Abstract

High-throughput screening (HTS) has been integrated into the drug discovery process, and multiple assay formats have been widely used in many different disease areas but with limited focus on infectious agents. In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of HTS campaigns using infectious wild-type pathogens rather than surrogates or biochemical pathogen-derived targets. Concurrently, enhanced emerging pathogen surveillance and increased human mobility have resulted in an increase in the emergence and dissemination of infectious human pathogens with serious public health, economic, and social implications at global levels. Adapting the HTS drug discovery process to biocontainment laboratories to develop new drugs for these previously uncharacterized and highly pathogenic agents is now feasible, but HTS at higher biosafety levels (BSL) presents a number of unique challenges. HTS has been conducted with multiple bacterial and viral pathogens at both BSL-2 and BSL-3, and pilot screens have recently been extended to BSL-4 environments for both Nipah and Ebola viruses. These recent successful efforts demonstrate that HTS can be safely conducted at the highest levels of biological containment. This review outlines the specific issues that must be considered in the execution of an HTS drug discovery program for high-containment pathogens. We present an overview of the requirements for HTS in high-level biocontainment laboratories.

Introduction

High-throughput screening (HTS) is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery and is now widely used in both the pharmaceutical and academic fields.1 When HTS processes are used for screening against infectious pathogens, modern biosafety requires the adaptation of HTS operations to a biosafety-level (BSL) laboratory, which is a biocontained environment appropriate for the specific pathogen.2,3 Biosafety and regulatory requirements for pathogen research have a tremendous impact on the design and execution of HTS campaigns with infectious agents. In this study, we describe modifications to the standard HTS process that have allowed us to identify potential therapeutic candidates against BSL-3 and -4 pathogens.

Four laboratory biosafety levels (BSL-1 through -4) for activities involving infectious microorganisms and laboratory animals have been specified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).4 Table 1 designates the levels, in order, by degree of protection. Additional degrees of protection are conferred as the BSL increases. These levels of protection are cumulative and are provided to the personnel, environment, and community for the enhancement of worker safety, environmental protection, and to address the perceived and actual risks when working with pathogenic agents requiring increasing levels of containment. Activities involving infectious pathogens require standard microbiological practices that are common to all laboratories and have evolved over time. They now may be performed in facilities that exceed BSL-1 biocontainment, with an agent-specific minimum of BSL-2, -3, or -4 for safety and regulatory compliance. The evolution of an HTS facility for discovery of therapeutics against infectious pathogens has occurred over the past decade, largely as a result of miniaturization of automated robots, the commercial availability of custom biological safety cabinets (BSCs) specifically designed to contain HTS equipment, and the construction of new, government program-sponsored high-biocontainment laboratories. HTS has traditionally been performed at the BSL-1 because the large footprint of the automated equipment prevented their inclusion inside BSCs. When BSCs were used, it was more to preserve the sterility of the cultured cells used in assays than to contain infectious pathogens or protect operators. HTS in high-biocontainment laboratories requires the inclusion of important logistical and operational factors and the adherence to additional regulatory oversight and requirements (as delineated in the Select Agent Rule, CDC Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories [BMBL] and USDA Guidelines).2,4

Table 1.

Biosafety Level Requirements for High-Throughput Screen Laboratories

| Biosafety level | Pathogen characteristics | Required microbiological safety practices | Engineering controls and PPE | Special considerations for HTS operations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Not known to cause disease in healthy adults, for example, Baculovirus, DH5 alpha Escherichia coli | Standard | No primary barriers required PPE: laboratory coats and gloves; eye, face protections, as needed |

None |

| 2 | Cause human disease Transmission through percutaneous injury, ingestion, mucous membranes, inhalation For example, influenza, dengue, cholera, salmonella |

BSL-1 plus: Limited access Biohazard warning signs Sharps precautions Biosafety manual defining any needed waste decontamination or medical surveillance practices |

Primary barriers: BSCs or other physical containment devices used for all manipulations that cause splashes or aerosols of infectious materials PPE: Laboratory coats, gloves, face and eye protection, as needed |

Aerosol generation Equipment footprint size for BSC inclusion Equipment decontamination for maintenance by a qualified technician |

| 3 | Indigenous or exotic agents that may cause serious or potentially lethal disease through inhalation, percutaneous injury, ingestion, mucous membranes For example, West Nile virus, rabies, tuberculosis, Bacillus anthracis |

BSL-2 plus: Controlled access Decontamination of all waste Decontamination of laboratory clothing before laundering |

Primary barriers: BSCs or other physical containment devices used for all open manipulations of pathogens PPE: Protective laboratory clothing, gloves, face, eye, and respiratory protection, as needed. Varies with pathogen |

PPE movement restrictions Operator time in laboratory restrictions Space restrictions Equipment decontamination by VHP or formaldehyde for facility removal Facility entry for qualified maintenance technicians is possible |

| 3+ | Required for work with highly pathogenic agents (human or livestock) | BSL-3 plus: Clothing change before entering |

Primary barriers: PPE: PAPR |

|

| 3-Ag | For example, highly pathogenic avian influenza, Rift Valley fever virus | Shower before exit | ||

| 4 | Dangerous/exotic, high-mortality agents with a high risk of aerosol transmission for which there are no vaccines or therapeutics Agents with a close or identical antigenic relationship to an agent requiring BSL-4 Related agents with unknown risk of transmission For example, Nipah, Lassa, Ebola, Marburg viruses |

BSL-3 plus: Clothing change before entering Chemical shower for suit, followed by personnel shower on exit Laboratory clothing and all material decontaminated on exit from facility |

Primary barriers: All procedures conducted in Class III BSCs or Class II BSCs in combination with full-body, air-supplied positive pressure suit HTS equipment cannot disrupt BSC air flow HTS and other equipment are surface decontaminated before removal from BSC Assay plates are surface decontaminated and transferred to a tray on a cart for transport outside of the BSC Plates are sealed and surface decontaminated before transport to the plate reader, as above |

Additional PPE movement restrictions Operational time in laboratory restrictions Equipment decontamination by formaldehyde for facility removal Facility entry restricted to qualified maintenance technicians on staff Maintenance and repair by FSE requires decontamination of equipment and removal from facility |

Ag, agricultural; BSC, biological safety cabinet; BSL, biosafety level; HTS, high-throughput screening; PAPR, powered air-purifying respirator; PPE, personal protective equipment.

HTS Evolution for Infectious Disease Screening

Many infectious disease screening programs now make use of phenotypic assays for broad antimicrobial drug discovery by employing replication-competent pathogens to assay compounds in physiologically relevant cell-based models. A decade ago, HTS operations using infectious pathogens were infrequent. Automated dispensing of compounds, cells, and infectious agents was done using a conventional liquid handler, such as a Biomek 2000 (Fig. 1A). To comply with biosafety requirements and to ensure sterility for cellular assays, these instruments were housed in a BSC specifically modified to accommodate their weight and size. The commercial availability of these types of instruments was limited, but the adoption of HTS as a key step in the drug discovery process motivated instrument manufacturers to develop many new types of dispensers that were better suited for use in biocontainment laboratories. Early infectious disease HTS efforts were directly adapted from manual antiviral or antimicrobial assay formats and conducted in 96-well microplates by automating the low-throughput steps. For example, manual procedures specified that eukaryotic cells were dispensed to the assay plates, then incubated overnight, and allowed to form an attached monolayer before the addition of test compounds. After the addition of compounds, the assay plates were transported into the BSC for the addition of virus. This process involved moving each assay plate to and from the incubator multiple times, which altered plate temperature and media pH and contributed to increased assay variability. In addition, it provided multiple opportunities for plate mishandling (e.g., to accidently drop plates), which contributed to reduced biosafety. In addition, the commercial availability of reagents for rapid assay endpointing was also limited. For early HTS, reagents that allowed cell-based assay endpoint development in a single step (i.e., add and read) were not available, so endpoints were frequently cell viability based and utilized MTS [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium] or similar reagents, which required plate handling and added additional time to the process. Due to these factors, throughput using this process was limited to less than 50 plates (∼4,000 compounds) per day.

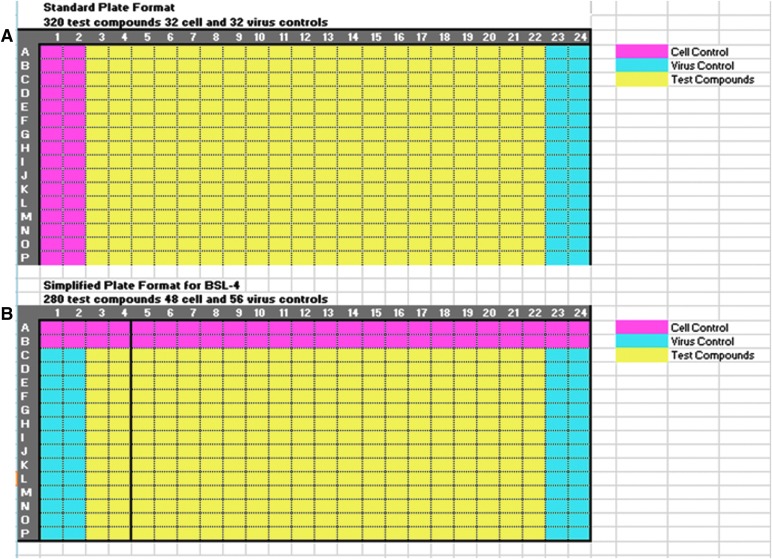

Fig. 1.

The optimization of high-throughput screening (HTS) liquid handler size. (A) Shows the relative size of the Biomek 2000 that was used in early infectious disease screening in biosafety level BSL-2 laboratories. Later efforts that were adapted to BSL-3 and -4 laboratories made use of smaller noncontact dispensers, such as the Matrix WellMate (B).

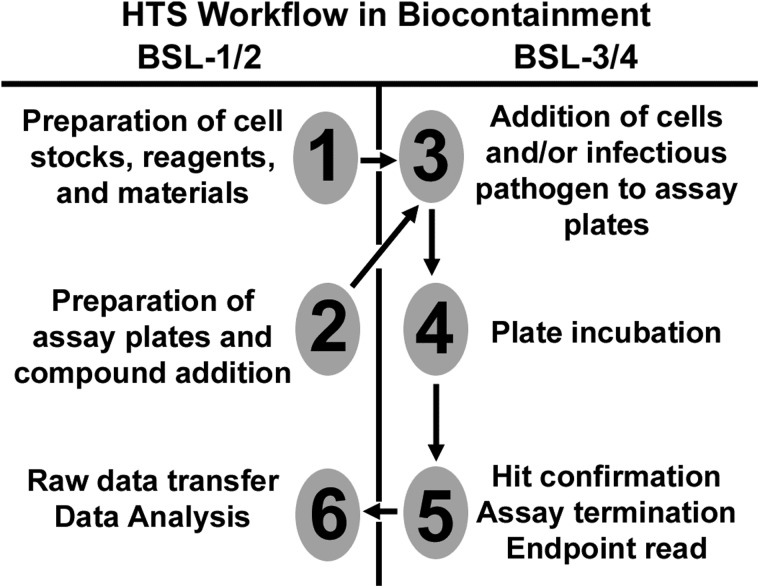

Successful infectious disease HTS campaigns at BSL-25–13 provided an ideal starting point to test modifications to the BSL-2 process with the goal of making the assays more operationally streamlined and efficient for BSL-3 and BSL-4 laboratories. The process improved when reagents were developed for an add and read endpoint and the large liquid handler was replaced with a small-footprint, portable noncontact dispenser (Fig. 1B).14 The next process improvement came by miniaturizing cell-based assays from a 96- to 384-well microplate, which simultaneously reduced reagent use and increased throughput. The next improvement was to change the order of compound and reagent additions. Predrugged assay ready plates (ARPs) were prepared by adding diluted compound to each well. Adding cells, followed by pathogen with minimal delay to ARPs, streamlined the process for infectious pathogen assays to the point where batches of approximately one hundred 384-well microplates (∼32,000 compounds/day) could be prepared with minimal plate manipulations and increased assay reliability and robustness. The process was further streamlined for antiviral assays by combining host cells with virus before dispensing to the assay plates. Cell controls were added using a separate dispenser. These methods were used to screen a large number of assays in both the BSL-2 and the BSL-3 containment laboratories,9–11,14–19 To minimize the number of plate manipulations further for screening in the BSL-4, the addition of cell controls and cells plus virus was combined into a single dispense step. Separate reservoirs of cells or mixed cells and virus were prepared, and these were added to the plates in a single pass by separating one line of the dispense cassette head to be used for the cell control with the balance of the lines used for dispensing of the cell plus virus mixture. Figure 2 compares these two plate layouts. The next process improvement was to prepare ARPs that could be stored for extended periods of time before use so that plates could be frozen, shipped, and stored until they were needed. This process required that nanoliter volumes of compound in 100% DMSO be dispensed to the plate. Initially, pin tools were used for this process, but variability was a problem with this method. The development of acoustic liquid handlers allowed ARPs to be prepared temporally and spatially apart from the assay set up with much greater accuracy. Each of these process and instrument improvements brought infectious pathogen screening to the level of efficiency that supported HTS in a BSL-4 laboratory.20

Fig. 2.

Assay plate layout. Compound library plates contain 320 compounds in columns 3–22 rows A–P as indicated in yellow (A). Columns 1, 2, 23, and 24 are empty to accommodate assay controls. For antiviral screening in the BSL-3, compounds are transferred to the assay plates and DMSO is added to the control wells. Cell controls are added to column 1 and 2 with one dispenser, and cells plus virus mixed together are added to columns 3–24 with another dispenser (A). For screening in the BSL-4, this process was simplified further so that all components could be added with one dispenser in a single pass. This format is illustrated in (B). One line of the dispense head is used to dispense cells into the cell control wells (row A, B), while the remaining lines, which are in a separate reservoir, contain cells and virus mixed together, which are dispensed to the remainder of the plate that includes test compounds and virus control wells (B).

Additional efficiency improvements involved the use of high-density frozen cell stocks as reagents for both bacterial and antiviral assays. The process of using stocks of cryopreserved cells directly in the assay alleviates cell culture variability due to passage and other culturing variables.21 Cells to be used directly from frozen stocks are prepared by expanding cells in culture up to a large number of flasks that are all of the same passage. Cells are then harvested, concentrated, rate frozen and stored in the vapor phase of liquid nitrogen until used. When the assays are performed, the frozen cells from a single passage provide a uniform biological response throughout extended screening campaigns without the variability that comes from multiple cell culture preparations.21 These methods have been used to support batch runs of several hundred 384-well plates of cells per day. When possible, the use of cryopreserved cells is the preferred method for cell supply as it streamlines the process and reduces variability and cost. However, cryopreserved cells do not work for all cell types in all assays. The HTS Center has successfully run screens using cryopreserved cells with HepG2 cells in an respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) assay and with Vero cells in the Nipah virus assay.20,22 Cells that have not worked directly from frozen stocks include HEK293 and THP-1 cells. Therefore, it is important to evaluate cryopreserved cells for direct use by monitoring cell viability and growth and that comparisons are made during antiviral assay validation to ensure that assay performance is consistent whether using frozen or cultured cells.

These process improvements will be implemented in more BSL-3 and BSL-4 laboratories as they gradually acquire HTS capabilities. Although the need for biosafety and the space-limiting personal protective equipment (PPE) will likely continue to affect the throughput of such laboratories (meaning that it is quite likely that biocontainment laboratories may never see the ultra-HTS performance levels that biochemical laboratories can achieve), HTS personnel will rapidly become accustomed to working in the biocontainment environments necessary for screening a broad range of live pathogens.

Operational Considerations for HTS at BSL-3/-4

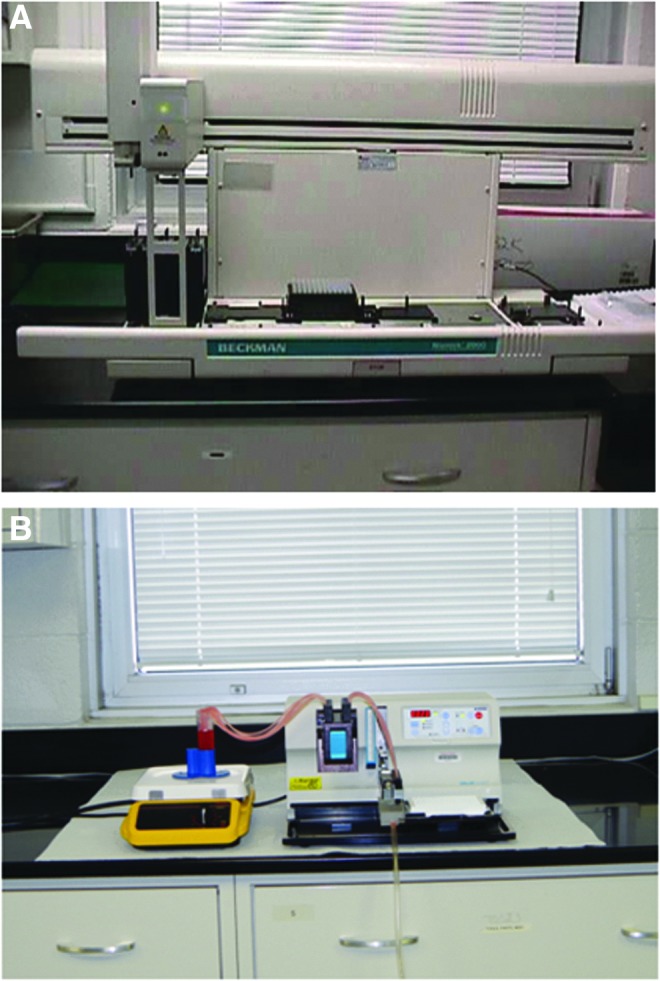

Special operational considerations are required for HTS in high-containment laboratories, and these are summarized in the far right column of Table 1. In addition to regulatory biosafety requirements, the operational processes for HTS in high containment (BSL-3 or -4) must be thoroughly established to ensure high-quality repeatable results. Since the biocontainment operations that directly involve the live pathogen are most difficult, time-consuming, and restrictive, it is reasonable to design a program that allows the majority of operations to be performed at the lowest required biocontainment level. Operations that can be done at lower biocontainment typically include all noninfectious steps, such as cell and reagent preparation, compound library manipulations, and data analysis. Steps that require high biocontainment include any direct work with the pathogen, such as assay preparation, assay incubation, and data acquisition. This requires the pairing of at least two dedicated laboratories for the global HTS effort. The first laboratory should be a BSL-2 laboratory for preparation of the reagents, cells, and needed assay materials, as well as compound manipulation and plating. The second laboratory should be a BSL-3 or -4 laboratory where the work with the infectious pathogen takes place. Table 2 lists the stages of process design and execution and the separation of tasks in each type of containment. In addition, other considerations (laboratory engineering controls for biosafety, operator and equipment requirements, PPE restrictions, and data control) are discussed below.

Table 2.

Process Development Hurdles for High-Containment High-Throughput Screening

| Process stage | Low-biocontainment laboratory tasks | High-biocontainment laboratory tasks |

|---|---|---|

| Design and development | Regulatory approval request from IBC | Performance of hands-on agent-specific training |

| Selection of pathogen and assay format | Establishment and optimization of assay conditions | |

| Performance of written agent-specific training | Establishment of optimal endpoint | |

| Diagram process design and flow | Evaluation of control parameters | |

| Generation of protocols and SOP | Evaluation of assay performance | |

| Validation, performance, and confirmation | Cell culture | Define assay variability |

| Reagent preparation | Assay execution | |

| Compound plating | Data collection | |

| Analyze data | Equipment decontamination Waste disposal |

Liquid Handling Systems for Streamlined Operations

Noncontact liquid dispensers with disposable or removable dispense cartridges should be used to facilitate decontamination. Because decontamination of liquid channels by chemical means is difficult to validate for efficiency, the use of removable liquid channel cartridges is very advantageous in high-containment environments. These cartridges, if disposable, can be discarded after chemical decontamination without concern for carryover of the chemical decontaminant into the next assay. The WellMate from Thermo Matrix (Hudson, NH) is a small-footprint noncontact liquid dispenser with an 8-channel disposable cartridge that can be used for 96- and 384-well microplate formats. Cartridges feature a flexible 8-channel design that can be easily modified to dispense multiple solutions into a plate simultaneously, enabling addition of various reagents in a single pass. It has been extensively evaluated in several BSL-2 through -4 HTS efforts.14,16,17,20,22,23 The WellMate cartridge dispense tips are separate from the tensioning mechanism, which allows the dispense tips to be removed from the holder and placed in a reservoir of decontaminating solution to externally decontaminate the tips before the assembly is removed from the instrument, providing additional safety for the operator. If cartridges are not considered disposable, then they need to be chemically decontaminated and then washed extensively to remove the chemical decontaminant before removal from the instrument. The dispense head is then bagged and autoclaved before reuse. Cassette heads have a limited number of autoclave cycles at 121°C before the dispense accuracy is affected. In some BSL-3 and -4 facilities, the autoclaves are set to achieve higher temperatures for decontamination of waste. Autoclaving at temperatures above 121°C can affect dispense head performance quickly and should be taken into consideration when selecting a dispenser for use in biocontainment. An instrument with nondisposable dispense heads is the Multidrop Combi dispenser from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA), which is able to dispense to 96-, 386-, and 1,536-well microplate formats. The cartridge for this instrument is not considered disposable, but is still removable and autoclavable for efficient decontamination. Additionally, the dispense tips are integrated into part of the tensioning assembly, which makes it difficult to externally decontaminate the dispense tips before removing the cartridge from the instrument. For work with hazardous pathogens, this should be taken into consideration when selecting a dispenser.

For compound preparation, conventional liquid handlers with disposable tips have been used extensively for HTS. Recently, the use of acoustic-based dispensers that have no liquid contact at all has become available. For example, the Echo acoustic dispenser from Labcyte (Sunnyvale, CA) uses sound waves to dispense 2.5 nL droplets from a source to a destination plate. Acoustic dispensing has been used to prepare ARPs for HTS campaigns,20 but has also been used to dispense bacteria for a motility assay11 and virus particles for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) (unpublished data). However, like other large complex liquid handlers, it is not suitable for use in the BSL-3 or -4 due to size and service limitations.

Preservation of Facility Engineering Controls

Engineering controls play a critical role in preventing the release of pathogenic agents in high-containment laboratories.24 Controlled ventilation, such as laboratory-negative air pressure, air curtains provided by BSCs, and facility HEPA filtration, provides one of the most effective engineering controls. While the use of HTS equipment does not typically affect the global airflow within laboratories, the size and location of the equipment does have the potential to disrupt local airflow. For example, the automated HTS liquid handlers and dispensers that are used to prepare assay plates and dispense pathogen-containing solutions will generate aerosols during their operation and, therefore, must be contained within a BSC. When placing a large piece of equipment inside a BSC, two major factors must be considered. First, the BSC must be large enough to completely contain the equipment and still provide reasonable work space inside the cabinet. Second, the size of the equipment should not decrease the operator level of protection by disrupting the air curtain provided by the BSC. Preservation of the engineering controls in a high-containment HTS laboratory is more readily accomplished by the use of wider and deeper BSCs (1.8 m instead of 1.2 m width and 0.25 m extra depth), equipment with reduced space requirements (small footprint), and modular laboratory designs (mobile equipment and benchtops) for maximum process flexibility. Moving large, heavy pieces of equipment to and from fixed benches creates the opportunity for accidents and exposures in a containment laboratory. Mobile workstations for larger equipment, like plate readers, facilitate moving the equipment into the airlock when moving the instrument into the containment laboratory or for decontamination of the equipment to remove it from the biocontainment laboratory.

Agent-Specific Training for Operators

Before working with any pathogen, biosafety and regulatory compliance must be reviewed with operators to minimize the risk of working with infectious agents.4 This includes agent-specific training for routes of transmission, incubation period, signs and symptoms of disease, prophylaxis and therapy, and effective decontamination procedures. The use of automated HTS equipment in high-containment laboratories creates a different set of risks than manual operations that need to be specifically addressed to ensure safety. Additional instrument-specific training should include proper equipment operation, troubleshooting, decontamination, and safety issues associated with automated devices that have motor driven moving parts which have the potential for physical injury if used improperly. Before working in high-biocontainment laboratories, operators are trained extensively at BSL-1 and BSL-2 using identical equipment. Safety is paramount in high-containment laboratories and any change in the process and/or equipment needs to be evaluated in the BSL-1 or -2 environment before implementation in high containment. In addition to agent-specific training, flexible facilities-specific training is also necessary for HTS operations in biocontainment. BSL-4 laboratories operate using firm guidelines and rules that government regulatory agencies have specified as required for all BSL-4 pathogens, but many BSL-3 laboratories have operations that are variable depending on the nature of the work and the pathogens utilized. This will affect the PPE that operators wear, the time allowed for operators to stay in the laboratory without exiting for rest, and the decontamination procedures for removing items, samples, and equipment from the laboratories. For example, experimentation at BSL-3 with Bacillus anthracis requires that the operators wear an N-95 respirator, but experimentation at BSL-3 with highly pathogenic avian influenza requires that the operators wear a powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR), along with additional training and engineering controls that enhance biosafety.

Maintenance and Repair of HTS Equipment

Because of the cost and effort required for movement of materials and equipment in and out of high-containment laboratories, dedication of HTS equipment for long-term or permanent use inside the biocontained facilities is highly desirable since it avoids frequent decontamination and movement of equipment in and out of a containment facility. Each method of decontamination requires that the equipment be exposed for an extended period of time (h) to a highly reactive or corrosive chemical vapor for the destruction of microbial life. The same chemical exposure can also be very destructive to the electronic components and optics, and therefore, decontamination cycles should be kept to a minimum to avoid shortening the life of valuable equipment. Routine equipment maintenance is often performed by a factory-trained service professional, but many factory service professionals are barred (because of medical surveillance and biosecurity restrictions) or refuse to enter high-containment facilities, so equipment must be removed from high containment and decontaminated for maintenance or repair. This is a critical factor in the selection of equipment for use in a high-containment laboratory. Large devices that are difficult to move, complex instruments that need frequent service support, or equipment that must be installed by a service engineer are not suitable for use in containment laboratories. Small robust instruments that can be maintained and repaired by the operator are a better choice for this application. Physically moving the equipment to and from its site of operation also means that it must not require a service person to set it up for operation. To minimize equipment damage from decontamination while preserving the routine maintenance schedule for the facility and the HTS equipment, decontamination and maintenance of equipment are often coordinated with regulatory-required annual shutdowns of the BSL-3 or -4 facilities. This allows service personnel to safely enter the facility or for equipment to be removed from the facility for maintenance. In addition, training in advanced equipment maintenance should be given to high-containment laboratory staff who can troubleshoot and repair equipment as needed. Real-time cameras with a clear view of the equipment as well as the networking of instrument computers can assist more experienced technical personnel in directing troubleshooting operations from outside of containment, but for security reasons, there may be limitations on this type of access.

Personal Protective Equipment Restrictions

Operations at BSL-3 or -4 require additional PPE to reduce the risk to the operators for accidental infection.4 Common additional PPE items for work in the BSL-3 include respiratory protection (N-95 mask or PAPR) and disposable multilayer garments (additional gloves, boots, scrubs, disposable suits, and gowns). For work in the BSL-4, complete barrier protection (pressure suit with externally supplied air) is required. Figure 3 illustrates the changes in PPE required for operator safety at BSL-2, −3, and -4. Selection of equipment for use in containment laboratories should be compatible with the required PPE. Preservation of manual dexterity when choosing gloves (which for BSL-4 are much heavier than standard laboratory latex or nitrile gloves), visibility of displays when instruments are inside a BSC (displays on some instruments are obstructed when placed in a BSC), and hearing (while the operator is wearing a PAPR or isolation suit, audible signals may not be loud enough to hear due to the noise produce by the PPE) should be important considerations. Enhanced levels of PPE make it more difficult to operate with precision, which has the potential to affect the experimental results and to increase operational risks. This impact of PPE is offset by rigorous operator training that instills patience and attention to detail during experimentation. The consequence is that all experiments require extended time in high containment because greater care is necessary to conduct them. Because operators are frequently limited to 4–8-h periods in the laboratory before exit, more operators than usual may be required for lengthy experiments. Alternatively, experimental times must be shortened or parsed to account for operator fatigue.

Fig. 3.

The amount of personal protective equipment (PPE) increases with BSL. An operator at a class II biosafety cabinet is shown at BSL-2, BSL-3/3+, and BSL-4. The differences in PPE (described in Table 1) are shown for each level. The operator is shown manipulating a small-footprint noncontact liquid dispenser.

Data Acquisition, Transfer, and Storage Requirements

HTS operations require electronic transfer of data from the point of acquisition to a database for storage and processing. This is accomplished through local area networks (LANs) for transfer of data within an organization and the internet for transfer of data between organizations. Transfer of data from the containment laboratory to the LAN is usually accomplished through a hard wired connection because wireless transmitters cannot penetrate the concrete walls that house these types of facilities. Data security is a concern and should be managed by the organization information technology group. Once data are retrieved from the containment laboratory, it is processed using standard bioinformatic methods.

Other Considerations

Government regulatory agencies have mandated rules and regulations governing work in BSL-3/-4 laboratories. It takes a coordinated effort by the institutional environmental health and safety staff, the biosafety committee, facility manager, and the responsible investigator to maintain and update programs to comply with current regulations. For example, local Institutional Biosafety Committees are frequently chartered for oversight and approval of biosafety operations as well and should be included as early as possible in the process for guidance and approval of HTS processes within BSL-3 and -4 laboratories. Institutional Biosafety Committees may differ in their interpretations of the BMBL requirements and/or wish to add additional layers of safety to the operation, any of which could affect HTS operations in containment. A biosafety oversight example might be handling of microtiter plates containing infectious material when they are being moved from the BSC to another location, such as an incubator or a plate reader, within the containment laboratory. This may involve sealing and surface decontamination of the plate before removal from the BSC or use of secondary containment for transport of unsealed plates. If assay plates need to be removed from the containment facility, then the IBC and EHS personnel are involved with determining what the proper decontamination process should be. Such requirements could affect the quality of the results and/or the number of plates that can be processed within a work day. One compliant solution is to seal the microtiter plates and surface decontaminate them in the BSC before reading them on the plate reader. This requires that the plate reader be capable of bottom reading the assay endpoint or that optically clear seals be used. Stackers should not be used because they can pose a safety risk (plate jammed inside of an instrument requiring decontamination) and add complexity to the instrumentation (which can increase instrument down time and increase service calls). Laboratory space within high containment is highly constrained, limiting the number of people and pieces of equipment in a room. This makes the standard BSL-1 and -2 procedures to increase throughput by duplicating equipment and/or increasing personnel either extremely costly or impossible to achieve. Now that computers are widely used to control laboratory equipment and collect data, it is possible to remotely access these computers for technical support from a remote location. This is done routinely using Webex (Cisco, San Jose, CA) or by using software like pcAnywhere (Symantec, Mountain View, CA) to allow access to computers for the purpose of troubleshooting software or equipment problems by trained personnel who do not have physical access to the computer. This is an extremely powerful technology that can quickly resolve a technical problem and prevent failed screening runs, but information security concerns might also prohibit remote access to computers inside the containment facility, making data transfer and equipment troubleshooting and repair more difficult. Finally, having duplicate equipment outside the containment laboratories allows for technical personnel to be trained in the best use and troubleshooting of the equipment without the restrictions imposed by working under high containment.

Process Design and Development For BSL-4 HTS

BSL-4 containment is the highest level of biocontainment and is reserved for dangerous and exotic biological agents, which pose a high individual risk of aerosol-transmitted laboratory infections and life-threatening disease to workers.4 They may present a high risk of spreading to the community and there is usually no effective prophylaxis or treatment available. These pathogens are primarily hemorrhagic and encephalitic fever viruses such as Ebola, Marburg, and Nipah. There is currently immense global pressure to conduct therapeutic research and discovery for these viruses to combat current epidemic conditions in endemic areas of the world. The expansion of HTS to BSL-4 laboratories would greatly aid in this task. However, operations in BSL-4 laboratories present the greatest challenges to HTS efforts with infectious pathogens. To circumvent the need to conduct HTS in a BSL-4 laboratory, a number of strategies have been employed to enable screening at primarily the BSL-2. These include the use of surrogate or attenuated viruses, pseudotyped viruses, screens based on noninfectious virus-like particles (VLPs), and minigenome or replicon systems.25–27 While these strategies have enabled HTS to be performed with these pathogens at facilities that do not have access to BSL-4 laboratories, the concern is that these artificial systems may not accurately reflect all the antiviral targets of the virulent pathogen.28 BSL-4 work has historically been low throughput, relying on visual observation of cytopathic effect (CPE) and quantitation of virus titer by plaque assay or by qPCR. These manual processes are not scalable to the levels of throughput needed to conduct HTS campaigns.28 Recently, high-content imaging was used with Ebola VLPs to screen compound libraries at BSL-229 and for several BSL-4 pathogens,30 but the actual imaging of the samples was conducted at the BSL-2. This required extensive fixation of samples to inactivate the virus before removal from containment. High-content screening (HCS) has not been fully adapted to BSL-4 due to the difficulties of maintaining such complex instruments in high containment or the need to process the samples to remove them from the containment laboratory. Therefore, the development of high-throughput bioassays that can employ infectious, replication-competent wild-type pathogens in a BSL-4 environment would be a significant advancement that would remarkably streamline and hasten the drug discovery process.

While there are multiple reports of automated HTS performed at BSL-3,9,13,16–19,31,32 there is only a single report of true automated HTS assays in BSL-4 biocontainment.20 This represents a paradigm shift on how drug discovery for highly pathogenic BSL-4 infectious agents can be done. It is now possible to screen hundreds of thousands of compounds in weeks for antiviral activity using the actual pathogen. Lower throughput non-automated assays at BSL-4 have been reported, but their formats have not been fully adapted to automated HTS. Typical platforms have previously incorporated assays performed at BSL-4, followed by removal of plates from the BSL-4 and subsequent analysis of virus replication at BSL-2.33,34 However, removal of plates from high biocontainment requires rigorous decontamination of the assay plates (cell fixation and virus inactivation), which can compromise the results. In addition, the number of manipulations and the transfer of microtiter plates out the BSL-4 make this method logistically impractical for processing large numbers of plates or for process automation.

Recently, a Nipah virus cell-based assay was used to implement a semi-automated HTS platform at BSL-420 with the goal of producing an assay capable of screening 10,000 compounds per run. The effort was a collaboration between the Southern Research (SR) and Galveston National Laboratory (GNL), which is part of the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston. This platform allows the screening of wild-type virus strains instead of pseudotype, surrogate, or recombinantly attenuated viruses that have been downgraded for use at lower biocontainment levels.20 The throughput of the HTS assay is considerably greater than the previous reports of assays using BSL-4 pathogens, with screening of up to 10,000 small-molecule compounds, in a single-dose format, or up to 1,000 hit compounds for concentration-dependent response, per run. This platform provides for rapid drug evaluation, hit identification, and characterization (defining EC50 and selectivity values for potential antiviral therapeutics). Table 2 outlines the steps undertaken for performance of a general HTS assay in BSL-4 containment laboratories. These steps are discussed below.

The HTS Nipah virus assay was a phenotypic screen for inhibitors of the CPE induced in Vero cells by Nipah virus infection. The endpoint was cell viability and a luminescent, one-step detection reagent was used. Initially, all the processes, procedures, and safety considerations were submitted to the Institutional Biosafety Committees of both organizations for review and approval. A risk assessment of the pathogen with respect to its transmissibility and the type of containment required within the BSL-4 was performed. In accordance with regulatory requirements, the PPE worn by operators was a pressure suit (Fig. 3), which provided a significant level of protection. Once approval was met, the actual development and optimization of the assay and evaluation of the flow of work outlined were undertaken. The initial step involved GNL laboratory personnel traveling to SR for extensive training, which could be conducted at BSL-2, for use and simple maintenance of the equipment. Reciprocally, the SR HTS Center supervisor traveled to GNL to oversee the set up and use of the equipment that was to be used in the BSL-4. Mock assays with BSL-2 pathogens were run in both locations (SR and GNL) before equipment was moved into the BSL-4. The liquid handling equipment that dispenses the virus and cell dilutions into drugged plates was placed in a BSC. However, because of space restrictions, the plate reader for reading the endpoints was kept outside the BSC. Because there was the inherent risk of plates dropping or becoming jammed in the reader, plates were sealed in the BSC and surface decontaminated before reading. Therefore, the combination of plastic adhesive seals, PPE, BSC, and training acted as sufficient barriers to accidental exposure.

Once the protective barriers were in place, the next step in the establishment of the screen was to define the optimal flow of work (Fig. 4). The restrictions of working in BSL-4 containment required a simplified assay design. To minimize plate handling in the BSL-4 facility, ARPs were prepared at SR. Plates were sealed, frozen, and shipped to the GNL on dry ice. Once in the BSL-4 containment facility, all remaining components were added in a single pass to minimize plate handling. Virus and cells were mixed and dispensed using a flexible, noncontact liquid handling system in a class II BSC within the BSL-4 laboratory. This was accomplished by dispensing the Vero cell controls from one reservoir using one line of the dispenser and dispensing the cells mixed with a virus from another reservoir using the remaining dispenser lines. The BSL-4 plate layout is illustrated in Figure 2B. The plates were incubated for 3 days, equilibrated to room temperature for 30 min, and an equal volume of endpoint reagent added. Plates were incubated for additional 10–15 min at room temperature, sealed, surface decontaminated, and then read with a plate reader in luminescence mode. In the GNL work flow, plates were prepared and analyzed in groups of first 12 and then 24 plates per run to test the process under actual BSL-4 conditions before attempting to increase the throughput. However, with validation of the process in the BSL-4 HTS laboratory completed, it is projected that up to 50 plates per run can be processed effectively, using two operators. This translates to 14,000 compounds per run and 2 runs per week for a 3-day assay such as the Nipah screen. Financial rather than logistical constraints limited the number of compounds that were screened in the Nipah and, an unpublished, Ebola pilot HTS projects.

Fig. 4.

The optimized HTS workflow for BSL-3/-4 containment laboratories. Six operational steps are outlined, separated by performance in low-containment (BSL-1/-2) or high-containment (BSL-3/-4). These steps are designed to minimize plate handling, operator workload, and equipment dedication in high-containment laboratories.

Future Directions

The adaptation of HTS to the BSL-4 environment and the successful pilot screens for two different BSL-4 virus pathogens creates an opportunity for true HTS efforts for Ebola and Nipah viruses, which is one of first steps in traditional drug discovery programs. It also means that the same strategy could be applied to other BSL-4 pathogens, such as Lassa, Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever, and Junin viruses, in addition to highly pathogenic emerging viruses. Looking ahead, throughput for HTS assays conducted in high-containment laboratories could be improved by going to higher density 1,536 microtiter plates in place of the currently used 384 version. Bacterial and yeast assays have been conducted at BSL-223 in a 1,536-well microplate format and short-term viral assays also have the potential to be done in this format; each of these could be implemented in higher containment laboratories when the throughput is needed. New technologies present an opportunity to bring different types of assays into HTS for infectious agents. Multimode plate readers have been used to monitor a wide variety of endpoints, including fluorescence, absorbance, fluorescence polarization, and luminescence, proximity-based endpoints like fluorescence resonance energy transfer or alphascreen and time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer. The use of high-content images has recently been incorporated into the HTS process. Moreover, while this is possible in BSL-2 containment laboratories, it is not practical to have the current generation of HCS instruments in higher level containment laboratories. The instruments are large and require significant service support, both of which are impractical in a BSL-3 and BSL-4 laboratory. What is practical are laser scanning cytometers, which can perform many HCS-type assays using a small robust instrument that is no more difficult to manage than a multimode plate reader and almost as fast. Instruments like the TTP Acumen and Mirrorball and the Molecular Devices Velos fall into this category. The Mirrorball is unique in that it is a laser scanning cytometer with a narrow field of focus. This enables plate-based FACS and ELISA style assays in a no-wash format. This instrument has been used to monitor cell surface expression of viral proteins by addition of an antibody, specific to the viral protein of interest, directly to the assay plate. This is followed by addition of a fluorescently labeled secondary antibody. The plate is then imaged on the laser scanning cytometer to detect cell-associated fluorescence as a measure of viral infection. This can be done without a fixing step or any wash steps. It has also been used to monitor virus infection and the spread of a GFP expressing virus (unpublished data). This is an enabling technology that will allow development of HTS assays for viruses that do not produce CPE or cannot be modified to express a reporter gene. It can also be used to monitor expression of fluorescent proteins in engineered viruses or cell lines, expanding the types of assays that can be applied to antiviral drug discovery. Another technology that has become more common in HTS applications is qPCR, where it has been used as a secondary assay to monitor mRNA levels in compound-treated cells. At the SR HTS Center, qPCR technology has also been used to quantify the number of virus particles directly from the supernatant taken from infected cells. This provides a way to monitor virus titer reduction as an assay endpoint. Development is underway to adapt this technology to qPCR in a 1,536-well format for screening in the BSL-2 laboratory. For high-containment laboratories, the 384-well format may be the practical limit and while that might not be high enough throughput for an HTS campaign, it would be a powerful counter screen for compounds identified in the other types of assays described here.

The recent outbreak of Ebola virus underscores the importance of both vaccine and drug development for these emerging and highly pathogenic agents. The ability to respond rapidly with a robust drug discovery effort will be critical for responding to emerging pathogens. As with the development of other antiviral drugs, it is anticipated that the drug-resistant strains of these pathogens will emerge and hence continued drug discovery efforts will be needed.

Summary

It is possible to conduct HTS campaigns up to the highest level of biocontainment. This capability presents an opportunity for modern drug discovery methods to be applied to some of the most deadly pathogens in the world. The recent and ongoing outbreak of Ebola virus infection in West Africa underscores the need to develop therapeutics for these pathogens and the fastest way to do this is to use the proven methodology of modern drug discovery. There are difficulties and limitations to working at the BSL-4, but the process that is reviewed here demonstrates that it can be done. Drug discovery and development are expensive and this will be even more expensive working in high-level containment laboratories. The greatest barrier to success is not the limitation and regulation of working in containment, but procuring the financial resources to do the work that is needed to produce a therapeutic.

Abbreviations Used

- ARP

assay ready plate

- BMBL

Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories

- BSC

biological safety cabinet/biosafety cabinet

- BSL

biosafety level

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CPE

cytopathic effect

- EC50

concentration giving half maximal effect

- EHS

Environmental Health and Safety

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- GNL

Galveston National Laboratory

- HCS

high-content screening

- HTS

high-throughput screening

- IBC

Institutional Biosafety Committee

- LAN

local area network

- PAPR

powered air-purifying respirator

- PPE

personal protective equipment

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- RSV

respiratory syncytial virus

- SR

Southern Research

- USDA

United States Department of Agriculture

- VLPs

virus-like particles

Acknowledgments

The funding for this work has been provided by NIH-NIAID awards N01 AI 15449 “Microbiological Drug Screening,” N01-AI-30047 and HHSN2722011000009C “In Vitro Antiviral Screening,” U19Al109664 “Therapeutics Targeting Filoviral Interferon-antagonist and Replication Function,” and the NIH Roadmap Initiative U54 HG003917 and U54 HG005034.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Noah JW: New developments and emerging trends in high-throughput screening methods for lead compound identification. Int J High Throughput Screen 2010;1:141–149 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emmert EA: Biosafety ASMTCoL. Biosafety guidelines for handling microorganisms in the teaching laboratory: development and rationale. J Microbiol Biol Educ 2013;14:78–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Health and Human Services: Requirements for facilities transferring or receiving select agents. Final rule. Fed Regist 2001;66:45944–45945 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL) 5thEdition United States Government Printing Office, 2009. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/biosafety/publications/bmbl5/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atkins C, Evans CW, White EL, Noah JW: Screening methods for influenza antiviral drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2012;7:429–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falk SP, Noah JW, Weisblum B: Screen for inducers of autolysis in Bacillus subtilis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010;54:3723–3729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beer B, Snyder B, Luckenbaugh K, Lackman-Smith C, Hogan P, Ptak R, Shindo N, Rasmussen L, White EL, Brelot A, Alizon M: Development of a CCR5-tropic HIV-1 fusion assay amenable to high-throughput screening for topical microbicides. Retrovirology 2006;3(Suppl 1):S84 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Q, Maddox C, Rasmussen L, Hobrath JV, White LE: Assay development and high-throughput antiviral drug screening against Bluetongue virus. Antiviral Res 2009;83:267–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maddry JA, Chen X, Jonsson CB, et al. : Discovery of novel benzoquinazolinones and thiazoloimidazoles, inhibitors of influenza H5N1 and H1N1 viruses, from a cell-based high-throughput screen. J Biomol Screen 2011;16:73–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore BP, Chung DH, Matharu DS, et al. : (S)-N-(2,5-dimethylphenyl)-1-(quinoline-8-ylsulfonyl)pyrrolidine-2-carboxamide as a small molecule inhibitor probe for the study of respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Med Chem 2012;55:8582–8587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rasmussen L, White EL, Pathak A, et al. : A high-throughput screening assay for inhibitors of bacterial motility identifies a novel inhibitor of the Na+-driven flagellar motor and virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011;55:4134–4143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang L, Nebane NM, Wennerberg K, et al. : A high-throughput screen for chemical inhibitors of exocytic transport in yeast. Chembiochem 2010;11:1291–1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung D, Schroeder CE, Sotsky J, et al. : ML336: development of quinazolinone-based inhibitors against venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV). In: Probe Reports from the NIH Molecular Libraries Program. Bethesda, MD, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noah JW, Severson W, Noah DL, Rasmussen L, White EL, Jonsson CB: A cell-based luminescence assay is effective for high-throughput screening of potential influenza antivirals. Antiviral Res 2007;73:50–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung DH, Moore BP, Matharu DS, et al. : A cell based high-throughput screening approach for the discovery of new inhibitors of respiratory syncytial virus. Virol J 2013;10:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ananthan S, Faaleolea ER, Goldman RC, et al. : High-throughput screening for inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2009;89:334–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung DH, Jonsson CB, Maddox C, et al. : HTS-driven discovery of new chemotypes with West Nile Virus inhibitory activity. Molecules 2010;15:1690–1704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maddry JA, Ananthan S, Goldman RC, et al. : Antituberculosis activity of the molecular libraries screening center network library. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2009;89:354–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Severson WE, Shindo N, Sosa M, et al. : Development and validation of a high-throughput screen for inhibitors of SARS CoV and its application in screening of a 100,000-compound library. J Biomol Screen 2007;12:33–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tigabu B, Rasmussen L, White EL, et al. : A BSL-4 high-throughput screen identifies sulfonamide inhibitors of Nipah virus. Assay Drug Dev Technol 2014;12:155–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaman GJ, de Roos JA, Blomenrohr M, van Koppen CJ, Oosterom J: Cryopreserved cells facilitate cell-based drug discovery. Drug Discov Today 2007;12:521–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rasmussen L, Maddox C, Moore BP, Severson W, White EL: A high-throughput screening strategy to overcome virus instability. Assay Drug Dev Technol 2011;9:184–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goller CC, Arshad M, Noah JW, et al. : Lifting the mask: identification of new small molecule inhibitors of uropathogenic Escherichia coli group 2 capsule biogenesis. PLoS One 2014;9:e96054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crane JT, Riley JF: Design of BSL-3 Laboratories. J Am Biol Saf Assoc 1999;4:17–23 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basu A, Mills DM, Bowlin TL: High-throughput screening of viral entry inhibitors using pseudotyped virus. Curr Protoc Pharmacol 2010;Chapter 13:Unit 13B.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bosio CM, Aman MJ, Grogan C, et al. : Ebola and Marburg viruses replicate in monocyte-derived dendritic cells without inducing the production of cytokines and full maturation. J Infect Dis 2003;188:1630–1638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jasenosky LD, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y. Minigenome-based reporter system suitable for high-throughput screening of compounds able to inhibit Ebola virus replication and/or transcription. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010;54:3007–3010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osiceanu AM, Murao LE, Kollanur D, et al. : In vitro surrogate models to aid in the development of antivirals for the containment of foot-and-mouth disease outbreaks. Antiviral Res 2014;105:59–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pegoraro G, Bavari S, Panchal RG: Shedding light on filovirus infection with high-content imaging. Viruses 2012;4:1354–1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mudhasani R, Kota KP, Retterer C, Tran JP, Whitehouse CA, Bavari S: High content image-based screening of a protease inhibitor library reveals compounds broadly active against Rift Valley fever virus and other highly pathogenic RNA viruses. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014;8:e3095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Severson WE, McDowell M, Ananthan S, et al. : High-throughput screening of a 100,000-compound library for inhibitors of influenza A virus (H3N2). J Biomol Screen 2008;13:879–887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reynolds RC, Ananthan S, Faaleolea E, et al. : High throughput screening of a library based on kinase inhibitor scaffolds against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2012;92:72–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Porotto M, Orefice G, Yokoyama CC, et al. : Simulating henipavirus multicycle replication in a screening assay leads to identification of a promising candidate for therapy. J Virol 2009;83:5148–5155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aljofan M, Porotto M, Moscona A, Mungall BA: Development and validation of a chemiluminescent immunodetection assay amenable to high throughput screening of antiviral drugs for Nipah and Hendra virus. J Virol Methods 2008;149:12–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]