Abstract

To determine the role of LPL for binding of lipoproteins to the vascular endothelium, and for the distribution of lipids from lipoproteins, four lines of induced mutant mice were used. Rat chylomicrons labeled in vivo with [14C]oleic acid (primarily in TGs, providing a tracer for lipolysis) and [3H]retinol (primarily in ester form, providing a tracer for the core lipids) were injected. TG label was cleared more rapidly than core label. There were no differences between the mouse lines in the rate at which core label was cleared. Two minutes after injection, about 5% of the core label, and hence chylomicron particles, were in the heart of WT mice. In mice that expressed LPL only in skeletal muscle, and had much reduced levels of LPL in the heart, binding of chylomicrons was reduced to 1%, whereas in mice that expressed LPL only in the heart, the binding was increased to over 10%. The same patterns of distribution were evident at 20 min when most of the label had been cleared. Thus, the amount of LPL expressed in muscle and heart governed both the binding of chylomicron particles and the assimilation of chylomicron lipids in the tissue.

Keywords: heart, muscle, adipose tissue, liver, triglycerides, nonesterified fatty acids, transgene

LPL is a key enzyme in lipid metabolism (1, 2). It is synthesized mainly by myocytes, adipocytes, and macrophages and is transported to the luminal surface of capillary endothelial cells by the help of an endothelial cell membrane protein, GPIHBP1 (3). Here the enzyme hydrolyzes TGs in TG-rich lipoproteins, i.e., chylomicrons and VLDLs. The released fatty acids are taken up by the tissue or mix with the plasma FFAs (4). The remnant lipoproteins are removed from the circulation by receptor-mediated processes mainly in the liver (5). The enzyme is expressed and regulated in a tissue-specific manner (1, 2). As an example, the activity in adipose tissue is relatively low between meals but rises postprandially (6). This has been suggested to govern when and to what extent lipids are delivered to the adipose tissue for storage (1, 2). On the other hand, it has been argued that the only role of the enzyme is to release the fatty acids in a form that can be transferred from lipoproteins into cells or onto albumin, and that the amount taken up by individual cells is usually governed by transport processes (7) and/or the metabolic balance within the cell (8) rather than by the rate at which the lipase releases fatty acids at endothelial sites adjacent to the cell.

The first step in chylomicron catabolism is that the lipoprotein particles bind to the endothelial surface, a process named margination. Goulbourne et al. (9) have demonstrated that the margination requires LPL bound to GPIHBP1. Deficiency of GPIHBP1, genetic or in mouse models, leads to equally severe hyperchylomicronemia as deficiency of LPL itself (10). In this setting normal amounts of LPL are produced, but do not reach the endothelial surface. Mouse genetic models with altered expression of LPL have been generated. Total LPL deficiency due to gene knockout leads to lethal hypertriglyceridemia within 18 h of life (11). By mating heterozygous LPL knockout mice with transgenic mice that express human LPL in either muscle (12) or heart (13), mouse lines have been generated that express the enzyme in only a single tissue. Here we have taken advantage of these mouse models to study to what extent the expression of LPL in a tissue governs initial binding and/or deposition of lipids in that tissue. For this we used rat chylomicrons, labeled in vivo with [3H]-retinol (which is incorporated into retinyl esters and serves as label for the core lipids and for the chylomicron particles) and [14C]oleic acid (which is incorporated in TGs and can be used to follow lipolysis of these).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animal procedures

Four groups of induced mutant mice (Table 1) were used for this study. L2 MCK denotes mice with a human LPL minigene driven by the promotor of the muscle creatine kinase gene (14). In these mice, human LPL is expressed in skeletal and cardiac muscle but not in other tissues. L2 LPL denotes mice with another human LPL minigene under control of 8 kb upstream regulatory sequences of the mouse LPL gene (15). These mice express human LPL in cardiac muscle but not in skeletal muscle or adipose tissue. Through cross-breeding of these lines with heterozygous LPL knockout mice, animals were generated that expressed the human transgene in the absence of the endogenous mouse gene, L0 MCK (11) and L0 LPL (15), respectively (Table 1). The mice had free access to chow and water.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the mice

| Group | EndogenousLPL | Human LPL | Number of Mice | Weight (g) | |||

| Skeletal Muscle | Cardiac Muscle | Male | Female | Male | Female | ||

| WT | Yes | — | — | 5 | 7 | 30.0 ± 1.8 | 24.9 ± 0.4 |

| L2 MCK | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5 | 7 | 29.0 ± 1.1 | 23.6 ± 0.6 |

| L0 MCK | — | Yes | Yes | 6 | 4 | 31.6 ± 0.8 | 24.4 ± 2.1 |

| L2 LPL | Yes | — | Yes | 6 | 6 | 30.0 ± 1.2 | 22.8 ± 0.8 |

| L0 LPL | — | — | Yes | 6 | 6 | 28.6 ± 1.4 | 22.2 ± 1.4 |

The L2 MCK mice used here were the medium expressors described by Levak-Frank et al. (14) and were designated L2 MCKM in that publication. At the age studied here, these mice have relatively normal body composition, but somewhat less muscle mass than WT mice. Later, they develop a severe myopathy characterized by muscle fiber degeneration, fiber atrophy, glycogen storage, and extensive proliferation of mitochondria and peroxisomes. Levak-Frank et al. (14) reported that LPL activity (human plus endogenous mouse LPL) was increased 8.1-fold in skeletal muscle and by 55% in the hearts of these mice, and Hoefler et al. (16) found similar values. Postheparin plasma LPL, as a measure of total body functional LPL, was about double in L2 MCK compared with WT mice (14).

L0 MCK mice were first reported by Weinstock et al. (11). They found that homozygous LPL knockout mice develop a lethal hypertriglyceridemia and die within 18 h after they begin to ingest lipids with the milk. Introduction of muscle-specific LPL expression in the L0 MCK mice rescued the knockout mice and normalized their lipoprotein pattern. No data on lipase activities in these mice have previously been published.

The L2 LPL and L0 LPL mice were described by Levak-Frank et al. (13) and were designated L2 LPL2 and L0 LPL2 in that publication. In L2 LPL mice, the enzyme activity in cardiac muscle was slightly increased, while it remained normal in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle when compared with WT mice. LPL activity in L0 LPL mice was slightly decreased in the heart, while undetectable in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle. Postheparin plasma LPL activity was increased 180% in L2 LPL mice, while it decreased 18% in L0 LPL mice. Both these groups of mice had normal body weight and body composition. However, the absence of LPL in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle caused a decrease in polyunsaturated fatty acids by 90% and 75%, respectively, while fatty acid composition in cardiac muscle was unchanged.

Chylomicrons

Male nonfasting Sprague Dawley rats (Moellegaard Breeding Centre, Skensved, Denmark) weighing 220–280 g were used for preparation of chylomicrons as described (4). They were anesthetized and a thin plastic tube was placed in the thoracic duct and a second tube in the stomach. After the operation, the rats were kept in restraining cages. 11,12-[3H]retinol (150 μCi) (Amersham, UK) and 150 μCi 9,10-[14C]oleic acid (Amersham, UK) in 5 ml 10% Intralipid® (Pharmacia, Stockholm, Sweden) was infused intra-gastrically. Lymph was collected during 6 h. Chylomicrons were then isolated by ultracentrifugation as described. In the chylomicrons, [3H]retinol is present mainly as retinyl ester [>92% according to Hultin, Savonen, and Olivecrona (4)], and therefore provides a tracer for the core lipids and the chylomicron particles. More than 97% of the labeled oleic acid is in TGs (4). The chemical amount of TGs in the chylomicron preparations was determined by an enzymatic kit from Boehringer Mannheim, Germany.

The procedures for preparation of chylomicrons in rats and for study of their metabolism in mice were approved by the animal ethics committee at Umeå University.

Chylomicron turnover

Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (Nembutal® Lundbeck, Copenhagen, Denmark) and rat lymph chylomicrons, corresponding to 1 mg TG per mouse, were injected into one of the exposed jugular veins. The injected doses of radioactivities were 320,000 dpm [3H]retinyl ester and 690,000 dpm 14C-TG. Blood samples of about 50 μl were taken from the retro-orbital plexa at two of the time points, 1, 2, 3, 7, or 13 min. A final blood sample, 150–200 μl, was taken after 2 or 20 min from the heart. The heart was then immediately extirpated. Tissue samples were removed, weighed, and frozen.

The blood samples were immediately transferred to tubes containing 1.2 ml isopropanol-heptane-1 M H2SO4 (40:10:1) to inhibit further lipolysis. The samples were then treated as described elsewhere to separate a neutral lipid and a FFA fraction (4). Later, the tissue samples were homogenized and labeled lipids were extracted in chloroform:methanol as described. The carcasses of six animals from each of the WT, the L2 MCK, and the L0 LPL groups were saponified in 20 g KOH, 20 ml water, and 60 ml 95% ethanol. Then 50% ethanol was added to a final volume of 200 ml and lipids were extracted to give a fatty acid and a non-fatty acid fraction, as previously described (4). Aliquots were taken from the blood and tissue extracts and the radioactivity determined in a LKB-Pharmacia 1214 β-counter. All samples were counted for 5 min and background radioactivities were subtracted.

The blood volume was taken to be 7.7% of body weight. The whole heart was homogenized. Weights for individual hearts are not available. The average weight of hearts in a group of similar mice was 0.47% of body weight. The average sample from M. quadriceps was 0.125 ± 0.004 g (n = 88). The average weight of the liver was 1.38 ± 0.49 g (n = 58).

Kinetic analysis

The turnover of core label and TG label was initially calculated for each individual mouse by fitting the blood data as two mono-exponential decay functions with a common intercept using SAAM II version 2.3 (The Epsilon Group, Charlottesville, VA). Each datum was assigned a fractional standard deviation of 0.05. The confidence intervals were calculated using Pop-Kinetics version 2.3 (The Epsilon Group), which determines the confidence intervals of the kinetic parameters using Monte-Carlo simulation. A sample of 100 random populations was used to determine the 95% confidence intervals for an intercept common to core label and TG label and separate fractional catabolic rates for groups of mice as specified in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Kinetic parameters for chylomicron clearance

| Parameter | WT | L2 MCK | L0 MCK | L2 LPL | L0 LPL |

| Total (n) | 12 | 12 | 10 | 12 | 12 |

| Intercept (%) | 92.4 (88.9–96.7) | 94.9 (84.0–103) | 85.6 (71.3–97.6) | 93.9 (76.6–110) | 90.3 (84.3–95.3) |

| FCR core (min−1) | 0.091 (0.073–0.108) | 0.081 (0.056–0.118) | 0.104 (0.069–0.143) | 0.090 (0.074–0.105) | 0.082 (0.068–0.097) |

| FCR TG (min−1) | 0.134 (0.118–0.157) | 0.128 (0.095–0.174) | 0.170 (0.145–0.206) | 0.145 (0.129–0.164) | 0.114 (0.097–0.130) |

| Female (n) | 7 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 6 |

| Intercept (%) | 90.3 (86.7–94.9) | 91.8 (79.8–102.5) | 78.7 (60.7–93.8) | 77.3 (65.0–93.7) | 89.3 (83.6–93.9) |

| FCR core (min−1) | 0.107 (0.090–0.121) | 0.111 (0.076–0.146) | 0.127 (0.118–0.139) | 0.095 (0.074–0.120) | 0.097 (0.074–0.118) |

| FCR TG (min−1) | 0.141 (0.122–0.174) | 0.155 (0.092–0.230) | 0.190 (0.168–0.217) | 0.158 (0.132–0.187) | 0.121 (0.101–0.162) |

| Male (n) | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Intercept (%) | 96.5 (87.6–103.3) | 99.7 (85.8–114.9) | 88.1 (64.0–105.8) | 111.7 (93.8–124.6) | 91.9 (82.6–96.3) |

| FCR core (min−1) | 0.072 (0.065–0.079) | 0.054 (0.039–0.069) | 0.100 (0.047–0.144) | 0.086 (0.062–0.101) | 0.066 (0.056–0.077) |

| FCR TG (min−1) | 0.128 (0.102–0.144) | 0.104 (0.063–0.127) | 0.142 (0.101–0.182) | 0.127 (0.114–0.140) | 0.102 (0.082–0.123) |

Conditions as in Fig. 1. The data for core and TG label in the blood for each mouse was fitted to a mono-exponential decay function with common intercept for core and TG label using SAAM II. Parameter estimates for the group and confidence intervals were calculated using Pop-Kinetics. Only mice where three blood samples were obtained were included in the calculations. The parameters were grouped and the data are presented as parameter estimates (95% confidence interval). FCR, fractional catabolic rate.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± SEM if not otherwise specified. For statistical analysis, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test in SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac, version 21.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) was used for tissue data. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test in GraphPad Prism 6.0e for Mac (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) was used for analysis of SAAM II/Pop-Kinetics parameter estimates. Differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the mice

The effects of the different genotypes on general health, growth curves, and body mass composition have been reviewed elsewhere (15). The mice used in the present study were 12–16 weeks old. There were no significant differences in body weight between the groups, but within each group females had lower weights than males (Table 1). Table 2 lists lipase activities in tissues of groups of mice corresponding to those used in this study. In the L2 MCK mice overexpressing human LPL in muscles on the normal mouse background, LPL activity was increased about 10-fold in skeletal muscle and slightly increased also in the heart. In the L0 MCK mice expressing human LPL in muscles on a knockout background, LPL activity was about 5-fold normal in skeletal muscle and half normal in cardiac muscle. The L2 LPL mice that overexpress human LPL in cardiac muscle on the normal mouse background had about 5-fold increased LPL activity in the heart. The values for skeletal muscle were somewhat higher than in the controls, but this was not statistically significant. The L0 LPL mice that express human LPL in cardiac muscle on a knockout background had slightly higher LPL in the heart than normal mice, whereas LPL activity in skeletal muscle was not significantly different from zero.

TABLE 2.

LPL activities in WT and genetically modified mice

| Group | Skeletal Muscle (mU/g Wet Weight) | Cardiac Muscle (mU/g Wet Weight) |

| WT | 69 ± 11 | 516 ± 131 |

| L2 MCK | 662 ± 83 | 785 ± 106 |

| L0 MCK | 370 ± 43 | 217 ± 50 |

| L2 LPL | 93 ± 25 | 2,431 ± 348 |

| L0 LPL | 11 ± 13 | 733 ± 423 |

These values are for separate groups of mice corresponding to those used in the studies on chylomicron metabolism.

Clearance from blood

Doubly labeled rat lymph chylomicrons were injected intravenously in the groups of mice described in Table 1. The disappearance of the two labels from the blood could be fitted to mono-exponential functions (Fig. 1). For the WT mice, the calculated half-lives were 7.6 min and 5.2 min for core and TG label, respectively. The fractional catabolic rates for core label in the four groups of mutant mice were not significantly different from those observed in the WT mice (Table 3), but the TG label was cleared faster in L0 MCK and slower in L0 LPL mice than in the other three groups of mice. There was a tendency in each of the groups that female mice cleared the chylomicrons faster, but it was not possible to discriminate whether this was a sex effect or because the females had lower body mass.

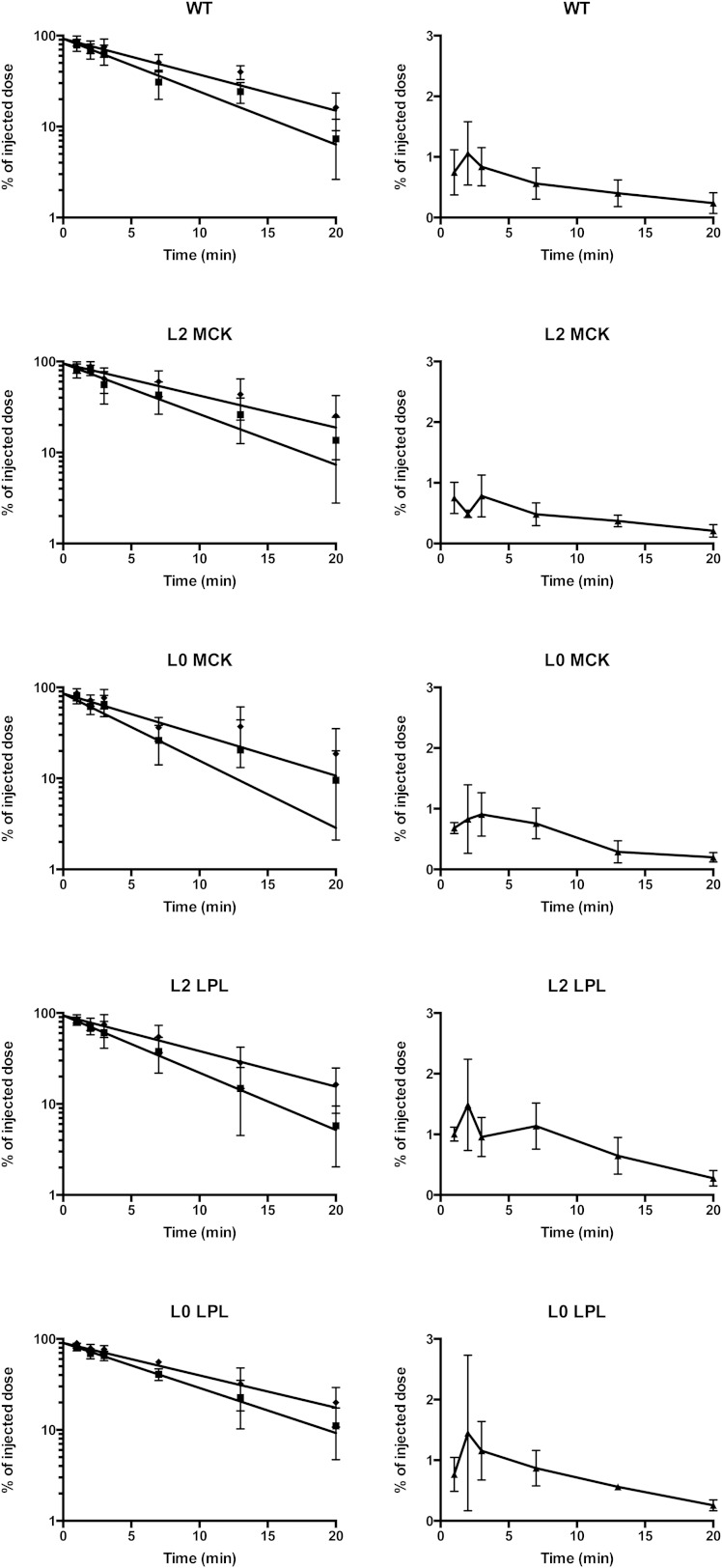

Fig. 1.

Disappearance from the blood of core and TG label and appearance of radiolabeled FFAs. Doubly labeled rat lymph chylomicrons were injected intravenously into anesthetized mice. From each mouse, three blood samples were taken. One was at the end of the experiment, 20 min. The other samples were taken at two of the following times: 1, 2, 3, 7, or 13 min. Calculations are based on the weight of the sample and a blood volume of 7.7% of body weight. The left panels show core (filled diamonds) and TG label (filled squares). The scale is logarithmic. The right panels show FFAs (filled triangles). The scale is linear. Lines in the left panels show data fit for each group as described in Table 3. Values shown as mean ± SEM.

At the end of the experiment, 20 min, 16.2 ± 2.2% of the core label remained in the blood in WT mice (Fig. 1). The amounts present in the other four groups were not significantly different, whether tested for the entire groups (25.3 ± 4.9%, 18.6 ± 5.5%, 16.4 ± 2.5%. and 19.7 ± 2.9% in the L2 MCK, L0 MCK, L2 LPL, and L0 LPL mice, respectively) or for males and females separately. This reinforces the conclusion that chylomicron particles were cleared at normal rates in the mice that overexpressed LPL or that expressed LPL in only one tissue.

The TG label was cleared more rapidly than the core label (Table 3). In the WT mice, only 7.3 ± 1.4% of the TG label was in the blood at 20 min compared with 16.2 ± 2.2% for the core label (Fig. 1). Hence, more than half of the TGs had been lost from the particles. The values were similar in the other four groups of mice, and there was no significant difference between the groups whether tested for TG label in the blood at 20 min or for the ratio of TG to core label (“the lipolysis index,” 1.0 in the chylomicrons, as injected). This suggests that the chylomicrons had been acted on by LPL to similar extents in the mice that overexpressed LPL or that expressed LPL in only one tissue, as in the WT mice.

Labeled fatty acids rapidly appeared in the plasma FFA fraction (Fig. 1). In the WT mice, 1.06 ± 0.26% of the radioactivity from the injected chylomicrons was present as FFAs in the blood at 2 min (Fig. 1). The FFA radioactivity then decreased again and was about 0.24 ± 0.05% at 20 min. For the L2 MCK and the L0 MCK mice, all data points fell within the 95% confidence interval for the WT mice. For the L2 LPL mice, the values tended to be higher. In the time interval 7–13 min, six of ten values were above the 95% confidence interval for WT mice. At 7 min, the values for L2 LPL mice were significantly higher than for WT mice when compared by a t-test (1.14 ± 0.16% vs. 0.56 ± 0.11%, P < 0.012). This suggests that in these mice (that express human LPL in cardiac muscle in addition to normal mouse LPL) more of the fatty acids from chylomicron TGs recirculated in the blood as FFAs. Also, in the L0 LPL mice (that express human LPL in cardiac muscle on a knockout background) there was a tendency toward higher radioactivity in the plasma FFAs, but this was less pronounced than in the L2 LPL mice.

Initial distribution of label

Figure 2 shows data for the heart and Fig. 3 data for skeletal muscle (M. quadriceps), the tissues directly affected by the induced mutations. Data for the liver are given in Fig. 4. The first time, 2 min, was chosen so that a sufficient fraction of the injected labeled chylomicrons should have left the blood, and radioactivity in the tissues could be assessed with some precision. Core radioactivity at this time should reflect the initial binding of chylomicrons. The amount of core label that remained in the blood at this time was not significantly different between the groups. Taking a mean of all mice returned a value of around 70%. Hence about 30% of the chylomicron particles had left the blood.

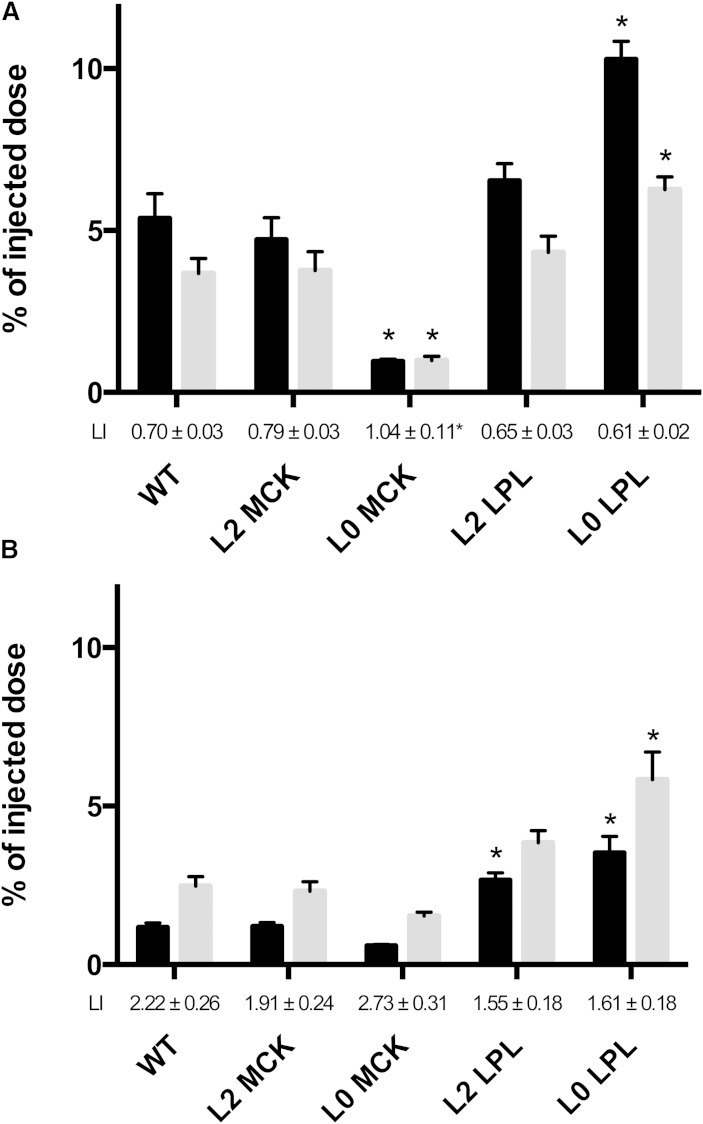

Fig. 2.

Chylomicron labels in the heart at 2 and 20 min. Doubly labeled rat lymph chylomicrons were injected intravenously into anesthetized mice. A final blood sample was taken 2 or 20 min later, and the animals were euthanized. The heart was immediately extirpated. The n = 6 in each group at 2 min (A); n as specified in Table 1 in the 20 min groups (B). Values are percent of injected dose per organ. LI, lipolysis index (TG label/core label, 1.0 in the chylomicrons as injected). Black bars, core label; gray bars, TG label. *P < 0.05, any of the genetically modified mice versus WT mice.

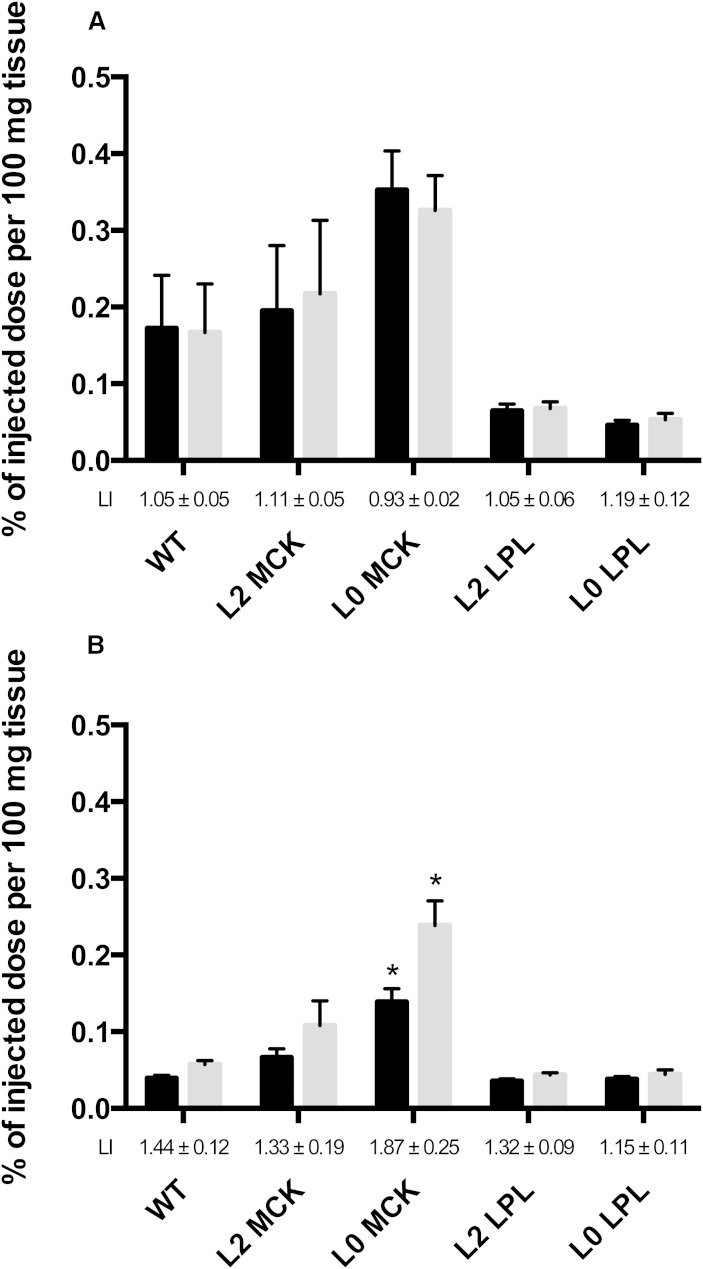

Fig. 3.

Chylomicron labels in M. quadriceps at 2 and 20 min. Same experiment as Fig. 2. Values shown as percent of injected dose per 100 mg wet weight.

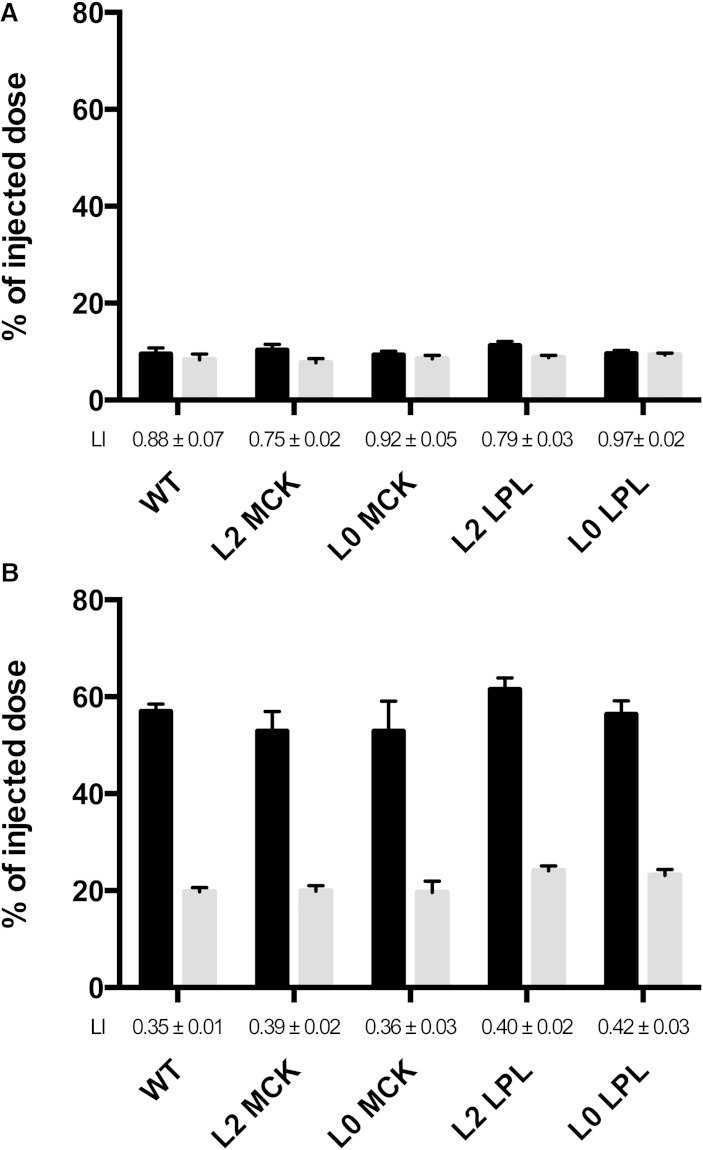

Fig. 4.

Chylomicron labels in the liver at 2 or 20 min. Same experiment as Fig. 2. Values are percent of injected dose per organ.

There was a relation between the LPL activity and the binding of chylomicrons in the heart (Table 2, Fig. 2A). The L0 LPL mice, that express LPL only in heart, had the highest core radioactivity in the heart, almost twice that in WT mice. In the L0 LPL mice and in the WT and L2 LPL mice, TG label was about one-third lower than core label (lipolysis index 0.61, 0.70, and 0.65). Hence, the chylomicrons that had bound in the hearts of these mice had undergone lipolysis, and the fatty acids had been lost by oxidation or by return to the blood as FFAs. In contrast, the L0 MCK mice, that have low LPL activity in the heart, showed low binding (core label less than one-fifth of that in WT mice) and no significant lipolysis (lipolysis index, 1.04).

The picture was reversed in the skeletal muscle (M. quadriceps) (Fig. 3A). The highest core label was in the L0 MCK mice (that express human LPL in skeletal muscle) and the lowest was in the L0 LPL and the L2 LPL mice (that express human LPL in the heart), again showing a relation between LPL activity and localization of chylomicrons. The differences in core label were large, about 5-fold, between the L0 LPL and the L0 MCK mice.

About 10% of the core label was in the liver at 2 min. The estimated amount of label in the blood remaining in the liver had been subtracted out so that the values in Fig. 4 represent real net binding/uptake. There was no significant difference between the genotypes in either core or TG label. The lipolysis index was significantly different from 1.0 in WT, L2 MCK, and L2 LPL mice, but not in L0 MCK and L0 LPL mice. These data show rapid uptake of chylomicron particles into the liver already within the first 2 min, in some cases with little lipolysis.

Distribution of label after 20 min

The total recovery (sum of all pieces taken out plus the digested carcass) of labeled retinol was about 80% in the WT mice after 20 min. Hence, only a small fraction had been degraded, and tissue retinol radioactivity reflects rather accurately where the particles were bound or had been taken up. Sixteen percent remained in the blood, about 55% was in the liver, and about 6% was in the spleen (data for spleen not shown). Together these three tissues accounted for about 90% of the retinol radioactivity recovered. The retinol radioactivity found in the heart and skeletal muscle was relatively low, but higher than could be accounted for by blood remaining in the tissue.

The distribution of core label had changed radically compared with that at 2 min. In the heart and skeletal muscle, the initially high core label had decreased (compare Fig. 2A, B and Fig. 3A, B), for instance from 5% to 1% of the injected dose in the heart of WT mice. This demonstrates that, after initial binding in these tissues, chylomicron particles had returned to the blood. In the liver, the core label had increased several-fold from 2 to 20 min, reflecting uptake of chylomicrons/remnants. For the heart and skeletal muscle, the patterns of radioactivity between the groups of mutant mice were, in most cases, maintained (Figs. 2, 3). For instance, in the heart of the L0 LPL mice, the core label had decreased from 10 to 3.5%, but was still higher than WT mice. L0 MCK mice were still the lowest. In contrast to the heart and skeletal muscle, the core radioactivity in the liver had increased and was around 55% of the injected dose in all five groups of mice (Fig. 4).

By 20 min, the total recovery of TG label had decreased to 56% in the WT mice, showing that nearly half of the chylomicron fatty acids had been oxidized. Hence, the data on tissue distribution of fatty acid radioactivity must be interpreted with caution. In most cases they underestimate the actual uptake, and this factor may differ substantially between tissues. At 20 min, TG label was higher than core label in the heart in most groups of mice (Fig. 2), indicating that fatty acids from chylomicrons had been incorporated into tissue lipids. The exception was the L0 MCK mice that have no LPL in heart. In skeletal muscle of WT mice, and the mice that overexpress LPL in skeletal muscle (L2 MCK and L0 MCK), the TG label was higher than the core label at 20 min.

DISCUSSION

The first event in catabolism of TG-rich lipoproteins is that they attach to sites at the vascular endothelium. Goulbourne et al. (9) have recently shown that this “margination” requires GPIHBP1-bound LPL. There is much previous evidence that the more LPL there is in a tissue, the more chylomicron lipids are taken up there (4, 17, 18). This is a direct effect of the lipase molecule as such. Mutant catalytically inactive LPL also has this effect (19). We speculated that the margination of chylomicrons in a tissue should reflect the LPL expression in that tissue. If so, a large fraction of injected chylomicrons should marginate in the tissue when the LPL activity is high. This prediction was borne out in the present study. In the WT mice, about 5% of the chylomicrons were recovered in the heart 2 min after injection, even though the heart makes up less than 0.5% of body weight. This supports a role for LPL, but is not conclusive. LPL-independent binding sites might be particularly abundant in the heart. The mutant mice provided more direct evidence for the involvement of LPL. In the L0 MCK mice, that express low amounts of LPL in heart, less than 1% of the chylomicrons located to the heart. In L0 LPL mice, who express LPL only in heart, more than 10% of the chylomicrons were recovered in the heart 2 min after injection. This is double the amount in WT mice and more than 10 times the amount in L0 MCK mice, strongly supporting a direct role for LPL in binding of chylomicrons to the vascular endothelium. This makes good physiological sense, as TG-rich lipoproteins should only bind to sites where they can be acted upon by the lipase.

A major limitation of our study is that we have measured LPL activity in homogenates of the tissues, not the LPL that is at the endothelium (“intravascular LPL” also called “functional LPL”). We rely on the assumption that the intravascular LPL represents a similar fraction of total tissue LPL in the different groups of mice. The intravascular LPL makes up only a fraction of the tissue total. This has been studied using the perfused heart as a model (20–22). When heparin is added to the perfusion medium, there is a rapid burst of LPL activity within the first few minutes that is commonly taken to represent the LPL present at or near the endothelial surface. In rat hearts, the LPL activity released in 5 min represents only 15–40% of tissue total (23), depending on the nutritional state of the rat. Yet, after a washout with heparin, the perfused rat heart has lost nearly all ability to take up lipids from chylomicrons (20). Further evidence that it is the intravascular LPL that is relevant for binding and catabolism of lipoproteins comes from studies on GPIHBP1 knockout mice (10). These mice accumulate TG-rich lipoproteins in the blood to a similar extent as seen in LPL deficiency, despite normal levels of tissue LPL activity. In this situation LPL is produced and secreted by the parenchymal cells, but cannot transfer to the vascular lumen because the carrier GPIHBP1 is lacking.

Another concern is the possibility that LPL is redistributed with blood from the sites where it is produced to endothelial surfaces in other tissues. Olafsen et al. (24) have presented evidence that some of the LPL found in mouse lung comes from elsewhere. In the systemic circulation in humans (25) and in rats (23), there are substantial amounts of inactive LPL protein, but very low levels of active LPL. A direct study of arteriovenous differences of LPL over adipose tissue and skeletal muscle in humans returned very low values (26). In perfused rat hearts, the outflow of active LPL corresponds to about 0.1% of tissue total per minute (23). This should be compared with an estimated turnover time for the enzyme of about 2 h (27). In the present study, the patterns of LPL activity reflected the genotypes. The L0 LPL mice, who do not express LPL in skeletal muscle, displayed very low LPL activity in muscle, not significantly different from zero. Hence, redistribution of active LPL is low or moderate and would tend to diminish the difference between the genotypes and, if anything, strengthen our conclusions.

The drastic differences in tissue expression of LPL in the genetically modified mice had little or no effects on the clearance of the injected chylomicrons. The calculated fractional catabolic rates were similar in all five groups of mice, and this was true both for TG label and for core label. That the clearance rates were similar in WT and mutant mice is in agreement with earlier observations that mice with tissue-specific expression of LPL have normal or even sub-normal plasma TG levels (13). Hence, differences in the expression of LPL, within the limits that our genetic models provided, do not markedly affect overall chylomicron clearance. This is also in concert with observations that parameters of plasma TG metabolism correlate only weakly to measures of LPL activity in postheparin plasma in humans (1, 2), and that clearance of chylomicrons occurs at the same rate in fed and fasted rats (4), even though LPL activity in their tissues changes markedly with the nutritional state (1, 2).

Not all of the fatty acids released by LPL are taken up by the tissue. Some return to the blood as FFAs (4), and there is evidence that this is a large fraction of the fatty acids from the chylomicrons. When chylomicrons were perfused through rat adipose and mammary tissue, respectively, 45 and 35% of the fatty acids were released to the medium as FFAs (28). After a fat meal, in humans there is a large change in composition of plasma FFAs, suggesting that many of the fatty acids come from lipolysis of chylomicrons (29). Net release of chylomicron-derived FFAs has been demonstrated by measurement of arteriovenous differences over adipose tissue in humans (30). In experiments similar to the present ones, Hultin, Savonen, and Olivecrona (4) analyzed the appearance of labeled FFAs after injection of labeled chylomicrons in rats. Kinetic modeling indicated that 50% or more of the fatty acids mixed with the same pool that plasma FFAs mix with. In the present experiments, we observed similar time curves indicating that in mice also, a large fraction of chylomicron fatty acids recirculate in the form of FFAs. The time curves for radioactivity in FFAs were similar in most of the genetically modified mice as in WT mice, but in the mice overexpressing LPL in the heart (L2 LPL), reappearance of label in FFAs was significantly above that in WT mice. Lipolysis by LPL localized in a small segment of the vascular tree, e.g., the heart, is apparently enough to feed similar amounts of fatty acids to the plasma FFA pool. These observations help explain how expression of LPL in a single tissue can support relatively normal lipoprotein and energy metabolism (15).

Available evidence indicates that chylomicrons, as they appear in chyle, bind in the heart with high affinity. A kinetic study showed that in rats, chylomicrons that locate in the heart stay for several minutes (31). Whether they stay at one site or roll slowly from one binding site to the next is not known. They may be sequestered by projections from the endothelial cells or even be internalized in vesicles in the endothelial cell (32). Anyhow, the particles were rapidly lipolyzed. Within 2 min, the lipolysis index in the heart had decreased to 0.70 ± 0.03, 0.61 ± 0.02, and 0.65 ± 0.03 in the WT, L0 LPL, and L2 LPL mice, respectively. A typical chylomicron contains 1,000,000 TG molecules. The lipase splits about 1,000 ester bonds per second (2). Hence, at least 10 lipase molecules have acted on the chylomicron during the first 2 min, providing a strong cooperative binding to the endothelial sites. After a few minutes, the particles return to the blood as partially lipolyzed “remnant” particles that have reduced affinity for binding-lipolysis sites and their main fate is removal by the liver (5). These processes are reflected in our data with initial binding of chylomicrons in peripheral tissues as evidenced by the core label. With time, the core label decreased in most tissues but increased in the liver. The amount found there at 20 min was similar for all five genotypes, indicating that the processes involved in hepatic uptake of chylomicrons/remnants are not markedly affected by where in the organism the lipolysis takes place.

At 20 min, TG label had increased in most tissues. This presumably reflects lipolysis and incorporation of chylomicron fatty acids into tissue lipids. The amount of fatty acid label in tissues of the mutant mice after 20 min reflected the pattern of binding at 2 min. Hearts with high LPL activity had incorporated more fatty acids into cellular lipids than hearts with low LPL activity. The same was true for skeletal muscle. There was considerably more fatty acid radioactivity in the L0 MCK mice that express LPL only in muscle. These data support a direct relation between the LPL activity in the tissue, the binding and hydrolysis of chylomicron TGs, and the uptake and deposition of lipolysis products in the tissue. This is in accord with earlier studies that demonstrate that the tissue distribution of radioactive fatty acids is substantially different if they are injected as components of chylomicron TGs compared with if they are injected as albumin bound FFAs (4, 33). The site where lipolysis occurs plays an important role in determining where the fatty acids end up.

Significant retinol/retinyl ester radioactivity remained in the tissues at 20 min, much more than could be accounted for by the blood in the tissue. The amounts varied markedly between the mouse lines. In a study in rats, Hultin, Savonen, and Olivecrona (4) found that about 30% of injected chylomicron retinol radioactivity located in extrahepatic tissues in rats. They noted a clear effect of the nutritional state on the distribution of the retinyl label into heart and adipose tissue. There was more retinyl label in the state when LPL is upregulated, i.e., more in adipose tissue of fed compared with fasted rats and more in the heart of fasted rats compared with fed. This suggested a relation between LPL activity, fatty acid uptake, and uptake of retinol label. The same correlation is evident in the present data. The mice that expressed LPL in cardiac muscle only (L0 LPL) had more core label in the heart than WT mice at the end of the experiment (20 min). The mice that expressed LPL in muscle only (L0 MCK) had less label in the heart, but more label in the skeletal muscle. These data indicate that some core lipids are taken up with the lipolysis products. This was observed before by Scow, Chernick, and Fleck (28) on perfusion of chylomicrons through rat mammary and adipose tissue, and by Fielding, Renston, and Fielding (34) in perfusions of rat hearts. It has been shown by several groups that LPL catalyzes transfer of nonpolar lipids from emulsion droplets to cells, so-called selective uptake, and this is not dependent on the lipase activity (35). More recently Bartelt et al. (36) demonstrated LPL-mediated uptake of core constituents from lipid emulsions in activated brown adipose tissue. This was further studied by Khedoe et al. (37), who concluded that most of the uptake of core lipid constituents depended on lipolysis.

Lipase action is a necessary step for the catabolism of chylomicrons. The present study demonstrates that the distribution of LPL between the tissues determines where the lipids are taken up, but has little influence on the rate of the overall process of clearance or on hepatic uptake of the chylomicrons/remnants.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Medical Research Council and from the Austrian Science fund.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang H., Eckel R. H. 2009. Lipoprotein lipase: from gene to obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 297: E271–E288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olivecrona T., Olivecrona G. 2009. The ins and outs of adipose tissue. In Cellular Lipid Metabolism. C. Ehnholm, editor. Springer, New York. 315–369. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young S. G., Zechner R. 2013. Biochemistry and pathophysiology of intravascular and intracellular lipolysis. Genes Dev. 27: 459–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hultin M., Savonen R., Olivecrona T. 1996. Chylomicron metabolism in rats: lipolysis, recirculation of triglyceride-derived fatty acids in plasma FFA, and fate of core lipids as analyzed by compartmental modelling. J. Lipid Res. 37: 1022–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper A. D. 1997. Hepatic uptake of chylomicron remnants. J. Lipid Res. 38: 2173–2192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergö M., Olivecrona G., Olivecrona T. 1996. Diurnal rhythms and effects of fasting and refeeding on rat adipose tissue lipoprotein lipase. Am. J. Physiol. 271: E1092–E1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg I. J., Eckel R. H., Abumrad N. A. 2009. Regulation of fatty acid uptake into tissues: lipoprotein lipase- and CD36-mediated pathways. J. Lipid Res. 50(Suppl): S86–S90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frayn K. N., Coppack S. W., Fielding B. A., Humphreys S. M. 1995. Coordinated regulation of hormone-sensitive lipase and lipoprotein lipase in human adipose tissue in vivo: implications for the control of fat storage and fat mobilization. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 35: 163–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goulbourne C. N., Gin P., Tatar A., Nobumori C., Hoenger A., Jiang H., Grovenor C. R., Adeyo O., Esko J. D., Goldberg I. J., et al. 2014. The GPIHBP1-LPL complex is responsible for the margination of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in capillaries. Cell Metab. 19: 849–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young S. G., Davies B. S., Fong L. G., Gin P., Weinstein M. M., Bensadoun A., Beigneux A. P. 2007. GPIHBP1: an endothelial cell molecule important for the lipolytic processing of chylomicrons. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 18: 389–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinstock P. H., Bisgaier C. L., Aalto-Setala K., Radner H., Ramakrishnan R., Levak-Frank S., Essenburg A. D., Zechner R., Breslow J. L. 1995. Severe hypertriglyceridemia, reduced high density lipoprotein, and neonatal death in lipoprotein lipase knockout mice. Mild hypertriglyceridemia with impaired very low density lipoprotein clearance in heterozygotes. J. Clin. Invest. 96: 2555–2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sattler W., Levak-Frank S., Radner H., Kostner G. M., Zechner R. 1996. Muscle-specific overexpression of lipoprotein lipase in transgenic mice results in increased alpha-tocopherol levels in skeletal muscle. Biochem. J. 318: 15–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levak-Frank S., Hofmann W., Weinstock P. H., Radner H., Sattler W., Breslow J. L., Zechner R. 1999. Induced mutant mouse lines that express lipoprotein lipase in cardiac muscle, but not in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, have normal plasma triglyceride and high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96: 3165–3170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levak-Frank S., Radner H., Walsh A., Stollberger R., Knipping G., Hoefler G., Sattler W., Weinstock P. H., Breslow J. L., Zechner R. 1995. Muscle-specific overexpression of lipoprotein lipase causes a severe myopathy characterized by proliferation of mitochondria and peroxisomes in transgenic mice. J. Clin. Invest. 96: 976–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zechner R. 1997. The tissue-specific expression of lipoprotein lipase: implications for energy and lipoprotein metabolism. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 8: 77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoefler G., Noehammer C., Levak-Frank S., el-Shabrawi Y., Schauer S., Zechner R., Radner H. 1997. Muscle-specific overexpression of human lipoprotein lipase in mice causes increased intracellular free fatty acids and induction of peroxisomal enzymes. Biochimie. 79: 163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cryer A., Riley S. E., Williams E. R., Robinson D. S. 1976. Effect of nutritional status on rat adipose tissue, muscle and post-heparin plasma clearing factor lipase activities: their relationship to triglyceride fatty acid uptake by fat-cells and to plasma insulin concentrations. Clin. Sci. Mol. Med. 50: 213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross A. C., Pasatiempo A. M., Green M. H. 2004. Chylomicron margination, lipolysis, and vitamin A uptake in the lactating rat mammary gland: implications for milk retinoid content. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood). 229: 46–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merkel M., Kako Y., Radner H., Cho I. S., Ramasamy R., Brunzell J. D., Goldberg I. J., Breslow J. L. 1998. Catalytically inactive lipoprotein lipase expression in muscle of transgenic mice increases very low density lipoprotein uptake: direct evidence that lipoprotein lipase bridging occurs in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95: 13841–13846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson D. S., Jennings M. A. 1965. Release of clearing factor lipase by the perfused rat heart. J. Lipid Res. 6: 222–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ben-Zeev O., Schwalb H., Schotz M. C. 1981. Heparin-releasable and nonreleasable lipoprotein lipase in the perfused rat heart. J. Biol. Chem. 256: 10550–10554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu G., Olivecrona T. 1992. Synthesis and transport of lipoprotein lipase in perfused guinea pig hearts. Am. J. Physiol. 263: H438–H446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu G., Zhang L., Gupta J., Olivecrona G., Olivecrona T. 2007. A transcription-dependent mechanism, akin to that in adipose tissue, modulates lipoprotein lipase activity in rat heart. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 293: E908–E915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olafsen T., Young S. G., Davies B. S., Beigneux A. P., Kenanova V. E., Voss C., Young G., Wong K. P., Barnes R. H., 2nd, Tu Y., et al. 2010. Unexpected expression pattern for glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored HDL-binding protein 1 (GPIHBP1) in mouse tissues revealed by positron emission tomography scanning. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 39239–39248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tornvall P., Olivecrona G., Karpe F., Hamsten A., Olivecrona T. 1995. Lipoprotein lipase mass and activity in plasma and their increase after heparin are separate parameters with different relations to plasma lipoproteins. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 15: 1086–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karpe F., Olivecrona T., Olivecrona G., Samra J. S., Summers L. K., Humphreys S. M., Frayn K. N. 1998. Lipoprotein lipase transport in plasma: role of muscle and adipose tissues in regulation of plasma lipoprotein lipase concentrations. J. Lipid Res. 39: 2387–2393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu G., Olivecrona G., Olivecrona T. 2003. The distribution of lipoprotein lipase in rat adipose tissue. Changes with nutritional state engage the extracellular enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 11925–11930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scow R. O., Chernick S. S., Fleck T. R. 1977. Lipoprotein lipase and uptake of triacylglycerol, cholesterol and phosphatidylcholine from chylomicrons by mammary and adipose tissue of lactating rats in vivo. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 487: 297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karpe F., Olivecrona T., Walldius G., Hamsten A. 1992. Lipoprotein lipase in plasma after an oral fat load: relation to free fatty acids. J. Lipid Res. 33: 975–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frayn K. N., Shadid S., Hamlani R., Humphreys S. M., Clark M. L., Fielding B. A., Boland O., Coppack S. W. 1994. Regulation of fatty acid movement in human adipose tissue in the postabsorptive-to-postprandial transition. Am. J. Physiol. 266: E308–E317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hultin M., Savonen R., Chevreuil O., Olivecrona T. 2013. Chylomicron metabolism in rats: kinetic modeling indicates that the particles remain at endothelial sites for minutes. J. Lipid Res. 54: 2595–2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blanchette-Mackie E. J., Masuno H., Dwyer N. K., Olivecrona T., Scow R. O. 1989. Lipoprotein lipase in myocytes and capillary endothelium of heart: immunocytochemical study. Am. J. Physiol. 256: E818–E828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bragdon J. H., Gordon R. S., Jr 1958. Tissue distribution of C14 after the intravenous injection of labeled chylomicrons and unesterified fatty acids in the rat. J. Clin. Invest. 37: 574–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fielding C. J., Renston J. P., Fielding P. E. 1978. Metabolism of cholesterol-enriched chylomicrons. Catabolism of triglyceride by lipoprotein lipase of perfused heart and adipose tissues. J. Lipid Res. 19: 705–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stein O., Halperin G., Leitersdorf E., Olivecrona T., Stein Y. 1984. Lipoprotein lipase mediated uptake of non-degradable ether analogues of phosphatidylcholine and cholesteryl ester by cultured cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 795: 47–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bartelt A., Bruns O. T., Reimer R., Hohenberg H., Ittrich H., Peldschus K., Kaul M. G., Tromsdorf U. I., Weller H., Waurisch C., et al. 2011. Brown adipose tissue activity controls triglyceride clearance. Nat. Med. 17: 200–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khedoe P. P., Hoeke G., Kooijman S., Dijk W., Buijs J. T., Kersten S., Havekes L. M., Hiemstra P. S., Berbee J. F., Boon M. R., et al. 2015. Brown adipose tissue takes up plasma triglycerides mostly after lipolysis. J. Lipid Res. 56: 51–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]