Summary

Complete cycling of mineral nitrogen (N) in soil requires the interplay of microorganisms performing nitrification and denitrification, whose activity is increasingly affected by extreme rainfalls or heat brought about by climate change.

In a pristine forest soil, a gradual increase in soil temperature from 5°C to 25°C at a range of water contents stimulated N turnover rates and N gas emissions were determined by the soil water-filled pore space (WFPS). NO and N2O emissions dominated at 30% WFPS and 55% WFPS respectively and the step-wise temperature increase resulted in 3-fold increased NO3− concentrations and decreased NH4+ concentrations. At 70% WFPS NH4+ accumulated, whereas NO3− pools declined indicating gaseous N loss. AmoA- and nirK gene based analysis revealed increasing abundance of bacterial ammonia oxidizers (AOB) with rising soil temperature, whereas decreased abundance of archaeal ammonia oxidizers (AOA) in wet soil at 25°C suggested sensitivity to anaerobic conditions. Denitrifying (nirK) community structures were most affected by the water content and nirK gene abundance rapidly increased in response to wet conditions until substrate (NO3−) became limiting. Shifts in the community structure were most pronounced for nirK and rapid for AOA, indicating dynamic populations, whereas adaptations of the AOB communities required five weeks, suggesting higher stability.

Keywords: nitrification, denitrification, NO, N2O emission, nirK, amoA, T-RFLP, qPCR, clone library

Introduction

Nitrification and denitrification represent key processes determining the availability and form of N in soils and are held responsible for gaseous nitrogen losses as NO or N2O, both of which act as potent greenhouse gases.

The ability to denitrify is widespread among various microbial taxa, including phylogenetically diverse groups (Zumft, 1997). For instance, nirK and nirS genes, encoding the key enzyme nitrite reductase, have been assigned to unrelated affiliations (Phillipot, 2002). Conversely, nitrification was long believed to be restricted to a monophyletic group of bacteria, until recent studies attributed environmental amoA homologues to members of the Crenarchaeota phylum within the domain Archaea (Treusch et al., 2005). The interplay between nitrite reducers, ammonia oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and ammonia oxidizing archaea (AOA) is determined by environmental parameters such as soil temperature and soil water content (Wallenstein et al., 2006; Avrahami et al., 2007). Nitrification and denitrification, which together complete the cycling of mineral N in soil, have optima under different environmental conditions, but may also occur simultaneously (Gödde & Conrad, 1999).

Potential changes in the world’s climate are expected to entail an increase in extreme events (Easterling et al., 2000), including a higher frequency of intense precipitation, increases in extreme high temperatures, decreases in extreme low temperatures, heat waves and drought (Schär et al., 2004; IPCC, 2007). The capacity of nitrifiers and denitrifiers to respond to such short-term changes in the environment, corresponding NO and N2O emissions and subsequent implications on mineral N balances, are however, poorly understood.

Previous studies have reported rapidly altered activities of soil nitrifiers and denitrifiers in response to changing environmental conditions. Incubation for 5 days at temperatures up to 37°C caused a markedly decrease in NH4+ and an increase in NO3− concentrations in agricultural soils (Avrahami et al., 2003). Despite the rapid stimulation of nitrification activity, a slow adaptation to changing soil temperature has been attributed to soil ammonia oxidizing bacteria. Community changes were detected after 16 weeks in agricultural soils and after 8 to 16 weeks in meadow soils (Avrahami et al., 2003; Avrahami & Conrad, 2003), indicating a decoupling of activity and community responses. Archaeal amoA communities have previously demonstrated higher dynamics by responding to soil temperature within 12 days of incubation at temperatures between 10°C and 30°C (Tourna et al., 2008).

The initiation of NO and N2O production within minutes of wetting dry grassland soils (Davidson, 1992) demonstrated a rapid activation of denitrification in soil. However, a lack of response of denitrifying communities (nosZ) to changes in temperature and water content suggested a high stability of denitrifying communities (Stres et al., 2008).

Whereas most previous studies of the effects of soil moisture and temperature have focused on either investigating activity responses, fluxes of N oxides or adaptations on the community/abundance level, the challenge of this study was to combine functional and structural responses with the aim to draw a more complete picture of the interplay between nitrification and denitrification.

In order to explore short-term changes in N cycling processes in soil, we investigated the capacity of nitrifying (ammonia oxidizing bacteria and archaea) and denitrifying (nitrite reducing) functional groups to adapt to a changing environment. In soils at three water contents changes in gene abundances, community structure and related microbial activities were monitored continuously throughout a constant increase in temperature.

The subject of the study was the pristine Rothwald spruce-fir-beech forest, which has experienced a long history of undisturbed evolution since the last ice-age and represents the biggest remnant of pristine temperate forests in Central Europe. The Rothwald forest has previously been shown to host a threefold higher diversity of microbiota than other natural forest soils in Austria (Hackl et al., 2004). For this reason, the Rothwald forest offered a unique opportunity to study the responsiveness of putative nitrifiers and denitrifiers and the regulation of nitrogen balances under gradually changing environmental conditions in a well-equilibrated forest ecosystem.

Materials and Methods

Soil sampling

In October 2004 samples of mineral soil were taken from the Rothwald forest, which comprises 460 ha of pristine forest located in a remote valley in Lower Austria at 1035 m above sea level. The Rothwald spruce-fir-beech forest is situated on dolomite bedrock, the soil type is Chromic Cambisol with a pH value of 5.3 and a C:N ration of 17.1. Mean annual precipitation amounts to 1759 mm and the average temperature is 5.5°C (Hackl et al., 2004). Ten individual samples (0-10 cm depth) were collected at intervals of 5 m along a 50 m transect. The 10 individual soil samples were sieved (2 mm mesh) and combined to form one homogenous soil sample in order to exclude variability in aeration and compaction.

Soil incubation

Soil microcosms were established in fifteen stainless steel soil cylinders of 7.5 cm diameter and 5 cm height, filled with approximately 120 g homogenised fresh soil. Soil water contents were adjusted to either 30%, 55% or 70% water-filled pore space (WFPS), by drying in ambient air or wetting with distilled water using a syringe. The soil cores were established in five replicates per soil moisture level and were pre-incubated at 5°C for one week with periodical readjustment of the water content. During the experiment the soil temperature was increased weekly in four 5°C increments from 5 to 25°C. Three days after increasing the temperature, soil samples were taken from incubated soil cores for analysis of mineral nitrogen concentrations and nitrogen turnover rates. At each temperature, one soil core of each moisture level was sampled destructively for replicated determination of NH4+ and NO3− concentrations and measurement of nitrogen turnover processes (nitrate reductase-activity, nitrification rate, N-mineralisation) in four subsamples. Nitrogen trace gas fluxes (NO, N2O) were measured in four replicate soil cores at each moisture level. During the gas measurements soil cores were kept at the respective incubation temperature for 4 days. Following process measurements, soils were stored at −20°C for subsequent DNA extraction.

Gas-flux analysis

The NO emission from the soil cores was measured after 4 days of incubation with a fully automated system operated by a personal computer as described by Schindlbacher et al. (2004). An incubator containing 13 temperature-controlled test chambers was linked to a chemo-luminescence nitrogen oxide analyzer (HORIBA-APNA-360). The soil cores were placed in individual test chambers with one empty jar serving as a control. The NO concentration in the flow-through stream of each vessel was analysed separately at intervals of eight minutes, generating more than 60 NO measurements per sample throughout the analyses.

For N2O measurements, the soil cores were incubated in gas-tight test chambers (headspace volume 450 ml, n=4) at controlled temperatures. Head-space gas samples of 15 ml were taken with a syringe immediately after closure, after 3 h and after 6 h of incubation. The gas samples were transferred to 10 ml evacuated glass vials, sealed with silicone grease and stored under water at 4°C until analysis. Nitrous oxide concentrations were analysed by gas chromatography (HEWLETT-PACKARD 5890 Series II, injector: 120°C, detector: 330°C, oven: 120°C, carrier gas: N2) using a 63Ni electron capture detector. Nitrous oxide fluxes were calculated from the linear increase in concentration over the incubation time and corrected for air temperature and pressure.

Nitrogen turnover rates and mineral nitrogen pools

Nitrification and nitrate reductase activities were measured after 4 days of incubation and involved the addition of dissolved substrates or inhibitors to the individual assays. For maintaining the adjusted WFPS, substances were applied in 400 μl aqueous solution to 2.5 g soil aliquots of each treatment. This volume corresponded to the amount of water evaporating during 24 h of incubation (data not shown).

Nitrate reductase-activity was measured according to Schinner et al. (1996) using KNO3 as a substrate (final concentration 0.0625M) and dinitrophenole (DNP) as inhibitor of nitrite reductase. Preliminary tests showed optimal inhibition at a concentration of 7 × 10−3 mg DNP g−1dry Rothwald soil (data not shown). The substrate-DNP solution was applied to 2.5 g soil aliquots of each treatment (n=6) with a micro-syringe followed by mixing. Four replicates were kept at the respective temperature for 24 h and two samples, serving as blanks, were immediately frozen at −20°C. Total NO2− from samples and blanks was extracted with 3M KCl and analysed photometrically (μQuant, BIO TEC Instruments, Inc.). Nitrate reductase activities were calculated according to Schinner et al. (1996).

In order to measure the nitrification rate NaClO3 (0.234 M), serving as an inhibitor of NO2− oxidation (Belser & Mays, 1980), was applied to 2.5 g soil aliquots (n=6). Two samples per treatment, serving as blanks, were frozen at −20°C and four replicates were incubated for 24 h at the respective temperature. Nitrite was extracted with 2M KCl and analysed photometrically. Nitrification rates were calculated as described by Schinner et al. (1996). Nitrite concentrations of the individual treatments were calculated from blanks (nitrification rate, nitrite reductase activity), used for determining background NO2− concentrations (n=4). For measuring mineralisation rates acetylene was used as an inhibitor of ammonia oxidation (Berg et al., 1982). Soil aliquots of 5 g (n=3) were incubated in gas-tight glass flasks (Volume 13 cm3) under 3 % acetylene-atmosphere. Ammonium was extracted before and after incubation at the respective temperature as described below and mineralisation rates were calculated according to Schinner et al. (1996).

Ammonium, nitrite and nitrate were extracted from 5 g of fresh soil samples with 30 ml CaCl2 (0.0125 M) with shaking for 30 min (n=3). In filtered soil extracts NH4+-N was detected photometrically at 660 nm while NO3−-N was determined as NO2− after overnight reduction with copper sheathed granulated zinc at 210 nm (Schinner et al., 1996).

DNA extraction and quantification of nirK, bacterial and archaeal amoA by real-time PCR

DNA was extracted from 0.5 g aliquots of incubated soil samples using the FastDNA Spin Kit for soil (Qbiogene). Three replicate DNA extractions of individual soil cores were pooled prior to PCR amplification. Functional marker genes encoding nitrite reductase (nirK), archaeal and bacterial ammonia monooxygenase (archaeal amoA, bacterial amoA) were quantified in triplicate by real-time PCR using an iCycler IQ (Biorad). The 25 μl PCR reaction mix contained 10 mg/ml BSA, 0.675 μl DMSO, 12.5 μl of Q Mix (Biorad, 100 mM KCl, 40 mM Tris-HCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM each of dNTP, 50U/ml iTaq DNA Polymerase, SybrGreen I, 20 nM fluorescein, and stabiliser) and 25-50 ng template. Fluorescent acquisition was performed at 77°C for nirK, at 81°C for bacterial amoA and at 78°C for archaeal amoA, where all primer dimers had melted but specific products had not. For the quantification of nirK 1 μl (of a 10 μM solution) of each PCR primer nirK1F (GGMATGGTKCCSTGGCA) and nirK5R (GCCTCGATCAGRTTRTGG) were added to the PCR mix, resulting in a 514 bp product (Braker et al., 1998). The cycling conditions were 95°C for 3 min, 6 touch-down cycles of 15 s at 95°C, 30 s at 63°C (decreasing 1°C per cycle), 30 s at 72°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, then 58°C, 72°C, 77°C for 30 s each. The quantification of bacterial amoA fragments (491 bp) was performed using the primer pair amoA-1F (GGGGTTTCTACTGGTGGT) and amoA-2R (CCCCTCKGSAAAGCCTTCTTC) (Rotthauwe et al., 1997) of which 1.25 μl (10 μM each) were added to the reaction mix. The cycling conditions were 95°C for 3 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C, 57°C, 72°C, 81°C for 1 min each. The archaeal amoA gene real-time PCR reaction contained 0.75 μl (10 μM each) of the primers Arch-amoAF (STAATGGTCTGGCTTAGACG) and Arch-amoAR (GCGGCCATCCATCTGTATGT) (10 μM each) according to Francis et al. (2005), resulting in a 635 bp product. The cycling conditions were 95°C for 5 min, followed by 45 cycles of 45 s at 95°C, 45 s at 53°C, 60 s at 72°C and 60 s at 78°C. Amplification of nirS using the primer pairs Cd3aF and R3cd according to Throbäck et al. (2004) or nirS 1F and nirS 1R according to Braker et al. (1998) failed to produce PCR product.

Abundances of nirK, bacterial and archaeal amoA genes were calculated as copy number per gram dry soil. In addition, gene copy number per ng DNA were calculated and correlated to gene copy numbers per gram soil. Plasmids containing the respective functional gene as an insert (nirK, bacterial amoA or archaeal amoA) were isolated from clones using Easy Prep Pro (Biozym). Standards for qPCR were generated by serial dilution of stocks of a known number of plasmid containing the respective functional gene.

Reaction efficiencies of qPCRs were 94.5% (± 2.5) for nirK, 98% (± 2) for archaeal amoA and 76.5% (±3.5) for bacterial amoA and R2 values were 0.99 for all runs. No inhibitory effects on qPCR amplification were detected when serially diluted Rothwald soil DNA was spiked with known concentrations of standard plasmids (nirK, AOA, AOB).

Community profiling by T-RFLP analysis

For T-RFLP analysis, fluorescently end-labelled forward primers (carboxyfluorescein phosphoramidite marked - FAM) were used for the amplification of nirK and bacterial and archaeal amoA genes. The primer sets used were nirK1F-FAM and nirK5R for amplifying nirK, amoA-1F-FAM and amoA-2R for bacterial amoA, and Arch-amoAF-FAM and Arch-amoAR for archaeal amoA. PCR amplifications, performed in T1 thermocyclers (Biometra), involved an initial denaturation-step at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 38 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 40 s at 54.4°C, 60 s at 72°C, followed by a final elongation step of 72°C for 5 min. Amplifications were performed in 25 μl reactions containing 2.5 μl (2 μM each) of the primer set, 2.5 μl dNTPs (2 mM), 3 μl MgCl2 (25 mM), 2.5 μg BSA (Sigma, 10 mg/ml), 1 μl DMSO, ~50 ng DNA, 1 U Firepol Polymerase (Solis Biodyne) and 1 × reaction buffer provided with the enzyme.

For generating T-RFLP profiles three replicate PCR reactions from each sample were pooled and purified with Invisorb Spin PCRapid Kit (Invitek) before digestion as recommended by Hartmann et al. (2007). FAM marked bacterial and archaeal amoA PCR products were digested with RsaI restriction enzyme (Invitrogen) at 37°C for 3 to 4 h. The FAM marked nirK products were digested with TaqI restriction enzyme (Promega) at 65°C for 3 to 4 h. Each digest was conducted in 10 μl reaction volume containing 200 ng FAM marked PCR-product, 1 μl reaction buffer and 2U of the respective restriction enzyme. Digests were purified using Sephadex columns. HIDI loading buffer (Formamide) and GeneScan-500 ROX length standard for sizing DNA fragments in the 35-500 bp range (Applied Biosystems) were added to the digests, which were then denatured at 92°C for 2 min prior to analysis on a ABI Prism 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Terminal restriction fragments (T-RFs) for each sample were calculated as described previously (Abell et al., 2009). Briefly fragments of each gene were compared to the internal standard using the GeneScan software package (Version 3.7, Applied Biosystems), only fragments between 50 and 600 bp were included in the analysis. The area of each peak was expressed as a percentage of the total peak area in the profile and peaks comprising less than 1.5% of the total area were removed from the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance was performed using the ANOVA multiple Range Test (Statgraphics Plus 5.0) on mineral nitrogen pools, nitrogen turnover processes, gene abundances and on AOA:AOB ratios. A LSD test was used for comparison of samples with equal size numbers, whilst the Scheffé test was used for samples with varying numbers of replicates. Mineral nitrogen pools, nitrogen turnover rates and the abundance of the functional genes were subjected to principal component analysis, PCA (SAS, Enterprise guide 2). The significance of relationships between parameters represented by vectors with similar or opponent orientation was explored via multiple-variable analysis (Statgraphics Plus 5.0).

For the analysis of T-RFLP data statistical analysis was performed on standardised, square-root transformed data using Primer 6 software (PRIMER-E, Plymouth UK). Non-metric multidimensional scaling (nmMDS) using Bray-Curtis similarity calculation was used for demonstrating the relatedness of individual community profiles under different treatments (Kenkel & Orloci, 1986; Minchin, 1987). Similarity between treatments on the basis of T-RFLP profiles was calculated using the one-way univariate analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) including 10000 permutations with significant differences considered at p<0.01% (Clarke, 1993). A similarity percentage analysis (SIMPER) was used to identify the major T-RFs responsible for observed differences between treatments. To identify differences in the T-RF abundance, presence or absence between specific treatments ANOVA (Scheffé test, 95% confidence) was used (Buckley & Schmidt, 2001).

Results

Mineral nitrogen pools

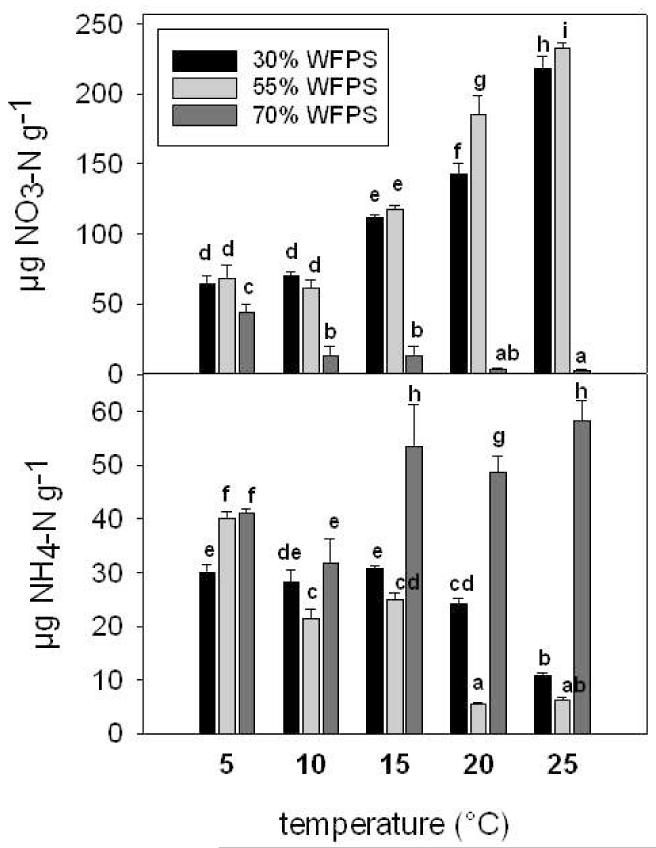

With increasing soil temperature NO3− concentrations at 30% and 55% WFPS increased (Fig. 1) and were 3 times higher at 25°C compared to 5°C. Under O2 limiting conditions at 70% WFPS, the soil NO3− concentration decreased with increasing temperature and was 19 times lower at 25°C than at 5°C. As a consequence, at 25°C NO3− concentrations were 90 times higher at 30% and 55% WFPS compared to soil at 70% WFPS.

Figure 1.

Mean NO3− content (NO3-N μg g−1 soil) and mean NH4+ content (NH4-N μg g−1 soil) at 30 % WFPS, 55 % WFPS and 70 % WFPS and 5°C, 10°C, 15°C, 20°C and 25°C. Error bars represent the standard deviation. Different lower case characters represent significant differences, p<0.05, LSD test

The increase in NO3− concentrations occurred simultaneously to an overall decrease in NH4+ concentrations with increasing soil temperature at 30% and 55% WFPS. This resulted in 3- and 6-fold lower NH4+ concentrations at 25°C compared to 5°C at 30% and 55% WFPS (Fig. 1). At 15°C, 20°C and 25°C, NH4+ concentrations were comparably high in soil at 70% WFPS. Consequently, at 25°C NH4+ concentrations were 5- and 9-fold higher at 70% WFPS as compared to 30% WFPS and 55% WFPS.

Nitrite concentrations (data not shown) were low in comparison to NO3− and NH4+ concentrations. The maximum NO2− concentrations reached 2.4 μg NO2−-N g−1 soil at 20°C and 70% WFPS and 1.4 μg NO2−-N g−1 soil at 15°C and 55% WFPS. In all other treatments NO2− concentrations were ≤ 1μg NO2−-N g−1 soil.

Nitrogen turnover processes

At all water contents mineralisation rates were increased at higher soil temperatures, resulting in up to 14-fold higher mineralisation at 25°C compared to 5°C (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean values of mineralisation (μg NH4-N g−1 24 h−1), nitrate reductase activity (μg N g−1 24 h−1) and nitrification rate (ng N g−1 24 h−1) in the Rothwald soil at 30% WFPS, 55% WFPS and 70% WFPS and 5°C, 10°C, 15°C, 20°C and 25°C. Different lower case characters represent significant differences, p<0.05.

| mineralisation | nitrate reductase | nitrification | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (°C) | 30 % WFPS | 55 % WFPS | 70 % WFPS | 30 % WFPS | 55 % WFPS | 70 % WFPS | 30 % WFPS | 55 % WFPS | 70 % WFPS | |||||||||

| 5 | 0.7 | abc | −0.3 | a | 0.4 | ab | −0.1 | a | 0.1 | a | −0.2 | a | −1.8 | a | 79.5 | ab | 122.8 | abc |

| 10 | 0.1 | ab | 1.5 | abc | 4.0 | de | 0.8 | abc | 1.2 | abc | 0.0 | a | 183.3 | abc | 529.8 | abc | −14.3 | abc |

| 15 | 1.5 | abc | 2.5 | bcd | −0.8 | ab | 1.8 | abc | 3.1 | bc | 0.2 | ab | 48.4 | abc | 985.2 | bc | 106.8 | abc |

| 20 | 1.5 | abc | 4.3 | def | 3.0 | cd | 2.5 | abc | 13.3 | e | 10.1 | d | 452.4 | abc | 2404.2 | d | 1063.8 | c |

| 25 | 4.8 | def | 6.5 | f | 5.4 | ef | 3.3 | c | 14.2 | e | 7.8 | d | 398.5 | abc | 3014.8 | d | 629.0 | abc |

Mineralisation rates at 55% WFPS were highest and increased uniformly with the soil temperature (R2=0.95, p<0.0001) between 5°C and 25°C. The increase in mineralisation rate at 30% WFPS and 70% WFPS was not uniform at each temperature level.

Nitrification rates increased most rapidly at 55% WFPS (Table 1), resulting in 38 times higher nitrification rates at 25°C as compared to 5°C (R2=0.72, p<0.0001). In other treatments the temperature response was masked by sample variability. Nitrification was highest in soil at 55% WFPS when compared to 30% and 70% WFPS soils.

Nitrate reductase activities increased at higher soil temperatures at all water contents, with the highest activity measured at 55% WFPS (Table 1). At this moisture level also the highest (113-fold) increase in activity from 5°C to 25°C was measured. At 30% WFPS the activity increase was steady but low (R2=0.84, p<0.0001). At 55% and 70% WFPS, where conditions were more reductive, instead of a uniform increase escalating peak activities at 20°C and 25°C were measured.

Nitrogen oxide gas fluxes

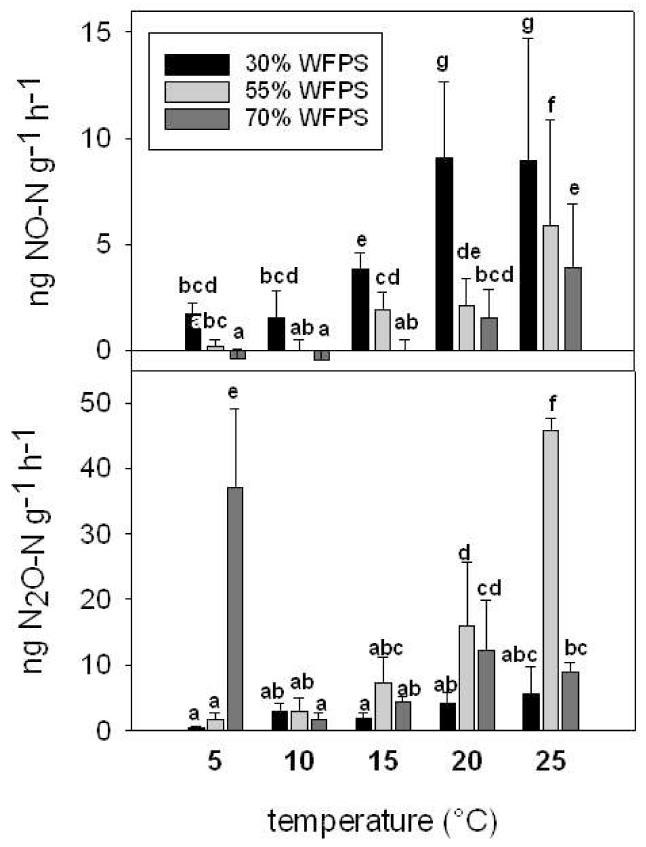

Nitric oxide emissions were highest at 30% WFPS and lowest at 70% WFPS but increased at all water contents with increasing soil temperature (Fig. 2). The steepest (39-fold) increase in NO emission from 5°C and 25°C was measured at 55% WFPS.

Figure 2.

Mean NO emission (ng NO-N g−1 h−1) and mean N2O emission (ng N2O-N g−1 h−1) at 30% WFPS, 55% WFPS and 70% WFPS and 5°C, 10°C, 15°C, 20°C and 25°C. Error bars represent the standard deviation. Different lower case characters represent significant differences, p<0.05, Scheffé test

At all water-contents N2O emissions tended to increase with rising soil temperature (Fig. 2). At 55% WFPS N2O emissions were highest and a statistically significant (28-fold) exponential increase (R2=0.82, p<0.0001) occurred with rising soil temperature. At 5°C N2O peaked at 70% WFPS with 79 and 23 times higher N2O emissions as compared to 30% and 55% WFPS.

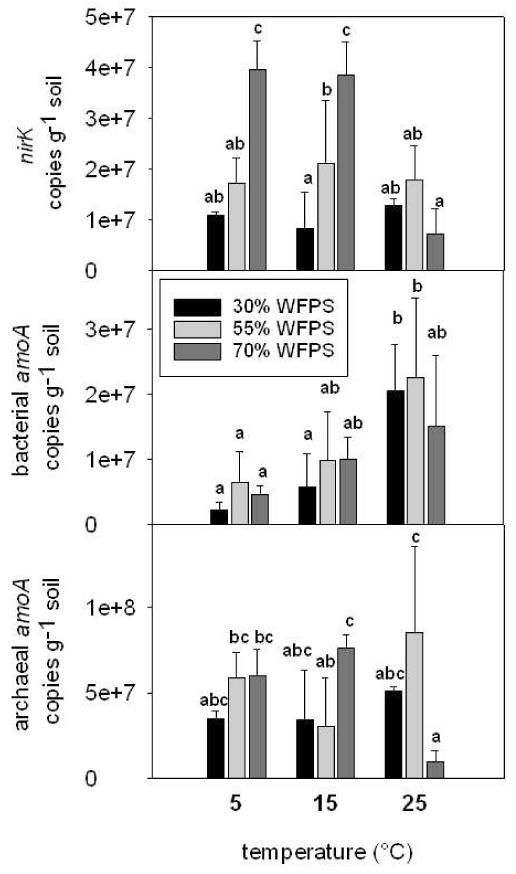

Quantification of nirK, archaeal and bacterial amoA genes

The abundance of nirK genes ranged from 6.4 × 106 to 4.0 × 107 copies g−1 soil within soils at the various WFPS levels (Fig. 3). At 70% WFPS nirK gene copy numbers were highest at 5°C and 15°C but at 25°C the nirK abundance decreased 5-fold respective to the lower temperatures. At 5°C and 15°C nirK genes were also more abundant at 70% WFPS than at 55% and 30% WFPS. A significant overall temperature effect on the nirK gene abundance was not observed.

Figure 3.

Mean abundance of nirK, bacterial amoA, archaeal amoA genes (copies g−1 soil) at 30% WFPS, 55% WFPS and 70% WFPS and 5°C, 15°C and 25°C. Error bars represent the standard deviation. Different lower case characters represent significant differences at the 95% confidence level, p<0.05, LSD test

Bacterial amoA gene copy numbers ranged from 2.4 × 106 to 2.2 × 107 copies g−1 and increased with rising soil temperature (Fig. 3). From 5°C to 25°C bacterial amoA abundance increased 3- and 9-fold at 55% and 30% WFPS, respectively. The soil water content had no significant effect on the bacterial amoA gene abundance.

Archaeal amoA genes were detected in high abundances ranging from 1.1 × 107 to 8.1 × 107 copies g−1 soil (Fig. 3). At 70% WFPS the archaeal amoA gene abundance was 8 times higher at 15°C than at 25°C. A significant overall effect of soil water content and temperature on the abundance of archaeal amoA genes was, however, not observed.

The interpretation of the qPCR results was the same when they were expressed as gene copies ng−1 DNA or copies g−1 soil, there was a strong linear relationship between the two measures (AOA: R2 0.90, AOB: R2 0.61, nirK: R2 0.89; p<0.0001).

Across the different soil temperatures, archaeal amoA genes were between 0.7 to 15.5 times as abundant as bacterial amoA genes. Archaeal amoA abundance comprised 90-94%, 75-88% and 40-79% of the total amoA abundance at 5°C, 15°C and 25°C, respectively, indicating an effect of temperature on the AOA:AOB ratio. The AOA:AOB ratio decreased significantly with increasing soil temperature at 70% WFPS (p=0.001). At 30% WFPS AOA/AOB ratios were lower at 15°C and 25°C than at 5°C (p<0.05). The same tendency was observed for soil at 55% WFPS although at a not significant level (p=0.1).

T-RFLP community analysis

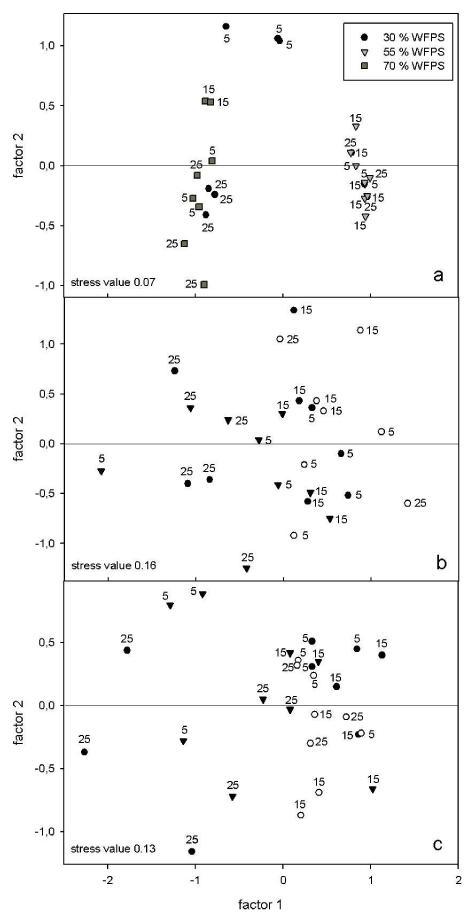

Community profiles of the nirK gene revealed a total of 61 peaks in all profiles with 1 major peak (200 bp) and 3 peaks (74 bp, 103 bp, 244 bp length) having an abundance of 20% and of >5% of the total abundance, respectively. Samples subjected to the same treatment clearly clustered in a nmMDS plot with a stress value of 0.07 (Fig. 4a). ANOSIM analysis indicated significant differences between nirK communities according to the water content (global R=0.55, p=0.01%) and a combinational effect of water content and temperature (global R=0.67, p=0.01%). At all incubation temperatures the nirK community structure varied according to the three water contents. After one week of incubation at 5°C the nirK communities at 30% WFPS, 55% WFPS and 70% WFPS differed among each other (R=1, p=0.01). The main difference between treatments was attributed to a range of T-RFs (60 bp, 101 bp, 103 bp, 135 bp, 242 bp, 244 bp and 387 bp length), as their presence/absence varied significantly according to the water content (p<0.001). After 3 weeks of incubation with increasing temperature up to 15°C the nirK community structure at 70% WFPS differed significantly from the ones at 55% WFPS and 30 % WFPS (R=1, p=0.01). The differences between treatments can be ascribed to the T-RFs of 101 bp, 242 bp and 387 bp in length, which were highly abundant at 70% WFPS but were undetected at 55% WFPS and 30% WFPS (p=0.0000). After 5 weeks of incubation with increasing temperature up to 25°C the nirK community structure at 55% WFPS differed from the ones at 30% WFPS and 70% WFPS (R=1, p=0.01). The difference between treatments can be attributed to the T-RFs of 60 bp, 101 bp and 244 bp length as their presence/absence varied significantly between the water levels at 25°C (p=0.000). The nirK community structures at 30% WFPS varied according to the incubation time with increasing temperature and differed at 5°C, 15°C and 25°C. A range of T-RFs (60 bp, 101 bp, 244 bp, 242 bp, 74 bp, 103 bp, 387 bp, 135 bp) contributed to this difference as they demonstrated different presence/absence patterns according to the incubation temperatures (p<0.001).

Figure 4.

Plots (nmMDS) based on Bray-Curtis similarities showing the relative similarities within a) nirK and within b) bacterial amoA and within c) archaeal amoA T-RFLP profiles at 30% WFPS, 55% WFPS and 70% WFPS and 5°C, 15°C and 25°C. Numbers in the plot (5, 15, 25) represent the respective incubation temperatures.

Bacterial amoA community profiles showed a total number of 27 peaks in all profiles including 4 dominant peaks at 250 bp, 273 bp, 376 bp, 485 bp length, which comprised of >10 % of the total abundance and 3 peaks (268 bp, 274 bp, 373 bp) which comprised of >5 % of the total abundance. One replicate from the treatment group 55% WFPS at 25°C contained an outlier which was eliminated prior to analysis. The nmMDS plot with a stress value of 0.16 showed some differences between treatments (Fig. 4b). This was further supported by an ANOSIM test demonstrating an interactional effect of WFPS and increasing temperature (global R=0.36, p=0.02 %). SIMPER analysis revealed a range of T-RFs responsible for the differences between treatments of which only one (378 bp) showed significant variation between the treatments (p=0.0000). The T-RF of 378 bp was abundant at 25°C and 30% WFPS (p=0.0000) but absent in the other treatments. After 5 weeks of incubation with increasing temperature up to 25°C, the AOB community at 30% WFPS differed in structure from the ones at 5°C (R=1, p=0.01) and 15°C (R=0.78 p=0.01) after 1 and 3 weeks of incubation, respectively. According to SIMPER analysis ~9 % of the differences between treatments were attributed to a T-RF of 378 bp in length. After 5 weeks of incubation with increasing temperature up to 25°C, the AOB community structures at 55% WFPS differed from those at 30% WFPS (R=0.67, p=0.01) and 70% WFPS (R=0.5, p=0.02). At 70% WFPS the AOB community structures at 25°C and 15°C were different (R=0.67, p=0.01). SIMPER analysis revealed a range of T-RFs accounting for this difference, however none of them demonstrated a significantly increased abundance in any of the treatments.

Analysis of archaeal amoA community profiles demonstrated a total of 47 T-RFs across all profiles of which 4 dominant fragments (58 bp, 60 bp, 138 bp, 300 bp) length) comprising an abundance of >10% of the total abundance and a further 3 fragments comprising an abundance of >5% of the total abundance (130 bp, 170 bp, 196 bp) were detected. A significant difference between some treatments is demonstrated in an nmMDS plot with a stress value of 0.13 (Fig. 4c). ANOSIM analysis indicated a significant combinational treatment effect of water content and increasing temperature on the archaeal amoA community structure (global R=0.36, p=0.01%). SIMPER analysis and subsequent statistical analysis identified 4 T-RF fragments (67 bp, 138 bp, 283 bp, 490 bp) to which the main difference between treatments were attributed, as their presence/absence varied between treatments. The AOA community at 70% WFPS after 1 week of incubation at 5°C differed in structure from the ones at 15°C (R=0.78, p=0.01) and 25°C (R=0.63, p=0.01) after 3 and 5 weeks of incubation, respectively. Among a range of T-RF fragments, respectively contributing with >6% to the dissimilarity between the treatments, the T-RFs of 283 bp and 67 bp in length were present and highly abundant at 70% WFPS and 5°C however were absent or of negligible abundance at 15°C and 25°C (p=0.000). After 1 week of incubation at 5°C the AOA community at 70% WFPS was differently structured than the ones at 30% WFPS (R=0.96, p=0.01) and 55% WFPS (R=0.89, p=0.01). Three T-RFs of 67 bp, 138 bp and 283 bp in length accounted for 6%, 10% and 7% of these differences, respectively. At 5°C the T-RF of 67 bp and 283 bp in length were abundant at 70% WFPS however absent at 55% WFPS and 30% WFPS (p=0.000), whereas the T-RF of 138 bp in length was abundant at 30% WFPS and 55% WFPS but not at 70% WFPS (p=0.0003). After 5 weeks of incubation with increasing temperature up to 25°C the AOA community structure at 30% WFPS differed from the ones at 55% WFPS (R=0.96, p=0.01) and 70% WFPS (R=0.78, p=0.01). Two T-RFs of 67 bp and 490 bp in length were most abundant at 25°C and 30% WFPS but absent at 55% and 70% WFPS (p=0.0000). After 5 weeks of incubation with increasing temperature up to 25°C the AOA community structure at 30% WFPS differed from those at 5°C (R=1, p=0.01) and 15 °C (R=1, p=0.01). These differences can be partially explained by the T-RF of 490 bp which was most abundant at 30 % WFPS and 25°C but absent at 5°C and 15°C (p=0.0000) and by the T-RF of 138 bp in length which was abundant at 5°C but of negligible abundance at 25°C (p=0.0003).

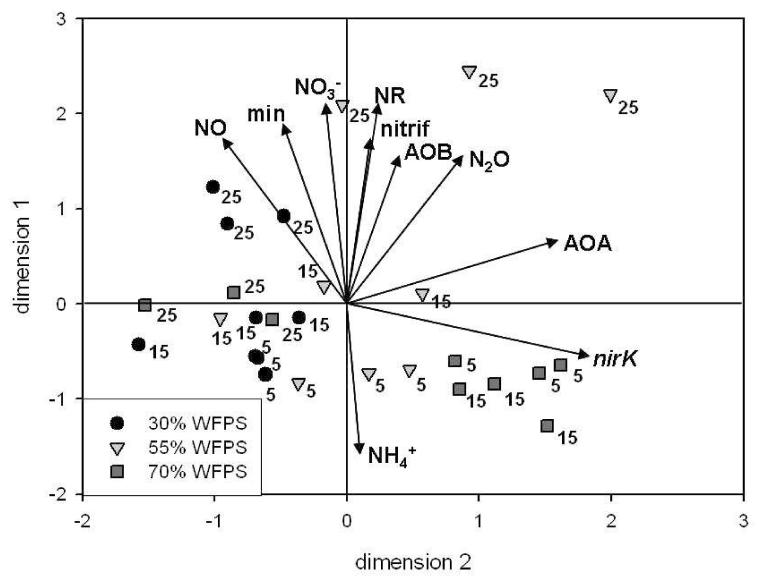

Principal component analysis

Principal component analysis including data on N concentrations, process rates and gene abundances, explored three factors with Eigenvalues > 1 which together accounted for 79.5% of the variability in the data. In a PC plot of two factors which together explained 68% of the variability, individual samples clustered according to the treatment (Fig. 5). Individual samples incubated at 5°C and 15°C had mostly negative y-values, whereas samples incubated at 25°C had mostly positive y-values, resulting in a temperature gradient running along the y-axis. The position of individual samples respective to the vectors indicated the key parameters contributing to the differences between the treatments. The nirK abundance was the key determinant at 70% WFPS with samples incubated at 5°C and 15°C clustering alongside the nirK vector. Soil at 30% WFPS, located on the left side of the y-axis, was ordinated with higher NO emissions.

Figure 5.

Principal component analysis of mineral nitrogen pools, process data and real-time PCR data at 30% WFPS, 55% WFPS and 70% WFPS and 5°C, 15°C and 25°C. Arrows represent the abundance of nirK (nirK), bacterial amoA (AOB) and archaeal amoA (AOA) genes, the mineralisation rate (min), nitrate reductase activity (NR), nitrification rate (nitrif), contents of nitrate (NO3−) and ammonium (NH4+) and emissions of nitric oxide (NO) and nitrous oxide (N2O).

Vectors with a similar orientation indicated a relationship between the parameters analysed which was further explored by statistical analysis. The mineral nitrogen forms NO3− and NH4+ were negatively related (R2 −0.96, p<0.05) as suggested by the opposing orientations of the respective vectors in the PCA plot. Nitrate concentrations were closely related to NO emission rates (R2 0.69, p<0.001), to the nitrification rate (R2 0.56, p<0.001), to the mineralisation rate (R2 0.55, p<0.001) and correlated positively with the AOB abundance (R2 0.52, p<0.05), the nitrate reductase activity (R2 0.49, p<0.05) and N2O emission rates (R2 0.34, p<0.05). Contrastingly, NH4+ contents were negatively related to NO emission rates (R2 −0.58, p<0.0001) and correlated negatively with the nitrification rate (R2 −0.49, p<0.05), the AOB gene abundance (R2 −0.38, p<0.05) and the nitrate reductase activity (R2 −0.37, p<0.05).

Discussion

Soil moisture and temperature effects on N turnover processes

A gradual increase in soil temperature from 5°C to 25°C evoked a rapid stimulation of nitrogen cycling rates along with a shift in the balance of NO3− and NH4+ concentrations at all three moisture levels. Different processes were driving nitrogen cycling at the various soil water contents, resulting in changes in the availability of mineral nitrogen forms. During the series of weekly temperature increases, NO3− steadily accumulated in dry and moist soils. Along with NO3− concentrations, nitrification rates increased most rapidly under a moderate water content (55% WFPS), where NH4+ concentrations and water supply appeared to be favourable. However, in wet soil the NO3− pool decreased continuously and was almost depleted at 25°C. This nitrate loss observed under wet conditions can be attributed to complete denitrification and liberation of N2 gas to the atmosphere (Davidson & Swank, 1986). Soil moisture was the major determinant of N2O or NO emissions from the Rothwald soil. The production of NO mostly in dry soils during nitrification, and of N2O in moist soils due to denitrification, have been proposed by Firestone & Davidson (1989). Our study widely confirms these theories since most NO was emitted at 30% WFPS while N2O emissions were highest at 55% WFPS. This moisture-effect was not reflected in the abundances of AOB and AOA. However, the nirK abundance clearly increased with increasing water content until the NO3− supply became limiting. In spite of the high nirK abundances at 70% WFPS, being suggestive for favourable nitrite reducing conditions, the lowest amounts of NO and medium N2O levels were emitted under these conditions. Following the onset of anaerobiosis, N2O reduction exceeds the rate of N2O production with N2 being the dominant product of denitrification (Firestone & Tiedje, 1979). We suggest that under increasingly anoxic conditions at 70% WFPS the intermediates NO and N2O were not liberated but further reduced to N2, since many nitrite reducers also possess other denitrification genes enabling them to perform several steps of the denitrification pathway (Phillipot, 2002). Precipitation events, in the same way as experimental wetting, may evoke sudden N2O peaks from the Rothwald forest soil as also reported for dry grassland soils (Davidson, 1992) and for Amazon forest soils (Garcia-Montiel et al., 2003).

Temporally high NO3−, but low NH4+ availability was observed as a consequence of low water availability and high temperature in the Rothwald soil. Conversely, wet conditions seem likely to cause NH4+ to accumulate, whereas a strong decline in NO3− pools may occur even in cold seasons. This implies that in wet soils nitrogen gas emissions can be high even at low temperatures, as was indicated by a high N2O peak at 5°C and 70% WFPS. Peak N2O emissions at 0°C from forest soils (Öquist et al., 2004) have previously been explained by a shift in the N2O to N2 ratio towards enhanced N2O emissions, caused by a suppression of N2O reductases at low temperatures (Dörsch & Bakken, 2004). Stres et al. (2008) reported persistent N2O emissions at low temperature and high water content during 12 weeks of incubation, noting that N2O emission in cold soils may be controlled by nitrification (Öquist et al., 2007) as NO3 contents were not depleted.

Structure and abundance of functional communities responding to soil moisture and temperature

The reported activity responses were accompanied by adaptations of microbial community structures and resulted in significant shifts in the functional gene abundances of bacterial and archaeal ammonia oxidizers and nitrite reducers.

Of all three groups, nitrite reducers showed the highest responsiveness to environmental changes. Potential nitrite reducers increased most rapidly in their abundance, and their community structure shifted most explicitly in response to changes in soil temperature and water content. The soil water content demonstrated a significant impact on nitrite reducers, as the nirK community structure varied according to the water content at all temperature increments. Accordingly, nirK gene copy numbers increased with increasing water content until NO3− became limiting. In contrast to the distinct response of Rothwald forest soil denitrifiers, only minor changes in the nosZ denitrifier community structure were observed in fen grassland during 12 weeks of incubation at modified soil water contents and soil temperatures (Stres et al., 2008). The Rothwald forest, as compared to 11 natural Austrian forests, was characterised as extraordinarily rich in nutrients, hosting high microbial biomass and showing strong internal nutrient cycling (Hackl et al., 2004, Hackl et al., 2004a; Hackl et al., 2005). The rapid community response of denitrifiers to variations in soil parameters may originate from particular characteristics of this pristine forest soil.

Ammonia oxidising archaea in the Rothwald soil demonstrated a capacity to respond to environmental changes within a short time span. Under extreme conditions, in wet soil (70% WFPS) at low temperature (5°C) or in dry soil (30% WFPS) at increasing temperature up to 25°C, AOA communities differed in structure. The rapid community adaptation under wet conditions, which was detectable after only one week at 5°C, indicates sensitivity of AOA to high water contents. Accordingly, sensitivity of AOA to reductive conditions was suggested by the significant decrease in archaeal amoA abundance at 70% WFPS and 25°C, where conditions were likely oxygen limited. In contrast to previously described AOA community shifts in response to temperature variation (Tourna et al., 2008) and despite temperature being considered a key factor determining microbial growth, in the Rothwald soil temperature did not uniformly affect archaeal amoA gene copy numbers.

Among the ammonia oxidising community, AOA were more dynamic than AOB. Communities of AOB appeared more stable, as the community structure differed according to the treatment firstly at 25°C, after five weeks of incubation with gradually increasing temperature. This may indicate a just beginning shift in the community structure of AOB, whose adaptation has been reported to require several weeks. By applying DGGE analysis Avrahami et al. (2003) demonstrated that incubation times of at least 16 weeks were required for AOB to adapt to changing environmental conditions in agricultural soils. DGGE patterns from high fertilisation treatments induced community shifts after only 6.5-12 weeks of incubation (Avrahami et al., 2003), indicating ammonia as a selective factor for the community response of ammonia oxidizers. In a more recent study, community shifts of betaproteobacterial ammonia oxidizers were induced after a seven-week incubation of grassland soils and could be detected using T-RFLP analysis but not with less sensitive DGGE techniques (Avrahami & Bohannan, 2007), indicating the divergence of results obtained by different fingerprinting techniques (Moeseneder et al., 1999). However, AOB communities generally appeared to be of higher stability compared to AOA and though may represent the K strategists among the nitrifiers in the Rothwald soil. A high potential for heterotrophic nitrification has been ascribed previously to acidic soils between pH 4-6 (Pedersen et al., 1999, Schimel et al., 1984). However, it was stated that heterotrophic nitrifiers use organic N compounds rather than NH4+-N as substrate for nitrification (Islam et al., 2007). In the Rothwald soil heterotrophic nitrification may be of only minor importance, since a strong negative correlation between NH4+ and NO3− concentrations indicated that NH4+ may represent the main source for NO3− production through autotrophic nitrification.

Consistent with previous findings (Leininger et al., 2006), AOA were more abundant than AOB in the Rothwald soil. However, the relative abundance of AOB in the Rothwald soil increased with increasing soil temperature in wet soils. At 5°C bacterial amoA genes comprised only ~10% of the total amoA gene abundance, but their relative abundance increased significantly at higher soil temperatures. This change in the ratio of AOA to AOB amoA gene abundance resulted from a stimulation of AOB growth at elevated soil temperatures, whilst the abundance of AOA did not increase. He et al. (2007) found that both, AOB and AOA amoA gene copy numbers were higher in summer compared to winter in Chinese upland red soil, indicating a seasonal effect on both groups of ammonia oxidizers. However, divergent responses of AOA and AOB to soil pH (Nicol et al., 2008), salinity (Santoro et al., 2008), N fertilisation (Shen et al., 2008) and soil temperature and moisture in the present study, provide evidence for a coexistence of AOA and AOB in distinct niches. The observed shifts in the microbial community structures and changing gene abundances of nirK, bacterial and archael amoA suggest an impact on N cycling by altering the potential to reduce nitrate or oxidise ammonia, respectively. It needs to be considered that the conversion of inorganic N forms by nitrifiers and denitrifiers however serves different purposes. Changes in the abundance and community structure of the mostly heterotrophic dentitrifiers may relate to the uptake rates of organic C, rather than resulting from denitrification. Conversely, bacterial ammonia oxidizers as chemolithotrophic autotrophs have low growth rates (Ferguson et al., 2007). Archaeal ammonia oxidizers are still metabolically uncharacterised but are believed to grow either autotrophic or mixotrophic (Hallam et al., 2006; Prosser & Nicol, 2008). Consequently, the ability to transform inorganic nitrogen forms depends on the availability of the respective C source required.

Conclusion

Results of this study showed that short-term changes in the precipitation regime and soil temperature may rapidly affect the activity of both nitrifiers and denitrifiers, accompanied by changes in source/sink strength of soils for nitrogen oxides and the availability of mineral nitrogen forms in forest ecosystems. A general stimulation of nitrogen turnover rates was observed as temperatures were increased. Different processes were driving N cycling at the various water contents, resulting in variable mineral N balances. This study clearly demonstrated different capacities of functional groups involved in nitrogen cycling to respond to short-term changes in the soil environment.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF). We thank Brigitte Schraufstädter, Michael Pfeffer, Thomas Gschwantner, Barbara Kitzler, Katrin Ripka and Andreas Schindlbacher for their contributions.

References

- Abell GCJ, Revill AT, Smith C, Bissett AP, Volkman JK, Robert SS. Archaeal ammonia oxidizers and nirS-type denitrifiers dominate sediment nitrifying and denitrifying populations in a subtropical macrotidal estuary. ISME. 2009 doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.105. doi:10.1038/ismej.2009.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avrahami S, Liesack W, Conrad R. Effects of temperature and fertilizer on activity and community structure of soil ammonia oxidizers. Environ Microbiol. 2003;5:691–705. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avrahami S, Conrad R. Patterns of community change among ammonia oxidizers in meadow soils upon long-term incubation at different temperatures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:6152–6164. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.10.6152-6164.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avrahami S, Bohannan BJM. Response of Nitrosospira sp. strain AF-like ammonia oxidizers to changes in temperature, soil moisture content, and fertilizer concentration. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:1166–1173. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01803-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belser LW, Mays EL. Specific inhibition of nitrite oxidation by chlorate and its use in assessing nitrification in soils and sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980;39:505–510. doi: 10.1128/aem.39.3.505-510.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg P, Klemedtsson L, Rosswall T. Inhibitory effect of low partial pressures of acetylene on nitrification. Soil Biol Biochem. 1982;14:301–303. [Google Scholar]

- Braker G, Fesefeldt A, Witzel KP. Development of PCR primer systems for amplification of nitrite reductase genes (nirK and nirS) to detect denitrifying bacteria in environmental samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3769–3775. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3769-3775.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley DH, Schmidt TM. The structure of microbial communities in soil and the lasting impact of cultivation. Microb Ecol. 2001;42:11–21. doi: 10.1007/s002480000108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke KR. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Austral J Ecol. 1993;18:117–143. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson EA, Swank WT. Environmental parameters regulating gaseous nitrogen losses from two forested ecosystems via nitrification and denitrification. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;52:1287–1292. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.6.1287-1292.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson EA. Sources of nitric oxide and nitrous oxide following wetting of dry soil. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 1992;56:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Dörsch P, Bakken LR. Low-temperature response of denitrification: comparison of soils. Euras Soil Sci. 2004;37:102–106. [Google Scholar]

- Easterling DR, Evans JL, Groisman PY, Karl TR, Kunkel KE, Ambenje P. Observed variability and trends in extreme climate events: a brief review. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 2000;81:417–425. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SJ, Richardon DJ, Van Spanning RJM. Biochemistry and molecular biology of nitrification. In: Bothe H, Ferguson SJ, Newton WE, editors. Biology of the nitrogen cycle. Amsterdam; Elsevier: 2007. pp. 209–221. [Google Scholar]

- Firestone M, Tiedje JM. Temporal change in nitrous oxide and dinitrogen from denitrification following onset of anaerobisis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979;38:673–679. doi: 10.1128/aem.38.4.673-679.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firestone MK, Davidson EA. Microbiological basis of NO and N2O production and consumption in soil. In: Andreae MO, Schimel DS, editors. Exchange of trace gases between terrestrial ecosystems and the atmosphere. Wiley; Berlin: 1989. pp. 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Montiel DC, Steudler PA, Piccolo M, Neill C, Melillo J, Cerri CC. Nitrogen oxide emissions following wetting of dry soils in forest and pastures in Rondonia, Brazil. Biogeochemistry. 2003;64:319–336. [Google Scholar]

- Gödde M, Conrad R. Immediate and adaptational temperature effects on nitric oxide production and nitrous oxide release from nitrification and denitrification in two soils. Biol Fertil Soils. 1999;30:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hackl E, Bachmann G, Zechmeister-Boltenstern S. Microbial nitrogen turnover in soils under different types of natural forest. Forest Ecol Manag. 2004;188:101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hackl E, Zechmeister-Boltenstern S, Bodrossy L, Sessitsch A. Comparison of diversities and compositions of bacterial populations inhabiting natural forest soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004a;70:5057–5065. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.9.5057-5065.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackl E, Pfeffer M, Donat C, Bachmann G, Zechmeister-Boltenstern S. Composition of the microbial communities in the mineral soil under different types of natural forests. Soil Biol and Biochem. 2005;37:661–671. [Google Scholar]

- Hallam SJ, Mincer TJ, Schleper C, Preston CM, Roberts KJ, Richardson PM, DeLong EF. Pathways of carbon assimilation and ammonia oxidation suggested by environmental genomic analyses of marine Crenarchaeota. PLOS Biology. 2006;4:520–536. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann M, Enkerli J, Widmer F. Residual polymerase activity-induced bias in terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. Environmental Microbiology. 2007;9:555–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Shen J, Zhang L, Zhu Y, Zheng Y, Xu M, Di H. Quantitative analyses of the abundance and composition of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and ammonia-oxidizing archaea of a Chinese upland red soil under long-term fertilization practices. Environ Microbiol. 2007;9:2364–2374. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IPCC Intergovernmental panel on climate change Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report, Summary for Policymakers. 2007;4:1–2. Assessment Report. [Google Scholar]

- Islam A, Chen D, White RE. Heterotrophic and autotrophic nitrification in two acid pasture soils. Soil Biol Biochem. 2007;39:972–975. [Google Scholar]

- Kenkel NC, Orloci L. Applying metric and nonmetric multidimentsional scaling to some ecological studies: some new results. Ecol. 1986;67:919–928. [Google Scholar]

- Leininger S, Urich T, Schloter M, et al. Archaea predominate among ammonia-oxidizing prokaryotes in soils. Nature. 2006;17:806–809. doi: 10.1038/nature04983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minchin PR. An evaluation of the relative robustness of techniques for ecological ordination. Plant Ecol. 1987;69:89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Moeseneder MM, Arrieta JM, Muyzer G, Winter C, Herndl G. Optimization of terminal-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis for complex marine bacterioplankton communities and comparison with denaturing gradient gel electophoresis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3518–3525. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.8.3518-3525.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicol GW, Leininger S, Schleper C, Prosser JI. The influence of soil pH on the diversity, abundance and transcriptional activity of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:2966–2978. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öquist MG, Nilsson M, Sörensson F, Kasimir-Klemedtsson A, Persson T, Weslien P, Klemedtsson L. Nitrous oxide production in a forest soil at low temperatures-processes and environmental controls. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2004;49:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öquist MG, Petrone K, Nilsson M, Klemedtsson L. Nitrification controls N2O production rates in a frozen boreal forest soil. Soil Biol and Biochem. 2007;39:1809–1811. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen H, Dunkin KA, Firestone M. The relative importance of autotrophic and heterotrophic nitrification in a conifer forest soil as measured by 15N tracer and pool dilution techniques. Biogeochem. 1999;44:135–150. [Google Scholar]

- Philippot L. Denitrifying genes in bacterial and archaeal genomes. BBA. 2002;1577:355–376. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(02)00420-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser JI, Nicol GW. Relative contributions of archaea and bacteria to aerobic ammonia oxidation in the environment. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:2931–2941. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotthauwe JH, Witzel KP, Liesack W. The ammonia monoxygenase structural gene amoA as a functional marker: molecular fine-scale analysis of natural ammonia-oxidizing populations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;62:4704–4712. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.12.4704-4712.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro AE, Francis CA, de Sieyes NR, Boehm AB. Shifts in the relative abundance of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and archaea across physicochemical gradients in a subterranean estuary. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:1068–1079. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schär C, Vidale PL, Lüthi D, Frei C, Häberli C, Liniger MA, Appenzeller C. The role of increasing temperature variability in European summer heatwaves. Letters to Nature. 2004;427:332–336. doi: 10.1038/nature02300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimel JP, Firestone M, Killham KS. Identification of heterotrophic nitrification in a Sierran forest soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;48:802–806. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.4.802-806.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindlbacher A, Zechmeister-Boltenstern S, Butterbach-Bahl K. Effects of soil moisture and temperature on NO, NO2, and N2O emissions from European forest soils. J Geophys Res. 2004;109:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Schinner F, Öhlinger R, Kandeler E, Margesin R. Methods in Soil Biology. Springer Verlag; Berlin: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Zhang L, Zhu Y, J Z, He J. Abundance and composition of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and ammonia-oxidizing archaea communities of an alkaline sandy loam. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:1601–1611. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stres B, Danevcic T, Pal L, et al. Influence of temperature and soil water content on bacterial, archaeal and denitrifying microbial communities in drained fen grassland soil microcosms. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2008;66:110–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourna M, Freitag TE, Nicol GW, Prosser JI. Growth, activity and temperature responses of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria in soil microcosms. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:1357–1364. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treusch AH, Leininger S, Kletzin A, Schuster SC, Klenk HP, Schleper C. Novel genes for nitrite reductase and Amo-related proteins indicate a role of uncultivated mesophilic Crenarchaeota in nitrogen cycling. Environ Microbiol. 2005;7:1985–1995. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Throbäck IN, Enwall K, Jarvis A, Hallin S. Reassessing PCR primers targeting nirS, nirK and nosZ genes for community surveys of denitrifying bacteria with DGGE. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2004;49:401–417. doi: 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallenstein MD, Myrold DD, Firestone M, Voytek M. Environmental controls on denitrifying communities and denitrification rates: insights from molecular methods. Ecol Appl. 2006;16:2143–2152. doi: 10.1890/1051-0761(2006)016[2143:ecodca]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zumft WG. Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiol Molec Biol Rev. 1997;61:533–616. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.4.533-616.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]