Abstract

Background: Studies have noted immunological disruptions in patients with tic disorders, including increased serum cytokine levels. This study aimed to determine whether or not cytokine levels could be correlated with tic symptom severity in patients with a diagnosed tic disorder.

Methods: Twenty-one patients, ages 4–17 years (average 10.63±2.34 years, 13 males), with a clinical diagnosis of Tourette's syndrome (TS) or chronic tic disorder (CTD), were selected based on having clinic visits that coincided with a tic symptom exacerbation and a remission. Ratings of tic severity were assessed using the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) and serum cytokine levels (interleukin [IL]-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-13, interferon [IFN]-γ, tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α, and granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor [GM-CSF]) were measured using Luminex xMAP technology.

Results: During tic symptom exacerbation, patients had higher median serum TNF-α levels (z=−1.962, p=0.05), particularly those on antipsychotics (U=9.00, p=0.033). Increased IL-13 was also associated with antipsychotic use during exacerbation (U=4.00, p=0.043) despite being negatively correlated to tic severity scores (ρ=−0.599, p=018), whereas increased IL-5 was associated with antibiotic use (U=6.5, p=0.035). During tic symptom remission, increased serum IL-4 levels were associated with antipsychotic (U=6.00, p=0.047) and antibiotic (U=1.00, p=0.016) use, whereas increased IL-12p70 (U=4.00, p=0.037) was associated with antibiotic use.

Conclusions: These findings suggest a role for cytokine dysregulation in the pathogenesis of tic disorders. It also points toward the mechanistic involvement and potential diagnostic utility of cytokine monitoring, particularly TNF-α levels. Larger, systematic studies are necessary to further delineate the role of cytokines and medication influences on immunological profiling in tic disorders.

Introduction

Tic disorders have been shown to have a strong genetic component, with observations of common polymorphisms and a high degree of hereditability among patients (Chou et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2011). These polymorphisms, although they are potential diagnostic markers, do not fully explain the pathological mechanism, the heterogeneous symptoms, or the unpredictable course characterized by periods of symptom waxing and waning that is seen in patients with tic disorders. Similarly, evidence of neurochemical abnormalities in dopamine, serotonin, and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) systems, although an important component of the mechanism of tic disorders and related to aspects of motor dysfunction, does not fully explain the etiology of tic disorders (Jijun et al. 2010; Lerner et al. 2012). The infectious etiology of neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders has gained increasing attention as a result of observations correlating prenatal and early childhood infections (Brown et al. 2004; Winter et al. 2009; Khandaker et al. 2014) and immunological abnormalities (Ashwood et al. 2011) to the occurrence of schizophrenia and autism.

Despite rekindled interest, however, infection and immunological dysfunction have long been hypothesized as central components of tic disorders, partly as a result of observations of infection-triggered symptomology, cytokine and other immune abnormalities, and strong similarities to Sydenham's chorea (SC), the prototype infection-triggered neurological disorder (Swedo 1994). Cytokines in particular have been shown to be an important part of the pathological mechanism of these disorders, with increasing evidence of genetic polymorphisms and abnormal serum expression being associated with disease course (Leckman et al. 2005; Chou et al. 2010). In SC, a group A streptococcal (GAS) mediated disorder occurring in a subset of individuals with rheumatic fever (RF), patients experience involuntary movements and a manifestation of neuropsychiatric symptoms including obsessions/compulsions and anxiety, which are thought to be the result antistreptococcal antibodies targeting structures in the basal ganglia, dopamine receptors, and neuronal proteins (Kirvan et al. 2003; Dale et al. 2012; Ben-Pazi et al. 2013). There has also been increasing evidence to support an equally important role for cytokines in disease pathology, given observations of increased serum cytokine levels in patients with cytokine-related neuropathology in similar movement disorders (Church et al. 2003; Lewitus et al. 2014). These pathologies, particularly increases in serum cytokine levels, have also been observed in patients with tic disorders, along with abnormal immunological responses to GAS and basal ganglia pathologies (Giedd et al. 2000; Kalanithi et al. 2005; Bombaci et al. 2009).

Given the increasing awareness of the role of immune dysregulation in tic disorders, we aimed to determine if serum cytokine levels differed during periods of tic symptom exacerbation and remission in patients with a diagnosis of chronic tic disorder (CTD) or Tourette syndrome (TS). We hypothesized that inflammatory cytokine levels would be positively correlated with tic symptom severity. Understanding the role of these cytokines in tic pathology may be an important step in understanding the mechanism of tic disorders and the involvement of the immune system.

Methods

Participants

Twenty-one patients with CTD or TS, ages 4–17 years, were selected from a larger prospective cohort recruited to investigate neuropsychiatric phenomena with temporal association to streptococcal pharyngitis (Murphy et al. 2012). Briefly, participants were selected for the current study based on meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. (text revision) (American Psychiatric Association 2000) criteria for a tic disorder (TS or CTD) confirmed by clinical interview and a semistructured diagnostic interview with a trained clinician. Participants with active psychosis, mania, current suicidal intent, a diagnosis of intellectual deficiency, or autism (based on clinical interview with a trained clinician) were excluded from the study. Those on stable doses of psychotropic medications were not excluded. Participants were also required to have a documented exacerbation/flare and a remission episode of tic symptoms during the course of the larger cohort study, to be included in the present study. The average time between an exacerbation and remission cycle was 8.7 months. Study procedures were approved by the institutional review board, and parental consent and participant assent when applicable (>7 years) was obtained prior to enrollment.

Clinical assessments

Assessments were conducted by T.K.M. or by a trained clinician with experience in pediatric tic disorders, and consisted of comprehensive parent, child, and clinical ratings for tic disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), as well as comprehensive neurological/physical examinations and medical record reviews. Assessments included the clinician-rated Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) for tic disorders (Leckman et al. 1989), and the clinician rated Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS) for OCD (Scahill et al. 1997). For the present study, tic symptoms were considered to be in an exacerbated state when the current visit's YGTSS Total Severity Score was ≥15 points, and exceeded the previous visit's score by ≥5 points. Similarly, OCD symptoms were considered to be in an exacerbated state when the current visit's CY-BOCS Total Score was ≥15 points and exceeded the previous visit's score by ≥5 points. For remission, tic or OCD symptoms were considered remitted if the current visit's YGTSS or CYBOCS score was <5.

Cytokine analysis

In addition to the clinical assessments, serum samples were collected during visits coinciding with an exacerbation of tic symptoms, and again during a visit coinciding to symptom remission. In short, peripheral blood was collected in silicone-coated tubes (BD Bioscience, CA), centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 15 minutes and serum collected, aliquoted, and stored at −80 until analysis. Serum levels of cytokines were measured using human multiplexing bead immunoassays and Luminex-xMAP fluorescent bead-based technology. The standard curve was derived using Bio-Plex software and manufacturer-supplied reference cytokine levels, and a five parameter model used to calculate final concentration. Nine cytokines (interleukin [IL]-2), IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-13, interferon (IFN)-γ), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) were measured per manufacturer's instructions (BioRad, CA).

Statistical analysis

The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to evaluate differences in serum cytokine levels during periods of symptom exacerbation and remission. Mann–Whitney test was used to determine between-group differences in patients presenting with exacerbation–remission of only their tic symptoms, and those who experienced exacerbation–remission of OCD/tic symptoms. Data were reported as medians unless otherwise specified. Spearman rank correlation coefficients were used to test for associations between cytokine levels and symptom severity. SPSS statistical software was used to analyze all data with an α of 0.05 defining statistical significance.

Results

Participant demographics and clinical characteristics

Four participants with CTD (n=4) and 17 with TS (n=17) were selected for this study (mean age=10.63±2.34 years, 62% male). The average age of tic onset was 6.56±2.54 years, and average duration of symptoms was 3.02±2.09 years. During periods of tic symptom exacerbation, average YGTSS Total Tic Severity scores were 23.81±7.20 compared with 0.62±1.56 during tic symptom remission. Ninety percent of patients also presented with comorbid OCD (n=19), with an average age of OCD onset of 6.95±2.57 years and an average duration of 2.89±2.21 years. For those with comorbid OCD, the average CY-BOCS score during periods of tic symptom exacerbation was 17.37±10.77, compared with 11.42±10.69 during periods of tic remission (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients Based on Tic/OCD Symptom Comorbidity During Symptom Exacerbation and Remission

| Tic only (n=10) | OCD/tic (n=11) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 8 (80.0) | 5 (62.5) |

| Age, mean±SD | 10.67±2.39 | 10.58±2.41 |

| YGTSS ex,a±SD | 23.50±7.41 | 24.09±7.35 |

| YGTSS rem,b±SD | 0.90±1.91 | 0.36±1.21 |

| Age onset | 5.88±2.33 | 7.18±2.68 |

| Duration | 3.49±2.35 | 2.59±1.83 |

| CY-BOCS ex,a±SD | 6.75±5.75 | 25.09±5.45 |

| CY-BOCS rem,b±SD | 7.75±7.36 | 14.09±12.21 |

| Age onset | 7.13±2.18 | 6.82±2.93 |

| Duration | 2.71±2.17 | 3.01±2.35 |

| Combined ex,a±SD | 14.45±5.62 | 24.59±4.75 |

| Combined rem,b±SD | 3.55±3.32 | 7.23±6.31 |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| PANDAS | 1 (10.0) | 4 (36.4) |

| ADHD | 5 (50.0) | 5 (45.5) |

| OCD/tics | 8 (80.0) | 11 (100.0) |

| Tics only | 2 (20.0) | 0 (0) |

| Medications, ex/rem | ||

| Antipsychotics | 5/4 | 10/9 |

| Antibiotics | 1/0 | 2/4 |

| Other | 9/9 | 11/10 |

Data represent patients experiencing an exacerbation–remission cycle of their tic symptoms only, “tic only,” and those experiencing an exacerbation and/or remission cycle of both OCD and tic symptoms, “OCD/tics.”

exa, exacerbation (ascores taken during a period of tic and OCD symptom exacerbation); remb, remission (bscores taken during a period of tic and OCD symptom remission); YGTSS, Yale Global Tic Severity Scale; CY-BOCS, Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale; OCD, obsessive compulsive disorder; PANDAS, pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcus; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Do serum cytokine levels differ during periods of tic symptom exacerbation and remission?

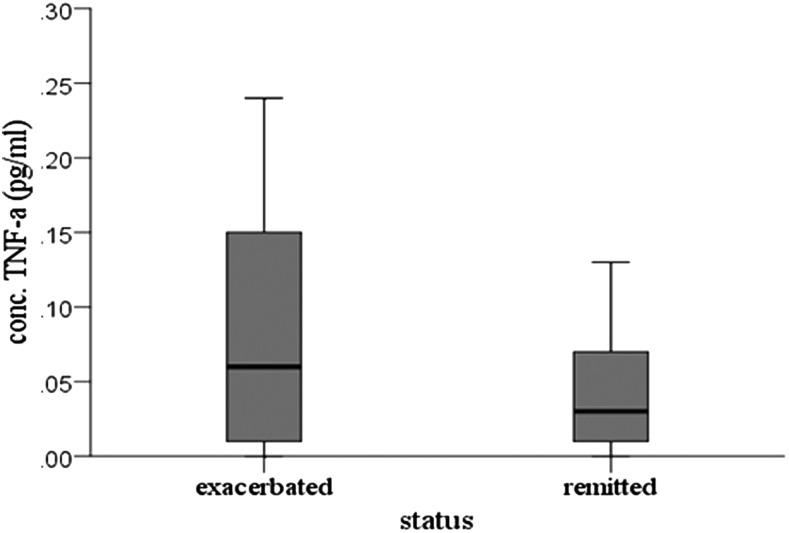

The level of nine cytokines was analyzed in the serum of patients with a clinical diagnosis of CTD or TS when their tic symptoms were in an exacerbated or flared state, and again when they had remitted, irrespective of OCD symptom status (Table 2). Of the 13 patients having detectable serum TNF-α levels, 77% (n=10) showed higher plasma concentrations of TNF-α during periods of tic symptom exacerbation whereas 15% (n=2) had a higher serum concentration during tic symptom remission. One patient showed no change in TNF-α expression. Patients experiencing an exacerbation of their tic symptoms showed a significant increase in serum TNF-α levels compared with those experiencing a tic symptom remission (Z=−1.962, p=0.05), as median serum TNF-α was 0.06 during periods of exacerbation and 0.03 during periods of remission (Fig. 1). No other significant differences in serum cytokine levels were observed.

Table 2.

Serum Cytokine Levels During Tic Symptom Exacerbation and Remission

| Cytokines | Exacerbation | Remission | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-4 | 0.07 (0.00–1.59) | 0.05 (0.01–1.67) | −0.04 | 0.97 |

| IL-5 | 0.79 (0.00–0.58) | 0.59 (0.03–1.88) | −0.05 | 0.96 |

| IL-10 | 2.76 (0.32–3.02) | 1.73 (0.00–20.64) | −0.07 | 0.94 |

| IL-12p70 | 28.20 (0.10–1.47) | 0.00, (0.08–2.32) | −0.87 | 0.38 |

| IL-13 | 0.81 (0.15–6.76) | 0.45 (0.15–7.49) | −0.22 | 0.83 |

| IFN-γ | 15.53 (0.88–48.75) | 12.35 (2.16–51.51) | −1.29 | 0.20 |

| TNF-α | 0.06 (0.00–0.60) | 0.03 (0.00–0.34) | −1.96 | 0.05* |

Data represent results of the Wilcoxon sign rank test. Cytokine levels are measured in pg/mL and are expressed as medians and ranges. Levels for IL-2 and GMC-SF were below lowest detectable limit.

IL, interleukin; IFN, interferon; TFN, tumor necrosis factor; GMC-SF, granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor.

Statistically significant result.

FIG. 1.

Serum level of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α during tic symptom exacerbation and remission.

Does OCD comorbidity impact the level of serum cytokines during a tic exacerbation–remission cycle?

We also examined whether cytokine levels during periods of tic symptom exacerbation and remittance differed in patients experiencing an exacerbation–remission cycle of only their tic symptoms, (tic only), compared with those experiencing an exacerbation–remission cycle of both OCD and tic symptoms (OCD/tics). Of the 19 patients presenting with a diagnosis of comorbid OCD and tics, 11 experienced an exacerbation and subsequent remission of both OCD and tic symptoms (Table 1). There were no significant differences in serum cytokine levels between tic only patients and OCD/tic patients. We also examined differences in patients presenting with a CTD versus those presenting with TS. Again we found no significant differences between these two groups, nor did we find any significant differences associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS) comorbidity.

Does medication status affect cytokine level?

All patients enrolled in this study were receiving some form of medication, either prescribed or over the counter, during periods of tic symptom exacerbation and remission. Seventy-one percent of patients were receiving an antipsychotic medication, and 14% were receiving an antibiotic. Ninety-five percent were receiving an over the counter medication during periods of tic symptom exacerbation whereas 91% received similar medications during symptom remission (Table 1). We examined the effect of medication use on serum cytokine levels during periods of tic exacerbation and remission. During periods of tic symptom exacerbation, median serum cytokine level for TNF-α (U=9.00, p=0.033) and IL-13 (U=4.00, p=0.043) were significantly elevated in patients taking antipsychotics, whereas IL-5 (U=6.5, p=0.035) was significantly elevated in those taking antibiotics (Table 3). During periods of symptom remission, median IL-4 was significantly elevated in those taking antipsychotics (U=6.00, p=0.047) and antibiotics (U=1.00, p=0.016), whereas IL12p70 was significantly elevated in those taking antibiotics (U=4.00, p=0.037) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Impact of Medications on Cytokine Expression During Tic Symptom Exacerbation

| Cytokine | Statistics | IL-4 | IL-5 | IL-10 | IL-12p70 | IL-13 | IFN-γ | TNF-α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antipsychotic | Yes | 6.40 | 12.23 | 9.31 | 8.31 | 9.17 | 7.90 | 10.18 |

| No | 2.00 | 7.92 | 8.00 | 6.00 | 3.33 | 8.80 | 4.80 | |

| U | 1.00 | 26.50 | 22.00 | 9.00 | 4.00 | 21.00 | 9.00 | |

| p | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.04* | 0.62 | 0.03* | |

| Antibiotic | Yes | 5.50 | 17.83 | 5.67 | 11.33 | 5.67 | 8.00 | 8.50 |

| No | 6.19 | 9.86 | 9.71 | 7.17 | 8.58 | 8.00 | 8.50 | |

| U | 10.50 | 6.50 | 11.00 | 8.00 | 11.00 | 7.00 | 14.00 | |

| p | 0.76 | 0.04* | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.31 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Data represent results of the Mann–Whitney U Test. Cytokine levels are measured in pg/mL and are expressed as medians. Levels for IL-2 and GMC-SF were below lowest detectable limit.

IL, interleukin; IFN, interferon; TFN, tumor necrosis factor; GMC-SF, granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor.

Statistically significant result.

Table 4.

Impact of Medications on Cytokine Level During Tic Symptom Remission

| Cytokine | Statistic | IL-4 | IL-5 | IL-10 | IL-12p70 | IL-13 | IFN-γ | TNF-α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antipsychotic | Yes | 8.90 | 11.93 | 10.57 | 8.58 | 9.23 | 8.31 | 7.62 |

| no | 4.00 | 8.67 | 8.40 | 8.25 | 5.33 | 6.42 | 6.00 | |

| U | 6.00 | 31.00 | 27.00 | 23.00 | 10.00 | 17.50 | 5.00 | |

| p | 0.05* | 0.27 | 0.46 | 0.90 | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.71 | |

| Antibiotic | Yes | 12.67 | 15.67 | 15.00 | 13.67 | 11.67 | 8.00 | 8.17 |

| no | 6.09 | 10.22 | 9.06 | 7.31 | 7.77 | 7.42 | 7.32 | |

| U | 1.00 | 13.00 | 9.00 | 4.00 | 10.00 | 11.00 | 14.50 | |

| p | 0.02* | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.04* | 0.20 | 0.86 | 0.75 |

Data represent results of the Mann–Whitney U Test. Cytokine levels are measured in pg/mL and are expressed as medians. Levels for IL-2 and GMC-SF were below lowest detectable limit.

IL, interleukin; IFN, interferon; TFN, tumor necrosis factor; GMC-SF, granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor.

Statistically significant result.

Does symptom severity, as measured by the YGTSS and CY-BOCS correlate with cytokine level?

We examined whether there was a correlation between symptom severity, as reflected by the YGTSS Total Severity and CY-BOCS Total scores, and serum cytokine level. During periods of tic symptom exacerbation, serum levels of IL-13 showed a moderate negative correlation to YGTSS Total Severity scores (ρ=−0.599, p=0.018), particularly symptoms of motor tics (ρ=−0.655, p=0.008). However, this correlation was not observed during symptom remission. There were no significant correlations observed between serum cytokine levels and CY-BOCS scores.

Discussion

Several studies have found evidence suggesting immune abnormalities in patients with tic disorders, supporting the hypothesis that infection and abnormal immunological responses to infection may be central to the underlying pathological mechanism of tic disorders. In the present study, we sought to examine the relationship between serum cytokine levels and tic symptom severity in patients with a clinical diagnosis of CTD or TS. Seventy-seven percent of patients expressed significantly higher levels of serum TNF-α during periods of tic symptom exacerbation, corroborating similar findings of associations between tic symptom severity and increases in serum TNF-α levels (Leckman et al. 2005). These observations may suggest an important role for this cytokine in the pathogenesis of tic disorders, while providing an important diagnostic tool.

TNF-α, a proinflammatory cytokine, plays an integral role in immunological responses to infection, as a potent regulator of the immune system and inflammatory processes, recruiting macrophages, activating T-cells, and inducing the expression of downstream cytokines and other immune mediators during infection (Kuhweide et al. 1990; Kim et al. 2006). Like many other cytokines, TNF-α also plays an equally important role in the regulation of the central nervous system (CNS), both physiological and pathological. Recent studies in neurodegenerative disorders such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) have highlighted the pathological aspects of this relationship, showing evidence of increased serum TNF-α levels preceding clinical presentations of motor dysfunction (Tolosa et al. 2011). Although the exact mechanism is still unknown, oxidative stress and resultant motor neuron cell death, which are the consequences of neuroinflammation, have been proposed. However, several studies have pointed toward excitotoxicity from TNF-α induced modulation of glutamate signaling as well as GABA and glutamate receptors expression (Lewitus et al. 2014; Olmos and Llado 2014). The actions of TNF-α in ALS may shed light on its role in tic disorders given the comparable clinical observations, including the association of increased TNF-α levels and symptom severity and the involvement of the GABA systems (Jijun et al. 2010; Lerner et al. 2012).

Although there appears to be a significant role for TNF-α in tic disorders, other cytokines such as IL-13 may also be important in understanding the underlying role of the immune system in this disorder. IL-13, which we found to be negatively correlated to tic symptom severity, displays anti-inflammatory properties, and has been shown to regulate immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibody production, which has also been shown to correlate negatively with YGTSS scores (Hoshino et al. 1999; Wynn 2003; Hajoui et al. 2004). The role of IL-13 in tic disorders may be less characterized; however, its role in immune regulation and its correlation with autoimmune disorders suggest that it may be a promising target along with TNF-α for explaining the mechanism of tic disorders. Moreover, IL-13 and TNF-α have been shown to display bidirectional regulation with IL-13 downregulating the expression of TNF-α and TNF-α potentially downregulating IL-13 (Cosentino et al. 1995; Albanesi et al. 2007). With increasing evidence of a role for immune dysregulation in the pathogenesis of tic disorders, cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-13 may be an important link in understanding the pathological mechanism driving this disorder.

In addition to explaining aspects of disease mechanism, the ability to correlate cytokine levels to disease state and symptom severity may be an important diagnostic asset, particularly in a pediatric setting where significant emphasis must be placed on parental recall because of a lack of biological markers. Although only TNF-α and IL-13 showed significant associations with tic severity in our study, with TNF-α being increased during exacerbations and IL-13 correlating negatively to severity scores, we observed increases in the level of several other cytokines in patients receiving antibiotic/antipsychotic medications. TNF-α and IL-13 levels were increased during tic symptom exacerbation in patients taking antipsychotics, whereas IL-5 was increased in patients taking antibiotics. We also observed increased levels of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-4 in patients on antibiotic and/or antipsychotic medications during tic symptom remission.

These observations suggest that cytokine levels may be impacted by medication status, as antipsychotics and antibiotics have been shown to have immune modulating effects, with studies showing increased IL-4 levels following antipsychotic treatment and decreased TNF-α levels with macrolides (Morikawa et al. 2002; Himmerich et al. 2011; Al-Amin et al. 2013). The impact of antipsychotic drugs on the immune system and cytokine expression may highlight a potentially important aspect of their therapeutic mechanism. With increasing evidence of the immune irregularities, including cytokine disruption, in neurological disorders such as tic disorders, the ability of antipsychotics to modulate cytokine expression and potentially normalize the immune system may be, at least in part, key to their therapeutic efficacy (Al-Amin et al. 2013). In the case of antibiotics, their impact on the immune system has been well documented and may be indirectly related to their mechanism of action (Morikawa et al. 2002; Williams et al. 2005). It is important to remember, however, that these interactions may not be therapeutically beneficial, as seen from the more deleterious side effects attributable to antipsychotic and antibiotic use. Particularly in the case of antibiotics, the inability of these agents to differentiate between resident gastrointestinal microbial constituents, known to participate in immune regulation, and invading pathogenic species, can result in modulation of the immune system, with little therapeutic value (Jakobsson et al. 2010).

It is also noteworthy to remember that these observations may not be causative, as patients experiencing a more severe symptom exacerbation are more likely to require pharmacological intervention. Conversely, the association with increased cytokine levels during antibiotic or antipsychotic treatment may be coincidental, with increases in proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, and anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4 correlating to changes in tic severity. Regardless, this association is one that requires further investigation.

Conclusion

Despite our findings, some disagreement still exists among studies investigating immune irregularities, particularly cytokine levels, within the tic population. Some groups, for example, have noted no correlations between TNF-α level and tic disorder (Gabbay et al. 2009), whereas others have found reduced levels of TNF-α level in patients with tic disorders (Matzt et al. 2012). These discrepancies may be the result of methodological differences in study design, including inherent differences within the patient populations chosen for each study. Although in most studies patients were enrolled based on a diagnosis of a tic disorder, the presence of comorbid disorders and differences in criteria for defining flared versus remitted states may lead to differences in study outcomes. Psychotropic and antibiotic medications pose another confounding factor, although other studies reported no significant effects of medications, despite both of these medication categories having been shown to modulate cytokine level (Obregon et al. 2012). However, the mounting evidence supports that cytokine measurement may be an important clinical tool in determining susceptibility, diagnosis, symptom monitoring, and, perhaps, therapeutic intervention, and more work is necessary to determine the exact role of cytokines in tic etiology.

Limitations

Although this study supports the hypothesis of an infection and/or immune-mediated etiology of tic disorders, there were several limitations that further necessitate the need for larger systematic analyses of immune function in tic disorders. These included a limited sample size, the presence of comorbid disorders within our cohort, and a significant percentage of patients on psychotropic and antibiotic medications, which are known to have immunological effects.

Clinical Significance

Despite the limitations, this study supports previous findings by other groups citing cytokine dysregulation in patients with tic disorders. Furthermore, it identifies TNF-α as an important target for investigating cytokine dysregulation and immunological abnormalities within the tic population. Understanding the role of immune abnormalities in the pathogenesis of tic disorders may not only aid in our understanding the mechanism driving this disorder but may also provide biological markers that can be utilized clinically in diagnosis, the determination of symptom severity, and therapeutic intervention.

Disclosures

Dr. Tanya Murphy has received research support in the past 3 years from the All Children's Hospital Research Foundation, AstraZeneca Neuroscience iMED, Centers for Disease Control, International OCD Foundation (IOCDF), the National Institutes of Health, Otsuka, Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, Roche Pharmaceuticals, Shire, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Tourette Syndrome Association. She is also on the Scientific Advisory Board for IOCDF. She receives a textbook honorarium from Lawrence Erlbaum. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- Al-Amin MM, Nasir Uddin MM, Mahmud Reza H: Effects of antipsychotics on the inflammatory response system of patients with schizophrenia in peripheral blood mononuclear cell cultures. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci 11:144–151, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albanesi C, Fairchild HR, Madonna S, Scarponi C, De Pita O, Leung DY, Howell MD: IL-4 and IL-13 negatively regulate TNF-alpha- and IFN-gamma-induced beta-defensin expression through STAT-6, suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS)-1, and SOCS-3. J Immunol 179:984–992, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. (Text Revision). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Ashwood P, Krakowiak P, Hertz–Picciotto I, Hansen R, Pessah I, Van de Water J: Elevated plasma cytokines in autism spectrum disorders provide evidence of immune dysfunction and are associated with impaired behavioral outcome. Brain Behav Immun 25:40–45, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Pazi H, Stoner JA, Cunningham MW: Dopamine receptor autoantibodies correlate with symptoms in Sydenham's chorea. PLoS One. 8:e73516, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombaci M, Grifantini R, Mora M, Reguzzi V, Petracca R, Meoni E, Balloni S, Zingaretti C, Falugi F, Manetti AG, Margarit I, Musser JM, Cardona F, Orefici G, Grandi G, Bensi G: Protein array profiling of tic patient sera reveals a broad range and enhanced immune response against Group A Streptococcus antigens. PLoS One. 4:e6332, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AS, Begg MD, Gravenstein S, Schaefer CA, Wyatt RJ, Bresnahan M, Babulas VP, Susser ES: Serologic evidence of prenatal influenza in the etiology of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 61:774–780, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou IC, Lin HC, Wang CH, Lin WD, Lee CC, Tsai CH, Tsai FJ: Polymorphisms of interleukin 1 gene IL1RN are associated with Tourette syndrome. Pediatr Neurol 42:320–324, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church AJ, Dale RC, Cardoso F, Candler PM, Chapman MD, Allen ML, Klein NJ, Lees AJ, Giovannoni G: CSF and serum immune parameters in Sydenham's chorea: Evidence of an autoimmune syndrome? J Neuroimmunol 136:149–153, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino G, Soprana E, Thienes CP, Siccardi AG, Viale G, Vercelli D: IL–13 down-regulates CD14 expression and TNF-alpha secretion in normal human monocytes. J Immunol 155:3145–3151, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale RC, Merheb V, Pillai S, Wang D, Cantrill L, Murphy TK, Ben–Pazi H, Varadkar S, Aumann TD, Horne MK, Church AJ, Fath T, Brilot F: Antibodies to surface dopamine-2 receptor in autoimmune movement and psychiatric disorders. Brain 135:3453–3468, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay V, Coffey BJ, Guttman LE, Gottlieb L, Katz Y, Babb JS, Hamamoto MM, Gonzalez CJ: A cytokine study in children and adolescents with Tourette's disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 33:967–971, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd JN, Rapoport JL, Garvey MA, Perlmutter S, Swedo SE: MRI assessment of children with obsessive-compulsive disorder or tics associated with streptococcal infection. Am J Psychiatry 157:281–283, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajoui O, Janani R, Tulic M, Joubert P, Ronis T, Hamid Q, Zheng H, Mazer BD: Synthesis of IL-13 by human B lymphocytes: regulation and role in IgE production. J Allergy Clin Immunol 114:657–663, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmerich H, Schonherr J, Fulda S, Sheldrick AJ, Bauer K, Sack U: Impact of antipsychotics on cytokine production in-vitro. J Psychiatr Res 45:1358–1365, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino T, Winkler–Pickett RT, Mason AT, Ortaldo JR, Young HA: IL-13 production by NK cells: IL-13-producing NK and T cells are present in vivo in the absence of IFN-gamma. J Immunol 162:51–59, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson HE, Jernberg C, Andersson AF, Sjolund–Karlsson M, Jansson JK, Engstrand L: Short-term antibiotic treatment has differing long-term impacts on the human throat and gut microbiome. PLoS One 5:e9836, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jijun L, Zaiwang L, Anyuan L, Shuzhen W, Fanghua Q, Lin Z, Hong L: Abnormal expression of dopamine and serotonin transporters associated with the pathophysiologic mechanism of Tourette syndrome. Neurol India 58:523–529, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalanithi PS, Zheng W, Kataoka Y, DiFiglia M, Grantz H, Saper CB, Schwartz ML, Leckman JF, Vaccarino FM: Altered parvalbumin-positive neuron distribution in basal ganglia of individuals with Tourette syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:13,307–13,312, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandaker GM, Stochl J, Zammit S, Lewis G, Jones PB: Childhood Epstein–Barr virus infection and subsequent risk of psychotic experiences in adolescence: A population-based prospective serological study. Schizophr Res 158:19–24, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EY, Priatel JJ, Teh SJ, Teh HS: TNF receptor type 2 (p75) functions as a costimulator for antigen-driven T cell responses in vivo. J Immunol 176:1026–1035, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirvan CA, Swedo SE, Heuser JS, Cunningham MW: Mimicry and autoantibody-mediated neuronal cell signaling in Sydenham chorea. Nat Med 9:914–920, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhweide R, Van Damme J, Ceuppens JL: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin 6 synergistically induce T cell growth. Eur J Immunol 20:1019–1025, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckman JF, Katsovich L, Kawikova I, Lin H, Zhang H, Kronig H, Morshed S, Parveen S, Grantz H, Lombroso PJ, King RA: Increased serum levels of interleukin-12 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in Tourette's syndrome. Biol Psychiatry 57:667–673, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckman JF, Riddle MA, Hardin MT, Ort SI, Swartz KL, Stevenson J, Cohen DJ: The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale: Initial testing of a clinician-rated scale of tic severity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 28:566–573, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner A, Bagic A, Simmons JM, Mari Z, Bonne O, Xu B, Kazuba D, Herscovitch P, Carson RE, Murphy DL, Drevets WC, Hallett M: Widespread abnormality of the gamma-aminobutyric acid-ergic system in Tourette syndrome. Brain 135:1926–1936, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewitus GM, Pribiag H, Duseja R, St-Hilaire M, Stellwagen D: An adaptive role of TNFalpha in the regulation of striatal synapses. J Neurosci 34:6146–6155, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Yi M, Wang M, Sun Y, Che F, Ma X: Association of IL8 −251A/T, IL12B −1188A/C and TNF-alpha −238A/G polymorphisms with Tourette syndrome in a family-based association study in a Chinese Han population. Neurosci Lett 495:155–158, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matz J, Krause DL, Dehning S, Riedel M, Gruber R, Schwarz MJ, Muller N: Altered monocyte activation markers in Tourette's syndrome: a case-control study. BMC Psychiatry 12:29, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa K, Zhang J, Nonaka M, Morikawa S: Modulatory effect of macrolide antibiotics on the Th1- and Th2-type cytokine production. Int J Antimicrob Agents 19:53–59, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy TK, Storch EA, Lewin AB, Edge PJ, Goodman WK: Clinical factors associated with pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections. J Pediatr 160:314–319, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obregon D, Parker–Athill EC, Tan J, Murphy T: Psychotropic effects of antimicrobials and immune modulation by psychotropics: implications for neuroimmune disorders. Neuropsychiatry (London) 2:331–343, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmos G, Llado J: Tumor necrosis factor alpha: A link between neuroinflammation and excitotoxicity. Mediators Inflamm 2014:861231, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scahill L, Riddle MA, McSwiggin–Hardin M, Ort SI, King RA, Goodman WK, Cicchetti D, Leckman JF: Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: Reliability and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:844–852, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedo SE: Sydenham's chorea. A model for childhood autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders. JAMA 272:1788–1791, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolosa L, Caraballo–Miralles V, Olmos G, Llado J: TNF-alpha potentiates glutamate-induced spinal cord motoneuron death via NF-kappaB. Mol Cell Neurosci 46:176–186, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AC, Galley HF, Watt AM, Webster NR: Differential effects of three antibiotics on T helper cell cytokine expression. J Antimicrob Chemother 56:502–506, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter C, Djodari–Irani A, Sohr R, Morgenstern R, Feldon J, Juckel G, Meyer U: Prenatal immune activation leads to multiple changes in basal neurotransmitter levels in the adult brain: Implications for brain disorders of neurodevelopmental origin such as schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 12:513–524, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn TA: IL–13 effector functions. Annu Rev Immunol 21:425–456, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]