plasma membrane | Transporter | 1.247 |

| E9PP21 | CSRP1 | Cysteine and glycine-rich protein 1 | Nucleus | Other | 1.250 |

| B4DMT5 | EIF3F | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3, subunit F | Cytoplasm | Translation regulator | 1.263 |

| C9K0U8 | SSBP1 | Single-stranded DNA binding protein 1, mitochondrial | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.271 |

| A8MUB1 | TUBA4A | α-tubulin, 4a | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.298 |

| C9IZ41 | ZYX | Zyxin | Plasma membrane | Other | 1.326 |

| F5H4W0 | ME1 | Malic enzyme 1, NADP+-dependent, cytosolic | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | 1.331 |

| B4DPJ6 | TPD52L2 | Tumor protein D52-like 2 | Cytoplasm | Other | 1.340 |

| F5H0C8 | ENO2 | γ-enolase 2 (neuronal) | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | 1.347 |

| C9JL85 | MTPN | Myotrophin | Nucleus | Transcription regulator | 1.514 |

| B4DP11 | PTGES3 | Prostaglandin E synthase 3 (cytosolic) | Cytoplasm | Enzyme | 1.801 |

DMXAA modulates networked signaling pathways in A549 cells

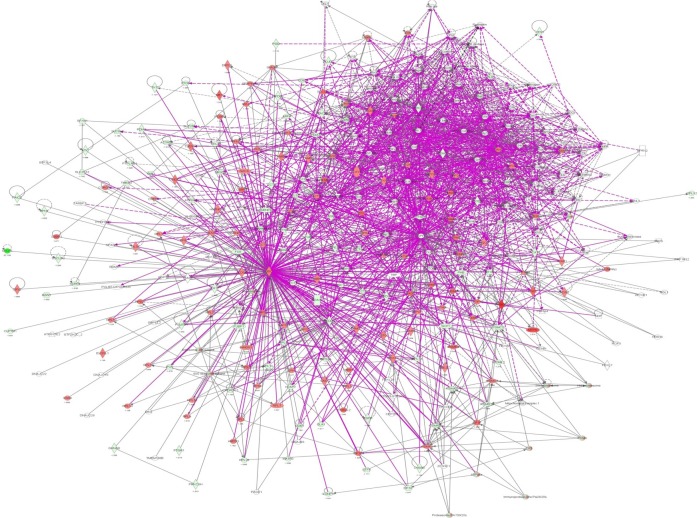

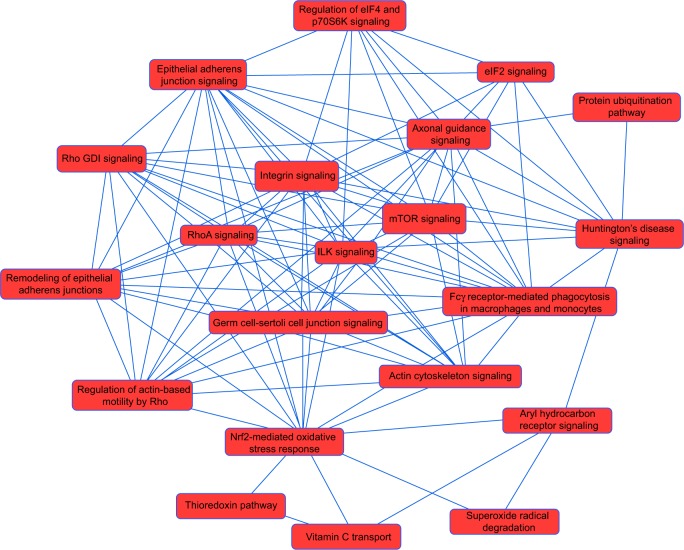

As seen in Figures 2 and 3, DMXAA showed an ability to regulate a number of networked signaling pathways that have critical roles in the regulation of cellular processes. IPA classified the top ten networks of signaling pathways responding to DMXAA in A549 cells (Table 4). These signaling networks have important roles in pathophysiological functions and the development of many important diseases. They included gene expression, DNA replication, recombination and repair, protein synthesis, small molecule biochemistry, carbohydrate metabolism, lipid metabolism, energy production, cellular response to therapeutics, connective tissue development and function, cellular assembly and organization, cellular compromise, cell morphology, free radical scavenging, cell death and survival, neurological disease, skeletal and muscular disorders, cardiac damage, cardiac fibrosis, development and function of cardiovascular system, and development of cancer.

Figure 2.

Proteomic analysis revealed the molecular interactome regulated by DMXAA in A549 cells.

Notes: A549 cells were treated with DMXAA 10 μM for 24 hours and the protein samples were subjected to quantitative SILAC-based proteomic analysis. There were 588 protein molecules regulated by DMXAA in A549 cells, with 281 protein molecules being increased and 306 protein molecules being decreased. Red indicates upregulation; green indicates downregulation; brown indicates predicted activation, and blue indicates predicted inhibition. The intensity of green and red molecule colors indicates the degree of downregulation and upregulation, respectively. The solid arrow indicates direct interaction and the dashed arrow indicates indirect interaction.

Abbreviations: DMXAA, 5,6-dimethylxanthenone 4-acetic acid; SILAC, stable-isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture.

Figure 3.

Proteomic analysis revealed a network of signaling pathways regulated by DMXAA in A549 cells.

Note: The network of signaling pathways was analyzed by ingenuity pathway analysis according to the 588 protein molecules regulated by DMXAA in A549 cells.

Abbreviation: DMXAA, 5,6-dimethylxanthenone 4-acetic acid; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; ILK, integrin-linked kinase; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; eIF, eukaryotic initiation factor; S6K, p70S6 kinase.

Table 4.

Networks of potential molecular targets regulated by DMXAA (5,6-dimethylxanthenone 4-acetic acid) in A549 cells

| ID | Molecules in network | Score | Focus molecules | Top diseases and functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ASPH, ATIC, BZW1, CHORDC1, CLPTM1, CMPK1, CRYZ, CYB5B, DYNC1LI2, ELOVL1, GANAB, H2AFV, ME1, OLA1, PAICS, PDIA6, PGD, PRKCSH, PTGR1, RER1, SAE1, SFXN1, SLC25A3, SLC25A11, SLC6A6, SSBP1, STOM, SUCLG2, SURF4, SYCP1, TMED2, TPD52L2, TSEN34, TXNDC5, UBC | 77 | 35 | Carbohydrate metabolism, small molecule biochemistry, lipid metabolism |

| 2 | 60S ribosomal subunit, ACIN1, Akt, CD63, DDX3X, EIF3, EIF3C, EIF3E, EIF3F, EIF4B, histone H1, HNRNPF, β-importin, IPO5, MTORC2, NEDD8, Rar, RPL5, RPL7, RPL9, RPL10, RPL13, RPL14, RPL15, RPL17, RPL18, RPL23, RPL28, RPL31, RPL7A, SLC3A2, thymidine kinase, TNPO1, TPM3, TRAP1 | 52 | 27 | Gene expression, protein synthesis, cancer |

| 3 | APEX1, ARF4, ARPC3, collagen type I, cytochrome C, ERK, ETFA, HDGF, HISTONE, HMGB1, HMGN1, HNRNPD, Hsp27, mitochondrial complex 1, NACA, NAP1L1, PHB, PLS3, PP2A, PPP2R1A, PRDX3, PRMT1, PTMA, ribosomal 40s subunit, RNR, RPS2, RPS8, RPS26, RPS27, RPS3A, RPSA, STOML2, TCF, VDAC2, XPO1 | 47 | 25 | Cellular response to therapeutics, connective tissue development and function, carbohydrate metabolism |

| 4 | 19S proteasome, 20s proteasome, 26s proteasome, α-tubulin, ATPase, BAG3, β-tubulin, CCT2, CCT3, CCT4, CCT7, CCT8, CCT6A, FUBP1, GSR, IκB, immunoproteasome Pa28/20s, LAMP2, LONP1, MTPN, NF-κB (complex), NQO1, PEBP1, proteasome PA700/20s, PSMA, PSMA1, PSMA2, PSMA6, PSMC1, PSMC5, PSMD14, PSME3, PTPLAD1, TUBB6, ubiquitin | 41 | 23 | Cell death and survival, DNA replication, recombination, and repair, energy production |

| 5 | ACTB, actin, ACTR1A, α-actinin, CAPRIN1, CFL2, cofilin, DARS, DLST, DPYSL2, DSTN, ERK1/2, Erm, EZR, F-actin, gilamin, G-actin, G3BP1, GLUD1, Na+, K+-ATPase, PCBP2, PFN2, PKG, profilin, proinsulin, Rho GDI, Rock, RPL8, RTN4, SRSF3, thioredoxin reductase, TLN1, TWF1, TXNRD1, ZYX | 34 | 20 | Cellular assembly and organization, cellular compromise, cellular function and maintenance |

| 6 | ALDOC, ATP6V1A, ATP6V1E2, BIN3, BTF3L4, CORO1C, DDB1, DNAJB3, DNAJC16, DNAJC22, DNAJC28, ERH, GRPEL2, GTF2H2C_2, HNRNPAB, HNRNPH1, HSPA9, MATR3, OTUB1, PAGE1, PCDHAC2, POLR2H, POLR2J2/POLR2J3, PPIF, RDM1, RPN1, SERPINH1, SPAG7, SSR4, STON1-GTF2A1L, TARBP1, TBP, TMEM106B, tubulin (complex), UBC | 25 | 16 | Gene expression, cell morphology, cellular assembly and organization |