Abstract

Background & Aims

We investigated the prevalence of germline mutations in APC, ATM, BRCA1, BRCA2, CDKN2A, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PALB2, PMS2, PRSS1, STK11, and TP53 in patients with pancreatic cancer.

Methods

The Ontario Pancreas Cancer Study enrolls consenting participants with pancreatic cancer from a province-wide electronic pathology database; 708 probands were enrolled from April 2003 through August 2012. To improve precision of BRCA2 prevalence estimates, 290 probands were randomly selected from 3 strata, based on family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, or neither. Germline DNA was analyzed by next-generation sequencing using a custom multiple-gene panel. Mutation prevalence estimates were calculated from the sample for the entire cohort.

Results

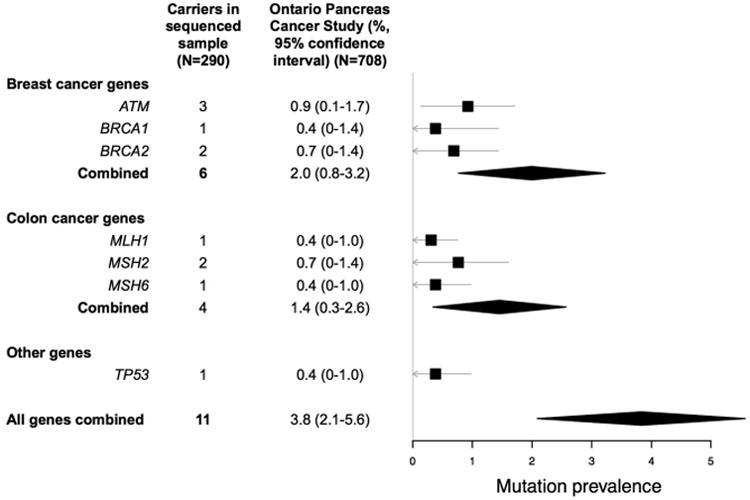

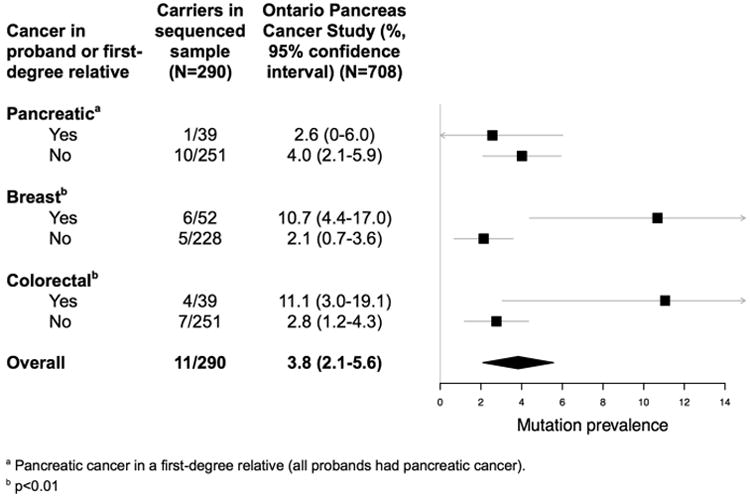

Eleven pathogenic mutations were identified: 3 in ATM, 1 in BRCA1, 2 in BRCA2, 1 in MLH1, 2 in MSH2, 1 in MSH6, and 1 in TP53. The prevalence of mutations in all 13 genes was 3.8% (95% confidence interval, 2.1%–5.6%). Carrier status was significantly associated with breast cancer in the proband or first-degree relative (P<.01), and colorectal cancer in the proband or first-degree relative (P<.01), but not family history of pancreatic cancer, age of diagnosis, or stage at diagnosis. Of patients with a personal or family history of breast and colorectal cancer, 10.7% (4.4%–17.0%) and 11.1% (3.0%–19.1%) carried pathogenic mutations, respectively.

Conclusions

A small but clinically important proportion of pancreatic cancer is associated with mutations in known predisposition genes. The heterogeneity of mutations identified in this study demonstrates the value of using a multiple-gene panel in pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: cancer risk, familial pancreatic cancer, pancreatic cancer genetics

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is a deadly malignancy. Since symptoms generally signal advanced disease1, only about 20% present with localized disease that may be amenable to curative surgical resection2. As a result, PC carries a bleak prognosis; the five-year survival rate is 6%, only a slight improvement from 2% in the 1970s3. Approximately 40,000 Americans will die of PC in 2014, making this malignancy the fourth most common cause of cancer death in men and women3. New screening and treatment strategies to reduce deaths from PC are urgently needed.

A subset of PC is caused by highly penetrant germline mutations that cause well-characterized cancer syndromes. Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome is caused by heterozygous germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. In addition to breast and ovarian cancer, BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers also face an increased risk of prostate cancer and PC4, 5. The risk of PC among carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations has been estimated to be between four- and seven-fold greater than the general population4-6.

Lynch syndrome, also called hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, is caused by heterozygous germline mutations in the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2. MMR mutation carriers face an elevated risk of colorectal, duodenal, endometrial, urogenital tract, brain, hepatobiliary, and PC7-9. MMR gene mutation carriers have been estimated to develop PC at approximately eight times the rate of the general population10.

Other familial cancer syndromes and genes impart increased risk of PC. These include familial adenomatous polyposis, familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome, hereditary pancreatitis, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, and Li-Fraumeni syndrome, which are caused by mutations in APC, CDK2NA, PRSS1, STK11, and TP53, respectively1, 11. Recently, ATM and PALB2, two genes that increase risk of breast cancer, were associated with familial PC12, 13.

Identifying germline mutations in genes that increase risk of PC has important ramifications for the patient and their blood relatives. PC patients carrying these mutations may benefit from experimental and targeted therapies, as proposed with PARP inhibitors and platinum-based chemotherapy in PC patients with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations14, 15. Unaffected relatives who also carry mutations may be candidates for investigational PC screening protocols16, 17. Most importantly, patients and relatives who carry mutations can benefit from well-established targeted extra-pancreatic cancer screening protocols and interventions, such as prophylactic mastectomy and salpingooopherectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers18, 19, and more intensive colorectal cancer screening and management in Lynch and familial adenomatous polyposis syndromes20.

The goal of this study was to determine the prevalence of germline mutations in genes that increase risk of PC in a population-based cohort of PC patients and to determine which clinical characteristics are associated with mutation carrier status.

Methods

Patients

Probands were selected from the Ontario Pancreas Cancer Study (OPCS), which has been described previously21. The OPCS is a population-based registry that contacts all patients in Ontario with a pathological diagnosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma from a province-wide electronic pathology reporting system. Consenting participants answer questionnaires, agree to a review of medical records, and provide biospecimens (blood, saliva, and access to biopsies and resections). OPCS probands recruited between April 2003 and August 2012 with available blood or saliva samples were included in this study. The research ethics board of Mount Sinai Hospital approved this study.

Patient sampling procedure

We aimed to detect at least one mutation for any gene with mutations in at least one percent of pancreatic cancer. To achieve this goal with at least 95% power, a sample size of 290 patients was selected. The subset of 290 probands was randomly selected from the OPCS using a stratified random sampling strategy to maximize the precision for the population estimate of BRCA2 mutation prevalence, since BRCA2 was the only gene that we expected to be frequently mutated. Family history of pancreatic, breast, or ovarian cancer was expected to modulate the prevalence of BRCA2 mutations, so probands were stratified according to family history of cancer. The three strata were: PC in a first, second, or third degree relative; breast or ovarian cancer in a first, second or third degree relative without family history of PC; or no family history of pancreatic, breast, or ovarian cancer in a first, second or third degree relative. The sampling weight for each strata was defined such that it minimized the variance estimate of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation prevalence estimates following the approach proposed by Choi and Briollais22. Probands with known mutations were included in the randomization. A control subject without a history of cancer was sequenced along with the 290 PC probands to assist with variant filtering.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) and bioinformatics

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes using organic solvent isolation or column-based purification methods. A custom targeted capture kit was designed using NimbleDesign (NimbleGen Inc., Madison, U.S.A.) that targeted the exonic and splice site regions of 385 genes previously associated with cancer for use in the clinical laboratory at Mount Sinai Hospital. Libraries were created using the SeqCap EZ Library (NimbleGen Inc., Madison, U.S.A.) and KAPA Library Preparation Kits (Kapa Biosystems, Inc., Wilmington, U.S.A.) according to the manufacturers' protocols. NGS was performed on Illumina HisSeq 2500 platforms (Illumina Inc., San Diego, U.S.A.). Bases were called with default settings using Illumina BCLFAST2 Conversion Software (v.1.8.4, Illumina Inc., San Diego, U.S.A). Sequencing reads were aligned to the reference genome hg19 using the Burrows-Wheels Aligner (v.0.6.2-r126)23. Picard (v1.79, http://picard.sourceforge.net, accessed 1 February 2014) removed duplicate reads. The Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) (v2.0-25-gf27c683)24 was used to detect single nucleotide substitutions and small insertions and deletions, using best practices from the GATK website (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/, accessed 1 February 2014). To maximize sensitivity to detect variants, no variant quality filters were applied. ANNOVAR25 and in-house scripts annotated variants.

Variant characterization

Variants in APC, ATM, BRCA1, BRCA2, CDKN2A, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PALB2, PMS2, PRSS1, STK11, and TP53 were considered for analysis if they were: a) called as non-reference by GATK; b) predicted to affect protein sequence or the splice site (i.e. +/- 5 base pairs); c) had an allele frequency of less than 1% in the 1000 Genome project26, dbSNP13827, and NHLBI Exome Variant Server ESP6500 dataset (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/, accessed 1 February 2014); and d) were not present in the control subject who was sequenced simultaneously with the cohort.

Rare nonsynonymous variants were classified as either pathogenic, benign, or variants of unknown significance (VUS). For BRCA1, BRCA2, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2, variants were first classified according to the databases generated by Vallée et al.28, and the InSIGHT consortium29, accessed through the LOVD websites (http://chromium.liacs.nl/LOVD2/colon_cancer/home.php? and http://brca.iarc.fr/LOVD/home.php?; accessed 1 February 2014, respectively). These groups have classified large numbers of variants in BRCA1, BRCA2, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2 according to the International Agency for Research on Cancer system based on available information from the literature. Classes 1 and 2 were considered benign; class 3 VUS; and classes 4 and 5 pathogenic. Rare nonsynonymous variants not in these databases were classified based on their predicted effect on the protein product. Nonsense and no-stop variants, variants changing the canonical splice sites (i.e. +/-2 base pairs), and frameshift insertions and deletions were considered pathogenic unless they occurred in the last exon. The remaining rare nonsynonymous variants were classified as VUS. Classification of each pathogenic variant was assessed based on a literature review performed independently by a clinical geneticist (J.L.E.). Variants classified as pathogenic mutations that were detected in the NGS data were inspected using the Integrative Genomics Viewer30, and variants that appeared to be true calls were verified with Sanger sequencing as previously described31. For MMR mutation carriers, immunohistochemistry was performed on available pancreatic tumors by our clinical lab for the MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2 proteins as previously described32.

Statistical analysis

The percentage of mutation carriers in the OPCS and the associated 95% confidence intervals were estimated from the random sample by an inverse-weighting strategy using the Horvitz-Thompson estimator with a finite population correction33. To assess the association between clinical characteristics and mutation prevalence, the sample was divided into subpopulations based on history of pancreatic, breast, and colorectal cancer in the proband or first-degree relative, as well as age at diagnosis (younger than 65 versus 65 and older, the sample median) and stage at diagnosis (Stage 2A or less versus Stage 2B and greater). Mutation prevalence estimates in these subpopulations were computed from the Horvitz-Thompson estimator incorporating sample weights and compared using Rao and Scott's Pearson chi-squared statistic33. Statistical significance level was set at p<0.05. Statistical analysis was performed in the R Environment for Statistical Computing (http://www.r-project.org/) using the “survey” package34.

Results

Patient selection and clinical characteristics

Seventy-one patients were randomly selected from 136 OPCS patients with a family history of PC, 39 from 85 patients with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer but no family history of PC, and 180 from 487 OPCS patients without family history of pancreatic, breast or ovarian cancer. Patient characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of pancreatic cancer probands, compared to the overall population-based study from which they were sampled.

| Clinical values | Sequenced sample of probands (%) (N=290) | Ontario Pancreas Cancer Study weighted % estimate (N=708) a |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 144/290 (49.7) | 49.1 (2.3) |

| Ashkenazi Jewish ethnicity | 13/290 (4.5) | 4.2 (0.9) |

| Cigarette smoking | ||

| Never | 133/280 (47.5) | 46.6 (2.3) |

| Former | 17/280 (6.1) | 6.01(1.1) |

| Current | 131/280 (46.8) | 47.4 (2.3) |

| Cancer in first-degree relative | ||

| Pancreas | 39/290 (13.9) | 10.5 (0.8) |

| Breast | 57/290 (19.7) | 18.5 (1.6) |

| Colorectal | 36/290 (12.4) | 12.2 (1.5) |

| Personal history of cancer | ||

| Breast | 6/290 (2.1) | 1.9 (0.6) |

| Colorectal | 7/290 (2.4) | 2.4 (0.7) |

| Age at pancreas cancer diagnosis | 64.5 (0.6)b | 64.3 (0.5)b |

| Stage 2A or less at diagnosis | 50/285 (17.5) | 17.4 (1.8) |

Estimates of the percentage (standard error) of each baseline characteristics reflective of all probands in the Ontario Pancreas Cancer Study estimated from the sequenced sample.

Mean (standard error).

Variant detection and characterization

The average number of sequencing reads per patient was 20,763,412 (range 6,438,944-75,459,926), of which on average 66% (range 35-88%) were unique reads that aligned to the target. The average depth of unique aligned reads covering each base within the target was 354 (range: 65 to 1328). On average, 10 and 50 unique sequencing reads covered 98% (range:91-99) and 95% (range:75-98) of the target in each sample, respectively.

Twenty-one mutations detected by NGS were predicted to be pathogenic (Supplementary Table 1). Of these, one appeared to be a false call based on very low variant allele fraction in the NGS data. Another 8 variants were false calls based on Sanger sequencing. Sanger sequencing primers could not be designed to verify a splice site single-nucleotide substitution in PRSS1 (c.40+1G>A) called in one sample. This patient had no history of pancreatitis. Therefore, eleven pathogenic variants were successfully verified with Sanger sequencing (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of the pancreatic cancer probands who carried pathogenic mutations in the sample of 290 probands who were sequenced for thirteen genes associated with pancreatic cancer risk.

| Gene | Reference sequence | Nucleotide | Codon | Previous cancer | Cancer in first-degree relatives | Immunohistochemistry | Age of onset | Stage at diagnosis | Survival from diagnosis (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATM | NM_000051 | c. 1931C>A | p.S644X | None | 1 pancreatic (non-carrier), 1 prostate, and 1 lymphoma | . | 66 | 2A | 7, alive |

| ATM | NM_000051 | c.3801delG | p.E1267fs | None | 1 breast and 1 prostate | . | 50 | 4 | 6, deceased |

| ATM | NM_000051 | c.8874_8877del | p.2958_2959del | None | 1 lung and 1 prostate | . | 58 | 4 | 18, deceased |

| BRCA1 | NM_007294 | c.4117G>T | p.E1373X | None | 1 lung | . | 59 | 1B | 2, alive |

| BRCA2 | NM_000059 | c.2806_2809del | p.936_937del | None | 1 breast, 2 multiple myeloma | . | 62 | 4 | 6, deceased |

| BRCA2 | NM_000059 | c.5066_5067insA | p.A1689fs | None | 1 colorectal and 1 kidney | . | 67 | 2B | 82, alive |

| MLH1 | NM_000249 | c.677+3A>G | . | CRC age 62 | 2 breast, 1 lymphoma | N/A | 66 | 2B | 10, deceased |

| MSH2 | NM_000251 | c.942+3A>T | . | None | 2 colorectal, 1 breast, 1 ureter, 1 bladder, 1 kidney | Deficient | 68 | 2B | 13, alive |

| MSH2 | NM_000251 | c.1906g>c | p.A636P | CRC at age 24 and 43 | 1 breast, 1 colorectal | Deficient | 53 | 3 | 19, deceased |

| MSH6 | NM_000179 | c.1707delC | p.F569fs | Gallbladder, CRC and lung at age 69 | 1 breast, 1 colorectal, 1 melanoma, 1 endometrial, 1 prostate | N/A | 71 | 2B | 7, deceased |

| TP53 | NM_000546 | c.916C>T | p.R306X | None | None | . | 65 | 4 | 13, deceased |

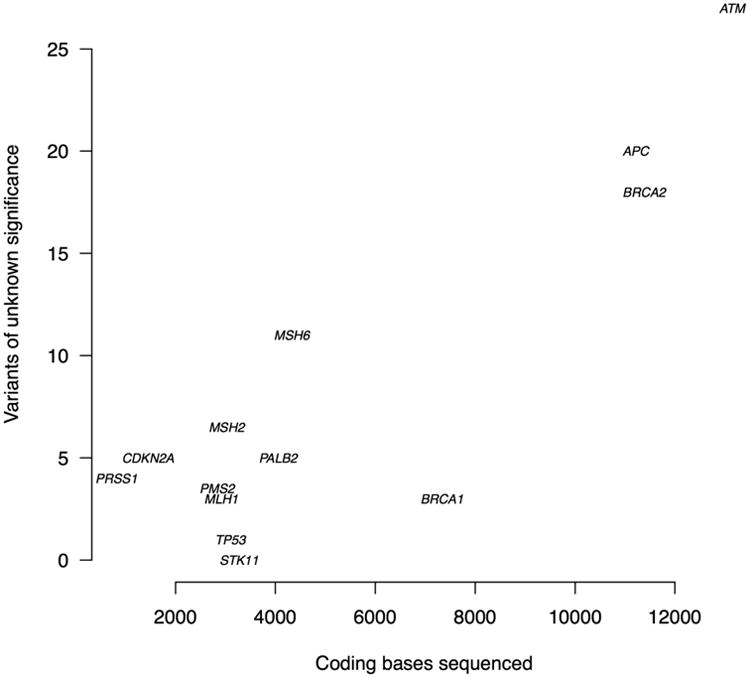

There were 144 other rare nonsynonymous variants detected in the 13 genes that were not deemed pathogenic. Of these, 37 were benign according to the IARC databases. One of the remaining 107 VUS was a frameshift deletion in the last exon of BRCA2 (c.2806_2809del) that introduces a stop codon 172 bases from the reference stop codon. On average, each proband carried 1.2 VUS (range 0-6). The number of VUS identified per gene was strongly correlated with the number of bases sequenced per gene (correlation coefficient=0.88; p<0.001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The number of variants of unknown significance detected in each gene versus bases sequenced of each gene (correlation coefficient=0.88; p<0.001).

Pathogenic mutation carriers

Eleven of the 290 probands carried a pathogenic mutation (Table 2), which corresponded to a 3.8% (95% confidence interval: 2.1-5.6%) mutation carrier prevalence in the OPCS (Figure 2). Three mutations were in ATM, one in BRCA1, two in BRCA2, one in MLH1, two in MSH2, one in MSH6, and one in TP53. The youngest age of onset for PC in all patients carrying mutations was 50 years. While most patients carrying mutations had some family history of cancer, none met the Amsterdam II criteria for Lynch Syndrome8. Only one patient had a first-degree relative with PC. This relative did not carry the same ATM mutation as the proband, as described in a previous report31. Two other probands had relatives with DNA available to determine whether the mutations were transmitted or were de novo. A sister of the MSH2 c.942+3A>T carrier also carried the mutation. She had a history of colon cancer, ductal breast cancer, bladder and transitional cell carcinoma of the ureter, and sebaceous carcinoma. A niece of the MSH6 p.F569fs carrier also carried the mutation. Her father (the proband's brother) died of colorectal cancer. The two MMR mutation carriers with pancreatic tumor specimens available for MMR immunohistochemistry were immunodeficient for the respective protein encoded by the gene with the germline mutation. There was no family or personal cancer history in the TP53 nonsense carrier, who developed PC at age 65. No other biospecimens were available from the probands or relatives for segregation or tumor analysis.

Figure 2.

The prevalence of germline mutations in thirteen genes sequenced in a population-based cohort of pancreatic cancer patients (N=708), estimated from a random sample (N=290), with genes grouped by the predominantly associated cancer. The squares reflect point estimates, the bands reflect 95% confidence intervals, and the diamonds reflect summary estimates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

Clinical characteristics and mutation carrier status

There was a significant association between mutation carrier status and the following: breast cancer in the proband or a first-degree relative (10.7% (4.4-17.0) versus 2.1% (0.7-3.6), p<0.001), and colorectal cancer in the proband or a first-degree relative (11.1% (3.0-19.1) versus 2.8% (1.2-4.3), p=0.002) (Figure 3). There was no significant association between mutation carrier status and first-degree relatives with PC, age at diagnosis, or stage at diagnosis.

Figure 3.

The prevalence of germline mutations in thirteen genes sequenced in a population-based cohort of pancreatic cancer patients (N=708), estimated from a random sample (N=290), with the cohort subdivided by the presence of pancreatic cancer in a first-degree relative, and the presence of breast or colorectal cancer in the proband or a first-degree relative. The squares reflect point estimates, the bands reflect 95% confidence intervals, and the diamonds reflect summary estimates and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

In our study, thirteen genes that substantially increase risk of PC were sequenced using a multiple-gene panel in 290 patients sampled from a population-based cohort of pathologically confirmed PC patients. Eleven germline mutations in seven genes were identified, the majority in genes associated with inherited breast and colorectal cancer. The mutation carrier prevalence was 3.8% (2.1-5.6%), corresponding to approximately 1 in 26 probands. The mutation carrier prevalence approached 1 in 10 when the proband or a first-degree relative had a history of breast or colorectal cancer. Family history of PC, age of diagnosis, and stage were not associated with mutations in the genes sequenced.

The mutations detected in this study have clinical implications for the probands and their relatives who carry the mutation. BRCA mutation carriers may benefit from tamoxifen and prophylactic mastectomy and/or salpingo-opherectomy for primary prevention, and more rigorous breast cancer surveillance for secondary prevention18, 19, 35, 36. Carriers of MMR mutations may benefit from daily aspirin as a preventative measure, prophylactic hysterectomies, and earlier and more frequent colonoscopies37. The clinical implications of the mutations discovered in ATM are less clear, although some experts would recommend augmented breast cancer surveillance38. Furthermore, all mutation carriers represent a high-risk subgroup of patients for PC researchers to consider for screening studies and for experimental targeted therapies.

Previous studies that have sequenced genes known to increase risk of PC have focused on high-risk subsets of PC patients, for example, based on ethnicity or family history of cancer39-53. Estimates of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation prevalence in select subgroups of PC patients based on Ashkenazi Jewish ethnicity or family history of breast, ovarian and/or PC ranged from 0 to 24% 40, 41, 43-46, 49, 50, 52, 53. Only two small studies have sequenced MMR genes in cohorts of PC patients selected for ethnicity or family history51,47. The rate of MMR gene mutations in our cohort, comparable to that in colorectal cancer cohorts, warrants further investigation. Our cohort had no PALB2 or CDK2NA mutation carriers, which is consistent with previous studies that found very low rates of PALB2 and CDKN2A mutations in PC 12, 39, 49, 50, 54-56. The lack of mutations in APC, PRSS1, and STK11 does not eliminate the possibility that these genes cause a small proportion of PC.

Our study has several limitations. First, our approach to classifying variants was conservative; many rare nonsynonymous variants were classified as VUS. If some VUS are pathogenic, we may have underestimated the prevalence of mutation carriers. There was a significant correlation between the number of VUS and bases sequenced per gene, which supports a more benign role for most of these variants. Second, we only assessed single nucleotide substitutions and small insertions and deletions, not other potential sources of pathogenic genetic variation, which would again lead to conservative estimates of mutation carrier prevalence. Finally, there are important limitations to the OPCS as a population-based registry. Given the poor prognosis of PC, it is difficult to recruit PC patients using traditional epidemiologic strategies, including rapid case ascertainment afforded by our Ontario Cancer Registry57. During the study period, the OPCS recruited from all of Ontario based on pathological diagnosis of PC, which ensures no contamination with patients with other diagnoses. Unfortunately, this neglects patients with advanced disease who never receive a pathological diagnosis. Among patients with a pathological diagnosis, the OPCS has a response rate around 25%21. Participants tend to be younger, surgical patients treated in academic centers21. If the factors affecting inclusion in the OPCS are related to mutation carrier status, our results may not accurately reflect the population of Ontario. We did not find age or stage to be associated with carrier status; future adequately powered studies should explore these potential associations.

Technologic advances have made the cost of multiple-gene panels comparable to individual gene testing58; however, the added value of simultaneously sequencing many genes remains uncertain59 and likely depends on the clinical setting. Multiple gene panels have been evaluated in breast and ovarian cancer cohorts60-62, leading to the recent development of guidelines that recommend multiple-gene panels for breast cancer patients when family history is consistent with mutations in a range of genes63. We detected a wide breadth of mutations in our cohort of PC patients. This supports the use of multiple gene panels in PC, and emphasizes the importance of ongoing efforts to catalogue and characterize variants in genes that predispose to PC28, 29 and to identify new genes that cause PC. Interestingly, probands with personal or family history of breast or colorectal cancer were most likely to carry mutations, but classic personal and family history was absent in several cases. This raises questions with important clinical implications. With falling sequencing costs, which patients should be referred for multiple-gene panel sequencing? What is the relevance of mutations in probands with atypical personal and family history? Studies suggest that familial factors modify tissue-specific cancers risks for germline mutations in the BRCA and MMR genes64-66. Do mutations in pancreatic cancer probands with atypical family history impart a different cancer risk? Addressing these questions will require innovative approaches and extensive genetic characterization of large cohorts. Ongoing collaborative international sequencing efforts of well-characterized PC patients67, 68 form the foundation to answer these challenging questions.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary table 1: Rare nonsynonymous variants in genes that predispose to pancreatic cancer in 290 probands from the Ontario Pancreatic Cancer Study. InSIGHT refers to the classification by the InSIGHT consortium (PubMed ID: 24362816) and Vallee to the IARC classification of Vallee et al. (21990165). The variant annotation (SIFT, polyphen, etc.) comes from the LJB database from the ANNOVAR program (http://www.openbioinformatics.org/annovar/annovar_filter.html#ljb23).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Weston Garfield Foundation, Pancreatic Cancer Canada, National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health (R01CA97075), the Mount Sinai Hospital Biospecimen Repository, Teresa Bianco, and the patients who participated in this study for supporting this research.

Abbreviations

- MMR

mismatch repair

- NGS

next-generation sequencing

- OPCS

Ontario Pancreas Cancer Study

- PC

pancreatic cancer

- VUS

variants of unknown significance

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

Author contributions: Study concept and design: R.C.G., L.B., J.L.E., S.H., S.G.

Acquisition of data: R.C.G., I.S., A.A.C., S.S., A.B., L.B., G.M.P., J.L.E., S.H., S.G.

Analysis and interpretation of data: R.C.G., I.S., A.A.C., S.S., A.B., L.B., G.M.P., J.L.E., S.H., S.G.

Drafting of the manuscript: R.C.G., S.G.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: R.C.G., I.S., A.A.C., S.S., A.B., L.B., G.M.P., J.L.E., S.H., S.G.

Obtained funding: G.M.P., J.L.E., S.G.

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authors

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kanji ZS, Gallinger S. Diagnosis and management of pancreatic cancer. CMAJ. 2013;185:1219–26. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tempero MA, Arnoletti JP, Behrman SW, et al. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma, version 2.2012: featured updates to the NCCN Guidelines. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network: JNCCN. 2012;10:703–13. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, et al. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Risch HA, McLaughlin JR, Cole DE, et al. Population BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation frequencies and cancer penetrances: a kin-cohort study in Ontario, Canada. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2006;98:1694–706. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moran A, O'Hara C, Khan S, et al. Risk of cancer other than breast or ovarian in individuals with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Familial cancer. 2012;11:235–42. doi: 10.1007/s10689-011-9506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Asperen CJ, Brohet RM, Meijers-Heijboer EJ, et al. Cancer risks in BRCA2 families: estimates for sites other than breast and ovary. Journal of medical genetics. 2005;42:711–9. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.028829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin KM, Shashidharan M, Thorson AG, et al. Cumulative incidence of colorectal and extracolonic cancers in MLH1 and MSH2 mutation carriers of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery: official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 1998;2:67–71. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(98)80105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Umar A, Boland CR, Terdiman JP, et al. Revised Bethesda Guidelines for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) and microsatellite instability. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2004;96:261–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Win AK, Lindor NM, Young JP, et al. Risks of primary extracolonic cancers following colorectal cancer in lynch syndrome. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2012;104:1363–72. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kastrinos F, Mukherjee B, Tayob N, et al. Risk of pancreatic cancer in families with Lynch syndrome. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;302:1790–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruijs MW, Verhoef S, Rookus MA, et al. TP53 germline mutation testing in 180 families suspected of Li-Fraumeni syndrome: mutation detection rate and relative frequency of cancers in different familial phenotypes. Journal of medical genetics. 2010;47:421–8. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.073429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones S, Hruban RH, Kamiyama M, et al. Exomic sequencing identifies PALB2 as a pancreatic cancer susceptibility gene. Science. 2009;324:217. doi: 10.1126/science.1171202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts NJ, Jiao Y, Yu J, et al. ATM mutations in patients with hereditary pancreatic cancer. Cancer discovery. 2012;2:41–6. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fogelman DR, Wolff RA, Kopetz S, et al. Evidence for the efficacy of Iniparib, a PARP-1 inhibitor, in BRCA2-associated pancreatic cancer. Anticancer research. 2011;31:1417–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tran B, Moore S, Zogopoulos G, et al. Platinum-based chemotherapy in pancreatic adenocarcinoma associated with BRCA mutations: A translational case series. Journal of clinical oncology. 2012;30 Abstract 217. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Sukhni W, Borgida A, Rothenmund H, et al. Screening for pancreatic cancer in a high-risk cohort: an eight-year experience. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery. 2012;16:771–83. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1781-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sud A, Wham D, Catalano M, et al. Promising outcomes of screening for pancreatic cancer by genetic testing and endoscopic ultrasound. Pancreas. 2014;43:458–61. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berek JS, Chalas E, Edelson M, et al. Prophylactic and risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy: recommendations based on risk of ovarian cancer. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2010;116:733–43. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ec5fc1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Schaid DJ, et al. Efficacy of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutation carriers. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2001;93:1633–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.21.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Sukhni W, Aronson M, Gallinger S. Hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes: familial adenomatous polyposis and lynch syndrome. The Surgical clinics of North America. 2008;88:819–44. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borgida AE, Ashamalla S, Al-Sukhni W, et al. Management of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in Ontario, Canada: a population-based study using novel case ascertainment. Canadian journal of surgery. 2011;54:54–60. doi: 10.1503/cjs.026409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi Y, Briollais L. An EM composite likelihood approach for multistage sampling of family data. Statistica Sinica. 2011;21:231–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:589–95. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome research. 2010;20:1297–303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, et al. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherry ST, Ward MH, Kholodov M, et al. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic acids research. 2001;29:308–11. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vallee MP, Francy TC, Judkins MK, et al. Classification of missense substitutions in the BRCA genes: a database dedicated to Ex-UVs. Human mutation. 2012;33:22–8. doi: 10.1002/humu.21629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.InSIGHT. Application of a 5-tiered scheme for standardized classification of 2,360 unique mismatch repair gene variants in the InSiGHT locus-specific database. Nature genetics. 2014;46:107–15. doi: 10.1038/ng.2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thorvaldsdottir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Briefings in bioinformatics. 2013;14:178–92. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grant RC, Al-Sukhni W, Borgida AE, et al. Exome sequencing identifies nonsegregating nonsense ATM and PALB2 variants in familial pancreatic cancer. Human genomics. 2013;7:11. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-7-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bacani J, Zwingerman R, Di Nicola N, et al. Tumor microsatellite instability in early onset gastric cancer. The Journal of molecular diagnostics: JMD. 2005;7:465–77. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60577-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lumley T. Complex surveys: a guide to analysis using R. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lumley T. Analysis of Complex Survey Samples. Journal of Statistical Software. 2004;9:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lowry KP, Lee JM, Kong CY, et al. Annual screening strategies in BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutation carriers: a comparative effectiveness analysis. Cancer. 2012;118:2021–30. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duffy SW, Nixon RM. Estimates of the likely prophylactic effect of tamoxifen in women with high risk BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. British journal of cancer. 2002;86:218–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vasen HF, Blanco I, Aktan-Collan K, et al. Revised guidelines for the clinical management of Lynch syndrome (HNPCC): recommendations by a group of European experts. Gut. 2013;62:812–23. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.NHS Cancer Screening Programs. Protocols for the surveillance of women at higher risk of developing breast cancer, Version 4. 2013;74 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tischkowitz MD, Sabbaghian N, Hamel N, et al. Analysis of the gene coding for the BRCA2-interacting protein PALB2 in familial and sporadic pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1183–6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stadler ZK, Salo-Mullen E, Patil SM, et al. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Ashkenazi Jewish families with breast and pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:493–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slater EP, Langer P, Fendrich V, et al. Prevalence of BRCA2 and CDKN2a mutations in German familial pancreatic cancer families. Familial cancer. 2010;9:335–43. doi: 10.1007/s10689-010-9329-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ozcelik H, Schmocker B, Di Nicola N, et al. Germline BRCA2 6174delT mutations in Ashkenazi Jewish pancreatic cancer patients. Nature genetics. 1997;16:17–8. doi: 10.1038/ng0597-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murphy KM, Brune KA, Griffin C, et al. Evaluation of candidate genes MAP2K4, MADH4, ACVR1B, and BRCA2 in familial pancreatic cancer: deleterious BRCA2 mutations in 17% Cancer research. 2002;62:3789–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lucas AL, Shakya R, Lipsyc MD, et al. High prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations with loss of heterozygosity in a series of resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma and other neoplastic lesions. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2013;19:3396–403. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lawniczak M, Gawin A, Bialek A, et al. Is there any relationship between BRCA1 gene mutation and pancreatic cancer development? Polskie Archiwum Medycyny Wewnetrznej. 2008;118:645–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lal G, Liu G, Schmocker B, et al. Inherited predisposition to pancreatic adenocarcinoma: role of family history and germ-line p16, BRCA1, and BRCA2 mutations. Cancer research. 2000;60:409–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laitman Y, Herskovitz L, Golan T, et al. The founder Ashkenazi Jewish mutations in the MSH2 and MSH6 genes in Israeli patients with gastric and pancreatic cancer. Familial cancer. 2012;11:243–7. doi: 10.1007/s10689-011-9507-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goggins M, Schutte M, Lu J, et al. Germline BRCA2 gene mutations in patients with apparently sporadic pancreatic carcinomas. Cancer research. 1996;56:5360–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ghiorzo P, Pensotti V, Fornarini G, et al. Contribution of germline mutations in the BRCA and PALB2 genes to pancreatic cancer in Italy. Familial cancer. 2012;11:41–7. doi: 10.1007/s10689-011-9483-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ghiorzo P, Fornarini G, Sciallero S, et al. CDKN2A is the main susceptibility gene in Italian pancreatic cancer families. Journal of medical genetics. 2012;49:164–70. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gargiulo S, Torrini M, Ollila S, et al. Germline MLH1 and MSH2 mutations in Italian pancreatic cancer patients with suspected Lynch syndrome. Familial cancer. 2009;8:547–53. doi: 10.1007/s10689-009-9285-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Couch FJ, Johnson MR, Rabe KG, et al. The prevalence of BRCA2 mutations in familial pancreatic cancer. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2007;16:342–6. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Axilbund JE, Argani P, Kamiyama M, et al. Absence of germline BRCA1 mutations in familial pancreatic cancer patients. Cancer biology & therapy. 2009;8:131–5. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.2.7136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blanco A, de la Hoya M, Osorio A, et al. Analysis of PALB2 gene in BRCA1/BRCA2 negative Spanish hereditary breast/ovarian cancer families with pancreatic cancer cases. PloS one. 2013;8:e67538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harinck F, Kluijt I, van Mil SE, et al. Routine testing for PALB2 mutations in familial pancreatic cancer families and breast cancer families with pancreatic cancer is not indicated. European journal of human genetics: EJHG. 2012;20:577–9. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang XR, Jessop L, Myers T, et al. Lack of germline PALB2 mutations in melanoma-prone families with CDKN2A mutations and pancreatic cancer. Familial cancer. 2011;10:545–8. doi: 10.1007/s10689-011-9447-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.El-Rayes BF, Jasti P, Severson RK, et al. Impact of race, age, and socioeconomic status on participation in pancreatic cancer clinical trials. Pancreas. 2010;39:967–71. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181da91dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kurian AW, Hare EE, Mills MA, et al. Clinical evaluation of a multiple-gene sequencing panel for hereditary cancer risk assessment. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32:2001–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.6607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Domchek SM, Bradbury A, Garber JE, et al. Multiplex genetic testing for cancer susceptibility: out on the high wire without a net? Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:1267–70. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.9403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kurian AW, Hare EE, Mills MA, et al. Clinical evaluation of a multiple-gene sequencing panel for hereditary cancer risk assessment. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2001–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.6607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Walsh T, Casadei S, Lee MK, et al. Mutations in 12 genes for inherited ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal carcinoma identified by massively parallel sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:18032–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115052108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tung N, Battelli C, Allen B, et al. Frequency of mutations in individuals with breast cancer referred for BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing using next-generation sequencing with a 25-gene panel. Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1002/cncr.29010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Daly MB, Pilarski R, Axilbund JE, et al. Genetic/Familial high-risk assessment: breast and ovarian, version 1.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:1326–38. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Simchoni S, Friedman E, Kaufman B, et al. Familial clustering of site-specific cancer risks associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in the Ashkenazi Jewish population. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3770–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511301103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Antoniou A, Pharoah PD, Narod S, et al. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case Series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1117–30. doi: 10.1086/375033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dowty JG, Win AK, Buchanan DD, et al. Cancer risks for MLH1 and MSH2 mutation carriers. Hum Mutat. 2013;34:490–7. doi: 10.1002/humu.22262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Biankin AV, Waddell N, Kassahn KS, et al. Pancreatic cancer genomes reveal aberrations in axon guidance pathway genes. Nature. 2012;491:399–405. doi: 10.1038/nature11547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Petersen GM, de Andrade M, Goggins M, et al. Pancreatic cancer genetic epidemiology consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:704–10. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary table 1: Rare nonsynonymous variants in genes that predispose to pancreatic cancer in 290 probands from the Ontario Pancreatic Cancer Study. InSIGHT refers to the classification by the InSIGHT consortium (PubMed ID: 24362816) and Vallee to the IARC classification of Vallee et al. (21990165). The variant annotation (SIFT, polyphen, etc.) comes from the LJB database from the ANNOVAR program (http://www.openbioinformatics.org/annovar/annovar_filter.html#ljb23).