Abstract

Background

Healthy children achieve better educational outcomes which, in turn, are associated with improved health later in life. The World Health Organization’s Health Promoting Schools (HPS) framework is a holistic approach to promoting health and educational attainment in school. The effectiveness of this approach has not yet been rigorously reviewed.

Methods

We searched 20 health, education and social science databases, and trials registries and relevant websites in 2011 and 2013.

We included cluster randomised controlled trials. Participants were children and young people aged four to 18 years attending schools/colleges. HPS interventions had to include the following three elements: input into the curriculum; changes to the school’s ethos or environment; and engagement with families and/or local communities.

Two reviewers identified relevant trials, extracted data and assessed risk of bias. We grouped studies according to the health topic(s) targeted. Where data permitted, we performed random-effects meta-analyses.

Results

We identified 67 eligible trials tackling a range of health issues. Few studies included any academic/attendance outcomes. We found positive average intervention effects for: body mass index (BMI), physical activity, physical fitness, fruit and vegetable intake, tobacco use, and being bullied. Intervention effects were generally small. On average across studies, we found little evidence of effectiveness for zBMI (BMI, standardized for age and gender), and no evidence for fat intake, alcohol use, drug use, mental health, violence and bullying others. It was not possible to meta-analyse data on other health outcomes due to lack of data. Methodological limitations were identified including reliance on self-reported data, lack of long-term follow-up, and high attrition rates.

Conclusion

This Cochrane review has found the WHO HPS framework is effective at improving some aspects of student health. The effects are small but potentially important at a population level.

Keywords: Child health, Adolescent health, Public health, Health promotion, Schools, Interventions, Systematic review

Background

This article is based on a Cochrane Review published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) 2014, Issue 4, DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD008958.pub2 (see www.thecochranelibrary.com for information). Cochrane Reviews are regularly updated as new evidence emerges and in response to feedback, and the CDSR should be consulted for the most recent version of the review.

Childhood and adolescence are profoundly important for public health. These years are key periods of biological and social change, laying the foundations for future adult health and economic well-being. The influence of childhood experiences on health later in life is well documented [1-6], with attitudes and behaviours acquired then ‘tracking’ into adulthood [7-9]. Establishing positive early childhood experiences in health and education has been highlighted by the World Health Organization (WHO) as key to reducing global health inequities [10]. As noted by Sawyer [11:1631] in a special issue of The Lancet on adolescent health, ‘many opportunities for prevention of non-communicable diseases, mental disorders, and injuries in adults arise from a focus on risk processes that begin in or before adolescence’. Promoting health during this early period of life is key to many public health agendas [11].

Given the significance of this period of the life course, schools are an important setting for health promotion, offering a comprehensive, sustained and efficient means of reaching this population. Because almost all children obtain some years of schooling, health promotion in schools can help reduce health inequities. Having a healthy, happy student body is also important for learning: healthy children achieve better educational outcomes which, in turn, are associated with improved health later in life [12].

The WHO’s Health Promoting Schools (HPS) framework, developed in the late 1980s, is underpinned by this reciprocal relationship between health and education. It seeks to overcome the limited success of traditional ‘health education’, establishing instead a holistic approach to promoting health in schools. Although definitions vary, the three key characteristics of a Health Promoting School are set out in Table 1.

Table 1.

The Health Promoting Schools framework

| School curriculum | Health education topics are promoted through the formal school curriculum. |

| Ethos and/or environment | Health and well-being of students are promoted through the ‘hidden’ or ‘informal’ curriculum, which encompasses the values and attitudes promoted within the school and the physical environment and setting of the school. |

| Families and/or communities | Schools seek to engage with families, outside agencies and the wider community in recognition of the importance of these other spheres of influence on children’s health. |

This approach has proved popular and has been implemented in numerous countries worldwide in the absence of clear evidence of its effectiveness or potential harms. A systematic review [13] conducted in 1999 suggested there were ‘limited but promising’ data that this approach could benefit student health. However, the conclusions of the review were limited by the small number of studies available, methodological weaknesses in the trials, and inclusion of non-randomised studies.

Focusing on studies with rigorous experimental evaluation designs, we sought to re-assess the current evidence of effectiveness of the HPS framework for improving the health and well-being of students and their academic achievement.

Methods

This paper is an abridged version of the associated Cochrane systematic review [14], where full details of the methods and results can be found. A protocol [15] for this review was published in The Cochrane Library and reporting of it adheres to PRISMA [16] guidelines.

Inclusion criteria

We included cluster randomised controlled trials (RCTs), with clusters at the level of school, district or other geographical area. Participants were students aged 4–18 years attending schools/colleges. To be eligible, interventions had to demonstrate active engagement in all three HPS domains listed in Table 1. Control schools offered no intervention or standard practice, or implemented an alternative intervention including only one or two of the HPS criteria. Primary and secondary outcomes of the review are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Review outcomes

| Primary health outcomes | Overweight/obesity; physical activity and sedentary behaviours; nutrition; tobacco use; alcohol use; substance use; sexual health; mental health; violence; bullying; infectious disease (e.g. diarrhoea, respiratory infections); safety and accident prevention; body image/eating disorders; sun safety; and oral health. |

| Primary educational outcomes | Academic achievement, including student standardised test scores or school-level academic achievement. |

| Secondary outcomes included | School attendance outcomes; other school-related outcomes (such as school climate or attachment to school). |

Search strategy

We searched the following databases and trials registries using broad and inclusive search terms to identify all eligible studies: ASSIA, Australian Education Index, British Education Index, BiblioMap, CAB Abstracts, Campbell Library, CENTRAL, CINAHL, Database of Educational Research, EMBASE, Education Resources Information Centre, Global Health Database, International Bibliography of Social Sciences, Index to Theses in Great Britain and Ireland, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe, Social Science Citation Index, Sociological abstracts, TRoPHI, clinicaltrials.gov, Current Controlled Trials, and International Clinical Trials Registry Platform. We also searched relevant websites and reference lists of relevant articles. Searches were conducted in 2011 and 2013. No date or language restrictions were applied.

One author performed an initial title screen, with a second author screening a randomly-selected 10% of titles for quality assurance purposes (kappa score = 0.88). Thereafter, two reviewers independently screened abstracts and full texts to determine eligibility.

Data extraction

For each study, two authors independently extracted data on participant and intervention characteristics and outcome measures. Where data were missing, we contacted study investigators.

We assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane tool [17]. Two authors independently assessed each study for potential selection, performance, detection, attrition, reporting or other biases.

For analysis, we grouped HPS interventions according to the health topic(s) targeted. For example, we distinguished between studies that sought to tackle obesity by targeting physical activity, those targeting nutrition and those targeting both together. We also identified multiple risk behaviour interventions which targeted multiple health outcomes with one intervention.

Statistical analysis

For dichotomous data, we used odds ratios to summarise study results. Continuous outcomes were summarised using a mean difference or standardised mean difference (SMD) when outcomes were reported on different scales. Where studies had not adjusted for clustering, we obtained intra-cluster correlation coefficients (ICCs) and mean cluster size from study investigators, allowing us to adjust standard errors for clustering prior to incorporation in meta-analyses. If unavailable, standard deviations (SDs) and ICCs were imputed based on similar studies.

Results were pooled within outcome and intervention types using random-effects meta-analyses where sufficient data were available. We quantified heterogeneity using τ (the between-study SD in effect sizes) and I2 [18]. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses were performed, as described in the full report [14].

Results

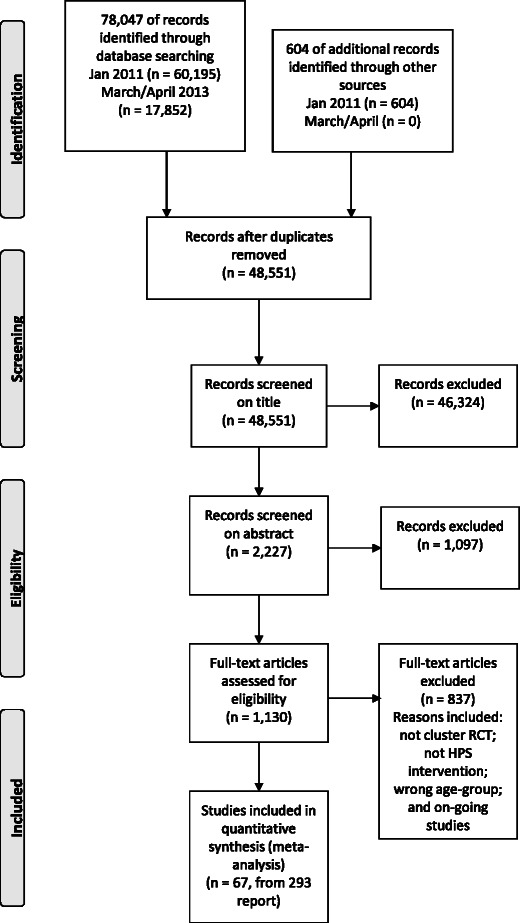

Searches yielded 48 551 records, from which we identified 67 eligible studies (Figure 1). Summary details of the types of interventions are presented in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection process.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the trials included in the review, by intervention focus

| Authors | Name | Review outcomes | Country | Target group | Duration for study design | Theory |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrition Interventions | ||||||

| Anderson 2005 [19] | - | Nutrition | UK | 6-7 and 10–11 year- olds | 8 months | Health Promoting Schools framework |

| Bere 2006 [20] | Fruits and Vegetables Make the Mark | Nutrition | Norway | Grade 6 | 6 months | Social cognitive theory |

| Evans 2013 [21] | Project Tomato | Nutrition | UK | Year 2 | 10 months | Framework for health maintenance behaviour |

| Foster 2008 [22] | School Nutrition Policy Initiative | Obesity/overweight, Nutrition | USA | Grades 4-6 | 2 years | None stated |

| Hoffman 2010 [23] | Athletes in Service, Fruit and Vegetable Promotion Program | Nutrition | USA | Kindergarten and Grade 1 | 2.5 years | Social learning theory |

| Hoppu 2010 [24] | - | Nutrition | Finland | Grade 8 | 8 months | Social cognitive theory |

| Lytle 2004 [25] | TEENS | Nutrition | USA | Grades 7-8 | 2 years | Social cognitive theory |

| Nicklas 1998 [26] | Gimme 5 | Nutrition | USA | Grade 9 | 3 years | PRECEDE Model of Health Education |

| Perry 1998 [27] | 5 A DAY Power Plus | Nutrition | USA | Grades 4-5 | 6 months | Social learning theory |

| Radcliffe 2005 [28] | - | Nutrition | Australia | Grade 7 | 11 months | Health Promoting Schools framework |

| Reynolds 2000 [29] | High 5 | Nutrition | USA | Grade 4 | 1 year | Social cognitive theory |

| Te Velde 2008 [30] | Pro Children Study | Nutrition | Netherlands, Norway, Spain | Grades 5-6 | 2 years | Social cognitive theory, Ecological model |

| Physical Activity Interventions | ||||||

| Eather 2013 [31] | Fit-4-Fun | Obesity/overweight, Physical Activity | Australia | Grades 5-6 | 8 weeks | Health Promoting Schools framework, Social cognitive Theory, Harter’s Competence Motivation Theory |

| Kriemler 2010 [32] | KISS | Obesity/overweight, Physical Activity | Switzerland | Grades 1 and 5 | 11 months | None stated |

| Simon 2006 [33] | ICAPS | Obesity/overweight, Physical Activity | France | Grade 6 | 4 years | “Theory based” but no details of a named theory provided |

| Wen 2008 [34] | - | Physical Activity | Australia | Years 4-5 | 2 years | Health Promoting Schools framework |

| Physical Activity + Nutrition Interventions | ||||||

| Arbeit 1992 [35] | Heart Smart | Obesity/overweight, Physical Activity, Nutrition | USA | Grades 4-5 | 2.5 years | Social cognitive theory |

| Brandstetter 2012 [36] | URMEL ICE | Obesity/overweight, Physical Activity, Nutrition | Germany | Grade 2 | 9 months | Social cognitive theory |

| Caballero 2003 [37] | Pathways | Physical Activity, Nutrition | USA | Grade 3 | 3 years | Social learning theory |

| Colín-Ramírez 2010 [38] | RESCATE | Obesity/overweight, Physical Activity, Nutrition | Mexico | Grades 4-5 | 1 year | None stated |

| Crespo 2012 [39] | Aventuras para Niños | Obesity/overweight, Physical Activity, Nutrition | USA | Kindergarten-Grade 2 | 5 semesters | Social ecological theory, Social cognitive theory, Health belief model, structural model of health behavior |

| Foster 2010 [40] | HEALTHY | Obesity/overweight | USA | Grades 6-8 | 3 years | None stated |

| Grydeland 2013 [41] | Health in Adolescents (HEIA) | Obesity/overweight, Physical Activity, Nutrition | Norway | Grade 6 | 20 months | Socio-ecological framework |

| Haerens 2006 [42] | - | Obesity/overweight, Physical Activity | Belgium | Grades 7-8 | 2 years | Theory of planned behaviour, Transtheoretical model, Social cognitive theory, Attitude, social influence and self-efficacy (ASE) model |

| Jansen 2011 [43] | Lekker Fit | Obesity/overweight, Physical Activity | Netherlands | Grades 3-8 | 8 months | Theory of planned behaviour, Ecological model |

| Llargues 2011 [44] | AVall | Obesity/overweight, Physical Activity, Nutrition | Spain | 5-6 year olds | 2 years | Educational methodology ‘IVAC’ |

| Luepker 1996 [45] | CATCH | Physical Activity, Nutrition | USA | Grade 3 | 3 years | Social cognitive theory, Social learning theory |

| Rush 2012 [46] | Project Energize | Obesity/overweight | New Zealand | 5 and 10 year olds | 2 years | Health Promoting Schools framework |

| Sahota 2001 [47] | APPLES | Obesity/overweight, Physical Activity, Nutrition | UK | Years 4-5 | 10 months | Health Promoting Schools framework |

| Sallis 2003 [48] | M-SPAN | Physical Acivity, Nutrition | USA | Grades 6-8 | 2 years | Ecological model |

| Shamah Levy 2012 [49] | Nutrición en Movimiento | Obesity/overweight, Nutrition | Mexico | Grade 5 | 6 months | Not explicitly theory-based, but mentions use of theory of peer learning for one element of the intervention (puppet theatre) |

| Trevino 2004 [50] | Bienestar (1) | Physical Activity, Nutrition | USA | Grade 4 | 5 months | Social cognitive theory, Social ecological theory |

| Trevino 2005 [51] | Bienestar (2) | Obesity/overweight, Physical Activity | USA | Grade 4 | 8 months | Social cognitive theory |

| Williamson 2012 [52] | Louisiana (LA) HEALTH | Obesity/overweight, Physical Activity, Nutrition | USA | Grades 4-6 | 2.5 years | Social learning theory |

| Tobacco Interventions | ||||||

| De Vries (Denmark) 2003 [53] | ESFA (Denmark) | Tobacco | Denmark | Grade 7 | 3 years | Attitude, social influence and self-efficacy (ASE) model |

| De Vries (Finland) 2003 [53] | ESFA (Finland) | Tobacco | Finland | Grade 7 | 3 years | Attitude, social influence and self-efficacy (ASE) model |

| Hamilton 2005 [54] | - | Tobacco | Australia | Grade 9 | 2 years | Health Promoting Schools framework |

| Perry 2009 [55] | Project MYTRI | Tobacco | India | Grades 6-8 | 2 years | Social cognitive theory, social influences model |

| Wen 2010 [56] | - | Tobacco | China | Grades 7-8 | 2 years | Socio-ecological framework, PRECEDE-PROCEED model |

| Alcohol Interventions | ||||||

| Komro 2008 [57] | Project Northland (Chicago) | Alcohol, Tobacco, Drugs | USA | Grade 6-8 | 3 years | Theory of triadic influence |

| Perry 1996 [58] | Project Northland (Minnesota) | Alcohol, Tobacco, Drugs | USA | Grades 6-8 | 3 years | Social learning theory |

| Multiple Risk Behaviour Interventions | ||||||

| Beets 2009 [59] | Positive Action (Hawai’i) | Tobacco, alcohol, drugs, violence, sexual health, academic and school-related outcomes | USA | Grades 2-3 | 3 years | Theory of self-concept, Theory of triadic influence |

| Eddy 2003 [60] | LIFT | Tobacco, alcohol, drugs | USA | Grades 1 and 5 | 10 weeks | Coercion theory |

| Flay 2004 [61] | Aban Aya | Violence, drugs, sexual health | USA | Grade 5 | 4 years | Theory of triadic influence |

| Li 2011 [62] | Positive Action (Chicago) | Tobacco, alcohol, drugs, violence, academic and school-related outcomes | USA | Grade 3 | 6 years | Theory of self-concept, Theory of triadic influence |

| Perry 2003 [63] | DARE Plus | Tobacco, alcohol, drugs, violence | USA | Grade 7 | 2 years | Theory of triadic influence |

| Schofield 2003 [64] | Hunter Region Health Promoting Schools Program | Tobacco | Australia | Years 7-8 | 2 years | Health Promoting Schools framework Community Organization Theory |

| Simons-Morton 2005 [65] | Going Places | Tobacco, alcohol | USA | Grades 6-8 | 3 years | Social cognitive theory |

| Sexual health Interventions | ||||||

| Basen-Engquist 2001 [66] | Safer Choices | Sexual health | USA | Grade 9 | 2 years | Social cognitive theory, social influence theory and models of school change |

| Ross 2007 [67] | MEMA Kwa Vijana | Sexual health | Tanzania | Students aged 14+ years | 3 years | Social learning theory |

| Mental Health and Emotional Well-being Interventions | ||||||

| Bond 2004 [68] | Gatehouse Project | Mental health and emotional well-being, tobacco, drugs, bullying | Australia | Grade 8 | 3 years | Health Promoting schools framework, attachment theory |

| Sawyer 2010 [69] | beyondblue | Mental health and emotional well-being | Australia | Year 8 | 3 years | Health Promoting Schools framework |

| Violence Prevention Interventions | ||||||

| Orpinas 2000 [70] | Students for Peace | Violence | USA | Grades 6-8 | 3 semesters | Social cognitive theory |

| Wolfe 2009 [71] | Fourth R | Violence, sexual health | Canada | Grade 9 | 15 weeks | None stated |

| Anti-bullying Interventions | ||||||

| Cross 2011 [72] | Friendly Schools | Bullying | Australia | Grade 4 | 2 years | Health Promoting Schools framework, Social cognitive theory, Ecological theory, Social control theory, Health belief model, Problem behaviour theory |

| Cross 2012 [73] | Friendly Schools, Friendly Families | Bullying | Australia | Grades 2, 4 and 6 | 2 years | Health Promoting Schools framework |

| Fekkes 2006 [74] | - | Bullying | Netherlands | 9-12 year-olds | 2 years | No specific theory but based on Olweus bullying programme |

| Frey 2005 [75] | Steps to Respect | Bullying | USA | Grades 3-6 | 1 year | None stated |

| Kärnä 2011 [76] | KiVa (1) | Bullying | Finland | Grade 4-6 | 9 months | Social cognitive theory |

| Kärnä 2013 [77] | KiVa (2) | Bullying | Finland | Grade 1–3 and 7-9 | 9 months | Social cognitive theory |

| Stevens 2000 [78] | - | Bullying | Belgium | 10 to 16 year-olds | Not clear | Social learning theory |

| Hand-washing Interventions | ||||||

| Bowen 2007 [79] | - | Illness from infectious diseases | China | Grade 1 | 5 months | None stated |

| Talaat 2011 [80] | - | Illness from infectious diseases | Egypt | Grades 1–3 (for data collection, but all children in school targeted) | 12 weeks | None stated |

| Miscellaneous Interventions | ||||||

| Hall 2004 [81] | School Bicycle Safety Project/The Helmet Files | Safety/accidents | Australia | Grade 5 | 2 years | Health Promoting Schools framework |

| McVey 2004 [82] | Healthy Schools- Healthy Kids | Body image | Canada | Grade 6-7 | 8 months | Health Promoting Schools framework, Ecological approach |

| Olson 2007 [83] | SunSafe | Sun safety | USA | Grades 6-8 | 3 years | Social cognitive theory, Socio-ecological theory, Protection motivation theory |

| Tai 2009 [84] | - | Oral health | China | Grade 1 | 3 years | Health Promoting Schools framework |

BMI = Body Mass Index; zBMI = Body Mass Index, standardised for age and gender.

Twenty-nine studies were conducted in North America (27 USA [22,23,25-27,29,35,37,39,40,45,48,50-52,57-63,65,66,70,75,83], 2 in Canada [71,82]), 19 in Europe [19-21,24,30,32,33,36,41,42,44,47,53,74,76-78,85], 11 in Australasia [28,31,34,46,54,64,68,69,72,73,81] and eight in middle- or low-income countries (China [56,79,84], India [55], Mexico [38,49], Egypt [80] and Tanzania [67]). Thirty-four studies focused on physical activity and/or nutrition. Seven focused on bullying, five on tobacco and two each targeted alcohol, mental health, violence, sexual health, and hand-hygiene. Seven studies evaluated multiple risk behaviour interventions. The remaining four studies focused on accident prevention, eating disorders, sun protection and oral health.

The quality of evidence was variable, both between studies and across the different domains of potential bias [14]. Poor reporting hampered our ability to assess risk of bias, particularly regarding random sequence generation, where the majority of studies were assessed as being at unclear risk of bias. Because in most studies all clusters were randomly allocated simultaneously, we deemed these at low risk of allocation concealment bias. It was difficult to blind participants to the fact they were participating in an intervention. As the majority of outcomes were measured by self-report, these were deemed to be at high risk of performance and detection bias due to lack of blinding. Where objective measures were reported (e.g. BMI), eight studies reported assessors were blind to group allocation. We assessed 34 studies as being at high risk of attrition bias. Lack of published protocols hampered our ability to assess risk of selective reporting of outcome data. Twenty-nine studies were rated as at high risk of other bias, largely relating to the external validity of the trials.

Impact on health outcomes

Table 4 presents summary effect estimates from meta-analyses for each health outcome. Details of the effect for each study, forest plots for each analysis and subgroup and sensitivity analyses are presented in full in the Cochrane review [14].

Table 4.

Summary estimates (95% CIs) for health outcomes meta-analyses

| Outcome | Intervention focus | Number of studies | Intervention participants | Control participants | Mean difference | 95% CI | I 2 | τ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | Nutrition only | 1 | 479 | 364 | −0.04 | −0.28, 0.20 | n/a | n/a |

| Physical Activity only | 3 | 772 | 658 | −0.38 | −0.73, −0.03* | 86% | 0.08 | |

| Physical Activity & Nutrition | 9 | 6520 | 7108 | −0.11 | −0.24, 0.02 | 84% | 0.03 | |

| zBMI | Nutrition only | 1 | 479 | 364 | −0.01 | −0.09, 0.07 | n/a | n/a |

| Physical Activity only | 1 | 102 | 94 | −0.47 | −0.69, −0.25* | n/a | n/a | |

| Physical Activity & Nutrition | 7 | 5672 | 5512 | 0 | −0.04, 0.03 | 41% | 0 | |

| Standardised mean diff. | 95% CI | I 2 | Tau | |||||

| Physical Activity | Nutrition only | 1 | 416 | 335 | 0.02 | −0.02, 0.06 | n/a | n/a |

| Physical Activity only | 2 | 671 | 563 | 0.17 | −0.16, 0.50 | 93% | 0.05 | |

| Physical Activity & Nutrition | 6 | 3244 | 2946 | 0.14 | 0.03, 0.26* | 66% | 0.01 | |

| Physical Fitness | Physical Activity only | 2 | 396 | 298 | 0.35 | −0.20, 0.90 | 95% | 0.15 |

| Physical Activity & Nutrition | 3 | 2059 | 2171 | 0.12 | 0.04, 0.20* | 0% | 0 | |

| Fat intake | Nutrition only | 7 | 2205 | 2011 | −0.08 | −0.21, 0.05 | 68% | 0.02 |

| Physical Activity & Nutrition | 10 | 6498 | 5962 | −0.04 | −0.20, 0.12 | 95% | 0.06 | |

| Fruit & Vegetable intake | Nutrition only | 9 | 3293 | 2917 | 0.15 | 0.02, 0.29* | 83% | 0.03 |

| Physical Activity & Nutrition | 4 | 3507 | 3105 | 0.04 | −0.18, 0.26 | 79% | 0.04 | |

| Depression | Emotional well-being | 2 | 3252 | 2847 | 0.06 | −0.00, 0.13 | 0% | 0 |

| Anti-bullying | 1 | 1106 | 1118 | 0 | −0.08, 0.08 | n/a | n/a | |

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | I 2 | Tau | |||||

| Tobacco use | Tobacco only | 3 | 2244 | 2503 | 0.77 | 0.64, 0.93* | 16% | 0 |

| Multiple Risk Behaviour | 5 | 5503 | 4489 | 0.84 | 0.76, 0.93* | 0% | 0 | |

| Emotional well-being | 1 | 315 | 315 | 0.79 | 0.59, 1.06 | n/a | n/a | |

| Alcohol only | 1 | 1005 | 896 | 0.74 | 0.61, 0.90* | n/a | n/a | |

| Alcohol use | Alcohol only | 2 | 3506 | 3975 | 0.72 | 0.34, 1.52 | 82% | 0.25 |

| Multiple Risk Behaviour | 4 | 4496 | 3644 | 0.75 | 0.55, 1.02 | 78% | 0.07 | |

| Emotional well-being | 1 | 809 | 810 | 1.13 | 0.76, 1.67 | n/a | n/a | |

| Substance use | Multiple Risk Behaviour | 3 | 3804 | 3016 | 0.57 | 0.29, 1.14 | 71% | 0.26 |

| Alcohol only | 2 | 3506 | 3975 | 0.94 | 0.78, 1.12 | 0% | 0 | |

| Emotional well-being | 1 | 233 | 233 | 0.81 | 0.57, 1.15 | n/a | n/a | |

| Violence | Violence prevention | 1 | 929 | 1161 | 1.13 | 0.61, 2.07 | n/a | n/a |

| Multiple Risk Behaviour | 3 | 3806 | 3014 | 0.5 | 0.23, 1.09 | 93% | 0.42 | |

| Being bullied | Anti-bullying | 6 | 13993 | 12263 | 0.83 | 0.72, 0.96* | 61% | 0.02 |

| Multiple Risk Behaviour | 1 | 2635 | 2108 | 0.97 | 0.90, 1.05 | n/a | n/a | |

| Emotional well-being | 1 | 481 | 482 | 0.88 | 0.68, 1.13 | n/a | n/a | |

| Bullying others | Anti-bullying | 6 | 13949 | 12227 | 0.9 | 0.78, 1.04 | 67% | 0.02 |

| Multiple Risk Behaviour | 1 | 195 | 168 | 0.49 | 0.34, 0.71* | n/a | n/a | |

*95% confidence intervals do not include the null.

BMI = Body Mass Index; zBMI = Body Mass Index, standardised for age and gender.

BMI/zBMI

On average, Physical Activity interventions were able to reduce BMI in intervention students by 0.38 kg/m2 (95% CI 0.03 to 0.73), relative to control schools (Table 4). Although heterogeneity was large (I2 = 86%) all three studies gave evidence in favour of the intervention. Nine studies targeted Physical Activity + Nutrition and also showed an average reduction in BMI of 0.11 kg/m2 but with a wide confidence interval crossing the null (95% CI −0.24 to 0.02). The single nutrition intervention [22] measuring BMI did not show any impact.

When zBMI was used (which accounts for age and gender), only the single Physical Activity intervention [31] showed an effect (MD = 0.47, 95% CI −0.69 to −0.25). No effect was found for the Nutrition-only or the Physical Activity + Nutrition interventions.

Physical activity/fitness

On average, there was evidence that Physical Activity + Nutrition interventions produced a small increase in physical activity in students relative to controls (SMD = 0.14, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.26) but again, heterogeneity was high (I2 = 66%) (Table 4). The two Physical Activity interventions showed differing results with one favouring the intervention [33] and the other showing no effect [32]. No effect was seen for the single Nutrition-only intervention [22].

For physical fitness, there was evidence that Physical Activity + Nutrition interventions were effective at increasing fitness levels in students (SMD = 0.12, 95% CI 0.04, 0.20). The two Physical Activity interventions [31,32] also showed a positive estimated effect but with a large amount of heterogeneity (I2 = 95%) and a wide confidence interval crossing the null (SMD = 0.35, 95% CI −0.20, 0.90).

Nutrition

High levels of heterogeneity were observed for both fruit and vegetable intake, and fat intake outcomes. Nutrition-only interventions were effective on average in increasing reported fruit and vegetable intake among students (SMD = 0.15, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.29, I2 = 83%), but not for reducing fat intake. On average, Physical Activity + Nutrition interventions had no effect on fat intake or fruit and vegetable intake.

Tobacco

There was good evidence that both Tobacco-only (OR = 0 · 77, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.93, I2 = 16%) and Multiple Risk Behaviour (OR = 0 · 84, 95% CI 0.76 to 0.93, I2 = 0%) interventions are effective in reducing smoking (Table 4). The alcohol intervention [58], which also looked at the impact on tobacco use, also showed a positive intervention effect (OR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.9). The single Emotional well-being intervention gave an estimated effect in favour of the intervention (OR = 0.79) but with a wide confidence interval (95% CI 0.59 to 1.06).

Alcohol

Although some individual studies showed an effect on reducing alcohol intake, on average there was no evidence of an effect (Table 4). The two Alcohol-only interventions produced conflicting results, with confidence intervals that do not overlap: one suggesting a positive effect of the intervention on alcohol intake [58] (OR = 0.45, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.87) and the other suggesting no effect [57] (OR = 0.99, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.01). The Multiple Risk Behaviour interventions similarly produced conflicting results, with the two Positive Action trials both indicating a positive effect (OR = 0.48, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.73 [59]; OR = 0.44, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.92 [62]) but the remaining two studies finding no effect. The Emotional well-being intervention similarly found no effect.

Drugs

Neither the Alcohol-only interventions [57,58] nor the Emotional well-being intervention [68] showed evidence of effectiveness in reducing substance use (Table 4). One Multiple Risk Behaviour intervention [59] found a positive effect on substance use (OR = 0.28, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.63) but the other two studies reported inconclusive results [62,63], so that the estimate of average effect had a wide confidence interval (OR = 0.57, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.14).

Mental health

There was no evidence that these interventions were effective in reducing depression (Table 4). Indeed, for the two studies focusing specifically on mental health and emotional well-being, estimated effect sizes were in the opposite direction with intervention students reporting slightly poorer mental health (OR = 0.06, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.13). The Anti-bullying intervention [74] found no effect on levels of depression in students.

Violence

There was no evidence that Violence Prevention or Multiple Risk Behaviour interventions were effective in reducing violent behaviour (Table 4). The Violence Prevention intervention [70] found no effect on student violence. The Multiple Risk Behaviour interventions produced conflicting results. The two Positive Action trials both found evidence of a reduction in violent behaviours (OR = 0.32, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.32 [59]; OR = 0.38, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.56 [62]). However, another much larger study [63] found no effect. The resulting pooled estimate from a random-effects meta-analysis had a very wide confidence interval (OR = 0.50, 95% CI 0.23 to 1.09).

Bullying

Anti-bullying interventions showed an average reduction of 17% for reports of being bullied (OR = 0.83, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.96, I2 = 61%) relative to controls, although there was considerable heterogeneity (Table 4). For bullying others, the confidence interval for the pooled effect crossed the null (OR = 0.90, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.04, I2 = 67%), but the two largest studies [76,77] investigating the same intervention showed strong evidence of an effect. The Emotional well-being intervention [68] failed to show impact on both being bullied or bullying others. No effect was seen for being bullied for the single Multiple Risk Behaviour intervention [63] reporting this outcome. However, another Multiple Risk Behaviour intervention [62] reported the effect of their intervention on bullying others and found evidence of a large reduction (OR = 0.49, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.71).

Other health outcomes

We were unable to meta-analyse results from studies for the following topics due to paucity of data: sexual health, hand-hygiene, accident prevention, eating disorders, sun safety and oral health. Results from these interventions are summarised in the Cochrane review [14].

Educational outcomes

Very few studies presented any academic or attendance outcomes. Two studies collected data on standardised scores for reading and maths [59,62]. They also presented data on suspensions and retentions in grades, student disaffection and teachers’ perceptions of student motivation and performance. Only four studies [59,62,79,80] presented student absenteeism data. Educational outcome results are summarised in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of impact on educational outcomes

| Study reference | Intervention type | Authors’ conclusions |

|---|---|---|

| Li 2011 [62] | Multiple Risk Behaviour | Positive intervention effects found for: student disaffection with learning (P < 0.01); teachers’ ratings of academic motivation (P < 0.05); absenteeism rates (P < 0.05) |

| No effect found for: teachers’ ratings of academic performance; standardised test scores for reading and maths | ||

| Beets 2009 [59] | Multiple Risk Behaviour | Positive intervention effects found for: standardised test scores for reading and maths (P = 0.043 and 0.006, respectively); absenteeism (P = 0.001); suspensions (P = 0.028); student, teacher and parent ‘School Quality Composite’ scores (P = 0.015, 0.006 and 0.007, respectively) |

| No effect found for: student retentions in grade | ||

| Fekkes 2006 [74] | Anti-bullying | No effect found for: general satisfaction with school life; satisfaction with contact with other pupils; or satisfaction with contact with teachers |

| Bond 2004 [68] | Mental health | Positive intervention effect found for: school attachment (Adj. OR 1.33, 95%CI 1.02 to 1.75; un-adjusted OR non-significant) |

| Sahota 2001 [47] | Physical Activity and Nutrition | No effect found for: self-perceived scholastic competence |

| Sawyer 2010 [69] | Mental health | Positive intervention effect found for: teacher ratings of school climate over time (intervention x time β = 0.43, P < 0.05) |

| No effect found for: student rating of school climate | ||

| Bowen 2007 [79] | Hand hygiene | Positive intervention effect found for: attendance. Intervention schools (expanded group) experienced 42% fewer absence episodes (P = .03) and 54% fewer days of absence (P = .03) than control schools |

| Talaat 2011 [80] | Hand hygiene | Positive intervention effect found for: attendance. Overall, absences caused by illness were reduced by 21% in intervention schools (5.7 vs. 7.2 median episodes, P < 0.001) |

| Simons-Morton 2005 [65] | Multiple Risk Behaviour | No effect found for: students’ perceptions of school climate |

| McVey 2004 [82] | Eating disorders | No effect found for: teachers’ perceptions of school climate |

| Kärnä 2011 [76] | Anti-bullying | Positive intervention effect found for: well-being at school in intervention students (0.096, P = 0.011) |

Discussion

This is the first systematic review of cluster RCTs to assess the effectiveness of the WHO’s Health Promoting Schools framework in improving health and academic achievement in students. We identified 67 eligible studies focusing on a wide range of health issues.

Our analyses showed modest positive intervention effects on average in reducing BMI, smoking and incidence of being bullied, and increasing physical activity, fitness, and fruit and vegetable intake. We found little or no evidence of effect for HPS interventions assessing zBMI, fat intake, alcohol use, drug use, violence, depression or bullying others. Paucity of data meant we were unable to meta-analyse data for outcomes relating to sexual health, hand-washing, oral health, accident prevention or eating disorders.

HPS interventions focusing on physical activity alone found an average reduction in BMI of 0.38 kg/m2 but no effect was found for Physical Activity + Nutrition interventions. We found little evidence of effect for zBMI, other than in the single Physical Activity intervention [31]. Physical Activity + Nutrition interventions were, on average, able to produce increases in physical activity and fitness, equivalent to an additional three minutes of moderate-to-vigorous activity per day and a 0.25 level increase in the shuttle run fitness test. Those interventions focused solely on nutrition increased fruit and vegetable intake by an average of 30 g/day or roughly half a portion. These effect sizes are small but are comparable to findings from other school based interventions [86-88]. Small effects scaled up to population level can produce public health benefits [89], although at present these potential gains appear modest. Stronger evidence is available for HPS effects on smoking and bullying. Students receiving HPS interventions were, on average, 23% less likely to smoke and 17% less likely to be bullied.

We found little or no evidence of effect for alcohol use, drug use, violence, depression and bullying others but this should not be confused with ‘evidence of no effect’. For the majority of outcomes, data were available from few studies. Although the confidence intervals for the pooled effect cross the null, for all but one outcome (depression), summary estimates from meta-analyses consistently favour the HPS intervention. Thus, while we cannot at this stage conclude that the HPS approach is effective for these outcomes, there is sufficient evidence of promise to warrant further trials in these areas. Indeed, interventions focusing specifically on school environments have shown promising effects in reducing alcohol use and violence in students [90]. That some individual trials showed evidence of effect for several of these outcomes also suggests the need for exploration into which intervention components might be effective.

The use of cluster RCTs to evaluate complex interventions such as the HPS framework is much debated. Some have argued that RCTs are an inappropriate method to evaluate complex public health programmes, based on an assumption that RCTs require highly standardised intervention components and methods of delivery that preclude the possibility of local adaptation [91,92]. This assumption is unfounded [93,94]. Well-designed cluster RCTS can capture complexity and allow for local adaptation; the critical issue is ‘what’ is standardised (the intervention components or the steps in the change process) [94]. This review of 67 cluster RCTs represents an important contribution to the body of evidence on the effectiveness of the HPS approach. Focusing on the most robust evidence available and using a conservative approach to assess effectiveness, we have found evidence in favour of the HPS framework for a number of important outcomes. To contextualise these findings, it is important this review be read alongside other evaluations of the HPS framework employing different evaluation study designs [95,96] which offer insight into the process and practicalities of implementation.

Our meta-analyses provide the best summary to-date of the likely average effect of HPS interventions. However this review presented methodological challenges. Unlike clinical trials which often involve standardised interventions, homogenous populations and well-established outcome measures, public health interventions display more heterogeneity, particularly in the case of non-prescriptive interventions such as the HPS framework that allows considerable flexibility in intervention components.

Our meta-analyses have limitations. First, where standard deviations (SD) for study populations were not reported, we imputed a SD from another similar study to calculate a standardised mean difference (SMD). Sensitivity analyses examined the impact of this decision on our analyses [14]. Second, to calculate SMDs we used the overall (‘total’) SD across all individuals in a study rather than the ‘within-cluster’ SD, as studies rarely reported the latter. However, because ICCs were found to be small, this is unlikely to have substantially affected our results. Finally, in a minority of studies we used ICCs from similar studies to adjust for clustering, conservatively choosing the largest available ICC.

A further limitation of the review is that we are unable to compare the effectiveness of the HPS approach to simpler, less holistic interventions because most studies compared HPS interventions against no intervention or the school’s usual practice. While HPS effect sizes are broadly similar to results from other school-based systematic reviews [86-88,97,98], the latter often include different types of interventions ranging from ‘curriculum only’ interventions to more comprehensive programmes making meaningful comparisons difficult. Future studies should consider use of factorial designs to identify the relative importance of the three HPS domains and the way in which they interact.

Whilst our review has found evidence in favour of the HPS approach for a number of outcomes, it has also identified gaps in our knowledge base. We lack sufficient data at present to determine the effect of this approach for a number of health outcomes, particularly mental health and sexual health. We also identified an imbalance between which health topics were focused on at different ages. Physical activity and/or nutrition interventions tended to focus on younger children (<12 years) while substance use, violence, sexual health and mental health interventions usually targeted older students (12–14 year-olds). This imbalance is unjustified. Obesity does not just affect younger children [99]; we need to develop effective obesity-prevention interventions for older children too. Equally, two of the most effective Multiple Risk Behaviour interventions [59,62] focusing on substance use and violence were conducted in elementary-school children, suggesting that intervening early may help prevent risk-taking in teenage years. We also identified the family/community domain to be the weakest aspect of the implementation of the HPS framework with most studies employing very minimal efforts to engage families (e.g. newsletter articles or flyers).

The majority of studies did not provide data on long-term follow-up or economic costs so the sustainability and cost-effectiveness of this approach is largely unknown. Studies were also often underpowered and relied heavily on self-reported data. It is disappointing to note that many of these methodological issues were identified in a previous review of the HPS framework and little improvement has been made in the past fifteen years [13]. Additionally, the current evidence base is predominantly based on studies from high-income contexts, mostly from North America. Only eight studies were conducted outside of high-income countries, and only one took place within a low-income country [67].

The lack of evidence from poorer parts of the world is worrying. Given the well-established links between poor nutrition and infectious disease on children’s cognitive development [100,101], the HPS framework should have much to offer in such contexts. Conversely, the tripling of obesity levels in just twenty years in low- and middle-income countries [102] demands cross-sectoral action, which the HPS framework might help address. Also, aggressive marketing of tobacco in the developing world has led to an increase in smoking, and any substantial increase in adolescent smoking in these contexts will have devastating consequences for future adult health [11:1636]. There are over three billion 0–24 year-olds alive today, almost 90% of whom live in low-and middle-income countries [103]. Investing in child and adolescent health in such contexts is crucial for improving population health and, consequently, national economic development.

Finally, our review highlights the lack of evidence regarding the educational impact of the HPS framework. Only four studies measured academic attainment or student attendance. This is disappointing for two reasons. First, it suggests researchers may have failed to grasp that improving educational outcomes is, in itself, a public health priority. Second, interventions are more likely to be successful and scaled up if educationalists are convinced it will contribute to the core mission of schools: to educate students. The WHO recently highlighted the lack of attention paid to the impact of child health on educational outcomes in high-income countries [12]. Future HPS evaluations should seek to address this gap.

Child and adolescent health matter. Investment in these formative years can prevent suffering, reduce inequity, create healthy and productive adults and deliver social and economic dividends to nations. Schools are an obvious place to facilitate this investment given the inextricable links between health and education [104]. Ultimately the aim of these two disciplines is largely the same: to create healthy, well-educated individuals who can contribute successfully to society.

Despite the obvious connections, across the globe structural barriers prevent the realisation of this mutual agenda. Government departments responsible for health and education often operate in isolation from one another and this fundamental connection is lost. The WHO explicitly set out a new vision of health and education in its HPS framework, yet since its inception there appears to have been little advance in breaking down this siloed approach. Our review demonstrates the potential benefits of this approach for some health outcomes but not others. We have yet to see its benefit for education. This is a political issue. Governments must commit to fostering the meaningful cross departmental working that would allow this policy to achieve its potential.

Conclusion

This review has found the WHO HPS framework is effective at improving some aspects of student health and shows evidence of promise in improving others. The effects are small but potentially important at a population level.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Professor Geraldine Macdonald and all at the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Group for their assistance in producing this review. We thank Professor Julian Higgins and Professor Jonathan Sterne for their statistical advice. We also acknowledge the assistance of Val Hamilton, Selman Mirza, Pandora Pound, Heide Busse, Jeff Brunton and the EPPI-Reviewer team in various aspects of the review process.

The work was undertaken with the support of The Centre for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions for Public Health Improvement (DECIPHer), a UKCRC Public Health Research Centre of Excellence. Joint funding (MR/KO232331/1) from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council, Medical Research Council, the Welsh Government and the Wellcome Trust, under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, is gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- ASSIA

Applied social sciences index and abstracts

- BMI

Body mass index

- CINAHL

Cumulative index to nursing and allied health literature

- HPS

Health promoting schools

- ICC

Intra-cluster correlation coefficients

- OR

Odds ratio

- PRISMA

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- RCT

Randomised controlled trial

- SD

Standard deviation

- SMD

Standardised mean difference

- TRoPHI

Trials register of promoting health interventions

- WHO

World health organization

Footnotes

Competing interests

KK was an investigator in three studies [57,58,63] included in the review and received royalties for the sale of these prevention curricula. She was not involved in the data extraction or interpretation of data from these studies for this review. EW has previously received funding to her institution and to herself from the World Health Organization for unrelated pieces of work. RL has undertaken consultancy work for the WHO as part of a Delphi exercise into mental health and psychosocial support in humanitarian settings. The WHO had no role in the study design, data extraction, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. RC is a Director of a not-for-profit company, DECIPHer IMPACT Ltd, set up to enable organisations to use the DECIPHer ASSIST smoking prevention programme – a peer-led intervention for use with adolescents in secondary schools. She received fees paid into a grant account held by the University of Bristol and used to support further research activities. All remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

RL wrote the protocol, performed the bibliographical searches, identified the studies, extracted data, planned the analyses and produced the first draft of the manuscript. RC was the Principal Investigator and had the original idea for the review, obtained funding for it and oversaw the review process. She was also involved in drafting the protocol, identifying studies, extracting data, and producing the final manuscript. TP extracted data, undertook the statistical analyses and assessed studies’ risk of bias. HJ provided statistical advice and guidance. DM, CB, SM, KK, LG and EW helped identify studies, extracted data, and provided input into the protocol and final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Rebecca Langford, Email: beki.langford@bristol.ac.uk.

Christopher Bonell, Email: c.bonell@ioe.ac.uk.

Hayley Jones, Email: hayley.jones@bristol.ac.uk.

Theodora Pouliou, Email: dora.pouliou@gmail.com.

Simon Murphy, Email: murphys7@Cardiff.ac.uk.

Elizabeth Waters, Email: ewaters@unimelb.edu.au.

Kelli Komro, Email: komro@ufl.edu.

Lisa Gibbs, Email: lgibbs@unimelb.edu.au.

Daniel Magnus, Email: drdanmagnus@gmail.com.

Rona Campbell, Email: rona.campbell@bristol.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–58. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galobardes B, Smith GD, Lynch JW. Systematic review of the influence of childhood socioeconomic circumstances on risk for cardiovascular disease in adulthood. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(2):91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO world mental health surveys. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(5):378–85. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poulton R, Caspi A, Milne BJ, Thomson WM, Taylor A, Sears MR, et al. Association between children’s experience of socioeconomic disadvantage and adult health: a life-course study. Lancet. 2002;360(9346):1640–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11602-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wadsworth MEJ, Kuh DJL. Childhood influences on adult health: a review of recent work from the British 1946 national birth cohort study, the MRC national survey of health and development. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1997;11(1):2–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.1997.d01-7.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright CM, Parker L, Lamont D, Craft A. Implications of childhood obesity for adult health: findings from thousand families cohort study. BMJ. 2001;323(7324):1280–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7324.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelder SH, Perry CL, Klepp KI, Lytle LL. Longitudinal tracking of adolescent smoking, physical activity, and food choice behaviors. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(7):1121–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.84.7.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JWR, Van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJM. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2008;9(5):474–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(13):869–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.CSDH . Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sawyer SM, Afifi RA, Bearinger LH, Blakemore S-J, Dick B, Ezeh AC, et al. Adolescence: a foundation for future health. Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1630–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suhrcke M, De Paz Nieves C. The Impact of Health and Health Behaviours on Educational Outcomes in High-Income Countries: A Review of the Evidence. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lister-Sharp D, Chapman S, Stewart-Brown S, Sowden A. Health promoting schools and health promotion in schools: two systematic reviews. Health Technol Assess. 1999;3(22):1–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langford R, Bonell C, Jones H, Pouliou T, Murphy S, Waters E, et al. The WHO Health Promoting School framework for improving the health and well-being of students and their academic achievement. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;4:CD008958. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008958.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langford R, Campbell R, Magnus D, Bonell C, Murphy S, Waters E, et al. The WHO Health Promoting School framework for improving the health and well-being of students and staff. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011;1:CD008958. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008958.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:B2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins J, Altman D. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgin J, Green JG, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins J, Thompson S, Deeks J, Altman D. Measuring inconsistency in meta-anlyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson AS, Porteous LEG, Foster E, Higgins C, Stead M, Hetherington M, et al. The impact of a school-based nutrition education intervention on dietary intake and cognitive and attitudinal variables relating to fruits and vegetables. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8(6):650–6. doi: 10.1079/PHN2004721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bere E, Veierod MB, Bjelland M, Klepp KI. Outcome and process evaluation of a Norwegian school-randomized fruit and vegetable intervention: fruits and vegetables make the marks (FVMM) Health Educ Res. 2006;21(2):258–67. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans CE, Ransley JK, Christian MS, Greenwood DC, Thomas JD, Cade JE. A cluster-randomised controlled trial of a school-based fruit and vegetable intervention: Project Tomato. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(6):1073–81. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012005290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foster GD, Sherman S, Borradaile KE, Grundy KM, Vander Veur SS, Nachmani J, et al. A policy-based school intervention to prevent overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):e794–802. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffman JA, Franko DL, Thompson DR, Power TJ, Stallings VA. Longitudinal behavioral effects of a school-based fruit and vegetable promotion program. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35(1):61–71. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoppu U, Lehtisalo J, Kujala J, Keso T, Garam S, Tapanainen H, et al. The diet of adolescents can be improved by school intervention. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(6A):973–9. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010001163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lytle LA, Murray DM, Perry CL, Story M, Birnbaum AS, Kubik MY, et al. School-based approaches to affect adolescents’ diets: results from the TEENS study. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):270–87. doi: 10.1177/1090198103260635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicklas TA, Johnson CC, Myers L, Farris RP, Cunningham A. Outcomes of a high school program to increase fruit and vegetable consumption: Gimme 5 - a fresh nutrition concept for students. J Sch Health. 1998;68(6):248–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1998.tb06348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perry CL, Bishop DB, Taylor G, Murray DM, Mays RW, Dudovitz BS, et al. Changing fruit and vegetable consumption among children: the 5-a-day power plus program in St. Paul, Minnesota. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(4):603–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.88.4.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radcliffe B, Ogden C, Welsh J, Carroll S, Coyne T, Craig P. The Queensland school breakfast project: a health promoting schools approach. Nutrition & Dietetics. 2005;62:33–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0080.2005.tb00007.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reynolds KD, Franklin FA, Binkley D, Raczynski JM, Harrington KF, Kirk KA, et al. Increasing the fruit and vegetable consumption of fourth-graders: results from the high 5 project. Prev Med. 2000;30(4):309–19. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.te Velde SJ, Brug J, Wind M, Hildonen C, Bjelland M, Perez-Rodrigo C, et al. Effects of a comprehensive fruit- and vegetable-promoting school-based intervention in three European countries: the Pro children study. Br J Nutr. 2008;99(4):893–903. doi: 10.1017/S000711450782513X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eather N, Morgan P, Lubans D. Improving the fitness and physical activity levels of primary school children: results of the Fit-4-Fun randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2013;56:12–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kriemler S, Zahner L, Schindler C, Meyer U, Hartmann T, Hebestreit H, et al. Effect of school based physical activity programme (KISS) on fitness and adiposity in primary schoolchildren: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c785. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simon C, Wagner A, Platat C, Arveiler D, Schweitzer B, Schlienger JL, et al. ICAPS: a multilevel program to improve physical activity in adolescents. Diabetes Metab. 2006;32(1):41–9. doi: 10.1016/S1262-3636(07)70245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wen LM, Fry D, Merom D, Rissel C, Dirkis H, Balafas A. Increasing active travel to school: are we on the right track? A cluster randomised controlled trial from Sydney, Australia. Prev Med. 2008;47(6):612–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arbeit ML, Johnson CC, Mott DS, Harsha DW, Nicklas TA, Webber LS, et al. The heart smart cardiovascular school health promotion: behavior correlates of risk factor change. Prev Med. 1992;21(1):18–32. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(92)90003-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brandstetter S, Klenk J, Berg S, Galm C, Fritz M, Peter R, et al. Overweight prevention implemented by primary school teachers: a randomised controlled trial. Obesity Facts. 2012;5:1–11. doi: 10.1159/000336255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caballero B, Clay T, Davis SM, Ethelbah B, Rock BH, Lohman T, et al. Pathways: a school-based, randomized controlled trial for the prevention of obesity in American Indian schoolchildren. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(5):1030–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.5.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colin-Ramirez E, Castillo-Martinez L, Orea-Tejeda A, Vergara-Castaneda A, Keirns-Davis C, Villa-Romero A. Outcomes of a school-based intervention (RESCATE) to improve physical activity patterns in Mexican children aged 8–10 years. Health Educ Res. 2010;25(6):1042–9. doi: 10.1093/her/cyq056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crespo NC, Elder JP, Ayala GX, Slymen DJ, Campbell NR, Sallis JF, et al. Results of a multi-level intervention to prevent and control childhood obesity among Latino children: the Aventuras Para Ninos study. Ann Behav Med. 2012;43:84–100. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9332-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Foster GD, Linder B, Baranowski T, Cooper DM, Goldberg L, Harrell JS, et al. A school-based intervention for diabetes risk reduction. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(5):443–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grydeland M, Bjelland M, Anderssen SA, Klepp K-I, Bergh IH, Andersen LF, Ommundsen Y, Lien N: Effects of a 20-month cluster randomised controlled school-based intervention trial on BMI of school-aged boys and girls: the HEIA study. Br J Sports Med 2013: doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-092284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Haerens L, Deforche B, Maes L, Stevens V, Cardon G, De B. Body mass effects of a physical activity and healthy food intervention in middle schools. Obesity. 2006;14(5):847–54. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jansen W, Borsboom G, Meima A, Joosten-Van Z, Mackenbach JP, Raat H, et al. Effectiveness of a primary school-based intervention to reduce overweight. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6:2–2. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2011.575151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Llargues E, Franco R, Recasens A, Nadal A, Vila M, Pérez Maria J, et al. Assessment of a school-based intervention in eating habits and physical activity in school children: the AVall study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:896–901. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.102319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luepker RV, Perry CL, McKinlay SM, Nader PR, Parcel GS, Stone EJ, et al. Outcomes of a field trial to improve children’s dietary patterns and physical activity. The child and adolescent trial for cardiovascular health (CATCH) JAMA. 1996;275(10):768–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03530340032026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rush E, Reed P, McLennan S, Coppinger T, Simmons D, Graham D. A school-based obesity control programme: project energize. Two-year outcomes. Br J Nutr. 2012;107:581–7. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511003151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sahota P, Rudolf MCJ, Dixey R, Hill AJ, Barth JH, Cade J. Randomised controlled trial of primary school based intervention to reduce risk factors for obesity. BMJ. 2001;323(7320):1029–32. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7320.1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sallis JF, McKenzie TL, Conway TL, Elder JP, Prochaska JJ, Brown M, et al. Environmental interventions for eating and physical activity: a randomized controlled trial in middle schools. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(3):209–17. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00646-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shamah Levy T, Morales Ruan C, Amaya CC, Salazar CA, Jimenez AA, Mendez Gomez H, et al. Effectiveness of a diet and physical activity promotion strategy on the prevention of obesity in Mexican school children. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:152. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trevino RP, Yin Z, Hernandez A, Hale DE, Garcia OA, Mobley C. Impact of the Bienestar school-based diabetes mellitus prevention program on fasting capillary glucose levels: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(9):911–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.9.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trevino RP, Hernandez AE, Yin Z, Garcia OA, Hernandez I. Effect of the Bienestar health program on physical fitness in low- income Mexican American children. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 2005;27(1):120–32. doi: 10.1177/0739986304272359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williamson DA, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, Han H, Martin Corby K, Newton Robert L, Jr, et al. Effect of an environmental school-based obesity prevention program on changes in body fat and body weight: a randomized trial. Obesity. 2012;20:1653–61. doi: 10.1038/oby.2012.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Vries H, Dijk F, Wetzels J, Mudde A, Kremers S, Ariza C, et al. The European smoking prevention framework approach (ESFA): effects after 24 and 30 months. Health Educ Res. 2006;121(1):116–32. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hamilton G, Cross D, Resnicow K, Hall M. A school-based harm minimization smoking intervention trial: outcome results. Addiction. 2005;100(5):689–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perry CL, Stigler MH, Arora M, Reddy KS. Preventing tobacco use among young people in India: project MYTRI mobilizing youth for tobacco-related initiatives in India. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(5):899–906. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.145433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wen X, Chen W, Gans KM, Colby SM, Lu C, Liang C, et al. Two-year effects of a school-based prevention programme on adolescent cigarette smoking in Guangzhou, China: a cluster randomized trial. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(3):860–76. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Komro KA, Perry CL, Veblen-Mortenson S, Farbakhsh K, Toomey TL, Stigler MH, et al. Outcomes from a randomized controlled trial of a multi-component alcohol use preventive intervention for urban youth: project Northland Chicago. Addiction. 2008;103(4):606–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Perry CL, Williams CL, Veblen-Mortenson S, Toomey TL, Komro KA, Anstine PS, et al. Project Northland: outcomes of a communitywide alcohol use prevention program during early adolescence. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(7):956–65. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.86.7.956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beets MW, Flay BR, Vuchinich S, Snyder FJ, Acock A, Li KK, et al. Use of a social and character development program to prevent substance use, violent behaviors, and sexual activity among elementary-school students in Hawaii. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(8):1438–45. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.142919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eddy JM, Reid JB, Stoolmiller M, Fetrow RA. Outcomes during middle school for an elementary school-based preventive intervention for conduct problems: follow-up results from a randomized trial. Behav Ther. 2003;34(4):535–52. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(03)80034-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Flay BR, Graumlich S, Segawa E, Burns JL, Holliday MY, Aban A. Effects of 2 prevention programs on high-risk behaviors among African American youth: a randomized trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(4):377–84. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.4.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li KK, Washburn I, Dubois D, Vuchinich S, Ji P, Brechling V, et al. Effects of the positive action programme on problem behaviours in elementary school students: a matched-pair randomised control trial in Chicago. Psychol Health. 2011;26(2):187–204. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.531574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perry CL, Komro KA, Veblen-Mortenson S, Bosma LM, Farbakhsh K, Munson KA, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the middle and junior high school D A R E and D A R E Plus programs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(2):178–84. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schofield MJ, Lynagh M, Mishra G. Evaluation of a health promoting schools program to reduce smoking in Australian secondary schools. Health Educ Res. 2003;18(6):678–92. doi: 10.1093/her/cyf048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Simons-Morton B, Haynie D, Saylor K, Crump AD, Chen R. The effects of the going places program on early adolescent substance use and antisocial behavior. Prevention Science. 2005;6(3):187–97. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Basen-Engquist K, Coyle KK, Parcel GS, Kirby D, Banspach SW, Carvajal SC, et al. Schoolwide effects of a multicomponent HIV, STD, and pregnancy prevention program for high school students. Health Educ Behav. 2001;28(2):166–85. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ross DA, Changalucha J, Obasi AIN, Todd J, Plummer ML, Cleophas-Mazige B, et al. Biological and behavioural impact of an adolescent sexual health intervention in Tanzania: a community-randomized trial. AIDS. 2007;21(14):1943–55. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282ed3cf5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bond L, Patton G, Glover S, Carlin JB, Butler H, Thomas L, et al. The Gatehouse project: can a multilevel school intervention affect emotional wellbeing and health risk behaviours? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(12):997–1003. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.009449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sawyer MG, Harchak TF, Spence SH, Bond L, Graetz B, Kay D, et al. School-based prevention of depression: a 2-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of the beyondblue schools research initiative. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(3):297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Orpinas P, Kelder S, Frankowski R, Murray N, Zhang Q, McAlister A. Outcome evaluation of a multi-component violence-prevention program for middle schools: the students for peace project. Health Educ Res. 2000;15(1):45–58. doi: 10.1093/her/15.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wolfe DA, Crooks C, Jaffe P, Chiodo D, Hughes R, Ellis W, et al. A school-based program to prevent adolescent dating violence: a cluster randomized trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(8):692–9. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cross D, Monks H, Hall M, Shaw T, Pintabona Y, Erceg E, et al. Three-year results of the friendly schools whole-of-school intervention on children’s bullying behaviour. Br Educ Res J. 2011;37(1):105–29. doi: 10.1080/01411920903420024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cross D, Waters S, Pearce N, Shaw T, Hall M, Erceg E, et al. The friendly schools friendly families programme: three-year bullying behaviour outcomes in primary school children. Int J Educ Res. 2012;53:394–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2012.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fekkes M, Pijpers FI, Verloove-Vanhorick SP. Effects of antibullying school program on bullying and health complaints. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(6):638–44. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.6.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Frey KS, Hirschstein MK, Snell JL, Van Schoiack Edstrom L, Mackenzie EP, Broderick CJ. Reducing playground bullying and supporting beliefs: an experimental trial of the Steps to Respect program. Dev Psychol. 2005;41(3):479–91. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kärnä A, Voeten M, Little Todd D, Poskiparta E, Kaljonen A, Salmivalli C. A large-scale evaluation of the KiVa antibullying program: grades 4–6. Child Dev. 2011;82:311–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kärnä A, Voeten M, Little Todd D, Alanen E, Poskiparta E, Salmivalli C. Effectiveness of the KiVa antibullying program: grades 1–3 and 7–9. J Educ Psychol. 2013;105(2):535–51. doi: 10.1037/a0030417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stevens V, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Van Oost P. Bullying in Flemish schools: an evaluation of anti-bullying intervention in primary and secondary schools. Br J Educ Psychol. 2000;70:195–210. doi: 10.1348/000709900158056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bowen A, Ma H, Ou J, Billhimer W, Long T, Mintz E, et al. A cluster-randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of a handwashing-promotion program in Chinese primary schools. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76(6):1166–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Talaat M, Afifi S, Dueger E, El-Ashry N, Marfin A, Kandeel A, et al. Effects of hand hygiene campaigns on incidence of laboratory-confirmed influenza and absenteeism in schoolchildren, Cairo, Egypt. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:619–25. doi: 10.3201/eid1704.101353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hall M, Cross D, Howat P, Stevenson M, Shaw T. Evaluation of a school-based peer leader bicycle helmet intervention. Inj Control Saf Promot. 2004;11(3):165–74. doi: 10.1080/156609704/233/289652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McVey G, Tweed S, Blackmore E. Healthy schools-healthy kids: a controlled evaluation of a comprehensive universal eating disorder prevention program. Body Image. 2007;4(2):115–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Olson AL, Gaffney C, Starr P, Gibson JJ, Cole BF, Dietrich AJ. SunSafe in the middle school years: a community-wide intervention to change early-adolescent sun protection. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):e247–56. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tai BJ, Jiang H, Du MQ, Peng B. Assessing the effectiveness of a school-based oral health promotion programme in Yichang City, China. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37(5):391–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2009.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jansen W, Raat H, Zwanenburg EJ, Reuvers I, van Welsen R, Brug J. A school-based intervention to reduce overweight and inactivity in children aged 6–12 years: study design of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:257. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Howerton MW, Bell BS, Dodd KW, Berrigan D, Stolzenberg-Solomon R, Nebeling L. School-based nutrition programs produced a moderate increase in fruit and vegetable consumption: meta and pooling analyses from 7 studies. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007;39(4):186–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Waters E, de Silva-Sanigorski A, Hall B, Brown T, Campbell K, Gao Y, et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011;12:CD001871. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001871.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Metcalf B, Henley W, Wilkin T. Effectiveness of intervention on physical activity of children: systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials with objectively measured outcomes (EarlyBird 54) BMJ. 2012;345:e5888. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol. 1985;14(1):32–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/14.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bonell C, Jamal F, Harden A, Wells H, Parry W, Fletcher A, et al. Systematic review of the effects of schools and school environment interventions on health: evidence mapping and synthesis. Public Health Research 2013;1(1):(doi:10.3310/phr01010) [PubMed]

- 91.Nutbeam D. Evaluating health promotion—progress, problems and solutions. Health Promot Int. 1998;13(1):27–44. doi: 10.1093/heapro/13.1.27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.World Health Organization Europe . Health Promotion Evaluation: Recommendations for Policy Makers. Copenhagen: WHO Working group on Health Promotion Evaluation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rychetnik L, Frommer M, Hawe P, Shiell A. Criteria for evaluating evidence on public health interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56(2):119–27. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.2.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Complex interventions: how “out of control” can a randomised controlled trial be? BMJ. 2004;328(7455):1561–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7455.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.International Union for Health Promotion and Education . Promoting Health in Schools: From evidence to Action. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 96.International Union for Health Promotion and Education . Achieving health promoting schools: guidelines for promoting health in schools. Version 2 of the document formerly known as “Protocols and guidelines for health promoting schools”. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Thomas R, McLellan J, Perrera R. School-based programmes for preventing smoking. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;4:CD001293. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001293.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Farrington D, Ttofi M: School-Based Programs to Reduce Bullying and Victimization. Campbell Systematic Reviews 2009, [10.4073/csr.2009.6]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 99.Natcen UCL. Health Survey for England 2012: Health, Social Care and Lifestyles. Leeds: Health and Social Care Information Centre; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Berkman DS, Lescano AG, Gilman RH, Lopez SL, Black MM. Effects of stunting, diarrhoeal disease, and parasitic infection during infancy on cognition in late childhood: a follow-up study. Lancet. 2002;359(9306):564–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07744-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Grantham-McGregor S. A review of studies of the effect of severe malnutrition on mental development. J Nutr. 1995;125(8 Suppl):2233S–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.suppl_8.2233S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Keats S, Wiggins S. Future Diets. Implications for Agriculture and Food Prices. London: Overseas Development Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 103.United Nations . World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision, Highlights and Advance Tables. New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bonell C, Humphrey N, Fletcher A, Moore L, Anderson R, Campbell R. Why schools should promote students’ health and wellbeing. BMJ. 2014;348:g3078. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]