Abstract

[Purpose] The aim of this study was to determine the effects of Thai massage on physical fitness in soccer players. [Subjects and Methods] Thirty-four soccer players were randomly assigned to receive either rest (the control group) or three 30-minute sessions of Thai massage over a period of 10 days. Seven physical fitness tests consisting of sit and reach, hand grip strength, 40 yards technical agility, 50-meter sprint, sit-ups, push-ups, and VO2, max were measured before and after Thai massage or rest. [Results] All the physical fitness tests were significantly improved after a single session of Thai massage, whereas only the sit and reach, and the sit-ups tests were improved in the control group. [Conclusion] Thai massage could provide an improvement in physical performance in soccer players.

Key words: Thai massage, Physical fitness, Soccer players

INTRODUCTION

Massage is frequently used as warm-up and recovery techniques in sports competitions for athletes. It can provide several physiological and neuromuscular benefits to the body such as an increase in blood flow, a reduction in muscle tension and neurological excitability, a decrease in muscle soreness, an increase in flexibility, and an increase in a sense of well-being1). Gentle mechanical pressure provided by massage can change neural excitability as characterized by a reduced amplitude of H-reflex2). It was also found to increase parasympathetic activity3), reduce stress hormonal levels4), increase muscle compliance and range of joint motion5), decrease passive stiffness6) and active stiffness5), increase the arteriolar pressure and muscle temperature by rubbing, which helps to increase blood flow7), and decrease anxiety and improve in mood state after massage-facilitated relaxation8). These benefits of the massage were suggested to help athletes to enhance physical performance and reduce the risk of injury during competition1). Thai massage is well recognized and used to enhance physical fitness for soccer players in Thailand. However, there is little scientific evidence to support the suggestion that massage could enhance physical fitness in any sports. Since soccer is one of the contact sports that requires players to have a variety of physical fitness levels during competitions, we decided to investigate the acute effects of Thai massage on physical fitness in soccer players.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

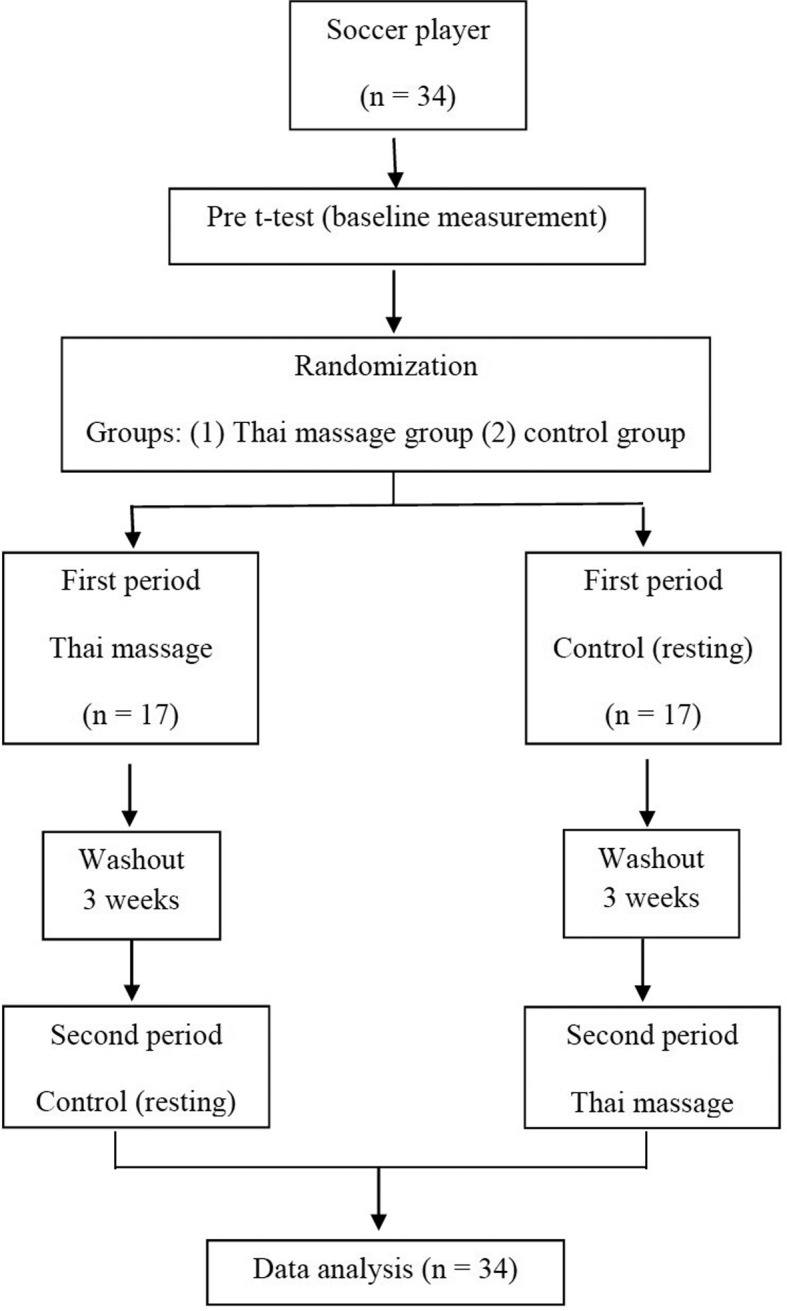

A 10-day crossover design was used in the present study. The Ethics Committee of Khon Kaen University approved the research protocol with the criteria based on the Declaration of Helsinki and good clinical practices (ICH GCP) (No. HE562078). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects at the beginning of the study. The study was conducted in the 34 soccer players from Nakhon Phanom Province, Thailand. The players were randomly allocated to either the Thai massage (TM) group or the control (resting) group using a simple randomized allocation. This was followed by a 3-week washout period, after which each subject was crossover assigned to the other group. A summary of the study design, subject recruitment, and participation is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of study design and participants

Thirty-four soccer players (age, 26.02 ± 3.89 years; body mass, 66.74 ± 7.09 kg, height, 174.03 ± 4.33 cm; BMI, 22.00 ± 1.79 kg/m2) from Division 2 of the Football Association of Thailand under the Patronage of His majesty the King were recruited to participate in the study. All participants provided written informed consent prior to the study. Any of the subjects who had the following precautions for Thai massage were excluded: fever with a body temperature over 38.5 °C, uncontrolled hypertension, hypersensitivity to pain, fracture, and joint dislocation.

Whole body Thai massage was applied to each of the subjects in the massage group for 30 minutes at 25 °C. Three sessions of massage, which mainly covered 4 body parts, the shoulder (5 minutes), back (5 minutes), arms (10 minutes), and legs (10 minutes), were applied (once every 3 days) within a period of 10 days. The massage was given by two certified traditional Thai massage therapists who had two or more years of experience and were tested for quality of Thai massage skills prior to the study.

The subjects in the control group were instructed to rest for the same period of time in the same laboratory room as those for the treatment group. They had three 30-minute rest sessions (once every 3 days) over a period of 10 days.

Seven physical fitness tests, including the sit and reach (flexibility), handgrip (strength), 40 yards technical (agility), 50-meter sprint (speed), sit-ups, push-ups (muscles endurance), and VO2, max tests were performed before and after the 3 sessions of Thai massage.

The sit and reach test9) was chosen to determine the flexibility of the hamstring and back muscles. The subjects sat on the floor with the knees fully extended and reached forward as much as possible on a sit and reach box. Each of them performed the test twice, and the best one was recorded. The handgrip test10, 11) was used to measure hand and forearm muscular strength by using a digital dynamometer. Subjects performed the test twice (alternately with both hands) with a 1-minute rest period between measures. The best score of the two trials for each hand was chosen. The sit-ups test was performed to measure the strength and endurance of the abdominals and hip flexor muscles. The subjects were instructed to perform as many bent knee sit-ups as possible within 60 seconds. The push-ups test was chosen to measure the strength and endurance of the upper body muscles. This test was performed with the subjects in the prone position, with the forefoot or toes on the floor, hips and knees straight, and the elbows fully extended while placing the body weight on both hands. The subjects bent their elbows until their chest was just about to touch the floor and then fully extended them again. They performed as many push-ups as possible within 1 minute. The 40 yards technical test was chosen for determination of the agility of the subjects. The 50-meters sprint test involved running a single maximum sprint over 50 meters, with the time recorded. It reflected the speed of the subjects. VO2, max was measured by using a cycle ergometer according to the Astrand-Rhyming protocol test12). After being informed about the procedures and precautions of the test, the subjects were fitted with a Polar heart rate monitor and performed 5 minutes of stretching exercises for their knee flexor, knee extensor, and ankle dorsiflexor muscles. The test began by having the subjects sit on a cycle ergometer with an appropriate (at the hip level in straight standing) seat height. They performed cycling exercise for one minute without load following the tick of a metronome set at a speed of 50 rpm (or 18 km/h). After that, the load was adjusted from 1–1.5 kp to achieve a heart rate response of around 120 bpm. The load could be gradually increased in increments of 0.5 kp every minute if the heart rate did not reach 120 bpm until 6 minutes of exercise.

One of the coauthors (Uraiwan Chatchawan) with expertise in epidemiology and biostatistics analyzed the data and was completely blinded to the patients’ group assignments. All analyses were performed on the basis of the intention-to-treat principle. All outcome measures are presented as means ± standard deviations (SD). The independent samples t-test was used for comparisons between the groups, and the dependent samples t-test was used for comparisons between before and after the intervention. Interaction effects were assessed by the ordinary least squares (OLS) method13). We used a cross analysis (Student’s t-test) to compare the mean change in score (post–pre) because the primary outcomes (VO2, max) was normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk W test; p>0.05)14, 15). In case of significant period × treatment interaction, the second-period data were not used for the analysis16).

RESULTS

All of the physical fitness tests showed significant improvements after a single session of Thai massage (Table 1), whereas only the sit and reach, and sit-ups tests showed improvements in the control group. Analysis of the period effect and carry over effect revealed that the first tests of VO2, max, handgrip strength, 40 yards technical test did not affect the test in the second sequence (Table 1).

Table 1. Physical fitness parameters (mean ± SD) of the Thai massage (TM) and control groups.

| Parameters | Sequence I (A-B) | Sequence II (B-A) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TM | Control | Control | TM | |||||

| Pre/Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post |

| VO2, max (ml/kg/min) | 42.14 ± 5.32 | 45.30 ± 6.72* | 42.64 ± 5.25 | 42.21 ± 5.57 | 42.54 ± 7.51 | 41.75 ± 8.15 | 42.13± 7.68 | 43.77±8.74* |

| Push-ups# (number/min) | 37.94 ± 8.77 | 40.05 ± 8.50* | 37.29 ± 8.87 | 37.47 ± 9.02 | 33.88 ± 9.63 | 33.88 ±10.11 | 34.29 ± 9.71 | 35.70±10.89* |

| Sit-ups# (number /30 sec) | 26.70 ± 4.38 | 28.58 ± 4.35* | 26.23 ± 4.67 | 26.76 ± 4.35 | 27.58 ± 3.14 | 28.23 ±3.25* | 28.17 ± 3.35 | 29.23 ± 3.73* |

| 50-meter speed# (sec) | 6.98 ± 0.35 | 6.74 ± 0.45* | 7.13 ± 0.36 | 7.14 ± 0.34 | 7.47 ± 0.52 | 7.53 ±0.82 | 7.17 ± 0.43 | 7.14 ± 0.37* |

| Grip strength (kg/BW) | 0.70 ± 0.09 | 0.75 ± 0.09* | 0.69 ± 0.08 | 0.68 ± 0.09 | 0.71 ± 0.10 | 0.72 ±0.09 | 0.71 ± 0.09 | 0.74 ± 0.10* |

| 40 yards technical test (sec) | 10.86 ± 0.84 | 10.22 ± 0.83* | 10.92 ± 0.75 | 10.86 ± 0.65 | 11.09 ± 0.67 | 11.05 ±0.67 | 11.05 ± 0.81 | 10.68 ± 0.61* |

| Sit and reach# (cm) | 21.45 ± 5.50 | 23.06 ± 5.20* | 20.90 ± 5.41 | 20.57 ± 6.02 | 18.83 ± 5.11 | 19.47 ±4.74* | 19.28 ± 5.04 | 20.80 ± 5.04* |

# Carryover effect on significance (p < 0.05). * Significant improved when compared with the pre-test value (p < 0.05)

However, when the mean changes for all outcome measures were compared between the two groups, we found no significant difference (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of the mean change scores (pre–post) of physical fitness tests between the Thai massage (TM) and control groups.

| Parameters | TM=A | Control=B | Different (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| VO2, max (ml/kg/min) (n = 34) | 1.19 ± 2.86 | 0.61 ± 2.25 | −0.58 (−0.36 to 1.53) |

| Grip strength (kg./BW) (n = 34) | 0.03 ± 0.04 | 0.004 ± 0.01 | −0.03 (−0.04 to −0.01) |

| 40 yards technical test (sec) (n = 34) | −0.34 ± 0.58 | −0.22 ± 0.50 | 0.12 (−0.07 to 0.32) |

| Push-ups (number/min) (n = 17) | 2.11 ± 2.18 | 1.41 ± 1.58 | −0.70 (−2.03 to 0.62) |

| Sit-ups (number/30 sec) (n = 17) | 1.88 ± 2.17 | 1.06 ± 1.19 | −0.82 (−2.05 to 0.40) |

| 50-meter speed (sec) (n = 17) | −0.23 ± 0.36 | 0.02 ± 0.31 | 0.21 (−0.02 to 0.44) |

| Sit and reach (cm) (n = 17) | 1.61 ± 1.65 | 1.51 ± 1.43 | −0.1 (−1.17 to 0.98) |

DISCUSSION

This study showed that a single session of Thai massage could likely provide improvements in physical fitness and flexibility in soccer players. This could be due to Thai massage reducing muscle tension and increasing blood flow17, 18). In line with our results, a previous study showed that massage associated with myofascial trigger points increased the body flexibility in patients with back pain19). The potential mechanisms of Thai Massage are probably stimulation of proprioceptors of muscles and enhancement of the reducing in muscle spasm and adhesion in the tissues being massaged19). Thai massage using deeper pressure followed by passive stretching is applied along the massage area, which covers all muscles having myofascial trigger points (MTrPs). Thai massage has effects that breakdown any MTrPs adhesions. Since Thai Massage has been found to cause an increase in muscle blood supply, it may allow the muscles to get more oxygen from the blood and provide sufficient nutrients to the muscles. It causes the muscle to have more endurance as well as strength20). The effects of Thai massage on increasing agility and sprint speed in soccer players may be explained by the stimulation of heart rate variability resulting from the massage21). Effleurage massage also increases agility22) and shuttle run times in female basketball players23). In addition, Thai massage may provide some psychological benefits that promote recovery. Massage is known to enhance the positive mood states and psychological well-being24, 25). In the current study, the players who received a massage could sleep well and recover from fatigue quickly. On the day after a massage, most of the players felt very fresh and did well on agility and sprint tests. Thus, Thai massage could be used as a recovery technique for athletes.

The limitation of having large standard deviations as compared with the corresponding means resulted in there being no significant differences in comparisons between the two groups (Table 2). Therefore, further study, a longer period of investigation such as 20 days is suggested to confirm these short-term effects in soccer players. Thai massage may have a modest effect that help to improve the parameters of physical fitness examined in this study, in the same way as other types of massage used to aid physical performance prior to exercise. This can be seen in Table 2, which shows that the means for all the parameters of the Thai massage group were a little higher than those of the control group.

Based on the results of our study, we conclude that Thai Massage may provide some beneficial effects on physical fitness in soccer players, especially for VO2max, and may facilitate muscle strength, agility, and speed. Further research is needed to verify these effects in a different population in sports.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the subjects who participated in this study. The study was supported by the Research and Training Center for Enhancing Quality of Life of Working-Age People at Khon Kaen University. We also thank the Exercise and Sport Sciences Development and Research Group for providing some tools for data collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cafarelli E, Flint F: The role of massage in preparation for and recovery from exercise. An overview. Sports Med, 1992, 14: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morelli M, Seaborne DE, Sullivan SJ: Changes in h-reflex amplitude during massage of triceps surae in healthy subjects. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 1990, 12: 55–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delaney JP, Leong KS, Watkins A, et al. : The short-term effects of myofascial trigger point massage therapy on cardiac autonomic tone in healthy subjects. J Adv Nurs, 2002, 37: 364–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hernandez-Reif M, Field T, Krasnegor J, et al. : Lower back pain is reduced and range of motion increased after massage therapy. Int J Neurosci, 2001, 106: 131–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNair PJ, Stanley SN: Effect of passive stretching and jogging on the series elastic muscle stiffness and range of motion of the ankle joint. Br J Sports Med, 1996, 30: 313–317, discussion 318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stanley S, Purdam C, Bond T, et al. : Passive tension and stiffness properties of the ankle plantar flexors: the effects of massage. Paper presented at the XVIIIth Congress of the International Society of Biomechanics, Zurich, 2001.

- 7.Drust B, Atkinson G, Gregson W, et al. : The effects of massage on intra muscular temperature in the vastus lateralis in humans. Int J Sports Med, 2003, 24: 395–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF: Profile of Mood State manual. San Diego: Educational and Industrial Testing Service, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kubo A, Murata S, Otao H, et al. : Study of musculoskeletal ambulation disability symptom complex (MADS) in elderly community residents: a comparison of physical function between the elderly with and without potential MADS. J Phys Ther Sci, 2012, 24: 201–204. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirao A, Murata S, Murata J, et al. : Relationships between the occlusal force and physical/cognitive functions of elderly Females living in the community. J Phys Ther Sci, 2014, 26: 1279–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kin S, Li S: Effects of Taijiquan on the physical fitness of elderly Chinese people. J Phys Ther Sci, 2006, 18: 133–136. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoeger WW, Hoeger SA: Principles and labs for fitness and wellness, 6th ed. Belmont, Wadsworth, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kenward MG, Jones B: The analysis of data from 2 x 2 cross-over trials with baseline measurements. Stat Med, 1987, 6: 911–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altman DG: Practical Statistics for Medical Research. London: Chapman and Hall, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Senn S: Cross-Over Trials in Clinical Research, 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grizzle JE: The two-period change-over design and its use in clinical trials. Biometrics, 1965, 21: 467–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eungpinichpong W, Kongnaka T: Effects of femoral artery temporarily occlusion on skin blood flow of foot. J Med Tech Phy Ther, 2002, 14: 151–159. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peungsuwan P, Sermcheep P, Harnmontree P, et al. : The Effectiveness of Thai exercise with traditional massage on the pain, walking ability and QOL of older people with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial in the community. J Phys Ther Sci, 2014, 26: 139–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chatchawan U, Eungpinichpong W, Sooktho S, et al. : Effects of Thai traditional massage on pressure pain threshold and headache intensity in patients with chronic tension-type and migraine headaches. J Altern Complement Med, 2014, 20: 486–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leelayuwat N, Eungpinichpong W, Manimmanakom A: The effects of Thai massage on resistance to fatigue of back muscles in chronic low back pain patients. J Med Tech Phy Ther, 2001, 13: 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eungpinichpong W: Therapeutic Thai Massage. Bangkok: Chonromdek Publishing House, 2008, pp 54–58. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leivadi S, Hernandez-Reif M, Field TO, et al. : Massage therapy and relaxation effects on university dance students. J Dance Med Sci, 1999, 3: 108–112. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hilbert JE, Sforzo GA, Swensen T: The effects of massage on delayed onset muscle soreness. Br J Sports Med, 2003, 37: 72–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKechnie AA, Wilson F, Watson N, et al. : Anxiety states: a preliminary report on the value of connective tissue massage. J Psychosom Res, 1983, 27: 125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weinberg R, Jackson A, Kolodny K: The relationship of massage and exercise to mood enhancement. Sport Psychol, 1988, 2: 202–211. [Google Scholar]