Background: The mechanism of low ADAMTS13 activity observed in many systemic inflammatory syndromes is unknown.

Results: Neutrophil oxidant HOCl inactivates ADAMTS13, and loss of enzyme activity correlates with oxidation of key methionine residues in the enzyme.

Conclusion: Oxidation is one of the potential mechanisms for inactivating ADAMTS13.

Significance: Understanding how oxidants impair ADAMTS13 activity may provide a possible therapeutic insight.

Keywords: ADAMTS13, Inflammation, Myeloperoxidase, Neutrophil, Thrombosis, HOCl, Methionine Oxidation

Abstract

ADAMTS13 is a plasma metalloproteinase that cleaves large multimeric forms of von Willebrand factor (VWF) to smaller, less adhesive forms. ADAMTS13 activity is reduced in systemic inflammatory syndromes, but the cause is unknown. Here, we examined whether neutrophil-derived oxidants can regulate ADAMTS13 activity. We exposed ADAMTS13 to hypochlorous acid (HOCl), produced by a myeloperoxidase-H2O2-Cl− system, and determined its residual proteolytic activity using both a VWF A2 peptide substrate and multimeric plasma VWF. Treatment with 25 nm myeloperoxidase plus 50 μm H2O2 reduced ADAMTS13 activity by >85%. Using mass spectrometry, we demonstrated that Met249, Met331, and Met496 in important functional domains of ADAMTS13 were oxidized to methionine sulfoxide in an HOCl concentration-dependent manner. The loss of enzyme activity correlated with the extent of oxidation of these residues. These Met residues were also oxidized in ADAMTS13 exposed to activated human neutrophils, accompanied by reduced enzyme activity. ADAMTS13 treated with either neutrophil elastase or plasmin was inhibited to a lesser extent, especially in the presence of plasma. These observations suggest that oxidation could be an important mechanism for ADAMTS13 inactivation during inflammation and contribute to the prothrombotic tendency associated with inflammation.

Introduction

ADAMTS13 (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin type 1 motifs 13) (1) is a plasma metalloproteinase that specifically cleaves large multimeric forms of von Willebrand factor (VWF)2 to smaller forms that are less adhesive. Deficiency of this enzyme is associated with the life-threatening microvascular thrombotic disease thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, which is characterized by the accumulation of aggregates of hyper-reactive ultra-large VWF and platelets in the microvasculature (2–5). In addition to thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, reduced ADAMTS13 activity has also been found in systemic inflammatory syndromes such as those caused by endotoxin administration (6), acute pancreatitis (7), severe sepsis (8–12), and severe malaria (13, 14). During inflammation, cytokines, proteases, and reactive oxygen species are released by activated neutrophils and monocytes. Among these, interleukin-6 has been shown to inhibit ADAMTS13 in vitro (15), and in patients with sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation, ADAMTS13 is proteolytically degraded (9, 16). However, it is unclear how reactive oxygen species affect ADAMTS13 activity.

Hypochlorous acid (HOCl) is a potent oxidant produced by activated neutrophils from hydrogen peroxide and chloride ion in a reaction catalyzed by the heme-containing enzyme myeloperoxidase (MPO). HOCl is known to alter protein functions by oxidizing amino acid side chains (17–22). For example, we previously showed that HOCl regulates MMP-7 (matrix metalloproteinase-7) and TIMP-1 (tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1) activity by oxidizing specific cysteine residues (17, 18). We previously reported that HOCl oxidizes and functionally alters VWF, rendering the protein uncleavable by ADAMTS13 by oxidizing Met1606 at the ADAMTS13 cleavage site (21) and increasing its adhesiveness by oxidation of other Met residues (22). Others have reported that reactive oxygen species destroy the function of α1-antitrypsin and thrombomodulin by Met oxidation (19, 20). Here, we examined the effect of Met oxidation on the proteolytic activity of ADAMTS13.

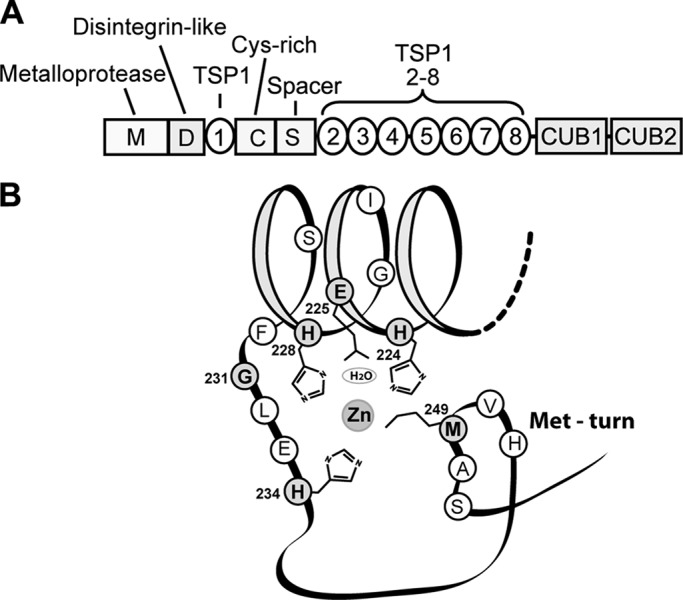

ADAMTS13 contains multiple domains, arranged from the N to C terminus as follows (1): a metalloprotease domain, a disintegrin-like domain, a thrombospondin type 1 (TSP1) repeat, a Cys-rich domain, a spacer domain, seven additional TSP1 repeats, and two CUB (complement C1r/C1s, urinary epidermal growth factor, Bmp1) domains (Fig. 1A). A number of studies have shown that the MDTCS (metalloprotease domain, disintegrin-like domain, TSP1 repeat, Cys-rich domain, spacer domain) domains are essential for proteolytic activity, whereas the C-terminal TSP1 repeat and CUB domains may modulate that activity (23–26). The MDTCS region contains 10 Met residues, Met being the amino acid residue most vulnerable to oxidation by HOCl (27). Importantly, Met249 is predicted to be situated in the “Met-turn” of the metalloprotease domain based on sequence homology with members of the metzincin family of metalloproteases (5, 28), a family to which ADAMTS13 belongs. In members of this family, Met residues at this conserved position are vital to protease activity. A schematic representation of the catalytic site of ADAMTS13 is depicted in Fig. 1B. The zinc ion at the active site of the metalloprotease domain is coordinated with three conserved histidine residues (His224, His228, and His234) and a water molecule polarized by Glu225. Met249 at the Met-turn is important for maintaining the hydrophobic environment of the catalytic site. Mutations in the corresponding Met-turn of TNF-α-converting enzyme render the enzyme inactive (29), suggesting that the Met-turn of ADAMTS13 may also be important for its structure and function. In addition, other Met residues in this region may be involved in the interaction of ADAMTS13 with the VWF A2 domain (30, 31). Because Met oxidation changes the side chain from hydrophobic in character to hydrophilic, it is likely to alter the structure of ADAMTS13 and perturb its interaction with VWF.

FIGURE 1.

Domain structure of ADAMTS13 (A) and schematic representation of the Met-turn in the metalloprotease domain (B) (28, 50). B was adapted from Ref. 28 and revised. Amino acid residues shown in gray fit the consensus sequence for members of the metzincin family.

In this study, we evaluated whether HOCl, a neutrophil-derived oxidant, alters ADAMTS13 activity. We found that HOCl inactivated ADAMTS13 in a process that correlated with oxidation of specific Met residues. Furthermore, we examined whether activated neutrophils inactivate ADAMTS13 in a similar manner and compared inhibitory extent of oxidation to proteolysis by neutrophil elastase or plasmin. Our findings suggest an oxidative mechanism for down-regulating ADAMTS13 activity during inflammation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

The following materials were used: Lipofectamine 2000 and serum-free FreeStyle 293 medium (Invitrogen); MPO (Athens Research & Technology); sodium hypochlorite (Fisher Scientific); dithiothreitol and iodoacetamide (Bio-Rad); sequencing-grade trypsin (Promega); Asp-N (Roche Applied Science); RapiGest SF surfactant (Waters); streptavidin-agarose, streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase, and PMSF (Thermo Scientific); rabbit anti-human VWF polyclonal antibody (Dako); LC-MS-grade acetonitrile (Mallinckrodt Baker); and trifluoroacetic acid and formic acid (EMD). Unless indicated otherwise, all other materials were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

The VWF A2 peptide substrate was based on a 78-amino acid sequence corresponding to the sequence Leu1591–Arg1668 of the VWF A2 domain. The peptide was conjugated to horseradish peroxidase at the N terminus and labeled with biotin at the C terminus (32). Plasma VWF was purified from commercial cryoprecipitate as described previously (21).

Recombinant human ADAMTS13 was produced in HEK293 cells as described previously (21). Serum-free medium containing recombinant human ADAMTS13 was concentrated using an Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter (molecular mass cutoff of 10 kDa; Millipore) and desalted over a PD-10 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4) and 2 mm CaCl2. This solution, containing 1.2 μg/ml ADAMTS13 detected by ELISA (American Diagnostica GmbH) and 0.05 mg/ml total protein concentration, was used as a stock solution for all reactions.

Oxidation of ADAMTS13 by an MPO-H2O2-Cl− System

ADAMTS13 (0.6 μg/ml) was incubated with various concentrations of H2O2 in the absence or presence of 25 or 10 nm MPO in 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 100 mm NaCl, and 2 mm CaCl2 (reaction buffer) at 37 °C for 1 h. The reactions were terminated by adding excess methionine (5 mm final concentration). The concentration of H2O2 was determined by ultraviolet absorption at 240 nm (ϵ240(H2O2) = 39.4 m−1 cm−1) (33).

Isolation of Human Neutrophils

Blood from healthy volunteers was drawn into sodium citrate anticoagulant following a protocol approved by the institutional review board of the University of Washington. Neutrophils were isolated from the blood by buoyant density centrifugation and washed twice with Hanks' balanced salt buffer (magnesium-, calcium-, phenol-, and bicarbonate-free; pH 7.4; Invitrogen). Residual red blood cells were removed by hypotonic lysis at 4 °C. The neutrophils were pelleted, resuspended in Hanks' balanced salt buffer, and used immediately.

Oxidation of ADAMTS13 by Human Neutrophils

Neutrophils were incubated with 0.25 μg/ml ADAMTS13 or ADAMTS13-coated magnetic beads for 1 h in the indicated concentrations of human plasma in Hanks' balanced salt buffer (magnesium-, calcium-, phenol-, and bicarbonate-free; pH 7.4) at 37 °C under constant rotation to maintain the cells in suspension. Neutrophils were activated with 100 nm phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate in the reaction mixture. PMSF (0.5 mm) was used to inhibit serine proteases, and methionine (5 mm) was used as an antioxidant. Reactions were terminated by adding methionine (5 mm final concentration) and removing the neutrophils by centrifugation or recovering the ADAMTS13-coated beads with a magnet.

Measurement of ADAMTS13 Activity by Cleavage of A2 Peptide Substrate

Oxidized ADAMTS13 and unoxidized (control) ADAMTS13 were incubated with the VWF A2 peptide substrate in 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 2 mm CaCl2, and 3.5 mg/ml BSA containing serine protease inhibitors for 10 min at room temperature. The cleavage reaction was terminated by adding 10 mm EDTA and 1 mm NaN3. The reaction mixture was then incubated with streptavidin-agarose beads for 5 min to remove uncleaved substrate. Cleavage product in the supernatant was quantified using tetramethylbenzidine as substrate (34). ADAMTS13 activity was determined by the cleavage rate and normalized to the control, which was assigned an activity of 100%.

Analysis of ADAMTS13 Cleavage of Multimeric Plasma VWF by Gel Electrophoresis

Control ADAMTS13 and oxidized ADAMTS13 (0.3 μg/ml) were incubated with plasma VWF (2 μg/ml) in buffer containing 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 6.5 mm BaCl2, 1.5 m urea, and 1 mg/ml BSA for 4 h at 37 °C. The reactions were stopped by adding 10 mm EDTA. VWF proteolysis was analyzed by electrophoresis of the samples on 1.5% SDS-agarose gels, electrophoretic transfer of the separated proteins to PVDF membranes, and probing the membranes with an HRP-conjugated anti-VWF polyclonal antibody.

Proteolysis of ADAMTS13 by Elastase and Plasmin

ADAMTS13 (0.25 μg/ml) was incubated with 4 μg/ml (0.2 units/ml) elastase or 25 nm plasmin in the absence or presence of 0.5% human plasma in reaction buffer for 0.5 h at 37 °C. The reaction was terminated by adding 0.5 mm PMSF. ADAMTS13 activity was determined by cleavage of multimeric plasma VWF and quantified by LC-MS/MS (see below).

Protein Digestion

Control ADAMTS13 and oxidized ADAMTS13 were reduced with 5 mm dithiothreitol at 70 °C for 20 min, alkylated with 12.5 mm iodoacetamide at room temperature for 15 min, and then digested with trypsin in 50 mm ammonium bicarbonate containing 5% acetonitrile or Asp-N in 50 mm Tris (pH 8.0) with 0.1% RapiGest SF surfactant and 2 mm MgCl2 at a 20:1 (w/w) protein/enzyme ratio overnight at 37 °C. Digestion was terminated by acidification with trifluoroacetic acid. The digested mixtures were concentrated and desalted with C18 extraction disk cartridges, dried under vacuum, and resuspended in 0.1% formic acid and 5% acetonitrile for MS analysis.

LC-MS/MS Analysis

Proteolytic peptides derived from oxidized ADAMTS13 and control ADAMTS13 were analyzed by LC-MS/MS with a Thermo Scientific LTQ Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer coupled to a Waters nanoACQUITY UPLC system. Peptides were separated at a flow rate of 300 nl/min on a nanoACQUITY UPLC BEH130 C18 column (100 × 0.075 mm, 1.7 μm; Waters) using solvent A (0.1% formic acid in water) and solvent B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile). Peptides were eluted using a linear gradient of 5–20% solvent B over 80 min and 20–35% solvent B over 60 min. The spray voltage was 2.0 kV, and the collision energy for MS/MS was 35%. Percent oxidation of individual Met residues was determined by dividing the peak area of the Met-oxidized peptide by the sum of the peak areas for the oxidized and unoxidized peptides.

Quantification of Cleavage of Multimeric VWF by ADAMTS13

Control, oxidized, or protease-treated ADAMTS13 (0.9 μg/ml) was incubated with plasma VWF (3 μg/ml) in buffer containing 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 6.5 mm BaCl2, 1.5 m urea, and 1 mg/ml BSA for 3 h at 37 °C. The reaction mixtures were digested with trypsin as described above. The VWF tryptic peptides containing the ADAMTS13 cleavage site (EQAPNLVY1605M1606VTGNPASDEIK(R)) and the N-terminal ADAMTS13 cleavage product (EQAPNLVY1605) were analyzed by LC-MS/MS.

RESULTS

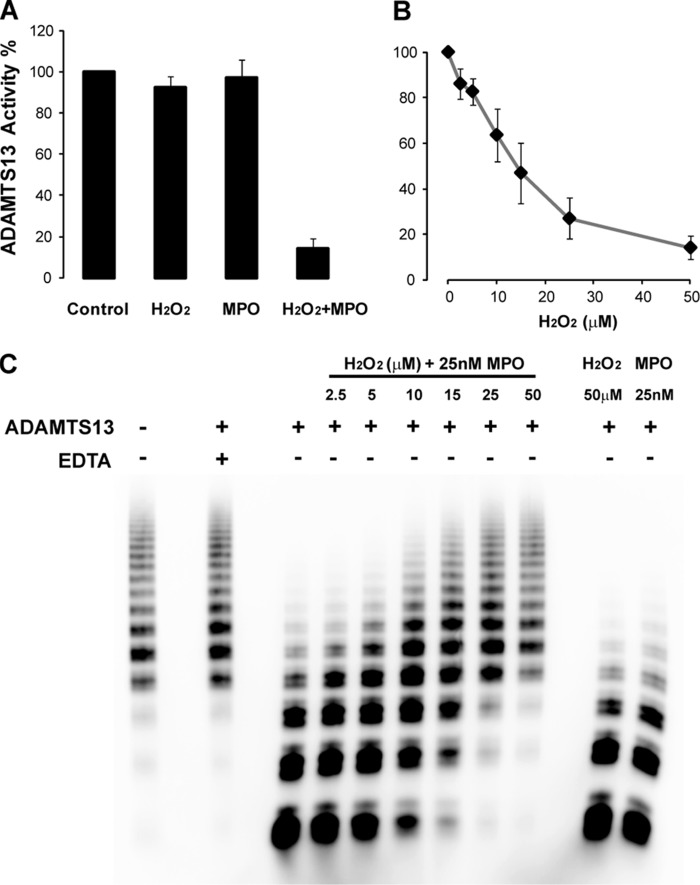

HOCl Generated by an MPO-H2O2-Cl− System Inactivates ADAMTS13

To determine whether HOCl affects ADAMTS13 activity, we first incubated ADAMTS13 with an HOCl-generating system containing H2O2 plus MPO or with H2O2, MPO, or buffer alone. We then determined enzyme activity using an A2 peptide from VWF as a substrate (Fig. 2). Enzyme activity was decreased by >85% after treatment with 50 μm H2O2 and 25 nm MPO (Fig. 2A). The same concentration of either H2O2 or MPO alone had little or no effect on ADAMTS13 activity. We next treated ADAMTS13 with increasing concentrations of H2O2 in the presence of 25 nm MPO. Under these conditions, ADAMTS13 activity was progressively reduced as a function of H2O2 concentration (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

MPO-derived HOCl inactivates ADAMTS13 proteolytic activity. A, ADAMTS13 (0.6 μg/ml) was incubated with reaction buffer alone (Control), 50 μm H2O2, 25 nm MPO, or 50 μm H2O2 in the presence of 25 nm MPO in reaction buffer containing 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 100 mm NaCl, and 2 mm CaCl2 for 1 h at 37 °C. Reactions were terminated by adding excess methionine. The relative activity of ADAMTS13 was determined by cleavage of the A2 peptide substrate in 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 2 mm CaCl2, and 3.5 mg/ml BSA containing serine protease inhibitors for 10 min at room temperature as described under “Experimental Procedures” (34). ADAMTS13 activity was determined by the cleavage rate and normalized to the control, which was assigned an activity of 100%. B, ADAMTS13 activity of cleavage of the A2 peptide substrate after treatment with the indicated concentrations of H2O2 with 25 nm MPO. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of three experiments. C, cleavage of multimeric plasma VWF. Control or oxidized ADAMTS13 was incubated with a purified human plasma VWF fraction in buffer containing 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 6.5 mm BaCl2, 1.5 m urea, and 1 mg/ml BSA for 4 h at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped by adding 10 mm EDTA. Multimeric VWF distribution was analyzed by Western blotting as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

Oxidized ADAMTS13 Fails to Cleave Multimeric Plasma VWF

We then examined the ability of oxidized ADAMTS13 to cleave multimeric plasma VWF under static conditions in the presence of a denaturant (urea). After cleavage, the VWF multimers were separated on a 1.5% SDS-agarose gel by electrophoresis and visualized by Western blotting (Fig. 2C). As we expected, HOCl produced by the MPO-H2O2 system also reduced the ability of ADAMTS13 to cleave multimeric VWF, with the extent of inhibition increasing with increasing H2O2 concentration. After being oxidized with 50 μm H2O2 and 25 nm MPO, ADAMTS13 almost completely lost its ability to cleave multimeric VWF; treatment with MPO or H2O2 alone had little effect.

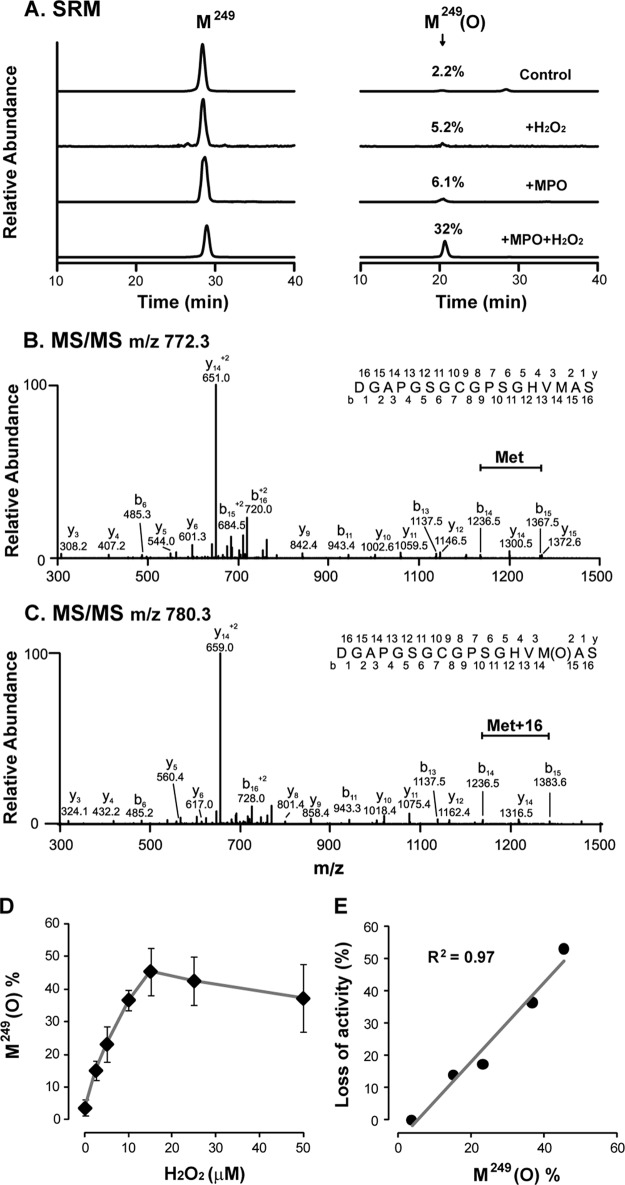

HOCl Oxidizes the Met Residue at the ADAMTS13 Met-turn

Knowing that HOCl damages proteins by oxidation (35, 36), we first focused on the Met residues, which contain side chains most susceptible to oxidation by HOCl (27). One Met residue likely to play an important role in ADAMTS13 function is Met249 in the Met-turn of the metalloprotease domain, which is a conserved feature of all members of the metzincin family. We analyzed proteolytic peptides from oxidant-treated ADAMTS13 by LC-MS/MS (Fig. 3). ADAMTS13 oxidation decreased the abundance of a peptide that contains unoxidized Met249 (Asp235–Ser251), with a concomitant increase in the abundance of an oxidized form of the same peptide (a gain of 16 atomic mass units) (Fig. 3A). The MS/MS spectra confirmed the sequences of the Met249-containing peptide and its oxidized form containing methionine sulfoxide at position 249 (Fig. 3, B and C). In contrast, treatment with H2O2 or MPO alone led to only minimal oxidation of Met249 (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3.

LC-MS/MS analyses of Met-turn peptide (DGAPGSGCGPSGHVM249AS) and its oxidation product. ADAMTS13 was treated as described in the legend to Fig. 2 (A and B). Control or oxidized protein was reduced with dithiothreitol, alkylated with iodoacetamide, and then digested with Asp-N overnight at 37 °C, and the resultant peptides were analyzed by LC-MS and MS/MS. A, selected reaction monitoring (SRM) of the Met-turn peptide (Met249, m/z 772.3 → 650.9 and 842.5) and its oxidized product (Met(O)249, m/z 780.3 → 659.0 and 858.5). The percentage of Met oxidation was determined by dividing the peak area of the oxidized peptide by the sum of the peak area of both the unoxidized and oxidized peptides. B, MS/MS spectrum of the Met-turn peptide (m/z 772.3, doubly charged ion). C, MS/MS spectrum of the oxidized Met-turn peptide (m/z 780.3, doubly charged ion). As indicated, the methionine residue had a gain of 16 atomic mass units. D, oxidation of Met249 after treatment with the indicated concentrations of H2O2 with 25 nm MPO. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of three experiments. E, linear correlation between Met249 oxidation and loss of activity to cleave the A2 peptide when the H2O2 concentration was in the range 0–15 μm.

To investigate whether oxidation of Met249 might account for the loss of ADAMTS13 activity, we exposed ADAMTS13 to increasing concentrations of H2O2 in the presence of 25 nm MPO and analyzed oxidation of Met249 to methionine sulfoxide under each reaction condition. At this MPO concentration, Met249 became increasingly oxidized as the H2O2 concentration increased, reaching a maximum oxidation (45%) at 15 μm H2O2 (Fig. 3D). Oxidation slightly decreased at higher H2O2 concentrations (25 and 50 μm), suggesting that at higher rates of HOCl generation, oxidation of other methionine residues may have changed the protein conformation and protected Met249 from further oxidation. The extent of Met249 oxidation correlated linearly (R2 = 0.97) with loss of proteolytic activity in cleaving the A2 peptide at H2O2 concentrations between 0 and 15 μm (Fig. 3E).

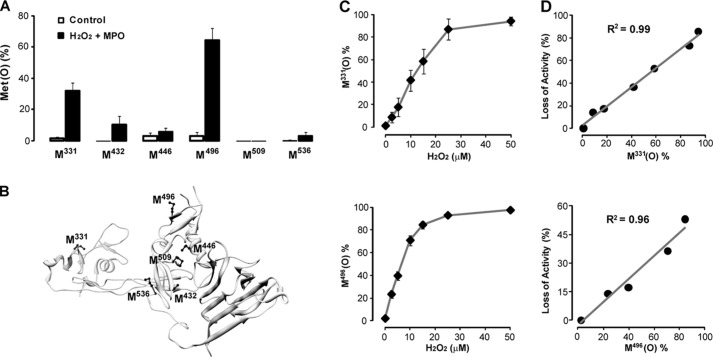

Oxidation of Met Residues in the DTCS Domains of ADAMTS13

The DTCS (disintegrin domain, first TSP1 repeat, Cys-rich domain, spacer domain) domains in ADAMTS13 are essential for ADAMTS13 to bind multimeric VWF before cleaving it (23–26). This region contains eight Met residues: one each in the disintegrin, TSP1 repeat, and spacer domains and five in the Cys-rich domain. The crystal structure of the DTCS domains (Fig. 4B) shows that several Met residues are located on the surface of the molecule (30) and therefore are likely vulnerable to oxidation. We examined Met oxidation in this region in ADAMTS13 treated with 10 μm H2O2 and 25 nm MPO. Of the six Met residues we detected in the DTCS region (Table 1), Met331 and Met496, both located on the surface of the protein, were more susceptible to oxidation than the buried or partly buried Met residues (Fig. 4A). Importantly, studies by Akiyama et al. (30) have shown that Met331 and Met496 are located at exosites that bind the VWF A2 domain; oxidation of these Met residues is therefore likely to contribute to the loss of enzyme activity. Oxidation of both Met residues gradually increased with increasing H2O2 concentration, reaching >85% oxidation at 25 μm H2O2 (Fig. 4C). The extent of oxidation of each Met residue correlated linearly with loss of ADAMTS13 activity (Fig. 4D).

FIGURE 4.

Oxidation of Met residues in the DTCS domains of ADAMTS13. Control ADAMTS13 and oxidized ADAMTS13 were reduced with dithiothreitol, alkylated with iodoacetamide, and then digested with trypsin or Asp-N overnight at 37 °C. A, Met oxidation analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of three experiments. B, Met residues in the DTCS domains of ADAMTS13. Methionine side chains are depicted in ball-and-stick form in the three-dimensional structure of the DTCS domains (30). The surface-exposed Met residues (Met331 and Met496) are more susceptible to oxidation. C, oxidation of Met residues after exposure to the indicated concentrations of H2O2 with 25 nm MPO determined by LC-MS/MS. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of three experiments. D, correlations of Met oxidation with loss of enzyme activity at H2O2 concentrations of 0–50 μm for Met331 and 0–15 μm for Met496.

TABLE 1.

Methionine-containing peptides in the MDTCS domains of ADAMTS13 detected by LC-MS/MS after either trypsin or Asp-N digestion

| Met position | Peptide | Digestion enzyme | Predicted m/z (charge state)a | Observed m/z (charge state) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Met249 | DGAPGSGCGPSGHVMAS | Asp-N | 1543.63 (+1), 772.31 (+2) | 772.31 (+2) |

| Met(O)249 | DGAPGSGCGPSGHVM(O)AS | Asp-N | 1559.63 (+1), 780.31 (+2) | 780.31 (+2) |

| Met331 | DMCQALSCHT | Asp-N | 1222.46 (+1), 611.73 (+2) | 611.73 (+2) |

| Met(O)331 | DM(O)CQALSCHT | Asp-N | 1238.46 (+1), 619.73 (+2) | 619.73 (+2) |

| Met432 | ACVGADLQAEMCNTQACEK | Trypsin | 2155.89 (+1), 1078.44 (+2) | 1078.44 (+2) |

| Met(O)432 | ACVGADLQAEM(O)CNTQACEK | Trypsin | 2171.88 (+1), 1086.44 (+2) | 1086.44 (+2) |

| Met446 | TQLEFMSQQCAR | Trypsin | 1498.68 (+1), 749.84 (+2) | 749.84 (+2) |

| Met(O)446 | TQLEFM(O)SQQCAR | Trypsin | 1514.68 (+1), 757.84 (+2) | 757.84 (+2) |

| Met496 | AIGESFIMK | Trypsin | 995.52 (+1), 498.26 (+2) | 995.52 (+1), 498.26 (+2) |

| Met(O)496 | AIGESFIM(O)K | Trypsin | 1011.52 (+1), 506.26 (+2) | 1011.52 (+1), 506.26 (+2) |

| Met509 | DGTRCMPSGPRE | Asp-N | 1362.59 (+1), 681.80 (+2), 454.87 (+3) | 681.80 (+2), 454.87 (+3) |

| Met(O)509 | DGTRCM(O)PSGPRE | Asp-N | 1378.58 (+1), 689.79 (+2), 460.20 (+3) | 689.79 (+2), 460.20 (+3) |

| Met536 | MDSQQVWDR | Trypsin | 1164.51 (+1), 582.76 (+2) | 582.76 (+2) |

| Met(O)536 | M(O)DSQQVWDR | Trypsin | 1180.51 (+1), 590.76 (+2) | 590.76 (+2) |

a Monoisotope m/z of [M + H]1+, [M + H]2+, or [M + H]3+. All Cys residues in the peptides were alkylated with iodoacetamide.

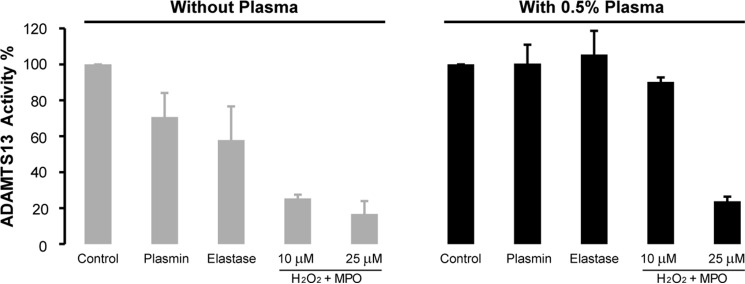

Comparison of ADAMTS13 Activity Loss by Proteolysis and Oxidation

Plasmin and elastase are known to reduce ADAMTS13 activity by proteolytic degradation (9, 16). To compare oxidative inactivation with proteolysis of ADAMTS13 by plasmin and elastase, we exposed ADAMTS13 to plasmin, elastase, or the MPO-H2O2-Cl− system in the absence or presence of plasma proteins and examined ADAMTS13 cleavage of multimeric VWF. Consistent with previous reports (9, 16), in the absence of plasma proteins, both plasmin and elastase inhibited ADAMTS13 to some extent, whereas HOCl produced by the MPO-H2O2-Cl− system more effectively inactivated ADAMTS13 (Fig. 5). In the presence of 0.5% plasma, however, both plasmin and elastase had little effect on ADAMTS13 activity. At the same concentration of plasma, we observed 10 and 76% reduction of ADAMTS13 activity upon treatment with 10 nm MPO and either 10 or 25 μm H2O2, respectively.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of elastase, plasmin, and MPO-generated HOCl on ADAMTS13 activity in the absence or presence of human plasma. ADAMTS13 (0.25 μg/ml) was incubated with PBS (Control), 25 nm plasmin, 4 μg/ml elastase, or 10 or 25 μm H2O2 with 10 nm MPO in reaction buffer in the absence or presence of 0.5% human plasma for 0.5 h at 37 °C. The proteolytic reaction were terminated by adding excess PMSF (0.5 mm final concentration), and the oxidation reactions were terminated by adding excess methionine (5 mm). The activity of ADAMTS13 was determined by cleavage of VWF multimers as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

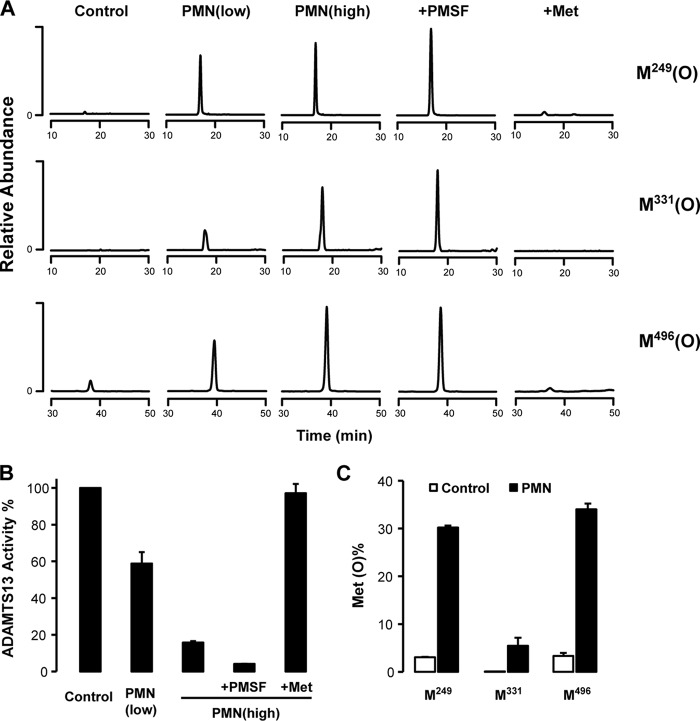

Neutrophils Oxidize ADAMTS13 Methionine Residues

To determine whether activated human neutrophils can oxidize the same three Met residues in ADAMTS13 and thereby impair its proteolytic activity, we first incubated ADAMTS13 with activated neutrophils in the presence of 0.5% plasma and then examined oxidation of Met249, Met331, and Met496 and the cleavage of multimeric plasma VWF. All three methionines were extensively oxidized after treatment with activated neutrophils (2.5 × 106 cells/ml) (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, Met249 and Met496 appeared to be more susceptible to oxidation than Met331 when exposed to a lower concentration of activated neutrophils (1.0 × 106 cells/ml). The enzyme activity determined by the cleavage of multimeric plasma VWF was dramatically decreased upon treatment with activated neutrophils (Fig. 6B). Because activated neutrophils also release proteases (such as elastase) that might cleave and inactivate ADAMTS13 (9), we included PMSF in the reaction system to inhibit serine protease activity (37). Addition of PMSF did not rescue ADAMTS13 activity; rather, the enzyme activity was dramatically inhibited by increased oxidation in the presence of PMSF. Furthermore, addition of 5 mm methionine (antioxidant) effectively protected ADAMTS13 from oxidation and inactivation (Fig. 6, A and B).

FIGURE 6.

Activated neutrophils oxidize Met249, Met331, and Met496 and impair ADAMTS13 proteolytic activity. Neutrophils (PMN) (1 (low) or 2.5 (high) × 106 cells) were incubated with 0.25 μg/ml ADAMTS13 for 1 h with 0.5% (v/v) human plasma in Hanks' balanced salt buffer (magnesium-, calcium-, phenol-, and bicarbonate-free; pH 7.4) at 37 °C under constant rotation. Cells were activated with 100 nm phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate in the absence or presence of PMSF (0.5 mm) or Met (5 mm) in the reaction mixture. The reaction was stop by adding methionine and removing the neutrophils. A, oxidized Met-containing peptides were determined by LC-MS/MS with selected reaction monitoring. The peptides containing oxidized Met249, Met331, and Met496 were monitored: Met(O)249, m/z 780.3 → 659.0 and 858.5; Met(O)331, m/z 619.7 → 504.2 and 735.4; and Met(O)496, m/z 506.3 → 641.3 and 827.4. B, the activity of ADAMTS13 was determined by cleavage of VWF as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Results represent the mean ± S.D. of two experiments. C, biotinylated ADAMTS13 (0.5 μg) was incubated with 20 μl of streptavidin magnetic beads for 30 min at room temperature. ADAMTS13-coated beads were washed with PBS and then incubated with neutrophils as described above. Reactions were terminated by adding excess methionine. The beads were captured with a magnet, washed with PBS buffer, subjected to in-bead digestion, and analyzed by nano-LC-MS/MS. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of two experiments.

To examine whether a higher concentration of plasma would affect ADAMTS13 oxidation by neutrophils, we bound biotinylated ADAMTS13 to streptavidin magnetic beads and then incubated the beads with activated neutrophils in the presence of 90% (v/v) plasma. LC-MS/MS analysis demonstrated that >30% of Met249 and Met496 in ADAMTS13 were oxidized (Fig. 6C).

DISCUSSION

Decreased ADAMTS13 activity during inflammation may be caused by inhibition of ADAMTS13 synthesis (6, 38), proteolysis (9, 16), or consumption due to increased VWF secretion (39). Here, we described a new mechanism for down-regulating ADAMTS13 activity during inflammation. We demonstrated that the neutrophil oxidant HOCl, generated either by an MPO-H2O2-Cl− system or by activated neutrophils, oxidized ADAMTS13 and markedly reduced the enzyme's proteolytic activity.

Among amino acid residues, methionine and cysteine are most sensitive to oxidation. Cysteine thiols are sensitive to oxidation by both H2O2 and HOCl (17, 40). ADAMTS13 contains 77 cysteine residues, some likely present in the reduced form (41). The fact that ADAMTS13 activity was not affected by H2O2 alone (Fig. 2) indicates either that cysteine thiols in ADAMTS13 are inaccessible to oxidation or that the oxidation of cysteine residues does not affect enzyme activity under our experimental conditions. We therefore focused on the oxidation of methionine residues.

We demonstrated that Met249, Met331, and Met496 in the MDTCS region of ADAMTS13 were highly susceptible to oxidation by the MPO-H2O2-Cl− system and that oxidation of these Met residues correlated strongly with the loss of ADAMTS13 activity (Figs. 2 and 3). Met249 is situated in the Met-turn at the catalytic center of the metalloprotease domain. Met331 and Met496 are located in the disintegrin-like and Cys-rich domains, respectively. At low concentrations of oxidants (0–10 μm), the ratios of oxidation to activity loss for Met249, Met331, and Met496 were 1.06, 0.83, and 0.51, respectively. These observations suggest that Met249 oxidation is likely most responsible for the enzyme activity loss, whereas Met331 and Met496 may make lesser contributions to inhibition, despite the fact that they appeared more susceptible to oxidation by HOCl. Interestingly, when ADAMTS13 was exposed to activated neutrophils in diluted plasma, a system that mimics the in vivo situation at sites of inflammation, Met249 became more susceptible to oxidation (Fig. 6A), whereas Met331 oxidation was notably reduced, especially at lower concentrations of neutrophils. These observations imply the possibility that plasma protein(s) may bind to the region closed to Met331 and protect it from being oxidized. Such a binding interaction may also facilitate Met249 exposure to the oxidant, which could explain the ∼75% oxidation in the presence of plasma as shown in Fig. 6A compared with the 45% maximum oxidation by the MPO-H2O2-Cl− system (Fig. 3D). Met496 was also susceptible to oxidation by activated neutrophils, and its oxidation likely contributes to the inactivation of ADAMTS13 because oxidation of this Met may affect its binding to VWF. Consistent with this notion, mutation of Met496 to Gln leads to a 60% loss of enzyme activity (30). Although we reasoned that oxidation of Met249 and Met496 is crucial to inactivation of ADAMTS13, we cannot exclude the possibility that oxidation of other residues contributes to this effect. Nevertheless, we demonstrated that an oxidative mechanism for inactivation of ADAMTS13 likely plays a role in vivo during inflammation.

Proteolytic degradation of ADAMTS13 by elastase (9), plasmin, and other proteases (16) could also potentially reduce ADAMTS13 activity. In our studies, neither elastase nor plasmin significantly inactivated ADAMTS13 in the presence of a low concentration (0.5%) of plasma (Fig. 5). The protective effect of plasma is probably ascribed to serpins (such as α2-antiplasmin, antithrombin, and α1-antitrypsin) present in plasma. These observations suggest that oxidation is likely to be the dominant mechanism for inactivation of ADAMTS13 at sites of inflammation, where neutrophils are recruited in a large numbers. It is worth mentioning that the neutrophil oxidants may also contribute indirectly to ADAMTS13 inactivation by inactivating protease inhibitors, such as α2-antiplasmin, antithrombin, and α1-antitrypsin (19, 20, 42), and increasing ADAMTS13 proteolysis.

In vivo, a number of antioxidant mechanisms are likely to limit ADAMTS13 oxidation under healthy conditions, including the large number of plasma proteins in greater abundance than ADAMTS13. In plasma, ADAMTS13 is present at a concentration of ∼1 μg/ml compared with 60 mg/ml total plasma proteins. During inflammation, however, it is very likely that the effect of neutrophil oxidants on ADAMTS13 is local, allowing these antioxidant systems to be overwhelmed. Millions of neutrophils can be recruited from the circulation to sites of inflammation (43), and when activated, these neutrophils generate high local concentrations of HOCl. Kalyanaraman and Sohnle (44) demonstrated that stimulated neutrophils at 5 × 106 cells/ml can generate 88.3 ± 23.6 μm HOCl. The cationic MPO released by activated neutrophils achieves very high local concentrations by binding anionic proteoglycans on the endothelial surface (45). MPO also is concentrated on the DNA nets that are extruded from the activated neutrophils (46). In both situations, MPO is exposed to additional superoxide substrate, locally produced by activated endothelial cells through the action of the NAD(P)H oxidases NOX1 and NOX4 (47) and through the degradation of the purine bases of DNA by xanthine oxidase. The same conditions that promote superoxide production by endothelial cells also stimulate release of ultra-large VWF from Weibel-Palade bodies, providing a docking site for plasma ADAMTS13 (48). The experimental conditions of ADAMTS13 immobilized on the beads (Fig. 6C) mimic the in vivo conditions of ADAMTS13 bound to ultra-large VWF, as does the high local oxidant concentration. We found >30% oxidation of ADAMTS13 on beads in 90% plasma by activated neutrophils, suggesting that ADAMTS13 is likely oxidized to a higher level at the site of inflammation. In addition, activated neutrophils attached to and likely attempted to ingest the ADAMTS13-coated beads, facilitating oxidation through proximity.

Oxidative inactivation of ADAMTS13 is potentially a common mechanism contributing to the prothrombotic state that accompanies a wide range of diseases with inflammatory components, many of which have been associated with low ADAMTS13 activity (8–14). A number of studies have reported the detection of degraded ADAMTS13 accompanied by decreased ADAMTS13 and protease inhibitor activity (9, 49). The large discrepancies observed between the activity and antigen levels in plasma from patients with acute inflammation could be attributed to both oxidation and proteolysis. Our results suggest that during inflammation, inactivation of ADAMTS13 by oxidation likely occurs before proteolytic degradation. This might explain a previous observation that a C-terminally truncated ADAMTS13 fragment in plasma from a patient with acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura could not cleave the VWF73 peptide substrate (49), even though recombinant C-terminally truncated ADAMTS13 can cleave the same substrate normally (23, 24).

In conclusion, our observations indicate that the neutrophil-derived oxidant HOCl inactivates ADAMTS13. The loss of activity strongly correlates with oxidation of key Met residues in functionally important domains. These findings, together with our earlier observations that oxidation of VWF by HOCl renders it resistant to cleavage by ADAMTS13 (21) and enhances its platelet-binding activity (22), suggest that oxidants contribute to prothrombotic conditions during inflammation. Not only is an increased amount of ultra-large VWF released from endothelial cells, but also its processing is delayed because of oxidation of Met1606 at the ADAMTS13 cleavage site and inactivation of ADAMTS13 by oxidation. All of these mechanisms converge to produce a highly prothrombotic state commonly found in systemic inflammatory syndromes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas Jordan and Jennie Le for assistance with experiments.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R21 HL098672 (to D. W. C.), R01 HL091153 and R01 HL112633 (to J. A. L.), and R01 HL075381 (to X. F.). This work was also supported by institutional funds from the Puget Sound Blood Center (to X. F.).

- VWF

- von Willebrand factor

- MPO

- myeloperoxidase

- TSP1

- thrombospondin type 1.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zheng X., Chung D., Takayama T. K., Majerus E. M., Sadler J. E., Fujikawa K. (2001) Structure of von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease (ADAMTS13), a metalloprotease involved in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 41059–41063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Levy G. G., Motto D. G., Ginsburg D. (2005) ADAMTS13 turns 3. Blood 106, 11–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Manea M., Karpman D. (2009) Molecular basis of ADAMTS13 dysfunction in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Pediatr. Nephrol. 24, 447–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zheng X., Majerus E. M., Sadler J. E. (2002) ADAMTS13 and TTP. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 9, 389–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zheng X. L., Sadler J. E. (2008) Pathogenesis of thrombotic microangiopathies. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 3, 249–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reiter R. A., Varadi K., Turecek P. L., Jilma B., Knöbl P. (2005) Changes in ADAMTS13 (von-Willebrand-factor-cleaving protease) activity after induced release of von Willebrand factor during acute systemic inflammation. Thromb. Haemost. 93, 554–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morioka C., Uemura M., Matsuyama T., Matsumoto M., Kato S., Ishikawa M., Ishizashi H., Fujimoto M., Sawai M., Yoshida M., Mitoro A., Yamao J., Tsujimoto T., Yoshiji H., Urizono Y., Hata M., Nishino K., Okuchi K., Fujimura Y., Fukui H. (2008) Plasma ADAMTS13 activity parallels the APACHE II score, reflecting an early prognostic indicator for patients with severe acute pancreatitis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 43, 1387–1396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kremer Hovinga J. A., Zeerleder S., Kessler P., Romani de Wit T., van Mourik J. A., Hack C. E., ten Cate H., Reitsma P. H., Wuillemin W. A., Lämmle B. (2007) ADAMTS-13, von Willebrand factor and related parameters in severe sepsis and septic shock. J. Thromb. Haemost. 5, 2284–2290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ono T., Mimuro J., Madoiwa S., Soejima K., Kashiwakura Y., Ishiwata A., Takano K., Ohmori T., Sakata Y. (2006) Severe secondary deficiency of von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease (ADAMTS13) in patients with sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation: its correlation with development of renal failure. Blood 107, 528–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bockmeyer C. L., Claus R. A., Budde U., Kentouche K., Schneppenheim R., Lösche W., Reinhart K., Brunkhorst F. M. (2008) Inflammation-associated ADAMTS13 deficiency promotes formation of ultra-large von Willebrand factor. Haematologica 93, 137–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Martin K., Borgel D., Lerolle N., Feys H. B., Trinquart L., Vanhoorelbeke K., Deckmyn H., Legendre P., Diehl J. L., Baruch D. (2007) Decreased ADAMTS-13 (a disintegrin-like and metalloprotease with thrombospondin type 1 repeats) is associated with a poor prognosis in sepsis-induced organ failure. Crit. Care Med. 35, 2375–2382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nguyen T. C., Liu A., Liu L., Ball C., Choi H., May W. S., Aboulfatova K., Bergeron A. L., Dong J. F. (2007) Acquired ADAMTS-13 deficiency in pediatric patients with severe sepsis. Haematologica 92, 121–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Löwenberg E. C., Charunwatthana P., Cohen S., van den Born B. J., Meijers J. C., Yunus E. B., Hassan M. U., Hoque G., Maude R. J., Nuchsongsin F., Levi M., Dondorp A. M. (2010) Severe malaria is associated with a deficiency of von Willebrand factor cleaving protease, ADAMTS13. Thromb. Haemost. 103, 181–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Larkin D., de Laat B., Jenkins P. V., Bunn J., Craig A. G., Terraube V., Preston R. J., Donkor C., Grau G. E., van Mourik J. A., O'Donnell J. S. (2009) Severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria is associated with circulating ultra-large von Willebrand multimers and ADAMTS13 inhibition. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bernardo A., Ball C., Nolasco L., Moake J. F., Dong J. F. (2004) Effects of inflammatory cytokines on the release and cleavage of the endothelial cell-derived ultralarge von Willebrand factor multimers under flow. Blood 104, 100–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Crawley J. T., Lam J. K., Rance J. B., Mollica L. R., O'Donnell J. S., Lane D. A. (2005) Proteolytic inactivation of ADAMTS13 by thrombin and plasmin. Blood 105, 1085–1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fu X., Kassim S. Y., Parks W. C., Heinecke J. W. (2001) Hypochlorous acid oxygenates the cysteine switch domain of pro-matrilysin (MMP-7). A mechanism for matrix metalloproteinase activation and atherosclerotic plaque rupture by myeloperoxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 41279–41287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang Y., Rosen H., Madtes D. K., Shao B., Martin T. R., Heinecke J. W., Fu X. (2007) Myeloperoxidase inactivates TIMP-1 by oxidizing its N-terminal cysteine residue. An oxidative mechanism for regulating proteolysis during inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 31826–31834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Taggart C., Cervantes-Laurean D., Kim G., McElvaney N. G., Wehr N., Moss J., Levine R. L. (2000) Oxidation of either methionine 351 or methionine 358 in α1-antitrypsin causes loss of anti-neutrophil elastase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 27258–27265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Glaser C. B., Morser J., Clarke J. H., Blasko E., McLean K., Kuhn I., Chang R. J., Lin J. H., Vilander L., Andrews W. H., Light D. R. (1992) Oxidation of a specific methionine in thrombomodulin by activated neutrophil products blocks cofactor activity. A potential rapid mechanism for modulation of coagulation. J. Clin. Invest. 90, 2565–2573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen J., Fu X., Wang Y., Ling M., McMullen B., Kulman J., Chung D. W., López J. A. (2010) Oxidative modification of von Willebrand factor by neutrophil oxidants inhibits its cleavage by ADAMTS13. Blood 115, 706–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fu X., Chen J., Gallagher R., Zheng Y., Chung D. W., López J. A. (2011) Shear stress-induced unfolding of VWF accelerates oxidation of key methionine residues in the A1A2A3 region. Blood 118, 5283–5291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ai J., Smith P., Wang S., Zhang P., Zheng X. L. (2005) The proximal carboxyl-terminal domains of ADAMTS13 determine substrate specificity and are all required for cleavage of von Willebrand factor. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 29428–29434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zheng X., Nishio K., Majerus E. M., Sadler J. E. (2003) Cleavage of von Willebrand factor requires the spacer domain of the metalloprotease ADAMTS13. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 30136–30141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Soejima K., Matsumoto M., Kokame K., Yagi H., Ishizashi H., Maeda H., Nozaki C., Miyata T., Fujimura Y., Nakagaki T. (2003) ADAMTS-13 cysteine-rich/spacer domains are functionally essential for von Willebrand factor cleavage. Blood 102, 3232–3237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang P., Pan W., Rux A. H., Sachais B. S., Zheng X. L. (2007) The cooperative activity between the carboxyl-terminal TSP1 repeats and the CUB domains of ADAMTS13 is crucial for recognition of von Willebrand factor under flow. Blood 110, 1887–1894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hawkins C. L., Pattison D. I., Davies M. J. (2003) Hypochlorite-induced oxidation of amino acids, peptides and proteins. Amino Acids 25, 259–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bode W., Gomis-Rüth F. X., Stöckler W. (1993) Astacins, serralysins, snake venom and matrix metalloproteinases exhibit identical zinc-binding environments (HEXXHXXGXXH and Met-turn) and topologies and should be grouped into a common family, the metzincins.' FEBS Lett. 331, 134–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pérez L., Kerrigan J. E., Li X., Fan H. (2007) Substitution of methionine 435 with leucine, isoleucine, and serine in tumor necrosis factor alpha converting enzyme inactivates ectodomain shedding activity. Biochem. Cell Biol. 85, 141–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Akiyama M., Takeda S., Kokame K., Takagi J., Miyata T. (2009) Crystal structures of the noncatalytic domains of ADAMTS13 reveal multiple discontinuous exosites for von Willebrand factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 19274–19279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gao W., Anderson P. J., Sadler J. E. (2008) Extensive contacts between ADAMTS13 exosites and von Willebrand factor domain A2 contribute to substrate specificity. Blood 112, 1713–1719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wu J. J., Fujikawa K., Lian E. C., McMullen B. A., Kulman J. D., Chung D. W. (2006) A rapid enzyme-linked assay for ADAMTS-13. J. Thromb. Haemost. 4, 129–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nelson D. P., Kiesow L. A. (1972) Enthalpy of decomposition of hydrogen peroxide by catalase at 25°C (with molar extinction coefficients of H2O2 solutions in the UV). Anal. Biochem. 49, 474–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wu J. J., Fujikawa K., McMullen B. A., Chung D. W. (2006) Characterization of a core binding site for ADAMTS-13 in the A2 domain of von Willebrand factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 18470–18474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Davies M. J. (2005) The oxidative environment and protein damage. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1703, 93–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Winterbourn C. C. (2002) Biological reactivity and biomarkers of the neutrophil oxidant, hypochlorous acid. Toxicology 181–182, 223–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Furlan M., Robles R., Lämmle B. (1996) Partial purification and characterization of a protease from human plasma cleaving von Willebrand factor to fragments produced by in vivo proteolysis. Blood 87, 4223–4234 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cao W. J., Niiya M., Zheng X. W., Shang D. Z., Zheng X. L. (2008) Inflammatory cytokines inhibit ADAMTS13 synthesis in hepatic stellate cells and endothelial cells. J. Thromb. Haemost. 6, 1233–1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Claus R. A., Bockmeyer C. L., Sossdorf M., Lösche W. (2010) The balance between von-Willebrand factor and its cleaving protease ADAMTS13: biomarker in systemic inflammation and development of organ failure? Curr. Mol. Med. 10, 236–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pattison D. I., Davies M. J. (2001) Absolute rate constants for the reaction of hypochlorous acid with protein side chains and peptide bonds. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 14, 1453–1464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yeh H. C., Zhou Z., Choi H., Tekeoglu S., May W., 3rd, Wang C., Turner N., Scheiflinger F., Moake J. L., Dong J. F. (2010) Disulfide bond reduction of von Willebrand factor by ADAMTS-13. J. Thromb. Haemost. 8, 2778–2788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stief T. W., Aab A., Heimburger N. (1988) Oxidative inactivation of purified human alpha-2-antiplasmin, antithrombin III, and C1-inhibitor. Thromb. Res. 49, 581–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li Y., Karlin A., Loike J. D., Silverstein S. C. (2002) A critical concentration of neutrophils is required for effective bacterial killing in suspension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 8289–8294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kalyanaraman B., Sohnle P. G. (1985) Generation of free radical intermediates from foreign compounds by neutrophil-derived oxidants. J. Clin. Invest. 75, 1618–1622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lau D., Baldus S. (2006) Myeloperoxidase and its contributory role in inflammatory vascular disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 111, 16–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Parker H., Winterbourn C. C. (2012) Reactive oxidants and myeloperoxidase and their involvement in neutrophil extracellular traps. Front. Immunol. 3, 424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Leto T. L., Morand S., Hurt D., Ueyama T. (2009) Targeting and regulation of reactive oxygen species generation by Nox family NADPH oxidases. Antioxid. Redox Signal 11, 2607–2619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Turner N. A., Nolasco L., Ruggeri Z. M., Moake J. L. (2009) Endothelial cell ADAMTS-13 and VWF: production, release, and VWF string cleavage. Blood 114, 5102–5111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Feys H. B., Vandeputte N., Palla R., Peyvandi F., Peerlinck K., Deckmyn H., Lijnen H. R., Vanhoorelbeke K. (2010) Inactivation of ADAMTS13 by plasmin as a potential cause of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J. Thromb. Haemost. 8, 2053–2062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Levy G. G., Nichols W. C., Lian E. C., Foroud T., McClintick J. N., McGee B. M., Yang A. Y., Siemieniak D. R., Stark K. R., Gruppo R., Sarode R., Shurin S. B., Chandrasekaran V., Stabler S. P., Sabio H., Bouhassira E. E., Upshaw J. D., Jr., Ginsburg D., Tsai H. M. (2001) Mutations in a member of the ADAMTS gene family cause thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Nature 413, 488–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]