Abstract

After decades of unfulfilled promise, immunotherapies for cancer have finally reached a tipping point, with several FDA approved products now on the market and many more showing promise in both adult and pediatric clinical trials. Tumor cell expression of MHC Class I has emerged as a potential determinant of the therapeutic success of many immunotherapy approaches. Here we review current knowledge regarding MHC Class I expression in pediatric cancers including a discussion of prognostic significance, the opposing influence of MHC on T-cell versus NK-mediated therapies, and strategies to reverse or circumvent MHC down-regulation.

Keywords: MHC Class I, immunotherapy, childhood cancers

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 15,780 children (birth to 19 years) are diagnosed with cancer each year in the United States, where it is the most common cause of childhood and adolescent death by disease [1]. Chemotherapy and radiation have been iteratively enhanced through the use of clinical trials over the past several decades, resulting in improved cure rates for many cancer types. Progress using these traditional therapies, however, has plateaued and short and long term toxicities remain significant problems [2]. In contrast, immune-based therapies are gaining traction with reports of antitumor efficacy in adults. As these therapies begin testing in children, it is important for pediatric oncologists to understand key components of immunotherapy and be cognizant of gaps in knowledge in order to refine and implement these treatments for childhood cancers.

MHC 101

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is a multi-gene family that encodes a series of cell surface proteins that function to bind and present antigens to the adaptive immune system. While MHC is evolutionarily conserved among all species with adaptive immune systems, it is also one of the most highly polymorphic regions of the human genome, underscoring both its necessity in the formation of adaptive immune responses and the evolutionary pressure on this family of proteins to maintain immunologic fitness.

In humans, MHC, known as human leukocyte antigen (HLA), is encoded on chromosome 6, from 6p22.1 to 6p21.3, and is composed of 240 genes [3]. MHC class I is expressed by all nucleated cells and, together with the beta-2-microglobulin chain, functions to display short peptide antigens derived from either intracellular pathogens or endogenous self-antigens. In contrast, MHC class II is expressed by a specialized group of immune cells that capture and present antigens derived from extracellular pathogens. The focus of this article is on MHC class I, due to its known roles in tumor immune surveillance and escape.

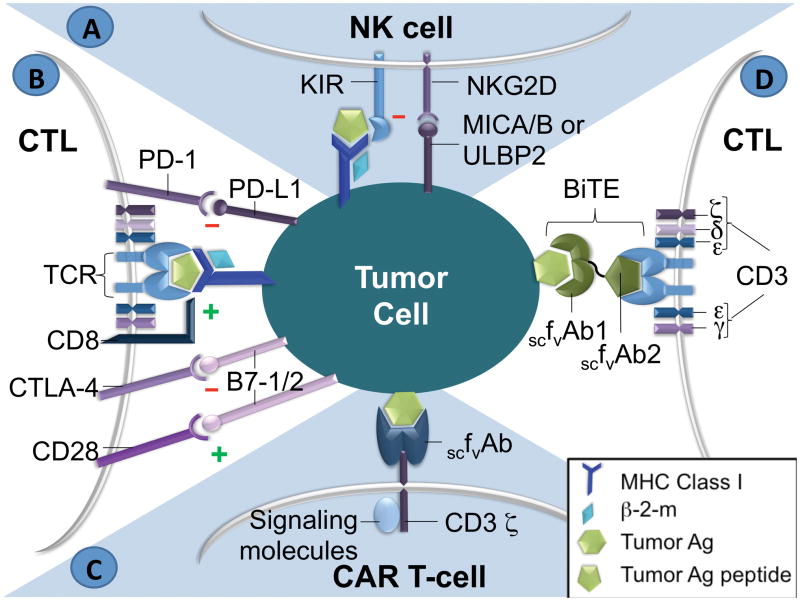

The immunologic executioners ultimately resulting from MHC peptide presentation are cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs, CD8+) for the adaptive immune response and natural killer (NK) cells for the innate immune response. CTLs require tumor antigen presentation on the target cell by MHC Class I molecules to delineate self from non-self, whereas those created by insertion of genes encoding T cell chimeric antigen receptors recognizing native cell surface antigens do not (Fig. 1). In contrast to T cells, class I MHC molecules typically serve as inhibitory signals for NK cells, classically thought to provide protection from NK-mediated autoimmunity.

Figure 1.

A) NK cell interaction with antigen (Ag) on tumor cell. Both inhibitory and stimulatory ligands are shown. B) Antigen presentation to a T-cell in the context of MHC Class I. C) Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR). D) Bi-specific T-cell Engager (BiTE). CTL: cytotoxic T-lymphocyte, TCR: T-cell receptor, β-2-m: beta-2-microglobulin, Ag: antigen, KIR: Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor, scFvAb: single chain variable fragment of antibody

MHC DOWNREGULATION: A COMMON MECHANISM OF TUMOR IMMUNE ESCAPE

Despite progress in the development and refinement of immune-based therapies, there are limitations to T- and NK cell-mediated responses. Almost all tumors evade an immune response through multiple mechanisms, including the down-regulation of MHC class I and tumor-specific antigens, establishment of an immunosuppressive microenvironment, and subsequent hyporesponsiveness of anti-tumor effector cells. One of the most common means by which tumors evade the host immune response is by down-regulation of MHC Class I molecule expression, thereby rendering any endogenous or therapeutic anti-tumor T cell responses ineffective.

Several mechanisms of MHC Class I down-regulation have been identified, yielding seven different phenotypes [4]. Phenotype I is the total loss of HLA expression, while Phenotype II is defined by haplotype loss. Phenotype III comprises classical HLA (A, B, or C) down-regulation, and Phenotype IV includes HLA allelic loss. Phenotype V involves compound phenotypes, with a combination of two different alterations. Phenotype VI involves unresponsiveness to interferons, while Phenotype VII is the down-regulation of classical HLA molecules with the appearance of HLA-E molecules.

Most often, the loss of MHC expression on tumor cells is mediated by epigenetic events and transcriptional down-regulation of the MHC locus and/or the antigen processing machinery. Lack of a processed peptide leads to decreased MHC expression since empty MHC molecules are not stable on the cell surface. These mechanisms for MHC down-regulation are reversible; for example, DNA hypermethylation and histone acetylation can be reversed by administration of demethylation chemotherapy and HDAC inhibitors [4,5]. Another reversible mechanism of the down-regulation of classical HLA Class I (A/B/C) is through the up-regulation of the non-classical Class I HLAs (E/F/G) [4]. Some mechansims have been shown to be irreversible, such as gene mutations involving the HLA Class I heavy chain or the beta-2-microglobulin subunit.

MHC CLASS I EXPRESSION IN ADULT TUMORS

MHC Class I expression is reportedly repressed in 40–90% of human tumors [6], in some cases correlating with worse prognosis [7–9] (Table 1). In colorectal cancer, high MHC class I expression on tumors identified patients with improved survival, with a significant correlation noted between the presence of intratumoral T-cells and MHC class I expression [9,10]. A pathologic immunoscore which quantifies the in situ immune infiltrate has been developed to determine prognosis in colorectal cancer, where it has been found to be more prognostic than TNM staging, and other tumors [11]. In breast and esophageal cancers, MHC Class I and HER2 expression were inversely correlated [12,13]; knock down of HER2 with siRNA in the latter models caused up-regulation of MHC class I expression, leading to increased CTL recognition by tumor antigen-specific CTLs [13]. In endometrial cancer, the absence of non-classical HLA-G expression was independently associated with MHC class I down-regulation, a known down-regulation mechanism phenotype [7]. However, for tonsillar squamous cell carcinomas, no significant correlation was found between the non-classical HLA-E or HLA-G and HPV status or clinical outcome [14].

Table I.

MHC Class I expression in adult cancers.

| Adult Tumor Type | MHC Class 1 Expression | Prognostic Indications | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Carcinoma | Down-regulated | Strong expression correlated with improved survival; Predicts immunotherapy response in vitro |

Simpson et al. 2010, Bubenik 2004, Lechner etal.2013 |

| Breast Adenocarcinoma | Down-regulated | Inversely correlated with HER2 expression; Predicts immunotherapy response in vitro |

Inoue et al. 2012, Bubenik 2004, Lechner et al. 2013 |

| Endometrial Carcinoma | Down-regulated | Down-regulation predictor of worse survival | Bijen et al. 2010 |

| Cervical Carcinoma | Down-regulated | Bubenik 2004 | |

| Tonsillar Squamous Cell Carcinoma | HPV-positive: low expression correlated with favorable outcome; HPV-negative: normal expression correlated with favorable outcome |

Näsman et al. 2013 | |

| Head and Neck Carcinomas | Down-regulated | Bubenik 2004 | |

| Prostate Carcinoma | Down-regulated | Bubenik 2004 | |

| Melanoma | Down-regulated | Predicts immunotherapy response in vitro | Lechner et al. 2013, Bubenik 2004 |

| Renal Cortical Adenocarcinoma | Low | Predicts immunotherapy response in vitro | Lechner et al. 2013 |

| Lung Carcinoma | Down-regulated | Down-regulation unfavorable prognostic factor in tumors with cancer testis antigen expression; Predicts immunotherapy response in vitro |

Hanagiri et al. 2013, Bubenik 2004, Lechner et al. 2013 |

MHC CLASS I EXPRESSION IN PEDIATRIC TUMORS

Few studies have examined Class I expression in pediatric cancers, and only in a limited number of patients (Table 2).

Table II.

MHC Class I expression in pediatric cancers.

| Pediatric Tumor Type | “Classical” MHC Class I (HLA-A, -B, -C) | “Nonclassicai” MHC Class I (HLA-E. -F, -G) | Prognostic Indications | Comments | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medulloblastoma | Expression associated with unfavorable prognostic marker expression | Smith et al. 2009 | |||

| Neuroblastoma | Low | High HLA-G | Lower stage associated with higher expression | Reversible epigenetic mechanism | Forloni et al. 2010, Wölfl et al. 2005, Lorenzi et al. 2012, Pistoia et al. 2013, Pajtler et al. 2013, Morandi et al. 2013 |

| Ewing Sarcoma/PNET | Low | Variable | Decreased expression associated with disease progression | Reversible epigenetic mechanism | Peters et al. 2013, Berghuis et al. 2009, Thiel et al. 2012, Borowski et al. 1999 |

| Osteosarcoma | HLA-D up-regulated | Mechtersheimer et al. 1990 | |||

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | Some up-regulated; Poorly differentiated negative |

Compared to normal muscle cells | Mechtersheimer et al. 1990 | ||

| ALL | No change in expression | HLA-G up-regulated after treatment | Reid et al. 2003, Motawi et al. 2012 |

Neuroblastoma

The most extensively studied pediatric tumor for MHC expression is neuroblastoma, which has particularly low MHC Class I expression, especially in high-risk patients [15]. Dysregulated NF-κB causes both low MHC Class I and decreased expression of the antigen processing machinery required for the appropriate conformational folding of the MHC molecule. In some cases, these proteins can be re-expressed by exposure to IFN-γ [16,17]. Some neuroblastoma cells express the B7H3 co-stimulatory molecule, a known potent inhibitor of T-cell activation. Additionally, neuroblastomas with low classical (HLA-A, -B, and -C) MHC Class I expression have higher non-classical HLA expression (HLA-E, -F, and -G), whose levels in plasma correlated with worse survival [18]. The precise implications of these features on the outcome of currently open neuroblastoma vaccine trials (e.g., NCT00911560) have yet to be determined [19].

Ewing sarcoma

The majority (79%) of Ewing sarcomas exhibit partial or complete absence of MHC Class I expression, with lung metastases consistently being negative [20]. These cancers are mostly HLA-A and HLA-B negative with significant HLA-C expression. In many cases Class I expression can be up-regulated by IFNγ and radiation [21], [22].

Medulloblastoma

MHC Class I expression in medulloblastomas is associated with poor prognostic factors, a pattern opposite most other cancers [23]. Interestingly, despite MHC expression, NK-cell based therapies may be a viable strategy for medulloblastomas [24]. In a study performed by Fernandez et al., 54 medulloblastoma tumor samples were analyzed for expression of MHC Class I-related chains A (MICA) and UL16 binding protein (ULPB-2), known ligands for the NK group 2 member D activating receptor (NKG2D). The authors reported high expression of MICA on primary medulloblastoma cells and demonstrated that blocking HLA Class I on these cells overpowers the inhibition seen by HLA Class I overexpression on tumor cells [24].

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Although poorly differentiated rhabdomyosarcomas are negative for classical HLA Class I, the few cases that have been examined showed robust Class I expression in other subtypes [25].

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia

The majority of ALL cases have Class I MHC expression [26,27]. In addition, non-classical HLA-G was up-regulated after chemotherapy treatment [26]. No significant differences in MHC Class I expression were seen between diagnostic and relapsed samples in pre-B ALL [26].

Very little literature exists classifying MHC Class I expression in other pediatric malignancies. The paucity of data raises questions as to which immunotherapies may be applicable for the treatment of these diseases. Further characterization of MHC Class I expression in pediatric malignancies will be required to understand the potential use of immune-based therapies, and may determine whether an approach for a specific cancer type should be MHC Class I-dependent or -independent. MHC Class I status may serve as a biomarker for patient inclusion in immunotherapeutic trials, though it may be more prudent to consider it a dynamic marker, as its expression may be responsive to interferons and highly regulated by the tumor microenvironment. Although a particular tumor type may prove to be MHC Class I expression negative, modulation of its expression may be a viable strategy to enhance the efficacy of T-cell based immunotherapies.

MHC-DEPENDENT IMMUNOTHERAPIES: VACCINES AND TILs

CTLs contribute to the anti-tumoral adaptive immune response and offer such advantages as a persistent effect (memory) and ability to travel to distant sites of metastasis. Several T-cell-based immunotherapies are currently under study, such as autologous transplantation of tumor-specific T-cells and dendritic cell vaccines [28].

Collection of autologous T-cells or, ideally, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) followed by their ex vivo stimulation, expansion, and re-infusion, has proven to be effective in an increasing number of cancers [29,30]. In situations which use donor T-cells with mismatched HLA types from the recipient, however, MHC Class I restriction results in rapid clearance of the therapeutic T-cells by the patient’s own immune system as a response to foreign cells. Vaccination by various strategies is also used to induce anti-tumor T-cells in situ [28]. Several ex vivo and in vivo versions of vaccines have been studied in which antigen presenting cells are exposed either to peptides known to be expressed on the patient’s tumor or whole autologous tumor lysates. These vaccines are often combined with immunologic adjuvants to further boost the immune response. Vaccine types encompass whole tumor cell vaccines, known antigen vaccines, DNA-based vaccines, and vector-based vaccines. Of these, only one dendritic cell vaccine is FDA-approved, indicated for hormone-resistant advanced stage prostate cancer (Sipuleucel-T a.k.a. Provenge) [31]. This vaccine uses dendritic cells exposed to prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP), and has been shown to extend patient’s lives by an average of 4 months. Side effects include fever, chills, fatigue, back and joint pain, nausea, and headache.

Several known MHC-restricted immune targets exist in pediatric cancers [28]. Cancer Testis Antigens (CTAs) are relatively recently discovered proteins expressed on several malignancies. Some of these are highly immunogenic, and interestingly, as an adjunct to vaccines, have been found to be epigenetically up-regulated on tumors with exposure to demethylating chemotherapy agents [32]. There also exist non-CTA MHC-restricted antigens in pediatric cancers, including differentiation antigens and oncogenes.

Another method for targeted tumor destruction as well as induction of anti-tumor T-cell immunity is oncolytic virotherapy. This strategy of producing attenuated viruses targeted to specifically infect cancer cells and induce an anti-tumor immune response is an emerging treatment with several open clinical trials [33]. Use of oncolytic viruses has been shown to have direct lytic effects on infected tumor cells without pathologic infection of normal host tissues. In some cases, viruses induce a so-called immunologic cell death, resulting in effective tumor antigen presentation and generation of an adaptive antitumor immune response [34]. The infection with virus also induces a host immune response against the virus itself, leading to the ultimate clearance of the therapeutic virus. CTLs are also the major players in viral clearance, and many viruses down regulate MHC Class I expression in infected cells as a means to evade the host T-cell immune response.

Interference of cell-facilitated elimination of cancer cells may occur due to several factors, such as the immunosuppressive microenvironment in many solid tumors (TGFβ, IL-10, regulatory T-cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells), all of which can affect both T- and NK cells. Executioner cells may also be physically excluded from tumors by abnormal tumor vascularization, and several clinical trials are currently in progress which target tumor pro-angiogenic factors to mitigate this effect (NCT01810744, NCT01047293, NCT01377025). In addition, T-cells are subject to intrinsic regulation (such as granule content) and extrinsic factors (such as the presence of suppressor cells or suppressive chemokines and cytokines) [31].

Tumor cell-immune system interactions can also be limited through escape mechanisms such as decreased tumoral expression of antigens, chemokines, and adhesion molecules. There are currently several studies looking at inhibitors of critical T-cell check-points such as PD-1 and CTLA-4. In adult cancers such as melanoma, antibodies which block these receptors have shown encouraging results [35]. It is prudent to keep in mind that these strategies which promote endogenous TIL activity by blocking the immunosuppressive microenvironment are still restricted to MHC Class I expression.

STRATEGIES TO ENHANCE MHC CLASS I: CYTOKINES, HDAC INHIBITORS, AND CHEMOTHERAPEUTICS

Dependent upon the specific mechanism and therefore the reversibility of its down-regulation, MHC Class I can be up-regulated under various circumstances. If alterations of antigen presentation machinery gene expression (such as TAP and LMP) are the etiology of MHC Class I down-regulation, reversal can be seen with the addition of such cytokines as IFN-γ and TNF-α. During the progression of a cellular immune response, IL-2 and Type I interferons, among others, are released to stimulate the recruitment and activation of more CTLs. These cytokines also induce the up-regulation of MHC Class I expression. Epigenetic defects resulting in DNA hypermethylation or aberrant non-classical and low classical HLA gene expression are also reversible mechanisms for MHC Class I down-regulation. These can be modified by DNA demethylating agents such as azacitidine, decitabine and histone hyperacetylation through the use of histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, such as Vorinostat [36]. The clinical trial NCT00561912 involved the use of low dose Decitabine plus IFN-α2b in advanced renal cell carcinoma patients. However, only 2 patients registered in the trial between October 2007 and July 2008, and the study was terminated in November 2009 due to low accrual. There are several currently ongoing clinical trials using epigenetic modulators, including among others NCT01498445, NCT00918489, NCT01064921.

STRATEGIES TO CIRCUMVENT LOW MHC CLASS I: BiTES AND CAR Ts

Some immunotherapy approaches, such as bi-specific T-cell engager antibodies (BiTE) and T-cells engineered to express chimeric antigen receptors (CAR T), target native cell surface antigens and are therefore independent of MHC expression. Because CAR Ts usually express single chain engineered T-cell receptors, most are capable of bypassing the MHC Class I restriction of other T-cell therapies (Fig. 2). Phase I clinical studies of CAR Ts have shown efficacy in leukemia, with a fraction of the T-cells in these patients displaying a memory phenotype as well.

BiTE antibodies are another example of engaging a cellular immunotherapy that bypasses the need for tumor antigen presentation in MHC class I. BiTes are fusion proteins of two single-chain variable fragments (scFv) of different antibodies linked by a single peptide chain. One scFv binds T-cells via the CD3 receptor, while the other scFv binds tumor cells via a tumor-associated antigen. These are used as a means to direct host CTLs against cancer cells independent of MHC Class I expression or the presence of co-stimulatory molecules (Fig. 3). For example, Blinatumomab (MT103) is an anti-CD19 (B cell surface molecule) BiTE used in the treatment of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and acute lymphoblastic lymphoma (NCT00274742, NCT01466179, NCT02000427, NCT02013167, NCT01471782).

These MHC-independent approaches require a known antigenic target, a luxury not always apparent for many pediatric cancers. Also, these studies tend to target liquid cancers, with known cell surface targets. There are additional challenges associated with the treatment of solid tumors, including the physical capability for penetration of T-cells into the tumor and the presence of an immunosuppressive microenvironment.

STRATEGIES THAT CAPITALIZE ON LOW MHC EXPRESSION: NK CELL THERAPIES

NK cells are a subset of lymphocytes that contribute to innate immunity, capable of lysing tumor cells without prior sensitization using the same killing mechanisms as CTLs. NK recognition of target cells is multifaceted and comprised of interactions between both activating and inhibitory receptors and their corresponding ligands [37,38]. The presence of the MHC Class I molecule on target cells serves as one such inhibitory ligand for MHC Class I-specific receptors, the Killer cell Immunoglobulin-like Receptor (KIR), on NK cells. Engagement of KIR receptors blocks NK activation and, paradoxically, preserves their ability to respond to successive encounters by triggering inactivating signals [39]. Therefore, if a KIR is able to sufficiently bind to MHC Class I, this engagement may override the signal for killing and allows the target cell to live. In contrast, if the NK cell is unable to sufficiently bind to MHC Class I on the target cell, killing of the target cell may proceed. Consequently, those tumors which express low MHC Class I and are thought to be capable of evading a T-cell-mediated attack may actually be susceptible to an NK cell-mediated immune response instead. The regulation NK cell reactivity is quite complex, however, as the decision to kill represents the integration of inhibitory and activating signals. In some cases, NK cells will kill despite the presence of inhibitory KIR ligands if the activating signals are sufficiently strong.

NK cell regulation, identification of self and non-self, and self tolerance are brought about partially through inhibitory KIR interactions with cognate HLA class I ligands. For example, the inhibitory KIR receptors (2DL1, 2DL2, 2DL3, and 3DL1) signal following binding to specific HLA I alleles. A single NK cell may express one or more KIRs and NK cells possess KIR inventories which consist of one or more KIRs with specificity to self HLA I ligands [40]. However, because functional competence of NK cells occurs by continuous signaling from an inhibitory KIR associating with self HLA I molecules and because KIR and HLA genes are on different chromosomes and independently segregate, some persons may have KIR genes without the corresponding HLA ligand [40], but do not experience NK alloreactivity or associated clinically relevant autoimmunity symptoms, as may be expected. This phenomenon can be explained by the “missing ligand model,” whereby NK cells express KIRs with specificity for non-self HLA Class I ligands. As they are developing, these NK cells are not licensed by self HLA Class I ligands and are therefore thought to be hyporesponsive to physiologic stimulation [40].

NK cell recognition of missing self HLA class I molecules on target cancer cells has been postulated to improve hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) outcomes. Graft versus leukemia (GVL) effects of KIR-ligand incompatability have been observed in T-cell-depleted haplotype-mismatched grafts in AML patients [40]. An anti-leukemic effect has also been observed due to allo-reactive (KIR/HLA mismatched) donor NK cells in haplo-identical stem cell transplant in high-risk ALL patients [41]. However, results from studies involving mismatched unrelated HSCT and umbilical cord blood grafts are inconsistent, and may be attributed to other variables.

Expansion and adoptive transfer of human haplo-identical NK cells has been shown to be safe in AML patients [42]. Haplo-identical allogeneic NK cell infusions have also been utilized in Hodgkin lymphoma patients as well as in various adult solid tumors, such as melanoma and renal cell carcinoma [40]. An immunosuppressive conditioning regimen with lympho-depletion was required to promote NK cell expansion in all studies. Currently, unstimulated or IL-2-activated donor NK cell infusions are used for haplo-identical HSCT patients for relapse prevention and no abrupt or serious adverse effects have been reported [40].

Clinical protocols to procure, enrich, and expand purified NK cells are achievable through the use of umbilical cord blood or apheresis and continue to be optimized [40]. Another approach to NK cell-based immunotherapies is the development of CAR NK cells. Similar to their cousins, the CAR T cells, these are engineered using a monoclonal antibody to recognize a specific antigenic target expressed on the tumor cell surface linked to intracellular signaling which ultimately stimulates the effector cell. As an proof-of-principle, adoptive transfer of CAR NK cells efficiently suppressed growth of human IM9 multiple myeloma cells in vivo and significantly prolonged mouse survival [43].

SUMMARY

Immune-based therapies are developing rapidly with recent successes in some adult cancers. T-cells, specifically CTLs, contribute to the anti-tumoral adaptive immune response and offer such advantages as long-term surveillance (memory) and ability to travel to distant sites of metastasis. MHC Class I antigen presentation is required for T-cells to delineate self from non-self. Several T-cell-based immunotherapies are currently under study, such as autologous transplantation of tumor-specific T-cells and dendritic cell vaccines [28]. Numerous known MHC-restricted targets exist in pediatric cancers, such as cancer-selective antigens. In contrast, some immunotherapy approaches, such as T-cells engineered to express chimeric receptors and bi-specific antibodies, are MHC-independent. NK cells, a major contributor to the innate immune response, may offer advantages in the context of low MHC Class I expression.

Despite the progressive development of immune-based therapies, challenges remain. Tumor cell-immune system interactions are diminished through escape mechanisms including loss of MHC Class I expression, which correlates with poorer prognosis in several adult cancers. Which of these mechanisms contribute to immune escape in pediatric tumors has not been systematically evaluated. MHC Class I status may serve as a biomarker for patient inclusion in immunotherapeutic trials, and modulation of its expression may be a promising strategy to enhance immunotherapy efficacy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and NIH grants P01 CA163205 and R21 CA166790.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ward E, Desantis C, Robbins A, et al. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(2):83–103. doi: 10.3322/caac.21219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith MA, Seibel NL, Altekruse SF, et al. Outcomes for children and adolescents with cancer: challenges for the twenty-first century. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15):2625–2634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Complete sequence and gene map of a human major histocompatibility complex. The MHC sequencing consortium. Nature. 1999;401(6756):921–923. doi: 10.1038/44853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia-Lora A, Algarra I, Garrido F. MHC class I antigens, immune surveillance, and tumor immune escape. J Cell Physiol. 2003;195(3):346–355. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Licciardi PV, Karagiannis TC. Regulation of immune responses by histone deacetylase inhibitors. ISRN Hematol. 2012;2012:690901. doi: 10.5402/2012/690901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bubenik J. MHC class I down-regulation: tumour escape from immune surveillance? (review) Int J Oncol. 2004;25(2):487–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bijen CB, Bantema-Joppe EJ, de Jong RA, et al. The prognostic role of classical and nonclassical MHC class I expression in endometrial cancer. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(6):1417–1427. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanagiri T, Shigematsu Y, Kuroda K, et al. Prognostic implications of human leukocyte antigen class I expression in patients who underwent surgical resection for non-small-cell lung cancer. J Surg Res. 2013;181(2):e57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simpson JA, Al-Attar A, Watson NF, et al. Intratumoral T cell infiltration, MHC class I and STAT1 as biomarkers of good prognosis in colorectal cancer. Gut. 2010;59(7):926–933. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.194472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lechner MG, Karimi SS, Barry-Holson K, et al. Immunogenicity of murine solid tumor models as a defining feature of in vivo behavior and response to immunotherapy. J Immunother. 2013;36(9):477–489. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000436722.46675.4a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galon J, Mlecnik B, Bindea G, et al. Towards the introduction of the ‘Immunoscore’ in the classification of malignant tumours. The Journal of pathology. 2014;232(2):199–209. doi: 10.1002/path.4287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue M, Mimura K, Izawa S, et al. Expression of MHC Class I on breast cancer cells correlates inversely with HER2 expression. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1(7):1104–1110. doi: 10.4161/onci.21056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maruyama T, Mimura K, Sato E, et al. Inverse correlation of HER2 with MHC class I expression on oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2010;103(4):552–559. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nasman A, Andersson E, Nordfors C, et al. MHC class I expression in HPV positive and negative tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma in correlation to clinical outcome. Int J Cancer. 2013;132(1):72–81. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolfl M, Jungbluth AA, Garrido F, et al. Expression of MHC class I, MHC class II, and cancer germline antigens in neuroblastoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54(4):400–406. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0603-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lorenzi S, Forloni M, Cifaldi L, et al. IRF1 and NF-kB restore MHC class I-restricted tumor antigen processing and presentation to cytotoxic T cells in aggressive neuroblastoma. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e46928. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forloni M, Albini S, Limongi MZ, et al. NF-kappaB, and not MYCN, regulates MHC class I and endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidases in human neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70(3):916–924. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morandi F, Cangemi G, Barco S, et al. Plasma levels of soluble HLA-E and HLA-F at diagnosis may predict overall survival of neuroblastoma patients. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:956878. doi: 10.1155/2013/956878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krishnadas DK, Shapiro T, Lucas K. Complete remission following decitabine/dendritic cell vaccine for relapsed neuroblastoma. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e336–341. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berghuis D, de Hooge AS, Santos SJ, et al. Reduced human leukocyte antigen expression in advanced-stage Ewing sarcoma: implications for immune recognition. The Journal of pathology. 2009;218(2):222–231. doi: 10.1002/path.2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borowski A, van Valen F, Ulbrecht M, et al. Monomorphic HLA class I-(non-A, non-B) expression on Ewing’s tumor cell lines, modulation by TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma. Immunobiology. 1999;200(1):1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0171-2985(99)80029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peters HL, Yan Y, Solheim JC. APLP2 regulates the expression of MHC class I molecules on irradiated Ewing’s sarcoma cells. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2(10):e26293. doi: 10.4161/onci.26293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith C, Santi M, Rajan B, et al. A novel role of HLA class I in the pathology of medulloblastoma. J Transl Med. 2009;7:59. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernandez L, Portugal R, Valentin J, et al. In vitro Natural Killer Cell Immunotherapy for Medulloblastoma. Front Oncol. 2013;3:94. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mechtersheimer G, Staudter M, Majdic O, et al. Expression of HLA-A,B,C, beta 2-microglobulin (beta 2m), HLA-DR, -DP, -DQ and of HLA-D-associated invariant chain (Ii) in soft-tissue tumors. Int J Cancer. 1990;46(5):813–823. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910460512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Motawi TM, Zakhary NI, Salman TM, et al. Serum human leukocyte antigen-G and soluble interleukin 2 receptor levels in acute lymphoblastic leukemic pediatric patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(11):5399–5403. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.11.5399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reid GS, Terrett L, Alessandri AJ, et al. Altered patterns of T cell cytokine production induced by relapsed pre-B ALL cells. Leuk Res. 2003;27(12):1135–1142. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(03)00106-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orentas RJ, Lee DW, Mackall C. Immunotherapy targets in pediatric cancer. Front Oncol. 2012;2:3. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Shelton TE, et al. Generation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte cultures for use in adoptive transfer therapy for melanoma patients. J Immunother. 2003;26(4):332–342. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200307000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kvistborg P, Shu CJ, Heemskerk B, et al. TIL therapy broadens the tumor-reactive CD8(+) T cell compartment in melanoma patients. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1(4):409–418. doi: 10.4161/onci.18851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palucka K, Banchereau J. Dendritic-cell-based therapeutic cancer vaccines. Immunity. 2013;39(1):38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krishnadas D, et al. Cancer Testis Antigen and Immunotherapy. Immunotargets and Therapy. 2013;2:11–19. doi: 10.2147/ITT.S35570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miest TS, Cattaneo R. New viruses for cancer therapy: meeting clinical needs. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12(1):23–34. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Workenhe ST, Mossman KL. Oncolytic virotherapy and immunogenic cancer cell death: sharpening the sword for improved cancer treatment strategies. Mol Ther. 2014;22(2):251–256. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ott PA, Hodi FS, Robert C. CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade: new immunotherapeutic modalities with durable clinical benefit in melanoma patients. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2013;19(19):5300–5309. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Magner WJ, Kazim AL, Stewart C, et al. Activation of MHC class I, II, and CD40 gene expression by histone deacetylase inhibitors. J Immunol. 2000;165(12):7017–7024. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Long EO. Negative signaling by inhibitory receptors: the NK cell paradigm. Immunol Rev. 2008;224:70–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00660.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palmer JM, Rajasekaran K, Thakar MS, et al. Clinical relevance of natural killer cells following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Cancer. 2013;4(1):25–35. doi: 10.7150/jca.5049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Long EO, Kim HS, Liu D, et al. Controlling natural killer cell responses: integration of signals for activation and inhibition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:227–258. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chouaib S, Pittari G, Nanbakhsh A, et al. Improving the Outcome of Leukemia by Natural Killer Cell-Based Immunotherapeutic Strategies. Front Immunol. 2014;5:95. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Locatelli F, Pende D, Maccario R, et al. Haploidentical hemopoietic stem cell transplantation for the treatment of high-risk leukemias: how NK cells make the difference. Clin Immunol. 2009;133(2):171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller JS, Cooley S, Parham P, et al. Missing KIR ligands are associated with less relapse and increased graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) following unrelated donor allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2007;109(11):5058–5061. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-065383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chu J, Deng Y, Benson DM, et al. CS1-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-engineered natural killer cells enhance in vitro and in vivo antitumor activity against human multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2014;28(4):917–927. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]