Abstract

Background

Chronic migraine is associated with significant headache-related disability and psychiatric comorbidity. OnabotulinumtoxinA (BOTOX®) is effective and well tolerated in the prophylactic treatment of chronic migraine. This study aimed to provide preliminary data on the efficacy and safety of prophylactic onabotulinumtoxinA in patients with chronic migraine and comorbid depressive symptoms.

Methods

This was a prospective, open-label, multicenter pilot study. Eligible patients met International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd edition Revision criteria for chronic migraine and had associated depressive symptoms, including Patient Health Questionnaire depression module scores of 5–19. Eligible participants received 155 units of onabotulinumtoxinA, according to the PREEMPT protocol, at baseline and week 12. Assessments included headache frequency, the Headache Impact Test™, the Migraine Disability Assessment, the Beck Depression Inventory®-II, the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire depression module, and the seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder questionnaire. Adverse events were also monitored.

Results

Overall, 32 participants received treatment. At week 24, there were statistically significant mean (standard deviation [SD]) improvements relative to baseline in the number of headache/migraine-free days (+8.2 [5.8]) (P<0.0001) and in the number of headache/migraine days (−8.2 [5.8]) (P<0.0001) per 30-day period. In addition, there were significant improvements in Headache Impact Test scores (−6.3 [6.9]) (P=0.0001) and Migraine Disability Assessment scores (−44.2 [67.5]) (P=0.0058). From baseline to week 24, statistically significant improvements were also seen in Beck Depression Inventory-II (−7.9 [6.0]) (P<0.0001), Patient Health Questionnaire depression module (−4.3 [4.7]) (P<0.0001), and Generalized Anxiety Disorder questionnaire (−3.5 [5.0]) (P=0.0002) scores. No serious adverse events were reported. Adverse events considered related to treatment occurred in 30% of patients and were mild or moderate.

Conclusion

Prophylactic onabotulinumtoxinA was well tolerated in patients with chronic migraine and comorbid depression, and was effective in reducing headache frequency, impact, and related disability, which led to statistically significant improvements in depression and anxiety symptoms.

Keywords: comorbid anxiety, headache-related disability, migraine prophylaxis

Introduction

Chronic migraine (CM) is a distinct migraine subtype described in the third edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders, requiring a diagnosis of migraine and headache on ≥15 days per month for at least 3 months where on at least 8 days per month, the headaches meet the criteria for migraine or respond to migraine-specific treatment.1 Estimates of CM prevalence range from 0.9%–2.2% in the general population;2,3 in headache centers it is the most common form of chronic daily headache.4 CM significantly interferes with activities of daily living, limiting daily activity and causing substantial loss of productive time, and is associated with both depression and anxiety.3,5–13

Because headaches occur more days than not, CM is usually treated with preventive medications that are intended to reduce headache days per month, improve function, and reduce the need for acute medications, which may be associated with medication overuse.7,14–19 The only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved preventive treatment for CM is onabotulinumtoxinA (BOTOX®; Allergan, Inc. Irvine, CA, USA). Other treatments, including topiramate, divalproex sodium, antihypertensive agents (eg, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers) and antidepressants (eg, amitriptyline, nortriptyline), are used “off-label” in CM prevention. Pooled data from two double-blind, randomized trials (PREEMPT) demonstrate that onabotulinumtoxinA is effective in reducing the number of headache days per month and headache impact, as well as in improving health-related quality of life.20,21

Psychiatric comorbidities, such as depression and anxiety, occur in about one-third of individuals with CM and at significantly elevated rates compared with episodic migraine, in population studies.8,10,22–24 We hypothesized that prophylactic treatment of CM with onabotulinumtoxinA would reduce headache frequency and impact and thereby lead to an improvement in depression and anxiety symptoms in patients with these psychiatric comorbidities. We therefore carried out this open-label, multicenter, pilot study of prophylactic onabotulinumtoxinA in patients with CM and comorbid depression to assess its efficacy and safety in this patient population and to evaluate its potential for reducing depression/anxiety as a consequence of a reduction in headache frequency and headache-related disability.

Methods

Study design and treatment

This was a prospective, open-label, multicenter, pilot study to gather preliminary data on the efficacy and safety of treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA, given at baseline and at week 12, in the prophylactic treatment of CM with comorbid depressive disorders. The study comprised a screening visit (week −4) followed by a 4-week screening phase, a baseline visit (day 0), and two follow-up visits (week 12 and week 24). Follow-up telephone calls were conducted at 4-week intervals. The study was carried out in compliance with the International Conference on Harmonisation guideline for Good Clinical Practice and the current revision of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol and informed consent forms were approved by an Institutional Review Board at each site prior to study initiation. All participants provided written informed consent prior to treatment.

All participants received onabotulinumtoxinA injections at day 0 (baseline) and at week 12 according to the PREEMPT 2 protocol, as previously reported.25 Briefly, study injections were administered, by the principal investigator at each site, as 31 fixed-site, fixed-dose, intramuscular (IM) injections (minimum total dose 155 U) across seven specific head/neck muscle areas. A “follow the pain” strategy with additional dosing was allowed at the investigator’s discretion (maximum total dose 195 U).25

The potency units of onabotulinumtoxinA (BOTOX®) for injection are specific to the preparation utilized. They are not interchangeable with other preparations of botulinum toxin products, and therefore, units of biological activity of onabotulinumtoxinA cannot be compared nor converted into units of any other botulinum toxin product.

Participants

Eligible participants were men and women aged 18 years or older meeting diagnostic criteria for CM according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd edition Revision,26 with history of a mood disorder due to a general medical condition (frequent and severe migraine) and depressive features or depressive episodes/disorders described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) Fourth Edition Text Revision27 for >6 months, as well as one or both of the following at screening (self-assessment): nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) depression module score of 5–19; seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) questionnaire score ≥10. Principal exclusion criteria were: diagnosis of another headache disorder according to the classifications in sections 3 to 14 of the International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd edition;28 history or current diagnosis of psychosis, unstable cyclic mood disorders, bipolar disorder, or suicidal ideation; pregnancy or breast feeding; previous use of any botulinum toxin type A for treatment of any headache (at any time) or nonheadache indication (in the past year); or use of prophylactic medication for headache within 28 days prior to the screening visit. Patients using antidepressants were eligible provided that they had taken a stable dose for >90 days. Use of barbiturates was not permitted at any time during the study. Patients were permitted to use other analgesics on no more than 10 days per month, in order to exclude patients with “medication overuse” headache.

Outcome measures

During the study, participants were evaluated by a physician at week −4, day 0, week 12, and week 24, and by a psychologist at week −4 and week 24 if required. Participants recorded headache characteristics using consecutive monthly headache diaries that were completed throughout the entire study period. The headache efficacy measures were mean change from baseline, at weeks 12 and 24, in number of headache- or migraine-free days, number of headache/migraine days, and intensity of headaches/migraines (reported as the average value for the three consecutive 30-day periods preceding the assessment). A “headache day” was defined as a day (00:00 to 23:59) with ≥4 continuous hours of headache recorded in the patient’s diary. Intensity of headache pain was scored by patients as follows: 1= mild, 3= moderate, or 5= severe. Headache pain was also assessed using a visual analog scale (VAS) at day 0, and weeks 12 and 24, with scores ranging from 0= no pain to 10= most severe pain.14

Headache-related disability and health-related quality of life were assessed at day 0, week 12, and week 24, using the six-item Headache Impact Test (HIT-6),29 the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS),30 and the Short Form (36) Health Survey questionnaire Version 2 (SF-36®) (QualityMetric Inc., Lincoln, RI, USA). Each HIT-6 question was scored as never (6 points), rarely (8 points), sometimes (10 points), very often (11 points), or always (13 points), with questions 4–6 relating to the past 4 weeks, for a total score of 36–78 (≥60= severe impact, 56–59= substantial impact, 50–55= some impact, and ≤49= little to no impact). The MIDAS score was obtained by combining the scores (number of days) for each of five questions relating to the impact of all headaches over the past 3 months, with headache-related disability graded as follows: grade I= little or no disability (score 0–5), grade II= mild disability (6–10), grade III= moderate disability (11–20), grade IV= severe disability (≥21). The SF-36 comprises eight scales relating to two summary measures (physical component and mental component summary scores). Each scale is scored between 0= poor quality of life and 100= good quality of life.

Depression and anxiety symptoms were assessed at day 0, week 12, and week 24, using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II),31 the PHQ-9,32 and the GAD-733 questionnaire. The PHQ-9 and the GAD-7 were also assessed at screening (week −4). The BDI-II is a 21-item, self-report questionnaire used to evaluate severity of depression, based on the past 2 weeks. Cumulative scores (range 0–63) determine the level of depression: 0–13= minimal, 14–19= mild, 20–28= moderate, 29–63= severe. The PHQ-9 consists of nine questions evaluating the frequency of depressive symptoms over the past 2 weeks, which are scored as follows: 0= never, 1= on several days, 2= on more than half of days, 3= nearly every day. Cumulative scores (range 0–27) determine level of depression: 0–4= minimal, 5–9= mild, 10–14= moderate, 15–19= moderately severe, ≥20= severe. The GAD-7 is a seven-item questionnaire used to evaluate the frequency of anxious symptomatology over the past 2 weeks. Each question is scored as: 0= not at all, 1= on several days, 2= on more than half the days, 3= nearly every day. Cumulative scores (range 0–21) determine level of anxiety: 0–4= minimal; 5–9= mild; 10–14= moderate; ≥15= severe. For this study, an additional question was included in both the PHQ-9 and the GAD-7, as question 10 and question 8, respectively, to evaluate the impact of depression and anxiety on occupational disability: “If you checked off any problems, how difficult have these problems made it for you to do your work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people?” Patients could select the following answers: 0= not at all, 1= somewhat difficult, 2= very difficult, or 3= extremely difficult; cumulative scores were also calculated to determine mean change from baseline.

For the safety assessment, subjects were monitored by investigators for adverse events (AEs) and changes in vital signs throughout the study period.

Statistical analysis

This pilot study was intended to facilitate the design of future treatment trials for persons with CM and depressive symptoms. Formal sample size calculations were not possible. We targeted enrollment of approximately 30 patients to facilitate the planning of future studies. All patients who received treatment were included in the efficacy analyses. Statistical analysis was carried out using SAS® 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Analysis of AEs included subjects with at least one postbaseline visit or who reported AEs. Continuous data were summarized using descriptive statistics, and categorical data were summarized using frequencies. Unless otherwise stated, statistical analysis of change from baseline was performed using the paired t-test for headache outcomes, the HIT-6, the MIDAS, the SF-36, and the BDI-II, and using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for pain (VAS), the PHQ-9, and the GAD-7. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a P-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The authors had full access to the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Results

Demographic characteristics and disposition

Of 66 patients screened, 32 were eligible for inclusion in the study, which was conducted at three headache clinics in Canada and the United States between December 2007 and April 2009. The majority of subjects were women and Caucasian (Table 1). At screening, on average, patients were experiencing moderate depression as measured by the PHQ-9 and mild anxiety as measured by the GAD-7. Eight subjects discontinued prior to week 24 (lack of efficacy [n=4]; lost to follow up [n=2]; and withdrew consent [n=2]).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at screening

| Characteristic | Patients (n=32) |

|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 42.4 (12.4) |

| Range | 19–66 |

| Women, n (%) | 28 (87.5) |

| Race and ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 25 (78.1) |

| Black | 1 (3.1) |

| Hispanic | 6 (18.8) |

| PHQ-9, mean (SD) | 10.56 (4.17) |

| GAD-7, mean (SD) | 8.25 (5.66) |

Abbreviations: GAD-7, seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder questionnaire; PHQ-9, nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire depression module; SD, standard deviation.

Headache, headache disability, and health-related quality of life outcomes

At week 24, a statistically significant increase from baseline in the number of headache/migraine-free days was seen, along with a statistically significant reduction from baseline in the number of headache/migraine days (both P<0.0001) (Table 2). There was no significant change from baseline in intensity of headache/migraine pain at week 24 (Table 2). A statistically significant reduction in pain score (VAS) was observed from baseline to week 24 (P<0.0001). At baseline, the mean total HIT-6 score was ~65, indicating severe headache impact. The reduction from baseline in mean total HIT-6 score was statistically significant at week 24 (P=0.0001), resulting in a mean total score below the severe impact threshold at week 24 (Table 2). There was also a statistically significant change from baseline in mean total MIDAS score at week 24, indicating a reduction in migraine-related disability (P=0.0058) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in headache outcomes, pain, and headache-related disability

| Measure | Mean (SD)

|

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n=32) | Week 24 (n=26) | Change from baseline to week 24 (n=25) | ||

| Headache- or migraine-free days per 30-day period | 13.2 (5.5)b | 21.6 (5.4)c | 8.2 (5.8) | <0.0001 |

| Days with headache/migraine per 30-day period | 16.8 (5.5)b | 8.4 (5.4)c | −8.2 (5.8) | <0.0001 |

| Intensity of headache/migraine pain per 30-day perioda | 2.1 (0.4)b | 1.9 (0.4)c,d | −0.2 (0.4)e | 0.0732 |

| Pain score (VAS) | 6.2 (1.5) | 3.8 (2.8)b | −2.5 (2.5) | <0.0001 |

| Total HIT-6 score | 65.3 (4.0) | 59.2 (7.1)b | −6.3 (6.9) | 0.0001 |

| Total MIDAS score | 73.2 (58.2)e | 27.2 (37.6)d | −44.2 (67.5)e | 0.0058 |

Notes:

Patients scored headache pain intensity as: 1= mild, 3= moderate, or 5= severe

data are missing for one patient

average value for the three consecutive 30-day periods preceding the assessment

data are missing for two patients

data are missing for three patients.

Abbreviations: HIT-6, Headache Impact Test; MIDAS, Migraine Disability Assessment; SD, standard deviation; VAS, visual analog scale.

Statistically significant changes from baseline to week 24 were observed for the total SF-36 score, the physical and mental component summary scores, and for all eight SF-36 scales (Table 3).

Table 3.

Changes in health-related quality of life assessed using SF-36® Version 2.0

| Scale | Mean (SD)

|

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n=32) | Week 24 (n=25) | Change from baseline to week 24 (n=25) | ||

| SF-36 Physical Health summary score | 56.4 (18.9) | 69.9 (22.3) | 13.1 (14.8) | 0.0002 |

| Scale 1: physical functioning | 77.7 (21.4) | 82.8 (22.8) | 5.6 (17.6) | 0.0074a |

| Scale 2: role-physical | 53.5 (25.7) | 74.3 (25.8) | 20.6 (19.1) | <0.0001 |

| Scale 3: bodily pain | 38.8 (19.6) | 59.2 (22.3) | 19.1 (19.8) | <0.0001 |

| Scale 4: general health | 55.7 (20.2) | 63.1 (25.5) | 7.2 (15.7) | 0.0305 |

| SF-36 Mental Health summary score | 55.3 (18.0) | 72.8 (20.4) | 17.1 (14.8) | <0.0001 |

| Scale 5: vitality | 37.9 (17.3) | 56.5 (22.8) | 17.5 (21.2) | 0.0004 |

| Scale 6: social functioning | 55.1 (22.6) | 74.5 (25.9) | 18.0 (23.7) | 0.0009 |

| Scale 7: role-emotional | 67.3 (26.6) | 85.3 (21.6) | 17.8 (18.8) | <0.0001 |

| Scale 8: mental health | 60.8 (19.0) | 75.0 (18.9) | 15.0 (10.9) | <0.0001 |

| Total SF-36 score | 55.8 (17.8) | 71.4 (20.8) | 15.1 (13.9) | <0.0001 |

Notes:

Analyzed using Wilcoxon signed-rank method. Higher scores correspond with better functioning on the SF-36.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; SF-36, Short Form (36) Health Survey.

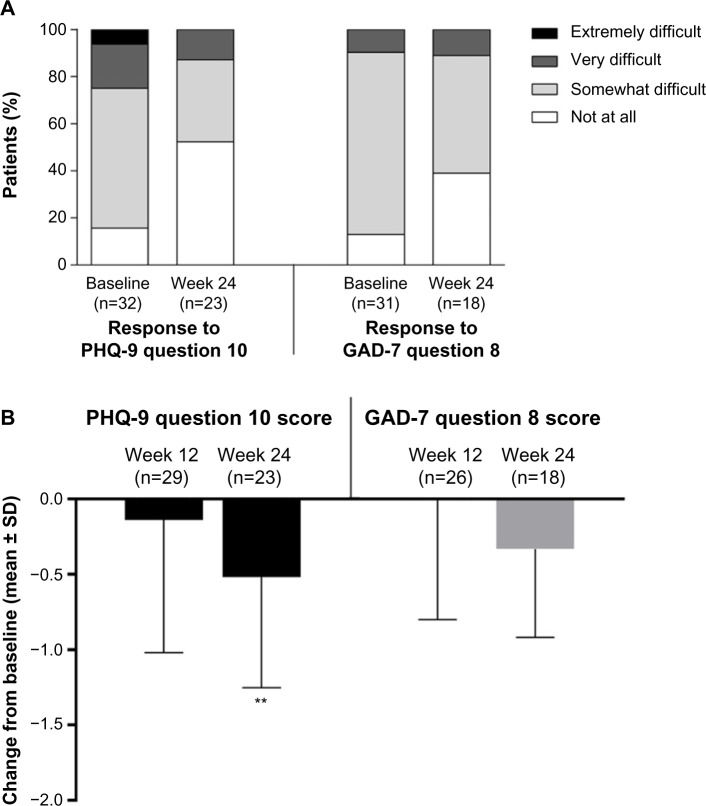

Assessment of psychiatric comorbidities

At baseline, on average, patients were experiencing mild depression as measured by the BDI-II and the PHQ-9, and mild anxiety as measured by GAD-7 (Figure 1). Mean (standard deviation [SD]) changes from baseline in BDI-II and PHQ-9 scores were statistically significant at week 12 (−4.0 [8.7]) [P=0.0166] and −1.9 [5.3] [P=0.0168], respectively) and week 24 (−7.9 [6.0] and −4.3 [4.7], respectively [both P<0.0001]), indicating a reduction in depressive symptoms (Figure 1). For the GAD-7, changes from baseline were statistically significant at week 12 (−1.3 [5.6] [P=0.0313]) and week 24 (−3.5 [5.0] [P=0.0002]), indicating a reduction in anxiety symptoms (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Changes from baseline in depression and anxiety scores.

Note: P-values shown are for mean change versus baseline.

Abbreviations: BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; GAD-7, seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder questionnaire; PHQ-9, nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire depression module; SD, standard deviation.

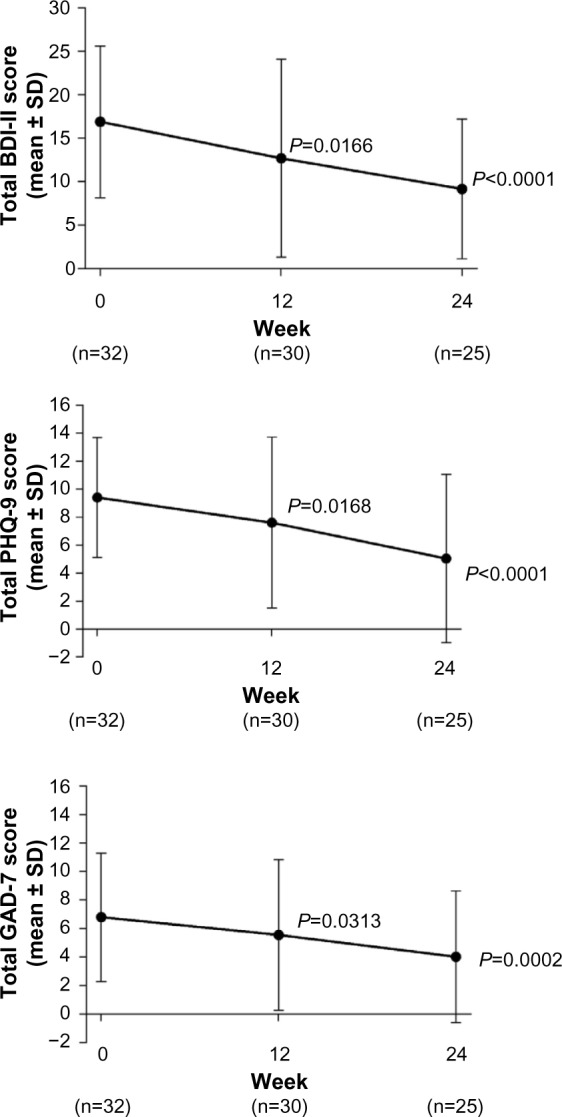

The proportion of subjects who reported that their depression had made their work, domestic chores, and interaction with others “extremely difficult” decreased from 6.3% at baseline to 0% at week 24 and “very difficult” from 18.8% at baseline to 13.0% at week 24. The proportion reporting no interference with their activities (“not at all”) increased from 15.6% at baseline to 52.2% at week 24 (Figure 2A). The proportion of patients who reported that their anxiety had made their work, domestic chores, and interaction with others “somewhat difficult” decreased from 77.4% at baseline to 50.0% at week 24, and the percentage reporting no interference with their activities (“not at all”) increased from 12.9% at baseline to 38.9% at week 24 (Figure 2A). There was no change in the proportion of subjects reporting “very difficult” from baseline to week 24.

Figure 2.

Changes in impact and disability associated with depression and anxiety: patient responses (A) and change from baseline in total score (B).

Notes: The PHQ-9 question 10/GAD-7 question 8 was “If you checked off any problems, how difficult have these problems made it for you to do your work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people?” **P=0.0054 vs baseline.

Abbreviations: GAD-7, seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder questionnaire; PHQ-9, nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire depression module; SD, standard deviation.

As shown in Figure 2B, there was a statistically significant reduction from baseline to week 24 in the overall score for the added PHQ-9 question 10 (interference with daily activities, as stated above) and a numerical reduction (not significant) in overall score for the added GAD-7 question 8 (interference with daily activities).

Safety

Overall, 15 of 30 (50%) subjects assessed for safety experienced AEs. No serious AEs were reported at any time during the study period. AEs considered definitely or probably related to the study treatment occurred in nine of the 30 patients (30%), but these were considered mild or moderate and were fully resolved after a short time. They included cervical muscle pain, eyelid ptosis, injection site bruising, syncope due to injection, unable to move forehead, stiffness in forehead, stiffness in neck, neck tenderness, sensation of weight on neck, constant headache, and tenderness in shoulders. There were no statistically significant changes in vital signs from baseline to week 24.

Conclusion

In this open-label pilot study, treatment of patients with CM and depressive symptoms was associated with statistically significant reductions, from baseline to week 24, in number of headache days, headache pain score (VAS), headache impact (HIT-6), and headache-related disability (MIDAS). In addition, there were statistically significant improvements in depression symptoms (BDI-II and PHQ-9) and anxiety symptoms (GAD-7). Furthermore, improvements from baseline to week 24 were seen in the effects of depression and anxiety on patients’ self-reported ability to work and interact with others, and in mental health and overall general health (SF-36). These results support our hypothesis that, in patients with CM and comorbid depression, treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA would be associated with reductions in headache frequency and impact as well as symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Our study population, recruited from three headache specialty care centers, was broadly representative of the CM patient population seen in clinical practice. Participants had mild to moderate depression and mild anxiety at study entry. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the effect of prophylactic onabotulinumtoxinA on comorbid depression and anxiety in patients with CM as this was not assessed in the PREEMPT trials. These comorbidities are associated with increased rates of progression from episodic to CM.11,34 A proportion of patients with CM and comorbid depression/anxiety symptoms may fulfill the DSM-5® diagnostic criteria for a depressive disorder due to another medical condition rather than a primary depressive disorder. Our findings support the hypothesis that in patients with CM and depression/anxiety, treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA is associated with a reduction in the frequency and impact of migraine attacks and an improvement in the symptoms of depression/anxiety. Larger, blinded, randomized trials are needed to expand upon the findings from this pilot study.

There are several limitations to this pilot study. The sample size was modest, and we did not include a contemporaneous control group. Placebo rates are high in migraine prophylaxis studies,35 including the PREEMPT program, which evaluated onabotulinumtoxinA as a treatment for CM. Placebo rates may be higher and more variable in studies that use parenteral medications and in studies that evaluate preventive medications.36 Additionally, there was no assessment of acute pain medication use during the study.

The mechanism leading to a reduction in both headache outcomes and in measures of depression and anxiety remains to be determined. In this uncontrolled study, a direct therapeutic effect of onabotulinumtoxinA on mood is possible, as are placebo effects on headache and mood. Perhaps onabotulinumtoxinA treatment leads to a reduction in headache, which in turn leads to improvements in depression and anxiety.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Allergan via an independent and unrestricted research grant. Allergan had the opportunity to review the final version of the manuscript, to address any factual inaccuracies or request the redaction of information deemed to be proprietary or confidential, and ensure that study support was disclosed. Writing and editorial assistance was provided to the authors by Helen Varley, PhD, CMPP of Envision Custom Solutions, Horsham, UK and funded by Allergan Inc., Irvine, CA, USA, at the request of the investigator. All authors met the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors authorship criteria. Neither honoraria nor payments were made for authorship. The late Dr Sheftell contributed enormously to headache medicine, and was appreciated by all his colleagues. His suggestions in preparing the protocol of this study were of great value.

Footnotes

Disclosure

GPB receives research support from Amgen. BMG served on a scientific advisory board for Kowa Pharmaceuticals America, Inc. and Tribute Pharmaceuticals; has received speaker honoraria from Zogenix; and receives research support from Allergan, Boston Scientific, and Electrocore. PJM receives research support from Amgen, Allergan, Electrocore, Eli Lilly, Forest Pharmaceuticals, and NuPathe; acts as advisory board member or has received honoraria from Allergan, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ipsen, Merz, Merck, and XenoPort. RBL receives research support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant numbers PO1 AG03949 [as Program Director, Project and Core Leader], RO1AG025119 [Investigator], RO1AG022374-06A2 [Investigator], RO1AG034119 [Investigator], and RO1AG12101 [Investigator]), the National Headache Foundation, and the Migraine Research Fund; serves on the editorial board of Neurology and Cephalalgia and as senior advisor to Headache; has reviewed for the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS); holds stock options in eNeura Therapeutics; serves as consultant, advisory board member, or has received honoraria from Allergan, American Headache Society, Autonomic Technologies, Boston Scientific, Cognimed, Colucid, Eli Lilly, eNeura Therapeutics, Merck, Novartis, NuPathe, Vedanta, and Zogenix. DCB has received grant support and honoraria from Allergan/MAP Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, NuPathe, Zogenix, the National Headache Foundation, and Vedanta Research. FDS is deceased. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders. Cephalalgia. (3rd ed (beta version)) 2013;33(9):629–808. doi: 10.1177/0333102413485658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Natoli JL, Manack A, Dean B, et al. Global prevalence of chronic migraine: a systematic review. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(5):599–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buse DC, Manack AN, Fanning KM, et al. Chronic migraine prevalence, disability, and sociodemographic factors: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study. Headache. 2013;52(10):1456–1470. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bigal ME, Sheftell FD, Rapoport AM, Lipton RB, Tepper SJ. Chronic daily headache in a tertiary care population: correlation between the International Headache Society diagnostic criteria and proposed revisions of criteria for chronic daily headache. Cephalalgia. 2002;22(6):432–438. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dodick DW. Clinical practice. Chronic daily headache. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(2):158–165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp042897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bigal ME, Serrano D, Reed M, Lipton RB. Chronic migraine in the population: burden, diagnosis, and satisfaction with treatment. Neurology. 2008;71(8):559–566. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000323925.29520.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bigal ME, Rapoport AM, Lipton RB, Tepper SJ, Sheftell FD. Assessment of migraine disability using the migraine disability assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire: a comparison of chronic migraine with episodic migraine. Headache. 2003;43(4):336–342. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2003.03068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blumenfeld AM, Varon SF, Wilcox TK, et al. Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs: results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS) Cephalalgia. 2011;31(3):301–315. doi: 10.1177/0333102410381145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stewart WF, Wood GC, Manack A, Varon SF, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Employment and work impact of chronic migraine and episodic migraine. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52(1):8–14. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181c1dc56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buse DC, Silberstein SD, Manack AN, Papapetropoulos S, Lipton RB. Psychiatric comorbidities of episodic and chronic migraine. J Neurol. 2013;260(8):1960–1969. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6725-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashina S, Serrano D, Lipton RB, et al. Depression and risk of transformation of episodic to chronic migraine. J Headache Pain. 2012;13(8):615–624. doi: 10.1007/s10194-012-0479-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buse DC, Manack A, Serrano D, Turkel C, Lipton RB. Sociodemographic and comorbidity profiles of chronic migraine and episodic migraine sufferers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81(4):428–432. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.192492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buse D, Manack A, Serrano D, et al. Headache impact of chronic and episodic migraine: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention study. Headache. 2012;52(1):3–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.02046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bigal ME, Lipton RB, Tepper SJ, Rapoport AM, Sheftell FD. Primary chronic daily headache and its subtypes in adolescents and adults. Neurology. 2004;63(5):843–847. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000137039.08724.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diener HC, Limmroth V. Medication-overuse headache: a worldwide problem. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(8):475–483. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00824-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipton RB, Bigal ME. Chronic daily headache: is analgesic overuse a cause or a consequence? Neurology. 2003;61(2):154–155. doi: 10.1212/wnl.61.2.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Negro A, Martelletti P. Chronic migraine plus medication overuse headache: two entities or not? J Headache Pain. 2011;12(6):593–601. doi: 10.1007/s10194-011-0388-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silberstein SD. Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000;55(6):754–762. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.6.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, Freitag F, Reed ML, Stewart WF, PREEMPT Chronic Migraine Study Group Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68(5):343–349. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252808.97649.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dodick DW, Turkel CC, DeGryse RE, et al. PREEMPT Chronic Migraine Study Group OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: pooled results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phases of the PREEMPT clinical program. Headache. 2010;50(6):921–936. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipton RB, Varon SF, Grosberg B, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA improves quality of life and reduces impact of chronic migraine. Neurology. 2011;77(15):1465–1472. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318232ab65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juang KD, Wang SJ, Fuh JL, Lu SR, Su TP. Comorbidity of depressive and anxiety disorders in chronic daily headache and its subtypes. Headache. 2000;40(10):818–823. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zwart JA, Dyb G, Hagen K, Dahl AA, Bovim G, Stovner LJ. Depression and anxiety disorders associated with headache frequency. The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10(2):147–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2003.00551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radat F, Swendsen J. Psychiatric comorbidity in migraine: a review. Cephalalgia. 2005;25(3):165–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2004.00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diener HC, Dodick DW, Aurora SK, et al. PREEMPT 2 Chronic Migraine Study Group OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 2 trial. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(7):804–814. doi: 10.1177/0333102410364677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olesen J, Bousser MG, Diener HC, et al. Headache Classification Committee New appendix criteria open for a broader concept of chronic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2006;26(6):742–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Press Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society The International Classification of Headache Disorders. Cephalalgia. (2nd ed) 2004;24(Suppl 1):S9–S160. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bayliss MS, Batenhorst AS. The HIT-6: A User’s Guide. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Dowson AJ, Sawyer J. Development and testing of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire to assess headache-related disability. Neurology. 2001;56(6 Suppl 1):S20–S28. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.suppl_1.s20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories-IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess. 1996;67(3):588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashina S, Buse DC, Maizels M, et al. Self-reported anxiety as a risk factor for migraine chronification. Results from The American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. Headache. 2010;50(Suppl 1):S4. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silberstein S, Tfelt-Hansen P, Dodick DW, et al. Task Force of the International Headache Society Clinical Trials Subcommittee Guidelines for controlled trials of prophylactic treatment of chronic migraine in adults. Cephalalgia. 2008;28(5):484–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diener HC, Schorn CF, Bingel U, Dodick DW. The importance of placebo in headache research. Cephalalgia. 2008;28(10):1003–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]