Abstract

The rarity of bone and soft tissue sarcoma, the difficulty in interpretation of imaging and histology, the plethora of treatment modalities, and the complexity and intensity of the treatment contribute to the need for systematic multidisciplinary team management of patients with these diseases. An integrated multidisciplinary clinic and team with a structured sarcoma tumor board facilitate team coordination and communication. This paper reviews the rationale for multidisciplinary management of sarcoma and details the operational structure of the Multidisciplinary Sarcoma Clinic and Sarcoma Tumor Board. The structured Multidisciplinary Sarcoma Tumor Board provides opportunity for improvement in logistics, teaching, quality, and enrollment in clinical trials.

Keywords: sarcoma, sarcoma care, sarcoma tumor board, collaborative approach

The need for multidisciplinary care in bone and soft tissue sarcoma management

Few, if any, diseases in medicine require multidisciplinary input more than bone and soft tissue sarcomas.1 Sarcomas are rare tumors and require sophisticated pathologic diagnosis and imaging interpretation. Incorrect biopsy technique may compromise surgical options and resectability. Treatment of bone and soft tissue sarcomas routinely includes surgery, but due to the protean anatomic distribution of the disease, surgical input from a variety of surgical disciplines is often required. These disciplines include orthopedic oncology, general surgical oncology, thoracic surgery, and other anatomically directed surgical disciplines. Medical management, routinely used for high grade bone sarcomas and often for large, deep, high grade soft tissue sarcoma, often includes complex multiagent chemotherapy with great toxicity, mandating specific expertise and considerable support. Radiation therapy is given for select tumors either in lieu of surgery or as an adjunct, and is administered with doses that far exceed those given for more routine indications such as bone metastasis.2 Together, these issues mandate close cooperation and multidisciplinary care to optimize outcome.3–5

Diagnosis of bone tumors

Beginning with diagnosis, a sophisticated process is needed for efficient and effective tumor characterization that utilizes a diagnostic triad. In other types of cancers, pathologic interpretation may be performed based solely on the examination of the retrieved specimen. In soft tissue and bone tumors, however, interpretation frequently necessitates understanding of the clinical presentation, along with symptom quality, duration, intensity, and radiographic interpretation of aggressiveness and site. In bone tumors of low grade cartilage origin, the specimen cannot be interpreted in a vacuum, excluding clinical and radiographic factors. A multidisciplinary team is well equipped to discuss image interpretation and clinical presentation with the diagnosing pathologist (Figures 1–4). Similarly, in the interpretation of biopsy specimens, multidisciplinary exchange is essential to determine if a seemingly nondiagnostic biopsy can be interpreted in the clinical and imaging context; if not, future diagnostic maneuvers can be discussed and optimized, leading to fewer unproductive interventions and tests. A core group of dedicated and experienced physicians can accomplish this goal (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Distal femur radiograph.

Notes: Anteroposterior radiograph of the distal femur of a 23-year-old woman presenting with enlargement of distal thigh with occasional pain. Image shows a large mineralized mass.

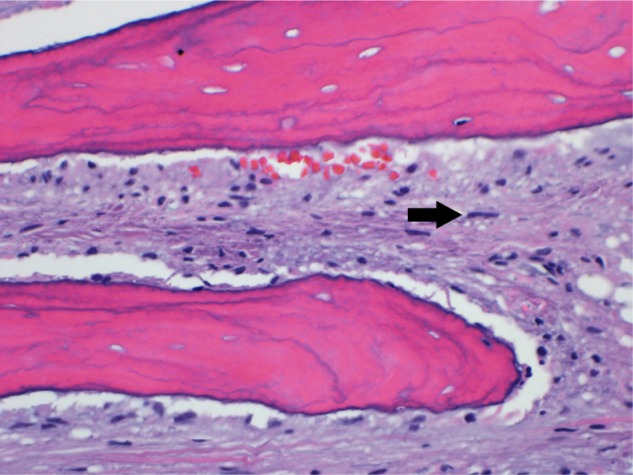

Figure 4.

Distal femur biopsy photomicrograph.

Notes: Photomicrograph of the initial core needle biopsy depicts features of low grade parosteal osteosarcoma. The neoplastic stroma in between bone trabeculae contained spindle cells with small uniform nuclei (arrow). Histology was presented at the Multidisciplinary Sarcoma Tumor Board, and recommendation was made for distal femoral resection (hematoxylin and eosin, 400×).

Table 1.

Multidisciplinary team approach to sarcoma treatment

| Surgical specialists | Medical specialists | Diagnostic specialists |

|---|---|---|

| Primary members | ||

| Orthopedic oncology | Medical oncology | Pathology |

| Surgical oncology | Radiation oncology | Diagnostic radiology |

| Thoracic surgery | Physiatry | |

| Adjunct members | ||

| Plastic surgery | Fertility preservation | Interventional radiology |

| Vascular surgery | Neurosurgery | |

Staging considerations include the diagnostic radiologists, as it is critically important to distinguish incidental findings from true metastases or other processes directly related to the tumor. With increasingly sensitive imaging techniques, it is common to identify lesions that may not be related to the sarcoma at hand. Treatment protocols may vary significantly depending on the correct interpretation of imaging. Additionally, in adolescent and young adult patients, preservation of fertility is an important consideration, and referral and integration with a fertility preserving specialist will allow for efficient discussion of fertility preservation options with the patient, avoiding delay, as much as possible, in initiating chemotherapy.

Treatment of bone cancer

Treatment for the diagnosed primary bone cancer may consist of chemotherapy, resection, and sometimes radiation. Chemotherapy for high grade tumors typically extends 10–12 weeks preoperatively, followed by a “chemotherapy holiday” to allow for recovery prior to the operation. Interdisciplinary collaboration ensures that the patient is medically optimized for surgery and not currently experiencing the grade 3 or 4 marrow toxicities frequently associated with the necessary multiagent chemotherapeutic regimens. The surgeries are often complex (Figure 5) and requiring two or more surgical disciplines: vascular surgery to bypass involved structures, plastic surgery for optimal tissue coverage, and special equipment for skeletal reconstruction. Delaying or rescheduling these cases is difficult and often results in poor resource utilization, as an entire operative suite may be unexpectedly fallow at short notice. Communication between disciplines helps avoid this. Appropriate interpretation of images helps forestall unexpected eventualities in the operating room, optimizing treatment outcome. Processing of the specimen for pathologic interpretation following surgery requires close cooperation with the bone tumor pathologist regarding expected proximity of close margins, as the need for precise interpretation of tumor necrosis in order to establish prognosis and determine subsequent treatment regimens cannot be overemphasized (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Postoperative radiograph.

Note: Anteroposterior radiograph following distal femoral resection and endoprosthetic reconstruction by the orthopedic oncologist.

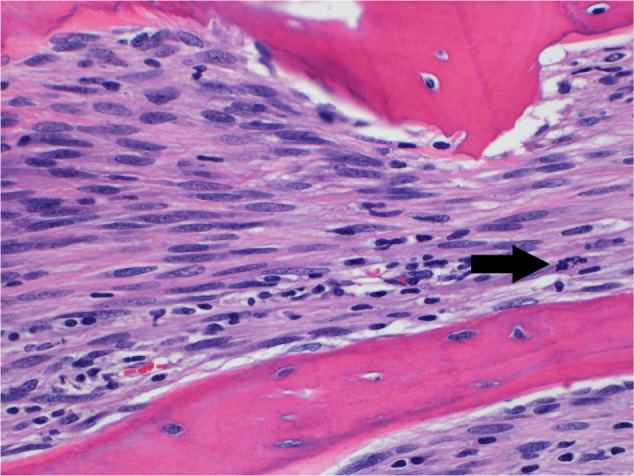

Figure 6.

Distal femur final pathology photomicrograph.

Notes: Evaluation of the complete resection specimen by the musculoskeletal pathologist showed areas of higher grade osteosarcoma. These areas were much more cellular and had larger more atypical nuclei and increased mitotic activity (arrow) compared with the initial biopsy. Following review at the Multidisciplinary Sarcoma Tumor Board, the consensus recommendation for postoperative multiagent chemotherapy was made based on clinical, radiographic, and histologic review (hematoxylin and eosin, 400×).

Soft tissue sarcoma

The management of soft tissue sarcoma also requires integrated care.6 Unfortunately, a large proportion of patients with soft tissue sarcoma may be subject to an initial suboptimal surgery, more often when the multidisciplinary team is not utilized, which may result in the need for more extensive surgery and radiation than the original tumor may dictate.7,8 Diagnosis of the primary lesion, distal metastasis, or subsequent local recurrence requires the use of advanced imaging (magnetic resonance imaging with and without contrast, or computed tomography for biopsy) as well as the expertise of appropriately trained pathologists. Surgeries, especially for wide re-excision after unplanned primary excision of soft tissue sarcoma, often require plastic surgeons for optimal tissue coverage. A questionnaire study of the treatment practices of specialty physicians involved in soft tissue sarcoma care suggests a treatment bias with respect to using, dosing, and timing of radiation and chemotherapy.9 For instance, it was shown that medical oncologists are more apt to recommend chemotherapy as part of the treatment protocol for high grade soft tissue sarcomas. The multidisciplinary treatment team allows specialists versed in the up-to-date literature of all sarcoma specialties to come to a treatment consensus tailored for every individual patient with a soft tissue sarcoma.

Additionally, initial suboptimal management of patients outside centers may be costly. Alamanda et al10 detailed the additional expense with patients undergoing re-excision having an increased $3,699 in professional charges more than those with a primary excision (P<0.001). Inadvertent primary surgery in inexperienced hands may lead to unnecessary amputation.11

Rehabilitation of the sarcoma patient

Following surgery, the patient requires convalescence and rehabilitation, which, in the case of extremity and limb girdle resections and reconstructions, may be markedly dissimilar to other surgical procedures in this age cohort in the extremities. Collaboration with a physiatrist familiar with bone sarcoma and its treatment can help facilitate community reintegration, including optimization of activities of daily living and ultimately re-employment for this group of patients, who are typically relatively young. Additionally, patients for whom significant morbidity may be conferred via treatment may benefit from a pretreatment consultation with a physiatrist, who can discuss with the patient and their family functional outcomes and expectations, as well as develop a pre- and posttreatment rehab plan. This is especially important in patients who may undergo limb amputation, as the rehabilitation process is typically multifaceted and prolonged. Having a physiatrist attend the Sarcoma Tumor Board helps to guide treatment decision making when functional outcome may dictate a specific intervention, and also familiarizes the physiatrist with patients whom they will see in clinic either pre- or posttreatment.

Management of metastatic disease in sarcoma

The prognosis for patients with bone and soft tissue sarcomas metastatic to the lungs has improved significantly over the past three decades, in part due to more aggressive surgical management of pulmonary metastases. The thoracic surgeon has therefore become an integral part of the sarcoma team, and the accurate diagnosis of pulmonary metastases, specifically differentiating them from infection or nonspecific pulmonary nodules, requires close cooperation with medical oncologist and radiologist (Figure 7). Suspected but not definitively diagnosed metastatic nodules may require coordination with an interventional radiologist for biopsy and subsequent assessment by the pathologist. The decision of when and how to evaluate these nodules must be carefully considered in the clinical context provided by the medical oncologist. For example, watchful waiting may be appropriate in some circumstances, and reinstitution of chemotherapy prior to excision may be indicated (Figure 8). Thoracic surgeons can determine the approach and aggressiveness of planned resections in concert with the remainder of the team, taking into account treatment goals, prognosis, and functional status of the patient. In recent years, stereotactic body radiation therapy has emerged as a second option for the treatment of lung metastases. In three to five noninvasive outpatient treatments, local control of 90% can be achieved with minimal toxicity.

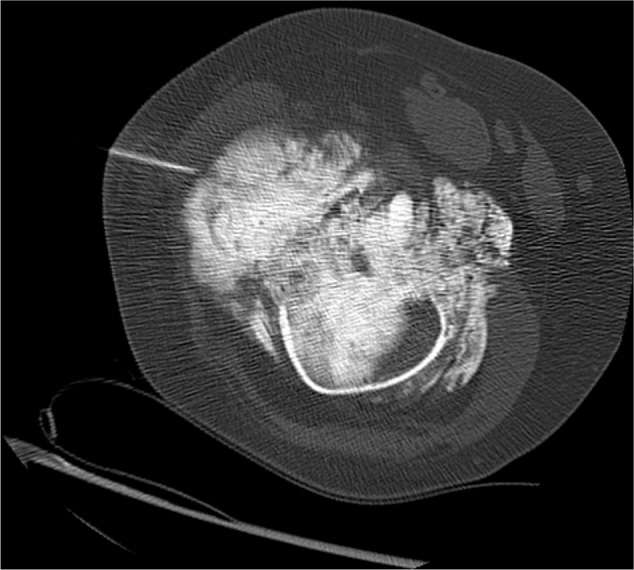

Figure 7.

CT thorax.

Notes: Following a disease-free interval of 18 months following surgery, a lung nodule was identified on routine postoperative surveillance, as seen on this axial computed tomography image. The patient’s care was again reviewed and the consensus recommendation made for second-line chemotherapy followed by resection of the pulmonary nodule with video-assisted thoracic surgery.

Abbreviation: CT, computed tomograhpy.

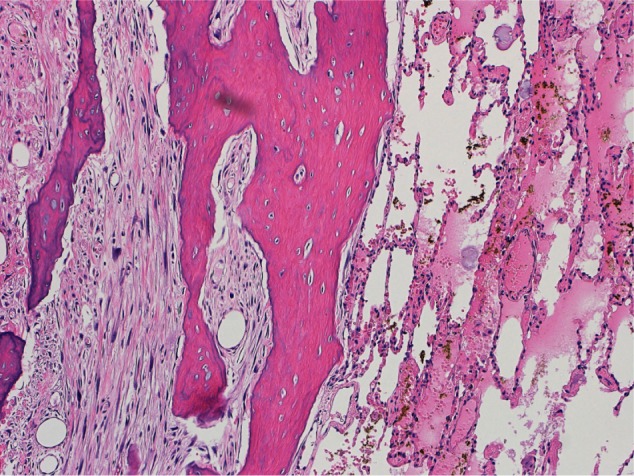

Figure 8.

Metastasectomy photomicrograph.

Notes: Photomicrograph confirms metastatic sarcoma in the lungs resected by the thoracic surgeon. Review of viable disease by the multidisciplinary team led to enrollment of the patient into a clinical trial with an experimental agent. A second metastasectomy procedure 1 year later with wedge resections for pulmonary disease showed focal high grade dedifferentiation but with margins negative. Experimental chemotherapy on clinical trial was resumed. One year following metastasectomy, the patient remains alive without measurable disease, continuing under the care of the multidisciplinary team, 4½ years after initial diagnosis (hematoxylin and eosin, 100×).

Other disease

In addition, the management of soft tissue and bone sarcoma and multidisciplinary treatment of other challenging benign12,13 or malignant14 connective tissue diseases are well orchestrated through the multidisciplinary sarcoma clinic.12,13 As these diseases are so rare, there is generally no other framework for their multidisciplinary review, and the sarcoma group functions as a resource for these patients as well.

The University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center Multidisciplinary Sarcoma Tumor Board and Clinic

Sarcoma Clinic

Patients at the University of Michigan Sarcoma Clinic are seen by multiple providers, depending on the nature of their disease. Each patient receives scheduled appointments for laboratory and plain film imaging, along with appointments with relevant providers in orthopedic oncology or medical oncology within the same physical space. Space within the same building or in an adjacent building facilitates concurrent appointments on the same day with radiation oncology, surgical oncology, and cross-sectional imaging. Close physical proximity and the adjustment of outpatient clinic days allow for coordinated care, which is particularly important for patients coming a long distance. Due to the complexity of care and multidisciplinary needs of these patients, patients who, upon arrival, are determined to need the services of another discipline are often able to be accommodated, and patients who have multiple appointments with different providers may be able to occupy the same examination room without relocating to another area.

Patients are either referred into the clinic and triaged to the most likely provider or referred to a specific provider. In either case, the patient/physician relationship is preserved throughout the process, and providers retain treatment autonomy.

Multidisciplinary Sarcoma Tumor Board

At the University of Michigan, we have a robust bone and soft tissue Sarcoma Tumor Board, which meets weekly, has been in existence for more than two decades, and forms the foundation for multidisciplinary care and collaboration. Attendees include faculty from orthopedic oncology, medical oncology, surgical oncology, radiation oncology, thoracic oncology, diagnostic radiology, pathology, and physiatry. Each faculty member has a specific clinical and academic interest in sarcoma and brings a unique perspective to the group. The Sarcoma Tumor Board is open as a resource for case presentation to all University of Michigan faculty, and, occasionally, attendees come from other disciplines when they have relevant cases, such as otolaryngology or other surgical disciplines.

Good organization is critical to efficient management of the tumor board. This is a working conference, and patients are presented in a streamlined manner with all clinically relevant history and examination findings discussed and a presentation of the imaging germane to the discussion at hand. With an average of ten to 20 sarcoma patients presented weekly, it is important to clarify ahead of time what the critical questions are to be addressed during the session and what imaging or pathology will be needed. Frequently, these patients have extensive histories and multimodality imaging, and the preparation load for the radiologist, although already extensive, would be logistically impossible were the clinicians unable to address ahead of time which imaging would be most helpful. Similarly, the pathology may or may not be critical to the discussion at hand or may be pivotal; clarifying this ahead of time with the pathologist allows for streamlined presentations for education and verification when appropriate, and more detailed discussions of the vagaries of the diagnostic maneuvers when important.

All attendees submit lists of the patients for whom review is requested, along with the images most germane to the topic at hand, and pathology requests. Initial lists are distributed 2–3 business days in advance in order to facilitate clerical processing to optimize workflow for radiology and pathology providers. Patients are presented typically either the same day as their initial clinic visit or within 1 week of the most recent intervention or need for decision points.

The Sarcoma Tumor Board is strategically scheduled midweek to allow for as few absences as possible, and commences late afternoon to allow for a full clinic or operating room day for attendees. Attendees include faculty physicians, residents, fellows, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, medical students, and administrative personnel.

Benefits of the Multidisciplinary Sarcoma Tumor Board

Logistical benefits

Many of the immediate benefits of an organized sarcoma tumor board are self-evident. Providers are able to have planned communication time for discussion and coordination of care with other services, and administrative personnel present may make arrangements to facilitate the treatment plan as needed. One-page notes generated by the presenting service serve as organizational guides for subsequent care, medical documentation of decision making, and a reference back to referring physicians to identify planned and completed therapies. The difficulty in reaching another physician by phone is obviated, and the discussion can be deeper and include more interchange than is often possible by asynchronous electronic communications.

Information transfer

Clinicians who will provide subsequent care to the patients have the advantage of seeing and hearing the entire clinical scenario illustrated and discussed prior to the visits, allowing for a better understanding of the planned intervention. For example, the medical oncologist will be able to review pertinent clinical history, local and remote imaging, and histology. As a result, when the patient arrives to the medical clinic, the physician is completely prepared to present the treatment plan to the patient. Furthermore, nonproductive referrals within the group can be virtually eliminated. For example, a young patient with a readily resectable Ewing’s sarcoma of the fibula may not require referral to the radiation oncologist, or an octogenarian with an extensive chordoma involving the first sacral segment may not be best served by initially seeing a surgeon. Perhaps most importantly, by all providers freely sharing their knowledge, physicians can ensure that they are not overlooking other potential treatment options or subtle radiographic or pathologic findings that will influence the direction of care or prognosis.

Quality

Beyond the benefit of good organization, the Multidisciplinary Sarcoma Tumor Board confers other profound advantages. An internal “second opinion” can be generated with minimal difficulty when cases are viewed by the larger group. Information regarding clinical trials available both within and outside the institution can be rapidly disseminated. A more uniform, comprehensive, institutional approach to management for incoming patients as a result of weekly discussions can prevent the confusion arising when a patient’s diagnostic modalities or care may change depending upon which provider first evaluates the patient.

Case commentaries from all disciplines allow for the eventuality that additional therapeutic options may be necessary that were not identified or anticipated by a single provider operating within their own discipline. For example, the treatment of giant cell tumor of bone has improved markedly with the selective utilization of medical approaches in those patients for whom surgery would be excessively morbid. These subtleties are best explored while reviewing the anatomic detail with the expertise of the radiologists, ensuring no misdiagnoses or malignant transformation present with the pathologist, discussion of surgical options with the orthopedic oncologist, and reviewing the medical indications for therapeutic denosumab treatment with the medical oncologists.

Education

Finally, although the multidisciplinary collaboration is designed as a working conference, there is considerable education at all levels. All providers learn from providers outside of their field what the current advances are, what the germane considerations prior to intervention are, and a considerable amount regarding imaging and/or pathology. Trainees are able to attend and view far more cases than is possible with a mere single faculty mentor or specialty mentor. Midlevel providers learn more about how their field fits into the “big picture” of broader cancer care. Due to the high quality educational experience, a number of trainees not specifically assigned to the conference regularly attend.

Clinical trials

Clinical trial enrollment is critical to furthering the field and can be especially challenging when dealing with uncommon disease. The multidisciplinary tumor board has proved an excellent vehicle for ensuring optimal clinical trial enrollment. All providers with open trials are routinely present and can identify appropriate candidates, which has led to accrual and publication. Additionally, with the collective knowledge of the group of national trials available either in our institution or in other institutions, we are able to maximize options for patients.

Conclusion

The complexity of management of bone and soft tissue malignancies necessitates an organized, structured approach involving many disciplines. The Sarcoma Clinic and Sarcoma Tumor Board are two such vehicles that promote interdisciplinary collaboration and education, leading to better care for patients and a more satisfying experience for providers.

Figure 2.

Distal femur MRI.

Note: Coronal T1-weighted magnetic resonance image shows marrow replacement of distal femur and a soft tissue mass extending beyond the bone cortex.

Abbreviation: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Figure 3.

Distal femur CT biopsy.

Notes: Image-guided biopsy was carried out under computed tomography guidance by the musculoskeletal radiologist following discussion at the Multidisciplinary Sarcoma Tumor Board. The needle trajectory, arrived at upon discussion with the surgical team, is evident.

Abbreviation: CT, computed tomograhpy.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Biermann JS, Adkins DR, Benjamin RS, et al. Bone cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(6):688–723. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagaria SP, Ashman JB, Daugherty LC, Gray RJ, Wasif N. Compliance with National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines in the use of radiation therapy for extremity and superficial trunk soft tissue sarcoma in the United States. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109(7):633–638. doi: 10.1002/jso.23569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nystrom LM, Reimer NB, Reith JD, et al. Multidisciplinary management of soft tissue sarcoma. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:852462. doi: 10.1155/2013/852462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brodak M, Spacek J, Pacovsky J, Krepinska E. Multidisciplinary approach as the optimum for surgical treatment of retroperitoneal sarcomas in women. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2013;34(3):234–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCullough AL, Scotland TR, Dundas SR, Boddie DE. The impact of a managed clinical network on referral patterns of sarcoma patients in Grampian. Scott Med J. 2014;59(2):108–113. doi: 10.1177/0036933014529241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papagelopoulos PJ, Mavrogenis AF, Mastorakos DP, Patapis P, Soucacos PN. Current concepts for management of soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2008;17(3):204–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siebenrock KA, Hertel R, Ganz R. Unexpected resection of soft-tissue sarcoma. More mutilating surgery, higher local recurrence rates, and obscure prognosis as consequences of improper surgery. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2000;120(1–2):65–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Umer HM, Umer M, Qadir I, Abbasi N, Masood N. Impact of unplanned excision on prognosis of patients with extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Sarcoma. 2013;2013:498604. doi: 10.1155/2013/498604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wasif N, Smith CA, Tamurian RM, et al. Influence of physician specialty on treatment recommendations in the multidisciplinary management of soft tissue sarcoma of the extremities. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(7):632–639. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alamanda VK, Delisca GO, Mathis SL, et al. The financial burden of reexcising incompletely excised soft tissue sarcomas: a cost analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(9):2808–2814. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-2995-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venkatesan M, Richards CJ, McCulloch TA, Perks AG, Raurell A, Ashford RU, East Midlands Sarcoma Service Inadvertent surgical resection of soft tissue sarcomas. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38(4):346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams KJ, Hayes AJ. A guide to oncological management of soft tissue tumours of the abdominal wall. Hernia. 2014;18(1):91–97. doi: 10.1007/s10029-013-1156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eastley N, Aujla R, Silk R, et al. Extra-abdominal desmoid fibromatosis: a sarcoma unit review of practice, long term recurrence rates and survival. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40(9):1125–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.02.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahsan F, Inglis T, Allison R, Inglis GS. Cervical chordoma managed with multidisciplinary surgical approach. ANZ J Surg. 2011;81(5):331–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]