Graphical abstract

Keywords: Sugar nucleotide, Modified nucleobase, Enzymatic synthesis, Pyrophosphatase, Epimerase

Highlights

-

•

Enzymatic conversion of 5-aryl-substituted UTP to UDP-galactose derivatives.

-

•

UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase was particularly effective.

-

•

Epimerization of 5-substituted UDP-glucoses with Erwinia UDP-glucose 4″-epimerase.

Abstract

Glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase in conjunction with UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase was found to catalyse the conversion of a range of 5-substituted UTP derivatives into the corresponding UDP-galactose derivatives in poor yield. Notably the 5-iodo derivative was not converted to UDP-sugar. In contrast, UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in conjunction with inorganic pyrophosphatase was particularly effective at converting 5-substituted UTP derivatives, including the iodo compound, into a range of gluco-configured 5-substituted UDP-sugar derivatives in good yields. Attempts to effect 4″-epimerization of these 5-substituted UDP-glucose with UDP-glucose 4″-epimerase from yeast were unsuccessful, while use of the corresponding enzyme from Erwinia amylovora resulted in efficient epimerization of only 5-iodo-UDP-Glc, but not the corresponding 5-aryl derivatives, to give 5-iodo-UDP-Gal. Given the established potential for Pd-mediated cross-coupling of 5-iodo-UDP-sugars, this provides convenient access to the galacto-configured 5-substituted-UDP-sugars from gluco-configured substrates and 5-iodo-UTP.

1. Introduction

Glycosyltransferases (GTs) are a large class of carbohydrate active enzymes that are involved in numerous important biological processes, with impact in cellular adhesion, carcinogenesis and neurobiology, amongst many others.1–3 As such, GTs have enormous potential as targets for drug discovery. For the full realization of this potential, both chemical inhibitors, and operationally simple and generally applicable GT bioassays, especially for high-throughput inhibitor screening, are indispensable tools.4 Many GTs use UDP-sugars as their donor substrates, and non-natural derivatives of these sugar-nucleotides are therefore of considerable interest as GT inhibitor candidates and assay tools.5 Wagner et al. have recently described 5-substituted UDP-sugars (Fig. 1) as a new class of GT inhibitors with a unique mode of action.6–9 Depending on the nature of the 5-substituent, these 5-substituted UDP-sugars also exhibit useful fluorescent properties,10–12 and we have recently reported a series of novel auto-fluorescent derivatives of UDP-sugars with a fluorogenic substituent at position 5 of the uracil base (Fig. 1).10,11 In a proof of concept study, Wagner et al. demonstrated that fluorescence emission by 5-formylthienyl-UDP-α-d-galactose (1f) is quenched upon specific binding to several retaining galactosyltransferases (GalTs), and that this effect can be used as a read-out in ligand-displacement experiments.11 To date, such 5-substituted UDP-sugar probes had to be prepared using chemical synthesis (reviewed in Ref. 5). For instance, Wagner et al. showed that it is possible to directly transform 5-iodo-UDP-α-d-Gal (1b) into 5-formylthienyl-UDP-α-d-Gal (1f) using Suzuki coupling under aqueous conditions.6 The aim of the current work was to explore alternative methods for the preparation of 5-substituted UDP-sugars (1–4) using chemo-enzymatic approaches (reviewed in Ref. 13) starting from 5-substituted UTP derivatives 5b–f.12

Figure 1.

Target nucleobase-modified UDP-sugar derivatives (1)–(4) and UTP precursors (5).

2. Results and discussion

Access to gluco- and galacto-configured UDP-sugars lies at the heart of this study. In brief, enzymatic synthesis approaches to such compounds may employ a number of different enzymes, either affording the required sugar nucleotide via pyrophosphate bond formation [action of uridylyltransferase (GalPUT) or pyrophosphorylase (GalU)], or by epimerization of the C-4″ stereochemistry of the pre-formed sugar nucleotide [action of epimerase (GalE)] (Scheme 1).13 We have employed both the former and latter approaches in syntheses of natural14 and non-natural14–17 sugar nucleotides.

Scheme 1.

Strategies for enzymatic preparation of based-modified UDP-Glucose and UDP-Galactose. X is as outlined in Figure 1; GalPUT = galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase; GalU = UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase; GalE = UDP-Galactose 4″-epimerase; IPP = inorganic pyrophosphatase. Arrows in black indicate a one pot reaction; arrows in grey indicate a separate reaction.

2.1. Enzymatic synthesis of 5-substituted UDP-Gal derivatives using a GalU-GalPUT protocol

2.1.1. One-pot GalU-GalPUT reactions

In an attempt to generate 5-substituted UDP-Gal derivatives 1b–f, a multienzyme approach was assessed (Scheme 1).14,15 This protocol employs UTP (5a) and glucose-1-phosphate with UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (GalU, EC 2.7.7.9) to generate UDP-Glc (2a) in situ. Galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase (GalPUT, EC 2.7.7.12) then catalyses the reaction of UDP-Glc (2a) and α-d-galactose-1-phosphate, giving the corresponding UDP-Gal (1a). UDP-Glc (2a) is only produced in catalytic quantity (typically 0.5 mol % related to sugar-1-phosphate) as it is continuously recycled, via Glc-1-P, by the action of GalU (Scheme 1). In this reaction, inorganic pyrophosphate is released and inorganic pyrophosphatase (IPP) is employed to achieve its hydrolysis, driving the overall equilibrium of the multi-enzyme reaction towards the formation of the desired UDP-Gal (1a) sugar nucleotide.

In a control experiment, Gal-1-P was converted into UDP-Gal (1a) using an equimolar quantity of UTP (5a) and a catalytic amount of UDP-Glc (2a). The transformation reached a complete conversion (by SAX HPLC) within 1 h (data not shown). Next, the 5-substituted UTP derivatives 5b–f were used in combination with Gal-1-P in an attempt to generate the corresponding 5-substituted UDP-Gal derivatives 1b–f (Fig. 1; Scheme 1). In all cases, reaction with the 5-substituted UTPs was slower than with the parent compound. After 24 h incubation, formation of product was detected in the case of 5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-UDP-Gal (1d) (5%) and 5-(2-furyl)-UDP-Gal (1e) (23%) and the products were isolated and characterized. The formation of 5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-UDP-Glc (2d) and 5-(2-furyl)-UDP-Glc (2e) as intermediates in the reaction is implicit, but their presence in the reaction mixture was not detected. The 5-iodo-UTP (5b) and the 5-(5-formyl-2-thienyl)-UTP (5f) derivatives were not converted into the corresponding sugar nucleotides at all; in the case of the 5-phenyl-UTP (5c), the conversion was less than 5% and the product 1c was not isolable. In order to assess which of the enzymes, GalU or GalPUT, is failing to use these latter base-modified compounds as substrates, a series of reverse reactions and inhibition experiments was performed.

2.1.2. The GalPUT reaction in reverse

In the presence of excess Glc-1-P, GalPUT can be used to run the reverse conversion, UDP-Gal (1a) into UDP-Glc (2a). As shown in Figure 2A, after 1 h the conversion of substrate into product is nearly complete, as judged by 1H NMR analysis of the diagnostic anomeric signals (dd) of the sugar phosphates. When a synthetic sample of 5-(5-formyl-2-thienyl)-UDP-Gal (1f) was subjected to equivalent conditions, no conversion was observed after 1 h (data not shown). After extended incubation (24 h) only traces of 5-(5-formyl-2-thienyl)-UDP-Glc (2f) and Gal-1-P were detectable by 1H NMR (Fig. 2B). This result suggests that 5-(5-formyl-2-thienyl)-UDP-Gal (1f) either does not bind to the GalPUT active site or that it might bind in a non-productive way. If the latter were true, 1f should act as a GalPUT inhibitor.

Figure 2.

Reverse action of GalPUT. (A) Incubation of UDP-Gal (1a) and Glc-1-P. (B): Incubation of 5-(5-formyl-2-thienyl)-UDP-Gal (1f) and Glc-1-P.

2.1.3. 5-(5-Formyl-2-thienyl)-UDP-Gal as a GalPUT inhibitor

When UDP-Gal (1a), Glc-1-P and 1f were mixed in a molar ratio 1:10:3.5, the conversion to UDP-Glc (2a) after 30 min was the same as in the absence of 1f (not shown), implying that 1f does not compete with UDP-Gal (1a) to bind in the active site of GalPUT. This implies that the formylthienyl substitution of the uracil base prevents the corresponding sugar nucleotides from binding to GalPUT and explains the observed lack of conversion of 2f into 1f in the one-pot GalU-GalPUT protocol. However, the lack of conversion might also be due to a lack of tolerance of GalU for 5-substitution of the uracil ring of UTP.

2.1.4. Competing 5-substituted-UTP and unsubstituted UTP as GalU substrates

A series of experiments were conducted to assess the flexibility of GalU towards 5-substitution of its UTP substrate. A control experiment [GalU, Glc-1-P, UTP (5a)] showed the rapid conversion of UTP (5a) into UDP-Glc (2a), as indicated by the diagnostic uracil H6 signals in 1H NMR spectra (Fig. 3A). In a competition experiment employing Glc-1-P, UTP (5a) and 5-iodo-UTP (5b) in molar ratio 1:1:5, UTP (5a) remained almost completely intact (Fig. 3B). Instead, 5-iodo-UTP (5b) was rapidly converted into 5-iodo-UDP-Glc (2b), as shown by a new H6 signal (Fig. 3B) and confirmed by LC–MS: a molecular ion for 5-iodo-UDP-Glc (2b) ([M−H]− m/z 691) was detected, but one for UDP-Glc (2a) ([M−H]− m/z 565) was absent. These data suggest that, if used in excess, 5-iodo-UTP (5b) can out-compete UTP (5a), the natural substrate of GalU, indicating some degree of relaxed GalU substrate specificity. The fact that no formation of 5-iodo-UDP-Gal (1b) was observed in the multi-enzyme transformation (Scheme 1) suggests that although a small quantity of 5-iodo-UDP-Glc (2b) may have been formed in that reaction, it could not be further processed by GalPUT.

Figure 3.

UTP (5a) and 5I-UTP (5b) competition in GalU mediated conversion of Glc-1-P into the corresponding sugar nucleotides. (A) control with UTP (5a) only. (B) UTP (5a) and large excess 5I-UTP (5b).

2.2. Enzymatic synthesis of 5-substituted UDP-Glc 2b–f using GalU

2.2.1. GalU reactions with substituted UTPs

The results presented above indicate that GalU possesses a degree of substrate flexibility regarding 5-substitution of UTP, potentially offering easy access to 5-substituted UDP-Glc (2b–f) derivatives. This was indeed the case when 5-substituted UTP derivatives 5b–f and an equimolar amount of Glc-1-P were subjected to GalU (Fig. 4). Conversions to the corresponding sugar nucleotides 2b–f ranged from 9% to 54% after 120 min. Unsurprisingly, the lowest conversion was detected for the bulky 5-(5-formyl-2-thienyl)-derivative 2f. A control reaction of UTP (5a) with Glc-1-P under the same conditions gave 57% conversion to UDP-Glc (2a). When inorganic pyrophosphatase (IPP) was added to reactions, the conversions could be further improved (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

GalU-mediated formation of 5-substituted UDP-Glc derivatives in the absence of IPP (time point 120 min). X indicates: a = H, b = I, c = Ph, d = 4-MeO-Ph, e = 2-furyl, f = 5-formyl-2-thienyl.

Under these conditions, the conversion of 5f into the 5-(5-formyl-2-thienyl)-derivative 2f was a tolerable 21%. GalU also showed remarkable substrate flexibility towards the configuration of sugar-1-phosphates18—a feature that it has in common with other pyrophosphatases, such as RmlA.19,20 When UTP (5a) was employed as a co-substrate, GalU proved capable of accepting α-d-glucosamine-1-phosphate (GlcN-1-P) and N-acetyl-α-d-glucosamine-1-phosphate (GlcNAc-1-P), as well as α-d-galactose-1-phosphate (Gal-1-P) (Fig. 5). Conversions to the corresponding UDP-sugars 1a, 3a and 4a, respectively, reached 39–48% after 120 min (Fig. 5). With 5-iodo-UTP (5b) the GalU-mediated conversions were lower in the case of GlcN-1-P (42%) and GlcNAc-1-P (20%); disconcertingly, no conversion at all was detected in the case of Gal-1-P (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

GalU mediated transformations of UTP (5a) and 5I-UTP (5b) with three different sugar-1-phosphates (Gal-1-P, GlcN-1-P or GlcNAc-1-P) to the corresponding sugar nucleotides 1, 3 and 4 at time point 120 min.

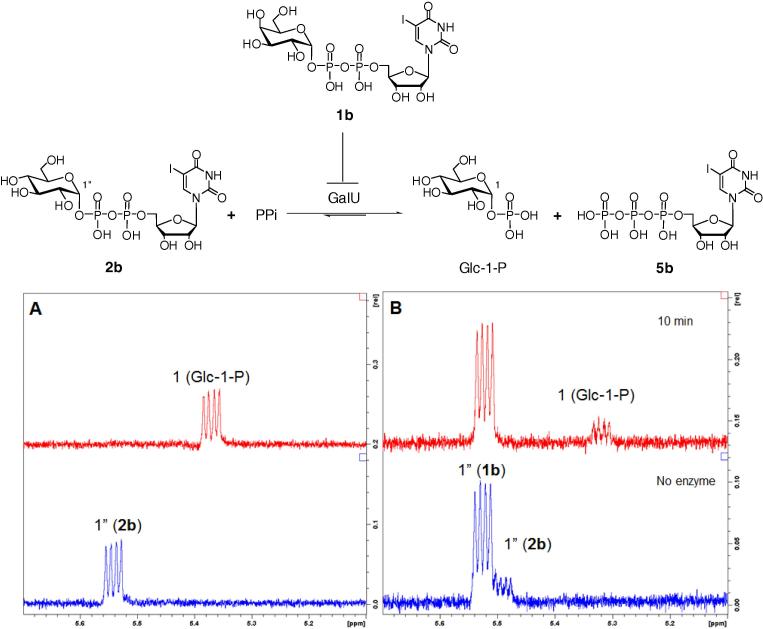

2.2.2. The mutual incompatibility of 5-iodo-UTP and Gal-1-P as co-substrates for GalU

The lack of GalU-mediated conversion of Gal-1-P with 5-iodo-UTP was somewhat unexpected and warranted further analysis. First, it was shown that in the presence of a high concentration of inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi), GalU can perform the reverse conversion from 5-iodo-UDP-Glc (2b) to Glc-1-P and 5-iodo-UTP (5b). The conversion was complete, as judged by 1H NMR [anomeric proton resonances (dd) were used as diagnostic peaks], within 10 min with 10 mM PPi (Fig. 6). When 5-iodo-UDP-Gal (1b) was subjected to analogous conditions no conversion was observed even after incubation for 60 min (data not shown). To see whether the lack of conversion of the galacto-configured substrates was down to lack of binding or to non-productive binding of the substrates, inhibition experiments employing 5 equiv of 5-iodo-UDP-Gal (1b), 1 equiv of 5-iodo-UDP-Glc (2b) and excess PPi were conducted. By 1H NMR, 5-iodo-UDP-Glc (2b) was fully converted into Glc-1-P and 5-iodo-UTP (5b) within 10 min as in the no inhibitor control reaction (Fig. 6). No conversion 5-iodo-UDP-Gal (1b) was detected, which suggests that 5-iodo-UDP-Gal (1b) does not bind to the active site of GalU. A competition experiment was designed to show whether a large excess of Gal-1-P (5 equiv) can outcompete the natural acceptor Glc-1-P (1 equiv) in a GalU mediated conversion of 5-iodo-UTP (5b) (1 equiv) into 5-iodo-UDP-sugar. 1H NMR spectra showed that only 5-iodo-UDP-Glc (2b) was formed and no trace of 5-iodo-UDP-Gal (1b) was detected, even after 120 min (not shown).

Figure 6.

Reverse action of GalU in the presence of excess 10 mM PPi. (A) Conversion of 5-iodo-UDP-Glc (2b) into Glc-1-P. (B) The same as A, but in the presence of excess (5 equiv) 5-iodo-UDP-Gal (1b).

From the above data, it is evident that GalU is not able to simultaneously bind both Gal-1-P and 5-iodo-UTP (5b), although both in their own right are productive substrates in the presence of alternative co-substrates. It may be that a conformational change is required in order to enable co-substrates to bind to GalU in a productive manner, but this is either too slow, or it does not happen at all, when Gal-1-P and 5-iodo-UTP are employed. Further structural analyses are required in order to address this point.

2.3. Enzymatic epimerization of 5-iodo-UDP-Glc (2b) to give the corresponding 5-iodo-UDP-Gal (1b) using GalE

As noted above, GalU successfully produces a range of base-modified gluco-configured UDP-sugars but fails to produce the corresponding galacto-configured compound. The one-pot, GalU-GalPUT protocol showed some flexibility, producing galacto-configured analogues 1d and 1e in low yield, but 1b, 1c and 1f were not accessible by this route. An alternative approach to the galacto-configured series is an epimerization of 4″-OH in the base-modified UDP-Glc derivatives. Uridine-5′-diphosphogalactose 4″-epimerase (GalE, E.C. 5.1.3.2) is an enzyme known to catalyse the conversion of UDP-Gal (1a) into UDP-Glc (2a), with the equilibrium favouring the latter over the former (ca 1:4).21 Previous work suggested that 5-formylthienyl-UDP-Gal (1f) is not a substrate for Streptococcus thermophilus GalE.22 Therefore GalE from two further organisms was assessed: galactose-adapted yeast (ScGalE)23 and Erwinia amylovora (EaGalE).24

As control experiments, the conversion of UDP-Gal (1a) into UDP-Glc (2a) was achieved using both ScGalE and EaGalE and the progress of the epimerization was followed by 1H NMR. Under the condition employed, the equilibrium reaction mixtures were reached within 10 min and the ratio between galacto-/gluco-configured products were approximately 1:4, as expected (Fig. 7). Treatment of 5-formylthienyl-UDP-Gal (1f) with ScGalE and EaGalE did not show any 4″-OH epimerization by 1H NMR, even after prolonged incubation (120 min). Similarly, when 5-iodo-UDP-Gal (1b) was used as a substrate, ScGalE failed to effect conversion, even after extended incubation (120 min).

Figure 7.

EaGalE mediated epimerization. (A) UDP-Gal (1a) into UDP-Glc (2a) (30 min). (B) 5-Iodo-UDP-Glc (2b) into 5-iodo-UDP-Gal (1b) (30 min).

However, in contrast, EaGalE showed rapid epimerization of 5-iodo-UDP-Gal (1b) into 5-iodo-UDP-Glc (2b) and the transformation reached equilibrium after about 30 min giving mixed galacto-/gluco-configured products in the ratio 3:7. The reverse conversion of 2b into 1b using EaGalE was also shown to achieve a ca 7.5:2.5 equilibrium mixture of gluco-/galacto-configured sugar nucleotides after 30 min (Fig. 7).

3. Conclusions

5-Substituted gluco- and galacto-configured UDP-sugars are versatile tools for glycoscience research. To date, access to such compounds has relied on chemical synthesis approaches. Here we have investigated enzymatic synthesis routes to such compounds, relying either on pyrophosphate bond formation [action of uridylyltransferase (GalPUT) or pyrophosphorylase (GalU)] or epimerization of the C-4″ stereochemistry of the pre-formed sugar nucleotide [action of epimerase (GalE)]. These studies demonstrate that the one-pot combination of glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase (GalPUT) and UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (GalU) is able to catalyse the conversion of 5-substituted UTP derivatives into the corresponding 5-substituted UDP-galactose derivatives in a number of instances, albeit in poor yield (<5–23% isolated yield). It appears that the specificity of GalPUT is a limiting factor in the utility of this reaction. In contrast, GalU in conjunction with inorganic pyrophosphatase was able to convert 5-substituted UTP derivatives plus a range of gluco-configured sugar-1-phosphates into the corresponding sugar nucleotides in practical yields (20–98%). Subsequent attempts to convert these gluco-configured compounds to the corresponding galacto-isomers proved problematic, with UDP-glucose 4″-epimerase (GalE) from both yeast and Erwinia proving ineffective for bulky 5-aryl derivatives. However, in contrast to the yeast enzyme, the Erwinia GalE proved effective with 5-iodo-UDP-glucose, readily converting it to 5-iodo-UDP-galactose. Given the established potential for Pd-mediated cross-coupling of 5-iodo-UDP-sugars, the enzymatic procedures elaborated in this study provide useful additions to the repertoire of transformation available for the production of novel sugar nucleotides.

4. Experimental

4.1. General methods

4.1.1. Chemicals

All chemicals and reagents were obtained commercially and used as received unless stated otherwise. The identity of products from our control experiments (1a, 2a and 4a) was confirmed by comparison of 1H NMR spectra and/or HPLC retention times of authentic samples. 5-Substituted UTP derivatives 5b–f12 and 5-iodo-UDP-Gal (1b), 5-iodo-UDP-Glc (2b) and 5-(5-formyl-2-thienyl)-UDP-Gal (1f)7 were prepared by chemical synthesis following published procedures. The identity of the following known compounds were confirmed by comparison of analytical data with published literature: (1b),7 (1d),7 (1e),7 (2b),10 (2c),10 (2d),10 (2e),10 (3a),25 (4b).6

4.1.2. Spectroscopy

1H NMR spectra were recorded in D2O on a Bruker Avance III spectrometer at 400 MHz and chemical shifts are reported with respect to residual HDO at δH 4.70 ppm. High resolution accurate mass spectra were obtained using a Synapt G2 Q-Tof mass spectrometer using negative electrospray ionization. Low resolution mass spectra were obtained using either a Synapt G2 Q-Tof or a DecaXPplus ion trap in ESI negative mode by automated direct injection.

4.1.3. Enzymes

Galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase (GalPUT, EC 2.7.7.12) from Escherichia coli was over-expressed and purified as described earlier.14 Glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase (GalU) from Escherichia coli was over-expressed and purified as described earlier.26 Inorganic pyrophosphatase (IPP) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. Uridine-5′-diphosphogalactose 4″-epimerase (GalE) from galactose-adapted yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae, ScGalE) was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. Uridine-5′-diphosphogalactose 4″-epimerase (GalE) from Erwinia amylovora (EaGalE) was cloned, overexpressed and purified as detailed below.

4.1.4. Erwinia amylovora (EaGalE)

The GalE gene (ENA accession number FN666575.1) was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA isolated from E. amylovora strain Ea273 (ATCC 49946) using the following primers: GalE-F 5′-CGATCACCATGGCTATTTTAGTCACGGGGG and GalE-R 5′-CGATCACTCGAGTCAACTATAGCCTTGGGG. These primers included NcoI and XhoI restriction sites, respectively (underlined). The PCR product was purified from agarose gel using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Germany) and treated for 3 h at 37 °C with NcoI and XhoI (NEB, USA) for double digestion. After purification using QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Germany), the digested PCR product was ligated into pETM-30 vector.27 The construct was propagated in Escherichia coli NovaBlue cells (EMD4Biosciences, Germany), purified using a DNA miniprep kit (Sigma, USA) and sequenced by Microsynth AG (Switzerland) to test the correctness of the gene sequence. E. coli BL21 (DE3) chemically competent cells (EMD4Biosciences, Germany) were transformed with the pETM-30::GalE construct for expression of the recombinant GST-fusion protein. Cells containing the construct were grown overnight in 10 mL 2 × YT medium containing Kanamycin (30 μg mL−1) at 37 °C. The starter culture was used to seed 1 L of medium (1:100 dilution) and the culture was grown at 37 °C for 3 h (O.D. 0.8). The temperature was then decreased to 18 °C and the culture was left to equilibrate for 1 h before induction with 1 mM IPTG for 16 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4500g for 15 min at 4 °C, re-suspended in 50 mL ice cold PBS containing 0.2 mg mL−1 lysozyme and protease inhibitors, stirred for 30 min at room temperature and lysed by sonication (Soniprep, MSE, UK) on ice for 2 min using 2 s cycles (15.6 MHz). After centrifugation at 18000g for 20 min at 4 °C the supernatant was filtered and loaded onto a GSTrap HP 5 mL column (GE Healthcare, Sweden) equilibrated with PBS at a flow rate of 1.5 mL min−1. The column was then washed with PBS until the A280 reached the baseline and the enzyme was eluted with 10 mM reduced glutathione in 50 mM TRIS–HCl buffer at pH 8.0. The eluted protein was dialysed against 50 mM TRIS–HCl buffer at pH 8.0 containing 10% glycerol, concentrated to 0.1 mg mL−1 and stored at −20 °C. Protein purity was confirmed by SDS–PAGE.

4.2. Sugar nucleotide purification methods

4.2.1. Purification method 1

Strong anion-exchange (SAX) HPLC on Poros HQ 50. An aqueous solution of a sample was applied on a Poros HQ 50 column (L/D 50/10 mm, CV = 3.9 mL). The column was first equilibrated with 5 CV of 5 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer, followed by a linear gradient of ammonium bicarbonate from 5 mM to 250 mM in 15 CV, then hold for 5 CV, and finally back to 5 mM ammonium bicarbonate in 3 CV at a flow rate of 8 mL/min and detection with an on-line detector to monitor A265. After multiple injections, the column was washed with 3 CV of 1 M ammonium bicarbonate followed by 3 CV of MQ water.

4.2.2. Purification method 2

Reverse phase (RP) C18 purification. The purification was performed on a Dionex Ultimate 3000 instrument equipped with UV/vis detector. A solution of a sample in water was applied on a Phenomenex Luna 5 μm C18(2) column (L/D 250/10 mm, CV = 19.6 mL) and eluted isocratically with 50 mM Et3NHOAc, pH 6.8 with 1.5% CH3CN in 8 CV at a flow rate of 5 mL/min and detection with on-line UV detector to monitor A265. Fractions containing the sugar nucleotide were pooled and freeze-dried.

4.3. Enzymatic transformations

4.3.1. General procedure 1 (GalU-GalPUT-IPP)

UTP analogue (5a–f, 0.5 mg, 1 equiv), α-d-galactose-1-phosphate (1 equiv) and UDP-Glc (2a, 0.5 mol-%) were dissolved in buffer (500 μL, 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2). A small sample (50 μL) was separated for no enzyme control. Then enzymes were added to give final concentration of GalU (137 μg/mL), IPP (1.4 U/mL) and GalPut (329 μg/mL) in a final volume of 700 μL. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C with gentle shaking. At time points analytical samples were separated (50 μL) and MeOH was added (50 μL) to precipitate the enzymes. The sample was vortexed for 1 min, centrifuged (10,000 rpm for 5 min) and the supernatant was filtered through a disc filter (0.45 μm). The filtrate was analysed by SAX HPLC (10 μL injection, Purification method 1). After 24 h the reaction was quenched by addition of MeOH (the same volume as the sample volume) and processed as indicated for the analytical sample. Products were isolated using SAX HLC (Purification method 1). Pooled fractions containing the sugar nucleotide were freeze-dried. When necessary, Purification method 2 was also applied.

4.3.2. General procedure 2 (GalU)

UTP analogue (5a–f, 0.5 mg, 1 equiv) and sugar-1-phosphate (1 equiv) were dissolved in deuterated buffer (660 μL, 50 mM HEPES pD 8.0, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2) and 1H NMR was acquired (100 scans) of the no enzyme control. GalU (40 μL, final c = 0.14 mg/mL) was added to total 0.7 mL. Where indicated IPP (10 μL, final c = 1.4 U/mL) was added to this mixture. 1H NMR spectra were acquired at time points 10, 30, 60, 120 min to monitor reaction progress. The reaction was quenched by addition of an equal volume of methanol (0.7 mL), and the resulting solution was filtered through a 0.22 μm disc filter and products were purified using Purification method 1.

4.3.3. General procedure 3 (GalE)

Appropriate sugar nucleotide (1a, 1b, 1f, or 2b, 0.5 mg) was dissolved in deuterated buffer (660 μL, 50 mM HEPES pD 8.0, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2) and 1H NMR of no enzyme control was acquired (100 scans). GalE was added (40 μL, final c = 36.6 μg/mL for EaGalE, 140 μg/mL for ScGalE) to give final volume of 0.7 mL and 1H NMR spectra were acquired at time points 10, 30 and 60 min.

4.3.3.1. 5-(5-Formyl-2-thienyl)-UDP-α-d-glucose (2f)

The title compound 2f was prepared from 5-(5-formyl-2-thienyl)-UTP (5f, 0.5 mg, 0.56 μmol) and Glc-1-P (0.17 mg, 0.56 μmol) as described in General procedure 2 and the product was isolated using Purification method 1 followed by Purification method 2 with the following modification: isocratic elution for 20 min at flow 5 mL/min with 50 mM Et3N.HOAc, pH 6.8 with 1.5% (93%, solvent A) and acetonitrile (7%, solvent B), UV detection at 350 and 265 nm. The title compound 2f eluted at Rf = 9.5 min and was obtained after freeze-drying as bistriethylammonium salt (∼0.01 mg, 1.7 %).The diagnostic peaks were extracted from a spectrum of the crude mixture purified by SAX only (Purification method 1) giving bisammonium salt of 2f. 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ 9.69 (1H, s, CHO), 8.32 (1H, s, H-6), 7.92 (1H, d, 3JTh3,Th4 = 4.2 Hz, Th), 7.64 (1H, d, 3JTh3,Th4 = 4.3 Hz, Th), 6.01 (1H, d, 3J1′,2′ = 4.7 Hz, H-1′), 5.51 (1H, dd, 3J1″,2″ = 3.4 Hz, 3J1″,Pβ = 7.3 Hz, H-1″). HRMS, ESI negative: m/z calcd for C20H25N2O18P2S− [M−H]−: 675.0304, found: 675.0304.

4.3.3.2. 5-Iodo-UDP-α-d-glucosamine (3b)

The title compound 3b was prepared from 5-iodo-UTP (5b, 0.5 mg, 0.56 μmol) and GlcN-1-P (0.15 mg, 0.56 μmol) as described in General procedure 2 and the product was isolated using Purification method 1 followed by Purification method 2. The title compound 3b eluted at Rf = 12.9 min and was obtained after freeze-drying as a triethylammonium salt (3b × 0.5 Et3N, 0.1 mg, 20 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ 8.13 (1H, s, H-6), 5.85 (1H, d, 3J1′,2′ = 3.7 Hz, H-1′), 5.66–5.60 (1H, m, H-1″), 4.31–4.27 (2H, m, H-2′, H-3′), 4.21–4.12 (3H, m, H-5a′, H-5b′, H-4′), 3.87–3.66 (5H, m, H-2″, H-3″, H-5″, H-6a″, H-6b″), 3.45–3.39 (1H, m, H-4″), 3.19 (3H, q, 3JCH2,CH3 = 6.8 Hz, (CH3CH2)3N), 1.17 (4.5H, t, 3JCH2,CH3 = 6.8 Hz, (CH3CH2)3N). HRMS, ESI negative: m/z calcd for C15H23IN3O16P2− [M−H]−: 689.9604, found: 689.9596.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the UK BBSRC Institute Strategic Programme Grant on Understanding and Exploiting Metabolism (MET) [BB/J004561/1] and the John Innes Foundation, with additional support by the EPSRC (First Grant EP/D059186/1, to G.K.W.) and the MRC (Grant No. 0901746, to G.K.W.). We thank Dr. M. Malnoy for providing E. amylovora genomic DNA. Plasmid pETM-30 was obtained from the European Molecular Biology Laboratory under a signed Material Transfer Agreement. Part of this work (cloning, overexpression and purification of EaGalE) was supported by the Autonomous Province of Bolzano grant: ‘A structural genomics approach for the study of the virulence and pathogenesis of Erwinia amylovora’ and the Free University of Bolzano grant: Galactose and glucuronic acid metabolism in Erwinia spp. (GAMEs).

Contributor Information

Stefano Benini, Email: stefano.benini@unibz.it.

Gerd K. Wagner, Email: gerd.wagner@kcl.ac.uk.

Robert A. Field, Email: rob.field@jic.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Marth J.D., Grewal P.K. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:874–887. doi: 10.1038/nri2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dube D.H., Bertozzi C.R. Nat. Rev. Drug Disc. 2005;4:477–488. doi: 10.1038/nrd1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rexach J.E., Clark P.M., Hsieh-Wilson L.C. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:97–106. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagner G.K., Pesnot T. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:1939–1949. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner G.K., Pesnot T., Field R.A. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009;26:1172–1194. doi: 10.1039/b909621n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tedaldi L.M., Pierce M., Wagner G.K. Carbohydr. Res. 2012;364:22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Descroix K., Pesnot T., Yoshimura Y., Gehrke S.S., Wakarchuk W., Palcic M.M., Wagner G.K. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:2015–2024. doi: 10.1021/jm201154p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pesnot T., Jorgensen R., Palcic M.M., Wagner G.K. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6:321–323. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jorgensen R., Pesnot T., Lee H.J., Palcic M.M., Wagner G.K. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:26201–26208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.465963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pesnot T., Wagner G.K. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:2884–2891. doi: 10.1039/b805216f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pesnot T., Palcic M.M., Wagner G.K. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:1392–1398. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pesnot T., Tedaldi L.M., Jambrina P.G., Rosta E., Wagner G.K. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013;11:6357–6371. doi: 10.1039/c3ob40485d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thibodeaux C.J., Melancon C.E., Liu H.W. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:9814–9859. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Errey J.C., Mukhopadhyay B., Kartha K.P.R., Field R.A. Chem. Commun. 2004:2706–2707. doi: 10.1039/b410184g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Errey J.C., Mann M.C., Fairhurst S.A., Hill L., McNeil M.R., Naismith J.H., Percy J.M., Whitfield C., Field R.A. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009;7:1009–1016. doi: 10.1039/b815549f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang M., Proctor M.R., Bolam D.N., Errey J.C., Field R.A., Gilbert H.J., Davis B.G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:9336–9337. doi: 10.1021/ja051482n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caputi L., Rejzek M., Louveau T., O’Neill E.C., Hill L., Osbourn A., Field R.A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:4762–4767. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.05.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schomburg D., Stephan D. In: Enzyme Handbook. Schomburg D., Stephan D., editors. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg: 1997. pp. 517–525. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moretti R., Thorson J.S. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:16942–16947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Timmons S.C., Hui J.P.M., Pearson J.L., Peltier P., Daniellou R., Nugier-Chauvin C., Soo E.C., Syvitski R.T., Ferrieres V., Jakeman D.L. Org. Lett. 2008;10:161–163. doi: 10.1021/ol7023949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holden H.M., Rayment I., Thoden J.B. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:43885–43888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R300025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Descroix K., Wagner G.K. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011;9:1855–1863. doi: 10.1039/c0ob00630k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maxwell E.S., de Robichon-Szulmajster H. J. Biol. Chem. 1960;235:308–312. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Metzger M., Bellemann P., Bugert P., Geider K. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:450–459. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.2.450-459.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morais L.L., Yuasa H., Bennis K., Ripoche I., Auzanneau F.I. Can. J. Chem. 2006;84:587–596. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Z.Y., Zhang J.B., Chen X., Wang P.G. ChemBioChem. 2002;3:348–355. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020402)3:4<348::AID-CBIC348>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dummler A., Lawrence A.M., de Marco A. Microb. Cell Fact. 2005;4:34. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-4-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]