Abstract

The aim of this study was to describe the effectiveness of individualized dietary counseling in obese subjects based on narrative interview technique on the maintenance of body weight reduction, changes in dietary behaviors, including type of cooking and physical activity. One-hundred subjects out of four-hundred patients met the inclusion criteria. Individually, 45-minute educational program with motivation counseling was performed in 0, 6 and 12 weeks of the study. Patients were advised to follow individually well-balanced diet for 12 weeks. The individuals were asked about the changes in their dietary habits (Food Frequency Questionnaire). The mean percentage of body weight changes from the baseline were as follows: in 6th week- 5.9%, in 12th week - 10.9% and in 52th week - 9.7% (P < 0.0001), however there were no statistically significant changes while comparing body weight in 12th and 52th week. The maintenance of body weight reduction was connected with the dietary habits changes, mainly the type of cooking and increased consumption of vegetable oils. In conclusion, individualized dietary counseling, based on narrative interview technique is an effective intervention for obesity treatment that may help maintain body weight reduction and adapt the pro-healthy changes in type of cooking and sources of dietary fat.

Obesity presents multiple health challenges for healthcare systems. According to World Health Organization globally, in 2008 12% of adults aged over 20 were affected by obesity and 35% were overweight1. It is observed that approximately 70% will regain at least half of the weight lost within 2 years of successful weight loss attempts and will return to their baseline weight within 3–5 years2,3,4. Obese individuals lack the skills, motivation, and understanding how to approach the task effectively and safely5. The evidence linking food restriction and food craving is equivocal6. The challenge is to develop the weight management strategy for obese people that can be successful in sustaining initial weight loss7.

The education program conducted among obese subjects for proper dietary habits and healthy lifestyle, including regular physical activity, is an inseparable element of the therapeutic process, which should give long-term results8. The educating campaigns in the field of nutrition sign in the global strategy of the World Health Organization9 and are pursuant to the provisions of the European Charter on Counteracting Obesity10. Therefore, weight management combined with nutritional counseling during the intervention should be an important goal for obese people. Practical knowledge in the field of preparation and composition of the diet, based on the preferred food may be a response to the needs of the patient with the ability to continue healthy cooking at home after finishing weight loss therapy. Overweight and obese patients can achieve a weight loss of as much as 10% of the baseline weight in well-designed programs what significantly decreases the severity of obesity-associated risk factors11.

The aim of this study was to describe the effectiveness of individualized dietary counseling in obese subjects based on narrative interview technique on the maintenance of body weight reduction, changes in dietary behaviors, including type of cooking and physical activity.

Results

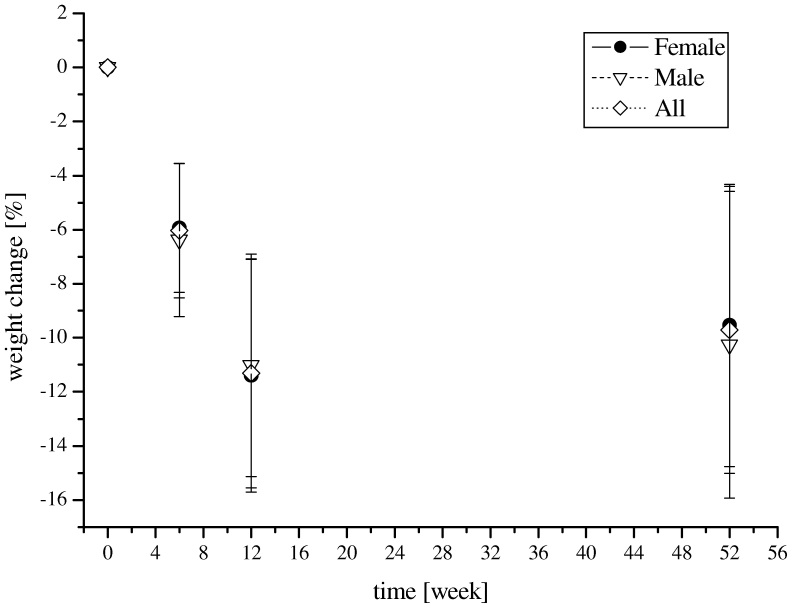

Baseline characteristics of analyzed population were presented in Table 1. Percentages of body weight reductions were independent of age, sex and baseline body weight and were for the whole group, females and males as follows: −5.9%, −5.4%, −7.5% in 6th week, −10.9%, −10.3%, −13.1% in 12th week and −9.7%, 8.7%, 12.8% in 52th week (Fig. 1). Changes in the body weight and BMI revealed to be of high statistical significance (P < 0.0001), however as presented by Dunn's Multiple Comparison test when comparing the body weight and BMI value between 12th and 52th week no statistically significant differences were observed indicating the maintance of obtained weight loss efect (Table 2). In the 6th week 7.1% of all studied subjects (6.3% females and 10% males) reached a 10% body weight reduction. In the further 6-week period of the conducted intervention this threshold was exceeded in 61.1% of the subjects (65.6% females and 55.0% males). After 52 weeks of dietary intervention, 10% reduction of body weight was maintained in 46.4% of the respondents (45.3% females and 50.0% males).

Table 1. The characteristics of analyzed population (n = 100).

| Group | All | Female | Male | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analyzed parameter | Median | Q1–Q3 | Median | Q1–Q3 | Median | Q1–Q3 | ||

| Age [y] | A | 38.0 | 32.2–52.7 | 38.0 | 31.2–52.2 | 41.5 | 34.0–52.7 | ns |

| B | 38.4 | 32.1–54.3 | 37.8 | 30.9–50.7 | 43.4 | 35.2–54.5 | ||

| Weight [kg] | A | 95.0 | 82.1–106.2 | 88.0 | 81.1–100.0 | 116.2 | 99.4–135.9 | ns |

| B | 96.4 | 83.4–106.9 | 88.8 | 80.6–103.4 | 118.1 | 98.3–140.2 | ||

| Height [cm] | A | 166.0 | 161.1–172.0 | 163.5 | 159.0–167.0 | 176.0 | 171.1–181.8 | ns |

| B | 165.5 | 160.8–172.2 | 162.7 | 158.4–166.6 | 176.8 | 172.1–182.1 | ||

| Ethnicity [%] | ||||||||

| Caucasian | A | 100 | 100 | 100 | ns | |||

| B | 100 | 100 | 100 | |||||

| Education [%] | ||||||||

| University degree | A | 7.0 | 6.0 | 10.0 | ||||

| B | 31.0 | 20.0 | 50.0 | |||||

| High school | A | 35.0 | 31.0 | 45.0 | <0.001 | |||

| B | 31.0 | 40.0 | 17.0 | |||||

| Primary school | A | 58.0 | 63.0 | 45.0 | ||||

| B | 38.0 | 40.0 | 33.0 | |||||

| Marital status [%] | ||||||||

| Never married | A | 31.0 | 36.0 | 15.0 | ||||

| B | 19.0 | 20.0 | 16.5 | |||||

| Married | A | 67.0 | 63.0 | 80.0 | ||||

| B | 69.0 | 70.0 | 67.0 | <0.05 | ||||

| Divorced | A | 1.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | ||||

| B | 6.0 | 0.0 | 16.5 | |||||

| Widowed | A | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| B | 6.0 | 10.0 | 0.0 | |||||

Q1, quartile 1; Q3, quartile 3; A, studied group (All: n = 84, female: n = 64; male: n = 20); B, control group (All: n = 16, female: n = 10, male: n = 6); ns, not significant.

Figure 1. The percentage changes in body mass among studied individuals.

*Friedman test showing summarized effect for the all time points; comparisons between each time points showed Dunn's Multiple Comparison test: 0 wk vs 6 wk P < 0.05; 0 wk vs 12 wk P < 0.05; 0 wk vs 52 wk P < 0.05; 6 wk vs 12 wk P < 0.05; 6 wk vs 52 wk P < 0.05; 12 wk vs 52 wk P > 0.05.

Table 2. The changes in body mass and Body Mass Index during dietary modification among analyzed individuals (n = 100).

| Group | Weight [kg] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6-week | 12-week | 52-week | p | |||||

| Median | Q1–Q3 | Median | Q1–Q3 | Median | Q1–Q3 | Median | Q1–Q3 | ||

| Studied group (n = 84) | 95.0 | 82.1–106.2 | 88.9 | 77.1–99.5 | 84.0 | 72.0–94.9 | 88.0 | 73.5–97.0 | <0.0001* |

| Female (n = 64) | 88.0 | 81.1–100.0 | 82.5 | 75.6–94.0 | 77.9 | 71.0–90.0 | 78.0 | 72.0–91.0 | <0.0001* |

| Male (n = 20) | 116.2 | 99.4–135.9 | 109.5 | 92.8–127.0 | 102.6 | 88.2–122.6 | 104.4 | 93.0–115.0 | <0.0001* |

| Control group (n = 16) | 96.4 | 83.4–106.9 | - | - | - | - | 96.7 | 83.7–107 | ns |

| Female (n = 10) | 88.8 | 80.6–103.4 | - | - | - | - | 88.9 | 80.4–103.7 | ns |

| Male (n = 6) | 118.1 | 98.3–140.2 | - | - | - | - | 118.4 | 98.4–140.5 | ns |

Q1, quartile 1; Q3, quartile 3; BMI, Body Mass Index; ns, not significant.

*Friedman test showing summarized effect for the all time points; comparisons between each time points showed Dunn's Multiple Comparison test: 0 wk vs 6 wk P < 0.05; 0 wk vs 12 wk P < 0.05; 0 wk vs 52 wk P < 0.05; 6 wk vs 12 wk P < 0.05; 6 wk vs 52 wk P < 0.05; 12 wk vs 52 wk P > 0.05.

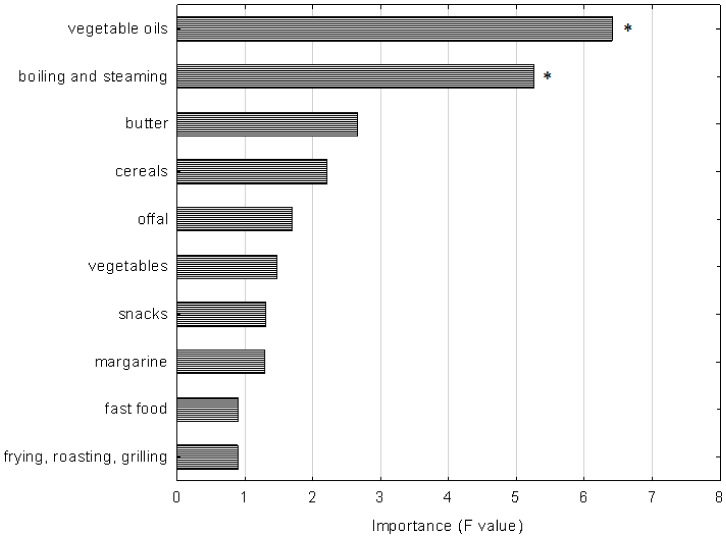

As shown by the Food Frequency Questionnaire (Table 3) over 90% of studied subjects after 52 weeks from the beginning of the study consumed whole-meal bread more frequently than white bread. The frequency of organ meats consumption has decreased in favor of poultry and pork intake. The changes from butter consumption to margarine and vegetable oils were observed. The consumption of snacks and fast food in about 2/3 of subjects fell, contrary however to the amount of sweets which has increased. More frequent intake of water and tea and less frequent intake of juice was observed. The frequency of coffee and alcohol consumption did not change significantly in the studied group. Additionally, over 90% did not change their smoking habits. As far as the type of cooking is concerned, the individuals used more frequently boiling and steaming and more than half individuals fried, roasted and grilled food less frequently. Self-reported increase of physical activity was attributed mostly to walking, gymnastics and swimming. The changes in dietary habits and physical activity were more pronounced among the people maintaining weight loss at level higher than 10% from baseline. Comparing the frequency of selected food intake and cooking techniques from baseline to 52-week of follow-up the statistically significant changes were observed. Decreased frequency of intake of cheese (P < 0.05), eggs (P < 0.01), snacks (P < 0.001), fast food (P < 0.05), juice (P < 0.01) as well as decreased frequency of frying, roasting and grilling (P < 0.05) during meals preparation were observed. The intake of fruits (P < 0.05), margarine (P < 0.05), water (P < 0.01) and sweets (P < 0.01) was increased; similarly boiling and steaming (P < 0.001) were more frequently used techniques. As indicated by the F test, the maintenance of body weight reduction after individualized dietary counseling through 52 weeks, was linked to the pro-healthy changes in type of cooking (more frequent use of boiling and steaming) and increased consumption of vegetable oils (Figure 2).

Table 3. Percentage changes of food frequency intake in relation to weight loss after 52-week follow up.

| % changes in eating behavior | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >10% weight loss (n = 39) | <10% weight loss (n = 45) | ||||||

| Product | less | Unchanged | more | less | unchanged | more | p |

| Wholemeal bread | 7.7 | 0.0 | 92.3 | 4,4 | 0.0 | 95.6 | ns |

| White bread | 94.8 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 84.4 | 11.2 | 4.4 | ns |

| Milk and dairy products | 20.5 | 56.4 | 23.1 | 26.7 | 48.9 | 24.4 | ns |

| Cheeses | 87.2 | 5.1 | 7.7 | 73.3 | 11.1 | 15.6 | <0.05 |

| Vegetable | 7.6 | 82.1 | 10.3 | 4.4 | 84.4 | 11.2 | ns |

| Fruit | 10.3 | 79.4 | 10.3 | 15.6 | 64.4 | 20.0 | <0.05 |

| Pork | 41.0 | 5.2 | 53.8 | 28.9 | 6.7 | 64.4 | ns |

| Poultry | 2.6 | 25.6 | 71.8 | 4.4 | 24.4 | 71.2 | ns |

| Eggs | 5.1 | 94.9 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 80.0 | 8.9 | <0.01 |

| Fish | 15.4 | 56.4 | 28.2 | 8.9 | 60.0 | 31.1 | ns |

| Organ meats | 94.8 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 93.4 | 2.2 | 4.4 | ns |

| Margarine | 15.3 | 46.2 | 38.5 | 17.8 | 26.6 | 55.6 | <0.05 |

| Butter | 82.1 | 17.9 | 0.0 | 77.8 | 17.8 | 4.4 | ns |

| Vegetable oils | 2.6 | 30.7 | 66.7 | 0.0 | 37.8 | 62.2 | ns |

| Sweets | 28.2 | 0.0 | 71.8 | 13.3 | 0.0 | 86.7 | <0.01 |

| Snacks | 79.6 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 57.8 | 17.8 | 24.4 | <0.001 |

| Fast food | 71.8 | 28.2 | 0.0 | 53.3 | 37.8 | 8.9 | <0.05 |

| Tea | 5.1 | 35.9 | 59.0 | 0.0 | 40.0 | 60.0 | ns |

| Coffee | 5.1 | 59.0 | 35.9 | 8.9 | 53.3 | 37.8 | ns |

| Juice | 84.6 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 66.7 | 6.6 | 26.7 | <0.01 |

| Water | 0.0 | 5.1 | 94.9 | 4.4 | 15.6 | 80.0 | <0.01 |

| Boiling and steaming | 2.6 | 5.1 | 92.3 | 17.8 | 11.1 | 71.1 | <0.001 |

| Frying, roasting, grilling | 71.8 | 0.0 | 28.2 | 60.0 | 4.4 | 35.6 | <0.05 |

| Alcohol | 46.2 | 41.0 | 12.8 | 44.4 | 31.2 | 24.4 | ns |

| Physical activity | 61.5 | 20.5 | 18.0 | 64.4 | 15.6 | 20.0 | ns |

ns, not significant.

Figure 2. Predictors influencing body weight maintenance after 52-week follow up.

*P < 0.05.

Discussion

The weight loss of 10% can be maintained for a sustained period after well-designed dietary intervention11. One of the key findings in our research was the demonstration of dietary counseling structured according to relevant topics related to pro-healthy dietary behaviors, based on narrative interview, and the patient's own meal preparation at home as a success platform to maintain weight reduction through changes in cooking methods and sources of fat in daily meals.

It was imperative for the conducted research to incorporate the dietary recommendation in busy lifestyles, because the lack of the time is perceived as a barrier in eating healthy meals13,14,15. The overall time spent on meal preparation decreased significantly in the USA and Europe16,17. Increased availability of tasty, energy-dense foods (e.g. ready prepared meal), eating fewer family meals at home have been blamed to be the major factors in the alarmingly high prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome18,19. Therefore, the involvement of patients, especially the obese ones, in the process of preparing healthy meals is the most recent challenge for nutritionists and clinicians. Our patients were mostly highly educated and worked long hours in the office. As it was indicated by Blackford et al20 the employees working in locations that lack healthy food options can be encouraged to prepare their food at home and to increase self-efficacy through nutrition education. Thus the individual preferences for nutrition strategies included personalized dietary programs, cooking demonstrations, and healthy recipes. Moreover, as shown by Tapsell et al21 the narrative form of a given diet history could be a standardized interview for diet-diseases studies, especially when being combined with other methodologies; for example open-ended in-depth interviews with experienced nutritionists and self-administered questionnaires22. Particularly, narrative structure of consulting based on underreported food still constitutes a challenge for intervention studies. The knowledge about the condition in which selected methods work best and careful consideration of obtained results could identify the aspects that help to deal with diet later on23. Self-management is an important aspect of obesity treatment; however the promotion of self-care activities remains a challenge as shown by Rosenbeck-Minet et al24.

In the present study, 10% reduction of body weight was maintained for a period of 52-week follow up in 46.4% of all studied subjects (45.3% in females and 50% in males) with the mean weight loss of 13.9 kg. Taking into account the maintenance of a 5% reduction in body weight, the figure would reach 84.5% in all studied subjects (85.9% in females and 80% in males) with the mean weight loss of 11.2 kg. Pinto et al25 documented that the individuals who had used a self-guided approach maintained their initial weight losses with a great success, even better than those individuals who had used a very low caloric diet (VLCD). For 18 months 55% of self-guided individuals were maintaining their weight loss within 2.3 kg, as compared to 13% of VLCD. Gripeteg et al26 reported that after successful very low energy diets (VLED) inducing weight loss ≥ 10%, patients with six weeks of re-feeding maintained a significantly greater weight loss (regained: 3.9 ± 9.1%) over one year of treatment than patients with only one week of re-feeding (regained: 8.2 ± 8.3%, P = 0.006). Accordingly, it was suggested that ordinary foods should be re-introduced slowly to enhance weight control after a VLED period. A similar mechanism may have contributed to the maintenance of weight loss in our patients, because at the end of the dietary intervention, subjects received recipes, including the description of slow incorporation of preferred food into menu, connected with changes in energy intake. It should be noted, that in the present research, individualized balanced diet, based on ordinary food, gave us the opportunity to improve the amount of consumed food and its quality associated with type of cooking. According to Yancy et al27 the provision of diet options to patients who desire weight loss could be supported and the choice of the diet enhances adherence and increases weight loss.

In the present research the change of cooking method was one of the most important predictors of weight loss maintenance and it was closely related to the changes in dietary habits. Boiling and steaming were used more frequently in over 90% of studied subjects with >10% weight loss. It is known that some cooking methods (especially frying) are correlated with the increased coronary atherosclerosis risk, overweight or obesity while others (boiling and steaming) decreased such risk28,29. There is no data directly related to changes in cooking type and weight loss maintaince in obese subject. One of the most important aspects is avoiding the high-calorie ingredients during cooking e.g. fat and oils.

Raynor et al30 showed that changing variety in specific food groups may help in adopting and sustaining a diet low in energy and fat, producing better weight loss and weight loss maintenance. They reported that during the first 6 months of the study a weight loss was connected with decreased variety of high fat food, fats, oils and sweets (P < 0.001), what was mediated by change in energy and percentage of dietary fat intake. However, as pointed by the authors30, the variety did not decrease in all food groups, indicating that reductions in intake do not cause decreased variety of a food group. In our study, the consumption of products rich in fat were decreased, especially covering organ meats, butter, margarine and fast food. Moreover, the changes from butter consumption to margarine and vegetable oils were observed, where over 66% of subject with >10% weight loss used vegetable oils more frequently. According to Canfi et al.31 universal predictors for long-term weight loss were: an increased intake of vegetables and meat and a decreased intake of eggs, processed legumes and beverages, what was partially confirmed in the present study. Kruger et al32 pointed to the fact that a combined approach of consuming five or more fruit and vegetable servings per day and attaining 150 minutes or more per week of physical activity can help in successful weight loss maintenance. Unfortunately, in current research the assessment of self-reported changes in physical activity among studied subjects did not give us the possibility to estimate its real association with the energy intake reduction.

In the present study, the lower frequency of snacks intake was observed in studied subjects maintaining a more sustained reduction in body weight (P < 0.001). The use of meal replacements has been demonstrated to be an important predictor of weight loss in the Look AHEAD cohort33, however as underlined by Dasgupta et al34, it does potentially limit the variety and flexibility in dietary intake and therefore may not be uniformly accepted, hence there is a need for the development of alternative strategies. The results of Massey and Hill6 research underline an association between dieting and food craving and the usefulness of distinguishing between dieting and weight loss. It was confirmed that dieters demonstrate stronger cravings especially for foods that are restricted (for example chocolate), than non-dieters. However, the success associated with the maintenance of weight loss by the subjects also had to be linked to the restriction of food craving.

The limitation of the current study is that changes in eating behavior were self-reported, though a validated questionnaire was used. Although the study is limited to Caucasians; results are consistent with other study in different ethnicity35. It should be also noted that although the study was performed with 52-week follow up, the number of participants was not high. The strict inclusion criteria were applied to all included subjects and directly met objectives of the study. This resulted in the small number of participants in the control group, however it does not influence time interaction results in the intervention group. Additionally, there were no differences between control and intervention groups in anthropometrical parameters at the baseline. Moreover, the conclusions have been based upon the changes in dietary habits and weight loss in the intervention group (from baseline through 52-week follow up), therefore the presented results can be valuable. The water consumption was not measured (ad libitum) which could have influence on energy intake. Similarly, we did not monitor physical activity; however the main parameter of our interest were the changes in weight linked to dietary habits. The rationale for this intervention was to promote not only an initial weight loss but also to provide the skills to prepare valuable meals at home as well during counseling period and after finishing a slimming diet. Additionally, the supply of essential nutrients in each individualized balanced diet was similar and nutritional counseling was conducted by the same dietitians, which helped in building long-term relationships with patients. Although the effect of dietary intervention in the maintaining weight loss has been shown previously, new strategies are still searched for. Especially important are these strategies which do not demand the high investment (eg. standardized counselling “face to face” sessions). Therefore, the present study brings important piece of information. More broadened studies are needed to assess predictors of different dietary strategies in obese subjects. Nonetheless, our findings support the merit of this line of enquiry.

In conclusion, individualized dietary counseling, based on narrative interview technique is an effective intervention in obesity treatment that may help maintain a body weight reduction and adapt the pro-healthy changes in type of cooking and sources of dietary fat.

Methods

Patient's recruitment

From four-hundred patients who were admitted to outpatients clinic for obesity treatment between 2011–2013 one-hundred subjects met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The studied group consisted of 84 subjects and was followed for 12 months. Sixteen participants who were enrolled in control group did not receive nutrition and cooking support between pre- and post-consulting period (unwillingness to participate in the educational program) as well through follow-up period (Fig. 3). The inclusion criteria were as follows: 20–65 years old and BMI > 30 kg/m2. The exclusion criteria included: history of bariatric surgery, anorexia nervosa and bulimia, history of depression, vegetarian-dietary habits, diagnosed type 1 or type 2 diabetes, hepatic or renal disorder, myocardial infarction or unstable angina pectoris, coronary artery bypass graft or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, temporal ischemic attack or stroke, cancer, alcohol abuse and participation in another weight-management study or use of medications known to alter food intake or body weight. Twenty participants suffered of hypertension and ten of dyslipidemia. The design of the study was a prospective dietary counseling trial with 52-week follow up and performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. The subjects gave their written consent for the study. Experimental protocol was approved by bioethical committee at Poznan University of Medical Sciences.

Figure 3. The study flow diagram.

Intervention

The subjects were advised by supervisor medical doctor in clinic during the visit to change their habitual diet and increase physical activity. Standardized counseling “face to face” sessions were conducted by qualified nutritionists (MSM and MJ) in the outpatient clinic. In order to allow all participants to express previous experiences related to weight reduction we used a narrative interview technique and the consulting was structured according to relevant topics linked to healthy dietary habits. The section with open questions was used at the beginning to give them the opportunity to explain their stories since they detected that body weight started to increase. Performed interviews were transcribed verbatim. Individual 45-minutes educational program with motivation counseling was performed in 0, 6 and 12 weeks of the study. In every step of the study the nutritionist had explained the basics of healthy nutrition and indicated the main nutritional mistakes in their habitual diet. Additionally, during 12-weeks a telephone and mail-based guidance was conducted. Participants were advised to use individually well-balanced diet for 12 weeks based on patient's food preferences including: 12–14% of energy from protein, 25% from fat and 61–63% from carbohydrates (<10% of energy from saccharose). The daily amount of dietary fiber was 30–35 g/day. The goal of the dietary modification included: reducing the total fat, cholesterol, trans and saturated fatty acids, reducing energy intake, reducing snacks intake, promotion of whole grains products, foods reach in soluble fiber, vegetables, fruits, source of n-3 fatty acids and plant sterols. The energy value of the diet in the first 6 weeks was directly proportional to energy requirement according to Recommended Dietary Allowances for Polish population and in 7–12 weeks and was reduced by 200 kcal12. The water consumption ad libitum was recommended. The participants were advised to prepare meals in their households according to described recommendations. At the baseline they received short handbook which described carefully recommended techniques that should be used during meals preparation eg. steaming and which would maintain the good quality of food. As the standard for estimating the amount of food consumption the subjects were obligated to weight food. The patients were also advised to raise the acceptable, moderate physical activity to 150–200 minutes/week, which was increased slowly during the conducted study.

Data collection

In baseline, 6 and 12-week and 52-week of the study the anthropometrical parameters including body weight and height (RADWAG digital scale with an approximation of 0.5 cm and 0.1 kg respectively) (Radom, Poland) were assessed. Participants were measured without shoes while wearing minimal clothing, after which their BMI was calculated. At baseline and after 52-week of the follow-up the participants were interviewed about their dietary habits and physical activity – self-administrated Food Frequency with Physical Activity Questionnaire was conducted36. This questionnaire included 60 items assessing the frequency of nutritional habits: fruits, vegetables, meat, milk and dairy products, cereal products, fat, alcohol use, sweets and beverages, type of cooking, type and frequency of physical activity.

Statistical approach

Statistica 10.0 (Statsoft Inc. Tulsa, USA) and OriginPro 7.0 (OrifginLab Corp. Northampton, USA) were used for the statistical analysis. The results are given as median values. Friedman test with Dunn's Multiple Comparison test was used to compare the anthropometrical parameters and BMI value by time interaction and Mann Whitney U test to compare the differences between sex groups. Chi-square test was used to describe the changes in the food frequency intake. F test was used to find the most important predictors influencing body weight maintenance after 52-week follow up. The level of significance was set at the standard level of α = 0.05.

Author Contributions

M.S.M., M.M. and J.W. designed the research. M.S.M., M.J. and M.M. conducted the research. W.W. performed the statistical analysis. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

References

- Obesity and overweight - fact sheet No. 311; available at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html World Health Organization (Date of access:14/08/2014).

- Byrne S., Cooper Z. & Fairburn C. Weight maintenance and relapse in obesity: a qualitative study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 27, 955–62 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visram S., Crosland A. & Cording H. Triggers for weight gain and loss among participants in a primary care-based intervention. Br J Community Nurs 14, 495–501 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan S., Hill J. O., Lang W. et al. Recovery from relapse among successful weight maintainers. Am J Clin Nutr 78, 1079–1084 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabinsky M. S., Toft U., Raben A. et al. Overweight men's motivations and perceived barriers towards weight loss. Eur J Clin Nutr 61, 526–531 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey A. & Hill A. J. Dieting and food craving. A descriptive, quasi-prospective study. Appetite 58, 781–785 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neve M. J., Morgan P. J. & Collins C. E. Behavioral factors related with successful weight loss 15 months post-enrolment in a commercial web-based weight-loss programme. Public Health Nutrition 15, 1299–1309 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff S. C., Damms-Machado A., Betz C. et al. Multicenter evaluation of an interdisciplinary 52-week weight loss program for obesity with regard to body weight, comorbidities and quality of life - a prospective study. Int J Obesity 36, 614–624 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. Geneva. World Health Organization (2004). [Google Scholar]

- European Charter on Counteracting Obesity. WHO European Ministerial Conference on Counteracting Obesity. Istanbul (2006). [Google Scholar]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: the evidence report. Obes Res. 6(suppl), 51S–210S (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarosz M. & Bułhak-Jachymczyk B. Human nutrition recommendations. Warszawa, Polska: PZWL. (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Furst T., Connors M., Bisogni C. et al. Food choice: A conceptual model of the process. Appetite 26, 247–266 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors M., Bisogni C. A., Sobal J. et al. Managing values in personal food systems. Appetite 36, 189–200 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogni C. A., Jastran M., Shen L. et al. A biographical study of food choice capacity: Standards, circumstances, and food management skills. J Nutr Educ Behav 37, 284–291 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith L. P., Ng S. W. & Popkin B. M. Trends in US home food preparation and consumption: analysis of national nutrition surveys and time use studies from 1965–1966 to 2007–2008. Nutr J 12, 45 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möser A. Food preparation patterns in German family households. An econometric approach with time budget data. Appetite 55, 99–107 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabs J. & Devine C. M. Time scarcity and food choices: An overview. Appetite 47, 196–204 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud H. R., Zheng H. & Shin A. C. Food reward in the obese and after weight loss induced by calorie restriction and bariatric surgery. Ann NY Acad Sci 1264, 36–48 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackford K., Jancey J., Howat P. et al. Office-based physical activity and nutrition intervention: barriers, enablers, and preferred strategies for workplace obesity prevention, Perth, Western Australia. Prev Chronic Dis. 10, E154 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapsell L. C., Pettengell K. & Denmeade S. L. Assessment of a narrative approach to the diet history. Public Health Nutrition 2, 61–67 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pao E. M. & Cypel Y. S. Estimation of dietary intake. In: Ziegler E., & Filer L. J., eds. Present Knowledge in Nutrition. Washington DC: ILSI Press, 498–508 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Barrett-Connor E. Nutrition epidemiology: how do we know what they ate? Am. J. Clin. Nutr 54 (suppl), 182S–187S (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbek Minet L. K., Lønvig E. M. et al. The experience of living with diabetes following a self-management program based on motivational interviewing. Qual Health Res 21, 1115–1126 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto A. M., Gorin A. A., Raynor H. A. et al. Successful weight loss maintenance in relation to method of weight loss. Obesity 16, 2456–2461 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gripeteg L., Torgerson J., Karlsson J. et al. Prolonged re-feeding improves weight maintenance after weight loss with very-low-energy diets (VLEDs). Br J Nutr 103, 141–148 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancy W. S., Coffman C. J., Geiselman P. J. et al. Considering patient diet preference to optimize weight loss: Design considerations of a randomized trial investigating the impact of choice. Contemp Clin Trials 35, 106–116 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loke A. Y. & Chan Dietary habits of patients with coronary atherosclerosis: case–control study. J Adv Nurs 52, 159–169 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer R. F., Coutinho A. J., Vaeth E. et al. Healthier home food preparation methods and youth and caregiver psychosocial factors are associated with lower BMI in African American Youth. J Nutr 142, 948–954 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raynor H. A., Jeffery R. W., Tate D. F. et al. Relationship between changes in food group variety, dietary intake, and weight during obesity treatment. Int J Obesity 28, 813–820 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfi A., Gepner Y., Schwarzfukchs D. et al. Effect of changes in the intake of weight of specific food groups on successful body weight loss during a multi-dietary strategy intervention trial. J Am Coll Nutr 30, 491–501 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger J., Blanck H. M. & Gillespie C. Dietary practices, dining out behavior, and physical activity correlates of weight loss maintenance. Prev Chronic Dis 5, 1–14 (2008). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Look AHEAD Research Group. The Look AHEAD Study: A description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting It. Obesity (Silver Spring) 14, 737–752 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta K., Hajna S., Joseph L. et al. Effects of meal preparation training on body weight, glycemia, and blood pressure: results of a phase 2 trial in type 2 diabetes. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 9, 1–11 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika S. K., Espeland M. A., Bahnson J. L. et al. Ethnic comparison of weight loss in the trial of nonpharmacologic interventions in the elderly. Obesity Research 10, 96–106 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przysławski J., Stelmach M., Grygiel-Gorniak B., Mardas M. & Walkowiak J. Nutritional status, dietary habits and body image perception in male adolescents. Acta Sci Pol Technol Aliment 9, 383–391 (2010) [Google Scholar]