Abstract

Preliminary results demonstrated that concurrent sunitinib and stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) is an active regimen for metastases limited in number and extent. This analysis was conducted to determine the long-term survival and cancer control outcomes for this novel regimen. Forty-six patients with oligometastases, defined as five or fewer clinical detectable metastases from any primary site, were treated on a phase I/II trial from February 2007 to September 2010. The majority of patients were treated with 37.5 mg sunitinib (days 1–28) and SBRT 50 Gy (days 8–12 and 15–19) and maintenance sunitinib was used in 39 % of patients. Median follow up for surviving patients is 3.6 years. The 4-year estimates for local control, distant control, progression-free and overall survival were 75 %, 40 %, 34 % and 29 %, respectively. At last follow-up, 26 % of patients were alive without evidence of disease, 7 % were alive with distant metastases, 48 % died from distant metastases, 2 % died from local progression, 13 % died from comorbid illness, and 4 % died from treatment-related toxicities. Patients with kidney and prostate primary tumors were associated with a significantly improved overall survival (hazard ratio=0.25, p=0.04). Concurrent sunitinib and SBRT is a promising approach for the treatment of oligometastases and further study of this novel combination is warranted.

Keywords: Sunitinib, Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), Oligometastases, Image-guided radiation therapy, Metastases

Introduction

The majority of patients with distant metastases from solid tumors are treated with systemic therapy alone with local therapy reserved for palliation of local symptoms [1]. Both surgery and stereotactic radiosurgery have been shown to improve local control and overall survival (OS) in patients with single brain metastases compared to palliative whole brain radiotherapy[2, 3]. For selected patients with extracranial oligometastases, defined as metastatic deposits that are limited in number and organ involvement, supplementing systemic therapy with effective local therapy is a rational strategy that is increasingly supported by robust clinical data [4, 5]. Curative intent radiotherapy has been studied for lung, liver, bone and adrenal and lymph node metastases in both site-specific and multi-organ studies using image-guided stereotactic techniques with local control rates ranging from 60 % to 9 % [6–10]. For studies that irradiated all sites of known disease, approximately 15 % to 25 % of patients remain alive and free of recurrence several years after radiation [11, 12]. The primary pattern of failure is distant metastasis outside of the radiation field within months of treatment, which highlights the need for more effective systemic agents to further improve outcomes in patients with oligometastases treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) or other local therapies [7–10].

While integrating systemic therapy with local therapy has been shown to effectively prevent distant metastases in patients with high-risk primary cancers, this paradigm has not been extensively explored in the setting of oligometastases. For instance, in recently published SBRT trials for lung and liver metastases, chemotherapy was discontinued for at least 4 weeks before, during and after radiation [6, 8, 9]. A potential advantage of concurrent systemic therapy and radiation therapy is the concept of spatial cooperation to simultaneously address the competing risks of local and distant progression [13].

Sunitinib, a multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor of VEGFR1, VEGFR2, VEGFR3, PDGFR, c-kit, FLT3 and ret, is a well-studied angiogensis inhibitor with an acceptable single agent toxicity profile [14, 15]. Preclinical data suggests that sunitinib and other angiogenesis inhibitors enhance response to radiotherapy [16, 17]. In addition to effects on angiogenesis, several research groups, including ours, demonstrated robust effects of sunitinib on immune-suppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) [18–20]. We initiated a phase I/II trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of concurrent sunitinib and SBRT for oligometastases. We have previously reported the phase I and preliminary phase II efficacy results [20, 21]. The present study analyzed the survival and tumor control outcomes for the combined cohort of patients treated with concurrent sunitinib and SBRT with additional follow-up.

Methods

Patient eligibility

Between February 2007 and September 2010, 47 patients with one to five radiographically apparent distant metastases were enrolled on either a phase I or phase II single institution clinical trial using sunitinib and SBRT to treated limited oligometastatic disease. The study was approved by the Mount Sinai School of Medicine institutional review board, which was conducted in accordance to federal and institutional guidelines. One patient withdrew prior to starting treatment due to declining performance status and was excluded from analysis. Patients with pathologically confirmed solid tumor malignancy with one to five sites of active metastatic disease on whole body imaging (positron emission tomography [PET] or computed tomography [CT] chest, abdomen, pelvis and bone scans) measuring ≤6 cm were eligible. Other eligibility criteria included age ≥18 years, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0–2, and adequate hematologic, hepatic and renal function. Prior chemotherapy or radiation was allowed but had to be discontinued for at least 2 weeks before study entry. Major exclusion criteria included uncontrolled brain metastases, malignant pleural or pericardial effusion, life expectancy <3 months, prior radiation to targeted area(s) or uncontrolled intercurrent illness. Following a fatal bleeding event occurring in one patient receiving concomitant anticoagulant therapy, the trial was amended to exclude patients with a history of non-inducible bleeding or patients requiring continuation of anticoagulation during study treatment (Fig. 1).

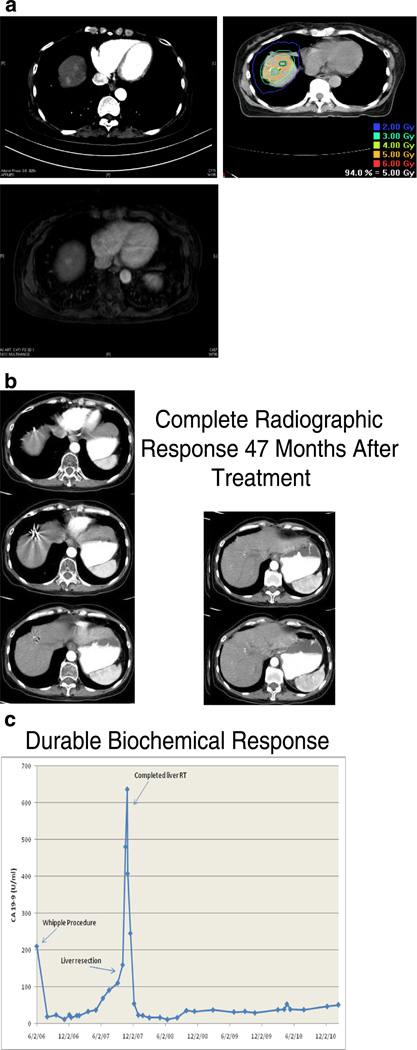

Fig. 1.

Representative patient treated with concurrent sunitinib and IGRT. a Pretreatment arterial phase CT of abdomen demonstrating suspicious lesions, follow-up MR demonstrating two liver metastases in patient with pancreatic cancer. This patient were treated with concurrent sunitinib (50 mg/day; days 1–28) and IGRT (50 Gy; days 8–19) followed by maintenance sunitinib. b The patient showed no evidence of residual disease in the liver and there is no clinical, radiographic or metabolic evidence of distant progression on physical examination, CT and PET at 47 month follow-up. c Durable biochemical response with serial CA 19-9 blood tests

Drug administration

The dose escalation procedure for the phase I trial was described previously [21]. Based on dose-limiting toxicities associated with sunitinib doses of 50 mg daily, the recommended phase II dose was 37.5 mg daily on days 1–28. Sunitinib was administered orally once daily in 6-week cycles consisting of 4 weeks of treatment followed by 2 weeks without treatment. Sunitinib was provided by Pfizer, the sponsor of the trial. As part of the phase I trial, three patients received 25 mg daily and five patients received 50 mg daily (Table 1). The 13 patients on the expanded cohort portion of the phase I trial and all 25 patients on the phase II trial received 37.5 mg daily during radiation (Table 1). After completion of the first treatment cycle, the treating medical oncologist had the option of continuing on maintenance sunitinib for additional cycles if there was no unacceptable toxicity or progression. If patients did not receive maintenance sunitinib, patients generally received alternative chemotherapy, biological therapy or hormonal therapy, unless limited by age or performance status.

Table 1.

Treatment characteristics

| Variable | Number (%) | 4-year overall survival |

|---|---|---|

| Sunitinib dose during stereotactic radiation | p=0.67 | |

| 25 mg | 3 (7 %) | 33 % |

| 37.5 mg | 38 (83 %) | 28 % |

| 50 mg | 5 (11 %) | 40 % |

| IGRT dose | p=0.93 | |

| ≤30 Gy | 2 (4 %) | 0 % |

| 40 Gy | 9 (20 %) | 38 % |

| 50 Gy | 35 (76 %) | 28 % |

| Maintenance sunitinib | p=0.20 | |

| No | 28 (61 %) | 22 % |

| Yes | 18 (39 %) | 42 % |

Radiation guidelines

Radiation was administered concurrently with the first cycle of sunitinib on days 8–12 and 15–19. Each patient's treatment was individualized with respect to immobilization and radiation planning technique to optimally cover the target volume and adequately account for organ motion. In summary, all patients underwent CT simulation with appropriate site-specific immobilization using an Alpha Cradle, a Vac Lock bag or an Aquaplast mask. Since respiratory gating was not available for lung or abdominal tumors, maximum inspiratory, expiratory and free-breathing CT scans were fused to document the maximum amplitude of tumor motion for estimation of an ITV. Relaxed end expiratory breath holding, forced shallow breathing and/or external optical tracking often supplemented with an abdominal belt were utilized for tumors with documented respiratory motion. The GTV was defined as gross tumor on CT, MRI and/or PET. GTV to PTV expansion ranged from 0.5 to 1.5 cm depending on extent of organ motion or proximity to critical structures. The prescribed radiation dose was 40 Gy in ten daily fractions for six patients treated on the phase I trial and was 50 Gy in ten daily fractions for the remaining 15 patients treated on the phase I trial and 25 patients treated on the phase II trial (Table 1). An additional five patients received less than the prescribed dose secondary to acute toxicity or physician discretion. Dose was prescribed to the PTV with >90 % of the target received the prescription dose and a 3D maximum of <110 %. When necessary due to the immediate proximity to critical serial structures (e.g., spinal cord, small bowel, esophagus), normal tissue protection was prioritized above target coverage. Planning constraints on serial and parallel organs at risk were described earlier [21]. Treatment planning consisted of conformal arcs, intensity modulated radiation or three-dimensional forward planning. Daily image guidance using kilovoltage or megavoltage orthogonal X-rays or cone beam CT was mandatory using implanted fiducial markers or bone fusion.

Follow-up and study end points

The primary endpoint of the phase I trial was feasibility and dose-limiting toxicity and the primary end point for the phase II trial was progression-free survival (PFS) as previously described [20–22]. Follow-up visits were planned 1 month after completing RT and every 3 months subsequently for 2 years. Patients were followed up until death and confirmed using the social security death index. Patients underwent diagnostic imaging studies before all follow-up visits after the initial 1-month visit. Toxicity was assessed in patients at regular intervals by using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events criteria (version 3.0). Dose limiting events were defined as any grade 4 or 5 toxicity and non-hematological grade 3 toxicity attributed to radiation or sunitinib.

Statistical considerations

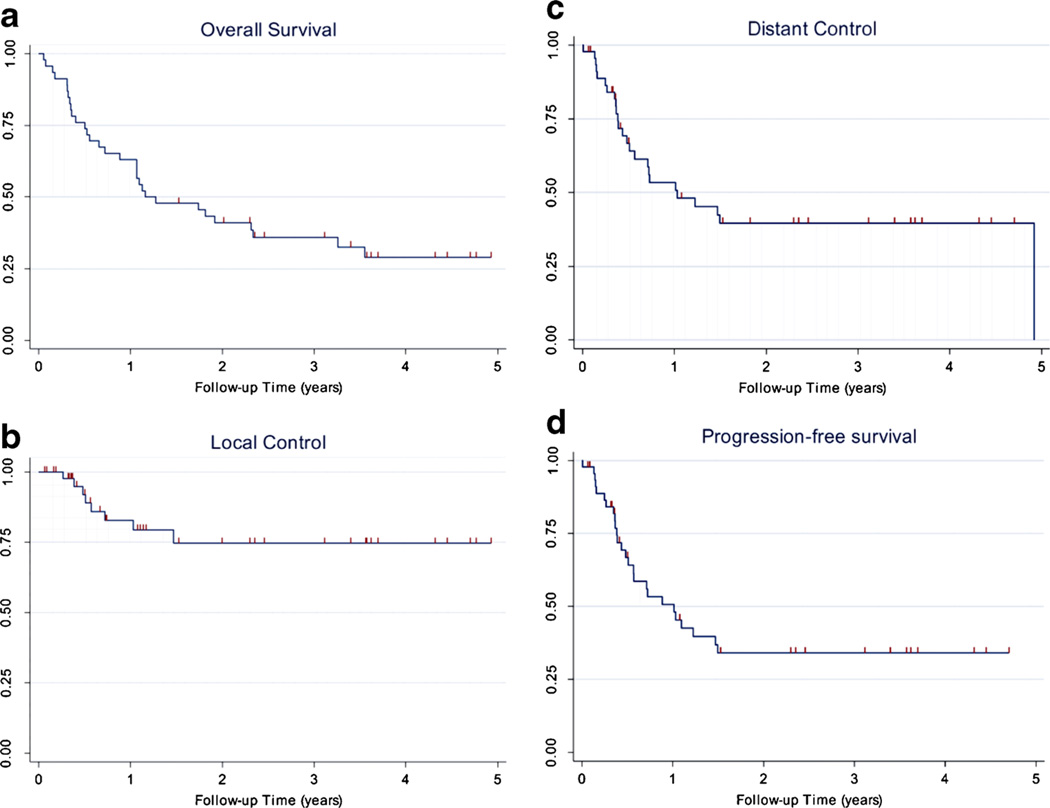

The primary end point was for this analysis is OS defined as the proportion of patients who are alive following initiation of treatment. PFS measured as time from the initiation of non-surgical treatment until last follow-up or disease progression using intent to treat principles. Failures were scored as local, regional or distant. Tumor response was assessed using Response Evaluation and Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), which was modified to incorporate PET/CT information. Local in-field recurrence was defined as progression or recurrence within the high-dose region (>80 % isodose volume). Local recurrence was calculated by patient rather than by lesion. Distant failure was defined as any recurrence outside of the high-dose radiation field. Actuarial survival and disease control rates were evaluated by the Kaplan–Meier method. For analysis of OS and PFS, deaths were considered events (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves. a Overall survival. b Local control. c Distant control. d Progression-free survival

Statistical analyses and Kaplan–Meier survival curves were calculated using Stata 8.0 (Stata, College Station, TX, USA). Cause of death was ascertained and attributed to local progression, distant progression, comorbid illness or treatment-related toxicity. The effect of patient, disease and treatment characteristics on OS was evaluated using log-rank test and Cox proportional hazards regression. Covariates evaluated in the Cox model were variables that were statistically significant on univariable analysis.

Results

Patient characteristics

Patient and tumor characteristics are summarized in Table 1. A total of 46 patients with 85 discrete metastases were treated. The median follow up for surviving patients was 3.6 years (range, 2.0–5.0 years). The most common tumor types treated were head and neck, liver, lung, kidney, and prostate cancers. The most common sites of metastases treated were bone, lung, distant lymph nodes and liver. The vast majority of patients were treated with the recommended phase II regimen of 37.5 mg sunitinib once daily on days 1–28 and SBRT 50 Gy on days 8–12 and 15–19 (Table 1). Maintenance sunitinib was used in 39 % of patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Variable | Number (%) | 4-year overall survival |

|---|---|---|

| Median age | 64 (range 47–83) | p=0.40 |

| <60 | 12 (26 %) | 43 % |

| 60–69 | 26 (37 %) | 35 % |

| ≥70 | 17 (37 %) | 15 % |

| Sex | p=0.19 | |

| Male | 32 (70 %) | 33 % |

| Female | 14 (30 %) | 19 % |

| ECOG performance status | p=0.003 | |

| 0 | 11 (24 %) | 51 % |

| 1 | 22 (48 %) | 35 % |

| 2 | 13 (28 %) | 8 % |

| Previous systemic chemotherapy | p=0.32 | |

| No | 22 (48 %) | 39 % |

| Yes | 24 (52 %) | 19 % |

| Prior RT | p=0.008 | |

| No | 25 (54 %) | 47 % |

| Yes | 21 (46 %) | 11 % |

| Number of metastases | p=0.03 | |

| 1 | 26 (57 %) | 35 % |

| 2 | 8 (17 %) | 38 % |

| ≥3 | 12 (26 %) | 17 % |

| Largest tumor size | p=0.75 | |

| ≤3 cm | 26 (57 %) | 29 % |

| >3 cm | 20 (43 %) | 28 % |

| Number of involved organs | p=0.002 | |

| 1 | 35 (76 %) | 36 % |

| ≥2 | 11 (24 %) | 9 % |

| Treatment site | 85 total tumors | p=0.008 |

| Bone | 34 (40 %) | 53 % |

| Lung | 24 (28 %) | n/a |

| Lymph node | 12 (14 %) | n/a |

| Liver | 11 (13 %) | 17 % |

| Visceral (adrenal, thyroid, inferior vena cava, chest wall) | 4 (5 %) | n/a |

| Tumor type | p=0.003 | |

| Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | 7 (15 %) | 0 % |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 7 (15 %) | n/a |

| Non-small cell lung carcinoma | 7 (15 %) | n/a |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 6 (13 %) | 83 % |

| Prostate adenocarcinoma | 5 (11 %) | 53 % |

| Colorectal adenocarcinoma | 3 (7 %) | n/a |

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | 3 (7 %) | 33 % |

| Melanoma | 2 (4 %) | 50 % |

| Other (sarcoma, breast, skin squamous cell, parotid, thyroid, small cell lung) | 6 (13 %) | 0 % |

Patterns of failure and survival

Among the 46 patients on this study, at the time of the last follow up, 12 (26 %) patients were alive without evidence of disease, three (7 %) were alive with distant metastases, 22 (48 %) were dead from distant metastases, one (2 %) was dead from local progression, six (13 %) were dead from comorbid illness, and two (4 %) were dead from treatment-related toxicities. The 4-year estimates for local control and distant control were 75 % (95 % confidence interval [CI], 55–87 %) and 40 % (95 % CI, 24–55 %), respectively. The 4-year estimates for PFS and OS were 34 % (95 % CI, 20–49 %) and 29 % (95 % CI, 16–44 %), respectively. The median PFS was 12.2 months and the median OS was 14.1 months. Details of patients with significant durable responses (≥24 months or pathologically confirmed) are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Patients with durable responses to sunitinib and radiotherapy

| Primary site | Histology | Treated sites | Follow-up (months) | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreas | Adenocarcinoma | Liver (2) | 57 | Alive NED |

| Skin | Melanoma | T9 | 54 | Alive NED |

| Prostate | Adenocarcinoma | Pubic bone | 52 | Alive NED |

| Lung | Adenocarcinoma | Iliac bone | 41 | Alive NED |

| Remains on erlotonib | ||||

| Lung | Adenocarcinoma | Rib | 45 | Alive NED |

| Kidney | Renal cell | Thyroid | 44 | Alive NED |

| Remains on sunitinib | ||||

| Prostate | Adenocarcinoma | Pubic bone | 43 | Alive NED |

| Lung | Adenocarcinoma | Lung | 38 | Alive NED |

| Remains on erlotinib | ||||

| Liver | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Lymph node | 30 | Alive NED |

| Remains on sorafenib | ||||

| Colorectal | Adenocarcinoma | Lung and hilum | 29 | Alive NED |

| Kidney | Renal cell | Iliac bone | 28 | Alive NED |

| Remains on sunitinib | ||||

| Lung | Small cell | Abdominal lymph nodes (2) | 6 | Died of comorbid illness |

| NED on autopsy |

NED No Evidence of Disease

Predictors of overall survival

The strongest predictors of improved OS on univariate analysis were lower number of metastases (p=0.03), better baseline performance status (p=0.003), no prior radiation therapy (p=0.008), only one involved organ (p=0.002) and kidney or prostate primary tumor (p=0.003). The 4-year OS was 68 % for patients with primary kidney or prostate tumors vs. 17= % for other tumor types. Among tumors with single organ involvement, patients with bone metastases had significantly improved 4-year survival compared to other sites (53 % vs. 21 %, p=0.008). Treatment factors, including radiation dose delivered (p=0.93), sunitinib dose (p=0.67) and maintenance sunitinib (p=0.20) did not predict for survival. On multivariate analysis (see Table 4), the only significant predictor of improved survival was prostate or kidney primary tumor (hazard ratio [HR]=0.25, p=0.04). There was a trend towards improved survival in patients who were not previously treated with radiotherapy (HR 0.48, p=0.07).

Table 4.

Multivariable analysis

| Variable | Hazard ratio | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Primary site (Prostate or kidney vs. other) | 0.25 | 0.04 |

| Prior radiation (No vs. yes) | 2.07 | 0.07 |

| Performance status (0 vs. 1 vs. 2) | 1.43 | 0.25 |

| Number of tumors (1 or 2 vs. ≥3) | 1.77 | 0.25 |

| Number of involved organs (1 vs. ≥2) | 1.56 | 0.36 |

| Site treated (bone only vs. other) | 1.54 | 0.41 |

Toxicity

There was no grade ≥3 acute or late toxicity directly attributable to radiation as given per protocol. There was one case of fatal hemoptysis occurring in a patient who received lumbar spine radiation on protocol who required head and neck reirradiation prior to enrolling on this study. All remaining grade ≥3 events, including one case of grade 5 gastrointestinal hemorrhage, were most likely related to sunitinib (Table 4). There were also two cases of asymptomatic grade 4 thrombocytopenia and one case of grade 4 anemia during protocol therapy. The most common grade ≥3 acute toxicities were neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, bleeding and liver function test abnormalities. Taken together, 33 % of patients experienced one or more grade ≥3 toxicities.

The six deaths attributed to comorbid illness all occurred in patients who discontinued sunitinib for at least 30 days prior to death. These deaths included two patients with cardiopulmonary arrest, two elderly patients who died peacefully at home without autopsy, one patient with subarachnoid hemorrhage outside of the radiation field and one patient with autopsy proven bronchobiliary fistula outside of the radiation field in a patient who underwent six prior lung and liver surgeries (Table 3).

Discussion

In a single institution phase I/II clinical trial of 46 patients with five or fewer metastases treated with concurrent sunitinib and SBRT, we demonstrated a 4-year PFS was 34 %, with 12 patients who are currently alive and free of disease progression at 18 to 57+ month follow-up. Various historically poor prognosis tumor types were represented among long-term survivors including renal cell carcinoma, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, melanoma, hormone-refractory prostate cancer, colorectal adenocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma and non-small cell lung cancer. Although this represents a limited cohort of heterogenous patients with oligometastases, these data provide proof of principle that durable complete remissions are possible in an appropriately selected subset of patients with oligometastases treated with sunitinib and radiotherapy.

Several recently published clinical trials reported encouraging rates of PFS and OS in patients with oligometastases treated with radiation alone. Milano and colleagues at the University of Rochester reported on 121 patients with oligometastases most commonly treated with 50 Gy in ten fractions. The 4-year local control, distant control, PFS and OS was 60 %, 25 %, 20 % and 28 %, respectively [12]. However, the 4-year OS and distant control for non-breast cancer patients was 16 % and 17 %, respectively [23]. Salama and colleagues at the University of Chicago recently reported final results of 61 patients treated on a dose escalation trial of SBRT in patients with one to five metastases. At a median follow-up of 21 months, the 2-year local control, PFS and OS was 53 %, 22 % and 57 %, respectively [11].

Since radiotherapy for oligometastases was a new concept when these pioneering studies were conducted, patient numbers were small, populations treated were hetereogenous and various radiation dose schedules were prospectively evaluated. The University of Rochester study had a higher percentage of breast primary cancer (32 %) and liver metastases (45 %) while the University of Chicago study had a greater representation of lung cancer (26 %) and patients who received prior chemotherapy (80 %) [11, 23]. In contrast, the current study was relatively well represented with hepatobiliary cancer (22 %), head and neck cancer (17 %) and osseous metastases (40 %). While prior work suggested that patients with breast cancer and lower tumor burdens as measured by aggregate size and number of metastases was associated with better outcomes, our hypothesis generating analysis identified kidney and prostate primary tumor as another favorable risk cohort [11, 23]. When attempting to analyze results of oligometastasis patients treated with radiation±sunitinib, a potential clinical benefit resulting from sunitinib cannot be ruled out. Outcomes of selected patients treated with radiotherapy±sunitinib appear to achieve higher rates of long-term progression-free and OS compared to patients with oligometastases treated with systemic therapy alone by preventing local progression [24, 25]. A randomized trial is necessary to definitively prove that integrating SBRT improves PFS and OS.

Compared to published studies investigating radiation alone for oligometastases, adding sunitinib to radiation appears to increase the rate of acute grade ≥3 toxicity [6–10]. Consistent with published experience with sunitinib alone, most toxicities were manageable [26]. However, treatment with angiogenesis inhibitors can be associated with serious or even fatal adverse events, including grade 5 hemorrhage (Table 5) [27]. Based on our experience, irradiation of significant volumes of bone marrow and liver can enhance hematological toxicities associated with sunitinib. For future clinical trials investigating radiotherapy with concurrent with sunitinib, a 25 % dose reduction (from 50 to 37.5 mg) is recommended [21].

Table 5.

Adverse events

| Adverse event | All grades | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anemia | 33 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Neutropenia | 30 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| LFT abnormalities | 26 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 25 | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| Mucositis/stomatitis | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Skin changes | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypertension | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bleeding | 6 | 1 | 0 | 2a |

| Metabolic abnormalities | 6 | 2 (PO4) | 0 | 0 |

| Increased creatinine | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Hand foot syndrome | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypothyroidism | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

One case occurred after sunitinib treatment and was likely related to reirradiation performed prior to protocol therapy

Although preclinical research investigating radiation in combination with angiogenesis inhibitors was highly promising, a significant clinical benefit has not yet been shown in humans [16]. This study demonstrates that combining sunitinib, a multitargeted tyrosine kinase angiogenesis inhibitor, with radiotherapy is feasible in various primary tumors and at various sites throughout the body. The observation that a select cohort of patients remains alive and free of progression raises the possibility that even a brief course of sunitinib during radiotherapy may offer some protective effect on micrometastases in a subset of patients. Accumulating clinical data demonstrates that sunitinb selectively targets immunosuppressive MDSC and Treg cells [18]. The abscopal effect of local radiotherapy on unirradiated distant metastases was recently demonstrated in patients receiving ipilimumab [28]. Bone marrow derived cells, including MDSC, have been implicated in tumor vasculogenesis and resistance to angiogenesis inhibitors and radiotherapy and additional work exploring the hypothesis that selective targeting of MDSC and Treg enhances the efficacy of radiotherapy is ongoing [29]. These clinical and translational data provides a strong mechanistic rationale for further investigation of concurrent sunitinib and radiotherapy for advanced malignancies.

The major strength of this study is an adequately powered cohort of patients with oligometastases treated with a novel regimen with long-term follow-up. Weaknesses include a diverse population of various primary sites, histological tumor types and metastatic sites. As a result of combining patients from phase I and II trials in a single analysis to yield reasonable statistic power, the patients were prescribed various doses of sunitinib (25 to 50 mg) and radiotherapy (40 to 50 Gy). However, sunitinib dose, radiation dose and use of maintenance sunitinib did not impact survival in univariate or multivariate analysis.

Another weakness is the radiation dose fractionation utilized in this study is a lower biologically effective dose particularly for lung and liver metastases. When the study was designed in 2005, data demonstrating the safety and efficacy of 50 Gy in ten fractions for treatment of various body sites was already published while the clinical experience for more intensive regimens was actively under investigation [7, 30] While contemporary SBRT is typically performed in ≤5 fractions primary, when combining radiotherapy with concurrent systemic therapy, a ten-fraction schedule offers some practical benefits [31]. Rather than relying on biological equivalent dose calculations, high value serial organs such as spinal cord and small bowel can be safely limited to 30 to 35 Gy in ten fractions, which are doses that have been proven safe over several decades of experience [32]. A ten fraction schedule also allows time for any biological interaction between radiotherapy and a novel agent to occur. While high rates of local control have been reported for doses of 60 Gy in three fractions for small lung and liver metastases and 18 to 24 Gy in one fraction for spine metastases, it is not yet known whether this translates into improved survival compared to more conservative regimens of 24–50 Gy in three to ten fractions [7–9, 11, 33].

Conclusions

These data add to the growing body of literature demonstrating that SBRT can achieve long-term survival in select patients with oligometastases. Although concurrent sunitinib and SBRT should not be performed outside of clinical trials secondary to increased acute toxicity, further investigation of this active regimen is warranted.

Acknowledgments

None

Conflict of interest This study was partly supported by Pfizer investigator initiated award #2005-1082 and the Ellen Katz Foundation Award to J.K. Sunitinib was provided by Pfizer.

Role of funding source This manuscript was reviewed by Pfizer prior to submission. However, the study sponsor played no involvement in study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Contributor Information

Johnny Kao, Email: johnny.kao@chsli.org, Department of Radiation Oncology, Good Samaritan Hospital Medical Center, 1000 Montauk Highway, West Islip, NY 11795, USA.

Chien-Ting Chen, Department of Medicine, New York University Medical Center, New York, NY, USA.

Charles C. L. Tong, Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY, USA

Stuart H. Packer, Department of Medical Oncology, Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY, USA

Myron Schwartz, Department of Surgery, Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY, USA.

Shu-hsia Chen, Department of Oncological Sciences, Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY, USA.

Max W. Sung, Department of Medical Oncology, Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY, USA

References

- 1.Hellman S, Weichselbaum RR. Oligometastases. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(1):8–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews DW, et al. Whole brain radiation therapy with or without stereotactic radiosurgery boost for patients with one to three brain metastases: phase III results of the RTOG 9508 randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9422):1665–1672. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patchell RA, et al. A randomized trial of surgery in the treatment of single metastases to the brain. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(8):494–500. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199002223220802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weichselbaum RR, Hellman S. Oligometastases revisited. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8(6):378–382. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Timmerman RD, et al. Local surgical, ablative, and radiation treatment of metastases. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(3):145–170. doi: 10.3322/caac.20013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee MT, et al. Phase I study of individualized stereotactic body radiotherapy of liver metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(10):1585–1591. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milano MT, et al. A prospective pilot study of curative-intent stereotactic body radiation therapy in patients with 5 or fewer oligometastatic lesions. Cancer. 2008;112(3):650–658. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rusthoven KE, et al. Multi-institutional phase I/II trial of stereotactic body radiation therapy for lung metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(10):1579–1584. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rusthoven KE, et al. Multi-institutional phase I/II trial of stereotactic body radiation therapy for liver metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(10):1572–1578. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salama JK, et al. An initial report of a radiation dose-escalation trial in patients with one to five sites of metastatic disease. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(16):5255–5259. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salama JK, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for multisite extracranial oligometastases: final report of a dose escalation trial in patients with 1 to 5 sites of metastatic disease. Cancer. 2012;118(11):2962–2970. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milano MT, et al. Oligometastases treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy: long-term follow-up of prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seiwert TY, Salama JK, Vokes EE. The concurrent chemoradiation paradigm—general principles. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4(2):86–100. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chow LQ, Eckhardt SG. Sunitinib: from rational design to clinical efficacy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(7):884–896. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.3602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karaman MW, et al. A quantitative analysis of kinase inhibitor selectivity. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(1):127–132. doi: 10.1038/nbt1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mauceri HJ, et al. Combined effects of angiostatin and ionizing radiation in antitumour therapy. Nature. 1998;394(6690):287–291. doi: 10.1038/28412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schueneman AJ, et al. SU11248 maintenance therapy prevents tumor regrowth after fractionated irradiation of murine tumor models. Cancer Res. 2003;63(14):4009–4016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozao-Choy J, et al. The novel role of tyrosine kinase inhibitor in the reversal of immune suppression and modulation of tumor microenvironment for immune-based cancer therapies. Cancer Res. 2009;69(6):2514–2522. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ko JS, et al. Sunitinib mediates reversal of myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation in renal cell carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(6):2148–2157. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong CC, et al. Phase II trial of concurrent sunitinib and image-guided radiotherapy for oligometastases. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e36979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kao J, et al. Phase 1 study of concurrent sunitinib and image-guided radiotherapy followed by maintenance sunitinib for patients with oligometastases: acute toxicity and preliminary response. Cancer. 2009;115(15):3571–3580. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wahl RL, et al. From RECIST to PERCIST: Evolving Considerations for PET response criteria in solid tumors. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(Suppl 1):122S–150S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milano MT, et al. Oligometastases treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy: long-term follow-up of prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83(3):878–886. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehta N, et al. Analysis of further disease progression in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: implications for locoregional treatment. Int J Oncol. 2004;25(6):1677–1683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rusthoven KE, et al. Is there a role for consolidative stereotactic body radiation therapy following first-line systemic therapy for metastatic lung cancer? A patterns-of-failure analysis. Acta Oncol. 2009;48(4):578–583. doi: 10.1080/02841860802662722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Motzer RJ, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):115–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ranpura V, Hapani S, Wu S. Treatment-related mortality with bevacizumab in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305(5):487–494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Postow MA, et al. Immunologic correlates of the abscopal effect in a patient with melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(10):925–931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kao J, et al. Targeting immune suppressing myeloid-derived suppressor cells in oncology. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;77(1):12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uematsu M, et al. Computed tomography-guided frameless stereotactic radiotherapy for stage I non-small cell lung cancer: a 5-year experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;51(3):666–670. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01703-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Timmerman RD, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy in multiple organ sites. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(8):947–952. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.7469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milano MT, Constine LS, Okunieff P. Normal tissue toxicity after small field hypofractionated stereotactic body radiation. Radiat Oncol. 2008;3:36. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-3-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerszten PC, et al. CyberKnife frameless stereotactic radio-surgery for spinal lesions: clinical experience in 125 cases. Neurosurgery. 2004;55(1):89–98. discussion 98–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]