Abstract

Most genome-wide association studies have explored relationships between genetic variants and plasma phospholipid fatty acid proportions, but few have examined apparent genetic influences on the membrane fatty acid profile of red blood cells (RBC). Using RBC fatty acid data from the Framingham Offspring Study, we analyzed over 2.5 million single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for association with 14 RBC fatty acids identifying 191 different SNPs associated with at least 1 fatty acid. Significant associations (p<1×10−8) were located within five distinct 1 MB regions. Of particular interest were novel associations between (1) arachidonic acid and PCOLCE2 (regulates apoA-I maturation and modulates apoA-I levels), and (2) oleic and linoleic acid and LPCAT3 (mediates the transfer of fatty acids between glycerol-lipids). We also replicated previously identified strong associations between SNPs in the FADS (chromosome 11) and ELOVL (chromosome 6) regions. Multiple SNPs explained 8–14% of the variation in 3 high abundance (>11%) fatty acids, but only 1–3% in 4 low abundance (<3%) fatty acids, with the notable exception of dihomo-gamma linolenic acid with 53% of variance explained by SNPs. Further studies are needed to determine the extent to which variations in these genes influence tissue fatty acid content and pathways modulated by fatty acids.

Keywords: PUFA, apoA-I maturation, oleic acid, linoleic acid, arachidonic acid, glycerol-lipids

1. Introduction

Red blood cell (RBC) proportions of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids have well established relationships with a variety of disease phenotypes and risk factors, including total mortality [1], acute coronary syndrome [2,3], serum lipid levels [4], inflammatory markers [5], cognitive function [6] and brain size [7,8] among others. Variation in RBC omega-3 fatty acid levels (i.e., proportions, expressed as a percent of total fatty acids) have been shown to possess a strong heritable component [4,9], suggesting that not only dietary but also genetic factors likely play an important role in explaining differences between individuals [10,11].

Recently genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have sought to identify common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with fatty acid levels. Initial investigations have focused on establishing potential relationships between plasma phospholipid fatty acid proportions and common SNP variations [12–15]. However, mounting evidence suggests that this fatty acid pool may be more affected by recent fat consumption [16], potentially obscuring the role of genetic variation in determining fatty acid composition [4,17].

Here we report a GWAS exploring relationships between the relative proportions of fourteen saturated, mono- and polyunsaturated RBC fatty acids with over 2.5 million common (minor allele frequency >1%) SNPs in the Framingham Heart Offspring Study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Sample

Our analysis focused on the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) Offspring sample, a population based longitudinal study of families living in Framingham, Massachusetts. Detailed descriptions of the sample are available [4,18–20]. The final sample for this study consisted of 2633 individuals for whom both fatty acid and genotype data were available. The 2633 is a subset of 2899 Offspring subjects attending Examination 8 (2005–2008); those excluded due to missing genotype data had similar demographic and fatty acid profiles as those included in the study (data not shown). Written informed consent was provided by all participants, and the Institutional Review Board at the Boston University Medical Center approved the study protocol.

2.2 Fatty acid measurements

The fatty acid composition of RBC samples were analyzed by gas chromatography equipped with a SP 2560 capillary column after direct transesterification for 10 minutes in boron trifluoride/methanol and hexane at 100 C as previously described. [4]. This technique generates fatty acids primarily from RBC glycerophospholipids. All fatty acids with at least 0.5% abundance were included for analysis (except trans oleic acid): arachidonic acid (AA), dihomo-gamma-linoleneic acid (DGLA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), docosapentaenoic acid-n3 (DPA-n3), docosapentaenoic acid-n6 (DPA-n6), docosatetraenoic acid (DTA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), linoleic acid (LA), oleic acid (OA), palmitic acid (PA), and stearic acid (SA). Three fatty acids below the 0.5% abundance level were also included: Palmitoleic acid (POA), because it is a marker of de novo lipogenesis [21]; gamma-linolenic acid (GLA), because it is the initial product of LA metabolism via delta-6 desaturase [22]; and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), because as a dietary essential fatty acid like LA, its levels should be under less metabolic control than fatty acids that are the products of metabolism. Means and SDs of all 14 FAs are provided in Supplemental Table 1.

2.3 Genotype data

This analysis is based on approximately 2.5 million autosomal CEU (Centre d’Etude du Polymorphisme Humain collection from Utah; Northern and Western European ancestry) HapMap SNPs which were measured directly (approximately 550,000) or imputed (approximately 2 million) as previously reported [18]. Briefly, direct genotypes were obtained using the Affymetrix 500K and MIPS 50K chips, and were analyzed at the Affymetrix Core Laboratory. SNPs with missing data rates more than 3%, Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium p-values less than 1×10−6, more than 100 Mendelian errors or low minor allele frequency (less than 1%) were eliminated from consideration. Measured SNPs, along with HapMap (release 22, build 36, CEU reference panel) [23] was used to impute the remaining 2 million SNPs using MaCH [24]. Quality control procedures were similar for both imputed and directly measured SNPs, with the addition of standard imputation quality metrics for imputed SNPs (see [18] for details).

2.4 Statistical analysis

For each of the 14 fatty acids considered here, a linear mixed model was fit for each of the 2.5 million SNPs which passed the initial quality control criteria. Each regression model predicted log10 -transformed fatty acid level by SNP genotype (number of minor alleles), adjusting for age, sex and a random covariance component summarizing the family-structure present in the Framingham data set (i.e. matrix of kinship coefficients). We reported partial r2 values in the text, which were percent change in the log of the relative fatty acid proportion explained by one additional minor allele (i.e. additive genetic model). Linear mixed effects models using the kinship matrix were run using R (lmekin function) for all analyses [25]. SNPs were considered genome-wide significant if their p-value was less than 1×10−8. For each fatty acid, the distribution of p-values was evaluated using a Q-Q plot, and the genomic control lambda value (λGC) was estimated. λGC values ranged between 0.996 and 1.067 for the 8 fatty acids with at least one SNP reaching genome-wide significance (p<1×10−8), showing little evidence for over-inflation of test statistics [26]. A final model for each fatty acid was also computed which adjusted for age, sex and kinship, as well as all significant SNPs, after eliminating SNPs showing strong pairwise correlations (Pearson correlation above 0.7 between genotypes) with other SNPs in the model.

3. Results

The clinical characteristics for the FHS Offspring participants and their fatty acid levels have been previously reported [4]; briefly they had a mean (SD) age of 66 (9) years, 54% were female, 9% smoked, and nearly half were treated for hypertension (49%) and high cholesterol (43%). They also had the following comorbidities: diabetes (14%), coronary heart disease (11%), and congestive heart failure (3%).

In all, 470 linear mixed models of SNP-fatty acid combinations reached a genome-wide significant p-value of less than 1×10−8 (Supplemental Table 2). Since some SNPs were related to multiple fatty acids, there were a total of 191 different (i.e., uniquely associated) SNPs reaching genome-wide significance for at least one fatty acid (see Supplemental Table 3). In general, when multiple fatty acids were associated with the same SNP, the fatty acids were correlated (details not shown), in part because they are often in the same metabolic pathway. Six of the fatty acids in our analysis had no SNPs reach the genome-wide significance level (DHA, DPA-n6, EPA, PA, POA and SA all 1×10−8 < p-value <1×10−6), but eight of the fatty acids contained at least one genome-wide significant SNP (see Supplemental Figures 1a–1h for Manhattan plots of these eight fatty acids).

As expected, many of the 191 uniquely associated SNPs occur in close proximity to each other [i.e., within a 1 mega-base (MB) region], and so we summarized the 191 unique associations by focusing on five distinct 1MB or smaller regions which contained all 191 uniquely associated SNPs. Table 1 provides an overview of the five associated regions, summarizing location information, the number of significantly associated SNPs, references to prior literature about the functionality of the region and a listing of the associated fatty acids.

Table 1.

Summary of genome-wide association results

| Chr | Size of region (kb) | Location (kb) | # sig. SNPs1 | Genes containing SNPs | Prior GWAS evidence?2 | Plausible biological mechanism to alter fatty acid level | Smallest p-value (rs#; r2: Fatty Acid) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 246106 | 1 | TRIM58 | Yes [27–29] | Unknown | 5×10−11 (rs3811444; 0.016: OA) |

| 3 | 27 | 144090–144117 | 3 | PCOLCE2 | No | Regulator/Modulator of apoA-I | 1×10−10 (rs6778966 0.016: AA) |

| 6 | 46 | 11114–11068 | 13 |

SYCP2L ELVOL2 |

Yes [12,13,42,43] | Elongation of n3-DPA to DHA | 1×10−10 (rs3798707; 0.012: DPA-n3) |

| 11 | 488 | 61120–61608 | 141 |

DAGLA C11orf10 C11orf9 FEN1 FADS1 FADS2 FADS3 RAB3IL1 BEST1 |

Yes [12,13]3 | Desaturation of fatty acids | 3×10−305 (rs174601; OA: 0.017, LA: 0.058, ALA: 0.012, DGLA: 0.35, AA: 0.122, DPA-n3: 0.024) |

| 12 | 112 | 6940–7051 | 33 |

PTPN6 PHB2 LPCAT3 (alt. MBOAT5) C1S |

No | Mediates the transfer of fatty acids between glycerol-lipids | 3×10−49 (rs2110073; OA: 0.079, LA: 0.039) |

All 191 SNP IDs are provided in Supplemental Table 3

Based on search at http://www.genome.gov/gwastudies/

Among many others

3.1 Chromosome 1

The single significant SNP in chromosome 1 (rs3811444) is located in TRIM58 (tripartite motif containing 58), a gene located in 1q44 from base pair (bp) 248,020,501 to 248,043,440. SNP rs3811444 is a C (common allele) to T (rarer allele) polymorphism, with T alleles associated with lower levels of OA (partial r2 =1.6%).

3.2 Chromosome 3

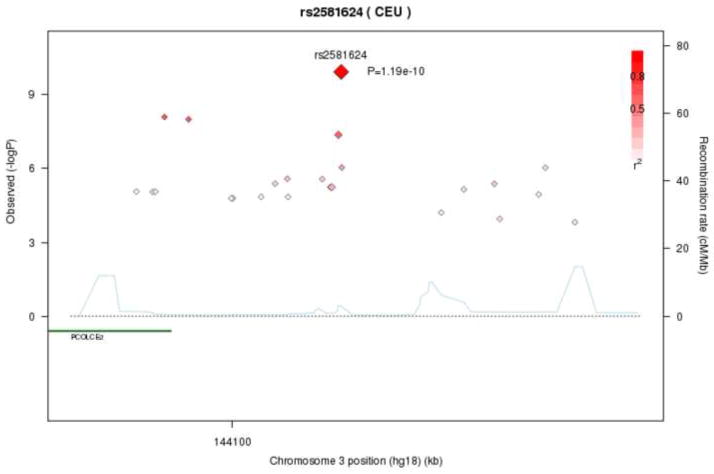

Three SNPs in and nearby to the PCOLCE2 (alt: PCPE2; procollagen C-endopeptidase enhancer 2) gene were significantly associated with AA levels (rs2248811, rs6778966, rs2581624) with p-values ranging from 8×10−9 to 1.2×10−10. All three significant SNPs have similar minor allele frequencies (~0.20), and yielded similar explanatory power for AA (partial r2 values of 1.3 to 1.6%). PCOLCE2 starts at bp 142,536,702 and ends at 142,608,045 on chromosome 3. One of the three significant SNPs (rs2248811) is located within an intron in PCOLCE2 (at 142,606,942), with the other two SNPs located downstream (rs6778966 at 142,610,610; rs2581624 at 142,633,869). Little prior GWAS evidence exists involving SNPs in PCOLCE2. Figure 1 depicts the regional association of AA on chromosome 3 near PCOLCE2, showing that three significant SNPs are highly correlated. Table 2 shows that rs2581624 explained 1.6% of the change in AA.

Figure 1.

Regional association plot of PCOLCE2 locus with Arachidonic Acid (AA) levels. Correlations between the target SNP (rs2581624; the SNP with the lowest p-value (1.19×10−10)) and nearby SNPs (within a 500kb) region are highlighted. Genotypes at rs2581624 are highly correlated with both rs2248811 (intergenic) and rs6778966 (intra-genic), both of which also reach genome-wide significance (−logP>8). r2 values were based on the HapMap CEU population.

Table 2.

Variation in fatty acids explained by significant SNPs

| Strongest single SNP association1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr | Fatty Acid | Gene | rs# | Minor allele | Partial r2 | Standardized beta |

| 1 | OA | TRIM58 | rs3811444 | T | 0.016 | −0.13 |

| 3 | AA | PCOLCE2 | rs2581624 | C | 0.016 | −0.13 |

| 6 | DPA-n3 | ELOVL2 | rs8523 | A | 0.013 | 0.11 |

| 11 | DGLA |

FADS1 C11ORF9 |

rs174548 rs509360 |

G A |

0.418 0.200 |

0.65 −0.45 |

| 12 | LA OA |

LPCAT3 PHB2 |

rs12580543 rs2110073 |

C T |

0.044 0.079 |

0.21 −0.28 |

The SNP-FA with the largest partial r2, i.e. proportion of variability in the fatty acid explained by changes in the SNP genotypes adjusted for age and gender, in the region. Estimated from the age and sex adjusted model. In cases where there were SNPs with opposite direction effects the strongest positively and the strongest negatively associated SNPs are reported.

3.3 Chromosome 6

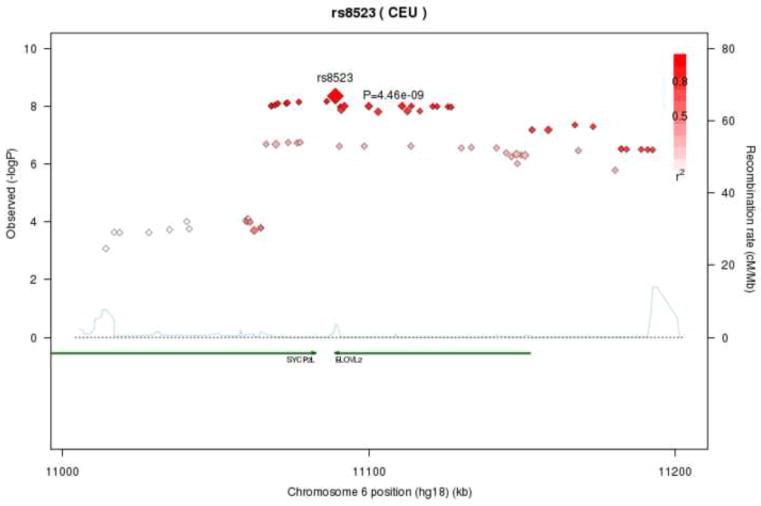

Thirteen SNPs within a 46kb region of chromosome 6 were significantly related to DPA-n3 levels. This region contains two genes: SYCP2L (synaptonemal complex protein 2-like) and ELOVL2 (ELOVL fatty acid elongase 2), which are located from 10,887,064 to 10,974,542 and 10,980,992 to 11,044,624, respectively. Seven of the significant SNPs were contained within SYCP2L, five within ELOVL2 and one in the intergenic space between the two genes. All significantly associated SNPs in this region had similar explanatory power (partial r2 values between 1.2 and 1.3%). Figure 2 illustrates that the genome-wide significant SNPs in the ELOVL2-SYCP2L region are in linkage disequilibrium.

Figure 2.

Regional association plot of ELOVL2-SYCP2L locus with Docosapentaenoic Acid-n3 (DPA-n3) levels. Correlations between the target SNP (rs8523; the SNP with the lowest p-value (4×10−9)) and nearby SNPs (within a 500kb) region are highlighted, showing strong correlations between genome-wide significant SNPs in this region. r2 values were based on the HapMap CEU population.

3.4 Chromosome 11

The majority of 141 associated SNPs on chromosome 11 were contained within a 488kb region of chromosome 11. This region contains nine distinct genes, with many of the genes (FADS2, FADS1, FEN1, C11ORF9 and C11ORF10) showing associations with approximately half of the fatty acids in our analysis. The remaining genes (BEST1, RAB3IL1, FADS3 and DAGLA) show associations with between one and three fatty acids (see Table 2 for details). Full results are provided in Supplemental Table 3 which provides p-values, minor allele frequencies and effect size estimates for the SNPs in the region. We briefly describe three distinct subregions.

Our analysis identifies twenty-nine significant SNPs in the region in and upstream of DAGLA (Diacylglycerol lipase, alpha; bp 61,119,554 to 61,273,052), showing associations with DGLA levels for all SNPs, plus with AA for two of the twenty-nine SNPs. Associations with DGLA levels were generally negative, though some SNPs showed positive association (partial r2 between 1.7 and 3.4%; see Supplemental Table 3 for details).

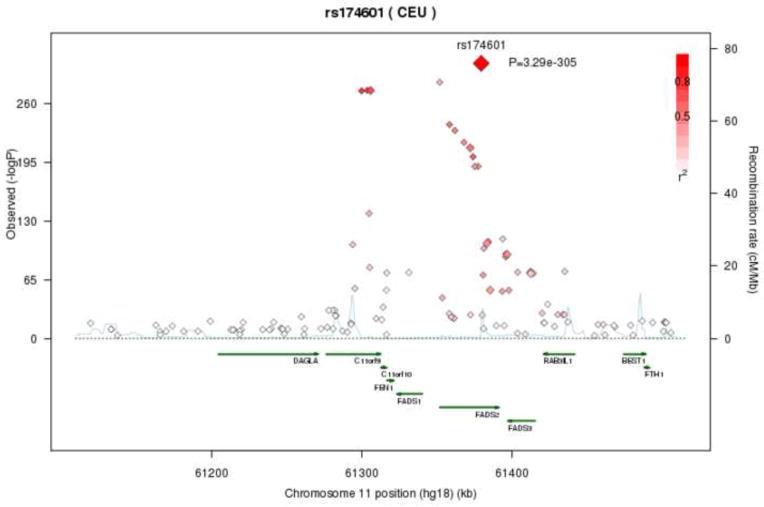

The FADS genes (FADS1; FADS2; FADS3; fatty acid desaturase), along with nearby ORFs (C11ORF9, FEN1 and C11ORF10) contain or are nearby to 86 significant SNPs, with most SNPs associated with multiple FA, and widely varied direction and magnitude of effect (see Supplemental Table 3 for details). Figure 3 shows the high correlation between associated SNPs throughout the FADS region. Table 2 shows that SNPs in this region accounted for as much as 42% of the variability in DGLA levels.

Figure 3.

Regional association plot of FADS locus with Dihomo-gamma-linoleic acid (DGLA) levels. Correlations between the target SNP (rs174601) and nearby SNPs (within a 500kb) region are highlighted, showing strong correlations between genome-wide significant SNPs in this region between C11orf9 and FADS3, with less association with SNPs in DAGLA and BEST1. r2 values were based on the HapMap CEU population.

Remaining SNPs near or contained in RAB3IL1 (RAB3A interacting protein; 13 SNPs) and within or downstream of BEST 1 (Bestrophin 1) were mainly positively associated with DGLA levels, with a handful of SNPs also related AA and LA levels (see Supplemental Table 3 for details).

3.5 Chromosome 12

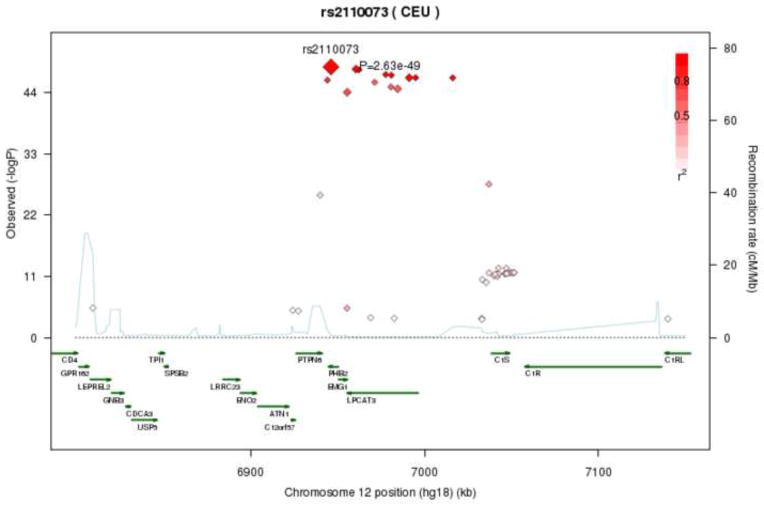

All 33 significant SNPs on chromosome 12 are within a single 112 kb region which contains multiple genes (PTPN6, PHB2, MBOAT5 (alt. LPCAT3) and C1S). These SNPs all show association with OA and LA. Rare alleles were generally associated with lower OA levels and higher LA levels, corresponding to the negative association between these two fatty acids in the sample. Figure 4 illustrates the regional association for OA, showing strong correlation between the genotypes of significant SNPs in this region (a similar effect is observed for significant LA SNPs in this region). SNPs in this region accounted for as much as 4–8% of variation in LA and OA levels (see Table 2).

Figure 4.

Regional association plot of LPCAT3 locus with Oleic Acid (OA) levels. Correlations between the target SNP (rs2110073) and nearby SNPs (within a 500kb) region are highlighted, showing strong correlations between genome-wide significant SNPs in this region. r2 values were based on the HapMap CEU population.

3.6 Multivariable models

Table 3 illustrates the overall variation explained (model r2) for each of the eight fatty acids with at least one genome-wide significant SNP. In particular, a separate model predicting the log-transformed fatty acid relative proportion for each of the eight fatty acids was predicted by age and sex, and then all significant SNPs for the fatty acid were added to the model. In cases where SNPs showed strong association with each other (Pearson correlation between genotypes greater than 0.7), only one individual SNP from that group was added to the model. The model predicting DGLA had the largest overall variability explained (53.5%), and only 0.1% of this estimate was associated with age and sex. Models predicting AA, LA and OA explained 13.7%, 10.5% and 8.3% of the variation in the relative proportions of these fatty acids, respectively, with all three models showing large improvements over models containing only age and sex (13.6%, 8.9% and 7.8% improvement, respectively). Models for ALA and DTA explained similar amounts of overall variation (8.9% and 9.9%), but were driven largely by age and sex and not SNP genotypic variation (1% and 1.6% improvement with SNP genotypes). Finally, models for GLA and DPA-n3 explained less variation overall (6.1% and 6.4%), with approximately two-thirds of the variation explained by age and sex (1.5% and 2.6% improvement with SNP genotypes).

Table 3.

Total variation in fatty acids explained by significant SNPs (model r2)

| r2 of Multivariable models | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty Acid | Age+Sex Only | Age+Sex+ All Significant SNPs1 | Additional variance explained by SNP |

| AA | 0.1% | 13.7% | 13.6% |

| ALA | 7.9% | 8.9% | 1.0% |

| DGLA | 0.1% | 53.5% | 53.4% |

| DTA | 8.3% | 9.9% | 1.6% |

| GLA | 4.4% | 6.1% | 1.7% |

| LA | 1.6% | 10.5% | 8.9% |

| OA | 0.5% | 8.3% | 7.8% |

| DPA-n3 | 3.8% | 6.4% | 2.6% |

After eliminating highly correlated SNPs, so that genotypes between all pairs of genome-wide significant SNPs in the model have pairwise Pearson correlation coefficients less than 0.7

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This report presents the results of the largest genome-wide association study of RBC fatty acid composition to date. In our exploration of potential associations between 14 fatty acids and 2.5 million SNPs, we identified five distinct regions yielding associations reaching genome-wide significance. Of these, two of the regions replicated prior results from genome-wide association studies GWAS of serum fatty acid levels (Chromosome 6 (ELOVL2); Chromosome 11 (FADS genes)), two were novel (Chromosome 3 (PCOLCE2) and Chromosome 12 (LPCAT3)) and one identified a SNP on Chromosome 1 (TRIM58) with prior evidence of association to platelet and RBC counts. We briefly discuss each of these distinct regions in light of their known biology and prior GWAS evidence.

4.1 TRIM58

TRIM58 contains only a single significant SNP-fatty acid association. However, this SNP was recently identified as significantly related to platelet [27] and RBC counts [28] in European populations. The TRIM58 gene has also been associated with mean corpuscular volume in a Japanese sample [29]. Despite prior association evidence with related phenotypes, its function has no clear relationship with fatty acid metabolism. In addition, previous studies with fish oils have not shown effects on platelet counts [30] (except with supraphysiological intakes [31]), but do affect platelet function [e.g., aggregation [32,33], thrombin generation [34], activation].

4.2 PCOLCE2

To date fatty acid GWAS have not uncovered associations with SNPs in PCOLCE2. PCOLCE2 encodes the protein PCPE2 [35] which regulates apoA-I maturation [36], modulating apoA-I levels [37]. ApoA-I is the major structural component of high density lipoproteins (HDL). While its role in reverse cholesterol transport is well known, HDL also transports a large portion of plasma phospholipids, of which arachidonic acid (AA) is a major component. This provides a plausible biological mechanism whereby SNPs could impart less effective maturation of apoA-I, which could result in lower plasma HDL levels. Since HDL particles transport about 40% of the plasma phospholipids, and since RBC membrane phospholipids exchange with lipoprotein phospholipids (which carry AA), it is conceivable that SNPs in PCOLCE2 could impact RBC membrane AA composition [38]. HDL levels themselves are strongly and repeatedly related to cardiovascular disease outcomes [39,40] and this observation could reveal underlying mechanisms, though recent evidence suggests all genetically-determined differences in HDL levels are not consistently associated with differences in cardiovascular disease risk and, further, that using HDL cholesterol as a target for therapy (i.e., intervening to raise low levels) is ineffective at reducing risk for cardiovascular disease risk [41].

4.3 ELOVL2

Previous studies have identified SNPs in both ELOVL2 and the nearby gene SYCP2L as being significantly related to fatty acid proportions in plasma phospholipids. In particular, Lemaitre et al. [12] identified 2 SNPs in SYCP2L (rs6918936 with EPA levels and rs4713103 with DPA and DHA levels). Both SNPs were identified as significant in our analysis, though only showing significant association with DPA; DHA only attained sub-threshold significance (both with p=2×10−6), and EPA even less (p>0.001) (details not shown). Additional SNPs within ELOVL2 have also been associated with plasma phospholipid fatty acid patterns, metabolite levels and other metabolic traits [12,13,42,43]. Many of these SNPs are replicated in our analysis (details not shown).

ELOVL2 on chromosome 5 encodes a long chain fatty acid elongase. The elongase is one of seven ELOVL-family proteins that act primarily on polyunsaturated fatty acids [44] and ELOVL2 is critical in the elongation of DPA n-3 to DHA [45] (see also Supplemental Figure 2). The strong direct associations between DPA n-3 levels and SNPs in this gene provide further evidence of this relationship. In the transformation of DPA-n3 to DHA, elongation to tetracosapentaenoic acid (TPA; more commonly 24:5n3) by ELOVL2 is a key step, and SNPs contributing to reduced efficiency in this process would be expected to produce more DPAn3, less TPA, and less DHA as the end product. On the other hand, a functional mutation in ELOVL2 could also slow the synthesis of DPA n-3 from EPA. Although it is difficult to predict how these two counterbalancing processes might affect DPA n-3 membrane content, our finding of a direct relation between DPA n-3 and SNPs in ELOVL2 suggest, as have Gregory et al.[45], that conversion to TPA may be the more rate-limiting step. We did not measure TPA, but it is worth noting that while DHA did not achieve our threshold of significance, it was negatively associated with the presence of many SNPs (1×10−5<p<5×10−7; details not shown). This evidence combined with evidence from previous GWAS studies suggests that genetic variability may influence the levels of long-chain polyunsaturated omega-3 fatty acids.

4.4 FADS

Our analysis identified many strong association signals on chromosome 11, all in or near the FADS gene region which is well-documented to be associated with fatty acid proportions [12,13]. The FADS genes (FADS1, FADS2 and FADS3) are fatty acid desaturase genes. The proteins encoded by these genes are key enzymes involved in the the desaturation of n-3 and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids as follows: FADS1 desaturates at the delta-5 position [e.g., the conversion of DGLA (20:3n6) to AA (20:4n6)] and FADS2 desaturates at the delta-6 position [e.g., the conversion of LA (18:2n6) to GLA (18:3n6)] [22,46]. FADS3 has non-specific, or currently ill-defined desaturation activity (see also Supplemental Figure 2). Recent work has identified two major haplotypes spanning FADS1 and FADS2. Our analyses support the presence of these haplotypes in this sample, as well as the finding that the more common haplotype is associated with increased efficiency of long-chain fatty acid synthesis [47]. Furthermore, these genes have been shown to be associated with a number of phenotypes in SNP association studies, including certain plasma fatty acids [48,49], plasma lipoproteins [48,50], and response to lipid therapy [51] as well as DNA methylation levels [52].

A nearby gene in which SNP associations were found (DAGLA) encodes diacylglycerol lipases alpha. Two of the SNPs (rs1692120 (upstream) and rs198426 (within DAGLA)) found to be significantly associated in our analysis have been shown in prior research to have significant associations with DPA and ALA [12]. The lipase is a key enzyme in endocannabinoid synthesis pathways [53] and has been previously identified as associated with plasma phospholipid n-3 fatty acids in the CHARGE consortium [12]. Endocannabinoids modify risk-related patterns including having an effect on eating behavior. An association of diacylglycerol lipase SNPs with the RBC membrane fatty acid composition is not necessarily intuitive, nor is it immediately apparent why association are with increasing DGLA levels. It is also not apparent that the association is because of endogenous RBC-DAGLA activity [54] or is a secondary consequence of its activity in other tissues.

4.5 LPCAT3 (alt. MBOAT5)

Little to no evidence exists in the GWAS literature connecting this region of chromosome 12 with fatty acid and other phenotypes. LPCAT3 encodes lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3, yielding a protein which mediates the transfer of fatty acids between glycerol-lipids. LPCAT3 favors the transfer of saturated, as opposed to unsaturated, fatty acids [55]. While other LPAT genes have been identified in GWAS studies on lipid endpoints or, shown to be associated with cardiovascular risk [48,56], LPCAT3 is a novel observation with SNPs explaining a modest amount of variation in LA and OA. The sn2 position of phospholipids primarily carries polyunsaturated fatty acids, and limitation of LPCAT3 activity increases the abundance of polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as linoleic acid, over monounsaturated fatty acids such as oleic acid as observed here. Given the general interest in altering the relative abundances of these two fatty acid classes this association could provide valuable insight to underlying biology.

The only published reports correlating RBC fatty acid composition to endpoints in the Framingham Offspring Cohort focused on the long-chain omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA or trans fatty acids [4,7]. It is important to note that none of the SNP – fatty acid relations observed in this current analysis found significant associations for any of these fatty acids. This is perhaps because RBC levels of these fatty acids are more strongly determined by variations in dietary intake than are any other fatty acids [57,58]. However, other explanations are also possible (see following paragraph for some details). We previously reported that “heritability” explained much of the variability in RBC EPA+DHA (the Omega-3 Index) in this cohort [4]. When estimates of EPA+DHA intake (from food and supplements) were added to the model, the proportion of variability assigned to heritability diminished from 50% to 32%, suggesting that commonalities in eating patterns among families accounted for a large portion of heritability. In the present analysis, dietary fatty acid intake was not taken into account (since fatty acid intake data were not available for 1/4 of the cohort), and thus our ability to detect genetic influences was likely diminished due to unaccounted effects of diet on RBC fatty acid patterns. Other efforts have suggested 40–70% of variation in fatty acids is accounted for by genetic variation [9]. However, multiple types of genetic information from very large cohorts may be needed to reveal genetic vs. non-genetic influences in phenotypes [59].

4.6 Limitations

While this analysis has yielded a mix of biologically plausible novel genetic loci, as well as replicating prior genome-wide associations, there are a few limitations worth noting. The first was the lack of dietary data (especially relevant for EPA and DHA) described above, with the related issue that proportions of multiple RBC fatty acids can be highly inter-correlated [4]. Further work is necessary to develop fatty acid-specific models that leverage dietary covariates, that explicitly model the complex correlation structure between fatty acids, and that consider ratios of fatty acids as opposed to single fatty acids. Second, our analysis only considers common variants. Exome sequencing of the Framingham Offspring cohort is ongoing, and future analyses should consider the potential role of rare genetic variation in explaining fatty acid levels. Third, the family structure of the Framingham data meant that the effective sample size for our analysis was lower than the actual sample size of 2,633, limiting power to identify associated SNPs. Fourth, as is the case with any genome-wide association study, use of conservative significance levels, as we have done here, provides protection against false positives, but can lead to reduced ability (low power) to identify additional phenotype-genotype associations. Alternative methods (e.g., candidate gene/pathway analyses that build more biologically-informed statistical models), combining this sample with others, or gathering additional larger samples will be needed to further characterize potential gene-fatty acid relationships. These further analyses should also consider the potential role that rare (MAF<1%) genetic variation may play in fatty acid metabolism. Finally, replication of the novel loci identified in this paper should be sought after in independent samples, along with consideration of impact of causal loci on gene expression and associations with DNA methylation.

4.7 Conclusions

In seeking SNP relations for fourteen red blood fatty acid levels, we identified three novel loci, and replicated two others. Further work is needed to fine map the new regions of genetic interest (PCOLCE2, LPCAT3 and TRIM58) in independent samples, and analyze data using more biologically-informed models to potentially establish causal relationships between genetic variation and fatty acid metabolism.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We analyzed over 2.5 million SNPs for association with 14 RBC fatty acids, one of the largest GWAS studies of RBC fatty acids to date

We identified novel associations with PCOLCE2 and LPCAT3

We replicated previous strong associations with FADS and ELOVL

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute (R15HG006915; NT). This study was supported in part by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI; R01 HL089590) and by Contract N01-HC-25195, the Framingham Heart Study (NHLBI) and Boston University School of Medicine.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pottala JV, Garg S, Cohen BE, Whooley Ma, Harris WS. Blood eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids predict all-cause mortality in patients with stable coronary heart disease: the Heart and Soul study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:406–12. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.896159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shearer GC, Pottala JV, Spertus Ja, Harris WS. Red blood cell fatty acid patterns and acute coronary syndrome. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5444. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Block R, Harris W, Reid K, Spertus J. Omega-6 and trans fatty acids in blood cell membranes: a risk factor for acute coronary syndromes? Am Heart J. 2008;156:1117–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.07.014.Omega-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris WS, Pottala JV, Lacey SM, Vasan RS, Larson MG, Robins SJ. Clinical correlaes and heritability of erythrocyte eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid content in the Framingham Heart Study. Atherosclerosis. 2012;225:425–431. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.05.030.Clinical. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farzaneh-Far R, Harris W, Garg S, Na B, Whooley MA. Inverse association of erythrocyte n-3 fatty acid levels with inflammatory biomarkers in patients with stable coronary artery disease: The Heart and Soul Study. Atherosclerosis. 2009;205:538–543. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.12.013.Inverse. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston D, Deuster P, Harris W, Macrae H, Dretsch M. Red blood cell omega-3 fatty acid levels and neurocognitive performance in deployed U.S. Servicemembers. Nutr Neurosci. 2013;16:30–38. doi: 10.1179/1476830512Y.0000000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan Z, Harris W, Beiser A, Au R, Himali J, Debette S, et al. Red blood cell omega-3 fatty acid levels and markers of accelerated brain aging. Neurology. 2012;78:658–664. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318249f6a9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pottala JV, Yaffe K, Robinson J, Espeland M, Wallace R, Harris WS. Higher RBC EPA+DHA corresponds with larger total brain and hippocampal volumes: WHIMS-MRI study. Neurology. 2014 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemaitre RN, Siscovick DS, Berry EM, Kark JD, Friedlander Y. Familial aggregation of red blood cell membrane fatty acid composition: the Kibbutzim Family Study. Metabolism. 2008;57:662–668. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shearer GC, Harris WS, Pedersen TL, Newman JW. Detection of omega-3 oxylipins in human plasma and response to treatment with omega-3 acid ethyl esters. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:2074–81. doi: 10.1194/M900193-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jump DB. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid regulation of hepatic gene transcription. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2008;19:242–247. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3282ffaf6a.N-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemaitre RN, Tanaka T, Tang W, Manichaikul A, Foy M, Kabagambe EK, et al. Genetic loci associated with plasma phospholipid n-3 fatty acids: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies from the CHARGE Consortium. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suhre K, Shin SY, Petersen AK, Mohney RP, Meredith D, Wägele B, et al. Human metabolic individuality in biomedical and pharmaceutical research. Nature. 2011;477:54–60. doi: 10.1038/nature10354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.TT, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. 2010. pp. 707–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gieger C, Geistlinger L, Altmaier E, Hrabé de Angelis M, Kronenberg F, Meitinger T, et al. Genetics meets metabolomics: a genome-wide association study of metabolite profiles in human serum. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000282. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris WS, Varvel S, Pottala J, Warnick G, McConnell J. The comparative effects of an acute dose of fish oil on omega-3 fatty acid levels in red blood cells versus plasma: implications for clinical utility. J Clin Lipidol. 2013;7:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun Q, Ma J, Campos H, Hankinson SE, Hu FB. Comparison between plasma and erythrocyte fatty acid content as biomarkers of fatty acid intake in US women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:74–81. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.1.74. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17616765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Psaty BM, O’Donnell CJ, Gudnason V, Lunetta KL, Folsom AR, Rotter JI, et al. Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology (CHARGE) Consortium: Design of prospective meta-analyses of genome-wide association studies from 5 cohorts. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2:73–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.829747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Govindaraju DR, Cupples LA, Kannel WB, O’Donnell CJ, Atwood LD, D’Agostino RB, et al. Genetics of the Framingham Heart Study Population. Adv Genet. 2008;62:33–65. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(08)00602-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cupples LA, Arruda HT, Benjamin EJ, D’Agostino RB, Demissie S, DeStefano AL, et al. The Framingham Heart Study 100K SNP genome-wide association study resource: overview of 17 phenotype working group reports. BMC Med Genet. 2007;8(Suppl 1):S1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marques-Lopes I, Ansorena D, Astiasarann I, Forga L, Martinez J. Postprandial de novo lipogenesis and metabolic changes induced by a high-carbohydrate, low-fat meal in lean and overweight men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:253–61. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee H, Park W. Unsaturated fatty acids, desaturases, and human health. J Med Food. 2014;17:189–97. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2013.2917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frazer Ka, Ballinger DG, Cox DR, Hinds Da, Stuve LL, Gibbs Ra, et al. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449:851–61. doi: 10.1038/nature06258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y, Willer CJ, Ding J, Scheet P, Abecasis GR. MaCH: using sequence and genotype data to estimate haplotypes and unobserved genotypes. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:816–34. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.R n.d [Google Scholar]

- 26.GenAbel. n.d http://www.genabel.org/tutorials/ABEL-tutorial#tth_sEc5.2.

- 27.Gieger C, Radhakrishnan A, Cvejic A, Tang W. New gene functions in megakaryopoiesis and platelet formation. Nature. 2011;480:201–208. doi: 10.1038/nature10659.New. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van der Harst P, Zhang W, Leach I. Seventy-five genetic loci influencing the human red blood cell. Nature. 2012;492:369–375. doi: 10.1038/nature11677.Seventy-five. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamatani Y, Matsuda K, Okada Y, Kubo M, Hosono N, Daigo Y, et al. Genome-wide association study of hematological and biochemical traits in a Japanese population. Nat Genet. 2010;42:210–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park Y, Harris W. EPA, not DHA, decreases mean platelet volume in normal subjects. Lipids. 2002;37:941–946. doi: 10.1007/s11745-006-0984-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goodnight S, Harris W, Connor W. The effects of dietary omega-3 fatty acids on platelet composition and function in man: a prospective, controlled study. Blood. 1981;58:880–885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knapp H. Dietary fatty acids in human thrombosis and hemostasis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:1687S–1698S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.5.1687S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park Y, Harris W. Journal of medicinal food. J Med Food. 2009;12:809–813. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2008.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larson MG, Ashmore J, Harris K, Vogelaar J, Pottala JV, Sprehe M, et al. Effects of omega-3 acid ethyl esters and aspirin, alone and in combination, on platelet function in healthy subject. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100:634–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steiglitz BM, Keene DR, Greenspan DS. PCOLCE2 encodes a functional procollagen C-proteinase enhancer (PCPE2) that is a collagen-binding protein differing in distribution of expression and post-translational modification from the previously described PCPE1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49820–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209891200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu J, Gardner J, Pullinger CR, Kane JP, Thompson JF, Francone OL. Regulation of apoAI processing by procollagen C-proteinase enhancer-2 and bone morphogenetic protein-1. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:1330–9. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M900034-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Francone OL, Ishida BY, de la Llera-Moya M, Royer L, Happe C, Zhu J, et al. Disruption of the murine procollagen C-proteinase enhancer 2 gene causes accumulation of pro-apoA-I and increased HDL levels. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:1974–83. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M016527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reed C. Phospholipid exchange between plasma and erythrocytes in man and the dog. J Clin Investig. 1968;47:749–760. doi: 10.1172/JCI105770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Assmann G, Cullen P, Schulte H. The Munster Heart Study (PROCAM). Results of follow-up at 8 years. Eur Heart J. 19998;19:A2–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson PW, Abbott RD, Castelli WP. High density lipoprotein cholesterol and mortality. The Framingham Heart Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1988;8:737–741. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.8.6.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Voight BF, Peloso GM, Orho-Melander M, Frikke-Schmidt R, Barbalic M, Jensen MK, et al. Plasma HDL cholesterol and risk of myocardial infarction: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet. 2012;380:572–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60312-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inouye M, Ripatti S, Kettunen J, Lyytikäinen LP, Oksala N, Laurila PP, et al. Novel Loci for metabolic networks and multi-tissue expression studies reveal genes for atherosclerosis. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Demirkan A, van Duijn CM, Ugocsai P, Isaacs A, Pramstaller PP, Liebisch G, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies novel loci associated with circulating phospho- and sphingolipid concentrations. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tamura K, Makino A, Hullin-Matsuda F, Kobayashi T, Furihata M, Chung S, et al. Novel lipogenic enzyme ELOVL7 is involved in prostate cancer growth through saturated long-chain fatty acid metabolism. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8133–40. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gregory MK, Gibson Ra, Cook-Johnson RJ, Cleland LG, James MJ. Elongase reactions as control points in long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid synthesis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29662. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Catala A. Five decades with polyunsaturated fatty acids: chemical synthesis, enzymatic formation, lipid peroxidation and its biological effects. J Lipds. 2013:710290. doi: 10.1155/2013/710290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ameur A, Enroth S, Johansson A, Zaboli G, Igl W, Johansson ACV, et al. Genetic adaptation of fatty-acid metabolism: a human-specific haplotype increasing the biosynthesis of long-chain omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:809–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu JHY, Lemaitre RN, Manichaikul A, Guan W, Tanaka T, Foy M, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies novel loci associated with concentrations of four plasma phospholipid fatty acids in the de novo lipogenesis pathway: results from the Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology (CHARGE) consortiu. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2013;6:171–83. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.112.964619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanaka T, Shen J, Abecasis GR, Kisialiou A, Ordovas JM, Guralnik JM, et al. Genome-wide association study of plasma polyunsaturated fatty acids in the InCHIANTI Study. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakayama K, Bayasgalan T, Tazoe F, Yanagisawa Y, Gotoh T, Yamanaka K, et al. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the FADS1/FADS2 gene is associated with plasma lipid profiles in two genetically similar Asian ethnic groups with distinctive differences in lifestyle. Hum Genet. 2010;127:685–690. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0815-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barber MJ, Mangravite LM, Hyde CL, Chasman DI, Smith JD, McCarty Ca, et al. Genome-wide association of lipid-lowering response to statins in combined study populations. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Howard TD, Mathias Ra, Seeds MC, Herrington DM, Hixson JE, Shimmin LC, et al. DNA methylation in an enhancer region of the FADS cluster is associated with FADS activity in human liver. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bisogno T, Howell F, Williams G, Minassi A, Cascio MG, Ligresti A, et al. Cloning of the first sn1-DAG lipases points to the spatial and temporal regulation of endocannabinoid signaling in the brain. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:463–8. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mizuno M, Sugiura Y, Okuyama H. acylglycerophosphate acyltransferase and lipases in porcine erythrocyte membranes. 1984;25:843–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jain S, Zhang X, Khandelwal PJ, Saunders AJ, Cummings BS, Oelkers P. Characterization of human lysophospholipid acyltransferase 3. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:1563–70. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800398-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shiffman D, Trompet S, Louie JZ, Rowland CM, Catanese JJ, Iakoubova Oa, et al. Genome-wide study of gene variants associated with differential cardiovascular event reduction by pravastatin therapy. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arab L. Biomarkers of Nutritional Exposure and Nutritional Status Biomarkers of Fat and Fatty Acid Intake. 2003;1:925–932. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hodson L, Skeaff C, Fielding B. Fatty acid composition of adipose tissue and blood in humans and its use as a biomarker of dietary intake. Prog Lipid Res. 2008;47:348–80. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Agarwala V, Flannick J, Sunyaev S, Altshuler D. Evaluating empirical bounds on complex disease genetic architecture. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1418–27. doi: 10.1038/ng.2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.