Abstract

Objective:

We investigated the determinants and clinical correlations of MRI-detected brain volume loss (BVL) among patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis from the phase 3 trials of fingolimod: FREEDOMS, FREEDOMS II, and TRANSFORMS.

Methods:

Post hoc analyses were conducted in the intent-to-treat populations from each trial and in a combined dataset of 3,635 patients from the trials and their extensions. The relationship between brain volume changes and demographic, clinical, and MRI parameters was studied in pairwise correlations (Pearson) and in multiple regression models. The relative frequency of confirmed disability progression was evaluated in the combined dataset by strata of concurrent BVL at up to 4 years.

Results:

Increasing age, disease duration, T2 lesion volume, T1-hypointense lesion volume, and disability were associated with reduced brain volume (p < 0.001, all). The strongest individual baseline predictors of on-study BVL were T2 lesion volume, gadolinium-enhancing lesion count, and T1-hypointense lesion volume (p < 0.01, all). During each study, BVL correlated most strongly with cumulative gadolinium-enhancing lesion count, new/enlarged T2 lesion count (p < 0.001, both), and number of confirmed on-study relapses (p < 0.01). Over 4 years in the combined dataset (mean exposure to study drug, 2.4 years), confirmed disability progression was most frequent in patients with greatest BVL.

Conclusions:

Rate of BVL in patients during the fingolimod trials correlated with disease severity at baseline and new disease activity on study, and was associated with worsening disability.

Brain volume loss (BVL) is widespread in multiple sclerosis (MS),1 and occurs throughout the disease course at a rate considerably greater than in the general population.2–6 In MS, brain volume (BV) correlates with and predicts future disability,1,7–10 making BVL a relevant measure of diffuse CNS damage leading to clinical disease progression, as well as serving as a useful outcome in evaluating MS therapies.11–13

Fingolimod 0.5 mg (Gilenya; Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland) consistently reduced annual BVL by approximately one-third compared with comparator in 3 pivotal phase 3 studies conducted in patients with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS).14–16 Herein, we present exploratory analyses of each of these trials and of a combined population (n = 3,635) from the trials and their extensions. We aimed to investigate the clinical relevance of brain atrophy by analyzing correlations between normalized BV (NBV) and baseline MRI or clinical activity, by identifying baseline factors that predict on-study BVL, and by assessing longitudinal relationships between concurrent changes in BV and in MRI and clinical parameters.

METHODS

Patients and study design.

The study designs and patient eligibility criteria for FTY720 Research Evaluating Effects of Daily Oral Therapy in MS (FREEDOMS), FREEDOMS II, Trial Assessing Injectable Interferon vs FTY720 Oral in RRMS (TRANSFORMS), and their study extensions have been reported previously.14–19 All 3 were randomized, double-blind studies conducted in patients with RRMS. In FREEDOMS (NCT00289978) and FREEDOMS II (NCT00355134), patients received fingolimod 0.5 mg, 1.25 mg, or placebo. In TRANSFORMS (NCT00340834), patients received fingolimod 0.5 mg, 1.25 mg, or interferon β-1a (IFNβ-1a) IM.

Patients receiving comparator were rerandomized 1:1 to receive fingolimod 0.5 mg or 1.25 mg at enrollment into the extensions to FREEDOMS (NCT00662649) and TRANSFORMS (NCT00340834). Patients rerandomized to fingolimod 1.25 mg were subsequently switched to open-label fingolimod 0.5 mg after a protocol amendment. Patients receiving placebo switched to open-label fingolimod 0.5 mg in the extension to FREEDOMS II (NCT00340834). Of 3,635 patients in the combined analysis, 3,634 were exposed to study drug for a total of 8,616 patient-years, with a mean exposure of 2.4 years and maximum exposure of 4.9 years.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

All patients gave written informed consent. The studies were conducted in accordance with International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, and with the Declaration of Helsinki.20,21

Outcome measures and procedures.

Using a standardized scanning protocol,14 MRI scans (T2-weighted and T1-weighted pre- and postcontrast administration, 3-mm slice thickness) were obtained in all studies at screening (performed within 30 days before randomization), at month 6 (except in TRANSFORMS), and at months 12, 24, 36, and 48. Calculation of BV change was performed using the structural image evaluation using normalization of atrophy (SIENA; v3.3 [TRANSFORMS] or v4.1 [FREEDOMS and FREEDOMS II]) software (FMRIB [Oxford Centre for Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain], Oxford, UK), and of BV at baseline using SIENA cross-sectional (SIENAX).22 In all cases, when running SIENA, MS MRI lesions were not masked and the provider's default settings were used. Clinical assessments were performed at screening, baseline, and scheduled study visits. The Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score was determined every 3 months, and the MS Functional Composite (MSFC) score every 6 months.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed in the intent-to-treat populations from baseline to end of study in the 2-year FREEDOMS and FREEDOMS II trials and in the 1-year TRANSFORMS trial. Additional analyses were conducted up to 4 years from baseline in a combined dataset that included all available data from the 3 trials and their extensions. Certain correlation values presented from analysis of the TRANSFORMS population are reported elsewhere23 (for details, see tables e-1 to e-3 on the Neurology® Web site at Neurology.org).

Baseline correlations.

To investigate the association between BV and MS disease characteristics, Pearson and Spearman correlations were determined pairwise between baseline NBV and 9 baseline parameters: age; duration of MS since first symptoms; number of relapses 1 or 2 years before the study; disability, measured using EDSS and MSFC scores; gadolinium (Gd)-enhancing lesion number; T2 lesion volume; and T1-hypointense lesion volume. Pearson correlation coefficients are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p values determined using Fisher z transformation. Spearman correlations were in good agreement with the Pearson correlations, did not alter the interpretation of the results, and thus are not reported. In a further analysis, the following statistical model selection process was defined and used to identify the best baseline predictors of NBV, detecting common patterns across the 3 studies. (1) A forward model selection process based on multiple regression models and Akaike Information Criterion was conducted separately for each study. (2) The order of importance was ranked within each study (unselected variables were given a rank of 10), and ranks were then averaged across studies to weight the studies equally. The best baseline predictors were defined as those with the lowest mean ranks across studies. Only candidate variables that were consistently selected in all studies were considered for inclusion in the final model. (3) The analysis was repeated, excluding MSFC as a candidate variable. (4) A multiple linear regression model was used to investigate the combined effect of more than one explanatory variable on NBV. The final model was fitted to all 3 studies for parameter estimation.

Baseline predictors of percentage BV change on-study.

Pairwise Pearson and Spearman correlations were determined between percentage BV change (PBVC) on-study and each of 10 biologically plausible baseline predictors of BVL: NBV and the 9 parameters specified above (in the section baseline correlations). Pearson correlations are presented with 95% CIs and p values. Spearman correlations were similar to the Pearson correlations and are not reported. In a further analysis, a similar model selection process as described above for NBV (steps 1–3) was conducted to identify the best baseline predictors of on-study BVL. A final multiple regression model with treatment and the 2 best predictors (baseline T2 lesion volume and baseline number of Gd-enhancing lesions) was then refitted to the data from each of the 3 studies to quantify PBVC as a function of the best predictors. No adjustment was made for multiplicity. This final model was defined with treatment as a factor and with Gd-enhancing lesion count and T2 lesion volume at baseline as continuous covariates. Key numbers from this model are presented. In addition, to provide insights into possible interactions, an expanded model with all possible 2-way interactions was evaluated for specific values of the predictor. Estimated PBVC is presented graphically as a function of the best baseline predictors from this expanded model.

Longitudinal correlations on-study.

To explore the association between PBVC on-study and concurrent changes in MRI and clinical outcome variables, pairwise Pearson and Spearman correlations were calculated between PBVC on-study and changes in the following 7 parameters on-study: number of confirmed relapses; EDSS and MSFC scores; cumulative number of Gd-enhancing lesions; T2 lesion volume; number of new/enlarged T2 lesions; and T1-hypointense lesion volume. Pearson correlations are presented with 95% CIs and p values. Spearman correlations were similar to the Pearson correlations and are not reported.

PBVC and disability.

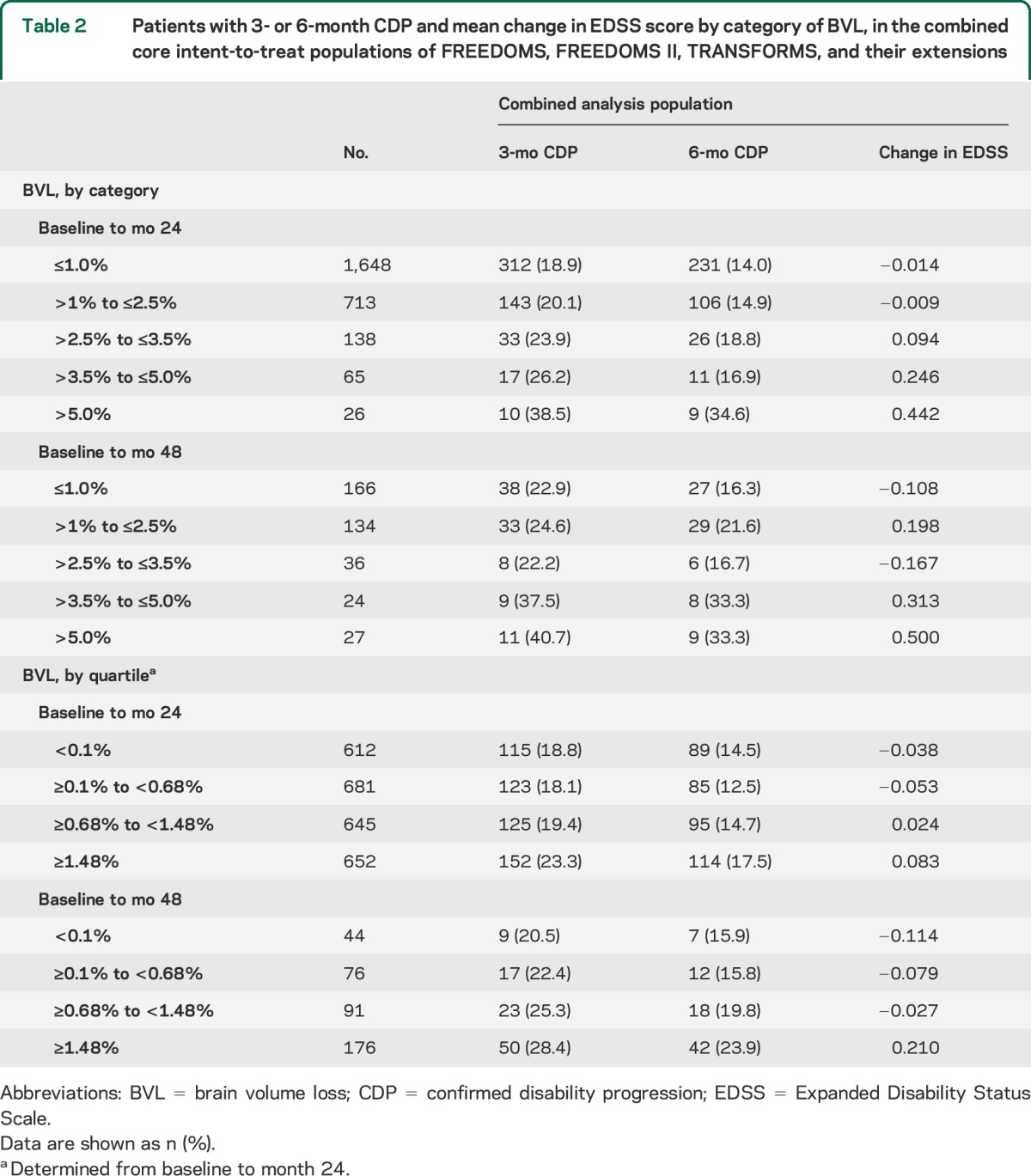

To investigate the association between BVL and disability, Pearson correlations were calculated between PBVC from baseline and change in EDSS score from baseline at months 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 in the combined analysis population and in patient subgroups with 3- and 6-month confirmed disability progression (CDP); correlations are presented with 95% CIs and p values. The incidence of patients in the combined analysis population with 3- or 6-month CDP and the corresponding mean change in EDSS score were summarized by category of BVL.

RESULTS

Baseline correlations among NBV, patient demographics, and disease characteristics.

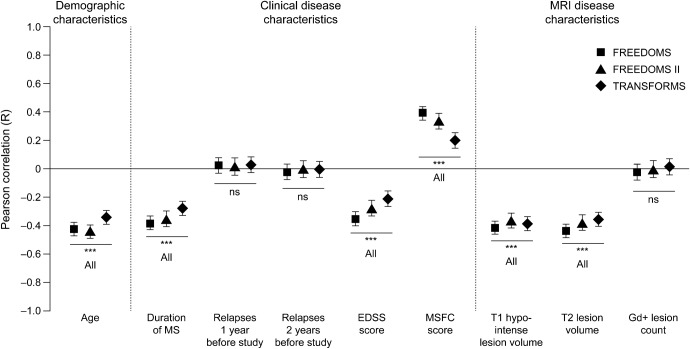

In the 3 studies, baseline NBV decreased as age, duration of MS, T1-hypointense and T2 lesion volumes, and levels of disability increased (figure 1). Baseline NBV was slightly greater in women than men in FREEDOMS (1,518 vs 1,506 cm3; p = 0.0167) and FREEDOMS II (1,530 vs 1,494 cm3; p < 0.0001) but not in TRANSFORMS (1,526 vs 1,524 cm3; p = 0.6592). These between-sex differences were <0.5 SD (14.5%, 43.8%, 0.3%, respectively) and thought unlikely to be of clinical significance. In general, the normalization algorithm in SIENAX reduced between-sex differences, possibly overcompensating slightly in the FREEDOMS studies.

Figure 1. Baseline correlation between normalized brain volume and age, and clinical and MRI disease characteristics.

Pearson correlations are shown ± 95% confidence intervals; values are given in table e-1. The correlation between normalized brain volume and MSFC score is positive, because MSFC score decreases as disability increases. ***p < 0.001. EDSS = Expanded Disability Status Scale; Gd+ = gadolinium-enhancing; MS = multiple sclerosis; MSFC = Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite; ns = not significant.

Age, baseline T2 lesion volume, duration of MS, and measures of baseline disability (EDSS or MSFC) correlated independently with NBV in all studies. The multiple regression model always ranked MSFC above EDSS, but selected EDSS in all studies when MSFC was excluded. In the final model, age, T2 lesion volume, duration of MS, and MSFC score were significant, independent variables explanatory of NBV in all 3 studies (p ≤ 0.0001, all). The total variability in baseline NBV between individual patients accounted for by this combination of 4 variables (unadjusted R2) was as follows: 39.5% in FREEDOMS (R, 0.63), 36.5% in FREEDOMS II (R, 0.60), and 23.8% in TRANSFORMS (R, 0.49; p < 0.0001, all). When MSFC was substituted with EDSS in the model, similar results were obtained (data not shown).

Baseline predictors of PBVC on-study.

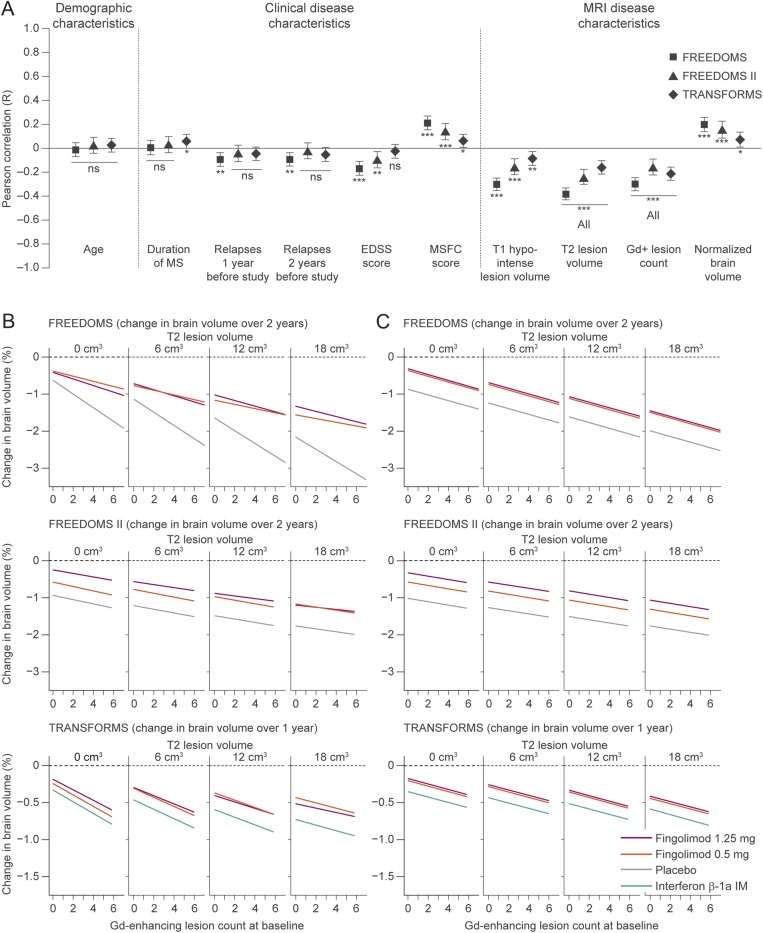

The risk of BVL during all studies increased with increased Gd-enhancing lesion count, T2 lesion volume, T1-hypointense lesion volume, or decreased NBV at baseline (figure 2A). Although correlations were weaker than for MRI measures, patients with higher baseline EDSS and MSFC scores also tended to have greater BVL on-study than those less affected by their disease. Demographic features (e.g., age and sex) did not predict PBVC on-study.

Figure 2. Baseline predictors of on-study PBVC and the effect of treatment.

(A) Pearson correlations between PBVC from baseline to end of study, and candidate baseline predictive variables are shown ± 95% confidence intervals; values are given in table e-2. The correlation between PBVC and MSFC score is positive, because MSFC score decreases as disability increases. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05. (B) Plots by treatment, of the fitted model of the association between PBVC from baseline to end of study, baseline T2 lesion volume, and baseline Gd-enhancing lesion count, including all possible 2-way parameter interactions. Estimates are from an analysis of covariance model with PBVC from baseline to end of study as the response variable, treatment as a factor, and Gd-enhancing lesion count and T2 lesion volume as continuous predictors. Ranges for T2 lesion volume and Gd-enhancing lesion count encompass the 90% range of values observed in FREEDOMS, FREEDOMS II, and TRANSFORMS. The statistical model was evaluated using the T2 lesion volumes shown at the top of each panel. (C) The fitted model as shown in panel B, but excluding parameter interactions (final model). EDSS = Expanded Disability Status Scale; Gd+ = gadolinium-enhancing; MS = multiple sclerosis; MSFC = Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite; ns = not significant; PBVC = percentage brain volume change.

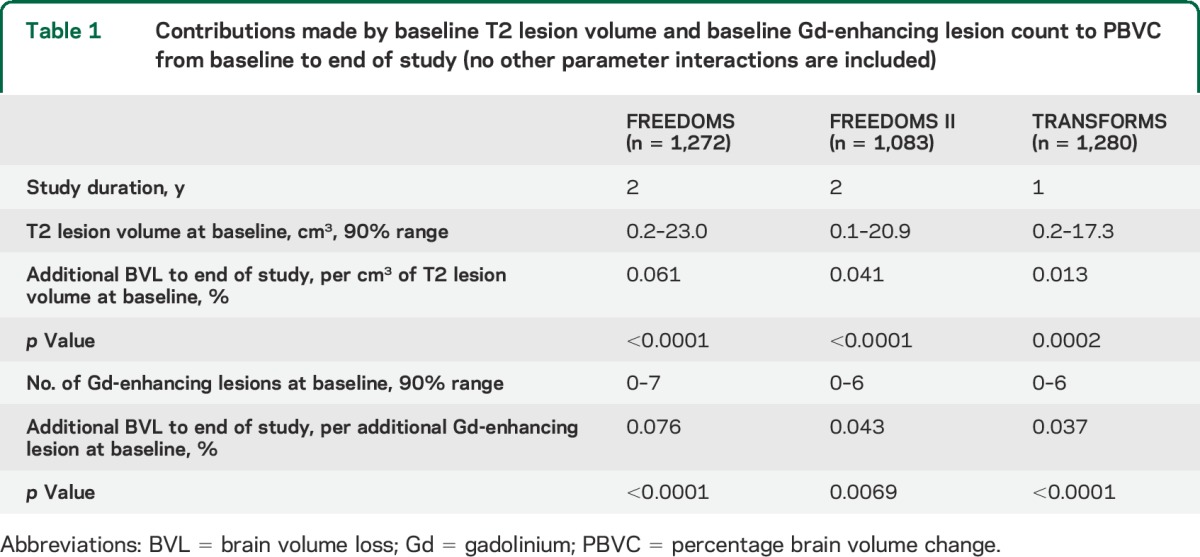

A model selection process identified T2 lesion volume and Gd-enhancing lesion count as the best baseline predictors of PBVC across the 3 studies. A multiple regression analysis of PBVC as a function of these 2 MRI measures and treatment revealed a clear dependency of on-study PBVC on baseline Gd-enhancing lesion count and baseline T2 lesion volume, regardless of whether significant parameter interactions were included (figure 2B) or excluded from the model (figure 2C, table 1). In all treatment arms, patients with a high Gd-enhancing lesion count or high T2 lesion volumes at baseline lost more BV than those with lower lesion burden at baseline.

Table 1.

Contributions made by baseline T2 lesion volume and baseline Gd-enhancing lesion count to PBVC from baseline to end of study (no other parameter interactions are included)

Significant parameter interactions (figure 2B) included Gd-enhancing lesion count with treatment in FREEDOMS (fingolimod and placebo lines diverge as Gd-enhancing lesion count increases), and Gd-enhancing lesion count with T2 lesion volume in TRANSFORMS (line slopes decrease as T2 lesion volume increases). However, these interactions were not seen in all studies, thus they were excluded from the final model. Notably in all studies, for all observed baseline values of Gd-enhancing lesion counts and T2 lesion volume, and regardless of whether interaction terms were included (figure 2B) or excluded (figure 2C), there was less BVL with fingolimod than with placebo or IFNβ-1a IM.

Together, treatment, baseline T2 lesion volume, and baseline Gd-enhancing lesion count explained 47.9% (R, 0.69) and 37.6% (R, 0.61) of the total variability between individual patients in PBVC over 2 years in FREEDOMS and FREEDOMS II, respectively, and 26.9% (R, 0.52) in TRANSFORMS (p < 0.0001, all studies; table 1). Sex was tested but not selected as a covariate by the model selection process in any of the 3 studies; men and women seemed to be equally affected by BVL.

Longitudinal correlations on-study.

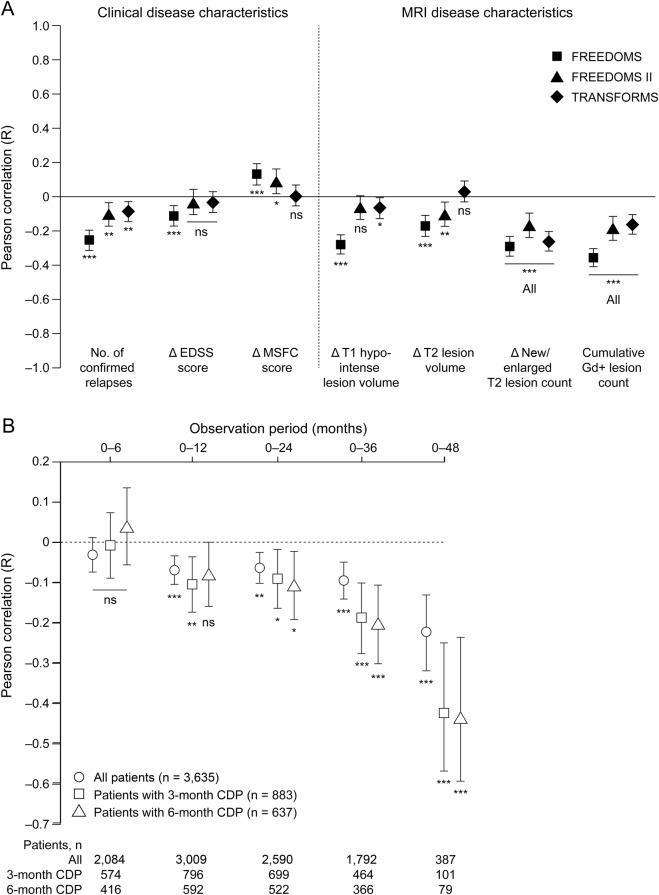

On-study, the magnitude of PBVC correlated with the cumulative number of Gd-enhancing lesions, the number of new or newly enlarged T2 lesions, and the number of confirmed relapses (figure 3A). There was also evidence of a correlation with disability measures in the 2-year FREEDOMS and FREEDOMS II studies, but not in the 1-year TRANSFORMS study.

Figure 3. Concurrent changes in PBVC and clinical and MRI disease characteristics.

(A) Pearson correlations between PBVC from baseline to study end and concurrent changes in clinical and MRI disease characteristics are shown ± 95% confidence intervals; values are given in table e-3. The correlation between PBVC and MSFC score is positive, because MSFC score decreases as disability increases. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05. (B) Pearson correlation between PBVC and observed change over time in EDSS score in the combined core intent-to-treat populations of FREEDOMS, FREEDOMS II, TRANSFORMS, and their extensions, and in the subgroups of patients with 3- and 6-month CDP. Correlation coefficients are shown ± 95% confidence intervals. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. CDP = confirmed disability progression; EDSS = Expanded Disability Status Scale; Gd+ = gadolinium-enhancing; MSFC = Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite; ns = not significant; PBVC = percentage brain volume change.

In the combined analysis population, a significant correlation was seen after 1 year between the magnitude of PBVC and change in EDSS score from baseline, and this correlation strengthened when longer time intervals were analyzed (figure 3B). The same trend was also seen in the subgroups of patients with 3- or 6-month CDP within the combined analysis population.

On-study CDP and PBVC.

When patients in the combined analysis population were grouped by the magnitude of their PBVC (either by category or by quartile), rates of 3- and 6-month CDP and mean EDSS score increased as BVL increased (table 2). This trend was evident at both 2 and 4 years after enrollment.

Table 2.

Patients with 3- or 6-month CDP and mean change in EDSS score by category of BVL, in the combined core intent-to-treat populations of FREEDOMS, FREEDOMS II, TRANSFORMS, and their extensions

DISCUSSION

We have identified baseline clinical and MRI parameters that correlate with NBV. Some parameters reflect structural and functional disease burden accumulated before study enrollment, and some reflect current inflammatory activity. We have also identified baseline parameters that predict BVL over 1 to 2 years, and changes in parameters that correlate longitudinally with concurrent changes in BV on-study. In addition, we observed that the correlation between BVL and CDP strengthens with duration of observation.

Consistent with other reports, baseline NBV decreased as accumulated MRI lesion burden, age, duration of disease, and disability levels increased.24–27 Together, these measures reflect disease severity; older patients with more advanced disease have smaller NBV than younger, less affected patients. Adjusting for age showed that MS disease characteristics are important independent contributors to BVL. This supports the premise that BVL reflects both disease severity and progression. Of note, after adjusting for age, T2 lesion burden, and disability level, duration of disease correlated with NBV, suggesting that some aspect of accumulated CNS damage in MS is not tracked by these other measures. Furthermore, inflammatory lesion activity (Gd-enhancing lesion count), burden of disease (T2 and T1-hypointense lesion volume), and disability were all individually predictive of BVL over 1 to 2 years. Therefore, patients with active disease and/or greater accumulated disease burden at baseline were at greater risk of BVL in the short to medium term than individuals without these characteristics. Together, these findings suggest that the extent of prior disease influences both current BV and future BVL.

The finding that T2 lesion volume and Gd-enhancing lesion count were the best baseline predictors of subsequent BVL is consistent with previous reports.10,28 Correlations between baseline MRI measures and subsequent BVL were somewhat stronger in FREEDOMS than in FREEDOMS II or TRANSFORMS. This may be partly attributable to “noise” from short-term variability in BV or EDSS score, which will have more impact on the strength of correlations in a 1-year study such as TRANSFORMS than in the 2-year FREEDOMS trials. Furthermore, patients receiving IFNβ-1a IM in TRANSFORMS may have a different disease trajectory compared with those receiving placebo in the FREEDOMS studies, even though BVL was greater in all comparator patients than in those receiving fingolimod. This difference may weaken correlations between BVL and factors such as disability progression or lesion activity, which are affected by IFNβ-1a IM.

Individually, baseline T1-hypointense lesion volume correlated with NBV and was predictive of BVL, but was not identified as an important variable by multiple regression analysis. This phenomenon is caused by association between 2 or more exploratory candidate variables.29 Baseline T1-hypointense lesion volume and T2 lesion volume are interdependent, so including both parameters in a multiple regression model is of limited value. In all 3 studies, and as shown by others,10 baseline T2 volume was consistently a better predictor of on-study PBVC than T1-hypointense lesion volume. This enhanced predictive value of T2 lesion volume could mean that it reflects more recent activity than T1-hypointense lesions and thus (as with Gd-enhancing lesions) the likelihood of further disease activity.

Across clinical studies, fingolimod has been shown to be associated with early and consistent reduction in BVL, compared with both placebo and IFNβ-1a IM.14–16 Adjusting for treatment and the 2 strongest predictors of PBVC, multiple regression analysis showed a beneficial treatment effect of fingolimod across the observed ranges of Gd-enhancing lesion counts and T2 lesion volumes in all 3 studies. Such prognostic indicators of future BVL may help to identify those patients at highest risk of excessive brain atrophy and inform clinical decisions regarding treatment.

Despite the correlations between MRI lesions and BVL, lesions explained only a portion of the variance in BV change. Diffuse damage in normal-appearing white and gray matter, and focal demyelination in gray matter, which is not visualized by conventional imaging, is known to occur in MS and has been shown to correlate with disability status.13,30 Direct measurements of diffuse damage cannot readily be made during phase 3 trials, but it may account for some of the unexplained variance in PBVC.

Longitudinal analyses revealed that patients with the most BVL were those with the most pronounced MRI and clinical activity during the observation period. Disability progression was confirmed in a greater proportion of patients with high levels of BVL than in those with lower levels. This supports a previous study, which determined the correlation between brain parenchymal fraction and EDSS score over a 2-year period in patients with RRMS registering disability progression.10 In another study of the same group, patients with MS whose MSFC scores worsened had an approximate mean brain parenchymal fraction change of −0.4% per year, compared with −0.2% per year in patients whose MSFC scores were unchanged.31

The weaker correlation between BVL and disability in the short term compared with the longer term may arise because EDSS scores change slowly.32 The strongest correlation with disability was seen with NBV at baseline, consistent with the time-dependent strengthening of the correlation between BVL and disability on-study. BVL occurs more rapidly in patients with MS than in healthy individuals,2,33 so NBV offers an indication of BVL accrued since symptoms of MS first appeared, a period on average of 7 to 11 years in the populations examined here.14–16

These analyses are based on an RRMS population, so relationships between BV and other factors reported here cannot be inferred in, for example, progressive forms of MS. To mitigate sources of bias in these analyses, candidate variables were selected before performing correlation analyses, and candidate selection was hypothesis-driven based on the results of previous studies. Modeling followed a statistical model selection process and results were reported comprehensively to avoid a reporting bias. Overfitting and overinterpretation were minimized by focusing on patterns common to all studies, rather than on maximizing the explained variance in individual studies.

These analyses provide evidence linking MRI and clinical disease activity with concomitant BVL in the short term, and evidence for the correlation of BVL with worsening disability over longer periods. Given that both focal and diffuse pathologies contribute to disease progression in MS and that the data presented are indicative of an association between BVL and worse outcomes, these findings lend weight to the importance of BVL as a measure of disease progression in MS and to the relevance of potential BVL when making treatment decisions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Professor Richard Rudick for critical review of the manuscript.

GLOSSARY

- BV

brain volume

- BVL

brain volume loss

- CDP

confirmed disability progression

- CI

confidence interval

- EDSS

Expanded Disability Status Scale

- FREEDOMS

FTY720 Research Evaluating Effects of Daily Oral Therapy in MS

- Gd

gadolinium

- IFNβ-1a

interferon β-1a

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- MSFC

Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite

- NBV

normalized brain volume

- PBVC

percentage brain volume change

- RRMS

relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis

- SIENA

structural image evaluation using normalization of atrophy

- SIENAX

structural image evaluation using normalization of atrophy, cross-sectional

- TRANSFORMS

Trial Assessing Injectable Interferon vs FTY720 Oral in RRMS

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Professor Radue was involved in the design and conceptualization of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafting and revising the manuscript. Professor Barkhof was involved in the design and conceptualization of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafting and revising the manuscript. Professor Kappos was involved in the design and conceptualization of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting and revising the manuscript. Professor Sprenger was involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data, and revising the manuscript. Dr. Häring was involved in the design and conceptualization of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafting and revising the manuscript. Dr. de Vera was involved in the design and conceptualization of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafting and revising the manuscript. Dr. von Rosenstiel was involved in the interpretation of the data and revising the manuscript. Dr. Bright was involved in drafting and revising the manuscript. Dr. Francis was involved in the design and conceptualization of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafting and revising the manuscript. Professor Cohen was involved in the design and conceptualization of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafting and revising the manuscript.

STUDY FUNDING

This analysis was funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland.

DISCLOSURE

E. Radue has received honoraria for serving as speaker at scientific meetings and as a consultant for Bayer Schering, Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, and Novartis. He has received financial support for research activities from Actelion, Basilea Pharmaceutica Ltd., Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, and Novartis. F. Barkhof has received consulting or speaking fees from Biogen Idec, Bayer Schering Pharma, Genzyme, Jansen Alzheimer Immunotherapy, Lundbeck, MediciNova, Merck Serono, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Synthon, and Teva. L. Kappos' institution (University Hospital Basel) received in the last 3 years and used exclusively for research support: steering committee, advisory board, and consultancy fees from Actelion, Addex, Bayer HealthCare, Biogen, Biotica, Genzyme, Lilly, Merck, Mitsubishi, Novartis, Ono Pharma, Pfizer, Receptos, Sanofi-Aventis, Santhera, Siemens, Teva, UCB, XenoPort; speaker fees from Bayer HealthCare, Biogen, Merck, Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis, Teva; support of educational activities from Bayer HealthCare, Biogen, CSL Behring, Genzyme, Merck, Novartis, Sanofi, Teva; royalties from Neurostatus Systems GmbH; grants from Bayer HealthCare, Biogen, Merck, Novartis, Roche, Swiss MS Society, the Swiss National Research Foundation, the European Union, and Roche Research Foundations. T. Sprenger has received no personal compensation for consultancy activities. His employer, the University Hospital Basel, has received compensation for his serving on scientific advisory boards or for speaking fees, from Actelion, ATI, Biogen Idec, ElectroCore, Genzyme, Jansen, Mitsubishi Pharma Europe, Novartis, and Teva. D. Häring is an employee of Novartis Pharma AG. A. de Vera is an employee of Novartis Pharma AG. P. von Rosenstiel is an employee of Novartis Pharma AG. J. Bright is an employee of Oxford PharmaGenesis Ltd., funded by Novartis Pharma AG. G. Francis is an employee of Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. J. Cohen has received consultancy fees from EMD Serono, Genzyme, Innate Immunotherapeutics, and Novartis. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bermel RA, Bakshi R. The measurement and clinical relevance of brain atrophy in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2006;5:158–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Stefano N, Giorgio A, Battaglini M, et al. Assessing brain atrophy rates in a large population of untreated multiple sclerosis subtypes. Neurology 2010;74:1868–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zivadinov R, Bergsland N, Dolezal O, et al. Evolution of cortical and thalamus atrophy and disability progression in early relapsing-remitting MS during 5 years. Am J Neuroradiol 2013;34:1931–1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox NC, Jenkins R, Leary SM, et al. Progressive cerebral atrophy in MS: a serial study using registered, volumetric MRI. Neurology 2000;54:807–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudick RA, Fisher E, Lee JC, Simon J, Jacobs L. Use of the brain parenchymal fraction to measure whole brain atrophy in relapsing-remitting MS. Multiple Sclerosis Collaborative Research Group. Neurology 1999;53:1698–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fotenos AF, Mintun MA, Snyder AZ, Morris JC, Buckner RL. Brain volume decline in aging: evidence for a relation between socioeconomic status, preclinical Alzheimer disease, and reserve. Arch Neurol 2008;65:113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobsen C, Hagemeier J, Myhr KM, et al. Brain atrophy and disability progression in multiple sclerosis patients: a 10-year follow-up study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014;85:1109–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller DH, Barkhof F, Frank JA, Parker GJ, Thompson AJ. Measurement of atrophy in multiple sclerosis: pathological basis, methodological aspects and clinical relevance. Brain 2002;125:1676–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zivadinov R, Bakshi R. Central nervous system atrophy and clinical status in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimaging 2004;14:27S–35S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher E, Rudick RA, Simon JH, et al. Eight-year follow-up study of brain atrophy in patients with MS. Neurology 2002;59:1412–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sormani MP, Arnold DL, De Stefano N. Treatment effect on brain atrophy correlates with treatment effect on disability in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2014;75:43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudick RA, Fisher E. Preventing brain atrophy should be the gold standard of effective therapy in MS (after the first year of treatment): yes. Mult Scler 2013;19:1003–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Filippi M, Rocca MA, Barkhof F, et al. Association between pathological and MRI findings in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:349–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kappos L, Radue EW, O'Connor P, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:387–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calabresi PA, Radue EW, Goodin D, et al. Efficacy and safety of fingolimod in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: results from the 24-month phase 3 double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study (FREEDOMS II). Lancet Neurol 2014;13:545–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen JA, Barkhof F, Comi G, et al. Oral fingolimod or intramuscular interferon for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:402–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khatri B, Barkhof F, Comi G, et al. Comparison of fingolimod with interferon beta-1a in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a randomised extension of the TRANSFORMS Study. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:520–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kappos L, Radue EW, O'Connor P, et al. Switching therapy to fingolimod improves clinical and MRI outcomes: subgroup analysis from the fingolimod phase III FREEDOMS extension (up to 4 years) study. Mult Scler 2013;19(11 suppl):74–558 P619. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reder AT, Jeffery D, Goodin D, et al. Long-term efficacy of fingolimod in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: results from the phase 3 FREEDOMS II extension study. Mult Scler 2013;19(11 suppl):74–558 P1092. [Google Scholar]

- 20.International Conference on Harmonisation. International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use: ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. Guideline for Good Clinical Practice. Available at: http://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Efficacy/E6/E6_R1_Guideline.pdf. Accessed January 17, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Available at: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html. Accessed January 17, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith SM, Zhang Y, Jenkinson M, et al. Accurate, robust, and automated longitudinal and cross-sectional brain change analysis. Neuroimage 2002;17:479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barkhof F, de Jong R, Sfikas N, et al. The influence of patient demographics, disease characteristics and treatment on brain volume loss in Trial Assessing Injectable Interferon vs FTY720 Oral in Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis (TRANSFORMS), a phase 3 study of fingolimod in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2014;20:1704–1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chard DT, Griffin CM, Parker GJ, Kapoor R, Thompson AJ, Miller DH. Brain atrophy in clinically early relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Brain 2002;125:327–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roosendaal SD, Bendfeldt K, Vrenken H, et al. Grey matter volume in a large cohort of MS patients: relation to MRI parameters and disability. Mult Scler 2011;17:1098–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanfilipo MP, Benedict RH, Sharma J, Weinstock-Guttman B, Bakshi R. The relationship between whole brain volume and disability in multiple sclerosis: a comparison of normalized gray vs. white matter with misclassification correction. Neuroimage 2005;26:1068–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Stefano N, Matthews PM, Filippi M, et al. Evidence of early cortical atrophy in MS: relevance to white matter changes and disability. Neurology 2003;60:1157–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paolillo A, Piattella MC, Pantano P, et al. The relationship between inflammation and atrophy in clinically isolated syndromes suggestive of multiple sclerosis: a monthly MRI study after triple-dose gadolinium-DTPA. J Neurol 2004;251:432–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chatterjee S, Hadi AS. Regression Analysis by Example, 4th ed Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitzler HH, Su J, Zeineh M, et al. Deficient MWF mapping in multiple sclerosis using 3D whole-brain multi-component relaxation MRI. Neuroimage 2012;59:2670–2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rudick RA, Lee JC, Nakamura K, Fisher E. Gray matter atrophy correlates with MS disability progression measured with MSFC but not EDSS. J Neurol Sci 2009;282:106–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tremlett H, Paty D, Devonshire V. Disability progression in multiple sclerosis is slower than previously reported. Neurology 2006;66:172–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Stefano N, Airas L, Grigoriadis N, et al. Clinical relevance of brain volume measures in multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs 2014;28:147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.