There is a tremendous potential to this moment in history when innovations in public health education can provide current and future leaders with the knowledge and tools needed to dramatically improve population health. The sea changes that we are experiencing in health care systems, demographics, health needs, and science are fueling both demand for improved health and health systems and the opportunity for public health to lead in accomplishing these improvements. Today’s public health students need an education that can support the evolution of their long careers, which will most likely evolve in focus over time and even across locales and sectors. Our current students will be leading in 2020 and 2050—and need to be prepared for both. This is a moment that requires schools of public health to move beyond the status quo into a new era of public health education. This issue offers a spotlight on innovations in public health education under way in North American Schools of Public Health.

THE CHANGING HEALTH LANDSCAPE

Across the globe, health needs are changing before our eyes. We are living in a world of longer lives, where investing in health preservation and prevention—especially of chronic diseases—across the full life course is becoming essential to the well-being of nations as well as to individuals. At the same time, demographic shifts—whether to cities for jobs or due to armed conflicts or climate change—have moved unprecedented numbers of people to cities, making us ever more an urban world. Meanwhile, many countries are trying to address widening disparities in health and resources while still combatting age-old scourges from malaria to malnutrition to maternal and infant death. The climate of health is changing, and with it systems and functions.

At the same time, economic and social forces are pushing more countries to recognize the merits of public health models of prevention. It has been well established that public health’s science of prevention and its translation into policies and practice creates 60% to 70% of the health of a population.1 Health systems like that of the United States that significantly underinvest in population health and prevention reap the dismal results: the United States’ health status has sunk, relatively, to the bottom of peer nations in recent years.2 This should not come as a surprise given that only three percent of US health expenditures go into prevention and public health.1 Unfortunately, the US corporate sector has taken the same approach, investing only two percent of their total health budget on prevention.3

Thus, we are at a moment where public health leadership is needed to create a true health system (i.e., one designed to maximize population health). This will involve reinvented education and a journey, in the United States and globally, to a 21st-century public health system. This new system would focus on effectively preventing both chronic conditions and infectious diseases, disability as well as injuries that confront our population, while delivering the emergency response needed. This future health system would prominently include a coordinated continuum of medical care of high quality, along with re-envisioned and synergistic public health and social care systems, supported by prevention policies, norms, and practices in every sector and locale of society that are aligned to create health. If this is a vision and goal for 21st century health systems, is our current public health education infrastructure sufficient to develop and prepare public health professionals who can take the lead in accomplishing this transition? As stated eloquently in the 2010 Lancet Commission report,4 health profession education needs to change in concert with needed changes in health systems.

AN EDUCATION FOR THE FUTURE

Our public health workforce needs the appropriate tools to tackle and address these many challenges and to support public health professionals’ ability to effectively lead change over the coming decades. In recent years, it has become increasingly evident that public health educators must develop a new education model that provides students with the grounding and skills to succeed in this new world order.

Taking up this call, the Lancet Commission report of 2010 proposed a next generation of global contents and standards for public health education4 that would position public health students to lead the design and conduct of the health systems that will optimize health. The report described two prior generations of public health education (science-based and problem-based) and called for a third generation that is

systems based to improve the performance of health systems by adapting core professional competencies to specific contexts, while drawing on global knowledge.4(p1924)

The Institute of Medicine5 and the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health (ASPPH) Framing the Futures Task Force6 are also aligned in recognizing the need for new leadership from public health professionals to develop the population health and health system that we need. The Framing the Futures Task Force further called for “innovative experiments, models and components in how to accomplish these goals,” to focus on the content that will meet 21st-century goals and the methods that can deliver that content most effectively and to a range of students and professionals.

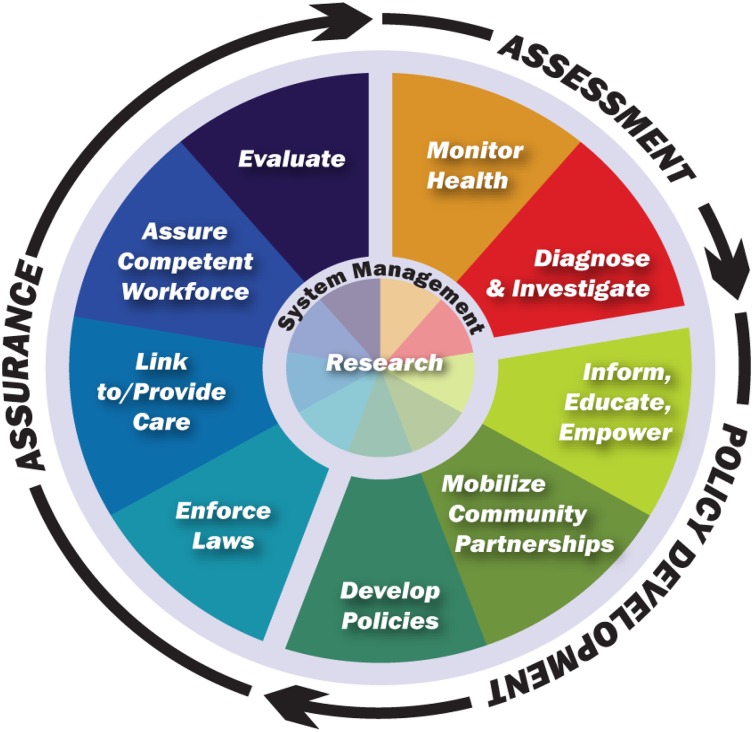

The ASPPH task force on “A Master of Public Health Degree for the 21st Century”7 has also provided schools and programs with guidance and recommendations on the more interdisciplinary and interprofessional content needed in today’s curriculums. We are also informed by models such as the US National Public Health Performance Standards, which define the 10 essential public health services (Figure 1)8 and which our students must be able to implement as appropriate to their future jobs.

FIGURE 1—

10 essential public health services.

Source. US National Public Health Performance Standards.8

FROM THEORY TO PRACTICE

Globally, many schools and programs of public health have been actively working on these questions of how to educate for this new future. In addition to the many taskforces and recommendations cited previously, we’ve turned to peer graduate programs in business, medicine, and others to learn from their transformations.

As the structure and effectiveness of health systems is key to population health, our schools need to increase their focus on this area. In a world where the solutions to almost all challenges in population health involve a complex system of issues that have to be addressed, understanding any one issue—such as maternal mortality prevention—has to be embedded in understanding the host of factors affecting that issue to develop effective and sustainable solutions.

It may sound like going back to the basics, but whether our students decide to focus on preventive medicine, health policy, qualitative or quantitative sciences, or environmental health, they will need to know how to use emerging prevention science. This core aspect of public health has taken the back seat for too long to medical interventions. Now is the moment to remind governments that the measurement of success for a health system is in preventing people from needing to seek treatment, not just in being able to offer treatment. Our students need to be fully steeped in the power of public health prevention to positively impact the health of populations if they are to successfully make this argument as alumni and public health practitioners.

Further, our students need to be able to integrate nontraditional public health capabilities—such as systems science, information technology, communications, and management—into their work. The current Ebola epidemic—with its many overwhelming logistical, social, and political challenges; misperceptions and misinformation; and management issues—attests to the heightened need for these skills.

There is no one formula for success in this venue. As each school tackles this complex and difficult undertaking, all the more so challenging in an era of budget cuts, new insights arise. Some schools are now experimenting with case studies as a means of guiding students through the complex decision-making processes that they will encounter in the workforce, while leadership exercises are also increasingly utilized. Cross-disciplinary teaching offers opportunities for students to learn public health in the classroom the way it is actually performed in the field.

This is, thus, a time of both opportunity and tremendous need for public health education and science—in a 21st-century iteration.

Acknowledgments

The Innovations in Public Health Education supplement was supported in part by the Josiah Macy Jr Foundation. Support for this supplement was also provided in part by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The author would also like to thank Rebekah Kharrazi, MPH, and Maria Andriella O’Brien, MPH, MBA, for their contributions in managing the supplement.

References

- 1.Schroeder SA. We can do better—improving the health of the American people. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(12):1221–1228. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa073350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woolf SH, Aron L Panel on Understanding Cross-National Health Differences Among High-Income Countries; Committee on Population; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; National Research Council; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; and Institute of Medicine. US Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Investing in Prevention. A National Imperative. New York, NY: The Vitality Institute Commission on Health Promotion and the Prevention of Chronic Disease in Working-Age Americans; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–1958. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Committee on Assuring the Health of the Public in the 21st Century. The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Acadamies Press, Institute of Medicine; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petersen DJ, Weist EM. Framing the Future by Mastering the New Public Health. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014;20(4):371–374. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Framing the Future Taskforce. A Master of Public Health Degree for the 21st Century: Key Considerations, Design Features, Critical Content of the Core. Washington, DC: Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Office for State, Tribal, Local and Territorial Support, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US). National Public Health Performance Standards Program. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nphpsp/essentialservices.html. Accessed on February 2, 2015.