Abstract

BACKGROUND

Increasing pressures to provide high quality evidence-based cancer care have driven the rapid proliferation of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs). The quality and validity of CPGs have been questioned and adherence to guidelines is relatively low. The purpose of this study is to critically evaluate the development process and scientific content of CPGs.

METHODS

CPGs addressing management of rectal cancer were evaluated. We quantitatively assessed guideline quality with the validated Appraisal of Guidelines Research & Evaluation (AGREE II) instrument. We identified 21 independent processes of care using the Nominal Group Technique. We then compared the evidence base and scientific agreement for the management recommendations for these processes of care.

RESULTS

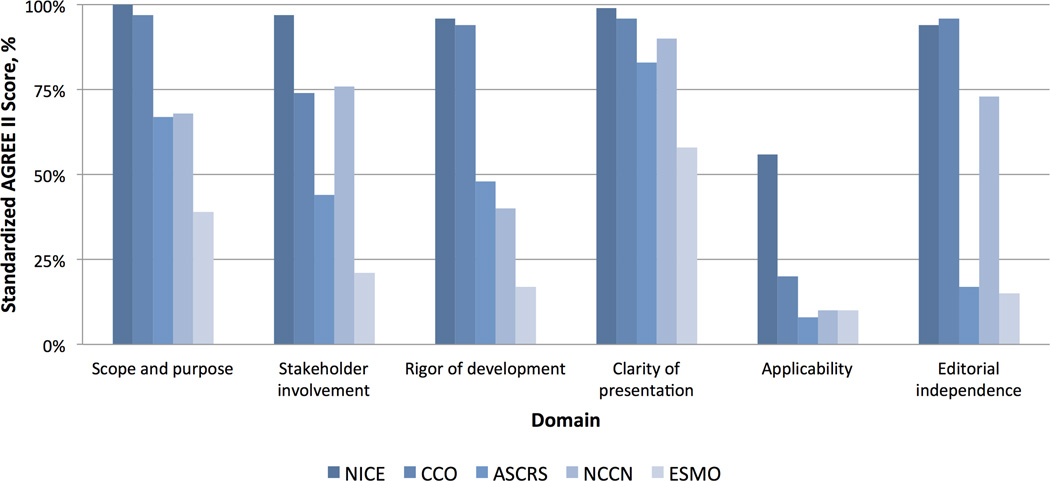

The quality and content of rectal cancer CPGs varied widely. Mean overall AGREE II scores ranged from 27–90%. Across the five CPGs, average scores were highest for the clarity of presentation domain (85%, range 58% to 99%) and lowest for the applicability domain (21%, range 8% to 56%). Randomized controlled trials represented a small proportion of citations (median 18%, range 13–35%), 78% of the recommendations were based on low or moderate quality evidence, and the CPGs only had 11 references in common with the highest rated CPG. There were conflicting recommendations for 13 of the 21 care processes assessed (62%).

CONCLUSION

There is significant variation in CPG development processes and scientific content. With conflicting recommendations between CPGs, there is no reliable resource to guide high-quality evidence-based cancer care. The quality and consistency of CPGs are in need of improvement.

Keywords: Evidence-based medicine, Practice guidelines, Rectal neoplasms, Organizations, Health services

INTRODUCTION

There are increasing pressures to provide evidence-based cancer care and to document concordance with quality standards. Recognizing these needs, there has been a rapid proliferation of clinical practice guideline (CPG) recommendations over the last decade.1 These CPGs aim to consolidate findings from an increasingly expansive clinical research literature and to develop standardized approaches to high quality care. However, concordance with guideline recommendations remains inadequate.2–4

Many have posited that clinicians’ lack of adherence to guidelines may be due to a distrust in how CPGs are developed and in the recommendations that are put forth.5 Developers of CPG often fail to adhere to widely-endorsed standards for the development of high-quality guidelines.6–9 These standards aim to improve the quality of CPGs, ensure freedom from bias, and increase likelihood of broad endorsement. Further, little attention has been given to disagreement in scientific content between CPGs. Conflicting recommendations may result from either differences in the evidence base used to synthesize recommendations or differences in interpretation of the same evidence. It is not known whether adherence to standards for high-quality CPG development might be associated with the use of higher-quality evidence.

In this context, we sought to critically evaluate CPGs based on their overall development quality, the evidence base used to synthesize recommendations, and the scientific agreement between CPGs on key processes of care. An understanding of this relationship will help cancer care providers determine the reliability of CPG recommendations and better inform their clinical decision making.

METHODS

In this study, we focus on recommendations for the management of rectal cancer. Rectal cancer requires well-coordinated, multidisciplinary care and, given highly variable patient outcomes, is a disease site in need of more standardized care and promulgation of best practices. Further, the evidence base for rectal cancer care is large and diverse, ranging from expert opinion to results from randomized controlled trials. This focus on one disease site allows for an in depth evaluation of the quality and content of specific care recommendations within the guidelines.

Five specialty societies or government-funded organizations producing rectal cancer CPGs listed in the National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC) and the Standards and Guidelines Evidence (SAGE) databases were selected from 17 societies and organizations via author consensus prior to data collection. Only authoring organizations that published on the multi-disciplinary management of rectal cancer were included. The selected organizations and societies represent the key authorities in rectal cancer care in North America and Europe and were felt to have credibility with large constituencies, namely: American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS)10; Cancer Care Ontario (CCO);11–14 European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO)15; National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)16; and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).17 The most up-to-date versions of the CPG documents and the authoring organizations were obtained from their respective webpages. Only documents published between 2008–2014 were included in the analysis to ensure a contemporary comparison between CPGs with access to a similar evidence base.

The process of development and quality of reporting for each CPG was assessed using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation (AGREE II) instrument.18 The AGREE II is widely accepted as the international gold standard for the appraisal of guidelines,19 developed by organizations in various settings. The instrument is comprised of 23 items within six quality domains: 1) scope and purpose; 2) stakeholder involvement; 3) rigor of development; 4) clarity of presentation; 5) applicability; and 6) editorial independence. Each item is rated on a seven point Likert scale. The AGREE II instrument allows for up to four appraisers to independently rate CPGs. Raters were blinded to each other’s ratings, and achieved high inter-rater reliability as evident by weighted kappa scores of 0.7 – 0.9. The Likert ratings from all four raters are used to compute a standardized score from 0–100% for each domain per AGREE standards. For CPGs with multiple documents that address different aspects of care (i.e., CCO), the raters considered the documents collectively as one.

The CPG with the highest AGREE II six-domain average was then used as the benchmark for comparing process of care recommendations across CPGs. Using the Nominal Group Technique20–22 we identified recommended processes relevant to the care of rectal cancer, across five clinical categories: 1) diagnosis and staging; 2) preoperative therapy; 3) operative management; 4) postoperative therapy; and 5) surveillance. The authors discussed each of the identified processes in a round-robin feedback session, and were given the opportunity to clarify their opinion regarding the relative importance of each care process, including the option of adding processes that were not initially identified. The authors then separately prioritized the identified processes. Overlapping processes of care were consolidated, ranked consecutively and those with broad consensus were included. A final list of 21 distinct processes of care was developed. This list was redistributed to each panel member for approval. We evaluated the evidence used to inform recommendations for each of the 21 processes of care and compared the citations, level of evidence (high vs. low or moderate quality evidence) and the strength of the recommendations as reported by the CPG authors to the highest rated CPG.

The complete reference list for each CPG was manually reviewed. Each citation was crosschecked with the reference list of the highest rated CPG to identify shared references.

All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA special edition (version 13, StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Guideline Development: Organizational and CPG Characteristics

The characteristics of the CPG authoring organization are summarized in Table 1. Three are professional specialty societies or consortiums (ASCRS, ESMO, and NCCN) and two are government-associated multidisciplinary agencies (NICE and CCO). In all authoring organizations, a panel of individuals with clinical expertise was convened for the synthesis of CPG recommendations. The CPG panel was comprised of multidisciplinary membership in all but one organization since ASCRS included only colon and rectal surgeons on their panel. Patient advocates were included on CCO, NCCN, and NICE panels, but not on ASCRS or ESMO panels. Financial support for the guideline developmental process originated from either the budget of professional organizations/societies (ASCRS, ESMO, and NCCN) or grants issued by the government or government-affiliated agencies (NICE and CCO).

Table 1.

Organizational and document characteristics for rectal cancer clinical practice guidelines (CPGs).

| Clinical Practice Guidelines Authoring Organization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | NICE | CCO | ASCRS | NCCN | ESMO |

| Body Responsible | Guideline Development Group |

Program in Evidence Based Care |

Standards Practice Task Force |

Rectal Cancer Panel |

Guideline Working Group |

| Multidisciplinary | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Patient advocate | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Funding source | Government | Government | Specialty society |

Specialty society |

Specialty society |

| Year published | 2011 | 2008–2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2013 |

|

Time-frame for literature review |

1806–2011 | 1999–2011 | Through 2/2012 |

N/A | N/A |

|

Rectal cancer CPGs distinct from colon cancer |

No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Document length, pages | 186 | 211 | 16 | 110 | 8 |

| Number of references | 245 | 206 | 154 | 486 | 40 |

|

Number of references shared with NICE |

[ref] | 10 | 11 | 10 | 6 |

| % of references from RCTs | 21% | 14% | 18% | 13% | 35% |

| Disclosure statement | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Updating strategy | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Dissemination | Online | Journal & online |

Journal & online |

Journal, online, & mobile app |

Journal & online |

(ASCRS: American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, CCO: Cancer Care Ontario, ESMO: European Society of Medical Oncology, NCCN: National Comprehensive Cancer Network, NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, RCT: Randomized controlled trials).

Although the guidelines were developed during similar time periods, the evidence used to develop and justify treatment recommendations differed. For example, the number of references ranged from 40 to 384 citations per CPG. The methods for developing the CPGs specifically included systematic reviews in the ASCRS, CCO, and NICE guidelines, but ESMO and NCCN do not report using systematic literature reviews as a part of their process.

Guideline Development: AGREE II Scores

The AGREE II scores for each CPG in all six domains are shown in Figure 1. Overall, rectal cancer CPGs from NICE had the highest mean AGREE II score of 90% (range by CPG; 27% – 90%). In the scope & purpose domain, only CCO and NICE clearly defined their scope, global objectives, and target populations. For the stakeholder involvement domain, only NICE and NCCE included patients, their representatives, and other stakeholders in the development of CPGs. The biggest differences were seen in the rigor of development domain, with the NICE CPG scoring a 96% compared to 17% for the ESMO guideline. Scores for the clarity of presentation domain were generally high in all CPGs. In general, there was little information regarding potential organizational barriers, cost implications, and tools for application across all CPGs making the scores for the applicability domain the lowest across all guidelines. Lastly, only CCO and NICE CPGs included clear information about the potential conflicts of interest of guideline institutions or members as presented in the editorial independence domain scores.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the quality of the clinical practice guidelines using the AGREE II instrument. (ASCRS: American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, CCO: Cancer Care Ontario, ESMO: European Society of Medical Oncology, NCCN: National Comprehensive Cancer Network, NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence).

Guideline Content: Scientific Agreement

The 21 processes of care are compared in Table 2. Overall, the five CPGs had uniform agreement on their recommendations in only 8 of the 21 (32%) processes of care, as described below. Of the 13 processes with disagreement, 6 recommendations were in direct conflict, and 7 were actually non-recommendations, reflecting a lack of direct recommendations on a given issue.

Table 2.

Scientific content comparison between clinical practice guidelines.

| Recommendations | NICE | CCO | ASCRS | NCCN | ESMO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis and Staging | |||||

| Thorough history and physical exam, rigid proctoscopy, CEA | • | • | • | • | • |

| Complete preoperative colonoscopy with biopsy | • | • | • | • | • |

| CT colonography as an alternative to colonoscopy | • | • | • | ||

| Staging CT of Chest, Abdomen and Pelvis, no additional staging imaging | • | • | • | ||

| Pelvic MRI for all patients | • | • | |||

| Recommend against routine PET imaging | • | • | • | • | |

| Preoperative enterostomal therapist consult | • | • | • | ||

| Preoperative Management | |||||

| Discuss RC patients in a multidisciplinary tumor board | • | • | • | • | • |

| Do not offer neoadjuvant therapy for low-risk resectable RC | • | • | • | • | • |

| Consider SCRT with immediate surgery for moderate-risk RC | • | • | |||

| Consider LCCRT with interval surgery for borderline moderate-high risk | • | • | • | • | • |

| Offer LCRRT with interval surgery for high risk operable cancer | • | • | • | • | • |

| Operative Management | |||||

| Offer local excision when feasible for low risk T1 tumors with further therapy if high risk features or compromised margins | • | • | • | • | • |

| Recommend laparoscopic surgery as an alternative to open surgery for patients suitable for both, and surgeons are appropriately trained | • | • | |||

| Adjuvant Therapy | |||||

| Assess pathologic staging after surgery before deciding whether to offer adjuvant therapy | • | ||||

| Offer adjuvant chemotherapy to patients who had surgery alone or had SCRT without chemotherapy | • | • | • | • | • |

| Offer adjuvant chemotherapy in all patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy or LCCRT | • | • | • | • | |

| Surveillance | |||||

| Start surveillance 4–6 weeks after potentially curative intervention | • | ||||

| Minimum 2 CT scans of the chest, abdomen and pelvis in the first 3 years and CEA every 6 months for the first 3 years | • | • | • | ||

| Offer surveillance colonoscopy at 1 year; if normal repeat in 5 years | • | • | • | • | |

| Stop surveillance when patient and physician agree that the benefit no longer outweighs risk of tests, or patient cannot tolerate further therapy | • | • |

A solid circle (•) denotes agreement in scientific content to the stated recommendation, a blank means that the guideline objectively disagrees or fails to mention the given recommendation. Note ASCRS does not have surveillance recommendations published after 2008. (ASCRS: American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, CCO: Cancer Care Ontario, ESMO: European Society of Medical Oncology, NCCN: National Comprehensive Cancer Network, NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, CEA: Carcino-embryonic antigen, SCRT: Short course radiation therapy, LCCRT: Long course chemo-radiation therapy).

Diagnosis and Staging

Whereas all other CPGs defined rectal cancer as a tumor located up to 15 cm from the anal verge on rigid proctoscopy thereby dividing the rectum into thirds, NCCN differed in its definition by limiting it to tumors 12 cm from the anal verge. While all CPGs recommend a complete preoperative colonoscopic evaluation, only ASCRS, ESMO and NICE mention the role of CT colonography as an alternative. ASCRS, NCCN and NICE CPGs recommend a CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis for staging, but CCO and ESMO recommend an initial chest X-ray, and ESMO recommends an abdominal ultrasound or MRI to assess for liver metastases.

Preoperative Therapy

All CPGs acknowledge the need for a multidisciplinary tumor board for the management of rectal cancer patients and that preoperative chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy are not indicated in low-risk or stage I resectable rectal cancer patients. The comparison highlights the differences in practice between North America and Europe in the use of short course radiation therapy for moderate-risk rectal cancer patients. However, all CPGs recommend preoperative long course chemo-radiation therapy for high-risk or advanced stage patients.

Operative Management

All CPGs advise for the use of local excision techniques for low risk/stage I rectal cancer, and recommend further treatment if high-risk features are present on histopathology. Only ASCRS and NICE recommend laparoscopic rectal surgery as an alternative to the open approach. The NCCN discusses the role of laparoscopic surgery but recommends its use only in the context of a clinical trial, and CCO and ESMO do not specifically discuss the role of laparoscopic surgery.

Adjuvant Therapy

All other CPGs disagree with the NICE statement that the postoperative pathological staging is more important than the preoperative clinical staging in deciding whether to administer postoperative chemotherapy. All CPGs agree that patients with locally advanced or node positive rectal cancers who did not receive preoperative chemotherapy should receive postoperative chemotherapy. However, the CPGs differed in their interpretation of evidence regarding indications for postoperative chemotherapy among patients who received preoperative chemoradiation. Although all CPGs reference the same publication by Bossett and colleagues,23 NICE does not make a recommendation due to insufficient evidence; CCO and NCCN acknowledge the lack of evidence but recommend adjuvant therapy based on expert consensus; ASCRS strongly recommends adjuvant therapy and grades the evidence as Level 1A; and ESMO recommends adjuvant therapy and grades the evidence as Level 2B. Of note, ASCRS also cites an additional subgroup analysis on this topic;24 however, a subgroup analysis does not meet criteria for level 1A evidence and the authors of that study appropriately caution that their analysis is exploratory in nature.25

Surveillance

Only the NICE CPG clearly defined when surveillance begins and ends. While NICE, CCO and NCCN recommend routine interval CT scans and CEA measurements, ESMO reserves radiological and laboratory tests for symptomatic patients only. ASCRS did not include surveillance in this CPG version.

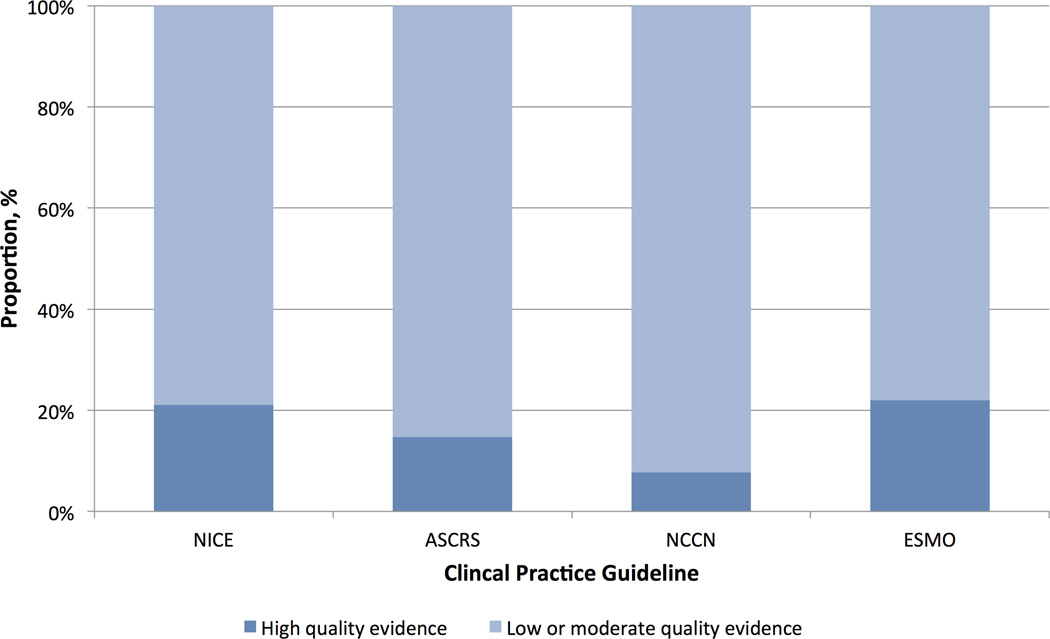

Quality of Evidence

In all CPGs, the majority of evidence used to synthesize the recommendations was of low-moderate quality (Figure 2). High quality evidence (as graded by the authoring organizations) only comprised 22% of citations. The guidelines appeared to use a varied evidence base despite a similar time-frame for searching the evidence base. Using the citations in the NICE CPG (which includes 245 references) as the benchmark, the other documents only had six to 11 references in common with NICE.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the quality of evidence cited within each clinical practice guideline. Note: Cancer Care Ontario (CCO) does not separately grade the evidence, and is therefore not included. (ASCRS: American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, ESMO: European Society of Medical Oncology, NCCN: National Comprehensive Cancer Network, NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence).

DISCUSSION

This study sought to evaluate the quality and scientific content of CPGs and compare the scientific basis for guidelines issued by various organizations. Using a validated guideline appraisal instrument, we identified wide differences in the quality of guideline development and reporting for CPGs, with overall scores ranging from 26 to 90%. The majority of the evidence that comprised CPGs was of low to moderate quality, and there were substantial differences in interpretation of data. There were conflicting recommendations in 13 of the 21 specific processes of care for rectal cancer that we examined.

We previously reported that oncology CPGs failed to meet the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) standards for guideline development.6 The present study demonstrates that these inadequacies in development herald important differences in the scientific content and the synthesized recommendations contained within CPGs. While it is well known that there is a relative paucity of high-quality evidence and randomized controlled trials in cancer care, an end user might expect that CPGs would examine the best available evidence and draw similar conclusions. We found, however, that in spite of “systematic reviews” of the literature in three widely used CPGs, there were only 6–11 shared reference citations with the highest rated CPG. Further, even when using the same studies, CPGs interpreted their conclusions differently, assigned them differing levels of evidence quality, and formulated conflicting recommendations. It is important that CPGs be transparent in their methodology, clearly outlining areas where evidence is insufficient and where expert opinion has been used. For example, NICE and CCO are exemplars in this regard, as their CPGs identify gaps in evidence and explicitly state when a recommendation is based on expert opinion. Consensus statements may be appropriate where evidence is lacking; however, some recommendations within different CPGs are written with a degree of certainty that may be unwarranted given the lack of strong evidence, leaving clinicians without reliable guidance.

There are differences in how organizations develop guidelines. For example, the two highest scoring CPGs were authored by government-related organizations in countries with nationally funded health systems. This is not surprising since broad-reaching policy decisions about resource allocations for treatment warrant higher quality guidelines. Further, the composition of the CPG development groups varied considerably. Some included experts in a single specialty while others encompassed multiple specialties; some panels included patient advocates. This may certainly influence what is included in the CPG documents based on stakeholders’ perspectives. Even in panels with a multi-disciplinary structure, access to the necessary methodological skills may have been limited. This highlights the possible lack of adoption of a standardized CPG development process and raises the question of whether greater oversight is needed in this regard.

Generally speaking, CPGs with high scores on the quality appraisal instrument performed consistently well in most other domains, except for the applicability domain, where most CPGs fell short. Lack of applicability could mean that despite the vast resources that are invested into developing CPGs, little consideration is given to how recommendations will be translated into practice. More efforts may be needed to focus on understanding barriers to the implementation of guidelines and how to better use evidence to inform decision-making and treatment planning.

Because of increasing pressures to practice evidence-based medicine and adhere to standards of care, CPGs have become an increasingly important resource for clinicians. However, the quality of the development process of the guidelines is highly variable. More importantly, the content of the resultant recommendations themselves are variable, and it is possible that clinicians’ modest uptake of guideline recommendations is directly related to perceptions that CPGs are not of sufficient quality. The downstream implications for measurement and possible enforcement of concordance to guideline recommendations, as well as continued variation in patient outcomes, are important to consider in this context.

While the present study did not specifically address the effect of the conflicting CPGs on practice patterns, there is growing evidence that differences in practice are present even when CPGs are in full agreement on a specific recommendation. For example, Monson and colleagues26 recently investigated variation in preoperative therapy for stage II/III rectal cancer patients and found suboptimal adherence to this recommendation, with significant differences based on hospital volume and geographic regions. The present study highlights some potential additional reasons for lack of adherence to guidelines including the lack of a unified CPG development process, conflicting recommendations, and poor applicability of the produced CPGs.

This study has several limitations. By intent, the analysis presented herein does not address rectal cancer guidelines by all societies or organizations. CPGs that were not included may perform better or worse on the quality appraisal instrument, but the comparison was limited to those that are the most frequently used in clinical care and our findings are actually more likely to be generalizable because of that. We did not examine guidelines for a wide range of disease sites because of our focus on exact recommendations for specific processes of care, and rectal cancer is an ideal example of the complex interplay between multiple disciplines. Even though the study is limited in this regard, it is probable that oncology CPGs for different disease sites face similar challenges in their development and have similar deficiencies in evidence interpretation and scientific content. Further, we relied on materials reported in the published versions of the CPGs, our findings could be affected not only by the quality of the guidelines themselves, but also by the quality of the reporting process. Nonetheless, this also potentially puts the quality of the reporting process under scrutiny.

In conclusion, there is significant variation in CPG development processes, with associated differences in scientific content and interpretation of evidence, resulting in conflicting recommendations. These differences mean that there may be no comprehensive resource available to guide healthcare providers, which may limit the delivery of high quality evidence-based cancer care. Clinicians are advised to be aware of potential gaps in evidence and conflicting recommendations when using CPGs. If CPGs are to be confidently used as standards of care going forward, guideline developers bear the burden of evaluating both their processes and resultant end product, based on endorsed standards for the development of high-quality guidelines.

Acknowledgments

Funding statement: ZMA is supported by AHRQ T32 HS000053-22. SH is supported by NIH/NCI 1K07 CA163665-22. SLW is supported by AHRQ 1K08 HS20937-01.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no disclosures to make.

Previous presentation: This work was presented in part as a podium presentation at the Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Meeting in March 2014 (Phoenix AZ)

REFERENCES

- 1.Grilli R, Magrini N, Penna A, Mura G, Liberati A. Practice guidelines developed by specialty societies: the need for a critical appraisal. Lancet. 2000;355(9198):103–106. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458–1465. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenberg CC, Lipsitz SR, Neville B, et al. Receipt of appropriate surgical care for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. Arch Surg. 2011;146(10):1128–1134. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sox HC. Assessing the trustworthiness of the guideline for management of high blood pressure in adults. JAMA. 2014;311(5):472–474. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reames BN, Krell RW, Ponto SN, Wong SL. Critical evaluation of oncology clinical practice guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(20):2563–2568. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.8371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kung J, Miller RR, Mackowiak PA. Failure of clinical practice guidelines to meet institute of medicine standards: Two more decades of little, if any, progress. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(21):1628–1633. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham R, Mancher M, Wolman D. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2011. pp. 1–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levit L, Balogh E, Nass S, Ganz PA. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care : Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monson JRT, Weiser MR, Buie WD, et al. Practice parameters for the management of rectal cancer (revised) Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56(5):535–550. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31828cb66c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith AJ, Driman DK, Spithoff K, et al. Optimization of Surgical and Pathological Quality Performance in Radical Surgery for Colon and Rectal Cancer : Margins and Lymph Nodes Optimization of Surgical and Pathological Quality Performance in Radical Surgery for Colon and Rectal Cancer : Margins a. Toronto: Program in Evidence-Based Care; 2013. pp. 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Earle C, Annis R, Sussman J, Haynes AE, Vafaei A. A Quality Initiative of the Program in Evidence-based Care ( PEBC ), Cancer Care Ontario Follow-up Care , Surveillance Protocol , and Secondary Prevention Measures for Survivors of Colorectal Cancer A Quality Initiative of the Program in Evidence-based Ca. Program in Evidence-Based Care; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan K, Welch S, Raifu AO. PET Imaging in Colorectal Cancer. Program in Evidence-Based Care; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong R, Berry S, Spithoff K, et al. Preoperative or Postoperative Therapy for the Management of Patients with Stage II or III Rectal Cancer Preoperative or Postoperative Therapy for the Management of Patients with Stage II or III Rectal Cancer : Guideline Recommendations. Program in Evidence-Based Care; 2011. pp. 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glimelius B, Tiret E, Cervantes A, Arnold D. Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(Suppl 6):vi81–vi88. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt240. (Supplement 6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.NCCN. Practice Guidelines in Oncology - Rectal Cancer. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Colorectal Cancer : The Diagnosis and Management of Colorectal Cancer. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):E839–E842. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO Handbook for Guideline Development. World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van de Ven AH, Delbecq AL. The nominal group as a research instrument for exploratory health studies. Am J Public Health. 1972;62(3):337–342. doi: 10.2105/ajph.62.3.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raine R, Sanderson C, Hutchings A, Carter S, Larkin K, Black N. An experimental study of determinants of group judgments in clinical guideline development. Lancet. 364(9432):429–437. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16766-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arriaga AF, Lancaster RT, Berry WR, et al. The better colectomy project: association of evidence-based best-practice adherence rates to outcomes in colorectal surgery. Ann Surg. 2009;250(4):507–513. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b672bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bosset J-F, Collette L, Calais G, et al. Chemotherapy with preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(11):1114–1123. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collette L, Bosset J-F, den Dulk M, et al. Patients with curative resection of cT3-4 rectal cancer after preoperative radiotherapy or radiochemotherapy: does anybody benefit from adjuvant fluorouracil-based chemotherapy? A trial of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Rad. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(28):4379–4386. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.9685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minsky BD. Adjuvant management of rectal cancer: the more we learn, the less we know. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(28):4339–4340. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.8892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monson JRT, Probst CP, Wexner SD, et al. Failure of evidence-based cancer care in the United States: the association between rectal cancer treatment, cancer center volume, and geography. Ann Surg. 2014;260(4):625–632. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]