Abstract

Objective

Emergency medical services (EMS) personnel frequently use the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) to assess injured and critically ill patients. This study assessed the accuracy of EMS providers’ GCS scoring as well as the improvement in GCS assessment with the use of a scoring aid.

Methods

This randomized, controlled study was conducted in the emergency department (ED) of an urban, academic trauma center. Emergency medical technicians or paramedics who transported a patient to the ED were randomly assessed one of nine written scenarios, either with or without a GCS scoring aid. Scenarios were created by consensus of expert attending emergency medicine, EMS, and neurocritical care physicians with universal consensus agreement on GCS scores. Chi-square and student’s t-tests were used to compare groups.

Results

Of 180 participants, 178 completed the study. Overall, 73/178 (41%) participants gave a GCS score that matched the expert consensus score. GCS was correct in 22/88 (25%) of cases without the scoring aid. GCS was correct in 51/90 (57%) of cases with the scoring aid. Most (69%) of total GCS scores fell within one point of the expert consensus GCS score. Differences in accuracy were most pronounced in scenarios with a correct GCS of 12 or below. Sub-component accuracy was: eye 62%, verbal 70%, and motor 51%.

Conclusion

In this study, 60% of EMS participants provided inaccurate GCS estimates. Use of a GCS scoring aid improved accuracy of EMS GCS assessments.

Introduction

Background and importance

First introduced in 1974, the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is commonly used to describe the level of consciousness in and to predict outcomes of a wide variety of patients, including those in the prehospital setting.1–3 Prehospital providers use baseline and changes in GCS assessments to indicate the severity of injuries or illness, and to aid in patient triage.2,4 In addition to its clinical utility, the GCS is commonly used in research, both to ascertain participant eligibility and as an outcomes assessment or adjustment for baseline severity.5

Since the GCS can play a role in the initial and ongoing treatment of the patient, quick and accurate evaluation is necessary. The ability of prehospital providers to accurately score the GCS has not been well reported, yet anecdotally they are often criticized for inaccurate GCS assessment. There are only limited data characterizing the degree of EMS GCS inaccuracy.6 Furthermore, inter-rater reliability of GCS scoring is known to be low, including in the prehospital setting.4,7,8 An aid to facilitate quick recall of the GCS in real-time could improve scoring accuracy.9

Goals of this investigation

This study assessed the accuracy of EMS providers’ GCS scoring of written scenarios and estimated the potential for a GCS scoring aid to improve accuracy. We hypothesized that providers assisted by a GCS scoring table would assess GCS more accurately than providers who did not have the aid available.

Methods

Study design and setting

This randomized controlled study of the utility of a GCS scoring table aid was conducted in the Emergency Department of an urban, academic level 1 trauma center. The University of Cincinnati Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Selection of participants

Participants were emergency medical technicians or paramedics who had transported a patient to the ED. We enrolled subjects during times of study personnel availability, which included weekdays, nights, and weekends. Providers were only permitted to participate once and had to be over the age of 18 years. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and all participants provided informed consent.

Methods of measurement

Nine standardized brief patient scenarios (Supplemental Table) were modified from three widely used EMS textbooks.10–12 Attending physicians specializing in emergency medicine, EMS, and neurocritical care reviewed the scenarios and provided revisions until there was universal agreement on GCS scores. The scenarios depicted patients with GCS scores corresponding to mild (GCS 13–15), moderate (GCS 9–12), and severe (GCS 3–8) traumatic brain injuries. The test scenarios and expert consensus GCS scores were verified by an independent team of paramedic instructors.

Scenarios with or without the scoring table were placed into sequentially numbered, sealed envelopes for distribution to participants. Each participant was randomly assigned to determine GCS scores on one of the nine scenarios, with or without the scoring table. No blinding methods were used after randomization. Participants were asked to provide the total GCS score of the patient in the scenario, as well as the eye, verbal, and motor subcomponent scores. The participants’ demographic information was collected, including experience, level of training, and EMS practice habits.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the absolute agreement between the participants’ assigned GCS scores and the correct GCS score determined by the attending physician review. Secondary outcomes included the frequency of scores falling within one point of the correct score, accuracy of sub-component scores, and accuracy for the different levels of severity.

Sample size

A sample size of 90 in each group would have 80% power to detect an absolute difference of 15% of the proportion of subjects able to correctly determine the GCS with or without the GCS scoring aid when alpha is set to 0.05 and conservatively assuming a wide standard deviation.

Data management and analysis

The one:one randomization sequence was generated using nQuery Adviser 7.0 (Statistical Solutions, Boston, MA) and designed to ensure equal distribution of the nine scenarios among those receiving the GCS aid and those not receiving the aid. Participants’ responses were entered into an electronic database (REDCap, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN). Out of range GCS scores were queried and confirmed. Missing data were minimal and left missing. We compared participant GCS with expert consensus GCS ratings using the Chi-Square Test to or Fisher’s Exact Test, as appropriate, to test for differences in proportions and calculated 95% confidence intervals for the effect size. We adjusted for multiple comparisons using Sidak’s method.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Graphics were created using R (gplots). Differences in means and proportions and 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

Results

Characteristics of study subjects

Between April 2013 and June 2013, 261 subjects were screened; sixteen declined participation and 65 did not meet inclusion criteria. Of 180 subjects enrolled, two participants were excluded due to incomplete GCS scores, leaving 178 cases in the analysis (Supplemental Figure).

Participant characteristics are described in Table 1. About half (52%) were paramedics and participants were drawn from 41 different EMS departments or agencies. The EMS agencies are diverse and include rural, suburban, and urban settings, paid and volunteer staffing models, and annual call volumes ranging from <500 to >55000. The mean length of experience was 12 years (SD 8). Most (70%) reported they had been refreshed on GCS material through a course, recertification, or training within the past year and 56% stated they consistently use some sort of aid in the field to help determine the GCS score. The two study arms were well matched in experience and certification levels, and no protocol deviations occurred.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

| No table aid (n=88) |

Table Aid (N=90) |

Total (n=178) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age – Mean (SD) | 37 | (10) | 36 | (9) | 36 | (9) | |

| Race – N (%) | |||||||

| White | 72 | (81.8) | 76 | (84.4) | 148 | (83.1) | |

| Black/African American | 15 | (17.0) | 11 | (12.2) | 26 | (14.5) | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (2.2) | 2 | (1.1) | |

| Other | 1 | (1.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.6) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.1) | 1 | (0.6) | |

| Male – N (%) | 80 | (90.9) | 77 | (85.6) | 157 | (88.2) | |

| Level of EMS certification – N (%) | |||||||

| EMT-Basic | 44 | (50.0) | 39 | (43.3) | 83 | (46.9) | |

| EMT-Intermediate | 2 | (2.3) | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (1.1) | |

| Paramedic | 42 | (47.7) | 51 | (56.7) | 93 | (52.0) | |

| Years of experience – Mean (SD) | 12 | (8) | 11 | (7) | 12 | (8) | |

| Refreshed on GCS material within the past year – N (%) | 58 | (65.9) | 67 | (74.4) | 125 | (70.2) | |

| EMS instructor – N (%) | 6 | (6.8) | 7 | (7.8) | 13 | (7.8) | |

| Use aid to determine the GCS in the field – N (%) | 54 | (61.4) | 45 | (50.0) | 99 | (50.0) | |

EMT: Emergency Medical Technician; EMS: Emergency Medical Services; GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale

Primary Outcome

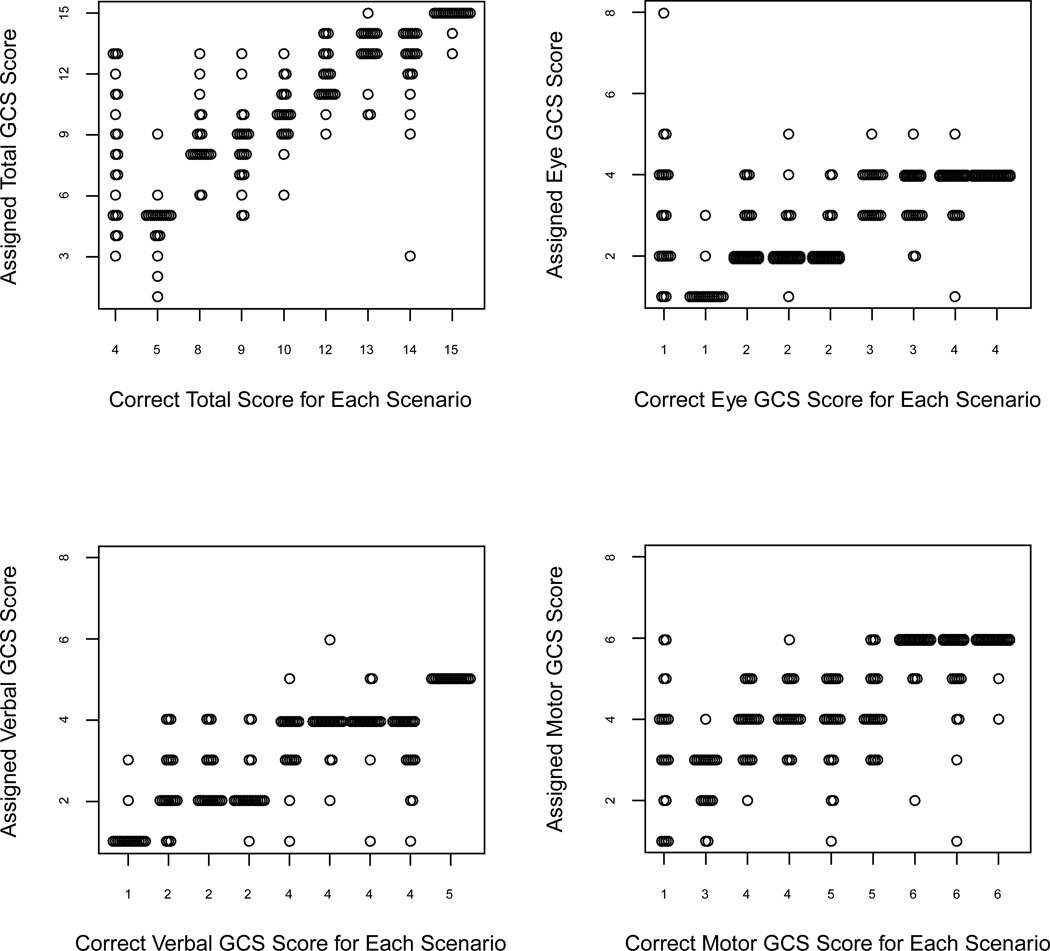

Overall, 73/178 (41%) participants gave a GCS score that matched the correct GCS score (Table 2, Figure 1). Among participants who did not receive the standard GCS scoring table as an aid, the GCS was correct in 22/88 (25%) of cases compared to 51/90 (57%) in those who did receive the table aid (difference in proportions 32%, 95% CI 18–46%).

Table 2. Scoring of patient scenarios by EMS providers.

Results are presented as the proportion of absolutely correctly assigned composite and component Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score and further stratified by mild, moderate, and severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) scenarios.

| Total (n=178) | No table aid (n=88) |

Table aid (n=90) | 95% CI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | % Difference | Lower | Upper | |

| All scenarios | |||||||||

| Total GCS | 73 | (41.0) | 22 | (25.0) | 51 | (56.7) | 31.9 | 18.3 | 45.6 |

| Eye GCS | 110 | (61.8) | 38 | (43.2) | 72 | (80.0) | 37.3 | 24.1 | 50.5 |

| Verbal GCS | 125 | (70.2) | 48 | (54.5) | 77 | (85.6) | 31.6 | 19.0 | 44.3 |

| Motor GCS | 90 | (50.6) | 27 | (30.7) | 63 | (70.0) | 39.7 | 26.2 | 53.1 |

| Mild TBI scenarios (GCS 13–15) | |||||||||

| Total GCS | 32 | (54.2) | 13 | (44.8) | 19 | (63.3) | 14.3 | −6.1 | 34.6 |

| Eye GCS | 41 | (69.5) | 16 | (55.2) | 25 | (83.3) | 18.5 | −6.5 | 43.5 |

| Verbal GCS | 47 | (79.7) | 21 | (72.4) | 26 | (86.7) | 28.2 | 5.7 | 50.6 |

| Motor GCS | 44 | (74.6) | 17 | (58.6) | 27 | (90.0) | 29.3 | 6.1 | 52.5 |

| Moderate TBI scenarios (GCS 9–12) | |||||||||

| Total GCS | 17 | (28.8) | 3 | (10.3) | 14 | (46.7) | 31.4 | 10.5 | 52.3 |

| Eye GCS | 37 | (62.7) | 12 | (41.4) | 25 | (83.3) | 34.9 | 13.1 | 56.8 |

| Verbal GCS | 41 | (69.5) | 15 | (51.7) | 26 | (86.7) | 36.3 | 15.3 | 57.3 |

| Motor GCS | 21 | (35.6) | 6 | (20.7) | 15 | (50.0) | 40.0 | 17.4 | 62.6 |

| Severe TBI scenarios (GCS 3–8) | |||||||||

| Total GCS | 24 | (40.0) | 6 | (20.0) | 18 | (60.0) | 40.0 | 16.9 | 63.1 |

| Eye GCS | 32 | (53.3) | 10 | (33.3) | 22 | (73.3) | 42.0 | 19.6 | 64.3 |

| Verbal GCS | 37 | (61.7) | 12 | (40.0) | 25 | (83.3) | 43.3 | 21.3 | 65.4 |

| Motor GCS | 25 | (41.7) | 4 | (13.3) | 21 | (70.0) | 56.7 | 36.2 | 77.1 |

Figure 1.

Dot-plot of assigned composite and component Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores for each scenario. Each circle represents the score assigned by a single respondent.

Secondary Outcomes

Overall, 123/178 (69%) of scores fell within one point of the correct GCS score. There was equal likelihood to overestimate (29.2%) and underestimate (29.8%) the total GCS score. More scores were correct within one point in the group who received the table aid than the group who did not receive the table aid (82.2% v 55.7%; difference 26.5%, 95% CI 13.5–39.6%). The mean difference between actual and participant-assigned GCS scores for the group without the table was 2.6 and the mean participant assigned GCS scores for the group with the table was 2.1 (difference of means 0.5, 95% CI −0.3 – 1.3). The difference in accuracy between the two groups was most pronounced in the moderate (GCS 9–12) and severe (GCS 3–8) scenarios (Table 2, Figure 1). Twelve (7%) participants gave sub-component scores that are not possible on the scale. Eye component accuracy improved from 43% without the table aid to 80% with the table aid, the verbal from 55% to 86%, and motor from 31% to 70% (Table 2, Figure 1).

Limitations

Scoring a written scenario in a controlled environment and assigning a GCS score during the immediate evaluation and treatment phase of an acutely ill or injured patient are inherently different. While we have mirrored previously used methodologies,9,13 our approach may overestimate accuracy because the EMS providers are not subject to the task saturation of clinical care. Conversely, it is possible that the information gained from examining a live patient could be more useful than that presented in a written scenario, which could improve the accuracy of GCS estimates.

We did not record whether subjects sought help in scoring the scenarios, either from another EMS provider or from their personal GCS scoring aides, although no such activity was witnessed. Use of a scoring aid in the group not given one as part of the study would bias towards improved accuracy, and failure to use the aid provided would cause the opposite. In either case, the actual effect sizes would be greater than we observed.

While we identified a deficiency in GCS scoring by EMS providers, we are unable to speculate as to the reasons such a deficiency exists. Use of a scoring aid does improve accuracy, but discovery of other potential causes—and solutions—would be useful.

Discussion

These results suggest that GCS assessment with scoring table improves the accuracy of EMS providers’ GCS scoring of patients using written scenarios. However, even with use of a GCS table, accuracy of GCS scoring by EMS providers was low.

The GCS has been criticized as somewhat complex and the fundamental utility and appropriateness of GCS scores in Emergency Medicine, and prehospital care by proxy, has been challenged.14 We agree that GCS is imperfect and we support calls for a better tool. However, despite these prior criticisms,14 GCS is still the tool that has been universally adopted in clinical care. Until the GCS can be replaced, accurate scoring using the GCS should be emphasized. The inability of EMS providers to accurately assess an injured patient and communicate the findings is a problem regardless of the tool used.

Our data empirically quantify the inaccuracy, offering providers information that should be useful in interpreting a prehospital GCS. Clinically, a one-point discrepancy in the GCS score may be acceptable, and when a scoring table aid was made available to providers, 82% of scores were within one point of the correct score. In other situations, even a one point error may prompt inappropriate field triage to a trauma center, exclusion from a clinical trial, or consideration of a procedure (i.e. endotracheal intubation). Providers were just as likely to overestimate and underestimate scores, and the magnitude of the difference was frequently enough to change the assigned category in the mild/moderate/severe classification scheme (Figure 1).

While our findings of inaccuracy when relying on memory alone are, unfortunately, not unique,9 we show that having a scoring table aid readily available more than doubles (25% to 57%) the number of accurate scores. To our knowledge, this is the first intervention shown to improve GCS scoring accuracy. Based on our observations, EMS providers should be given GCS scoring cards with real-time use strongly encouraged.

Some health care providers have advocated abandonment of the full GCS and suggest simplifications or using only the motor component.15–18 In our sample, the motor score was the least reliable of the subcomponents. Proposed alternatives to the GCS that simplify assessment of consciousness include the FOUR score and the Emergency Coma Scale.19,20 However, these scoring methods may also suffer from accuracy limitations because the eye and motor components are similar to the GCS. Additionally, many of the papers that compare GCS to a newer tool of mental status assessment rely on retrospectively recorded prehospital GCS values as the criterion standard.18,19 Our results do not support abandoning the full GCS in favor of these alternatives.

Our findings provide the key insights regarding the inaccuracy of GCS scoring by EMS and support the need for improved tools for evaluating out-of-hospital patients with neurologic emergencies. Until a new method of evaluating altered mental status in the setting of trauma is developed, validated, and adopted, use of a GCS scoring aid may help to improve the accuracy of the EMS GCS assessments.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure for online publication: CONSORT flow diagram of subjects.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part by an Institutional Clinical and Translational Science Award, NIH/NCRR Grant Number 5UL1RR026314-03.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This work was presented at the National Association of EMS Physicians annual meeting as a moderated poster (January 2014, Tucson AZ).

No authors have a conflict of interest.

ALF, JTM and CJL conceived and designed the study. ALF implemented the study and conducted all data collection. KWH conducted the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results. ALF drafted the manuscript and all authors provided critical review and revisions for intellectual content. All authors approved the final version. ALF takes responsibility for the manuscript as a whole.

Contributor Information

Amanda Lynn Feldman, Northeast Ohio Medical University, working with the University of Cincinnati Department of Emergency Medicine at the time of enrollment, amandaf@bgsu.edu.

Kimberly Ward Hart, University of Cincinnati Department of Emergency Medicine, hartkb@uc.edu.

Christopher John Lindsell, University of Cincinnati Department of Emergency Medicine, lindsecj@uc.edu.

Jason T. McMullan, University of Cincinnati Department of Emergency Medicine, mcmulljo@uc.edu.

References

- 1.Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2:81–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis DP, Serrano JA, Vilke GM, et al. The predictive value of field versus arrival Glasgow Coma Scale score and TRISS calculations in moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 2006;60:985–990. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000205860.96209.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badjatia N, Carney N, Crocco TJ, et al. Guidelines for prehospital management of traumatic brain injury 2nd edition. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2008;12(Suppl 1):S1–S52. doi: 10.1080/10903120701732052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kerby JD, MacLennan PA, Burton JN, McGwin G, Jr, Rue LW., 3rd Agreement between prehospital and emergency department glasgow coma scores. J Trauma. 2007;63:1026–1031. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318157d9e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bulger EM, May S, Brasel KJ, et al. Out-of-hospital hypertonic resuscitation following severe traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2010;304:1455–1464. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bazarian JJ, Eirich MA, Salhanick SD. The relationship between pre-hospital and emergency department Glasgow coma scale scores. Brain Inj. 2003;17:553–560. doi: 10.1080/0269905031000070260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baez AA, Giraldez EM, De Pena JM. Precision and reliability of the Glasgow Coma Scale score among a cohort of Latin American prehospital emergency care providers. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2007;22:230–232. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00004726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill MR, Reiley DG, Green SM. Interrater reliability of Glasgow Coma Scale scores in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:215–223. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(03)00814-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane PL, Baez AA, Brabson T, Burmeister DD, Kelly JJ. Effectiveness of a Glasgow Coma Scale instructional video for EMS providers. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2002;17:142–146. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00000364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsieh A, Boone K. The Paramedic Companion: A Case-based Worktext. Boston: McGraw-Hill; 2008. pp. 240–249. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caroline NL. Study Guide for Emergency Care in the Streets. 4th ed. Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 1991. p. 94. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalton A, Walker RA. Mosby's Paramedic Refresher and Review: A Case Studies Approach. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1999. pp. 295–297. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heim C, Schoettker P, Gilliard N, Spahn DR. Knowledge of Glasgow coma scale by air-rescue physicians. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009;17:39. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-17-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green SM. Cheerio, laddie! Bidding farewell to the Glasgow Coma Scale. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:427–430. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gill M, Martens K, Lynch EL, Salih A, Green SM. Interrater reliability of 3 simplified neurologic scales applied to adults presenting to the emergency department with altered levels of consciousness. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:403–407. 7 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Healey C, Osler TM, Rogers FB, et al. Improving the Glasgow Coma Scale score: motor score alone is a better predictor. J Trauma. 2003;54:671–678. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000058130.30490.5D. discussion 8–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gill M, Steele R, Windemuth R, Green SM. A comparison of five simplified scales to the out-ofhospital Glasgow Coma Scale for the prediction of traumatic brain injury outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:968–973. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson DO, Hurtado TR, Liao MM, Byyny RL, Gravitz C, Haukoos JS. Validation of the Simplified Motor Score in the out-of-hospital setting for the prediction of outcomes after traumatic brain injury. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wijdicks EF, Bamlet WR, Maramattom BV, Manno EM, McClelland RL. Validation of a new coma scale: The FOUR score. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:585–593. doi: 10.1002/ana.20611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi C, Okudera H, Origasa H, et al. A simple and useful coma scale for patients with neurologic emergencies: the Emergency Coma Scale. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure for online publication: CONSORT flow diagram of subjects.