Abstract

Background

Molecular dynamics simulations can complement experimental measures of structure and dynamics of biomolecules. The quality of such simulations can be tested by comparisons to models refined against experimental crystallographic data.

Methods

We report simulations of a DNA and RNA duplex in their crystalline environment. The calculations mimic the conditions for PDB entries 1D23 [d(CGATCGATCG)2] and 1RNA [(UUAUAUAUAUAUAA)2], and contain 8 unit cells, each with 4 copies of the Watson-Crick duplex; this yields in aggregate 64 µs of duplex sampling for DNA and 16 µs for RNA.

Results

The duplex structures conform much more closely to the average structure seen in the crystal than do structures extracted from a solution simulation with the same force field. Sequence-dependent variations in helical parameters, and in groove widths, are largely maintained in the crystal structure, but are smoothed out in solution. However, the integrity of the crystal lattice is slowly degraded in both simulations, with the result that the interfaces between chains become heterogeneous. This problem is more severe for the DNA crystal, which has fewer inter-chain hydrogen bond contacts than does the RNA crystal.

Conclusions

Crystal simulations using current force fields reproduce many features of observed crystal structures, but suffer from a gradual degradation of the integrity of the crystal lattice.

General significance

The results offer insights into force-field simulations that tests their ability to preserve weak interactions between chains, which will be of importance also in non-crystalline applications that involve binding and recognition.

1 Introduction

RNA and DNA molecules play an important role in many biological processes, and an understanding of their structure and dynamics is indispensable for a complete understanding of their function. Molecular dynamics simulations can offer a detailed complement to experiment, and nucleic acid simulations in a crystal environment have long been used to test simulations methods.[1, 2] A “modern” era began in the mid 1990’s with the introduction of Ewald-based methods to simulate long-range electrostatic interactions.[3] At about that time, simulations of Watson-Crick paired duplexes in both solution and the crystal lattice provided evidence that simulations remained stable for a few nanoseconds without the need for artificial restraints,[4–7] and that, not surprisingly, the duplex structure in the crystal lattice environment more closely resembles the experimental crystal structures than do simulations in a solution environment. Subsequent studies in a crystalline lattice employed longer time scales and different force fields, reaching broadly similar conclusions.[8–13]. Advances in computing speed have spurred a new round of biomolecular crystal simulations (mostly for proteins[14–21]), that use larger simulation cells and pay increased attention to the properties of the crystal lattice, as well as to the structural characteristics of individual chains.

Here we report results of molecular dynamics simulations of duplexes of DNA (PDB ID: 1D23 [22]) and RNA (PDB ID: 1RNA [23, 24]) for 2.0 and 0.5 µs; both crystals are in the P212121 space group, with four duplexes per unit cell. The periodic unit in the simulations is a “supercell” containing 8 unit cells, so the simulations contain 32 copies of each duplex. Parallel simulations of a single duplex in water (neutralized by Na+ counterions) are reported for comparison to the crystal simulations. Since a large number of solution simulations of DNA and RNA helices have previously been reported,[3, 25–32] our primary emphasis here is on the properties of the crystal lattice, and the ability of current simulation methods to reproduce such behavior. The simulation results explore the details of stability of the duplexes and crystal packing effects in µs dynamics; this time scale has been explored in earlier solution simulations of DNA duplexes.[30, 31]

The main results of this paper are as follows: first, the average duplex structure from the crystal simulation more closely resembles the experimental crystal structure than the average structure in a solution simulation. Some details of the crystal structure, such as groove widths, are averaged out in solution simulations but not in the crystal, whereas other sequence-dependent variations are maintained. These latter include the characteristic alternating pattern of base pair roll/twist in alternating A-U sequences in RNA and the BI/BII pattern in the backbone torsion angles (ε-ξ) in DNA.[33–35] As in previous simulations, the backbone conformation presents more of a challenge to simulations than does base positioning. However, for both DNA and RNA, the integrity of the crystal lattice is slowly degraded, and a full equilibration is not achieved. The interchain contacts that hold these lattices together are less extensive than is typical for protein crystals, and are likely to be influenced by ions in ways that are poorly represented here. A partial “melting” of the crystal lattice takes place at seemingly random points in the supercell, such that the 32 equivalent interfaces become rather heterogenous, with some quite close to their original (experimental) configurations, and others are displaced in ways that are irreversible on the time scales sampled here.

2 Models and computational methods

Coordinates for the initial state of the RNA and DNA came from PDB entries:1RNA and 1D23. Crystal structures of the RNA and DNA crystal were constructed according to space group P212121, where four symmetry-related copies of the duplex make up one unit cell. We constructed a supercell of 2 × 2 × 2 unit cells by using the PropPDB module of the Amber12 package,[36] yielding an orthogonal box of size 68.22 × 89.22 × 98.22 Å for 1RNA, and 77.86 × 79.26 × 66.60 Å for 1D23. Views of the supercells along the three crystal vectors are shown in Fig. 1. For the DNA crystal simulation, Mg2+ ions were used as counterions: there are two Mg(H2O)62+ complexes per asymmetric unit in the 1D23 crystal structure, and 7 additional Mg(H2O)62+ ions per duplex were added to neutralize the 18 phosphate groups. The RNA supercell system was neutralized with 26 Na+ ions per duplex. All counterions and water molecules were added to the super cell using the AddToBox program in Amber. The DNA system for the solution simulation contained one DNA duplex and 5045 water molecules together with 18 Na+ ions in a truncated octahedral box with periodic boundary conditions; the RNA simulation had 7694 waters and 26 Na+ ions. Further simulation deatils are given in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Two three dimension views of the RNA (left) and DNA (right) packing in supercells. The supercell contains 8 unit cells in a 2 × 2 × 2 arrangement; each unit cell comprises four RNA/DNA molecules. The cyan box is unit cell.

Table 1.

Details of the simulations. Simulation speed is measured on a single NVIDIA GTX780 card for the RNA simulations, and on a Quadro K5000 card for the DNA simulations. Ions are Mg2+ for the DNA crystal and Na+ for the other simulations. Atom counts do not include the “extra points” in the TIP4P/Ew waters.

| DNA | RNA | DNA(soln) | RNA(soln) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| number of waters | 8578 | 12300 | 5045 | 7694 |

| number of ions | 288 | 832 | 18 | 26 |

| total number of atoms | 46246 | 65892 | 15785 | 23988 |

| mean internal pressure, atm. | 30 | 97 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| density, g/cm3 | 1.433 | 1.446 | 1.044 | 1.034 |

| simulation speed, ns/day | 16.7 | 21.5 | 24.3 | 26.9 |

| time analyzed, µs | 2.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.0 |

We carried out crystal simulations using the parm99 force field[37] with bsc0 modifications[38] for both duplexes, and added the chiOL3 modifications[39] for RNA. The water model used was TIP3P[40] for DNA and TIP4P/Ew[41] for RNA; monovalent ion parameters were taken from Ref. [42] and Mg2+ parameters from Ref. [43]. Simulations of nucleic acids in solution show only small conformational dependencies on the water model used. As an example, we compared our TIP4P/Ew simulation of 1RNA in solution with results from Ref.[25], where a TIP3P water model was used. Average values twist, roll, helical twist, propellor twist, slide, x-displacement and helical rise were essentially the same in the two simulations. We do not yet have similar comparisons for crystal simulations.

The minimization, equilibration, and production dynamics were performed using the pmemd module of Amber12.[36, 44, 45] The SHAKE algorithm was applied to all bonds involving hydrogen atoms. Force calculations were performed with periodic boundary conditions, a 9.0 Å cutoff on real space interactions, a homogeneity assumption for long-range Lennard-Jones contributions, and smooth particle-mesh Ewald electrostatics. An energy minimization procedure was used first to any bad contacts in the starting conformation. Next, the system was equilibrated at the experimental data collection temperatures of 308 K for RNA and 273 K for DNA, with successive restraints on the RNA/DNA atoms of 10.0, 1.0 and 0.1 kcal/(mol-Å2) for a total of 40 ns. The volume was kept fixed at the experimental value, and the system pressure monitored. The number of water molecules was adjusted by trial and error to obtain a simulation with an external pressure near 1 atm. Finally, unrestrained production dynamics were propagated at a 2 fs time step for 2.0 µs for DNA and 0.5 µs for RNA. A total of 4000 equally-spaced snapshots for DNA and 2500 for RNA were saved for subsequent analysis. Some details of the simulation are collected in Table 1. The solution simulations followed the general procedures of the “ABC” simulations,[27–29, 46] and placed a single duplex in a truncated octahedron, neutralized by Na+ ions, which were equilibrated in a similar fashion.

Results were analyzed using Amber cpptraj module, and figures were prepared by Chimera and VMD molecular visualization programs. Helical parameters throughout the trajectories were monitored with the Curves+ program.[47] The BI and BII configurations in DNA were characterized by the angles ε and ξ of the DNA backbone or by the angle difference (ε-ξ), which is −90° for BI and +90° for BII phosphates.[35] Interfaces were analyzed using the PISA program.[48]

3 Analysis of duplex structures and comparison with solution simulations

The root mean square deviations (rmsd) from the crystal structure for all heavy atoms (of all 32 duplexes) are shown in Fig. 2. For the curves labeled “best-fit”, an optimal translation and rotation to fit the crystal coordinates was determined for each duplex in each snapshot; these values reach an apparent plateau of about 1.2 Å in about 200 ns simulation. For the curves labeled “lattice”, the duplexes were superimposed on the crystal configuration using only the lattice symmetry parameters, with no fitting. (See Ref. [19] for a detailed explanation of these statistics.) These latter values reflect both deviations of individual duplexes from the crystal configuration and the degradation of the lattice itself. The latter continues for the entire trajectory, and will be analyzed in Section 4.

Figure 2.

Positional RMSDs of all heavy atoms for RNA and DNA relative to the initial X-ray structure in the course of simulation.

The best-fit and solution average structures are compared to the experimental crystal configuration in Fig. 3, and some statistics are given in Table 2. As expected, and as seen in earlier crystal simulations, the average structure in solution deviates much more from the crystal configuration than does the average structure from the crystal simulation. The crystal simulation deviations are larger in the backbone both for DNA and RNA than for the bases. Some details of these differences are provided in the following sections.

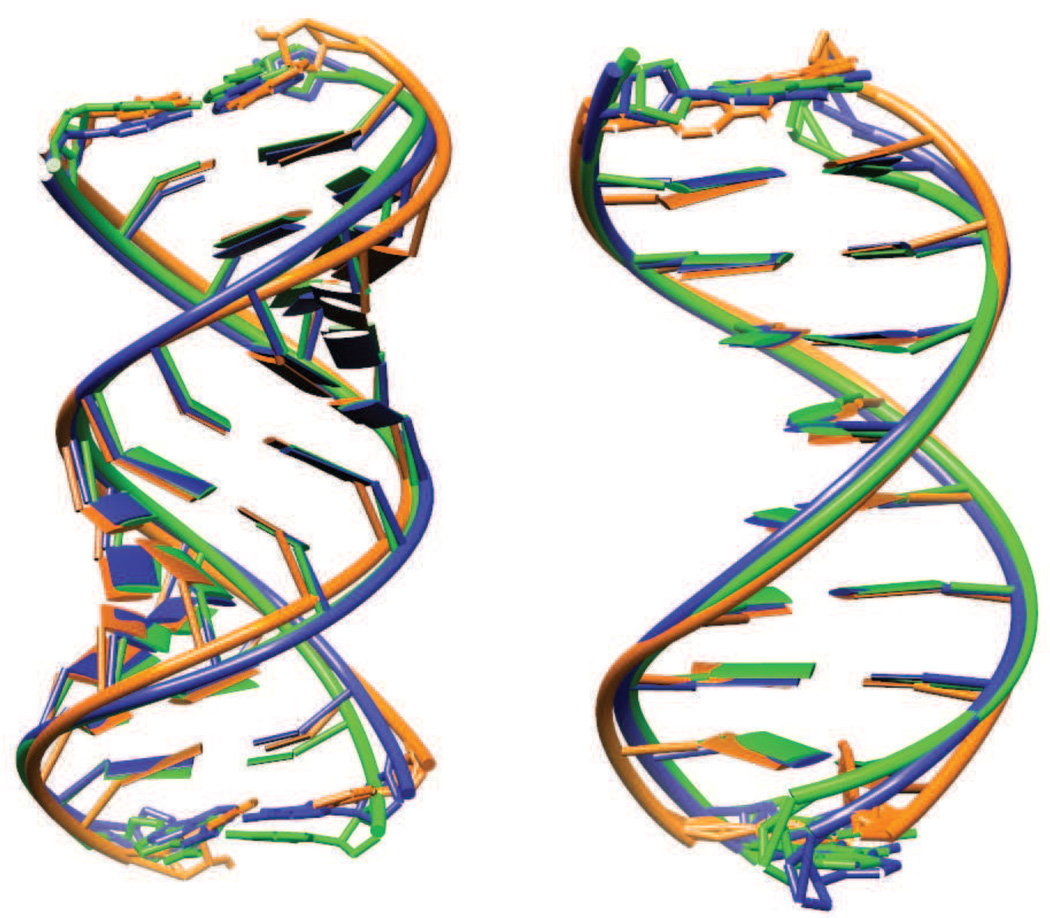

Figure 3.

Superpositions of the solution average structure (orange) and the best-fit average structure (blue) for RNA (left) and DNA (right) versus the deposited crystal structures (green).

Table 2.

Root mean square deviations (Å) from the deposited crystal structures for 1RNA and 1D23. The statistics in each box are heavy atoms, backbone atoms, base atoms RMSD of average structure against the crystal structure. The values in parentheses exclude the terminal residues.

| All heavy atoms | Backbone | Base | All heavy atoms (solution) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| best-fit (RNA) | 0.78 (0.71) | 0.87 | 0.59 | 1.38 (1.12) |

| lattice (RNA) | 0.93 | 1.04 | 0.74 | ~ |

| best-fit (DNA) | 0.77 (0.64) | 0.89 | 0.56 | 1.83 (1.34) |

| lattice (DNA) | 1.12 | 1.23 | 0.95 | ~ |

3.1 Groove widths

The A- and B-form helices for RNA and DNA have very different geometries, and can be monitored as groove “widths” and “depths”. In Fig. 4, we use a simple measure groove width, based on phosphate-phosphate distances from one chain to its complementary strand. For RNA, the sequence dependence of the widths of major groove is suppressed in solution, leading to a more regular pattern of distances than are seen in the crystal. Figs. 3 and 4 show that the major groove widens slightly compared with crystal structure. This behavior of solution simulations has been discussed earlier, in connection with attempts to characterize how NMR constraints determine the details of A-form helices in RNA.[49] Furthermore, fluctuations of the major groove in the crystal simulation are much smaller than those in the solution simulation.

Figure 4.

Plots of major-groove width for RNA and minor-groove width for DNA in crystal and solution simulations. Widths in Å are defined by the distance between the phosphate atoms shown at the top and bottom. Vertical bars give the standard deviations of the fluctuations seen in the simulations.

For DNA, the minor groove width is greatest at phosphates P7/P8, not only in crystal structure but also in the crystal and solution simulations. This is related to the presence of a BII phosphate conformation at positions P7 and P17 in the crystal structure. The larger minor groove widths at positions P10 and P20 in solution are related to the larger fluctuations in the terminal residues that are characteristic of solution simulations. In addition, the wide minor groove at P7 is consistent with the large positive roll deformation (Fig.7, below) which compresses the major groove and then widens the minor groove.[50] (Because of the way steps are numbered, a wide minor groove separation between P7 and P18 should be correlated with a positive roll angle at position P5).

Figure 7.

DNA base pair step parameters, translational parameters are in angstroms (Å) and rotational parameters are in degrees (°).

3.2 Backbone conformations

The backbone of the 1RNA structure contains two kinks (at A23/U24 and U10/A11,) which divide the whole duplex into three roughly equal regions. The kinks result from changes in the α and γ backbone torsions from their typical values near 280 and 70, respectively. Table 3 lists the average values in both simulations, showing a reversion in the simulation back to the canonical A–type values. This reversion suggests that crystal packing forces are not sufficient (at least for the simulation analyzed here) to retain the unusual crystal configuration.

Table 3.

Average α and γ angles (degrees) in crystal and solution simulations. The data in parentheses are standard deviations.

| α (cryst) | α (cryst. sim.ave) | α (solution. sim.ave) | γ (cryst) | γ (cryst. sim.ave) | γ (solution.sim.ave) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A11 | 155 | 279 (29.9) | 281 (15.1) | 178 | 73 (23.7) | 64 (12.6) |

| U24 | 210 | 282 (12.9) | 282 (12.4) | 127 | 64 (9.5) | 63 (9.4) |

The DNA backbone generally has two major sub-forms, BI and BII, that can be characterized by the ε and ξ backbone torsion angles.[34, 35, 51] The range of ε and ξ torsion angles for BI structure varies within 120°–210° and 235°–295°, respectively, while for BII these vary from 210° to 300° and from 150° to 210°, respectively. The difference (ε-ξ) is near +90° for BII and near –90° for BI. In the crystal configuration, P2, P7, P12, P17 have a BII conformation, and all others have a BI conformation. Fig. 5 shows the fraction of BII configuration in the crystal and solution simulations. Both P7 and P17 largely maintain a BII conformation, whereas P2 and P12 revert to a mixture of BI and BII configurations. The percentages of the BII configuration at P2, P7, P12 and P17 are much smaller in the solution simulation.

Figure 5.

Conformational substates (BII) probability in the crystal and solution simulation along the sequence: P2 to P10 are in strand 1, P12 to P20 are in strand 2. In the crystal configuration, P2, P7, P12, P17 have a BII conformation, and all others have a BI conformation.

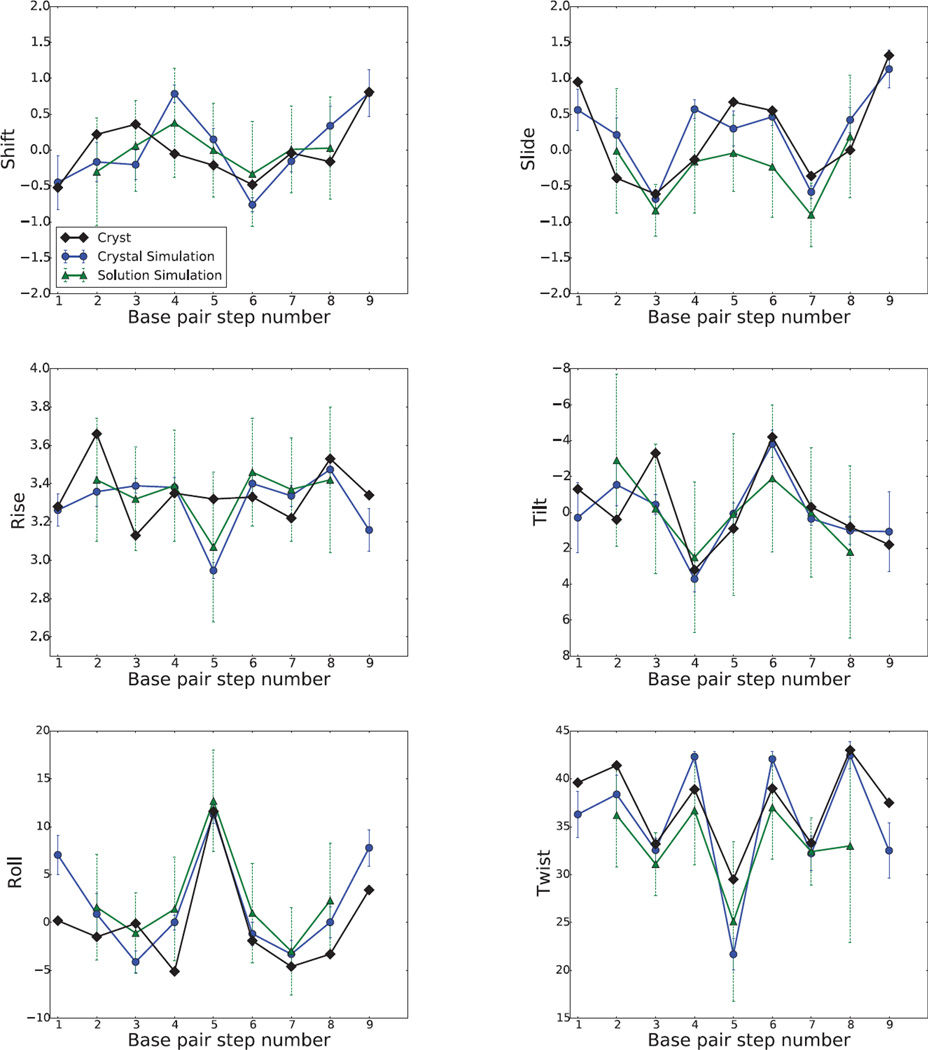

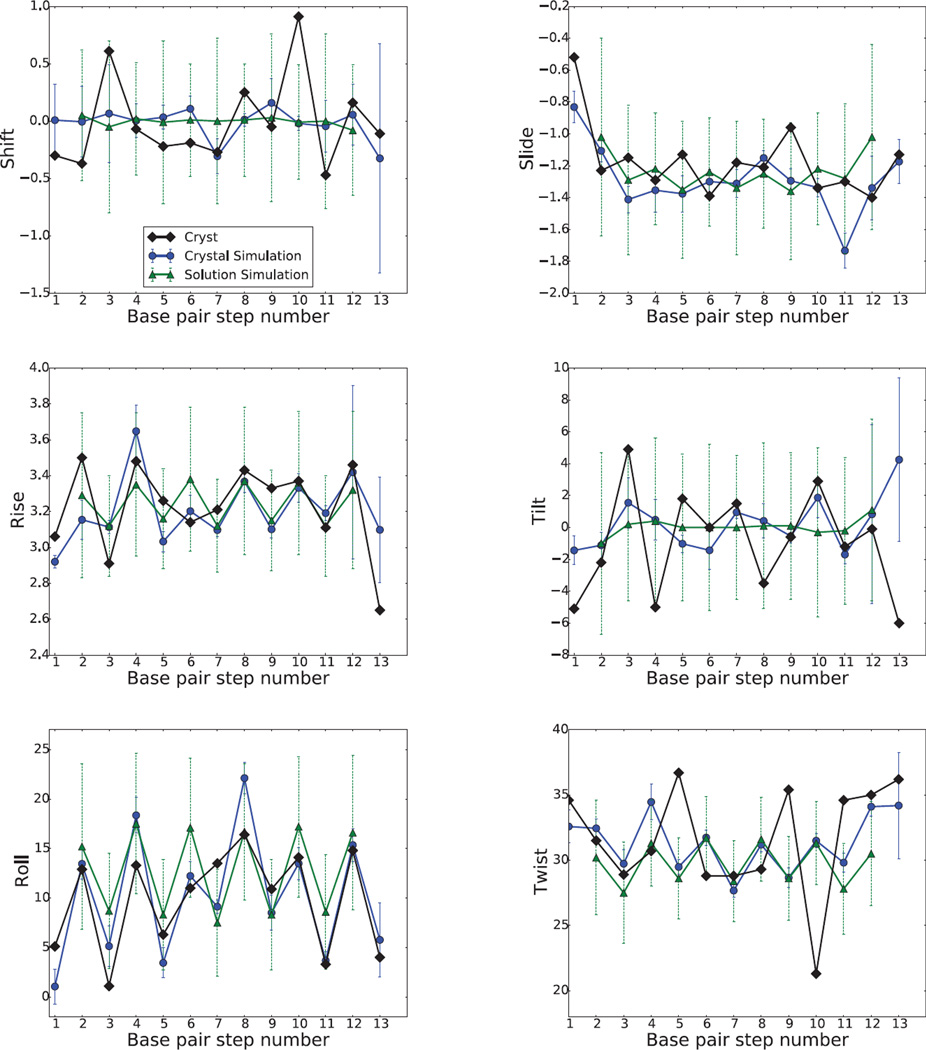

3.3 Base pair step parameters

Nucleic acid helices are commonly characterized by six helicoidal parameters (tilt, roll, twist, shift, slide, and rise) that describe the configuration of base steps[52]; simulation results are given in Figs. 6 and 7. There are a number of observations that can be made. First, the shift and tilt parameters are evened out in solution for RNA; this is much less true for DNA, and is less true for the other base-step parameters. Solution and crystal simulations are in close agreement for the rise, roll and helical twist parameters, especially for DNA. The fluctuations vary little between steps in the crystal simulation, except for the more flexible shift, rise, tilt and twist of the end base pair A13•U16/A14•U15 step. Second, fluctuations in base step parameters in solution (green dashed bars) are much greater than those in the crystal simulation (blue solid bars).

Figure 6.

RNA base pair step parameters, translational parameters are in angstroms (Å) and rotational parameters are in degrees (°).

The twist of nucleic acid helices is an “emergent” property of force fields, that is difficult to associate with particular interactions or backbone torsion angle preferences. The Amber potentials lead to slightly undertwisted helices in solution simulations.[32, 53] There are two unusual twist values (36.7 and 21.3) in RNA duplex at steps 5 and 10 shown in Fig.6, which is caused by two distinguished kinks dividing the whole duplex into three parts. However, in our simulation, these two unusual twist values in kink regions become 29.5 (28.7 in solution) for step 5 and 31.6 (31.5 in solution) for step 10 in average structures. Table 4 shows that the average twist is larger in the crystal simulation than in solution; it seems likely that the coaxial stacking interfaces (discussed below) serve to prevent the relaxation to an undertwisted state that is typically seen in solution simulations with this force field.[3, 25–29, 32] Some steps in solution simulations show evidence of bimodal distributions in the twist;[54] no such behavior is seen in the DNA simulations reported here. This may be due to sequence or crystal-packing effects, and further analysis of these points will be a subject of future study.

Table 4.

The average twist (in degrees) for the RNA and DNA average structures. Twist values were calculated using the program CURVES+, the average values including all residues.

| RNA | DNA | |

|---|---|---|

| exp. crystal | 31.7 | 37.3 |

| sim. crystal | 31.4 | 35.7 |

| sim. solution | 29.8 | 32.3 |

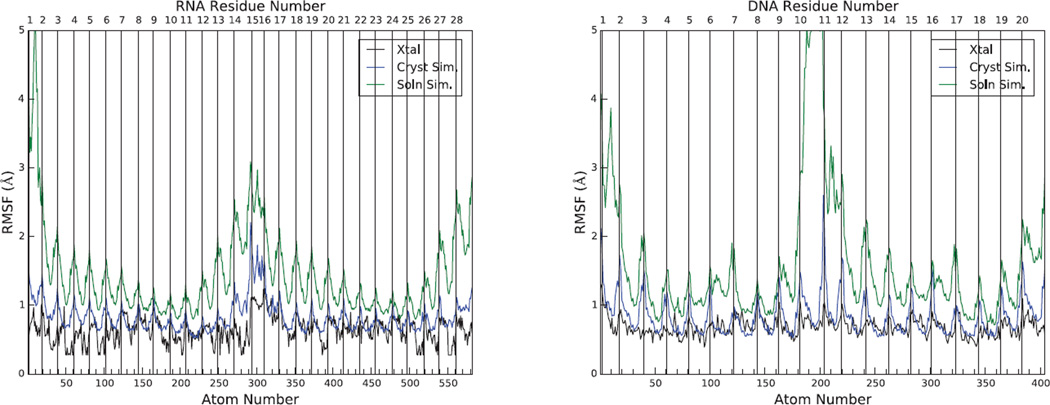

3.4 Fluctuations about the average structure

Simulated B-factors can be calculated from an MD trajectory using equation (1) and compared to crystallographic B-factors:

| (1) |

where μ is the root mean square fluctuation about a mean position. In Fig. 8, the simulated and experimental B-factors for RNA and DNA are reported. For both solution and crystal simulations, the fluctuations are calculated by superimposing each duplex onto the crystal conformation using an optimal rotation and translation movement. The phosphate groups show the highest deviations from the average structure, and the low points between these peaks represent base atoms.

Figure 8.

Root-mean-square fluctuations as function of heavy atom number for RNA (left) and DNA (right). The left half of each figure represents chain A, and the right half, chain B. Light vertical lines identify the phosphate atoms (excluding residues U1A15 for RNA and C1C11 for DNA). B-factors in 1RNA/1D23 (PDB entry) were converted to fluctuations using Eq. 1.

As expected, the fluctuations in solution (green curves) are higher than those in the crystal simulation (blue curves), especially at the chain termini (where large fluctuations and fraying take place in solution), but also in the centers of the duplexes. For RNA, the fluctuations in the crystal simulation are close to experiment except near the chain termini. This is also the case for the base atoms in the DNA (i.e. at the low points between peaks in Fig. 8), but the sugar-phosphate backbone atoms have larger fluctuations in the simulation. Note that the fluctuations reported here do not include the effects of the lattice distortion, which is fairly large for both RNA and DNA, as shown in Figs. 2 and 15; inclusion of these effects would result in fluctuations that are much larger than those shown in Fig. 8 (data not shown).

Figure 15.

The center of mass position for each of the 32 duplexes, where the origin represents their position in an ideal lattice.

4 Contacts and packing interactions

One of the features that distinguishes the present simulations from earlier ones is the size of the supercell used, and the length of the simulations. We have 32 copies of each RNA or DNA duplex, and hence 32 copies of each of the interactions between duplexes. This allows us to analyze the nature of these interactions, and the ability of current force fields and simulation protocols to correctly describe the behavior of these relatively weak interactions.

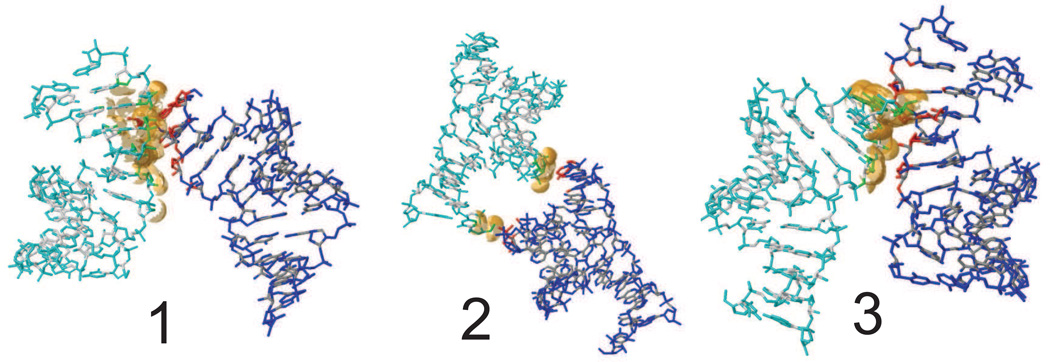

4.1 Crystal interfaces for RNA

In a crystal, each nucleic acid molecule makes several contacts with its neighboring molecules. Generally, the size of the pairwise interface between two neighboring molecules can be characterized by the number of contacts or the buried interface area. PDBe PISA (Proteins, Interfaces, Structures and Assemblies) shows three interfaces with nearest neighbors for RNA, shown in Fig. 9 and Table 5. Two interfaces (1 and 2 in Fig. 9) involve of the minor grooves of the symmetry related helices face each other at their ends; hydrogen bonds stabilized both contacts. The third interface places the major grooves of two duplexes face to face with each other. A few van der Waals contacts and CH–O hydrogen bonds (among residues U1, U22 and A9, U10, U15) stabilize this interface. The total surface area buried by the three listed interfaces is 1516 Å2 (twice the total of surface area of the three interfaces listed in Table 5), since in the crystal each duplex participates in two independent copies of each interface, e.g. one on the “left” and one on the “right”). The total surface area for an isolated duplex is 5134 Å2, so that 29% of the surface area is buried, and 71% is accessible to water and ions. This buried interface area is smaller than for many proteins: for example, the triclinic form of hen lysozyme (PDB code 4LZT) has 3030 Å2 (or 46%) of its surface area in contact with other proteins. The relatively small contact area for RNA (and for DNA, as discussed below) may increase the likelihood that the contacts may degrade during an imperfect simulation.

Figure 9.

Lattice contacts, showing the orientation of one RNA asymmetric unit relative to its neighbors. The contacts are shown as defined by PISA (Proteins, Interfaces, Structures and Assemblies; http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/pisa/).

Table 5.

Hydrogen bonds, van der Waals contacts and interactions between symmetry-related duplexes in RNA. The data in parentheses are standard deviations. Interface areas were computed by PISA (Proteins, Interfaces, Structures and Assemblies; http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/pisa/).

| Type | Interactions | Area(Å2) | Atom 1 | Symmetry operator |

Atom 2 | Xtal. dist. | Cryst. Sim. dist. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | minor groove –minor groove |

311.5 | O2/U1 | −x+1, y−1/2, −z+1/2 |

O2’/A11 | 3.01 | 2.78 (0.20) |

| O2’/A28 | O2/U18 | 3.02 | 2.80 (0.19) | ||||

| O3’/A28 | O2’/U18 | 3.00 | 3.10 (0.23) | ||||

| O2’/U1 | OP1/U12 | 3.30 | 4.28 (0.55) | ||||

| O2’/U2 | O2’/U10 | 2.46 | 4.02 (0.80) | ||||

| O2’/A3 | O2’/U20 | 3.20 | 3.86 (0.86) | ||||

| 2 | minor groove –minor groove |

304.3 | O2/U15 | x−1/2, −y+1/2, −z |

O2’/A25 | 2.67 | 3.31 (0.96) |

| O2’/A14 | O2/U4 | 2.77 | 2.99 (0.39) | ||||

| O3’/A14 | O2’/U4 | 3.01 | 3.69 (1.36) | ||||

| 3 | major groove –major groove |

138.8 | C6/U15 | −x+1/2, −y+1, z−1/2 |

O2’/U22 | 3.17 | 4.44 (0.94) |

| C5/U15 | O3’/U22 | 2.80 | 3.75 (0.69) | ||||

| O3’/A9 | O5’/U1 | 3.53 | 4.10 (1.11) | ||||

| O3’/A9 | C5’/U1 | 3.30 | 4.26 (1.10) | ||||

| OP1/U10 | C5’/U1 | 3.32 | 4.19 (1.21) |

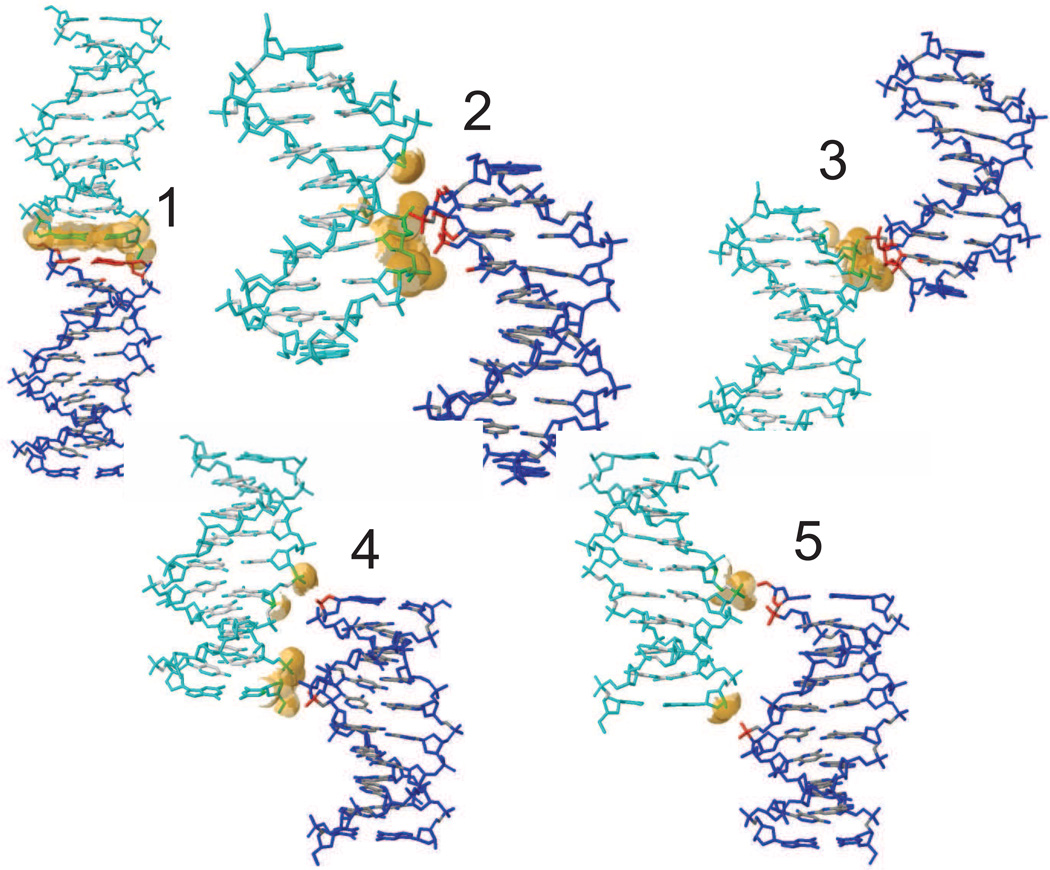

The first and second interfaces for RNA involve hydrogen bond interactions, whereas the third interface for RNA and all interfaces for DNA are characterized by less-specific van der Waals contacts. Most of the contact distances become larger in the simulation for both RNA and DNA; exceptions include most of the hydrogen bonds in RNA interfaces 1 and 2; the longer (and presumably weaker) CH–O interactions in RNA interface 3 are less-faithfully maintained; this interface also has a much smaller buried surface area in the crystal.

The averages shown in Table 5 hide a large amount of heterogeneity among the 32 copies of each interface present in the supercell. As an example, Fig. 10 shows the variation of two of the hydrogen bonds in interface 2 for each copy. It is clear that these interactions are well–maintained in about 22–24 copies, and completely broken in 8–10 copies. It is likely that longer simulations would result in more copies becoming distorted, leading to progressive distortion of the lattice, as is seen more clearly in the longer DNA simulation discussed below. The average distance of the molecular centers of mass of the duplexes interacting across interface 1 increases by 0.5 Å; across interface 3 the distance decreases by about the same amount; across interface 2 it stays almost the same as in the crystal (Fig. 11). Individual interfaces can deviate from the average by up to about 1 Å, indicative of significant heterogeneity.

Figure 10.

The average distances of O3’/A14_O2’/U4 and O2/U15_O2’/A25 for the 32 duplexes in RNA supercell for interface 2. (Red lines are standard deviations, blue lines are the distance in crystal structure, black bars give the average distances for every duplex.)

Figure 11.

Distances of center of mass between the interface residues for RNA, for each of the 32 copies of each interface. Black lines show the value from the X-ray structure. Bold blue lines are the average distances between interface centers of mass.

4.2 Crystal interfaces for DNA

The five interfaces for DNA are shown in Fig. 12 and Table 6. In interface 1 the decamer helices are stacked one on top of another along the z-axis leading to co-axial stacking. The second and third interfaces are along the x axis with P3, P4 facing P17, P18, and P8, P9 facing P12, P13, respectively. For the fourth and fifth interfaces, P6 and P16 are in close proximity to the inter–helix gaps of neighboring duplexes. The surface area buried by these contacts is 1218 Å2, which is 31% of the total surface area of an isolated duplex.

Figure 12.

Same as Fig. 9, but for DNA.

Table 6.

Van der Waals contacts and interactions between symmetry-related helices in DNA. The data in parentheses are standard deviations.

| Type | Interactions | Area(Å2) | Atom 1 | Symmetry operator |

Atom 2 | Xtal. dist. | Cryst. Sim. dist. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | terminal –terminal |

199.9 | N3/C11 | x,y,z−1 | N3/G20 | 3.49 | 3.51 (0.23) |

| O3’/G10 | O5’/C1 | 3.37 | 3.63 (0.89) | ||||

| 2 | backbone– minor groove |

154.2 | OP1/A3 | x−1/2, −y+1/2, −z |

O4’/A17 | 3.65 | 4.77 (1.08) |

| P/A3 | P/A17 | 6.49 | 7.59 (1.53) | ||||

| P/T4 | P/A17 | 4.65 | 5.79 (1.93) | ||||

| OP1/T4 | OP2/A17 | 3.88 | 5.83 (1.33) | ||||

| OP2/T4 | O5’/A17 | 3.79 | 4.62 (0.96) | ||||

| 3 | backbone– backbone |

102.7 | OP1/A13 | x−1/2, −y+1/2, −z+1 |

OP2/C9 | 3.90 | 5.24 (1.39) |

| O3’/G12 | O5’/T8 | 3.93 | 5.23 (1.45) | ||||

| P/A13 | P/C9 | 5.15 | 6.65 (1.29) | ||||

| P/G12 | P/T8 | 8.25 | 7.12 (1.08) | ||||

| 4 | minor groove –major groove |

76.1 | P/G6 | −x+1/2, −y,z−1/2 |

O3’/G20 | 3.74 | 4.29 (1.05) |

| OP2/G6 | O3’/G20 | 2.68 | 3.37 (1.00) | ||||

| P/G6 | P/G20 | 8.07 | 8.36 (1.22) | ||||

| P/G12 | P/G6 | 6.28 | 7.71 (1.10) | ||||

| 5 | major groove –major groove |

76.0 | P/G16 | −x+1/2, −y+1, z−1/2 |

O5’/C1 | 3.40 | 4.63 (1.14) |

| O3’/G10 | P/G16 | 3.93 | 3.96 (0.77) | ||||

| P/G16 | P/G2 | 6.29 | 8.09 (1.03) | ||||

| P/G10 | P/G16 | 8.36 | 7.57 (0.96) |

Hydrated Mg2+ frequently mediate intermolecular contacts between adjacent DNA molecules. Evidence from molecular dynamics simulations by Hartmann[35] support that Mg2+ bound to the DNA major groove have an effect on DNA structure and dynamics; hydrated Mg2+ often forms a stable intra-strand cross-link between the two purines and increases the BII population. Li et al.[55] have argued that the binding of Mg2+rigidifies DNA compared to Na+.

Two Mg(H2O)62+clusters are identified in the DNA deposited structure, located at G16•A17 in the minor groove and at G6•A7 in the major groove, adjacent to two of the BII sites at P7 and P17; these are shown in Fig. 13. These sites are also highly occupied with Mg2+ in the simulation. Additional ion sites must be present to neutralize the total charge, but were not modeled in the deposited structure. Other relatively-well localized sites for hydrated magnesium are evident in the simulation, both in the grooves and near phosphate positions (see Fig. 13). Almost all of the Mg2+ ions remain coordinated to six water molecules throughout the simulation: for 0.58% of the time, the ions have 5 waters in the first coordination shell. All of the ions have approximately the same diffusion constant (about 3 × 10−9 cm2/s), so that the ions initially placed in crystallographic density have the same mobility as those randomly added to achieve neutrality. A fuller analysis of ion distributions probably requires additional simulations, preferably with less lattice distortion than that seen here, since magnesium ions are involved with bridging interactions between duplexes as well.

Figure 13.

Cartoon view of the 1D23 crystal structure, showing the two identified Mg2+ ions as green spheres with attached water molecules (smaller red spheres). The mesh structure shows the Mg2+ distribution from the simulation.

The analysis of the deformations in the distances between the centers of mass between the interface residues (Fig. 14) implicates all interfaces in crystal lattice deformations. The coaxial stacking (interface 1) shows small fluctuations and a compression by about 0.5 Å, whereas the other interfaces increase in average length by up to 0.5 Å, and individual copies exhibit much larger variations from the mean. These results are consistent with the larger average values and fluctuations for individual contacts that are shown in Table 6. Deviations from the mean behavior are much greater for DNA than for RNA (compare Figs. 11 and 14.)

Figure 14.

Distances between the centers of mass between the interface residues for DNA. Black lines show the value from the X-ray structure. Bold blue lines are the average distances between interface centers of mass.

The displacements of the centers of mass from their ideal positions (averaged over time) for each duplex in the supercell are shown in Fig. 15. The average distance of each point from its ideal position is 0.37 Å for RNA and 1.77 Å for DNA. (For comparison, in a recent simulation of lysozyme, the mean deviations of the proteins from their ideal lattice positions was 0.27 Å.) Such large translations of some duplexes in the supercell correspond to a significant loss of crystal symmetry, which can also be seen in Fig. 2.

5 Conclusions

We have performed crystal simulations of 1D23 and 1RNA in the “supercell” with 32 copies of each duplex, as well as solution simulation of isolated duplexes. As has been seen in earlier studies, the average duplex structures from crystal simulation match the experimental structure much more closely than the average structures from solution simulations with the same force field. There is a general tendency for the solution simulation to flatten the variations in helicoidal parameters seen in the crystal (and, presumably, stabilized by crystal packing interactions.) Fluctuations about the average structure in the crystal simulation are in good agreement with refined B-factors for base atoms, but are somewhat higher for the sugar-phosphate backbone atoms; fluctuations in solution are considerably higher than in the crystal lattice.

On the other hand, the contacts that stabilize the crystal lattice are not extensive in these crystals, especially for DNA, and our simulations show a progressive deformation of the lattice, such that the duplexes move away from the “proper” positions in the supercell by 1 to 2 Å. This is more true for DNA than for RNA, perhaps by virtue of having fewer hydrogen bonds between duplexes to stabilize the lattice. Another factor may simply be the shorter simulation time for RNA. The results of the present work represent the largest all-atom crystal “supercell “ simulations of nucleic acid to date, and provide a clearer understanding of the structural and dynamical parameters for RNA and DNA crystals. They also offer insights into a new challenge for force-field simulations in crystals and non-crystalline applications with weak interactions between chains. Future studies are planned to investigate depenencies on force fields, water models, and methods of representing ion interactions.

Highlights.

-

*

Crystal simulations of nucleic acids reproduce many aspects of their structures

-

*

Lattice packing is more difficult to simulate

-

*

New insights are gained into the differences between crystal and solution

6 Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant GM103297. We thank Tom Cheatham for useful discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kim HS, Mhin BJ, Yoon CW, Wang CX, Kim KS. A theoretical study of a Z-DNA crystal: Structure of counterions, water and DNA molecules. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 1991;12:214–219. [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacKerell AD, Jr, Wiórkiewicz-Kuczera J, Karplus M. An all-atom empirical energy function for the simulation of nucleic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:11946–11975. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheatham TE, Case DA. Twenty-five years of nucleic acid simulations. Biopolymers. 2013;99:969–977. doi: 10.1002/bip.22331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheatham TE, III, Miller JL, Fox T, Darden TA, Kollman PA. Molecular dynamics simulations on solvated biomolecular systems: The particle mesh Ewald method leads to stable trajectories of DNA, RNA and proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:4193–4194. [Google Scholar]

- 5.York DM, Yang W, Lee H, Darden T, Pedersen LG. Toward the accurate modelling of DNA: The importance of long-range electrostatics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:5001–5002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee H, Darden T, Pedersen L. Accurate crystal molecular dynamics using particle-mesh-Ewald: RNA dinucleotides – ApU and GpC. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1995:229–235. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee H, Darden TA, Pedersen LG. Molecular dynamics simulations studies of a high resolution Z-DNA crystal. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;102:3830–3834. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babin V, Baucom J, Darden TA, Sagui C. Molecular dynamics simulations of DNA with polarizable force fields: Convergence of an ideal B-DNA structure to the crystallographic structure. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:11571–11581. doi: 10.1021/jp061421r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babin V, Baucom J, Darden TA, Sagui C. Molecular dynamics simulations of polarizable DNA in crystal environment. Int. J. Quant. Chem. 2006;106:3260–3269. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gong Z, Xiao Y, Xiao Y. RNA stability under different combinations of Amber force fields and solvation models. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2010;28:431–441. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2010.10507372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Babin V, Wang D, Rose RB, Sagui C. Binding polymorphism in DNA bound state of the Pdx1 homeodomain. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013;9:e1003160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuzmanic A, Zagrovic B. Dependence of protein crystal stability of residue charge states and ion content of crystal solvent. Biophys. J. 2014;106:677–686. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahlstrom LS, Miyashita O. Packing interface energetics in different crystal forms of the lambda Cro dimer. Proteins. 2014;82:1128–1141. doi: 10.1002/prot.24478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu Z, Jiang J, Sandler SI. Water in hydrated orthorhombic lysozyme crystal: Insight from atomistic simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;129:075105. doi: 10.1063/1.2969811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu Z, Jiang J. Molecular dynamics simulations for water and ions in protein crystals. Langmuir. 2008;24:4215–4223. doi: 10.1021/la703591e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu Z, Jiang J. Assessment of biomolecular force fields for molecular dynamics simulations in a protein crystal. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;31:371–380. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cerutti DS, Le Trong I, Stenkamp RE, Lybrand TP. Dynamics of the streptavidin-biotin complex in solution and in its crystalline lattice: Distinct behavior revealed by molecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:6971–6985. doi: 10.1021/jp9010372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cerutti DS, Freddolino PL, Duke RE, Jr, Case DA. Simulations of a protein crystal with a high resolution X-ray structure: Evaluation of force fields and water models. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:12811–12824. doi: 10.1021/jp105813j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janowski PA, Cerutti DS, Holton J, Case DA. Peptide crystal simulations reveal hidden dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:7938–7948. doi: 10.1021/ja401382y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuzmanic A, Pannu NS, Zagrovic B. X-ray refinement significantly underestimates the level of microscopic heterogeneity in biomolecular crystals. Nature Commun. 2014;5:3220. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xue Y, Skrynnikov NR. Ensemble MD simulations restrained vi crystallographic data: Accurate structure leads to accurate dynamics. Prot. Sci. 2014;23:488–507. doi: 10.1002/pro.2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grzeskowiak K, Yanagi K, Prive GG, Dickerson RE. The structure of B-helical C-G-A-T-C-G-AT-C-G and comparison with C-C-A-A-C-G-T-T-G-G. The effect of base pair reversals. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:8861. doi: 10.2210/pdb1d23/pdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dock-Bregeon AC, Chevrier B, Podjarny A, Moras D, De Bear JS, Gough GR, Gilham PT, Johnson JE. High resolution structure of the RNA duplex [U(U-A)6A]2. Nature. 1988;335:375–379. doi: 10.1038/335375a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dock-Bregeon AC, Chevrier B, Podjarny A, Johnson J, De Bear JS, Gough GR, Gilham PT, Moras D. Crystallographic structure of an RNA helix: [U(U-A)6A]2. J. Mol. Biol. 1989;209:459–474. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Besseová I, Otykpka M, Réblová K, Sponer J. Dependence of A-RNA simulations on the choice of force field and salt strength. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009;11:10701–10711. doi: 10.1039/b911169g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Besseova I, Banas P, Kuhrova P, Kosinova M, Otyepka M, Sponer J. Simulations of A-RNA duplexes. The effect of sequence, solute force field, water model, and salt concentration. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:9899–9916. doi: 10.1021/jp3014817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dixit SB, Beveridge DL, Case DA, Cheatham TE, III, Giudice E, Lankas F, Lavery R, Maddocks JH, Osman R, Sklenar H, Thayer KM, Varmai P. Molecular dynamics simulations of the 136 unique tetranucleotide sequences of DNA oligonucleotides. II. Sequence context effects on the dynamical structures of the 10 unique dinucleotide steps. Biophys. J. 2005;89:3721–3740. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.067397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lavery R, Zakrzewska K, Beveridge D, Bishop TC, Case DA, Cheatham T, III, Dixit S, Jayaram B, Lankas F, Laughton C, Maddocks JH, Michon A, Osman R, Orozco M, Perez A, Spackova N, Sponer J. A systematic molecular dynamics study of nearest-neighbor effects on base pair and base pair step conformations and fluctuations in B-DNA. Nucl. Acids Res. 2010;38:299–313. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beveridge DL, Cheatham TE, III, Mezei M. The ABCs of molecular dynamics simulations on B-DNA, circa 2012. J. Bioscience. 2012;37:379–397. doi: 10.1007/s12038-012-9222-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pasi M, Maddocks JH, Beveridge D, Bishop TC, Case DA, Cheatham T, III, Jayaram B, Lankas F, Laughton C, Mitchel J, Osman R, Orozco M, Petkeviciute D, Spackova N, Sponer J, Zakrzewska K, Lavery R. microABC: a systematic microsecond molecular dynamics study of tetranucleotide sequence effects in B-DNA. Nucl. Acids Res. 2014 doi: 10.1093/nar/gku855. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perez A, Luque FJ, Orozco M. Dynamics of B-DNA on the microsecond time scale. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14739–14745. doi: 10.1021/ja0753546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pérez A, Luque FJ, Orozco M. Frontiers in molecular dynamics simulations of DNA. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011;45:196–205. doi: 10.1021/ar2001217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teletchea S, Hartmann B, Kozelka J. Discrimination between BI and BII conformational substates of B-DNA based on sugar-base interproton distances. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2004;21:489–494. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2004.10506942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heddi B, Foloppe N, Bouchemal N, Hantz E, Hartmann B. Quantification of DNA BI/BII backbone states in solution. Implications for DNA overall structure and recognition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:9170–9177. doi: 10.1021/ja061686j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guéroult M, Boittin O, Mauffret O, Etchbest C, Hartmann B. Mg2+ in the major groove modulates B-DNA structure and dynamics. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41704. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Case DA, Cheatham TE, III, Darden T, Gohlke H, Luo R, Merz KM, Jr, Onufriev A, Simmerling C, Wang B, Woods R. The Amber biomolecular simulation programs. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1668–1688. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J, Cieplak P, Kollman PA. How well does a restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) model perform in calcluating conformational energies of organic and biological molecules? J. Comput. Chem. 2000;21:1049–1074. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perez A, Marchan I, Svozil D, Sponer J, Cheatham TE, Laughton CA, Orozco M. Refinement of the AMBER force field for nucleic acids: Improving the description of alpha/gamma conformers. Biophys. J. 2007;92:3817–3829. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.097782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zgarbova M, Otyepka M, Sponer J, Mladek A, Banas P, Cheatham TE, Jurecka P. Refinement of the Cornell et al. nucleic acids force field based on reference quantum chemical calculations of glycosidic torsion profiles. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011;7:2886–2902. doi: 10.1021/ct200162x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura J, Klein ML. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horn HW, Swope WC, Pitera JW, Madura JD, Dick TJ, Hura GL, Head-Gordon T. Development of an improved four-site water model for biomolecular simulations: TIP4P-Ew. J. Chem. Phys. 2004;120:9665–9678. doi: 10.1063/1.1683075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joung IS, Cheatham TE. III Determination of alkali and halide monovalent ion parameters for use in explicitly solvated biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:9020–9041. doi: 10.1021/jp8001614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Åqvist J. Ion-water interaction potentials derived from free energy perturbation simulations. J. Phys. Chem. 1990;94:8021–8024. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salomon-Ferrer R, Case DA, Walker RC. An overview of the Amber biomolecular simulation package. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2013;3:198–210. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salomon-Ferrer R, Götz AW, Poole D, Le Grand S, Walker RC. Routine microsecond molecular dynamics simulations with AMBER on GPUs. 2. Explicit solvent particle mesh Ewald. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013;9:3878–3888. doi: 10.1021/ct400314y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beveridge DL, Barreiro G, Byun KS, Case DA, Cheatham TE, Dixit SB, Giudice E, Lankas F, Lavery R, Maddocks JH. Molecular dynamics simulations of the 136 unique tetranucleotide sequences of DNA oligonucleotides. I. Research design and results on d(CpG) Steps. Biophys. J. 2004;87:3799–3813. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.045252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lavery R, Moakher M, Maddocks JH, Petkeviciute D, Zakrzewska K. Conformational analysis of nucleic acids revisited: Curves+ Nucl. Acids Res. 2009;37:5917–5959. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tolbert BS, Miyazaki Y, Barton S, Kinde B, Starck P, Singh R, Bax A, Case DA, Summers MF. Major groove width variations in RNA structures determined by NMR and impact of C-13 residual chemical shift anisotropy and H-1-C-13 residual dipolar coupling on refinement. J. Biomol. NMR. 2010;47:205–219. doi: 10.1007/s10858-010-9424-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mack DR, Chiu TK, Dickerson RE. Intrinsic bending and deformability at the T-A step of CCTT-TAAAGG: A comparative analysis of T-A and A-T steps within A-tracts. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;312:1037–1049. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Poncin M, Hartmann B, Lavery R. Conformational substates in B-DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;226:775–794. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90632-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dickerson RE. Definitions and nomenclature of nucleic acid structure parameters. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1989;6:627–634. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1989.10507726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Faustino I, Pérez A, Orozco M. Toward a consensus view of duplex RNA flexibility. Biophys. J. 2010;99:1876–1885. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.06.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dans PB, Pérez A, Faustino I, Lavery R, Orozco M. Exploring polymorphisms in D-DNA helical conformations. Nucl. Acids Res. 2012;40:10668–10678. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li W, Nordenskiöld L, Mu Y. Sequence-specific Mg2+-DNA interactions: A molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:14713–14720. doi: 10.1021/jp2052568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]