Abstract

Basic neuroscience research provides strong evidence for the role of oxytocin in olfactory processes and social affiliation in rodents. Given prior indication of olfactory impairments that are linked to greater severity of asociality in schizophrenia, we examined the association between plasma oxytocin levels and measures of olfaction and social outcome in a sample of outpatients with schizophrenia (n = 39) and demographically matched healthy controls (n = 21). Participants completed the 40-item University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT), and rated each odor for how positive and how negative it made them feel. Results indicated that individuals with schizophrenia had higher plasma oxytocin levels and lower overall accuracy for UPSIT items than controls. Individuals with schizophrenia also reported experiencing more negative emotionality than controls in response to the olfactory stimuli. Lower plasma oxytocin levels were associated with poorer accuracy for pleasant and unpleasant odors and greater severity of asociality in individuals with schizophrenia. These findings suggest that endogenous oxytocin levels may be an important predictor of olfactory identification deficits and negative symptoms in schizophrenia.

Keywords: Oxytocin, Olfaction, Emotion, Hedonic, Negative Symptoms, Psychosis

1.0. Introduction

Basic neuroscience research provides strong evidence for the role of oxytocin in olfactory processes and social affiliation. For example, the olfactory bulb is rich in oxytocin receptors and ablation of the olfactory bulb impairs social recognition and affiliative bonding between mothers and their offspring (Dantzer et al., 1990; Dickinson, 1988). Conversely, bulbar administration of oxytocin enhances social discrimination and social memory (Dluzen et al., 1998). Thus, studies in rodents and other mammals provide evidence for a link between social behavior and oxytocin functioning in the olfactory bulb (Wacker and Ludwig, 2012).

Individuals with schizophrenia display a range of olfactory processing abnormalities, including deficits in odor identification, discrimination, detection threshold sensitivity, hedonic judgments, and memory (for review see Moberg et al., 2014). These impairments are evident as early as the prodromal and first episode periods and may worsen throughout the course of illness (Brewer et al., 2003; Kamath et al., 2014; Woodberry et al., 2010). Importantly, poor olfactory identification and lower hedonic judgments for pleasant odors have been associated with greater severity of negative symptoms, especially reduced social drive (Hudry et al., 2002; Malaspina and Coleman, 2003; Malaspina et al., 2002; Moberg et al., 2003; Strauss et al., 2010). It has yet to be determined whether endogenous oxytocin levels mediate the association between social functioning and olfactory processing in schizophrenia, as might be expected based on the basic neuroscience literature.

To date, relatively few studies have examined endogenous oxytocin levels in schizophrenia. There is inconsistency among findings, with some studies reporting that people with schizophrenia who are polydipsic have lower endogenous oxytocin levels than healthy controls (Goldman et al., 2008; Goldman et al., 2011), some reporting higher levels in people with schizophrenia (Beckmann et al., 1985), and others reporting no group differences (Rubin et al., 2014; Rubin et al., 2013; Rubin et al., 2011; Rubin et al., 2010). Furthermore, lower endogenous oxytocin has been associated with greater severity of positive and negative symptoms, poor social functioning, impaired facial affect perception, abnormal judgment of gaze direction, and impaired theory of mind (Goldman et al., 2008; Keri et al., 2009; Rubin et al., 2011; Rubin et al., 2010; Walss-Bass et al., 2013). Acute challenge and multi-dose clinical trials have produced inconsistent results (Horta de Macedo et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2013); however, there is some evidence that intranasal administration of oxytocin improves psychiatric symptoms and social cognition (Averbeck et al., 2012; Davis et al., 2014; Davis et al., 2013; Feifel et al., 2010; Fischer-Shofty et al., 2013a; Fischer-Shofty et al., 2013b; Gibson et al., 2014; Pedersen et al., 2011; Woolley et al., 2014), as well as olfactory identification (Lee et al., 2013).

The current study aimed to extend this literature by directly examining the association between plasma oxytocin, social functioning, symptoms, olfactory identification, and olfactory hedonic judgments. We hypothesized that people with schizophrenia would have lower plasma oxytocin levels than healthy controls, and that lower endogenous oxytocin would be associated with poor olfactory identification accuracy, lower hedonic ratings for pleasant stimuli, greater severity of negative symptoms, and poor community-based social outcome.

2.0. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants included 39 individuals meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision criteria for schizophrenia and 21 healthy controls.

Participants with schizophrenia (SZ) were recruited from the outpatient research program at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center and evaluated during periods of clinical stability. Consensus diagnosis was established via a best-estimate approach based on psychiatric history and multiple interviews and subsequently confirmed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID: First et al., 2001). All participants in the SZ group met DSM-IV lifetime diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, were assessed after a minimum period of 4 weeks of stable treatment, and prescribed an antipsychotic medication at the time of testing.

Control subjects (CN) were recruited through random-digit dialing and word of mouth among enrolled participants. All CN underwent a screening interview, including the SCID-I and SCID-II (Pfol et al., 1997) and did not meet criteria for any current Axis I or II disorder or lifetime criteria for a psychotic disorder. CN also had no family history of psychosis. No participants met criteria for substance dependence in the last 6 months and all denied lifetime history of neurological disorders associated with cognitive impairment (e.g., Traumatic Brain Injury, Epilepsy). Lack of substance use in the week prior to the study was confirmed by urine toxicology. Female participants completed a pregnancy screen, as this can affect oxytocin levels; no participants were pregnant.

Individuals with SZ and CN did not significantly differ in age, parental education, sex, or ethnicity. People with schizophrenia had lower personal education than controls.

2.2. Procedures

Participants completed a standard clinical interview that was performed by a clinical psychologist (GPS) trained to MPRC reliability standards (reliability >0.80). After this interview, patients were rated on the Brief Negative Symptom Scale (BNSS: Kirkpatrick et al., 2011; Strauss et al., 2012,ab), Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS: Overall & Gorham, 1962), and Level of Function Scale (LOF: Hawk et al., 1975).

The University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT: Doty et al., 1984) is a standardized olfactory perception measure that requires identification of 40 common microencapsulated odors by selecting one of four multiple-choice answers consisting of various odor names. The UPSIT was administered birhinally by a trained technician. After identifying the odor of each item, participants reported how positive and how negative the odor made them feel using separate unipolar rating scales. Each rating scale ranged from 1 (not at all) to 9 (extremely). Separate rating scales were used for positive and negative emotions, rather than a bipolar valence scale (i.e., ranging from extremely unpleasant to extremely pleasant), because emotional stimuli can induce co-activations of positive and negative emotion.

Several UPSIT score calculations were derived. In addition to calculating the global UPSIT total accuracy score, we also calculated valence-specific accuracy scores based upon procedures established by other published studies using the UPSIT in schizophrenia (Strauss et al., 2010; Kamath et al., 2010). Using these procedures, the 40 odorants were divided into pleasant, neutral, and unpleasant valence categories using published pleasantness ratings from the UPSIT manual (Doty et al., 1984):16 items were categorized as pleasant, 15 items were categorized as neutral, and 9 items were categorized as unpleasant. Separate accuracy scores for pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral items were calculated. Additionally, ratings of self-reported positivity and negativity were calculated separately for the pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral items.

Plasma oxytocin levels were determined by radioimmunoassay using a magnetic bead kit from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Samples were assayed in duplicate; the average of these samples was taken as the final oxytocin value. Assay sensitivity was 5 pg/ml, with minimal cross reactivity with vasopressin. The coefficient of variation averaged 5–8% across the assay.

3.0. Results

3.1. Endogenous Oxytocin Levels

One-way ANOVA indicated that people with schizophrenia had significantly higher plasma oxytocin levels than controls, F (1, 59) = 6.93, p <0.01 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Schizophrenia (n = 39) |

Controls (n = 21) |

Test-statistic, p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 43.9 (11.7) | 42.6 (9.3) | F = 0.2, p= 0.65 |

| Participant Education | 13.1 (2.1) | 15.1 (1.9) | F = 14.3, p <0.001 |

| Parental Education | 13.6 (2.5) | 14.3 (2.4) | F = 0.99, p = 0.33 |

| % Male | 72% | 67% | χ2 = 0.68, p = 0.33 |

| Ethnicity | χ2 = 1.2, p = 0.77 | ||

| Caucasian | 89.7% | 95.2% | |

| African-American | 5.1% | 4.8% | |

| Native-American | 2.6% | 0.0% | |

| Bi-racial | 2.6% | 0.0% | |

| Plasma Oxytocin (pg/ml) | 24.5 (7.5) | 19.7 (5.9) | F = 6.9, p < 0.02 |

| CPZ Equivalent Dosage (mg) | 610.0 (394) | -- | -- |

| Symptoms | |||

| BNSS Total | 24.8 (17.5) | -- | -- |

| BPRS Total | 38.1 (9.6) | -- | -- |

| BPRS Positive | 2.4 (1.1) | -- | -- |

| BPRS Negative | 2.2 (1.1) | -- | -- |

| BPRS Disorganized | 1.5 (0.5) | -- | -- |

| Functional Outcome | |||

| LOF Total | 19.1 (7.7) | -- | -- |

| LOF Social | 4.7 (2.6) | -- | -- |

| LOF Work | 2.1 (2.8) | -- | -- |

Note. CPZ = Chlorpromazine Equivalent Dosage; BNSS = Brief negative Symptom Scale; BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; LOF = Level of Function Scale

3.2. Olfactory Identification

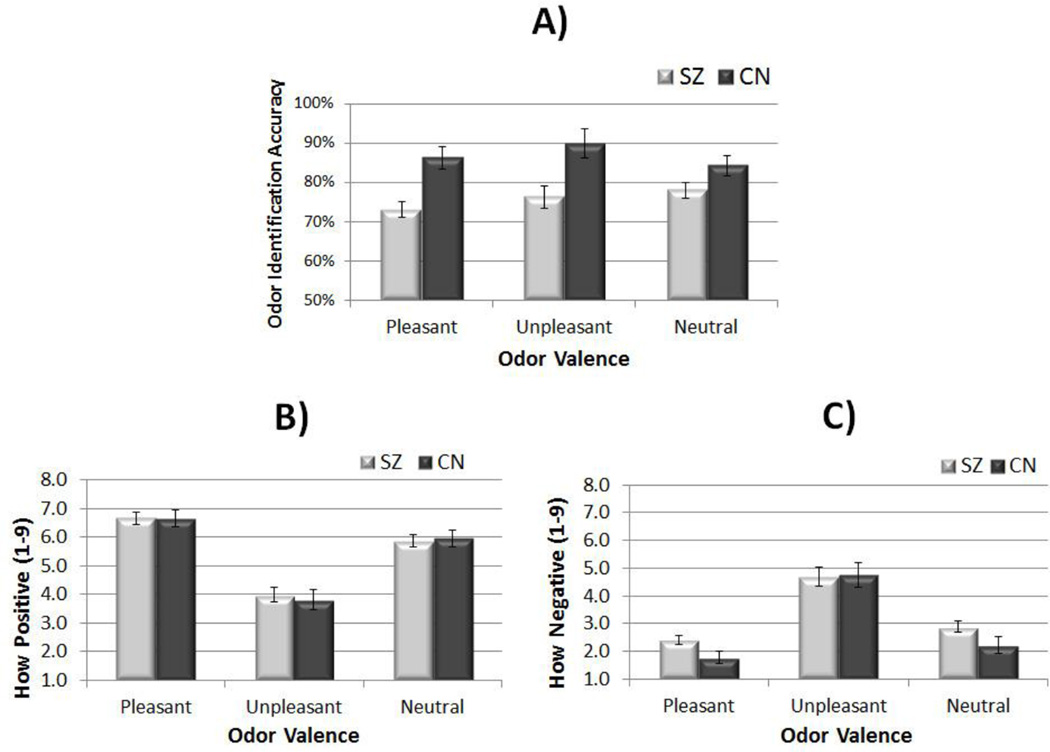

MANOVA investigating accuracy across valence conditions indicated a significant overall effect, F (1, 59) = 6.16, p < 0.001, as well as significant individual effects for Pleasant: F (1, 59) = 15.22, p < 0.001 and Unpleasant odors: F (1, 59) = 8.46, p < 0.01. There was a trend toward participants with schizophrenia being less accurate than controls for neutral odors: F (1, 59) = 3.75, p = 0.058 (see Figure 1, panel A). Thus, people with schizophrenia had poorer olfactory identification than controls.

Figure 1.

Olfactory Identification and Emotional Experience Ratings for Pleasant, Unpleasant, and Neutral Odors

Note. SZ = schizophrenia; CN = control; A = Odor identification accuracy per valence category; B = Ratings of how positive participants reported feeling in response to pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral stimuli; C = Ratings of how negative participants reported feeling in response to pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral stimuli

3.3. Olfactory Emotional Experience Ratings

Using self-reports of how positive participants felt in relation to pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral odors, MANOVA revealed a nonsignificant Group effect, F (3, 56) = 0.30, p = 0.82 (see Figure 1, panel C), and nonsignificant effects for all 3 conditions.

MANOVA revealed a significant overall effect for how negative individuals with schizophrenia and controls reported feeling to unpleasant, neutral, and pleasant stimuli, F (3, 56) = 3.25, p < 0.03, such that participants with schizophrenia reported more negative emotion than controls. There was a significant individual effect for pleasant odors, F (1, 58) = 4.84, p < 0.04, a trend for neutral odors, F (1, 58) = 3,44, p = 0.069,and a nonsignificant difference for unpleasant odors, F (1, 58) = 0.02, p = 0.89.

3.4. Correlations

In participants with SZ, lower plasma oxytocin levels were significantly associated with poorer identification accuracy for all UPSIT items and unpleasant items; there was a trend toward a significant association with pleasant items, but not neutral items. Self-reports of how positive participants with SZ felt in relation to neutral stimuli were significantly associated with lower oxytocin levels; however, associations between oxytocin and all other emotional experience ratings were nonsignificant. In CN, plasma oxytocin levels were not significantly associated with olfactory identification or emotional experience ratings (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations between Oxytocin, Olfaction, and Clinical Presentation

| SZ | CN | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | r | p | |

| UPSIT Accuracy | ||||

| Pleasant Items | 0.29 | 0.08 | −0.14 | 0.56 |

| Unpleasant Items | 0.33 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.85 |

| Neutral Items | 0.09 | 0.59 | 0.25 | 0.3 |

| Total | 0.38 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.9 |

| How Negative Ratings | ||||

| Unpleasant Items | 0.11 | 0.53 | 0.17 | 0.47 |

| Pleasant Items | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.14 | 0.55 |

| Neutral items | 0.17 | 0.32 | 0.10 | 0.68 |

| How Positive Ratings | ||||

| Pleasant Items | −0.09 | 0.61 | 0.23 | 0.33 |

| Unpleasant Items | −0.25 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.77 |

| Neutral Items | −0.35 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.34 |

| Symptoms and Functional Outcome | ||||

| BNSS Total | −0.38 | 0.01 | -- | -- |

| BNSS Asociality | −0.37 | 0.02 | -- | -- |

| BPRS Positive | −0.08 | 0.64 | -- | -- |

| BPRS Negative | −0.35 | 0.03 | -- | -- |

| BPRS Disorganization | 0.04 | 0.83 | -- | -- |

| BPRS Total | −0.26 | 0.11 | -- | -- |

| LOF Total | 0.37 | 0.02 | -- | -- |

| LOF Social | 0.33 | 0.04 | -- | -- |

| LOF Work | 0.23 | 0.15 | -- | -- |

In participants with SZ, significant associations were observed between plasma oxytocin levels and the BNSS total score, BNSS asociality, BPRS negative symptom factor, LOF total, and LOF social outcome, but not LOF work outcome, BPRS positive, BPRS disorganized, or BPRS total scores (see Table 2). Olfactory identification accuracy and olfactory hedonic ratings were not significantly associated with symptom or functional outcome measures. Chlorpromazine equivalent dosage (Woods, 2003) was not significantly associated with plasma oxytocin levels or UPSIT task performance. None of the significant correlations observed in SZ survived bonferroni correction.

Analyses were also conducted to evaluate item-level associations between accuracy and subjective ratings of positive and negative emotion within each group. In both CN and SZ, higher ratings of positive emotion were associated with better accuracy (SZ: r = 0.17, p < 0.001; CN: r = 0.17; p <0.001) and higher ratings of negative emotion were associated with poorer accuracy (SZ: r = −0.14, p < 0.001; CN: r = −0.08, p = 0.015).

4.0. Discussion

Consistent with hypotheses, findings provided novel evidence that lower endogenous oxytocin levels predict poorer olfactory identification accuracy. These findings suggest that individual differences in endogenous oxytocin levels predict olfactory identification in people with schizophrenia, and are consistent with prior work indicating that intranasal administration of oxytocin enhances identification of pleasant odors (Lee et al., 2013).

Findings also replicate prior evidence for an association between lower endogenous oxytocin levels and greater severity of negative symptoms, including asociality (Keri et al., 2009; Rubin et al., 2010). However, we did not find evidence for diminished plasma oxytocin levels in participants with schizophrenia, as has been reported in those with polydipsia (Goldman et al., 2008, 2011); rather, we fond elevated concentrations, consistent with Beckman et al (1985). It is possible that differences among studies reflect the relative sampling of participants with polydipsia, given that Goldman et al. (2008) found that that oxytocin levels were lower and negative symptoms were higher in polydipsic groups with and without hyponatremia. Measures of polydipsia were not obtained in the current study.

Contrary to hypotheses, negative symptoms and social functional outcome were not significantly correlated with olfactory identification or olfactory emotional experience ratings. These null findings contradict several prior studies (Malaspina and Coleman, 2003; Malaspina et al., 2002; Strauss et al., 2010). Inconsistency between current and prior results cannot be attributed to atypical olfactory identification findings or reduced variance in negative symptom severity in our sample, as our schizophrenia group was enriched for negative symptoms and had total UPSIT scores that were comparable to past studies.

Furthermore, we did not replicate prior reports for an association between lower hedonic ratings for pleasant odors and negative symptoms (Strauss et al., 2010), nor were there significant correlations between plasma oxytocin and hedonic ratings. Rather, people with schizophrenia reported experiencing more negative emotionality than controls in response to neutral and pleasant odors, but there were no group differences in self-reported positive emotion to pleasant stimuli. This pattern of self-report is consistent with prior studies using other types of emotional stimuli to study emotional experience in schizophrenia such as photographs, film clips, and sounds (Cohen and Minor, 2010; Cohen et al., 2011; Kring and Moran, 2008; Strauss and Gold, 2012). Specifically, studies on emotional experience in schizophrenia typically report that people with schizophrenia and controls do not differ in self-reported positive emotion (Cohen & Minor, 2010) or arousal (Llerena et al., 2012) to pleasant stimuli; however, individuals with schizophrenia report elevated negative emotionality to unpleasant, neutral, and pleasant stimuli (Cohen & Minor, 2010). These findings have led some to suggest that abnormalities in negative, rather than positive emotional experience are core to affective dysfunction in schizophrenia (Cohen et al., 2011; Strauss and Gold, 2012; Strauss et al., 2013). In light of inconsistency among olfactory hedonic findings, additional studies are needed to determine whether this modern conceptualization of emotional experience in schizophrenia is consistent across stimulus types, or whether olfactory stimuli are unique in suggesting a true anhedonia (i.e., diminished capacity for positive emotion to pleasant stimuli).

Our results also replicated another emotional experience abnormality that is commonly seen in schizophrenia using other stimulus types, which has been termed “affective ambivalence” (Tremeau et al., 2009). Specifically, people with schizophrenia have been found to report feeling more positive emotion to unpleasant stimuli than controls, as well as more negative emotion to pleasant stimuli (Tremeau et al., 2009). This finding has been interpreted as reflecting a greater co-activation of positive and negative emotions to evocative stimuli in schizophrenia. To our knowledge, the current study is the first to demonstrate that these patterns of emotional self-report also extend to olfactory stimuli.

Findings should be interpreted in light of certain limitations. First, sample size was modest, limiting power to detect small effects. Second, only one measure of olfactory processing was administered, the UPSIT and the order of olfactory judgments may have introduced an expectancy effect. Specifically, having identification precede hedonic judgment ratings may have influenced how participants perceived an odor's valence because they may have been rating the label they provided instead of the stimulus itself. Future studies should consider changing the order of hedonic ratings and identification, as well as examining the association between oxytocin and other olfactory measures, including odor detection threshold, discrimination, and memory. Third, assay method may play an important role in determining whether endogenous oxytocin levels are abnormal in people with schizophrenia. A radioimmunoassay was used in the current study; however, enzyme immunoassay without extraction may offer better sensitivity and specificity for oxytocin (Carter et al., 2007). It is possible that different assay methods may produce different results. Fourth, the role of antipsychotic medications is unclear. All participants in the schizophrenia group were prescribed antipsychotics at the time of testing. D2 antagonists may increase oxytocin levels, thereby resulting in group differences driven by medication use in the schizophrenia group. Finally, we could not evaluate oxytocin receptor function. It is possible that higher oxytocin levels in the schizophrenia group reflect a compensatory response to a lower sensitivity of the oxytocin receptor to circulating levels of the hormone. Additionally, it is not clear whether peripheral oxytocin levels reflect oxytocin levels or function in the brain, and caution should be made when making conclusions about potential neural mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants who completed the study, as well as staff at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center who contributed to data collection. We are especially thankful to Dana Brady for processing oxytocin levels and members of Dr. Strauss’ team who conducted subject recruitment and testing: Lauren Catalano, Adam Culbreth, Bern Lee, Jamie Adams, Travis White, Tehreem Galani, and Carol Vidal.

Role of Funding Source.

Research supported in part by US National Institutes of Mental Health Grant P50-MH082999 (WT Carpenter) and a Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Illness Research Education Clinical Centers VISN 5 pilot grant (GP Strauss)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

Gregory Strauss, William Keller, Robert Buchanan, James Koenig, and James Gold designed the study. Statistical analyses and writing of the first draft of the manuscript were performed by Gregory Strauss. James Koenig and his lab conducted oxytocin radioimmunoassays. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the current study.

References

- Averbeck BB, Bobin T, Evans S, Shergill SS. Emotion recognition and oxytocin in patients with schizophrenia. Psychological medicine. 2012;42(2):259–266. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann H, Lang RE, Gattaz WF. Vasopressin--oxytocin in cerebrospinal fluid of schizophrenic patients and normal controls. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1985;10(2):187–191. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(85)90056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer WJ, Wood SJ, McGorry PD, Francey SM, Phillips LJ, Yung AR, Anderson V, Copolov DL, Singh B, Velakoulis D, Pantelis C. Impairment of olfactory identification ability in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis who later develop schizophrenia. The American journal of psychiatry. 2003;160(10):1790–1794. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AS, Minor KS. Emotional experience in patients with schizophrenia revisited: meta-analysis of laboratory studies. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2010;36(1):143–150. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AS, Najolia GM, Brown LA, Minor KS. The state-trait disjunction of anhedonia in schizophrenia: potential affective, cognitive and social-based mechanisms. Clinical psychology review. 2011;31(3):440–448. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, Tazi A, Bluthe RM. Cerebral lateralization of olfactory-mediated affective processes in rats. Behavioural brain research. 1990;40(1):53–60. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(90)90042-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MC, Green MF, Lee J, Horan WP, Senturk D, Clarke AD, Marder SR. Oxytocin-augmented social cognitive skills training in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(9):2070–2077. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MC, Lee J, Horan WP, Clarke AD, McGee MR, Green MF, Marder SR. Effects of single dose intranasal oxytocin on social cognition in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2013;147(2–3):393–397. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson C, Keverne EB. Importance of noradrenergic mechanisms in the olfactory bulbs for the maternal behaviour of mice. Physiol. Behav. 1988;43:313–316. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(88)90193-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dluzen DE, Muraoka S, Landgraf R. Olfactory bulb norepinephrine depletion abolishes vasopressin and oxytocin preservation of social recognition responses in rats. Neuroscience letters. 1998;254(3):161–164. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00691-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feifel D, Macdonald K, Nguyen A, Cobb P, Warlan H, Galangue B, Minassian A, Becker O, Cooper J, Perry W, Lefebvre M, Gonzales J, Hadley A. Adjunctive intranasal oxytocin reduces symptoms in schizophrenia patients. Biological psychiatry. 2010;68(7):678–680. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Shofty M, Brune M, Ebert A, Shefet D, Levkovitz Y, Shamay-Tsoory SG. Improving social perception in schizophrenia: the role of oxytocin. Schizophrenia research. 2013a;146(1–3):357–362. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Shofty M, Shamay-Tsoory SG, Levkovitz Y. Characterization of the effects of oxytocin on fear recognition in patients with schizophrenia and in healthy controls. Frontiers in neuroscience. 2013b;7:127. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson CM, Penn DL, Smedley KL, Leserman J, Elliott T, Pedersen CA. A pilot six-week randomized controlled trial of oxytocin on social cognition and social skills in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2014;156(2–3):261–265. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman M, Marlow-O'Connor M, Torres I, Carter CS. Diminished plasma oxytocin in schizophrenic patients with neuroendocrine dysfunction and emotional deficits. Schizophrenia research. 2008;98(1–3):247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman MB, Gomes AM, Carter CS, Lee R. Divergent effects of two different doses of intranasal oxytocin on facial affect discrimination in schizophrenic patients with and without polydipsia. Psychopharmacology. 2011;216(1):101–110. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2193-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horta de Macedo LR, Zuardi AW, Machado-de-Sousa JP, Chagas MH, Hallak JE. Oxytocin does not improve performance of patients with schizophrenia and healthy volunteers in a facial emotion matching task. Psychiatry research. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.07.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudry J, Saoud M, D'Amato T, Dalery J, Royet JP. Ratings of different olfactory judgements in schizophrenia. Chemical senses. 2002;27(5):407–416. doi: 10.1093/chemse/27.5.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath V, Turetsky BI, Calkins ME, Kohler CG, Conroy CG, Borgmann-Winter K, Gatto DE, Gur RE, Moberg PJ. Olfactory processing in schizophrenia, non-ill first-degree family members, and young people at-risk for psychosis. The world journal of biological psychiatry : the official journal of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry. 2014;15(3):209–218. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.615862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keri S, Kiss I, Kelemen O. Sharing secrets: oxytocin and trust in schizophrenia. Social neuroscience. 2009;4(4):287–293. doi: 10.1080/17470910802319710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kring AM, Moran EK. Emotional response deficits in schizophrenia: insights from affective science. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2008;34(5):819–834. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MR, Wehring HJ, McMahon RP, Linthicum J, Cascella N, Liu F, Bellack A, Buchanan RW, Strauss GP, Contoreggi C, Kelly DL. Effects of adjunctive intranasal oxytocin on olfactory identification and clinical symptoms in schizophrenia: results from a randomized double blind placebo controlled pilot study. Schizophrenia research. 2013;145(1–3):110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llerena K, Strauss GP, Cohen AS. Looking at the other side of the coin: a meta-analysis of self-reported emotional arousal in people with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2012;142(1–3):65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaspina D, Coleman E. Olfaction and social drive in schizophrenia. Archives of general psychiatry. 2003;60(6):578–584. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.6.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaspina D, Coleman E, Goetz RR, Harkavy-Friedman J, Corcoran C, Amador X, Yale S, Gorman JM. Odor identification, eye tracking and deficit syndrome schizophrenia. Biological psychiatry. 2002;51(10):809–815. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01319-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moberg PJ, Arnold SE, Doty RL, Kohler C, Kanes S, Seigel S, Gur RE, Turetsky BI. Impairment of odor hedonics in men with schizophrenia. The American journal of psychiatry. 2003;160(10):1784–1789. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen CA, Gibson CM, Rau SW, Salimi K, Smedley KL, Casey RL, Leserman J, Jarskog LF, Penn DL. Intranasal oxytocin reduces psychotic symptoms and improves Theory of Mind and social perception in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2011;132(1):50–53. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin LH, Carter CS, Bishop JR, Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Drogos LL, Hill SK, Ruocco AC, Keedy SK, Reilly JL, Keshavan MS, Pearlson GD, Tamminga CA, Gershon ES, Sweeney JA. Reduced Levels of Vasopressin and Reduced Behavioral Modulation of Oxytocin in Psychotic Disorders. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2014 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin LH, Carter CS, Bishop JR, Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Harris MS, Hill SK, Reilly JL, Sweeney JA. Peripheral vasopressin but not oxytocin relates to severity of acute psychosis in women with acutely-ill untreated first-episode psychosis. Schizophrenia research. 2013;146(1–3):138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin LH, Carter CS, Drogos L, Jamadar R, Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Sweeney JA, Maki PM. Sex-specific associations between peripheral oxytocin and emotion perception in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2011;130(1–3):266–270. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin LH, Carter CS, Drogos L, Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Sweeney JA, Maki PM. Peripheral oxytocin is associated with reduced symptom severity in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2010;124(1–3):13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss GP, Allen DN, Ross SA, Duke LA, Schwartz J. Olfactory hedonic judgment in patients with deficit syndrome schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2010;36(4):860–868. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss GP, Gold JM. A new perspective on anhedonia in schizophrenia. The American journal of psychiatry. 2012;169(4):364–373. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11030447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss GP, Kappenman ES, Culbreth AJ, Catalano LT, Lee BG, Gold JM. Emotion regulation abnormalities in schizophrenia: cognitive change strategies fail to decrease the neural response to unpleasant stimuli. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2013;39(4):872–883. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremeau F, Antonius D, Cacioppo JT, Ziwich R, Jalbrzikowski M, Saccente E, Silipo G, Butler P, Javitt D. In support of Bleuler: objective evidence for increased affective ambivalence in schizophrenia based upon evocative testing. Schizophrenia research. 2009;107(2–3):223–231. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacker DW, Ludwig M. Vasopressin, oxytocin, and social odor recognition. Hormones and behavior. 2012;61(3):259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walss-Bass C, Fernandes JM, Roberts DL, Service H, Velligan D. Differential correlations between plasma oxytocin and social cognitive capacity and bias in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2013;147(2–3):387–392. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodberry KA, Seidman LJ, Giuliano AJ, Verdi MB, Cook WL, McFarlane WR. Neuropsychological profiles in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis: relationship to psychosis and intelligence. Schizophrenia research. 2010;123(2–3):188–198. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SW. Chlorpromazine equivalent doses for the newer atypical antipsychotics. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2003;64(6):663–667. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley JD, Chuang B, Lam O, Lai W, O'Donovan A, Rankin KP, Mathalon DH, Vinogradov S. Oxytocin administration enhances controlled social cognition in patients with schizophrenia. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;47:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]