Summary

Glycosylation is one of the most predominant forms of cell surface protein modifications and yet its de-regulation in cancer and contribution to tumor microenvironment interactions remains poorly understood. In this issue of Cancer Discovery, Reticker-Flynn and Bhatia characterize an enzymatic switch in lung cancer cells that triggers aberrant surface protein glycosylation patterns, adhesion to lectins on the surface of inflammatory cells, and subsequent metastatic colonization of the liver.

In recent years a myriad of cell surface and secreted proteins have been implicated in cancer metastasis. These molecules include growth factors, cytokines, cell surface proteins, and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins. Their aberrant production, either by malignant cells or cells within the surrounding tissue, is essential for multiple steps in the metastatic process. Many of these molecules mediate paracrine and juxtacrine interactions that enable disseminated tumor cells to form macro-metastasis in distant organs. At the same time, less is known about the post-translational modification of these proteins and whether this process can be fine-tuned at the cell surface or in the ECM.

One of the most predominant forms of protein modifications is glycosylation. Cell surface proteins are heavily glycosylated and glycoproteins are a major component of the ECM. Embryonic development and cell transformation are accompanied by changes in overall cellular glycosylation. Glycan changes in tumor cells can take a variety of forms. Early evidence came from the observation that plant lectins can enhance the binding and agglutination of tumor cells. Tumors cells of various origins show overall increases in sialic sugars on membrane glycoproteins and glycolipids (1). Interestingly, progression of the most frequent subtype of lung cancer, lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), has been associated with increased levels of glycosylated protein in patient sera (2). Despite its clinical relevance, the biological and mechanistic implication of this observation is poorly understood.

Retickler-Flynn and colleagues previously developed an elegant approach to quantify the differential adhesion of cancer cells to an array of ECM proteins (3). Using a series of lung cancer cell lines established and selected from a prototypical mouse model of LUAD (4), they discovered that metastatic cells preferentially bind to Galectin-3 (Gal-3) (3). Gal-3 is a family member of carbohydrate-binding lectins whose expression is associated with inflammatory diseases and cancer. Gal-3 can be expressed by tumor cells and enhances their binding to the ECM, while a soluble form of Gal-3 functions as a monocyte chemoattractant. In this issue of Cancer Discovery, (5), the authors describe an inflammatory myeloid population that also constitutively expresses Gal-3 at their cell surface. These Gal-3+ CD11b+ cells are mobilized in the blood of LUAD bearing mice and are detected in the liver soon following subcutaneous tumor transplantation. Various myeloid cell subpopulations are known to be key stromal mediators of tumor progression and are mobilized to tissues to either establish or sustain the maintenance of the so-called metastatic niche(s) (6). In their model, Retickler-Flynn show that the mobilization of Gal-3+ CD11b+ cells is induced by paracrine cytokines (e.g. IL-6) secreted by LUAD cells regardless of their metastatic competence. However, only LUAD cells with high metastatic potential are capable of binding to Gal-3+ CD11b+ cells. Importantly, Gal-3 is directly presented by myeloid cells and is therefore accessible for binding to other glycoproteins through its carbohydrate recognition domain.

Gal-3 exhibits specific affinities for the Thomsen-Friedenreich Antigen (T-antigen or Galβ1-3GalNAcα1-Ser/Thr), a modification typical of many glycoproteins on the surface of tumor cells (7). This interaction occurs through the core 1 disaccharide of T-antigen and further T-antigen glycosylation impairs its binding capacity. Interestingly, the metastatic competence of the murine LUAD lines in this study correlates with the presence of T-antigen across a broad range of cell surface glycoproteins. Elevated presentation of T-antigen by tumor cells is also observed in lymph node metastasis resected from human lung cancer patients. Since several enzymes are involved in the glycosylation of T-antigen, the authors propose that the binding of LUAD cells to Gal-3 requires the activity of specific glycosyltransferases, rather than a change in overall glycoprotein levels. Consistent with this hypothesis, highly metastatic LUAD cells over-express the sialyltransferase St6galnac4 and underexpress the glucosaminyltransferase Gcnt3. Because St6galnac4 and Gcnt3 catalyze disaccharide capping and branching respectively, the net result of this expression pattern is predicted to be increased presentation and binding of T-antigen to Gal-3. Finally, when St6galnac4 in highly metastatic cells is reduced using an shRNA, the ability of these cells to colonize the liver was abated.

While providing exciting new avenues for biochemical and biological research on metastasis, this study raises a number of important questions and challenges. Mechanistically, it is notable that the metastatic LUAD cells used in this study adhere to a combination of ECM proteins that also includes Fibronectin, Laminin and Galectin-8 (3), some of which are glycosylated and may cooperate with Gal-3. Although cell surface glycosylation increases the probability of cell-matrix adhesion, these modifications may also have more critical downstream signaling outputs. The formation of multivalent complexes of soluble galectins with cell surface glycoproteins, such as growth factor receptors, organizes their assembly for signal transduction. Since metastasis ultimately arises from tumor re-initiation in secondary sites, altered cell surface glycosylation may trigger signaling pathways required for the survival and/or outgrowth of disseminated tumor cells.

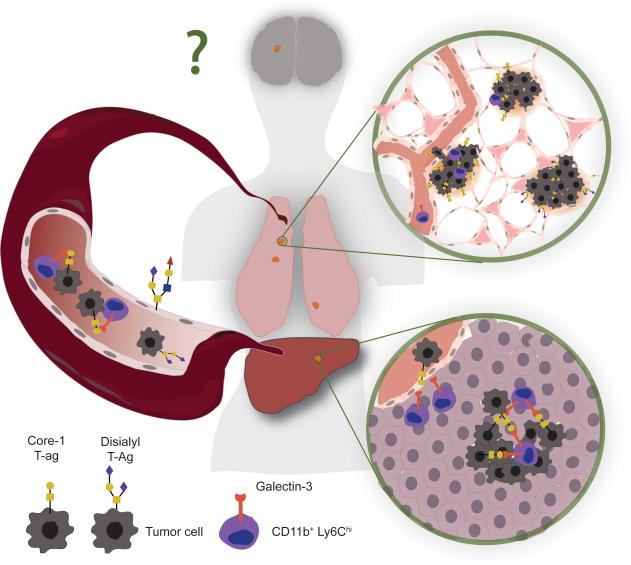

In their genomic analysis of early stage human LUADs, the authors report copy number alterations in GCNT3. If confirmed, this result may suggest that mutations in protein glycosylation pathways could be a feature of particular lung cancer molecular subtypes. Moreover, the recruitment of Gal-3+ stromal cells in primary tumors may also provide broader selective advantages during tumorigenesis (Figure 1). This is particularly relevant given that myeloid cells can regulate the early steps of lung carcinogenesis (8) and are well known to support tumor cell intravasation, survival in circulation, and extravasation in distant organs. It would also be important to ascertain if the glycosyltransferases identified here are required for metastasis to the central nervous system, the most clinically relevant site of relapse in LUAD patients.

Figure 1.

Changes in sialyl glycosylation on the surface of lung adenocarcinoma cells regulates their interaction with inflammatory monocytes. A subpopulation of tumor cells differentially express specific glycosyltransferases to truncate cell surface glycans. Gal-3 expressed at the surface of monocytes preferentially binds to truncated glycans. The Gal-3 mediated interaction between monocytes and tumor cells is observed during liver colonization, but may also occur at different steps of cancer progression to support lung tumor expansion, intravasation, survival in circulation, extravasation, and secondary outgrowth. Analogous glycoprotein modifications may be required for lung cancer metastasis to other relevant organs, such as the brain.

The study by Reticker-Flynn complements a number of recent findings linking the function of sialytransferases and modifications of the O-glycome to metastasis (9, 10). This body of work underscores the complex and potentially antagonistic activity of different glycosyltransferases. Ultimately, the branching pattern and elongation of particular protein glycosyl group may be more predictive of their functional output. Clearly, these biochemical modifications warrant further investigation as modulators of specific tumor microenvironment interactions. Their characterization in other models of lung cancer should clarify the therapeutic window and target specificity required of putative glycosylation inhibitors during the treatment of metastatic disease.

Acknowledgments

Our research is funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute (1R01CA166376, 1R21CA170537, and 1R01CA191489) (to D.X.N.).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Bull C, Stoel MA, den Brok MH, Adema GJ. Sialic acids sweeten a tumor's life. Cancer Res. 2014;74:3199–204. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liang Y, Ma T, Thakur A, Yu H, Gao L, Shi P, et al. Differentially expressed glycosylated patterns of alpha-1-antitrypsin as serum biomarkers for the diagnosis of lung cancer. Glycobiology. 2014 doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwu115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reticker-Flynn NE, Malta DF, Winslow MM, Lamar JM, Xu MJ, Underhill GH, et al. A combinatorial extracellular matrix platform identifies cell-extracellular matrix interactions that correlate with metastasis. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1122. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winslow MM, Dayton TL, Verhaak RG, Kim-Kiselak C, Snyder EL, Feldser DM, et al. Suppression of lung adenocarcinoma progression by Nkx2-1. Nature. 2011;473:101–4. doi: 10.1038/nature09881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reticker-Flynn NE, Bhatia SN. Aberrant glycosylation promotes lung cancer metastasis through adhesion to galectins in the metastatic niche. Cancer Discov. 2015 doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quail DF, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med. 2013;19:1423–37. doi: 10.1038/nm.3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Springer GF. T and Tn, general carcinoma autoantigens. Science. 1984;224:1198–206. doi: 10.1126/science.6729450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zaynagetdinov R, Sherrill TP, Polosukhin VV, Han W, Ausborn JA, McLoed AG, et al. A critical role for macrophages in promotion of urethane-induced lung carcinogenesis. J Immunol. 2011;187:5703–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bos PD, Zhang XH, Nadal C, Shu W, Gomis RR, Nguyen DX, et al. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to the brain. Nature. 2009;459:1005–9. doi: 10.1038/nature08021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murugaesu N, Iravani M, van Weverwijk A, Ivetic A, Johnson DA, Antonopoulos A, et al. An in vivo functional screen identifies ST6GalNAc2 sialyltransferase as a breast cancer metastasis suppressor. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:304–17. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]