Abstract

The optoelectronic nature of two-dimensional sheets of sp2-hydridized carbons (for example, graphenes and nanographenes) can be dramatically altered and tuned by altering the degree of π-extension, shape, width and edge topology. Among various approaches to synthesize nanographenes with atom-by-atom precision, one-shot annulative π-extension (APEX) reactions of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons hold significant potential not only to achieve a ‘growth from template’ synthesis of nanographenes, but also to fine-tune the properties of nanographenes. Here we describe one-shot APEX reactions that occur at the K-region (convex armchair edge) of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by the Pd(CH3CN)4(SbF6)2/o-chloranil catalytic system with silicon-bridged aromatics as π-extending agents. Density functional theory calculations suggest that the complete K-region selectivity stems from the olefinic (decreased aromatic) character of the K-region. The protocol is applicable to multiple APEX and sequential APEX reactions, to construct various nanographene structures in a rapid and programmable manner.

Bottom-up synthesis of nanographenes is highly desirable. Here, the authors report one-shot annulative π-extension reactions that occur at the convex armchair edge of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and show that unfunctionalized precursors can be used for π-component assembly and extension.

Bottom-up synthesis of nanographenes is highly desirable. Here, the authors report one-shot annulative π-extension reactions that occur at the convex armchair edge of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and show that unfunctionalized precursors can be used for π-component assembly and extension.

Nanographenes, which are nanometre-size subunits of graphenes (single-layer two-dimensional sp2-hybridized carbon sheets)1,2,3,4,5 with a tunable bandgap, have become hot molecular entities in the field of nanocarbon materials science6. As the properties of nanographenes depend heavily on the degree of π-extension, shape, width and edge topology, a novel bottom-up methodology for the precisely controlled synthesis of structurally uniform nanographenes is highly desirable6. Among various approaches to synthesize nanographenes with atom-by-atom precision6, one-shot annulative π-extension (APEX) reactions of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) hold significant potential not only to achieve a ‘growth from template’ synthesis of nanographenes, but also to fine-tune the properties of nanographenes.

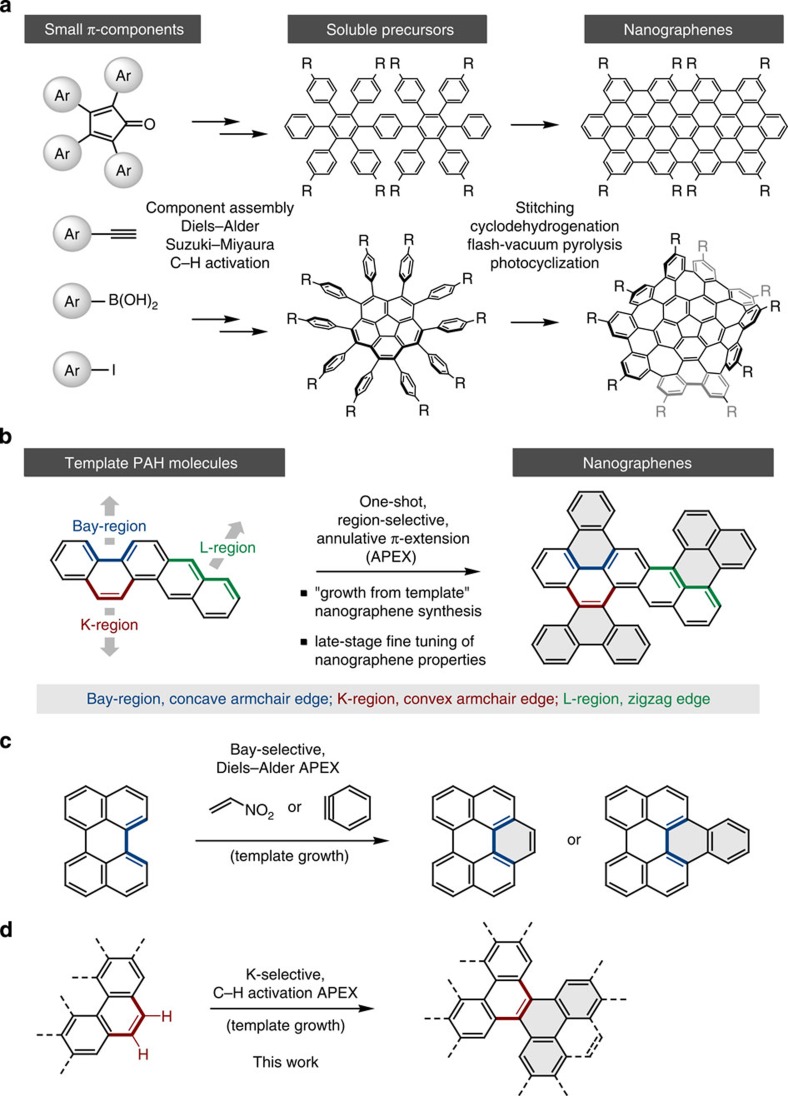

In the last two decades, various bottom-up organic synthesis methods have been established for the controlled synthesis of large π-extended PAHs and nanographenes, as exemplified by the groundbreaking achievements of Müllen and colleagues7,8,9,10, Scott and colleagues11,12, Fasel and colleagues13,14 and others15 (Fig. 1a). In essence, most of the reported nanographene syntheses rely on a two-step sequence of (i) component assembly of small π-components, using reactions such as Diels–Alder reactions, Suzuki–Miyaura couplings and C–H activation reactions, to synthesize soluble nanographene precursors, followed by (ii) stitching (graphenization6) of soluble polyphenylene precursors by cyclodehydrogenation, flash-vacuum pyrolysis or photocyclization, to yield the target nanographenes (Fig. 1a)6,16. Although this state-of-the-art methodology has contributed significantly to the rapid progress of nanographene materials science, it has been well documented that the final and vital step of stitching (graphenization) is usually problematic16. For example, intramolecular oxidative cyclodehydrogenation by Lewis acids and oxidants (Scholl-type reactions) often suffer from problems such as incomplete stitching, lack of regioselectivity and undesirable rearrangements.

Figure 1. Organic synthesis approaches for structurally uniform nanographenes.

(a) The well-established two-step synthesis of nanographenes through π-component-assembling reaction and stitching (graphenization). (b) One-shot, region-selective APEX as alternative synthesis and functionalization of nanographenes through ‘growth from template’. (c) One-shot, bay-region-selective APEX by Diels–Alder reaction. (d) One-shot, K-region-selective APEX by double C–H activation (this work).

The continuing evolution of nanographene science is heavily dependent on the discovery of new reactions and strategies that allow rapid and predictable synthesis, and functionalization of nanographenes. Here we illustrate the significant potential of one-shot APEX reactions of template PAH molecules with π-extending agents (Fig. 1b) as an enabling concept that is complementary to the aforementioned two-step methodology. By devising APEX reactions that are selective to the specific regions of PAH structures (bay region, K-region and L-region, see Fig. 1b)17, the direction-controlled growth or polymerization of a template PAH producing structurally uniform nanographenes would become possible. These regions correspond to the concave armchair edge (bay region), convex armchair edge (K-region) and zigzag edge (L-region) in graphene nomenclature. APEX technology should also be useful for the late-stage fine-tuning of nanographene properties by subtly modifying their edge structures. Moreover, as a result of significant recent progress in surface-catalysed cyclodehydrogenation and subsequent epitaxial elongation reactions of PAHs by the group of Fasel and colleagues18, a number of π-extended PAHs provided by the APEX technology could also be converted into structurally uniform carbon nanotubes18,19.

Although the full potential of APEX reactions in nanographene chemistry is yet to be realized partly because the concept had not been formulated, significant experimental20,21,22,23,24,25 and theoretical26 advances have appeared, describing methods for bay-region-specific π-extension in PAHs. For example, Scott has revisited the finding of the Diels–Alder reactivity at the PAH bay regions by Clar et al.27 and proposed its use for metal-free growth of single-chirality carbon nanotubes20,21,22,23,24,25,26 (Fig. 1c). This represents a bay-region-selective APEX reaction in our definition. However, no APEX reactions at other PAH regions (L-region and K-region) have been developed up until now. Although the dimerization of perylene under Scholl-type coupling to furnish quaterrylene represents the closest example of an L-region-selective APEX reaction, this can be categorized as the two-step method having a serious problem at the stitching (cyclodehydrogenation) stage28. The reactions at K-regions (convex armchair edges) are considered to be particularly difficult, as K-region bonds tend to have relatively high bond orders, and most aromatic substitution reactions occur preferentially at other aromatic C–H bonds17.

Our APEX campaign29,30,31,32,33,34 began when we serendipitously discovered Pd(OAc)2/o-chloranil as the first-generation C–H activation catalyst for PAHs in 2011 (ref. 35). This catalyst uniquely and effectively promotes the C–H arylation of non-functionalized PAHs with arylboroxines, with complete K-region selectivity. When coupled with the Scholl-type cyclodehydrogenation of the thus-formed arylated PAHs, a number of structurally intriguing nanographenes such as warped nanographenes34 (Fig. 1a) have been synthesized. Although this was a two-step nanographene synthesis at the time, we felt that the observed C–H activation reactivity and selectivity might be translated into an APEX reaction when the K-region is activated and annulated with properly arranged 1,4-dimetal π-units in a [2+4] annulation manner. Here, in we describe a one-shot APEX reaction that occurs selectively at the K-region of PAHs via double C–H activation36,37,38,39 (Fig. 1d). This protocol is applicable to multiple APEX and sequential APEX reactions to construct various nanographene structures in a rapid and programmable manner.

Results

Development of catalyst

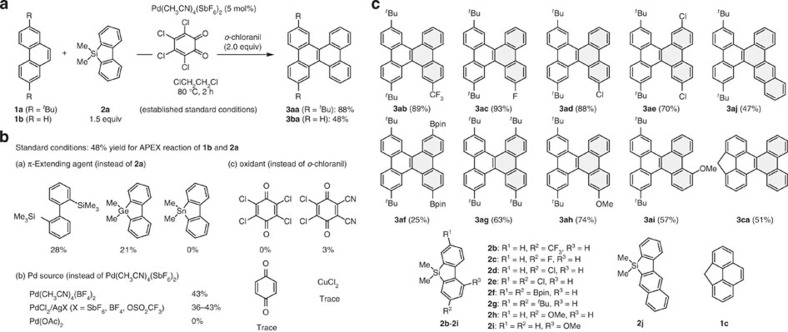

We began our study by examining various palladium salts, ligands, oxidants and π-extending agents for the APEX reaction of phenanthrenes 1a and 1b. After extensive screening, we determined that Pd(CH3CN)4(SbF6)2 and o-chloranil serve as an efficient pre-catalyst and oxidant respectively, while silicon-bridged aromatics 2 are optimal π-extending agents (Fig. 2a). For example, when 2,7-di-tert-butyl-phenanthrene (1a: 1.0 equiv) was treated with dimethyldibenzosilole40 (2a: 1.5 equiv) in 1,2-dichloroethane at 80 °C for 2 h in the presence of Pd(CH3CN)4(SbF6)2 (5 mol%) and o-chloranil (2.0 equiv), the corresponding K-region-annulated APEX product 3aa was obtained in 88% isolated yield, representing our standard APEX conditions. Unfunctionalized phenanthrene (1b) also underwent an APEX reaction with 2a to yield dibenzo[g,p]chrysene (3ba). It should be noted that under these conditions, we observed the annulation exclusively at the K-region of phenanthrene 1a or 1b.

Figure 2. One-shot K-region-selective C–H activation APEX.

(a) The established reaction conditions. (b) Deviation from standard conditions (effect of reaction parameters) in the reaction of 1b and 2a. (c) Scope of one-shot, K-region-selective, C–H activation APEX. Reaction conditions: polycyclic aromatic compounds 1 (0.2 mmol), silicon-bridged aromatics 2 (1.5 equiv), Pd(CH3CN)4(SbF6)2 (5 mol%), o-chloranil (2.0 equiv), 1,2-dichloroethane, 80 °C, 2 h. Bpin, pinacolatoboryl.

Listed in Fig. 2b are the effects of variations from the standard APEX conditions (1b+2a→3ba: 48% yield). For full lists of the effects of reaction parameters, see Supplementary Tables 2–4. As for the π-extension agents, we found that other dimetallobiphenyl derivatives such as 2,2′-bis(trimethylsilyl)-1,1′-biphenyl and dimethyldibenzogermole also reacted but led to the desired product in much lower yield. Dimethyldibenzostannole did not yield the product but generated a considerable amount of tetraphenylene and quaterphenyl by homodimerization. Changing the methyl groups of 2a only had detrimental effect on reaction efficiency. The commercially available cationic palladium complex Pd(CH3CN)4(BF4)2 showed APEX activity comparable to Pd(CH3CN)4(SbF6)2. Similar catalytic activities were also observed with the combined use of PdCl2 and silver salts such as AgOSO2CF3, AgBF4 and AgSbF6. On the other hand, neutral Pd(OAc)2 (our previous palladium pre-catalyst)29 did not promote the APEX reaction at all. These results clearly indicate the importance of a cationic palladium species for the APEX reaction to occur. In the investigation of oxidants, commonly used oxidants such as benzoquinone, p-chloranil, DDQ and CuCl2 (ref. 35) displayed virtually no APEX-type activity. We assume that the high reactivity of o-chloranil stems not only from its high oxidation aptitude but also from its unique o-quinone structure, which can bind to palladium in a bidentate manner and modulate the redox property effectively41,42. Our preferred solvent is 1,2-dichloroethane, but aromatic solvents such as toluene, chlorobenzene, 1,2-dichlorobenzene, fluorobenzene and trifluoromethylbenzene can also be used for the present APEX reactions.

Scope of K-region-selective APEX

As shown in Fig. 2c, various structurally and electronically diverse silicon-bridged aromatics 2 were found to react with 2,7-di-tert-butylphenanthrene (1a), providing the corresponding dibenzo[g,p]chrysenes (3ab–3aj) in good-to-excellent yield with virtually complete K-region selectivity. In particular, dibenzosiloles having electron-deficient substituents (2b–2e)40,43 showed excellent reactivity. The tribenzo[a,c,f]tetraphene framework (3aj) can be readily constructed by the APEX reaction of 1a and benzonaphthosilole 2j43. Notably, dichloro- and diboryl-substituted dibenzosiloles underwent the APEX reaction smoothly, leaving C–Cl and C–B bonds intact (3ad, 3ae and 3af). The tolerance of the reaction for these bonds makes it attractive for further π-extension and functionalization, using well-established cross-coupling chemistry. Furthermore, methylene-bridged phenanthrene 1c reacted with 2a to afford benzoindenochrysene 3ca, which can potentially lead to soluble nanographenes by facile substitution at the methylene moiety. Ease of post-functionalization is particularly advantageous for controlled surface alignment of nanographenes for device applications.

Mechanistic considerations of K-region-selective APEX

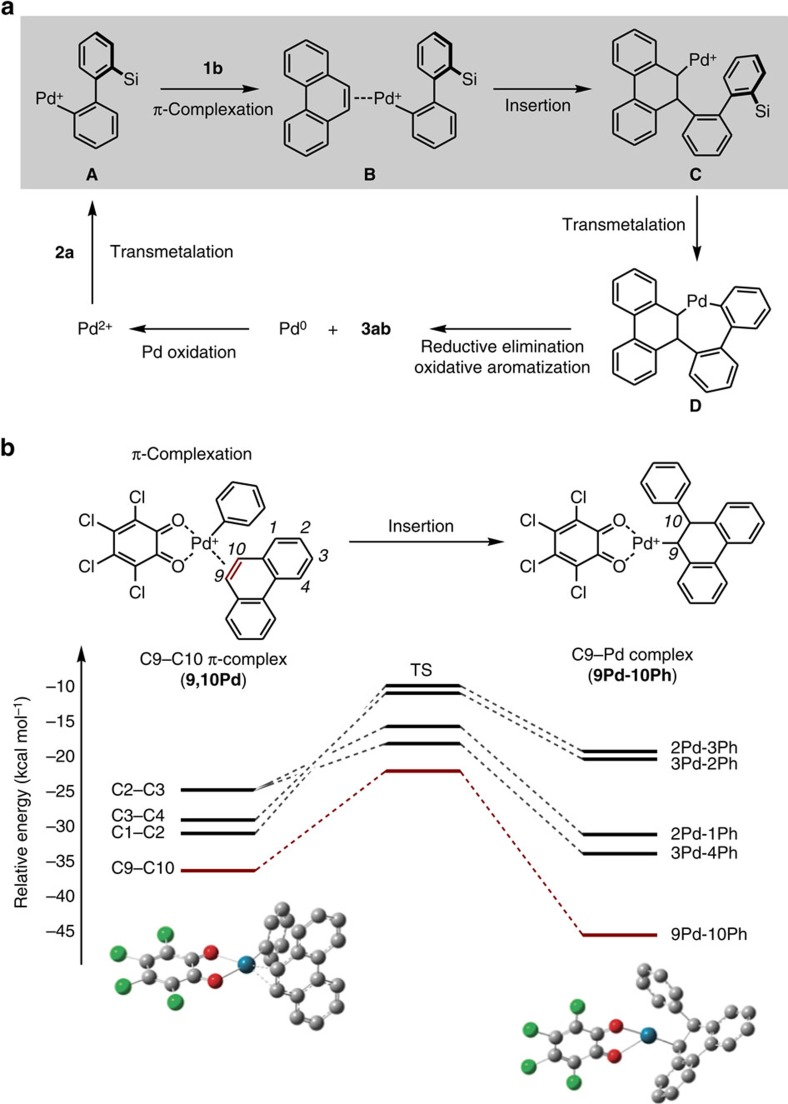

Although the exact mechanism of the present APEX reaction remains unclear, our current assumption is shown in Fig. 3a. A palladium(II) species undergoes the first transmetalation with silicon-bridged aromatic 2a, followed by coordination of phenanthrene (1b) to arylpalladium intermediate A at the K-region, yielding π-complex B. Coordination-induced insertion at the K-region C=C bond, followed by a second transmetalation forms palladacycle intermediate D. Reductive elimination and oxidative aromatization yields APEX product 3ab and palladium(0), the latter of which is oxidized to the active palladium(II) species by the action of o-chloranil.

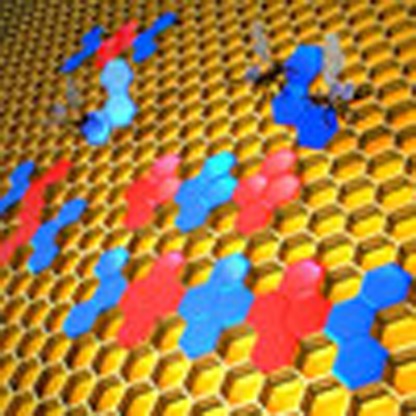

Figure 3. Mechanistic considerations.

(a) A possible mechanism of K-region-selective C–H activation APEX. (b) Theoretical calculations of π-complexation and insertion steps. Structures were optimized by the density functional theory (DFT44) calculations using B3PW91 hybrid functional45,46 (hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity). Reaction pathways were followed by intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC47,48) computations, and high-accuracy, single-point energy calculations of DFT-optimized structures were performed with Møller–Plesset perturbation theory (MP2) (ref. 49). Energies are relative to that of o-chloranil-bound cationic phenylpalladium species.

We assume that the K-region selectivity in the present APEX reaction stems from the preferential palladium π-complexation at the K-region of PAHs before the insertion step, as depicted in Fig. 3a. To prove this hypothesis, we conducted density functional theory44 calculations (using B3PW91 hybrid functional45,46) for the π-complexation and insertion steps on a model reaction of o-chloranil-bound cationic phenylpalladium species with phenanthrene yielding the alkylpalladium species shown in Fig. 3b (a model reaction relevant to A→B→C in Fig. 3a). Reaction pathways were followed by intrinsic reaction coordinate47,48 computations, and high-accuracy, single-point energy calculations of density functional theory-optimized structures were performed with Møller–Plesset perturbation theory49. Among possible π-coordination complexes at C1–C2, C2–C3, C3–C4 and C9–C10 bonds, the π-complex at C9–C10 (K-region) was found to be most stable (9,10Pd). This may be due to the tendency of this bond to have the most olefinic (less aromatic) character17,50. We also calculated all possible transition states of insertion from these π-complexes to give alkylpalladium complexes (Fig. 3b). The formation of C9–Pd complex (9Pd–10Ph), which leads to APEX at the K-region, was found to be most favourable both kinetically and thermodynamically. Thus, the basis of K-region selectivity in our new APEX reaction has been supported by computational theory. Detailed computational studies of Pd/o-chloranil-catalysed C–H activation, including the present APEX reactions, will be reported in due course. Based on these calculations, we predict the most olefinic (least aromatic) K-region π-bond to be the first APEX reaction site in future functionalizations of related π-extended PAHs and nanographenes.

Multiple APEX and sequential APEX

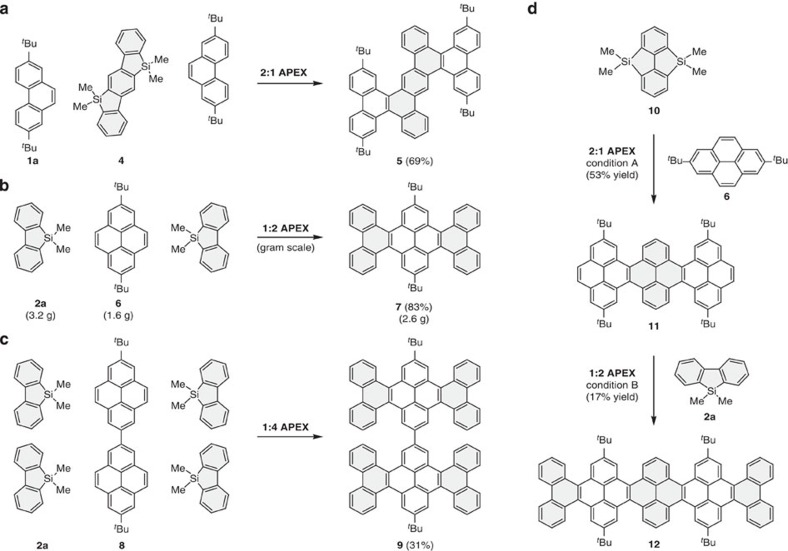

To showcase the utility of our APEX methodology in accessing a variety of nanographene (π-extended PAH) structures in a rapid and programmable manner, we examined several types of multiple APEX reactions (Fig. 4a–c). For example, a 2:1 APEX reaction occurs when treating ladder-type bis-silicon-bridged p-terphenyl 4 (ref. 51) with an excess of 2,7-di-tert-butylphenanthrene (1a) in the presence of Pd(CH3CN)4(SbF6)2/o-chloranil, to construct the dibenzodiphenanthroanthracene framework 5 in 69% yield (Fig. 4a). Other isomers were not observed in the reaction, highlighting the fidelity of the present method to specific reaction sites. An alternative mode of the double APEX reaction (1:2 APEX) was also possible by the reaction of 2,7-di-tert-butylpyrene 6 (1.6 g, 1.0 equiv) and dibenzosilole 2a (3.2 g, 3.0 equiv) in the presence of Pd(CH3CN)4(SbF6)2 (5 mol%) and o-chloranil (4.0 equiv) (Fig. 4b). It is noteworthy that the reaction could be conducted on a gram scale to yield di-tert-butylhexabenzotetracene 7 in 2.6 g (83% yield). The gram-scale synthesis clearly underscores the high capability of the present reaction conditions for multiple APEX reactions. Furthermore, the Pd(CH3CN)4(SbF6)2/o-chloranil system effectively promoted the one-shot fourfold APEX reaction of 7,7′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyrene 8 (1.0 equiv) with dibenzosilole 2a (10 equiv), to provide bihexabenzotetracene 9 in 31% yield (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4. Multiple APEX and sequential APEX.

Multiple APEX (a–c). (a) 2:1 APEX. Reaction conditions: 4 (1 equiv), 1a (5 equiv), Pd(CH3CN)4(SbF6)2 (5 mol%), o-chloranil (4 equiv), 1,2-dichloroethane, 80 °C, 2 h. (b) 1:2 APEX. Reaction conditions: 6 (1 equiv), 2a (3 equiv), Pd(CH3CN)4(SbF6)2 (5 mol%), o-chloranil (4 equiv), 1,2-dichloroethane, 80 °C, 8 h. (c) Reaction conditions: 8 (1 equiv), 2a (10 equiv), Pd(CH3CN)4(SbF6)2 (15 mol%), o-chloranil (10 equiv), 1,2-dichloroethane, 80 °C, 1 h. (d) Sequential APEX. 2:1 APEX conditions (A): 6 (3 equiv), 10 (1 equiv), Pd(CH3CN)4(SbF6)2 (5 mol%), o-chloranil (4 equiv), 1,2-dichloroethane, 80 °C, 6 h. 1:2 APEX conditions (B): 11 (1 equiv), 2a (4 equiv), Pd(CH3CN)4(SbF6)2 (15 mol%), o-chloranil (5 equiv), 1,2-dichloroethane, 80 °C, 4 h.

To further examine the applicability of APEX technology for the construction of larger molecules, sequential APEX reactions were investigated (Fig. 4d). Pleasingly, the 2:1 APEX reaction of 2,7-di-tert-butylpyrene 6 (3.0 equiv) with bis-silicon bridged biphenyl 10 (ref. 51) (1.0 equiv) under Pd(CH3CN)4(SbF6)2/o-chloranil conditions afforded tetra-tert-butylhexabenzohexacene 11 in 53% yield. The follow-up 1:2 APEX reaction of 11 (1.0 equiv) with dibenzosilole 2a (4.0 equiv) also took place to furnish the target decabenzooctacene framework 12 in 17% yield. In this particular reaction, we recovered a considerable amount of starting material likely to be attributed to poor solubility in the reaction media. Despite being relatively small in molecular size, the electronic structures of these nanographenes can be systematically altered. With the increase in molecular length, the HOMO-LUMO gap becomes smaller. In line with this trend, we observed decent red shift in both absorption and fluorescence (see Supplementary Fig. 41 for details).

Discussion

It should also be mentioned that we observed the first sign of the possibility of employing APEX in an oligomerization/polymerization manifold when we detected oligomers by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry analysis in the first 2:1 APEX reaction shown in Fig. 4d. Although we have not yet investigated this possible mode of reaction extensively, we envisage that the present APEX reaction could be applied to even larger molecules through judicious choice of solubilizing substituents on the substrates. Thus, the present result bodes well for the potential application of our APEX methodology to the bottom-up synthesis of graphene nanoribbons with controlled edge structures.

The present APEX methodology is complementary to the state-of-the-art two-step nanographene synthetic methods, thereby finding significant use in the ‘growth from template’ nanographene synthesis and in the late-stage fine-tuning of nanographene properties. Moreover, our APEX technology is not limited to the synthesis and functionalization of π-extended PAHs and nanographenes. One of the most significant features of the present APEX reaction is that unfunctionalized PAHs can be directly used for π-component assembly and π-extension without any pre-functionalization. Thus, various π-conjugated molecules made by many research groups (for many different purposes) will be suitable substrates for our APEX reaction, furnishing even more exciting classes of π-conjugated systems. The realization of APEX polymerization, the development of new APEX reactions for other PAH regions and acquisition of the first structure–property relationships for various nanographene structures are now ongoing in our laboratory.

Methods

Materials and characterization data

For the synthesis of all starting materials, siloles and π-extended PAHs, and their characterization, see Supplementary Methods. 1H, 13C and 19F NMR spectra were obtained for all compounds, see Supplementary Fig. 1–40. Ultraviolet–visible absorption and fluorescence spectra of 6, 11 and 12 are provided in Supplementary Fig. 41. Calculated energy surface of π-complexation and insertion are provided in Supplementary Fig. 42. Calculated energies of stationary points and their Cartesian coordinates are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. Effects of reaction parameters are provided in Supplementary Tables 2–4.

Typical procedure of K-region-selective APEX reaction

2,7-Di-tert-butyl-phenanthrene (1a: 58 mg, 0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), dimethyldibenzosilole (2a: 63 mg, 0.3 mmol, 1.5 equiv), Pd(CH3CN)4(SbF6)2 (7.4 mg, 10 μmol, 5 mol%), o-chloranil (98 mg, 0.4 mmol, 2.0 equiv) and a stirring bar were placed in a screw cap test tube. The tube was sealed with a perforated plastic cap and air was removed though a needle under reduced pressure. After back filling with nitrogen or argon, 1,2-dichloroethane (2 ml) was added and the needle was removed to seal up the test tube. The tube was fixed in an aluminum heating block and the mixture was stirred at 80 °C. After 2 h, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and then passed through a short pad of silica gel (eluent: CH2Cl2). After the organic solvents were removed under reduced pressure, the residue was purified by silica-gel chromatography (eluent: hexane) to afford 3,14-di-tert-butyldibenzo[g,p]chrysene (3aa) in 88% yield (77.0 mg) as a white powder.

Author contributions

K.I. conceived the concept. K.O., K.K. and H.I. conducted experiments. M.S. performed theoretical calculations. K.I and H.I. prepared the manuscript, with feedback from other authors.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Ozaki, K. et al. One-shot K-region-selective annulative π-extension for nanographene synthesis and functionalization. Nat. Commun. 6:6251 doi: 10.1038/ncomms7251 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-42, Supplementary Tables 1-4, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the ERATO programme from JST (K.I.), the Funding Program for Next Generation World-Leading Researchers from JSPS (220GR049 to K.I.) and KAKENHI from MEXT (26810057 to H.I.). K.O. and K.K. thank the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) for fellowships. We thank Dr Yasutomo Segawa (Nagoya University), Professor Cathleen M. Crudden (Queen’s University) and Dr Ayako Miyazaki (Nagoya University) for fruitful discussion and critical comments. Dr Keiko Kuwata (Nagoya University) is acknowledged for assistance in mass spectroscopy. Calculations were performed using the resources of the Research Center for Computational Science, Okazaki, Japan. ITbM is supported by the World Premier International Research Center (WPI) Initiative, Japan.

References

- Novoselov K. S. et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306, 666–669 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen M. J., Tung V. C. & Kaner R. B. Honeycomb carbon: a review of graphene. Chem. Rev. 110, 132–145 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geim A. K. Graphene: status and prospects. Science 324, 1530–1534 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Psula W. & Müllen K. Graphenes as potential material for electronics. Chem. Rev. 107, 718–747 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer D. R., Ruoff R. S. & Bielawski C. W. From conception to realization: an historical account of graphene and some perspectives for its future. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 9336–9344 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Hernandez Y., Feng X. & Müllen K. From nanographene and graphene nanoribbons to graphene sheets: chemical synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 7640–7654 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müllen K. Evolution of graphene molecules: structural and functional complexity as driving forces behind nanoscience. ACS Nano 8, 6531–6541 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson M. D., Fechtenkoetter A. & Müllen K. Big is beautiful – “aromaticity” revisited from the viewpoint of macromolecular and supramolecular benzene chemistry. Chem. Rev. 101, 1267–1300 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita A. et al. Synthesis of structurally well-defined and liquid-phase-processable graphene nanoribbons. Nat. Chem. 6, 126–132 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab M. G. et al. Structurally defined graphene nanoribbons with high lateral extension. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 18169–18172 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott L. T. et al. Geodesic polyarenes with exposed concave surfaces. Pure Appl. Chem. 71, 209–219 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Tsefrikas V. M. & Scott L. T. Geodesic polyarenes by flash vacuum pyrolysis. Chem. Rev. 106, 4868–4884 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J. M. et al. Atomically precise bottom-up fabrication of graphene nanoribbons. Nature 466, 470–473 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treier M. et al. Surface-assisted cyclodehydrogenation provides a synthetic route towards easily processable and chemically tailored nanographenes. Nat. Chem. 3, 61–67 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo T. H. et al. Large-scale solution synthesis of narrow graphene nanoribbons. Nat. Commun. 5, 3189 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X., Pisula W. & Müllen K. Large polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: synthesis and discotic organization. Pure Appl. Chem. 81, 2203–2224 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Harvey R. G. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Wiley-VCH (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Valencia J. R. et al. Controlled synthesis of single-chirality carbon nanotubes. Nature 512, 61–64 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omachi H., Nakayama T., Takahashi E., Segawa Y. & Itami K. Initiation of carbon nanotube growth by well-defined carbon nanorings. Nat. Chem. 5, 572–576 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fort E. H., Donovan P. M. & Scott L. T. Diels–Alder reactivity of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon bay regions: implications for metal-free growth of single-chirality carbon nanotubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 16006–16007 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fort E. H. & Scott L. T. One-step conversion of aromatic hydrocarbon bay regions into new unsubstituted benzene rings. A reagent for the low-temperature, metal-free growth of single-chirality carbon nanotubes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 6626–6628 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fort E. H. & Scott L. T. Gas-phase Diels–Alder cycloaddition of benzyne to an aromatic hydrocarbon bay region. Groundwork for the selective solvent-free growth of armchair carbon nanotubes. Tetrahedron Lett. 52, 2051–2053 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Jiao C., Huang K. W. & Wu J. Lateral extension of π conjugation along the bay regions of bisanthene through a Diels–Alder cycloaddition reaction. Chem. Eur. J. 17, 14672–14680 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi A., Hirano Y., Matsumoto K., Kurata H. & Kubo T. Facile synthesis and lateral π-expansion of bisanthenes. Chem. Lett. 42, 592–594 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Schuler B. et al. From perylene to a 22-ring aromatic hydrocarbon in one-pot. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 9004–9006 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fort E. H. & Scott L. T. Carbon nanotubes from short hydrocarbon templates. Energy analysis of the Diels–Alder cycloaddition/rearomatization growth strategy. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 1373–1381 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Clar E. & Zander M. Syntheses of coronene and 1: 2-7: 8-dibenzocoronene. J. Chem. Soc. 4616–4625 (1957). [Google Scholar]

- Thamatam R., Skraba S. L. & Johnson R. P. Scalable synthesis of quaterrylene: solution-phase 1H NMR spectroscopy of its oxidative dication. Chem. Commun. 49, 9122–9124 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochida K., Kawasumi K., Segawa Y. & Itami K. Direct arylation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons through palladium catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 10716–10719 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasumi K., Mochida K., Kajino T., Segawa Y. & Itami K. Pd(OAc)2/o-chloranil/M(OTf)n: a catalyst for the direct C–H arylation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons with boryl-, silyl-, and unfunctionalized arenes. Org. Lett. 14, 418–421 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Kawasumi K., Segawa Y., Itami K. & Scott L. T. Palladium-catalyzed C–H activation taken to the limit. Flattening an aromatic bowl by total arylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 15664–15667 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasumi K., Mochida K., Segawa Y. & Itami K. Palladium-catalyzed direct phenylation of perylene: structural and optical properties of 3,4,9-triphenylperylene and 3,4,9,10-tetraphenylperylene. Tetrahedron 69, 4371–4374 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki K., Zhang H., Ito H., Lei A. & Itami K. One-shot indole-to-carbazole π-extension by Pd-Cu-Ag trimetallic system. Chem. Sci. 4, 3416–3420 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Kawasumi K., Zhang Q., Segawa Y., Scott L. T. & Itami K. A grossly warped nanographene and the consequences of multiple odd-membered-ring defects. Nat. Chem. 5, 739–744 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funaki K., Kawai H., Sato T. & Oi S. Palladium-catalyzed direct C–H bond arylation of simple arenes with aryltrimethylsilanes. Chem. Lett. 40, 1050–1052 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto K., Zhang J., Housekeeper J. B., Marder S. R. & Luscombe C. K. C–H arylation reaction: atom efficient and greener syntheses of π-conjugated small molecules and macromolecules for organic electronic materials. Macromolecules 46, 8059–8078 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Segawa Y., Maekawa T. & Itami K. Synthesis of extended π-systems through C–H activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 66–81 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi J., Yamaguchi A. D. & Itami K. C–H bond functionalization: emerging synthetic tools for natural products and pharmaceuticals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 8960–9009 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wencel-Delord J. & Glorius F. C–H bond activation enables the rapid construction and late-stage diversification of functional molecules. Nat. Chem. 5, 369–375 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer W., Kos A. J. & Schleyer P. v. R. Regioselektive dimetallierung von aromaten. Bequemer zugang zu 2,2′-disubstituierten biphenylderivaten. J. Organomet. Chem. 228, 107–118 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Balch A. L. Oxidation of o-quinone adducts of transition metal complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 95, 2723–2724 (1973). [Google Scholar]

- Fox G. A. & Pierpont C. G. Periodic trends in charge distribution for transition metal complexes containing catecholate and semiquinone ligands. Metal-mediated spin coupling in the bis(3,5-di-tert-butyl-1,2-semiquinone) complexes of palladium(II) and platinum(II) M(DBSQ)2 (M=Pd, Pt). Inorg. Chem. 31, 3718–3723 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Ureshino T., Yoshida T., Kuninobu Y. & Takai K. Rhodium-catalyzed synthesis of silafluorene derivatives via cleavage of silicon−hydrogen and carbon−hydrogen bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 14324–14326 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J. Gaussian09, Revision E.01 Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford CT, (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D. Density functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648–5652 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P. Unified Theory of Exchange and Correlation Beyond the Local Density Approximation/Electronic Structure of Solids. (Eds Ziesche P. & Eschrig H.) 11–20 (Akademie Verlag 1991). [Google Scholar]

- Dunning T. H. & Hay P. J. Methods of Electronic Structure Theory/Modern Theoretical Chemistry. Ed Schaefer, III H. F. 3, 1–27Springer (1977). [Google Scholar]

- Hay P. J. & Wadt W. R. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for the transition metal atoms Sc to Hg. J. Chem. Phys. 82, 270–283 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S. Improved second-order Møller–Plesset perturbation theory by separate scaling of parallel- and antiparallel-spin pair correlation energies. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 9095–9102 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa T., Sekine M., Schaefer W. P. & Taube H. Preparation and characterization of a bis(pentaammineosmium(II)) pyrene complex. Inorg. Chem. 30, 449–452 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu M., Tatsumi H., Mochida K., Oda K. & Hiyama T. Silicon-bridge effects on photophysical properties of silafluorenes. Chem. Asian J. 3, 1238–1247 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-42, Supplementary Tables 1-4, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References