Abstract

This paper describes marriage and partnership patterns and trends in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa from 2000-2006. The study is based on longitudinal, population-based data collected by the Africa Centre demographic surveillance system. We consider whether the high rates of non-marriage among Africans in South Africa reported in the 1980s were reversed following the political transformation underway by the 1990s. Our findings show that marriage has continued to decline with a small increase in cohabitation among unmarried couples, particularly in more urbanised areas. Comparing surveillance and census data, we highlight problems with the use of the ‘living together’ marital status category in a highly mobile population.

1. Introduction

By the 1980s, when retrospective analyses of African censuses and fertility surveys showed that changes in nuptiality were occurring in many sub-Saharan countries, marriage patterns in South Africa were already exceptional (Harwood-Lejeune 2000; Lesthaeghe & Jolly 1995; Van de Walle 1993). The mean age of marriage for men (28.0 years) was higher than all other regions in Africa, and that of women (23.2 years) was one of the highest (Locoh 1988). In seeking to document and explain the early and advanced decline in African marriage in South Africa, authors have paid particular attention to the profound and lasting influences of apartheid policies. In the 1990s, it was unclear if, and how, the anticipated increase in political, social, and economic opportunities for Africans resulting from political change would affect family life. Taken in their entirety, contemporary tribal, religious, and legislative structure and processes are favourable towards marriage and seek to promote it as the preferred family institution. The action by the country’s first post-apartheid government to formulate a new marriage act that sought to recognise and legitimise the plural religious and ethnic marriage traditions in the country exemplifies strong social norms about the positive value of marriage. Would political change lead to a reversal in the movement away from universal marriage? However, at the same time as political transformation, South Africa started to experience a rapid and severe HIV epidemic further complicating predictions of future trends in marriage. Any impact of HIV and AIDS on marriage, re-marriage, and widowhood would occur in tandem with other social and economic changes affecting people’s decisions about family formation (Heuveline 2004).

For demographers seeking to document trends in marriage and partnering in South Africa, there are surprisingly few sources of data. In a country where marriage is far from universal, the lack of discrimination between marital states and cohabitation arrangements in the most recent South African censuses limits the interest of this data (Budlender, Chobokoane, and Simelane 2005; Ziehl 1999). Furthermore, relating marriage and partnership trends to the complex social and residential arrangements in which many people live in South Africa, needs detailed, population-based data. In this paper, we use demographic surveillance system data on a population of approximately 86,000 people in rural KwaZulu-Natal between 2000-2006. The Africa Centre Demographic Information System (ACDIS) was established with the purpose of collecting empirical data about socio-demographic change and has been well documented (Hosegood, Benzler, and Solarsh 2005; Hosegood and Timæus 2005; Tanser et al. 2007). Data on marriage, non-marital partnerships and patterns of cohabitation are collected routinely in ACDIS.

This paper describes contemporary patterns and trends in marriage and partnering in rural KwaZulu-Natal. The descriptive findings are a starting point for further research on this subject. They fill a gap in the South Africa marriage and household literature, and provide a platform for exploring causative factors. The paper is structured as follows. We first review the literature relating to marriage in South Africa, with a specific focus on Zulu marriage traditions. We then describe the ACDIS data used in the study and provide background information about the study population and area. We present population trends in patterns of marriage and partnerships, and describe the household and residential arrangements of partners. In the appendix, we present a detailed comparison of marital data from ACDIS with the 2001 South African census data from the same province.

2. Marriage and partnering in South Africa: A review of the literature

2.1 Influence of apartheid-era policies and labour migration

Of the many reasons that have been suggested for the decline in marriage and increases in marital instability among African South Africans, most relate directly or indirectly to the oppressive social and political structures and processes created during the apartheid-era. The labour migration system created during the apartheid-era has been a profound force of instability and change in African family life. An extensive literature documents the effects of government policies on labour migration, restrictions of free movement, and the creation of tribal homelands placed on family building, living and care arrangements, and livelihoods (see for example, Jones 1992; Mayer 1980; Murray 1980, 1981, 1985; Spiegel 1980; Spiegel, Watson, and Wilkinson 1996).

The apartheid-era policies not only required most couples from rural areas to live apart, but when one or both partners took up paid employment actively sought to prevent them staying together or visiting each other elsewhere. The 1952 Pass Laws Act which was in effect until 1986, made it illegal for African adults to stay in an urban area without employment and accommodation (Maharaj 1992). The barriers placed in the way of migrants being joined by their partners and children are illustrated by the regulations of hostels built to accommodate African migrants residing in the urban areas (Wilson 1972). The majority of hostels were designated as single-sex hostels. In male hostels, the presence of women and children was illegal but inconsistently enforced. Ethnographic studies of family life in these hostels by Jones (1993) and Ramphele (1993) describe the harsh, chaotic, and insecure conditions in which families in hostels lived.

The effect of men’s absence from the rural family home, the formidable challenges faced by families in urban areas, and the high levels of female participation in the labour market has been shown to exacerbate the poor quality of gender relationships in South Africa (Moore 1994). Migration of both men and women created separate spheres of living, where the different social, physical, and cultural worlds inhabited by the couple were incompatible or even threatening to each other (Preston-Whyte 1993). In this context, migrant men and women took other partners and formed second families at the places where they worked. Women entered the labour force in large numbers and were able to provide for themselves and their children with or without the support of male partners (Bozzoli 1991). One outcome of this separation was the increase in the instability of marriages, not merely because of physical separation, but by altering the roles of husbands and wives.

Over and above the impact of labour migration on marriage and family stability, research has identified its influence on marriage attitudes and behaviour. As the strength and formality of the affinal bond weakened following decades of labour migration and policies whose unintended, and in some cases intended, consequence was to keep young married couples and their families apart; social structures and support realigned around the stronger and more enduring parental and filial bonds. Parents and siblings often proved a more reliable and enduring source of emotional, financial, and material support than marital partners (Niehaus 1994; Preston-Whyte 1978, 1988). Ethnographic studies in South Africa repeatedly highlighted the gendered perspectives that exist in negotiating and entering marriage, one in which both men and women seem to often lose more than they gain. For women, expectations of a ‘traditional’ wife are at odds with modern female identity as empowered, income earner, educated, and able to control their own fertility (van der Vliet 1991). For contemporary Zulu women ‘doing without marriage’ is viewed by some commentators as a positive choice and indeed one of the survival strategies used by disadvantaged poorer women (Muthwa 1995; van der Vliet 1984). Others argue that marriage remains an ideal for most women and that rather than a reduction in the value of marriage, circumstances have altered making it more difficult to realise (Preston-Whyte 1993). Masculinity scholars have also described the dilemma between marriage ideals and experience. Men are dissuaded from entering marriage by fears that they will be prevented from playing authority, provider, and family-builder roles. In addition to the threat of opposition from female partners, financial constraints in paying bridewealth, as well as the costs of supporting a partner, children and other relatives, are barriers to men marrying (Mkhize 2006; Morrell 2006; Townsend, Madhavan, and Garey 2006). In contrast to our knowledge of women’s decision making in marriage, childbearing, and family formation in South Africa, there has been much less attention to men’s attitudes and lifetime conjugal partnering and parenting patterns (Montgomery et al. 2005; Morrell and Richter 2006).

2.2 Overview of the legal and traditional context of marriage in South Africa

The post-apartheid Recognition of Customary Marriages Act, Act 12 of 1998 was a radical attempt to recognise the diversity of cultural and religious traditions in South Africa, at the same time as increasing the role of the state in protecting the rights of women within marriage, particularly with regards to children and property (Chambers 2000; Posel 1995). The 1998 Recognition of Customary Marriages Act permitted marriages solemnised only through customary or traditional laws to be recognised as legal marriages. Whereas previously, only Natal (now KwaZulu-Natal) had permitted, or rather compelled, Africans to register customary unions (Posel 1995). The 1998 Act, which came in to effect in 2000, declared that all customary unions could be considered as legal marriages provided that criteria relating to consent and community of property are met, and that the marriage is registered (Budlender, Chobokoane, and Simelane 2005). The 1998 Marriages Act also recognised polygamous unions. Polygamy is synonymous with polygyny in South Africa given the exceedingly rare occurrences of polyandry. Budlender, Chobokoane, and Simelane (2005) suggest that the rate of polygamy reported in surveys and the South African Census may be over-estimated due to a social desirability bias, leading respondents to report additional non-marital partners as ‘wives’.

2.3 Marriage and childbearing in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

From the 1950s, anthropologists have drawn attention to the decline in marriage among the Zulu-speaking population of South Africa’s largest province by population, KwaZulu-Natal (de Haas 1984; Gluckman 1950; Preston-Whyte 1974). Using data from ethnographic studies, researchers linked marital instability and non-marriage to changes in family life including rising numbers of extra-marital births, increases in the proportion of female-headed households, as well as matrifocal or female-linked households (de Haas 1984; Pauw 1963; Preston-Whyte 1978; Wilson 1969). Data from the 1970 South African Census showed that in rural KwaZulu-Natal, 14% of men and 5% of women aged 50 years and older, were reported to have never been married or were living in a non-marital cohabiting relationship. By the 2001 South African Census, these proportions had risen to 27% and 18% respectively. These rates of non-marriage and non-martial cohabitation are among the highest of South Africa’s nine provinces (Udjo 2001). Researchers have sought to explore the extent to which the apartheid policies that indirectly deterred as well as delayed marriage were exacerbated by specific features of the Zulu marriage and childbearing tradition, in particular the high cost of bridewealth and a tacit acceptance of extra-marital fertility (Burman and Preston-Whyte 1992; Burman and van der Werff 1993; Goody 1973).

The economic, religious, political, and legal circumstances which have given rise to contemporary patterns of marriage in KwaZulu-Natal are complex. The abutting of Western and African ideologies, traditions, and political power has been a story of incorporation and opposition. So-called ‘Bantu marriages’ were thought by many administrators and civic leaders to be a ‘great evil’ and a cause of family and social degeneration (Posel 1995). The legacy of the early Natal administrators is that they co-opted and codified bridewealth. While historically the amount of bridewealth was negotiated by the families involved and was rarely paid in full before marriage took place, the Natal code subjected Zulu women to a fixed, and very high bridewealth of eleven head of cattle or their equivalent value (Burman and van der Werff 1993; de Haas 1987; Preston-Whyte 1993). From Union in 1910 to the first democratic elections in 1994, successive national administrations sought to gain control over the diverse ‘traditional’ or ‘customary’ marriage practices (McClendon 2008). African marriage was subject to the parallel legal systems created for Africans based on codifying an assortment of contemporary and historical indigenous customary laws. In contrast, several indigenous marriage customs were eschewed by Christian missionaries and later the established Christian congregations in South Africa, which strongly proscribed against polygyny and the levirate (widow inheritance). In Natal, the Natal Code of Black Law (1967) altered the requirements for consent, bridewealth and divorce (see description in Cassim 1981). It was not until the new South African Marriages Act (1998) that all marriage systems were recognized as equal. Customary marriages that comply with the provisions of the act are now considered as valid marriages.

Specific features of the Zulu marriage and childbearing tradition may make marriage more vulnerable than in other population and language groups. Many authors have noted the exceptionally high price of Zulu bridewealth. Called ilobolo in Zulu, it involves a payment or transfer of property from the groom’s family to the bride’s family. The cost and complexity of the marriage process increases when families follow, as most do, both the traditional Zulu and Christian marriage ceremonies and rites. Traditional paternity claims require a man to either marry the child’s mother or pay ‘damages’ to her family. It has been argued that the existence of the second option encouraged men to avoid the higher costs and obligations of marriage whilst claiming their children (Hunter 2006). In the 1980s and 1990s, despite the context of economic disadvantage and high unemployment, 70% of Zulu-speaking respondents thought that the custom of ilobolo would survive, twice the proportion of Xhosa-speakers, another large ethnic group in South Africa (Burman and van der Werff 1993).

However, it is the value placed on childbearing and its precedence over marriage that has had the most influence in shaping contemporary Zulu family life. Preston-Whyte and Zondi (1992) noted: ‘There is a sense in which the value placed upon children is so high for many people that marriage is, in some contexts, quite irrelevant to the bearing of a child. This is not to suggest that in general marriage is not regarded as the appropriate arena for birth. It is. But failing marriage, children have a value in themselves which cannot be gainsaid.’ However, this intrinsic value has not stopped fertility among African South Africans from falling steadily over the last forty years (Moultrie and Timæus 2003). While fertility data for Africans in KwaZulu-Natal are not available for the 1970s or 1980s, by the time of the 1996 census, fertility among Africans in KwaZulu-Natal was 3.7 children per woman. Five years later, in 2001, fertility in the same group was 3.2 children per woman (Moultrie and Dorrington 2004). The decline is primarily driven by long birth intervals and high rates (at least by regional standards) of contraceptive use. Although life-time fertility is lower in unmarried women, extra-marital fertility is nonetheless very high, and fertility differentials by marital status are small (Moultrie and Timæus 2001). The severe HIV epidemic in KwaZulu-Natal has not been shown to be a main determinant of aggregate fertility decline. A recent study using longitudinal population-based data in rural KwaZulu-Natal (ACDIS data) suggests that fertility in or up to 2005 may have in fact stalled (Moultrie et al. 2008).

3. Data and methods

3.1 Study area

The Africa Centre Demographic Information System (ACDIS) is located in the Umkhanyakude district in northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Around two hundred kilometres north of Durban, this is one of the poorest districts in KwaZulu-Natal (Case and Ardington 2004). The area includes land under the Zulu tribal authority that was formerly classified as a homeland under the apartheid-era Bantu Authorities Act of 1951 (Crankshaw 1993), as well as an urban township under municipal authority. The township was formerly designated for African residents. Infrastructure development and population density across the area are heterogeneous, ranging from fully serviced town houses to isolated rural homesteads without water, electricity, or sanitation. The population is highly mobile; approximately 40% of male and 35% of female adult household members (18 years or older) reside outside the area but return periodically and maintain social relationships with households (Hosegood, Benzler, and Solarsh 2005; Hosegood et al. 2004; Hosegood and Timæus 2005). Although most of the study area is rural, few households are engaged in subsistence agriculture, and most are dependent on waged income and state grants. The unemployment rate, the percentage of the economically active, is high (39% of people aged 15–65 years in 2001) (Case and Ardington 2004). Rural areas of KwaZulu-Natal have very high levels of HIV prevalence and as yet there is no evidence of a decline in incidence (Bärnighausen et al. 2007; Dorrington et al. 2006; Welz et al. 2007). HIV prevalence in the surveillance area has reached high levels in the antenatal population (38% in 2005) (Rice et al. 2007), and 22% in the general population in 2003/4 (prevalence among resident women aged 15-49 years and men aged 15-54 years) (Welz et al. 2007).

3.2 The Africa Centre Demographic Surveillance System

Started in 2000, the surveillance population includes approximately 86,000 people who are members of around 11,000 households (Tanser et al. 2007). Demographic data on individuals and households in the surveillance area are collected twice annually, and information on births, deaths, changes in marital status, and migration is updated at each round. To reflect the complexity of living arrangements in South Africa, data are collected on both resident and non-resident household members, and the system allows individuals to be reported as members of multiple households (Hosegood, Benzler, and Solarsh 2005; Hosegood and Timæus 2005). The level of participation by households in ACDIS is high - around 99% in each round.

Marriage and partnership data are collected for all adult household members (resident and non-resident members) during bi-annual household visits. Information is provided by each adult member if present, or by a proxy household respondent. Data collected during the previous household visit are pre-printed on the questionnaire, then checked and updated. The questions, codes, and explanatory notes can be accessed at: www.africacentre.ac.za. Briefly stated, the marital status on the day of the visit is recorded for all men and women 18 years or older using a detailed hierarchical coding system. For currently married respondents, information is recorded about whether the marriage has been registered. For couples married by a marriage officer (for example, at a registry office or by a religious leader) registration is automatic. Information is also collected about monogamous and polygamous marriages. Those not currently married are asked whether they have ever been married (widowed, divorced) or are engaged to be married.

ACDIS also collects information about non-marital partnerships. All men and women 15 years and older who are not currently married are asked whether they have a non-marital partner, and if so, to categorise them as a regular or casual partner. The distinction between regular and casual partners is typically based on aspects of commitment, duration, and public recognition. Only one partnership pattern for each person is recorded at routine household visits because of issues of confidentiality involving proxy respondents. A hierarchy is used to code people with multiple concurrent relationships. Currently married people are assigned as having a marital partner and are not asked about regular or casual partners. For unmarried people, a regular partner is preferentially recorded over any concurrent casual partner(s). While information about concurrent partners would provide a more complete understanding of partnering, the collection of such personal and potentially sensitive data is not considered appropriate during routine household visits given that data may be collected from proxy respondents.

Further information is recorded about conjugal relationships i.e. marital or regular partnerships in which both partners are members (resident or non-resident) of the same household. In such cases, the male partner is linked to the female partner, the date of when the relationship started is recorded, and the continuation or dissolution of conjugal relationships is updated at each subsequent visit. These relationship-dyads can be linked to other information about the partners including residential status, employment, and parental relationship to children in the household.

The approach to collecting marriage, partnership, and conjugal relationship data has remained unchanged in all the data collection rounds. From round 4, the marital codes were expanded slightly to increase the level of detail about marriage registration. Additional self-reported marital and partnership data are available for the sub-sample of adults participating in annual, linked HIV and sexual behaviour surveys. During the HIV and sexual behaviour survey interview data are collected that are either more sensitive, e.g. the characteristics of recent sexual partners and the number of life-time sexual partners; or are reliably known only by the individual themselves e.g. age at marriage or age at first sex. In this paper we concentrate on data collected by the routine household surveillance and use linked survey data only when comparing self and proxy reports of marital and partnership status, and age at first marriage.

The fieldworkers who collect the data are full-time Africa Centre employees. Fieldworkers can be male or female, must have passed at least matriculation, are extensively trained upon recruitment as well as receive regular re-training at the beginning of each data collection round, and have daily contact with supervisors during their fieldwork. Data quality is also monitored and enhanced through supervisory and quality control visits.

4. Results

4.1 Marriage patterns

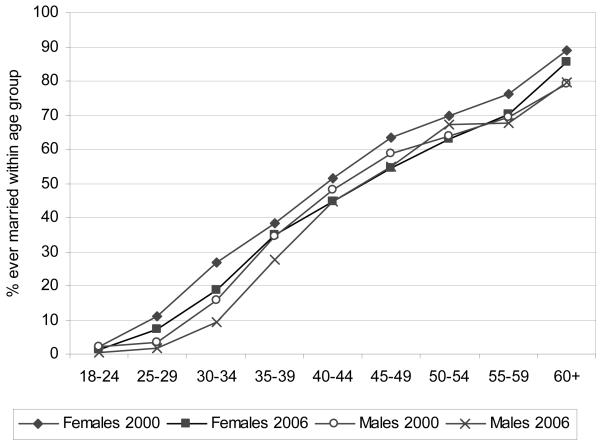

This section describes the characteristics and trends in marriage over fifteen rounds of household surveillance data from 2000-2006. There has been a continued decline in marriage between 2000 and 2006 in the ACDIS population. Figure 1 presents the proportion ever married by age and sex in the first and last years of available data, 2000 and 2006. ACDIS being an open cohort means that the populations in 2000 and 2006 are not identical. The trend by year (not shown) is a small but consistent reduction in the proportion ever married by age and sex for both sexes. There is no discernable marital change in older men aged 50 years and older.

Figure 1. Distribution of ever marriage by sex and age, ACDIS 2000 and 2006.

The reduction in the proportion of married adults in reproductive ages is being largely driven by non-marriage rather than widowhood or divorce despite increasing young adult mortality. Table 1 presents the age-specific marital status among those reported to be currently married in 2000 and 2006. While the proportion of adults that have ever been married has fallen in each age group between 2000 and 2006 (with the exception of men aged 50-54 and 60+ years), the distribution of marital types (currently married, widowed, divorced, and separated) among those ever married has not substantially changed. A more substantial increase in the proportion of widows/widowers in younger age-groups was expected given the high level of AIDS mortality. In a period where antiretroviral treatment was not available in public health facilities, the impact of adult mortality on the rate of widowhood may be masked by the subsequent death of widowed spouses, as well as by re-marriage.

Table 1. Distribution of marital status by age and sex, ACDIS 2000 and 2006.

| Age groups in years |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18-24 | 25-29 | 30-34 | 35-39 | 40-44 | ||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Women, 2000 | ||||||||||

| Never married | 6173 | 99 | 3709 | 89 | 2390 | 73 | 1677 | 62 | 1123 | 49 |

| Ever married, of which: | 62 | 1 | 422 | 11 | 864 | 27 | 1024 | 38 | 1175 | 51 |

| Currently married | 56 | 90 | 387 | 92 | 754 | 87 | 830 | 81 | 881 | 75 |

| Widowed | 3 | 5 | 26 | 6 | 86 | 10 | 143 | 14 | 238 | 20 |

| Divorced | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 20 | 2 | 15 | 1 |

| Separated | 3 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 18 | 2 | 31 | 3 | 41 | 3 |

| Women, 2006 | ||||||||||

| Never married | 6974 | 99 | 3781 | 93 | 2672 | 82 | 1616 | 65 | 1175 | 55 |

| Ever married, of which: | 61 | 1 | 272 | 7 | 598 | 18 | 852 | 35 | 948 | 45 |

| Currently married | 59 | 97 | 263 | 97 | 534 | 89 | 698 | 82 | 697 | 74 |

| Widowed | 2 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 60 | 10 | 132 | 15 | 218 | 23 |

| Divorced | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 12 | 1 |

| Separated | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 2 | 21 | 2 |

| Men, 2000 | ||||||||||

| Never married | 5486 | 100 | 3504 | 98 | 2240 | 85 | 1544 | 66 | 975 | 52 |

| Ever married, of which: | 6 | 0 | 84 | 2 | 409 | 15 | 804 | 34 | 886 | 48 |

| Currently married | 4 | 67 | 81 | 96 | 393 | 96 | 773 | 96 | 837 | 94 |

| Widowed | 1 | 17 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 12 | 1 | 22 | 2 |

| Divorced | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| Separated | 1 | 17 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 13 | 2 | 23 | 3 |

| Men, 2006 | ||||||||||

| Never married | 6712 | 100 | 3708 | 99 | 2508 | 91 | 1442 | 73 | 947 | 56 |

| Ever married, of which: | 6 | 0 | 54 | 1 | 252 | 9 | 544 | 27 | 755 | 44 |

| Currently married | 4 | 67 | 49 | 91 | 249 | 99 | 523 | 96 | 719 | 95 |

| Widowed | 1 | 17 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 13 | 2 | 24 | 3 |

| Divorced | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 |

| Separated | 1 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 7 | 1 |

| Age groups in years |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45-49 | 50-54 | 55-59 | 60+ | Total | ||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Women, 2000 | ||||||||||

| Never married | 502 | 37 | 387 | 31 | 226 | 24 | 357 | 11 | 16544 | 65 |

| Ever married, of which: | 866 | 63 | 881 | 69 | 721 | 76 | 2904 | 89 | 8919 | 35 |

| Currently married | 590 | 68 | 547 | 62 | 390 | 54 | 805 | 28 | 5240 | 59 |

| Widowed | 218 | 25 | 283 | 32 | 298 | 41 | 2002 | 69 | 3297 | 37 |

| Divorced | 17 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 14 | 2 | 20 | 1 | 104 | 1 |

| Separated | 41 | 5 | 41 | 5 | 19 | 3 | 77 | 3 | 278 | 3 |

| Women, 2006 | ||||||||||

| Never married | 858 | 46 | 454 | 37 | 326 | 30 | 472 | 14 | 18328 | 69 |

| Ever married, of which: | 1017 | 54 | 765 | 63 | 757 | 70 | 2816 | 86 | 8086 | 31 |

| Currently married | 697 | 69 | 456 | 60 | 378 | 50 | 720 | 26 | 4502 | 56 |

| Widowed | 282 | 28 | 275 | 36 | 351 | 46 | 2033 | 72 | 3362 | 42 |

| Divorced | 12 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 16 | 1 | 67 | 1 |

| Separated | 26 | 3 | 26 | 3 | 21 | 3 | 47 | 2 | 155 | 2 |

| Men, 2000 | ||||||||||

| Never married | 593 | 41 | 380 | 36 | 242 | 31 | 406 | 21 | 15370 | 72 |

| Ever married, of which: | 842 | 59 | 664 | 64 | 546 | 69 | 1542 | 79 | 5783 | 28 |

| Currently married | 800 | 95 | 611 | 92 | 504 | 92 | 1354 | 88 | 5357 | 93 |

| Widowed | 26 | 3 | 33 | 5 | 35 | 6 | 158 | 10 | 296 | 5 |

| Divorced | 2 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 31 | 1 |

| Separated | 14 | 2 | 15 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 20 | 1 | 99 | 2 |

| Men, 2000 | ||||||||||

| Never married | 632 | 45 | 351 | 33 | 251 | 32 | 368 | 20 | 16919 | 77 |

| Ever married, of which: | 764 | 55 | 723 | 67 | 522 | 68 | 1434 | 80 | 5054 | 23 |

| Currently married | 716 | 94 | 670 | 93 | 486 | 93 | 1264 | 88 | 4680 | 93 |

| Widowed | 35 | 5 | 38 | 5 | 32 | 6 | 158 | 11 | 307 | 6 |

| Divorced | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 0 |

| Separated | 11 | 1 | 14 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 56 | 1 |

Few adults are reported as divorced or separated, the proportion not rising above five percent in any age group. The low rate of divorce in the ACDIS population likely reflects the high proportion of marriages contracted through customary rites. Prior to 1998, marriages contracted under the Customary Marriage Act could be dissolved by a tribal court. However, in practice this was rarely done given the complexity of the marriage process and attendant payments between families, barriers to litigation by women, and traditional customs that allowed men to take additional wives. We might also expect an under-reporting of divorce, particularly in families whose faith tradition does not permit divorce.

In ACDIS, the proportion of married women and men whose marriages were registered rose from 72% in 2002 to 76% in 2006. Registration has been popular among recently married couples. While 91% of married people aged 25-34 years were reported to have registered their marriage, only 60% of married people aged 60 years and older had done so. The youngest age group, 18-24 years, also had a lower rate of marriage registration. This might be expected if young couples have not yet had children, are less adroit at interacting with civil authorities, or are part of a minority religious group who permits marriage to partners younger than 18 years.

4.2 Polygamous marriages

Although there is a tradition of polygamous marriage in Zulu society (de Haas 1984), the majority of marriages in ACDIS 2000-2006 were reported to be monogamous. Polygamous marriages constitute 12% of all marriages in women and 14% in men in 2006. The level of polygamy is higher than that found in the 1998 South African DHS (KwaZulu-Natal sub-sample) where 7% of married African women reported that their husbands have other wives. Polygamous marriages are, as expected, highest in the oldest age group. In ACDIS, 25% of all currently married women and 29% of currently married men aged 60 years and older in 2006 are in polygamous marriages. The prevalence of polygamy is declining across all age groups though it remains higher than in the country as a whole, bolstered in part by the influence of the Shembe religion in the province, an African-initiated religion that both permits, and favourably views, polygamous marriages (Krige 1965). The majority of households are not expected to report polygamously married members given that they follow religious traditions that do not permit polygamous marriages. However, in qualitative research conducted in the same area, we have occasionally observed men reporting non-marital partners as additional ‘wives’. While the majority of marriages in the ACDIS population are now civilly registered, the opposite is true of polygamous marriages despite provision being made for such marriages in the Marriage Act. Only 30% of women whose husbands have other wives are in registered marriages. The low rate of polygamous marriage registration may reflect a disinclination on the part of some groups to engage with statutory regulatory systems in general; but may also be influenced by the higher prevalence of polygamous marriages among older people.

4.3 Age at first marriage

Data on the age of first marriage are available in ACDIS from 2005 for married women (18-49 years) and men (18-54 years) who participated in the ACDIS annual general health survey. In 2005, the median age was 25 years in women (inter-quartile range 21-30 years) and 31 years in men (inter-quartile range 27-35 years). Because of the restricted upper age limit in this group, the estimates may under-estimate slightly the age of first marriage among all married people in the population. If marriage occurs, it happens late. Period estimates of the mean age at first marriage from national administrative data have been reported as 30 years for women and 34 years for men (Statistics South Africa 2000).

4.4 Partnership patterns

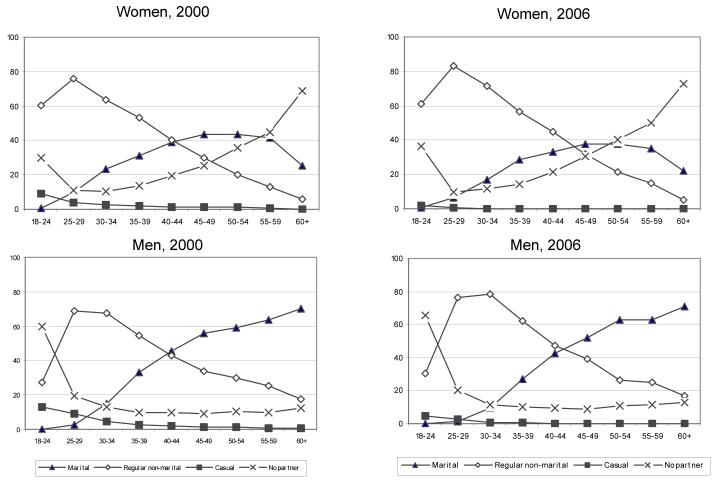

Low rates of marriage in the ACDIS population are offset by high rates of non-marital partnerships. The age-specific patterns of non-marital partnerships in 2000 and 2006 are shown in Figure 2. The pattern of non-marital regular partnerships has maintained the same general age-specific pattern but has risen year to year between 2000 and 2006. By 2006, the majority of unmarried women (63%) and men (63%) 18 years and older are reported to have had a regular partner or casual partner. The proportion of younger adults reporting having a casual partner(s) fell by half between 2000 and 2006. It would be rash to use these data in isolation as evidence of a substantive change in casual sexual partners given that it might also arise from an increasing avoidance of reporting ‘casual’ partners (desirability bias).

Figure 2. Partnership patterns by age and sex, ACDIS population 2000 and 2006 1.

1 At each routine household visit, ACDIS records one partnership pattern for each person. A hierarchy is used to code people with concurrent relationships. Currently married people are assigned as having a marital partner and are not asked about regular or casual partners. For unmarried people, a regular partner is preferentially recorded over any concurrent casual partner(s).

4.5 Household and residential arrangements of partners

The very high level of migration in this part of South Africa creates a context in which many married couples live apart. Therefore, cohabitation is one, but not the only, indicator of social connectedness between partners. In ACIDS, cohabitation arrangements are recorded separately from the indicator that the couple are in a ‘conjugal relationship’, meaning that both partners are considered to be a member of the same household (regardless of whether they are resident or non-resident). A diverse set of arrangements may exist. A married couple may be considered to be members of the same household even though one spouse is working and living elsewhere. Unmarried partners may not be reported as members of each other’s rural household even though they co-habit in the place to which they migrate for work. Table 2 shows the proportion of conjugal relationships for all resident women and men reporting a marital or non-marital relationship in 2006. Amongst the youngest age group, few partners are considered to be a member of the same household. Although older people are more likely to have a conjugal partner, the proportion is still less than half even amongst women and men aged 30-34 years. In the lower section of Table 2, we present more detailed data on social and residential arrangements by marital status in women. We do not present the data about the partner’s residential status for men given that it is complicated by polygamous relationships.

Table 2. Distribution of conjugal relationship in women by marital status, partnership status and male partner’s co-residency (number and percentage). ACDIS, 2006.

| Age groups in years |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18-24 | 25-29 | 30-34 | 35-39 | 40-45 | 45-49 | 50-54 | 55-59 | 60+ | all ages | |

|

|

||||||||||

| Marital or partnership pattern | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n |

|

|

||||||||||

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| Number of resident women (total) | 3889 | 1907 | 1704 | 1524 | 1458 | 1436 | 1002 | 943 | 3044 | 16907 |

| Number of resident women with a marital or regular partner | 2462 | 1699 | 1478 | 1275 | 1128 | 1002 | 589 | 474 | 823 | 10930 |

| Of women with a marital or regular partner1: | ||||||||||

| Proportion with a conjugal partner (resident or non-resident) |

155 (6.30) | 358 (21.07) | 558 (37.75) | 709 (55.61) | 721 (63.92) | 739 (73.75) | 440 (74.70) | 357 (75.32) | 586 (71.20) | 4623 (42.30) |

| Proportion of conjugal unions with a resident male partner2 |

100 (67.57) | 229 (66.76) | 325 (60.30) | 420 (60.43) | 438 (61.60) | 472 (64.92) | 297 (68.91) | 244 (69.12) | 491 (84.80) | 3016 (66.64) |

| Of married women only: | ||||||||||

| Proportion with a conjugal partner (resident or non-resident) |

15 (57.69) | 114 (86.36) | 282 (83.19) | 471 (86.58) | 511 (85.74) | 542 (87.14) | 354 (86.34) | 298 (84.66) | 516 (75.00) | 3103 (83.66) |

| Proportion of conjugal unions with a resident male partner |

11 (78.57) | 68 (60.71) | 168 (60.43) | 260 (55.91) | 288 (56.80) | 334 (62.08) | 234 (66.86) | 207 (69.70) | 437 (85.35) | 2007 (65.31) |

| Of women in an unmarried regular partnership only: | ||||||||||

| Proportion with a conjugal partner (resident or non-resident) |

140 (5.75) | 244 (15.57) | 276 (24.23) | 238 (32.56) | 210 (39.47) | 197 (51.84) | 86 (48.04) | 59 (48.36) | 70 (51.85) | 1520 (21.05) |

| Proportion of conjugal unions with a resident male partner |

89 (66.42) | 161 (69.70) | 157 (60.15) | 160 (69.57) | 150 (72.53) | 138 (73.02) | 63 (77.78) | 37 (66.07) | 54 (80.60) | 1009 (69.44) |

| Of women in an unmarried regular partnership only (by residence) | ||||||||||

| Proportion with a conjugal partner (resident or non-resident) among women resident in a peri-urban or urban area |

64 (7.87) | 119 (19.77) | 125 (26.48) | 93 (30.49) | 99 (40.08) | 75 (50.68) | 34 (50.75) | 17 (39.53) | 27 (39.53) | 653 (23.75) |

| Proportion with a conjugal partner resident or non-resident) among women resident in a rural area |

76 (4.68) | 125 (12.95) | 151 (22.64) | 145 (34.04) | 111 (38.95) | 122 (52.59) | 52 (46.43) | 42 (53.16) | 43 (51.81) | 867 (19.39) |

In ACDIS, a conjugal relationship can only be recorded for adults (>15 years old) reported to be currently in a marital or regular partnership. We have restricted the sample presented in this table to people aged 18 years and older for consistency with marital status. There are very few non-marital conjugal relationships reported for people less than 18 years of age.

In each column, the denominator for the proportion of conjugal unions with a resident male partner is the number of women with a conjugal partner irrespective of their partner's residency status. For example, 155 resident women aged 18-24 years reported being a conjugal relationship with a member of the same household. Of these, 100 women (67.57%) had a resident male partner.

Although non-marital partnerships are very common, social norms around kinship and family formation appear to remain a barrier to the social acceptance of non-marital partners as part of their partners’ household. While the majority of married men (92%) are members of the same household as their wife, only one-third (33%) of unmarried male partners are considered to belong to their partners’ household (Table 2). However, there is a pronounced difference by age. Among older unmarried couples there is a greater recognition of the couple as belonging to the same household although it remains less common than among married couples. These unmarried conjugal couples are likely to be in longer-term relationships. In many cases the couple will have borne or raised children together, probably established their own household, and have co-habited at some time. Thus, despite their lack of marriage, they have created a recognizable social arrangement. This level of social recognition is much harder for younger, unmarried couples to achieve, particularly when one or both partners are still living in a parental or kin-headed household.

In understanding changes in family formation and building, parenting and economic livelihoods, it is important to know whether the increasing proportion of non-marital unions are different in terms of their residential arrangements to the marital unions they are replacing. Amongst those couples considered to have a social connection (conjugal relationship), cohabitation is actually more common among unmarried than among married couples in all age groups except 18-24 years (Table 2). Co-residence may enhance the perception that an unmarried couple has formed their own household, whereas for married couples, social recognition is a function of their marriage regardless of their cohabitation. Overall, in ACDIS since 2000, the proportion of women in a marital or regular partnership whose partner is a member of the same household has declined from 55%, to 51% in 2003, and 42% in 2006.

The study area, while predominantly rural, includes urban and peri-urban areas in whose communities one might expect to find a higher proportion of people with non-traditional partnerships. Table 3 presents the marital and conjugal relationship data separately for resident women in urban/peri-urban and rural areas. For age groups 40 years and older, the proportion of never married women in each age group is statistically different (p<0.05) between the two types of areas, with a significantly higher proportion (10-15% more) of urban/peri-urban women never married compared with women living in rural areas. Significant differences are observed in the proportion in a conjugal relationship only for the youngest two age groups of unmarried women. Young unmarried in urban/peri-urban areas were significantly more likely than their rural equivalents to be in a conjugal relationship, with the difference being largest in age group 25-29 years, of whom 20% of unmarried women living in the urban/peri-urban area reported a conjugal partner compared with 13% in rural areas.

Table 3. Distribution of never marriage and non-marital conjugal relationships in resident women by area and age (number and percentage), ACDIS, 2006.

| Age groups in years |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18-24 | 25-29 | 30-34 | 35-39 | 40-45 | 45-49 | 50-54 | 55-59 | 60+ | all ages | |

|

|

||||||||||

| Marital or partnership pattern | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n |

|

|

||||||||||

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| Of women resident in peri-urban or urban areas1: |

||||||||||

| Proportion never married2 | 1293 (98.78) | 708 (93.04) | 570 (76.31) | 376 (56.97) | 307 (49.68) | 241 (49.69) | 130 (41.40) | 116 (36.36) | 186 (23.11) | 3927 (65.25) |

| Of women resident in a rural area: | ||||||||||

| Proportion never married | 2648 (98.92) | 1085 (92.26) | 766 (78.56) | 499 (56.64) | 363 (42.41) | 320 (33.23) | 198 (28.49) | 135 (21.57) | 233 (10.34) | 6247 (56.26) |

| Of women in an unmarried regular partnership and resident in a peri-urban or urban area: |

||||||||||

| Proportion with a conjugal partner (resident or non-resident)3 |

64 (7.87) | 119 (19.77) | 125 (26.48) | 93 (30.49) | 99 (40.08) | 75 (50.68) | 34 (50.75) | 17 (39.53) | 27 (39.53) | 653 (23.75) |

| Of women in an unmarried regular partnership and resident in a rural area: |

||||||||||

| Proportion with a conjugal partner resident or non-resident) |

76 (4.68) | 125 (12.95) | 151 (22.64) | 145 (34.04) | 111 (38.95) | 122 (52.59) | 52 (46.43) | 42 (53.16) | 43 (51.81) | 867 (19.39) |

An urban homestead lies within the municipal authority boundaries; a peri-urban area is classified by ACIDS on the basis of a population density of more than 400 people per km2.

The difference between the proportions of resident women never married in the two types of area was statistically significant (chi-squared test value p<0.05) for all age groups 40+ years and older.

The difference between the proportions of resident unmarried women with a conjugal partner in the two types of area was statistically significant (chi-squared test value p<0.05) for the youngest age-groups (18-24 and 25-29 years) only.

4.6 Consistency of reporting of marriage data in ACDIS

One means of verifying the consistency of reporting in ACDIS is to compare marital data from self- and household proxy reports. Routine data collection about the marital and partnership status of household members is conducted during the bi-annual household update visit. At household visits, where members are absent, knowledgeable household respondents will provide updates on other members. The identities of household respondents are recorded at each visit. To examine the extent to which proxy respondent reports match self-reports, we compare the agreement between self-reported marital status collected during the general health questionnaire administered to all resident adults (women aged 15-49 years, men aged 15-54 years), and the closest marital status report on the same person reported during a routine ACDIS data collection visit from a proxy household respondent (Table 4). The level of agreement regarding marital status between self and household respondents for those never married is high. Only in the oldest age groups (45-49 years in women, 50-54 years in men) is there more than a 10% difference, thereby supporting our contention that the data demonstrate consistency in the way that marital data is operationalised in ACDIS, and that there is no evidence of substantive social desirability bias in reports of marriage in this population. Of women self-reporting as never married, but not reported as such by household respondents, roughly equal numbers had been reported to be currently married or widows. For never married men (by self report) where there is a difference in household report, almost all were reported to be currently married.

Table 4. Agreement between self-reports of never married with report by household respondent other than self, by age and sex. ACDIS, 20051.

| Age group |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reporting of never married | 18-24 | 25-29 | 30-34 | 35-39 | 40-44 | 45-49 | 50-54 |

| Women | |||||||

| Number self-reported to be never married (N) |

1845 | 544 | 346 | 221 | 220 | 169 | - |

| n (%) reported to be never married by a different household respondent |

1841 (99.8) | 539 (99.1) | 337 (97.4) | 210 (95.0) | 205 (93.2) | 141 (83.4) | - |

| Men | |||||||

| Number self-reported to be never married (N) |

1868 | 409 | 272 | 182 | 130 | 105 | 61 |

| % reported to be never married by a different household respondent |

1868 (100) | 405 (99.0) | 270 (99.3) | 176 (96.7) | 123 (94.6) | 101 (96.2) | 54 (88.5) |

Self-reported martial status obtained from the ACDIS general health survey in 2005 (women 15-49 years, men 15-54 years). Household respondent (i.e. not self) report of marital status from routine ACDIS visit in round 2, 2005.

The younger age group in the general health survey makes it less valuable as a way of comparing reports of widowhood. Only three men in the general health survey reported being widowers. Among women in the survey, widowhood reports agreed for 78% in 35-39 years, 86% in 40-44 years, and 88% in 45-49 years.

5. Conclusions

The fifteen rounds of population-based surveillance data show that the declines in marriage in KwaZulu-Natal identified in the 1960s have not been reversed but rather the proportion of the adult population ever married has continued to decline between 2000 and 2006. For a large proportion of young couples, the perceived costs of marriage appear to outweigh the benefits, and the limited sanctions against extra-marital childbearing in many families reduce marriage as a necessary entry to parenting. The factors ranged against marriage appear to foster cautiousness in starting, and a lack of haste in finishing, the marriage process. Waiting for the ‘right’ time to marry, means waiting for the right partner as well as more education, work, income, housing etc. For many young adults in rural KwaZulu-Natal, the desired constellation of circumstances does not, it seems, come in to line. A scenario in which, while there are many hurdles placed in the way, marriage is not completely ruled out fits closely with ethnographic studies that show that even while rates of marriage are low, marriage remains a highly prized life-event - one that is desired and anticipated by young adults (Preston-Whyte and Zondi 1992).

However, while we have highlighted the continued declines in marriage, it would be misleading to suggest that marriage is moribund in this population. In the study population, around half of all women and men 45 years and older have been married. A large number of couples continue to embark upon the process of ilobolo or become engaged, going on to marry in both traditional and civil ceremonies. As we show, those marrying, marry late, with a median age of first marriage of 25 years in women and 31 years in men. Data on trends in the age at first marriage are not yet available for this population. There have also been changes in the way that marriages are contracted. The proportion of married women and men choosing to register their marriages also rose from 72% in 2002 to 76% in 2006, registration being most popular among recently wed couples.

The ACDIS data suggest that declines in marriage have not been accompanied by a strong transition towards non-marital cohabiting unions, particularly in rural areas. One may speculate about why this may be. One of the key issues is that co-residence in southern African rural populations is not a defining characteristic of either conjugal unions or of household units. In the Western tradition, starting to live together is an event in its own right, one marking the start of a public and more intimate phase of their conjugal relationship. In contrast, in KwaZulu-Natal, the legacy of labour migration and barriers to free movement of families means that cohabitation is not seen as a necessary signifier of either a marital or non-marital partnership. In ACDIS, even among resident married women, 35% had a non-cohabiting spouse. In her 2003 paper tracing the distinctive roots of Western and African households, Margo Russell challenges the assumption that African South Africans are engaged in a transition to a Western pattern of non-marital cohabiting unions and writes: “A moment’s thought would confirm the profoundly different weight placed on conjugal co-residence by black and white people. Romantic-love-based Western marriage prescribes a shared conjugal household; a marriage contracted within a polygynous idiom against a background of patrilineal extended families long accustomed to migrant labour, is subject to very different expectations.” (Russell 2003:9).

The difference in the distribution of marital and partnership patterns observed between women resident urban/peri-urban and rural areas in some age groups suggests that aggregate population data, even in a relatively small, predominantly rural area, may mask heterogeneity between communities. For older women, it is not possible with the available data to determine whether these differences are due to the long-term community-level influences on marriage or result from selective migration of women with these marital and partnership characteristics to or from particular areas. In younger cohorts, longitudinal analyses of community-level correlates of partnership formation, marriage and migration warrants further investigation.

It has been suggested that African marriage and childbearing patterns in South Africa, particularly in KwaZulu-Natal, have come to closely resemble those of the Caribbean in terms of low rates of marriage, high rates of extra-marital childbearing, and a high proportion of female-headed households (Preston-Whyte 1988; Van de Walle 1993). However, in 2000, the ACDIS data showed that only 7% of never married women headed their own households and only one-third lived in a household headed by a woman. A second key difference between the two regions relates to migration. Although co-residential conjugal unions are the basis of family organisation in most parts of the world, many people in KwaZulu-Natal will not experience extensive periods of cohabitation with their married or unmarried partners. Qualitative research conducted in the study population suggests that the extent to which their separate households are inter-connected may have an important role in shaping the quality, stability and future evolution of non-conjugal relationships (Hosegood et al. 2007). However, the ability to consistently link and update relationships between households is limited in a large population-based survey.

The ACDIS marriage and partnership data are of high quality. The repeated updated data collected by well-trained and supervised fieldworkers using the same questions and coding, generates data with good individual and population validity and consistency. In the appendix we map the ACDIS marriage, residential and conjugal relationships data onto the smaller number of categories in the 2001 South African Census (see appendix). The comparison highlights how reporting of marriage and partnership can vary markedly depending on the wording of the question, the instructions given to interviewers, and the interpretation of respondents. Other authors have noted other weaknesses in the assumptions and interpretations of South African survey data on marriage and households (Budlender, Chobokoane, and Simelane 2005; Russell 2003; Ziehl 1999). However, the implication of the cohabitation findings presented in this paper raises important concerns about the increasing use of the broad and ill-defined term ‘living together’ by censuses, the demographic and health surveys, and other household surveys in South Africa. Using a ‘square peg forced into a round hole’ approach to classify the diversity of unmarried unions in South Africa lacks imagination, as well as creates overlapping marital status categories. However, based on the experience of ACDIS, we do not agree with commentators who have suggested that, because marriage in Africa is frequently a long process rather than a single event, surveys should use a longer set of questions ascertaining which stage among many a person has reached (see for example, (Meekers 1992; Speizer 1995). Whilst this kind of detail can be important in ethnographic research, we feel that in population surveys and censuses respondent-reported marital status, particularly when self-reported, remains the most appropriate classification.

The analysis described in this paper provides a first description of marriage and partnership patterns and trends in this population. Further studies are needed; for example, to understand the determinants and dynamics of marriage and partnership in this study population using analyses of individual life-courses rather than repeated cross-sectional data. The data also can be used to explore the role of marital and non-marital partnerships in determining HIV transmission dynamics and risk. While these are beyond the scope of this paper, we have demonstrated several important strengths of the detailed, longitudinal, population-based data collected by ACDIS for research on marriage and cohabitation.

Acknowledgements

The population-based HIV survey and Africa Centre Demographic Information System (ACDIS) were supported by The Wellcome Trust, UK grants no. 65377 and no. 50535 to the Africa Centre for Health and Population Studies; and grants to Hosegood (GR082599MA) and McGrath (WT083495MA). We thank the ACDIS staff and the Africa Centre Population Studies group for the work that makes such papers possible. We also gratefully acknowledge Eleanor Preston-Whyte – her scholarship on Zulu marriage, her support for ACDIS since its inception, and her collaboration have been invaluable. We appreciate the helpful comments of the anonymous reviewers whose insight and suggestions have enhanced this paper.

Appendix

Comparison of ACDIS data with other survey and census data

Census data is a commonly used source of marriage and partnership data in South Africa. Examination of the trends and patterns reported by ACDIS relative to data for rural KwaZulu-Natal from the censuses allows us to consider the effect of different data collection strategies on reported marriage patterns. One might postulate that longitudinal surveys obtain more accurate reports than cross-sectional surveys and censuses for a number of reasons. With strong positive social norms about marriage, social desirability can be a reason for reporting bias in one-off interviews. Respondents and/or interviewers may be expected to over-report marital unions, for example, a parent of a co-habiting woman with young children may feel more comfortable reporting that their daughter is married; or an interviewer may assume that older respondents must have been or are married rather than asking them directly. In contrast, longitudinal studies can potentially obtain a more accurate view of respondents’ social and legal situations. In addition, ACDIS has more scope to collect more information about aspects of marriage and partnerships than is possible in a national census.

The direct comparison of these two sources of data is not straight forward. The main challenge is that recent South African censuses, as well as several other national surveys, blur the concept of ‘marriage’ and ‘cohabitation’, whereas these phenomena are distinguished in ACDIS. The 2001 Census uses the following marital status categories: never married, married civil/religious, married traditional/customary, polygamously married, living together as unmarried partners, widow/widower, and divorced. However, ‘living together’ is not in reality a marital state but rather a description given to unmarried relationships based on perceptions about the nature of their relationship and residential arrangements. Understanding the use of this term in South Africa is complicated by high residential mobility and separation of couples due to labour migration. Thus, depending on how the term is translated and understood, an unmarried woman in a long-term conjugal relationship might describe herself as ‘living together’ even though her partner works and lives elsewhere. Given the lack of a hierarchical set of categories it is also unclear whether people would select the ‘living together’ classification over those related to their marital status such as saying that they are widowed, divorced or never married.

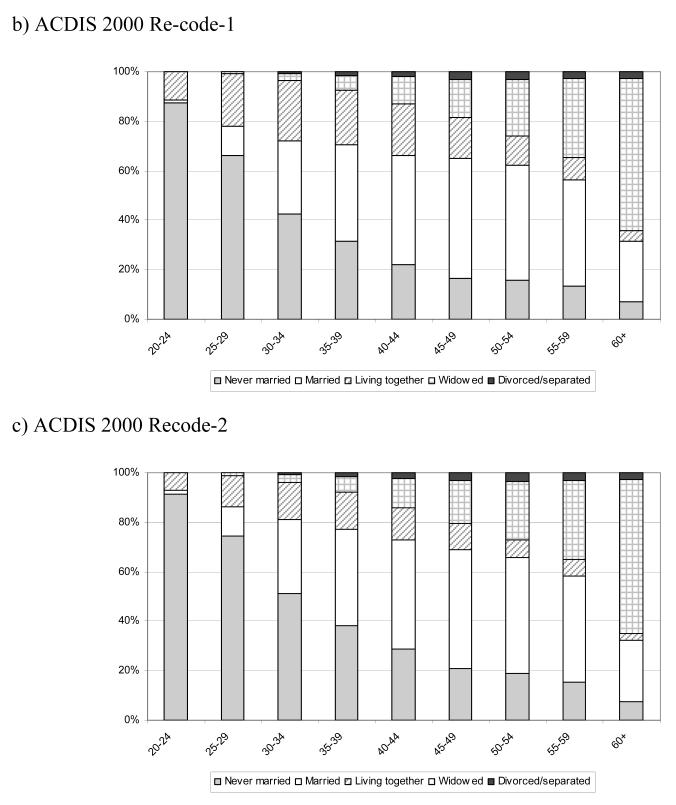

In examining how the ACDIS categories map on to those of the 2001 Census, the main challenge is to reclassify ACDIS data to obtain a ‘living together’ category which may approximate the way that the Census was interpreted in the field. We present two different reclassifications of the ACDIS for women observed in 2000. In Recode-1 women who are not currently married (never married, widowed, divorced and separated) are classified as ‘living together’ if their partner is a member of the same household (i.e. has a conjugal relationship), regardless of whether their partner is cohabiting or not. Recode-2 emphasises the co-residency dimension and classifies women as ‘living together’ if they are not currently married and have a resident conjugal partner. We do not show a similar comparison for men because of the complexity introduced by polygamous unions. The 10% sample of the Census sample does not permit the exclusion of polygamous men. However, from the ACDIS data we know that their living arrangements can be very complex involving multiple conjugal partners in the same or different households, thus creating more uncertainty about how to simulate the Census data in men.

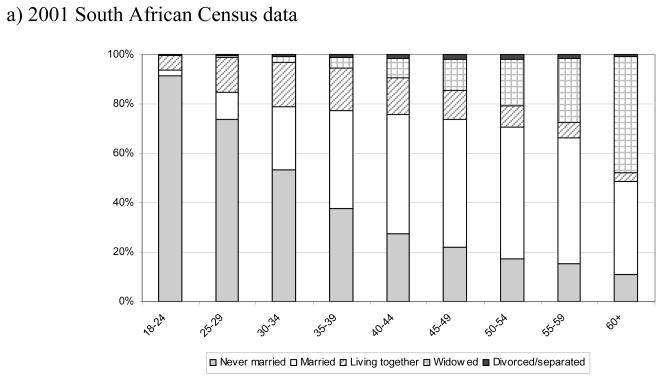

Marital status from the 2001 Census and ACDIS 2000 are shown in Figures 3a-c. The level and pattern of never married are remarkably similar in both sources providing strong evidence that non-marriage has become entrenched in rural KwaZulu-Natal. It also suggests that reporting of non-marriage is consistent across different types of survey design, as well as being robust despite the lack of specific instructions about the question to enumerators in the 2001 Census. Whilst someone who has married may be unsure about whether to report their current or past status, someone who is never married need only choose between ‘never married’ and the ‘living together’ category.

Figure 3. Age-specific marital patterns in women 20 years and older1 from a) the 2001 South African Census for rural KwaZulu Natal, b) ACDIS 2000 using Re-code 12, c) ACDIS 2000 using Re-code 23.

Notes:

1 The 10% sample of the 1996 Census is available only in five-year age groups.

2 Recode-1 classifies women resident in the second round of ACDIS (2000) as ‘living together’ providing that they are not currently married (never married, widowed, divorced and separated), and their partner was a member of the same household (resident or non-resident).

3 Recode-2 classifies women as ‘living together’ only if they are not currently married and have a co-resident partner in the same household.

The proportion ‘living together’ is more closely approximated in ACDIS by selecting only women whose non-marital conjugal partners are co-resident (Re-code-2). Thus, the Census obscures the existence of some 10% of young couples who whilst being recognised as being members of the same household have one of them living somewhere else. This raises the question about the appropriateness of translating the term ‘living together’ from high income countries to a South African context with high residential mobility.

The main difference between the two sources of data is a higher reporting of female widowhood in ACDIS than in the Census, particularly in the oldest age groups. The proportion of widows in ACDIS is twice that of the Census in women after age 60 years. Can we establish whether one data source more accurately represents the true marital status data in this population? In ACDIS, the marital types among ever married women are very consistent year on year. The proportion of widows at older ages shows a slight percentage reduction each year which is to be expected as successive cohorts have a decrease in the proportion ever married. In comparison, the proportion of widows among women (60 years and older) who have ever been married fluctuates across the last three South African censuses from 50% in 1970 to 31% in 1996 and 49% in 2001. The 1996 data for all age groups appears to be improbably low. We suggest that in the ACDIS population, the long-established pattern of high rates of non-marriage reduces the social desirability to over-report marriage and by extension, widowhood. We have qualitative experience of obtaining information from different respondents that suggests that marital status may be re-evaluated in the light of subsequent events (Hosegood and Preston-Whyte 2002). For example, older women may re-define themselves as never married because their marital union had dissolved. Such a re-evaluation may be most readily done when a former partner fails to complete ilobolo or recognise his children. Similar changes in reporting by older people have also been reported in surveys in Tanzania (Nnko et al 2004). Why would this behaviour be less prevalent in ACDIS than in the Census? We suggest that the combination of the relationship between participants and fieldworkers built up during repeated visits and the clear instructions to fieldworkers and distinct questions about marital status, partnership patterns and living arrangements, increases the reliability of reporting about past as well as present marital status. On the negative account, ACDIS’ smaller sample size, particularly at the oldest age groups, will mean that the ACDIS estimates for the less common marital states such as widowhood and divorce will be less precise (i.e. wider confidence intervals) than those obtained from the Census.

References

- Bärnighausen T, Hosegood V, Timæus IM, Newell M. The socioeconomic determinants of HIV incidence: a population-based study in rural South Africa. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 7):S29–S38. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000300533.59483.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozzoli B. The Meaning of Informal Work: Some Women’s Stories. In: Preston-Whyte E, Rogerson C, editors. South African Informal Economy. Oxford University Press; Cape Town: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Budlender D, Chobokoane N, Simelane S. Marriage patterns in South Africa: methodological and substantive issues. Southern African Journal of Demography. 2005;9(1):1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Burman S, Preston-Whyte E. Assessing illegitimacy in South Africa. In: Burman S, Preston-Whyte E, editors. Questionable Issue: Ilegitimacy in South Africa. Oxford University Press; Cape Town: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Burman S, van der Werff N. Rethinking customary law on bridewealth. Social Dynamics. 1993;19(2):111–127. doi:10.1080/02533959308458554. [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Ardington C. In: Socioeconomic Factors. Population Studies working group, editor. Africa Centre for Health and Population Studies monograph; Mtubatuba: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cassim NA. Some reflections on the Natal Code. Journal of African Law. 1981;25(2):131–135. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers DL. Civilizing the natives: Marriage in post-apartheid South Africa. Daedalus. 2000;129(4):101–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crankshaw O. A simple questionnaire survey method for studying migration and residential displacement in informal settlements in South Africa. SA Sociological Review. 1993;6(1):52–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haas M. Changing Patterns of Black Marriage and Divorce in Durban. Department of Social Anthropology, Faculty of Social Science, University of Natal; Durban: 1984. PhD thesis. [Google Scholar]

- de Haas M. Is there anything more to say about lobolo? African Studies. 1987;46(1):33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Dorrington R, Johnson L, Bradshaw D, Daniel T. The Demographic Impact of HIV/AIDS in South Africa. Centre for Actuarial Research, South African Medical Research Council and Actuarial Society of South Africa report; Cape Town: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gluckman M. Kinship and Marriage among the Lozi of Northern Rhodesia and the Zulu of Natal. In: Radcliffe-Brown AR, Forde D, editors. African Systems of Kinship and Marriage. Routledge and Kegan Paul; London: 1950. pp. 166–206. [Google Scholar]

- Goody J. Bridewealth and dowry. Cambridge University Press; London: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood-Lejeune A. Rising age at marriage and fertility in Southern and Eastern Africa. European Journal of Population. 2000;17:261–280. doi:10.1023/A:1011845127339. [Google Scholar]

- Heuveline P. Impact of the HIV epidemic on population and household structure: the dynamics and evidence to date. AIDS. 2004;18(Suppl. 2):S45–S53. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200406002-00006. doi:10.1097/00002030-200406002-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosegood V, Benzler J, Solarsh G. Population mobility and household dynamics in rural South Africa: implications for demographic and health research. Southern African Journal of Demography. 2005;10(1&2):43–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hosegood V, Preston-Whyte E. Marriage and partnership patterns in rural KwaZulu Natal; Paper presented at the Population Association of America Conference; Atlanta, USA. 2002.May 8-11, [Google Scholar]

- Hosegood V, McGrath N, Herbst K, Timæus IM. The impact of adult mortality on household dissolution and migration in rural South Africa. AIDS. 2004;18(11):1585–1590. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000131360.37210.92. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000131360.37210.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosegood V, Preston-Whyte E, Busza J, Moitse S, Timæus IM. Revealing the full extent of households’ experience of HIV and AIDS in rural South Africa. Social Science and Medicine. 2007;65:1249–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.002. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosegood V, Timæus IM. Household Composition and Dynamics in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa: Mirroring Social Reality in Longitudinal Data Collection. In: van der Walle E, editor. African Households: an exploration of census data. M.E. Sharpe Inc.; New York: 2005. pp. 58–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter M. Fathers without amandla: Zulu-speaking men and fatherhood. In: Morrell R, Richter L, editors. Baba: Men and Fatherhood in South Africa. HSRC Press; Cape Town: 2006. pp. 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Jones S. Children on the move: parenting, mobility, and birth-status among migrants. In: Burman S, Preston-Whyte E, editors. Questionable Issue: Illegitimacy in South Africa. Oxford University Press; Cape Town: 1992. pp. 247–281. [Google Scholar]

- Jones S. Assaulting Childhood. Children’s Experiences of Migrancy and Hostel Life in South Africa. Witwatersrand University Press; Johannesburg: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Krige EJ. The Social System of the Zulus. Shuter and Shooter; Pietermaritzburg: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Lesthaeghe R, Jolly C. The start of the sub-Saharan fertility transition: some answers and many questions. Journal of International Development. 1995;7:25–45. doi:10.1002/jid.3380070103. [Google Scholar]

- Locoh T. Evolution of the Family in Africa. In: van de Walle E, Sala-Diakanda MD, Ohadike PO, editors. The State of African Demography. IUSSP; Liege: 1988. pp. 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Maharaj B. The ‘Spatial’ Impress of the Central and Local States: The Group Areas Act in Durban. In: Smith DM, editor. The Apartheid City and Beyond: Urbanization and Social Change in South Africa. Routledge; London and New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer P. Black Villagers in an Industrial Society. Anthropological Perspectives on Labour Migration in South Africa. Oxford University Press; Cape Town: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- McClendon T. Generating Change, Engendering Tradition. Rural Dynamics and the Limits of Zuluness in Colonial Natal. In: Carton B, Laband J, Sithole J, editors. Zulu Identities: Being Zulu, Past and Present. UKZN Press; Durban: 2008. pp. 281–289. [Google Scholar]

- Meekers D. The process of marriage in African societies: a multiple indicator approach. Population and Development Review. 1992;18(1):61–78. doi:10.2307/1971859. [Google Scholar]

- Mkhize N. African traditions and the social, economic and moral dimensions of fatherhood. In: Morrell R, Richter L, editors. Baba: Men and Fatherhood in South Africa. HSRC Press; Cape Town: 2006. pp. 183–198. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery C, Hosegood V, Busza J, Timaeus IM. Men’s involvement in the South African family: Engendering change in the AIDS era. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;62(10):2411–2419. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.026. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore HL. Households and gender in a South African bantustan, a comment. African Studies. 1994;53(1):137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Morrell R. Fathers, fatherhood and masculinity in South Africa. In: Morrell R, Richter L, editors. Baba: Men and Fatherhood in South Africa. HSRC Press; Cape Town: 2006. pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Morrell R, Richter L. Introduction. In: Morrell R, Richter L, editors. Baba: Men and Fatherhood in South Africa. HSRC Press; Cape Town: 2006. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Moultrie TA, Dorrington R. Estimation of fertility from the 2001 South Africa Census data. Centre for Actuarial Research report; Cape Town: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Moultrie TA, Hosegood V, McGrath NM, Hill C, Herbst K, Newell M. Refining the Criteria for Stalled Fertility Declines: An Application to Rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, 1990-2005. Studies in Family Planning. 2008;39(1):39–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00149.x. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moultrie TA, Timæus IM. Fertility and living arrangements in South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies. 2001;27(2):207–223. doi:10.1080/03057070120049930. [Google Scholar]

- Moultrie TA, Timæus IM. The South African fertility decline: evidence from two censuses and a Demographic and Health Survey. Population Studies. 2003;57(3):265–283. doi: 10.1080/0032472032000137808. doi:10.1080/0032472032000137808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C. Migrant labour and changing family structure in the rural periphery of Southern Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies. 1980;6(2):139–156. doi:10.1080/03057078008708011. [Google Scholar]

- Murray C. Families Divided: the Impact of Migration in Lesotho. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Murray C. Class and the developmental cycle: household strategies of survival in the rural periphery of Southern Africa. In: Guyer JI, Peters PE, editors. Conceptualizing the household: issues of theory, method, and application. 1985. pp. 14–21. Unpublished workshop report. [Google Scholar]

- Muthwa SW. Economic Survival Strategies of Female-headed Households: The Case of Soweto, South Africa. School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London; London: 1995. PhD thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Niehaus I. Disharmonious spouses and harmonious siblings: conceptualizing household formation among urban residents of Qwaqwa. African Studies. 1994;53(1):115–136. [Google Scholar]

- Nnko S, Boerma JT, Urassa M, Mwaluko G, Zaba B. Secretive females or swaggering males? An assessment of the quality of sexual partnership reporting in rural Tanzania. Social Science and Medicine. 2004;59(2):299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauw BA. The Second Generation: A Study of the Family among Urbanized Bantu in East London. Oxford University Press; Cape Town: 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Posel D. State, power and gender: conflict over the registration of African customary marriage in South Africa c.1910-1970. Journal of Historical Sociology. 1995;8(3):223–256. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6443.1995.tb00088.x. [Google Scholar]

- Preston-Whyte E. Kinship and marriage. In: Hammond-Tooke W, editor. The Bantu-speaking peoples of southern Africa. Routledge and Kegan Paul; London and Boston: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Preston-Whyte E. Families without marriage: a Zulu case study. In: Argyle J, Preston-Whyte E, editors. Social System and Tradition in Southern Africa. Essays in Honour of Eileen Krige. Oxford University Press; Cape Town: 1978. pp. 55–85. [Google Scholar]

- Preston-Whyte E. Women-headed households and development: the relevance of cross-cultural models for research on black women in southern Africa. Africanus. 1988;18:58–76. [Google Scholar]

- Preston-Whyte E. Women who are not married: fertility, ‘illegitimacy’, and the nature of households and domestic groups among single African women in Durban. South African Journal of Sociology. 1993;24(3):63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Preston-Whyte E, Zondi M. Assessing illegitimacy in South Africa. In: Burman S, Preston-Whyte E, editors. Questionable Issue: Illegitimacy in South Africa. Oxford University Press; Cape Town: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ramphele M. A Bed Called Home: Life in the Migrant Labour Hostels of Cape Town. David Phillip; Cape Town and Johannesburg: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rice BD, Bätzing-Feigenbaum J, Hosegood V, Tanser F, Hill C, Bärnighausen T, Herbst K, Welt T, Newell M. Population and antenatal-based HIV prevalence estimates in a high contracepting female population in rural South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(160) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-160. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. Understanding black households: the problem. Social Dynamics. 2003;29(2):5–47. [Google Scholar]

- South African government . Recognition of Customary Marriages Act, 1998 (Act No 12 of 1998) Regulations, R1101, 1 November 2000. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Speizer IS. A marriage trichotomy and its applications. Demography. 1995;32(4):533–542. doi:10.2307/2061673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel A. Rural differentiation and the diffusion of migrant labour remittances in Lesotho. In: Mayer P, editor. Black villagers in an industrial society. Anthropological perspectives on labour migration in South Africa. Oxford University Press; Cape Town: 1980. pp. 109–168. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel A, Watson V, Wilkinson P. Domestic diversity and fluidity among some African households in Greater Cape Town. Social Dynamics. 1996;22(1):7–30. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa . Marriages and divorce, 1997. Statistical release P0307. Statistics South Africa; Pretoria: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tanser F, Hosegood V, Bärnighausen T, Herbst K, Nyirenda M, Muhwava W, Newell C, Viljoen J, Mutevedzi T, Newell M. Cohort Profile: Africa Centre Demographic Information System (ACDIS) and population-based HIV survey. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;37(5):956–962. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym211. doi:10.1093/ije/dym211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend N, Madhavan S, Garey AI. Father presence in rural South Africa: historical changes and life-course patterns. International Journal of Sociology of the Family. 2006;32(2):173–190. [Google Scholar]

- Udjo E. Marital patterns and fertility in South Africa: the evidence from the 1996 population census; Poster presented in IUSSP XXIV International Population Conference; San Salvadore, Brazil. August 18-24 2001.2001. [Google Scholar]