Abstract

Objectives

To improve the approach to the diagnosis and management of urogenital tuberculosis (UGTB), we need clear and unique classification. UGTB remains an important problem, especially in developing countries, but it is often an overlooked disease. As with any other infection, UGTB should be cured by antibacterial therapy, but because of late diagnosis it may often require surgery.

Methods

Scientific literature dedicated to this problem was critically analyzed and juxtaposed with the author’s own more than 30 years’ experience in tuberculosis urology.

Results

The conception, terms and definition were consolidated into one system; classification stage by stage as well as complications are presented. Classification of any disease includes dispersion on forms and stages and exact definitions for each stage. Clinical features and symptoms significantly vary between different forms and stages of UGTB. A simple diagnostic algorithm was constructed.

Conclusions

UGTB is multivariant disease and a standard unified approach to it is impossible. Clear definition as well as unique classification are necessary for real estimation of epidemiology and the optimization of therapy. The term ‘UGTB’ has insufficient information in order to estimate therapy, surgery and prognosis, or to evaluate the epidemiology.

Keywords: bladder, classification, diagnosis, kidney, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, prostate, tuberculosis, urogenital

Introduction

According to World Health Organization (WHO) reports, reviewed in March 2014, about one-third of the world's population has latent tuberculosis (TB), which means people have been infected by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) but are not (yet) ill with disease and cannot transmit the disease [World Health Organization, 2014]. People infected with Mtb have a lifetime risk of falling ill with TB of 10%. However persons with compromised immune systems, such as people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), malnutrition or diabetes, or people who use tobacco, have a much higher risk of falling ill [World Health Organization, 2014].

TB is second only to HIV/AIDS as the greatest killer worldwide due to a single infectious agent. In 2012, 8.6 million people fell ill with TB and 1.3 million died from TB. TB is a leading killer of people living with HIV causing one fifth of all deaths [World Health Organization, 2014].

In 2012, the largest number of new TB cases occurred in Asia, accounting for 60% of new cases globally. Urogenital tuberculosis (UGTB) is a frequent form of TB, but it is a mostly overlooked disease. Despite major efforts to increase case detection, an estimated one-third of new TB cases are still being missed each year, and the unavailability of a rapid, low-cost, accurate diagnostic assay that can be used at the point of care is a major hindrance [World Health Organization, 2014]. There are a very few multicenter randomized studies on UGTB because of the absence of a unique approach to definition, diagnosis, therapy and management of this disease.

Terms and definitions

The first note of UGTB was made by Porter in 1894 [Porter, 1894]; in 1937 Wildbolz [Wildbolz, 1937] suggested the term genitourinary TB. The term UGTB is more correct, because kidney TB, which is usually primary, is diagnosed more often than genital TB. However, the term ‘urogenital tuberculosis’ includes many forms of TB with their own clinical features requiring their own therapy and management, so it is also incorrect.

UGTB: infectious inflammation of urogenital system organs in any combination, caused by Mtb or Mycobacterium bovis.

Urological tuberculosis (UTB): infectious inflammation of the organs of the urinary system in female patients and isolated or in combination with the genital system in male patients, caused by Mtb or M. bovis.

Genital tuberculosis (GTB): infectious inflammation of the female or male genitals, accordingly female genital tuberculosis (FGTB) or male genital tuberculosis (MGTB), caused by Mtb or M. bovis.

Kidney tuberculosis (KTB): infectious inflammation of kidney parenchyma, caused by Mtb or M. bovis.

Urinary tract tuberculosis (UTTB): infectious–allergic inflammation of calyx, pelvic and upper and lower urinary tract caused by Mtb or M. bovis.

Generalized urogenital tuberculosis (gUGTB): TB of kidney as well as GTB, male or female.

Etiology of UGTB

Mtb causes UGTB in 80–95% of cases. As TB is an antropozoonotic disease, M. bovis is actually too. Also, M. bovis is an etiological agent when BCG therapy for bladder cancer is complicated by bladder TB.

Classification of UGTB

Correct clinical classification allows optimal management and therapy to be defined.

Clinical classification of UGTB consists of [9]:

I. Urinary TB:

1. KTB (nephrotuberculosis)

• TB of kidney parenchyma (stage 1, nondestructive form) is subject to conservative therapy.

• TB papillitis (stage 2, small-destructive form) is subject to conservative therapy, reconstructive surgery is indicated for complications only.

• Cavernous KTB (stage 3, destructive form), recovery without surgery is rare.

• Polycavernous KTB (stage 4, widespread-destructive form), recovery with anti-TB drugs only is impossible, surgery is necessary, basically nephrectomy.

Complications of nephrotuberculosis: chronic renal failure, fistula, high blood pressure.

2. UTTB (TB of pelvis, ureters, bladder, and urethra) is always secondary to KTB. UTTB appears as an edema first, next stages are infiltration, ulceration, and fibrosis. UTTB is always secondary to KTB.

II. MGTB:

• TB epididymitis (unilateral or bilateral);

• TB orchiepididymitis (unilateral or bilateral);

• Prostate TB (infiltrative or cavernous forms);

• TB of the seminal vesicles;

• TB of the penis.

Complications of MGTB: strictures, fistula, infertility, sexual dysfunction.

III. FGTB (not included in this article).

IV. Generalized UGTB: simultaneous lesion of urinary organs and genitals, always considered complicated.

Mtb detection in urine is necessary for diagnosing KTB stage 1, but may not always be revealed in other forms of UGTB.

Characteristic of UGTB forms

KTB-1 has minimal lesions without destruction and full recovery is possible with anti-TB drugs. Intravenous urography (IVU) is normal. Urinalyses in children are often normal, but in adults low-level leukocyturia may be found. Usually patients have no complaints and are diagnosed by occasion. KTB-1 very rarely is complicated. Prognosis is good, outcome is usually full recovery. With inappropriate therapy KTB-1 may progress to a destructive form. Bacteriology confirmation of KTB-1 should be mandatory. Usually Mtb in KTB-1 patients is sensitive to anti-TB drugs.

KTB-2 may be unilateral and bilateral, solitary and multiple. KTB-2 is often complicated by UTTB. KTB-2 should be treated with anti-TB drugs; if complicated, reconstructive surgery is indicated. Prognosis is good, outcome is usually recovery with fibrous deformation and post-TB pyelonephritis. With inappropriate therapy KTB-2 may progress to the next stage. Mtb is not detected in all cases and may be resistant.

KTB-3 has two routes of pathogenesis: from TB of parenchyma or from papillitis. The first means the development of a subcortical cavern without connection to the collecting system. The clinical manifestation of a subcortical cavern is like a renal carbuncle, thus the diagnosis usually is made after the operation. The second is the progress of the destruction of the papilla until cavern development. Cavernous KTB may be unilateral and bilateral, papillitis in one kidney and cavernous TB in another is usual; in this case the patient should be treated as a patient with KTB-3. Complications develop in more than half of the patients. Full recovery by anti-TB drugs is impossible, surgery is in general indicated. The benefit outcome is the formation of a sterile cyst; negative outcome is progress destruction until polycavernous TB.

KTB-4 means several caverns in the kidney, nevertheless overall renal function may be sufficient. KTB-4 may result in fistula due to pyonephrosis. Self-recovery is also possible; when stricture of the ureter locks the kidney and caseation in the caverns is impregnated by calcium, so-called auto-amputation of the kidney occurs. KTB-4 is almost always complicated; very often the contralateral kidney is involved. Recovery by medication is impossible, nephroureterectomy is indicated.

TB of the ureter usually develops in the lower third, but multiple lesions are also possible. Incorrect therapy may lead to the development of the ureteral stricture that may result in the loss of kidney, even if TB is finally cured.

Bladder TB is divided into four stages [Kulchavenya, 2014]:

stage 1, tubercle infiltrative;

stage 2, erosive ulcerous;

stage 3, spastic cystitis (bladder contraction, false microcystitis), in fact overactive bladder;

stage 4, real microcystitis up to full obliteration.

The first two stages should be treated by standard anti-TB drugs, the third stage with standard anti-TB drugs and trospium chloride, and the fourth stage is indicated for cystectomy with following enteroplasty.

There is one more form of bladder TB, iatrogenic BCG-induced bladder TB, which develops as a complication of BCG therapy for bladder cancer.

TB of the urethra

TB of the urethra is nowadays not a frequent complication; usually it is diagnosed at the stage of a stricture.

Prostate TB

Prostate TB is an often under-diagnosed disease. Three quarters of men that died from all forms of TB had prostate TB that was mostly overlooked while they were alive [Kamyshan, 2003]. Prostate TB is important as: (1) it may be as a sexually transmitted disease, as up to 50% of prostate TB patients have Mtb in ejaculate if they were comorbid with hepatitis and syphilis [Aphonin et al. 2006]; (2) it leads to infertility; (3) it results, like any prostatitis, in chronic pelvic pain that significantly reduces quality of life; (4) it decreases the sexual function, also reducing quality of life [Kulchavenya et al. 2012]. In 79% prostate TB was accompanied by KTB, in 31% by TB orchiepididymitis, and in 5% isolated prostate TB was diagnosed [Kulchavenya, 2014].

TB orchiepididymitis/epididymitis

TB of the testis is always secondary to infection of the epididymis, which in most cases is blood-bourne because of the extensive blood supply of the epididymis, particularly the lobus minor. In 62% of patients with orchiepididymitis KTB is diagnosed as well. Every third patient has bilateral lesions. Isolated TB epididymitis was revealed in 22% as an accidental surgical finding. In about 12% the disease is complicated by fistula [Kulchavenya, 2014; Kulchavenya et al. 2012].

TB of the penis

Penile TB is very rare but can occur after sexual coitus with infected females [Narayana et al. 1976] or via a direct infection through a penile wound during ritual circumcision. Penile lesions present as ulcers on the glans or penile skin. Currently it is basically a complication of BCG-therapy [Sharma et al. 2011].

High-risk factors for UGTB

UGTB has several risk factors, including:

contact with TB infection;

TB localization, active or cured, especially disseminated forms;

urinary tract infection (UTI) with frequent recurrence, resistant to standard therapy;

UTI with persistent dysuria, leading to decreasing bladder volume;

sterile pyuria;

pyuria in all portions of 3-glass test in patients with epididymitis/orchiepididymitis;

pyospermia and/or hemospermia;

scrotal, perineal and lumbar fistula.

Clinical features

Clinical features of UGTB have no specific signs, are unstable and depend on many factors; this is one of the reasons for late diagnosis.

KTB patients complaint of flank pain (up to 80%) and/or dysuria (up to 54%). If the urinary tract is involved, renal colic (24%) and gross hematuria (up to 20%) are possible. Prostate TB manifests by perineal pain and dysuria, and in half of the cases by hemospermia. TB orchiepididymitis always starts from epididymitis, isolated TB orchitis is not possible. Edema and swelling of the scrotal organs and pain are most often the first symptoms, in 68% there is an acute debut of the disease. Nevertheless, in 32–40% the disease has a chronic or asymptomatic course [Figueiredo and Lucon, 2008; Kulchavenya, 2014; Miyake and Fujisawa, 2011; Carrillo-Esper et al. 2010].

Diagnostics

History (anamnesis)

Risk factors for UGTB should be evaluated carefully.

Physical examination

Special attention should be paid to any fistula. In an acute course of TB epididymitis, hard painful enlarged epididymis intimate welded with testis is palpated. In a chronic course, epididymis is hard, enlarged, and painless with clear border from the testis; in 35–40% the lesion is bilateral. Digital rectal examination of the patient with prostate TB shows moderate enlarged tuberous prostate gland with weak pain. Again, scrotal and perineal fistulae are highly suspicious for TB [Bennani et al. 1995].

Laboratory findings

Urinalysis

Leukocyturia is found in 90–100% of patients with KTB, and hematuria in 50–60%.

Bacteriology

In the ‘before-antibacterial era’, sterile pyuria was specific for KTB, but now up to 75% patients have nonspecific pyelonephritis alongside KTB and so microflora and Mtb may be found in urine together [Chiang et al. 2010; Hoang et al. 2010; Lenk, 2011]. Absolutely proven and evident diagnosis UGTB is when Mtb is revealed, but in recent years Mtb may be found in only about half of TB patients.

To diagnose UTI a growth of microflora of not less than 103 CFU/ml is needed, but even one single Mtb cell evidentiary confirm UGTB [Kulchavenya, 2014; Kulchavenya et al. 2014].

Histological investigation

Histological investigation may reveal epithelioid granuloma, caseous necrosis, but this is rapidly replaced with fibrous tissue. If the patient was treated with fluoroquinolones and amikacin for UTI, which in fact masks UGTB, specific histological changes transform in fibrosis, and pathomorphological confirmation of the disease becomes impossible.

X-ray and ultrasound investigations

Ultrasound investigation may give indirect evidence of UGTB only. As prostate TB in 79% is accompanied by KTB, pathological changes detected by renal ultrasound in patients with ‘chronic prostatitis’ are very suspicious for UGTB. TB epididymitis and orchitis present as diffusely enlarged lesions, which may be homogeneous or heterogeneous and can also present as nodular enlarged heterogeneously hypoechoic lesions [Turkvatan et al. 2004].

Transrectal ultrasound investigation may reveal hypoechoic and hyperechoic lesions of the prostate, predominately in the peripheral zone; as well as a prostatolithiasis which in fact may be calcified zones of TB inflammation [Scherban and Kulchavenya, 2008].

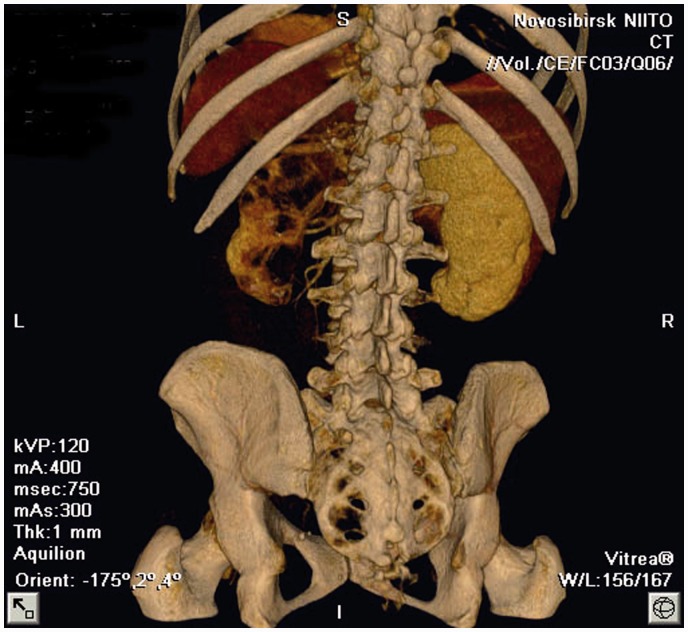

Complex radiography is indicated for patients suspected for UGTB: plain X-ray films of the urinary tract may detect calcification in the renal areas and in the lower urogenital tract; IVU is indicated for patients with leukocyturia and/or abnormality on ultrasound investigations. A typical X-ray picture of KTB-4 is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Slice computer tomogram: kidney tuberculosis stage 4.

Retrograde urethrography should be performed in all patients with genital TB to exclude caverns of the prostate. X-ray examination is highly informative in cavernous forms of UGTB: both kidney (IVU) and prostate TB (urethrography), but multisliced computer tomography is significantly more informative. In contrast-enhanced CT scan, TB of the prostate or seminal vesicles can be seen as low-density or cavitation lesions due to necrosis and caseation with or without calcification. Without calcification, the findings may be similar to pyogenic prostatic abscess [Wang et al. 1997a, 1997b]. However, in the early stages UGTB has no specific radiological features.

Instrumental procedures

Instrumental procedures for UGTB diagnosis have limited value, especially nowadays.

Cystoscopy is indicated for all UGTB patients having dysuria. Persistent dysuria in KTB patient is the basis for diagnosis of bladder TB, even without histological confirmation, which may be obtained in 12% of the patients with bladder TB stage 4 only [Kholtobin and Kulchavenya, 2013]. Any mucosal changes should be biopsied and investigated both by histology and bacteriology, although absence of the specific findings does not exclude diagnosis of TB by the reasons mentioned above.

Ureteropyeloscopy may accidentally reveal TB ulcers, typically when the procedure is performed on a patient with renal colic and roentgen-negative stone, misdiagnosed as urolithiasis. Urethroscopy is not informative.

Prostate biopsy should be made only after urethrography for excluding caverns. Tissue of the gland should be investigated by histology and bacteriology, at least by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [Hemal et al. 2000; Singh et al. 2011].

Scrotal organs biopsy, Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) may be useful in the diagnosis of TB of external male genitals [Suárez-Grau et al. 2012]. However, scrotal violation should be considered if the mass is malignant, as there were fatal complications after biopsies were performed on nontreated patients with active UGTB due to fulminant generalization of TB.

Provocative tests

The Mantoux test is positive in more than 90% of TB patients, but it has no value in regions with a severe epidemic situation (e.g. China, Russia, India, Africa), where almost all adults are infected with Mtb and thus all have positive skin tuberculin test. The new Diaskintest has high specificity, but low sensitivity, and is not recommended for the diagnosis of UGTB. Subcutaneous tuberculin provocative test is recommended [Kulchavenya, 2014].

Therapy ex juvantibus

Therapy ex juvantibus may be of the first type, when the patient takes antibiotics which do not inhibit Mtb (fosfomycin, cefalosporins, and nitrofurantoin), and of the second type, when the patient takes two to four antibiotics which inhibit only Mtb (isoniazid, PAS, protionamid, etionamid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamid). Patients with low-grade suspicion for UGTB should be treated with therapy ex juvantibus of the first type, a positive result allows us to exclude the diagnosis UGTB. If there remains doubt about the etiology of UTI, therapy ex juvantibus of the second type is indicated.

If there is no evidence of Mtb, a diagnosis of UGTB may be made on the basis of skin test, histological picture, caverns revealed by urography, sterile pyuria, etc. [Kulchavenya, 2014].

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in preparing this article.

References

- Aphonin A., Perezmanas E., Toporkova E., Khodakovsky E. (2006) Tuberculous infection as sexually transmitted infection. Vestnik poslediplomnogo obrazovaniya 3–4: 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Bennani S., Hafiani M., Debbagh A., el Mrini M., Benjelloun S. (1995) Urogenital tuberculosis. Diagnostic aspects. J Urol 101: 187–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo-Esper R., Moreno-Castañeda L., Hernández-Cruz A., Aguilar-Zapata D. (2010) A renal tuberculosis. Cir Cir 78: 442–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang L., Jacobsen A., Ong C., Huang W. (2010) Persistent sterile pyuria in children? Don't forget tuberculosis!. Singapore Med J 51(3): 48–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo A., Lucon A. (2008) Urogenital tuberculosis: update and review of 8961 cases from the world literature. Rev Urol 10: 207–217. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemal A., Gupta N., Rajeev T., Kumar R., Dar L., Seth P. (2000) Polymerase chain reaction in clinically suspected genitourinary tuberculosis: comparison with intravenous urography, bladder biopsy, and urine acid fast bacilli culture. Urology 56: 570–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang N., Nhan L., Chuyen V. (2009) Genitourinary tuberculosis: diagnosis and treatment. Urology 4A(Suppl.): S241. [Google Scholar]

- Kamyshan, I. (2003) Guideline on urogenital tuberculosis. Kuev, pp. 363–424.

- Kholtobin D., Kulchavenya E. (2013) Surgery for bladder tuberculosis, Berlin: Palmarium Academium Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kulchavenya E. (2014) Urogenital Tuberculosis: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Therapy, New York: Springer; DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-04837-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kulchavenya E., Brizhatyuk E., Baranchukova A., Cherednichenko A., Klimova I. (2014) Diagnostic algorithm for prostate tuberculosis. Tuberculez I bolezn legkih 5: 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kulchavenya E., Kim C., Bulanova O., Zhukova I. (2012) Male genital tuberculosis: epidemiology and diagnostic. World J Urol 30: 15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenk S. (2011) Genitourinary tuberculosis in Germany: diagnosis and treatment. Urologe 50: 1619–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake H., Fujisawa M. (2011) Tuberculosis in urogenital organs. Nihon Rinsho 69: 1417–1421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayana A., Kelly D., Duff F. (1976) Tuberculosis of the penis. Br J Urol 48: 274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter M., III (1894) Uro-genital tuberculosis in the male. Ann Surg 20: 396–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherban M., Kulchavenya E. (2008) Prostate tuberculosis – new sexually transmitted disease. Eur J Sexol Sexual Health 17(Suppl. 1): S163. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V.K., Sethy P.K., Dogra P.N., Singh U., Das P. (2011) Primary tuberculosis of glans penis after intravesical Bacillus Calmette Guerin. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 77: 47–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V., Sinha R., Sankhwar S., Sinha S. (2011) Reconstructive surgery for tuberculous contracted bladder: experience of a center in northern India. Int Urol Nephrol 43: 423–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Grau J., Bellido-Luque J., Pastrana-Mejía A., Gómez-Menchero J., García-Moreno J., Durán-Ferreras I., et al. (2012) Laparoscopic surgery of an enterovesical fistula of tuberculous origin (terminal ileum and sigmoid colon). Rev Esp Enferm Dig 104: 391–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkvatan A., Kelahmet E., Yazgan C., Olcer T. (2004) Sonographic findings in tuberculous epididymo-orchitis. J Clin Ultrasound 32: 302–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Sheu M., Lee R. (1997a) Tuberculosis of the prostate: MR appearance. J Comput Assist Tomogr 21: 639–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Wong Y., Chen C., Lim K. (1997b) CT features of genitourinary tuberculosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr 21: 254–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildbolz H. (1937) Ueber urogenical tuberkulose. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 67: 1125. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2014) WHO Fact sheet N°104, Reviewed March 2014, available at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/.